The Connection Between Social Security Disability Benefits and Health Coverage Through Medicaid and Medicare

This brief was updated on October 24, 2024 to incorporate updates to Medicare and Medicaid administrative data.

In 2021, 13 million people under age 65 received income from the Social Security disability programs, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI), which provide monthly income to people who are unable to work on account of a disability. A less-commonly appreciated benefit of qualifying for Social Security disability programs is the connection to health insurance coverage through Medicare or Medicaid. In most states, SSI beneficiaries automatically qualify for and receive Medicaid coverage, while SSDI beneficiaries qualify for Medicare after receiving disability benefits for at least two years. Many who receive benefits from the SSDI and SSI programs also qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid, known as dual-eligible individuals.

This analysis examines enrollment in disability programs and characteristics of enrollees from 2002-2022 Social Security Administration data and related health coverage through the Medicare and Medicaid programs using data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for 2021, the most recent year of data available. (See methods for details.) State-level data about the disability programs are also available on KFF’s State Health Facts.

Key Takeaways

- In 2021, 12.9 million people were eligible for Medicare or Medicaid because they received disability benefits from either SSDI or SSI. Of that total, 4.6 million, or more than one-third (35%), qualified for health coverage under both Medicare and Medicaid (dual-eligible individuals). Another 4.8 million SSI beneficiaries had Medicaid coverage only and 3.5 million SSDI beneficiaries had Medicare coverage only.

- A total of 13.0 million people under age 65, including working-age adults and children, received disability benefits in 2022, including 7.8 million people who received income from SSDI, 4.2 million who received income from SSI, and 1 million who received income from both programs.

- Enrollment of working-age adults in both the SSDI and SSI programs has decreased since 2014, reflecting the changing demographics of the U.S. population, the economy, and other factors that have reduced the number of new beneficiaries, including in more recent years, the lasting effects of Social Security office closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. The decline in SSDI enrollment has also meant a decline in the number of Medicare beneficiaries under age 65 who qualify due to disability.

- Mental disorders—which include intellectual and developmental disorders and other mental disorders—comprise the largest percentage of disabling conditions across both programs. In the SSDI program, musculoskeletal conditions are the most common disabling conditions among disabled beneficiaries (30%), followed by other mental disorders (16%) and intellectual/developmental disorders (14%). For SSI beneficiaries, intellectual and developmental disorders are the most common disabling conditions (33%), followed by other mental disorders (19%) and musculoskeletal disorders (12%).

- The average monthly benefit in 2022 was more than twice as large for disabled workers in the SSDI program (nearly $1,500 per month) than disabled beneficiaries in the SSI program (nearly $650 per month).

How many people under age 65 qualify for Medicaid and Medicare through the Social Security disability programs?

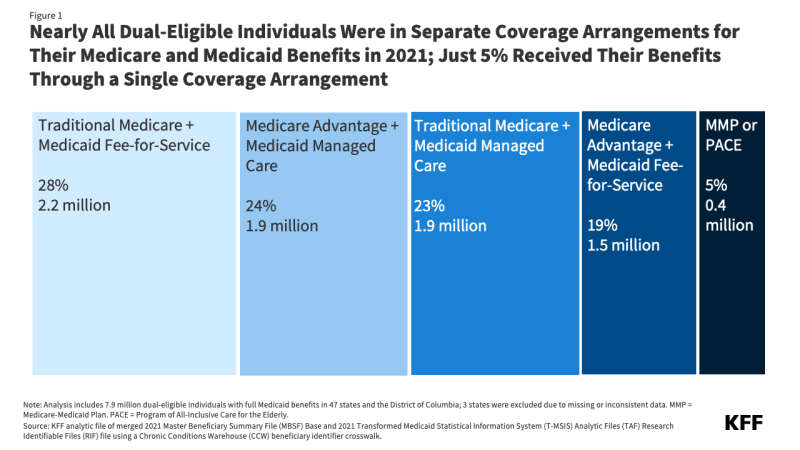

In 2021, 12.9 million people who received benefits through the Social Security disability programs qualified to receive coverage from Medicare, Medicaid, or both programs on account of their eligibility for disability benefits (Figure 1). While 61% of working age adults and nearly half of children had health coverage through an employer in 2022, employment-based coverage is much less common among people with disabilities, who are less likely to work. As a result, the Social Security disability programs – Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) (see Box 1) – play an important role in helping people with disabilities access health insurance coverage through the Medicaid or Medicare programs, with some people with disabilities qualifying for health coverage under both Medicare and Medicaid (known as dual-eligible individuals).

