Medicaid Coverage for Women

Medicaid, the nation’s health coverage program for poor and low-income people, provides millions of low-income women across the nation with health and long-term care coverage. Women comprise the majority of the adult Medicaid population and the program offers coverage of a wide range of primary, preventive, specialty, and long-term care services that are important to women across their lifespans. Given the importance of the program for low-income women and their families, changes to the program, such as Medicaid expansion and the new state option to extend postpartum coverage beyond 60 days, have significant implications for low-income women’s access to coverage and care. Proposed congressional legislation would have further implications for Medicaid and women from postpartum coverage to maternal health, as well the Medicaid coverage gap and would include investments in health and community-based services. This data note presents key data points describing the current state of the Medicaid program as it affects women.

Who is Eligible for Coverage?

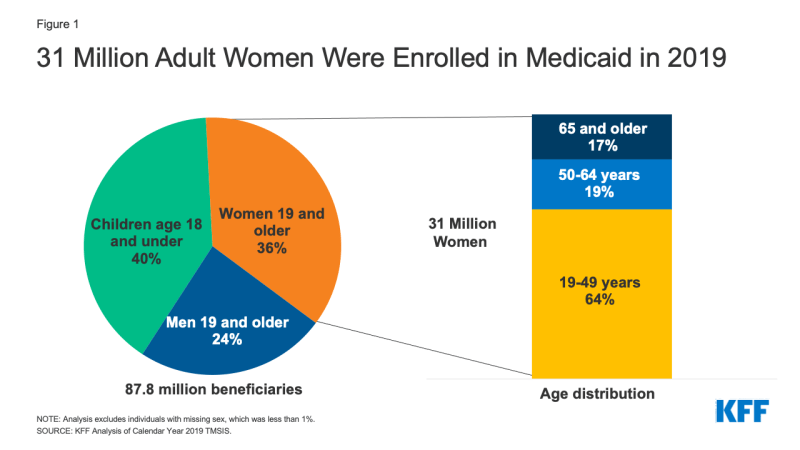

In 2019 adult women comprised 36% of the overall Medicaid population and the majority of adults on the program (Figure 1). Prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), women were more likely to qualify for Medicaid than men because of their lower incomes and because they were more likely to belong to one of Medicaid’s categories of eligibility for adults: pregnant, parent of a dependent child, senior, or person with a disability. The 2010 ACA added a new Medicaid eligibility category by extending Medicaid eligibility to nearly all non-elderly individuals with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL).1

- As of December 2021, 38 states and DC have opted to expand eligibility for Medicaid under the ACA, which allows nonelderly low-income women with incomes below 138% FPL to qualify regardless of their pregnancy, parenting or disability status.

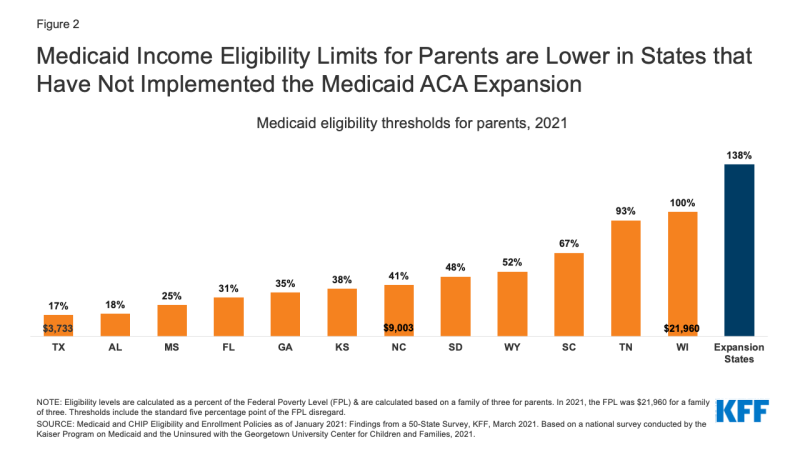

- In the 12 states that have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA as of January 2022, adults only qualify if they meet income criteria AND belong to one of the previously mentioned eligibility categorical groups. While there are federal eligibility minimums, states have the option to expand eligibility levels for each group up to certain limits. As a result, income eligibility criteria vary for different groups of beneficiaries within as well as between states. Eligibility levels are much lower for parents in the states that have not expanded Medicaid compared to those that have, ranging from 17% FPL in Texas, to 100% FPL in Wisconsin (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Parents are Lower in States that Have Not Implemented the Medicaid ACA Expansion

