Medicaid Coverage of and Spending on GLP-1s

GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) drugs have been used as a treatment for type 2 diabetes for over a decade, but newer forms of these drugs have gained widespread attention for their effectiveness as a treatment for obesity. While these drugs have provided new opportunities for obesity treatment, they have also raised questions about access to and affordability of these drugs. These drugs are expensive when purchased out of pocket, and coverage in Medicaid, ACA Marketplace plans, and most large employer firms remains limited, though a number of state Medicaid programs and other payers are re-evaluating their coverage policies. Expanding Medicaid coverage of these drugs could increase access for the almost 40% of adults and 26% of children with obesity in Medicaid. At the same time, expanded coverage could also increase Medicaid drug spending and put pressure on overall state budgets. In the longer term, however, reduced obesity rates among Medicaid enrollees could also result in reduced Medicaid spending on chronic diseases associated with obesity, such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and types of cancer. This brief discusses Medicaid coverage of GLP-1s, examines recent trends in Medicaid prescriptions and gross spending on GLP-1s, and explores the potential implications of expanding coverage obesity drugs for Medicaid programs.

Does Medicaid cover GLP-1s for obesity treatment?

States can decide whether to cover obesity drugs under Medicaid. Under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, Medicaid programs must cover nearly all of a participating manufacturer’s Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs for medically accepted indications. However, weight-loss drugs are included in a small group of drugs that can be excluded from coverage1. Though the statutory exception refers to agents used for “weight loss”, “obesity drugs” is used to refer to this group of medications in this analysis. The FDA has approved three GLP-1s for the treatment of obesity, Saxenda (liraglutide), Wegovy (semaglutide), and Zepbound (tirzepatide), and state Medicaid coverage of these is optional. However, Medicaid programs have to cover formulations to treat type 2 diabetes, including Ozempic (semaglutide), Rybelsus (semaglutide), Victoza (lirglutide), and Mounjaro (tirzepatide). Wegovy, as of March 2024, must also be covered for preventing heart attacks or strokes in adults with cardiovascular disease; however, this expanded label indication does not impact this analysis as it only includes data through 2023. Notably, all obesity drugs are covered for children under Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit, though it is less clear how states are implementing and covering in practice.

Obesity drug coverage in Medicaid remains limited, with 13 state Medicaid programs covering GLP-1s for obesity treatment as of August 2024 (Figure 1). Twelve states in KFF’s annual budget survey reported coverage of GLP-1s for obesity treatment under FFS as of July 1, 2024, and North Carolina reported adding coverage in August of 2024. All 12 states that reported coverage of GLP-1s as of July 1, 2024 also reported that utilization control(s) applied, with the most common being prior authorization (11 of 12 states) and/or BMI requirements (11 of 12 states). Eleven of the 12 states reported covering all three GLP-1s currently approved for the treatment of obesity (Saxenda, Wegovy, or Zepbound). While the survey only asked about FFS coverage, MCO drug coverage must be consistent with the amount, duration, and scope of FFS coverage. MCOs, however, may apply differing utilization controls and medical necessity criteria unless the state’s MCO contract specifies otherwise. Coverage among other payers also remains limited. Recent KFF analysis also found most large employer firms do not cover GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, coverage in ACA Marketplace plans remains limited, and coverage in Medicare is prohibited.

How have Medicaid prescriptions and gross spending on GLP-1s changed in recent years?

The number of Medicaid prescriptions and gross spending on GLP-1s have increased rapidly in recent years, with both nearly doubling from 2022 to 2023. Overall, from 2019 to 2023, the number of GLP-1 prescriptions increased by more than 400%, while gross spending increased by over 500%. Spending per prescription before rebates reached more than $900 per prescription in 2023. Those prices and spending numbers do not account for rebates, and states are likely receiving substantial rebates on these brand drugs. While rebate data for specific drugs is not publicly available, Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) analysis of FY 2020 data found statutory rebates accounted for 61.6% of gross Medicaid spending on brand drugs. Also, amid growing criticism of the cost of their drugs, Novo Nordisk, the company that creates Ozempic and Wegovy, has said that rebates and other fees (across all payers) account for about 40% of the cost of the two drugs. The GLP-1s in this analysis still account for relatively small shares of the total number of Medicaid prescriptions and spending before rebates, though the shares are growing. By 2023, these drugs accounted for 0.5% of all Medicaid prescriptions (up from 0.01% in 2019) and 3.7% of all gross Medicaid spending (up from 0.9% in 2019).