Of the 12.9 million people with disabilities who have coverage from Medicare, Medicaid, or both based on their eligibility for disability programs, a total of 4.6 million, or more than one-third (35%), are dual-eligible individuals. Overall, the overall group includes:

- 4.8 million SSI beneficiaries who have Medicaid only;

- 3.5 million SSDI beneficiaries who have Medicare only;

- 3.0 million SSDI beneficiaries who have both Medicare and Medicaid; and

- 1.6 million beneficiaries receiving both SSDI and SSI, who have both Medicare (through SSDI) and Medicaid (through SSI).

Although most people qualify for Medicare based on age when they turn 65, people under age 65 may become eligible for Medicare if they have received SSDI payments for 24 months. In 2021, 8.3 million people under the age of 65 were eligible for Medicare because of a disabling condition. Nearly all (8.1 million) were eligible through SSDI, and 0.2 million were eligible because they had End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) but did not receive SSDI. SSDI beneficiaries often must wait 5 months for SSDI payments after the onset of benefits, followed by a two-year waiting period between receipt of SSDI benefits and Medicare eligibility, referred to as the “Medicare waiting period.” It is unknown how many people are currently in the waiting period or what their health insurance coverage is during this period. Because of the length of the SSDI application process and the fact that SSDI eligibility is retroactive, applicants may complete some or all of the waiting period prior to receiving SSDI benefits, but many experience gaps in coverage during this time too. (Those under age 65 who qualify for Medicare based on having ESRD or Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) do not have to wait 24 months for their Medicare benefits to start because they are not required to qualify for SSDI first.)

According to KFF analysis, although majorities of people with Medicare of all ages rate Medicare positively, people under age 65 with disabilities are less likely than older beneficiaries to give positive ratings to Medicare and some features of it, such as the quality and availability of providers. Medicare beneficiaries under age 65 with disabilities have also reported worse access to care, more cost concerns, and lower satisfaction with care than those age 65 or older. The lower ratings by people under 65 with disabilities may possibly be related to their different pathways to Medicare eligibility and because the program was originally designed to cover older adults, with coverage for younger people with disabilities added later. Also, because a larger share of people with Medicare under 65 with disabilities report that they are in fair or poor physical and mental health and have severe chronic conditions compared to people age 65 or older, those under 65 with disabilities may be more likely to have multiple encounters with the health care system during the year and encounter problems when they do.

States must generally provide Medicaid to people who receive SSI. In 2021, 6.5 million people were eligible for Medicaid through the SSI disability program. If states do not want to use the SSI eligibility criteria, they can use more restrictive rules so long as the rules are no more restrictive than what the state had in place in 1972 when the SSI program was established. There are currently 8 states using their own criteria, known as the 209(b) states: Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, North Dakota, and Virginia.

Box 1: What are the Differences Between SSDI and SSI?

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) are federal programs administered by the Social Security Administration (SSA), but they differ in terms of how people qualify, the benefits they receive, and how they are financed. Both programs require adults under age 65 to have a qualifying disability, but SSI also includes qualifying disability criteria for children.

How do people qualify for SSDI and SSI? To qualify for SSDI, enrollees must have a sufficient work history, which varies by age but generally requires ten years of employment at least five of which were within the past decade. Some individuals with a disability can qualify based on a relative’s work history including:

- Spouses of disabled workers (and divorced spouses if the marriage lasted for at least 10 years) if they have a child in their care or if they are at least 63 years old; and

- Children of disabled workers if they are under age 18, 18 years old but still in high school, or are adults who have disabilities that started under the age of 22.

SSI is a means-tested program in which eligibility is based on an assessment of income and resources. To qualify, SSI enrollees must have low incomes, limited assets, and either be over age 64 or have a qualifying disability. Unlike SSDI, SSI is available to people regardless of their work history. The SSA redetermines eligibility and benefit amounts for SSI beneficiaries every 1 to 6 years or when a change that affects eligibility or payment is reported.

What benefits do people receive and how are the programs financed? Under both programs, the federal government pays monthly benefits to people who meet the eligibility criteria, and 45 states add supplemental payments for some SSI recipients. Maximum monthly benefits for SSI are legislatively established and updated annually to reflect inflation. Monthly benefits for SSDI reflect the payments workers made into the program through payroll taxes and are updated annually based on the growth in average wages. There are no state supplemental payments for SSDI. People can receive both SSDI and SSI if the income from SSDI is less than the maximum SSI payment. In those cases, SSI can cover the difference between the SSDI income amount and the maximum SSI.

How many people under age 65 receive income from Social Security disability programs?

Among the 268 million people under age 65 in the U.S., 5% or 13 million people received income from SSDI, SSI, or both programs in 2022. More than half (60%, or 8 million) of Social Security disability program beneficiaries under 65 exclusively receive SSDI income, and nearly a third (32%, or 4 million) receive only SSI, while over 1 million people received benefits from both programs (Figure 2).

How has enrollment in the Social Security disability programs changed over time?