- Many women who are uninsured are potentially eligible for coverage but are not enrolled. In 2020, one in five (2.1 million) uninsured women were eligible for Medicaid but were not enrolled, and one million women were in the “Medicaid coverage gap.” They live in a state that has not expanded its Medicaid program and do not qualify for Medicaid but have incomes below the lower level (100% FPL) for Marketplace subsidies.

Profile of Nonelderly Women Covered by Medicaid

The diverse population of women covered by Medicaid face many social, economic, and health challenges that affect their ability to receive timely and high-quality health care.

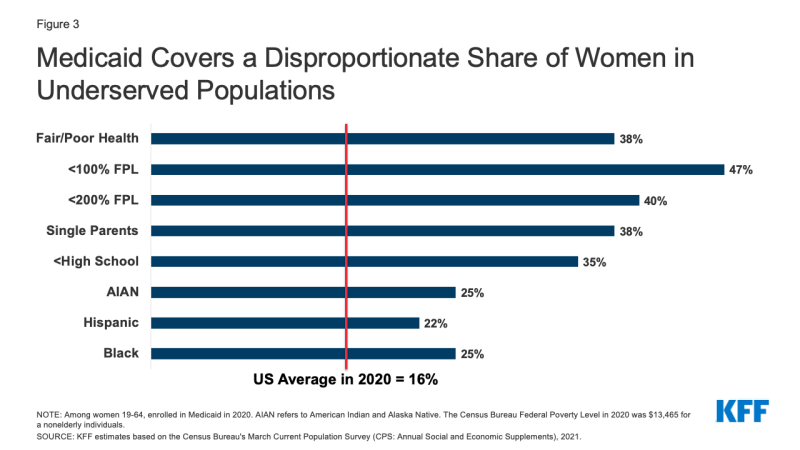

- In 2020, Medicaid covered 16% of nonelderly adult women in the United States, but coverage rates were higher among certain groups, such as those in fair or poor health, women of color, single mothers, low-income women, and women who have not completed a high school education (Figure 3).

- Over half of nonelderly women on Medicaid who do not receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and who are not dually eligible for Medicare work outside the home (59%). Many others are not employed for pay but are caring for family members (19%), are not working due to illness or disability (9%) or attend school (6%). Approximately six in ten mothers on Medicaid (62%) are working and another quarter are caring for family members. Among women without children, half (56%) are working and another 14% are not working due to illness or disability (Figure 4).

- Differences in Medicaid eligibility levels and poverty rates across the states translate into vastly different Medicaid coverage rates for women across states, from a low of 7% in South Dakota to 29% in New Mexico (Figure 5).

Reproductive Health

Roughly two-thirds (64%) of adult women with Medicaid coverage are in their reproductive years (19 to 49).2 Medicaid covers a wide range of reproductive health care services, including family planning, and pregnancy-related care including prenatal services, childbirth, and postpartum care—all without cost-sharing. Medicaid coverage of abortion services, however, is very limited under federal law and in most states.

Family planning

Federal law requires state Medicaid programs to offer family planning benefits, but states determine the specific services and supplies for those who qualify through pre-ACA pathways. For the ACA expansion populations, the ACA requires states to cover all FDA approved, granted, and cleared contraceptive methods, counseling on STIs and HIV, and screening for breast and cervical cancers. Research has found that most states have aligned their benefits and cover these services across all eligibility groups.

- The federal government pays 90% of costs for family planning services, a higher federal matching rate than for other services (typically between 50% and 78%)3. Women covered by Medicaid cannot be charged any out-of-pocket costs for family planning services.