Specifically, increased utilization of Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro have contributed substantially to recent growth. Prescriptions and spending on Ozempic, approved to help control blood sugar levels for adults with type 2 diabetes in 2017 (Table 1), have grown considerably from 2019 to 2023, nearly doubling every year since 2019. Looking from 2022 to 2023, the latest year of data available, Wegovy (first approved in 2021) and Mounjaro (approved in 2022) also saw substantial growth, with prescriptions and gross spending for both drugs increasing twelvefold or more. This analysis includes GLP-1 formulations approved for obesity treatment as well as the same formulations approved for type 2 diabetes (for more information on how GLP-1s are identified in this analysis, see Methods). From Medicaid data publicly available, there is no way yet to disentangle how much of the growing use of GLP-1s is related to treatment for diabetes versus obesity, or a combination of both. In addition, the popularity and increased demand for GLP-1s has led to drug shortages, sometimes causing people to switch products or ration doses or sometimes leaving individuals without access to needed prescriptions. This may have implications for drug trends, though the FDA recently reported that GLP-1 supplies are beginning to stabilize.

How may the coverage landscape of GLP-1s for obesity treatment change?

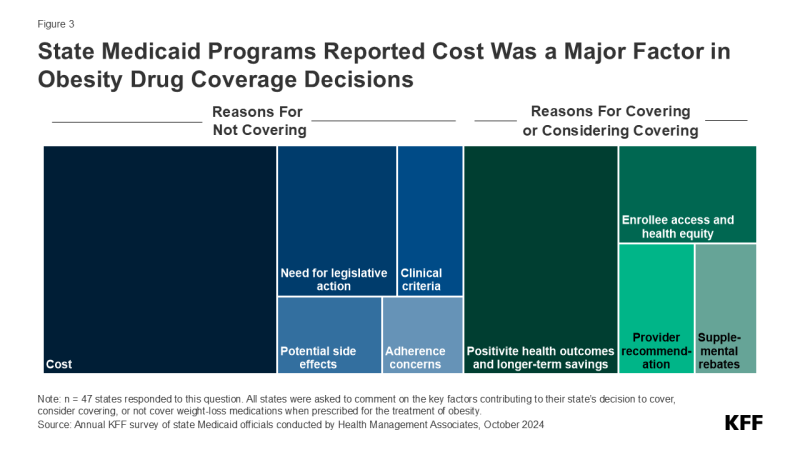

Many state Medicaid programs are considering covering obesity drugs in the future but are concerned about the cost implications. KFF’s annual budget survey found that, among those states that do not currently cover obesity drugs, half reported they were considering adding coverage, with a few states reporting plans to add or expand coverage in FY 2025 or later. When asked about the key factors contributing to their obesity medication coverage decision, almost two-thirds of responding states mentioned cost, though states are also weighing a number of other factors including the need for legislative action, adherence concerns, clinical criteria development, and potential side effects. Conversely, 4 in 10 states noted that positive health outcomes and longer-term savings on chronic diseases associated with obesity were key factors in their decision to cover or consider covering in the future along with increasing enrollee access and health equity, recommendations from providers, and ability to negotiate supplemental rebate agreements. States are likely considering various cost containment strategies for these drugs and may even be re-evaluating their broader approach to obesity treatment, including the use of obesity medications along with other treatments such as nutritional counseling or behavioral therapy. Obesity is caused by a multitude of complex factors, and uptake of GLP-1s could improve health but would not address all of the underlying contributors to obesity.

Methods |

| Number of Prescriptions and Gross Spending Data: This analysis uses 2019 through 2023 State Drug Utilization Data (SDUD) (downloaded in October 2024). The SDUD is publicly available data provided as part of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), and provides information on the number of prescriptions, Medicaid spending before rebates, and cost-sharing for rebate-eligible Medicaid outpatient drugs by NDC, quarter, managed care or fee-for-service, and state. It also provides this data summarized for the whole country. The data do not include information on the number of days supplied in each prescription. CMS has suppressed SDUD cells with fewer than 11 prescriptions, citing the Federal Privacy Act and the HIPAA Privacy Rule. This analysis used the national totals data because less data is suppressed at the national versus state level.

Identifying GLP-1s: GLP-1 agonists included in the analysis were approved for treatment of obesity, Saxenda (liraglutide), Wegovy (semaglutide), Zepbound (tirzepatide) and corresponding formulations that may potentially be used off-label for treatment of obesity, Mounjaro (tirzepatide), Ozempic (semaglutide), Rybelsus (semaglutide), Victoza (liraglutide), mirroring another recent KFF analysis. Other GLP-1 agonists with active ingredients only approved for treatment of diabetes that have less potential for off-label weight loss use (such as Bydureon BCise, Trulicity) were not included. Limitations: There are a few limitations to the estimates of Medicaid prescriptions and gross spending found in this analysis, including:

|

Endnotes

Drugs that may be excluded from coverage under the MDRP include drugs used for: a) anorexia, weight loss, or weight gain, b) promoting fertility, c) cosmetic purposes or hair growth, d) symptomatic relief of cough and colds, e) prescription vitamins and mineral products except prenatal vitamins and fluoride preparations , f) nonprescription drugs, g) a manufacturer’s covered outpatient drug in which tests and monitoring services have to be purchased from that manufacturer, h) sexual or erectile dysfunction unless used to treat a condition. For more information see, 42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8.