Enrollment of working-age adults in the Social Security disability programs increased from the early 2000s through 2014 but has been declining since (Figure 3). Enrollment of people under age 65 in SSDI and SSI has decreased from 14.9 million beneficiaries in 2014 to 13.0 million beneficiaries in 2022. Enrollment trends in the disability programs reflect the demographics of the U.S. population, the economy, and other factors. Program size depends in part on the size of the labor force, and some of the decreased participation in recent years reflects the baby boomers entering their retirement years. For the SSDI program, participation also requires people to meet past employment requirements and lower labor force participation means fewer people can meet those requirements. Research has also found lower application and award rates for “contingent workers,” which includes independent contractors, consultants, and those in temporary, on-call, and gig economy jobs, who make up an increasing share of the workforce. Lower SSDI enrollment over the past decade also likely reflects fewer applications stemming from the end of routinely-mailed social security statements in 2011.

More stringent disability determinations could also contribute to the lower enrollment. Between 1999 and 2019, the percentage of applicants who were approved to receive benefits (the “award rate”) declined for both disability programs: from 56% to 29% for SSDI and from 44% to 34% in 2021 for SSI. Lower award rates mean that even if a similar number of people apply, fewer people will enroll and receive benefits.

The decline in SSDI enrollment has meant fewer people under age 65 qualifying for Medicare due to having a long-term disability. The total number of Medicare beneficiaries under age 65 with disabilities (excluding those who qualify based on having end-stage renal disease) has declined since 2016, both in terms of the total number and the share of overall Medicare enrollment, based on Medicare enrollment data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. In 2016, there were 8.6 million Medicare beneficiaries under age 65, or 16% of all beneficiaries, decreasing to 7.2 million in 2023, or 11% of the total.

The same trend is not observed in Medicaid because people have more options for qualifying for Medicaid than they do Medicare. Between 2014 and 2022, most states adopted Medicaid expansions under the Affordable Care Act, which provided another mechanism for adults under age 65 to qualify for Medicaid and spurred enrollment growth. Enrollment also grew between 2020 and 2023 because of the COVID-19 continuous enrollment period, a three-year period during which Medicaid eligibility disenrollments were paused.

Historically, economic downturns led to increases in SSDI and SSI enrollment, but notably, there was no enrollment surge during the economic downturn associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, the enrollment decline accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, when Social Security offices were closed for 2 years, likely further reducing the number of applicants. Office closures also contributed to a backlog of cases that is causing people to wait longer for eligibility decisions: Social Security data show that the average review time for initial applications increased from 4 months or less before the pandemic to nearly 8 months in 2023. Similar trends occurred for applications that were reconsidered after an initial denial.

The application for Social Security disability benefits can be a lengthy and complicated process, spanning months, if not years. A chart visualizing the steps to disability determinations in 2022 by the National Organization of Social Security Claimants’ Representatives shows that 62% of the 1.8 million applicants in 2022 were denied at the initial application, but that hundreds of thousands pursued reconsiderations and subsequent legal proceedings to establish eligibility. A 2022 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that legal representation did not affect the likelihood of a successful SSDI outcome but reduced the time it took for approval by nearly one year. The challenge with demonstrating eligibility is in proving that one has a disabling condition that makes substantive employment impossible.

The Biden-Harris Administration’s proposed FY 2025 budget includes a $1.3 billion (9%) increase to the Social Security Administration’s budget from FY 2023 to 2025 to improve customer service across field offices, disability determination, and teleservice, and reduce wait times. The Biden-Harris Administration also supports using the budget increase to advance equity and accessibility. The new funding would support simplifying the SSI application process, broadening access to Social Security programs especially for unserved populations, and preventing overpayments. The Social Security Administration would also use the funding to continue improving information technology systems to make accessing services and communication with staff easier both online and via phone.

What are the most common conditions that qualify people for Social Security disability benefits?

For both SSDI and SSI, musculoskeletal system diseases and mental disorders are the most common conditions that qualify people for disability benefits (Figure 4). Both Social Security disability programs use a strict definition of disability when assessing eligibility, which limits how many people with disabilities ultimately qualify for SSDI or SSI payments. The Social Security Administration defines disability for adults as the inability to engage in any “substantial gainful activity” because of one or more medically determinable physical or mental disabilities that are either expected to result in death or have lasted or are expected to last for a continuous period of at least 12 months. Substantial gainful activity describes a level of work that involves doing significant physical or mental activities or a combination of both. For children to qualify as disabled, they must be under 18 and have one or more physical or mental impairments which result in marked and severe functional limitations and the impairment must have lasted or be expected to last for at least 12 months or be expected to result in death.