- The federal government also guarantees Medicaid beneficiaries “free choice of provider,” which allows them to seek care from any qualified participating provider that offers the services. While free choice of provider is not specific to family planning, it means that states cannot bar providers from the Medicaid program simply because they provide abortion services. However, judicial rulings have allowed some states to exclude Planned Parenthood from their Medicaid programs. These cases are ongoing. For beneficiaries enrolled in managed care arrangements, there is a protection that specifically allows them to seek family planning services from the provider of their choice even if the provider is outside of the plan’s network.

- Twenty-eight states currently operate limited scope Medicaid family planning programs which extend access to family planning services to uninsured women who do not qualify for full Medicaid coverage because their incomes exceed the Medicaid income thresholds or they have lost Medicaid eligibility after having a baby and do not have a pathway stay on the program after the 60 day postpartum coverage period.

Maternity Care

Medicaid is the largest single payer of pregnancy-related services, financing 42% of all U.S. births in 2019. In six states Medicaid covers more than 60% of all births. By federal law, all states provide Medicaid coverage without cost sharing for pregnancy-related services to pregnant women with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) and cover them up to 60 days postpartum. States now have the option to extend postpartum coverage beyond 60 days—as of January 2022, 25 states have taken steps to extend postpartum coverage.

- Similar to family planning, there is no federal definition of what services states must cover under their traditional Medicaid programs for pregnant women beyond inpatient and outpatient hospital care, but states that have expanded Medicaid eligibility must cover all preventive services recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) to individuals who qualify through this pathway, which includes a broad range of preventive services for pregnant women. States may not charge cost-sharing for any pregnancy-related services. Overall, most states cover a broad range of maternity care services, including prenatal screenings, folic acid supplements, and breastfeeding supports.

- In the 12 states that have not expanded Medicaid coverage under the ACA, many women lose their Medicaid eligibly 60 days post-partum because they no longer qualify for coverage, even though their infants are Medicaid eligible for their first year. This is because the income eligibility for pregnancy-related care is typically considerably higher than those offered to parents of dependent children. In the states that have expanded Medicaid eligibility, most women with Medicaid financed births are able to remain enrolled in the program and have continuous coverage and better access to care.

- As a condition of receiving increased federal funding from the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, states must meet certain maintenance of eligibility requirements, including providing continuous coverage to Medicaid enrollees who have been enrolled in the program since March 18, 2020 until the end of the COVID19 public health emergency. As a result, postpartum women enrolled in Medicaid since March 2020 continue to have Medicaid coverage. Once the continuous coverage requirements end, however, many of these women are at risk of losing their Medicaid coverage, particularly those living in non-expansion states.

- In recent years, there has been a growing interest in expanding postpartum Medicaid coverage beyond 60 days, in part due to the high rates of maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States and the disproportionately high rates of poor maternal outcomes experienced by Black and Native American pregnant people. The federal American Rescue Act of 2021, gives states the option to extend postpartum coverage to pregnant people to a full year. Coverage begins in April 2022 and states must provide a full-scope of benefits without limitations on coverage during the extension. To date, 21 states have taken steps to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage to 12 months—four additional states either limit the postpartum coverage periods to less the 12 months (GA, TX, WI) or only offer a limited benefits package for postpartum individuals with substance use disorder (MO).

Abortion

The federal Hyde Amendment prohibits federal spending on abortions, except when the pregnancy is a result of rape or incest, or when it jeopardizes the life of the pregnant person (Figure 6). States may use their own unmatched funds to cover abortions in other circumstances. As of January 2022, 33 states and DC follow Hyde restrictions,16 states cover abortions for Medicaid beneficiaries that are considered to be “medically necessary” and pay for these using only state funds. One state, South Dakota, has not covered abortions in cases of rape or incest for 25 years. A January 2019 U.S. Government Accountability (GAO) report found that many states were not covering some abortions that were eligible for Medicaid coverage funding, in violation of federal law. In cases when Medicaid does cover abortions, reimbursement rates tend to be low and do not cover the full cost of the procedure.

In December 2021, the Supreme Court heard Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a case that could overturn the constitutional right to abortion established by the decision in Roe v. Wade. If the court were to overturn the decision in Roe, availability of abortion would be severely limited and unavailable in many parts of the country. The federal Hyde rules would still apply for states that retain abortion availability, and states would still be able to use state dollars to pay for abortions beyond the Hyde restrictions.

Chronic Conditions

As women age, their health needs shift from reproductive care to greater need for screening and management of chronic diseases, mental health care, and disability care (although many women in their reproductive years also have these health needs).

Mental Health

- In 2019, Medicaid covered one in four (24%) adult women with any mental illness and 30% of adult women with a serious mental illness.4

- Medicaid’s behavioral health benefits include acute care services, long-term services, and supports to enable people with chronic illness to receive community-based care. In addition, states with Medicaid expansion programs are required to cover 10 essential health benefits, which include mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment.

Breast and Cervical Cancers

- Under the Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act, states may extend Medicaid coverage for cancer treatment to uninsured women diagnosed with breast or cervical cancer through a federal screening program and receive a federal match for those services. In 2019, over 43,000 women were enrolled in Medicaid through the Breast and Cervical Cancer Program.5

- Preventive services for breast and cervical cancers are required benefits in ACA Medicaid Expansion programs. States are required to cover mammograms and pap tests, genetic (BRCA) screening for high-risk women, and breast cancer preventive medication for high-risk women. Most states cover the screening tests for all beneficiaries. However, coverage for other services such as such as colposcopy following an abnormal pap result and genetic screening for women at higher risk of breast cancer is more uneven across state eligibility pathways.

Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care

Women with disabilities

- Medicaid covers over four in ten (44%) nonelderly women with broad range of physical and mental disabilities, including physical impairments, severe mental illnesses, and specific conditions such as muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, and HIV/AIDS. In addition, Medicaid also covers some nonelderly women who separately also qualify for Medicare coverage due to long-term disabilities (discussed below).

- Benefits that Medicaid covers include: assistance with medical and supportive services including rehabilitation, transportation, and therapeutic services, which help people with disabilities live independently and are not typically covered by private health insurance plans. Long-term services, including home health care, are another critical health benefit for women with disabilities that has very limited coverage through commercial plans but is covered by Medicaid.

Medicare-Medicaid Enrollees and LONG-TERM Care

Medicare provides health coverage to people 65 and older and younger people with long-term disabilities. In 2019, Medicaid provided coverage to more than 12 million Medicare beneficiaries (20% of all Medicare beneficiaries) with low incomes and modest assets. Of this total, women of all ages account for 59% of this group (women 65 and older account for 40%) (Figure 8).6 Many of these beneficiaries have extensive and costly health needs.

- The majority of dually eligible beneficiaries qualify for full Medicaid benefits and may receive coverage for services that Medicare does not currently cover, such as dental and vision care, and long-term services and supports. Other dually eligible beneficiaries may only receive assistance with their Medicare premiums and/or cost sharing through the Medicare Savings Programs, but not full Medicaid benefits, if they meet an income and asset test.

- Medicaid covers a continuum of long-term services and supports ranging from home and community based services (HCBS) that allow persons to live independently in their own homes or in other community settings to institutional care provided in nursing facilities and intermediate care facilities for individuals with intellectual disabilities. In FY2019, HCBS represented 59% of total Medicaid expenditures on long-term services and supports (LTSS).

- Since women are more likely to live longer and experience higher rates of chronic illness and disability than men, they are more likely to require long-term services in their lifetime. Approximately two-thirds of nursing home residents (65%) and people receiving home health care (61%) are women. Medicaid coverage provides access to these long-term services, which would otherwise be unaffordable for women with fixed incomes (in 2020, nursing home care averaged more than $93,075 annually for a semi-private room).