Over the past two decades, musculoskeletal system diseases and mental disorders (including both intellectual and developmental disorders and other mental disorders) have accounted for the largest shares of disability determinations, and in 2022, these conditions combined account for 60% of disability determinations among SSDI beneficiaries and 64% among SSI beneficiaries. The most common conditions for SSDI beneficiaries are musculoskeletal system diseases, which include non-healing or complex fractures, abnormalities of major joints, and disorders of the spine. The most common conditions for SSI beneficiaries are intellectual/developmental disorders which include autism spectrum disorders and neurocognitive disorders. Other mental disorders include depressive, bipolar, and related conditions and schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders.

How much do Social Security disability program beneficiaries receive in monthly benefits?

SSDI beneficiaries receive average monthly benefits that are over twice as large as what SSI beneficiaries receive, with monthly SSDI payments for disabled workers averaging nearly $1,500 per month, compared with roughly $650 per month for people receiving SSI benefits (Figure 5). Family members of SSDI workers receive lower monthly benefits, on average: just under $900 for widowers and $1,000 for adult children. The monthly payment from SSDI is calculated using a statutory formula that accounts for people’s earnings and is designed to pay higher benefits to people with higher earnings but to replace a larger percentage of earnings for people with lower earnings. In 2022, SSDI benefits ranged from less than $600 to more than $3,000 each month. The maximum SSI benefit is set by Congress and in 2022 was $841 per month for an individual ($943 in 2024) and $1,261 for a couple ($1,415 in 2024). If people have non-SSI income, their SSI benefits are reduced by the amount of countable income.

Many beneficiaries are now facing benefit reductions on account of prior overpayments by the Social Security Administration, as reported by KFF Health News, but the Biden-Harris Administration is taking steps to limit the effects of benefit reductions. Each year, more than 2 million beneficiaries have been receiving notices that their disability benefits were overpaid and are being asked to repay the specific amounts within 30 days or have their monthly disability benefits reduced. In many cases, those payments had been made years earlier without the recipients’ knowledge. There have been overpayments in both programs, but they are more common in SSI because SSI eligibility and payment amounts change when recipients experience changes in income and assets.

From April through June 2024, new overpayment policies went into effect to address those benefit reductions, including:

- Limiting the amount that can be withheld from a recipient’s monthly disability benefits (to adjust for overpayments) to no more than 10% of the recipient’s monthly benefits for SSI recipients and either 10% or $10 for SSDI recipients (whichever is greater), rather than withholding the entire amount,

- Increasing the amount of time for recipients to repay the overpayment,

- Making overpayment notices easier to understand,

- Simplifying the waiver application for beneficiaries who meet repayment exemption criteria, and

- Holding the Social Security Administration responsible for providing proof of overpayment rather than the beneficiary.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Methods

Included Areas: The analysis includes data from the 50 states and Washington D.C. (excluding enrollees in the territories and foreign countries).

Included Beneficiaries: Beneficiaries of Social Security disability programs who are under age 65.

Disability Programs: Data on the Social Security disability programs come from the Annual Statistical Report on the Social Security Disability Insurance Program, 2002-2022; and the Supplemental Security Income Annual Statistical Report, 2002-2022. The numbers in the issue brief come from the online appendix tables.

Medicare and Medicaid Enrollment: Data are from a KFF analytic file that merged the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse 2021 research-identifiable Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF) Base and the 2021 Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS) Analytic Files (TAF) Research Identifiable Files (RIF) file using a Chronic Conditions Warehouse (CCW) beneficiary identifier crosswalk. The numbers include all Medicare enrollees who were currently eligible for Medicare on the basis of disability using ENTLMT_RSN_ORIG with values of 1, 3 and under 65 using AGE_AT_END_REF_YR in 2021, and all Medicaid enrollees who were currently eligible for Medicaid on the basis of SSI enrollment using the monthly ELGBLTY_GRP_CD with values of 11-22, 37, 38, 40, 41 and under 65 using AGE in 2021. People with records in both the Medicare and Medicaid data were categorized as dual-eligible beneficiaries.

Limitations: The estimates for SSDI and SSI enrollment are not comparable to the estimates of SSI and SSDI enrollees with Medicare and Medicaid coverage in 2021 for several reasons:

- The data come from different sources and years.

- The SSDI and SSI numbers are in the month of December whereas the Medicare and Medicaid numbers are people who were ever enrolled during the year.

- Some people who are eligible for Medicare or Medicaid in a given month because of SSDI or SSI may not be receiving benefits from those programs in that month, particularly, if they are enrolled in certain programs designed to help people with disabilities work. This may be especially true between the years of 2020 and 2023 because states did not disenroll people during that time period on account of a continuous enrollment provision.

- Some people who are receiving SSDI or SSI in a given month may not be receiving Medicare or Medicaid. This occurs most frequently for people with SSDI who must receive two years of SSDI benefits before they become eligible for Medicare.

Irving Washington

Irving Washington  Hagere Yilma

Hagere Yilma