Access to Care

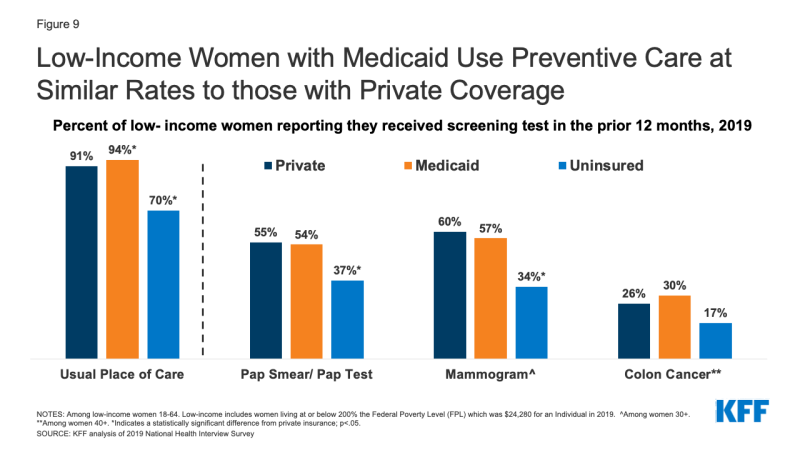

Compared to their uninsured counterparts, women with Medicaid experience fewer barriers to care and on several measures have utilization rates comparable to low-income women with private insurance.

- Women on Medicaid use primary and preventive health services, such as pap smears and mammograms, at rates comparable to women with private insurance and at higher rates than uninsured women (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Low-Income Women with Medicaid Use Preventive Care at Similar Rates to those with Private Coverage

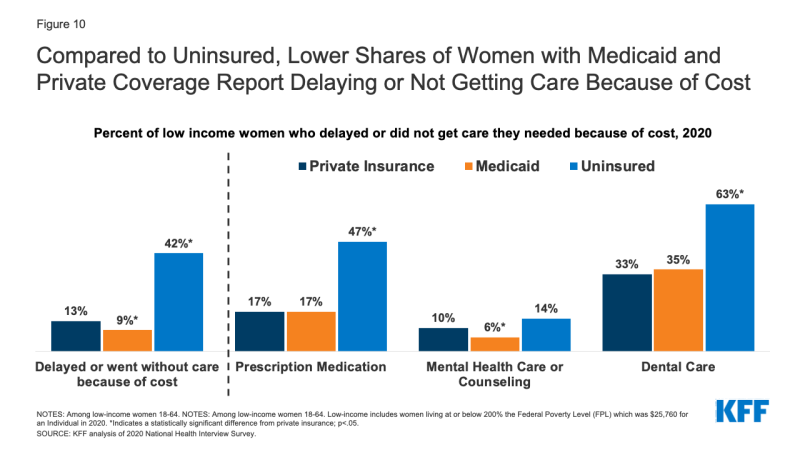

- Women on Medicaid are less likely than uninsured women to experience cost barriers. Compared to low-income women with private insurance, women on Medicaid were less likely to report that they delayed or went without care due to cost, likely attributable to the fact that Medicaid does not charge deductibles, rarely charges premiums and has only nominal cost-sharing. Affordability, however, is still a problem for some women in the program because they are typically low-income and have to pay out of pocket costs in states that impose caps on the number of covered visits or prescriptions or charge copayments for prescription drugs (for non-pregnant adults). One in 10 low-income women on Medicaid report that they had not filled a prescription (10%) in the past year because of the cost (Figure 10).

Endnotes

138% of FPL in 2021 is $17,774 for an individual and $30,305 for a family of three.

KFF analysis of calendar year 2019 TMSIS.

FY 2022 FMAPs reflect higher federal matching funding made available through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (amended by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act). The additional funds are available to states from January 1, 2020 until the end of the public health emergency period for the COVID-19 pandemic. This act provided a 6.2 percentage-point increase to all FMAP rates for all states (including DC). For more information on the FMAP increase during the COVID-19 pandemic, see Key Questions About the New Increase in Federal Medicaid Matching Funds for COVID-19.

KFF analysis of National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2019.

KFF analysis of calendar year 2019 TMSIS.

Ibid.