2014 Employer Health Benefits Survey

Published:

Abstract

The 2015 Employer Health Benefits Survey was released September 22, 2015.

This annual survey of employers provides a detailed look at trends in employer-sponsored health coverage, including premiums, employee contributions, cost-sharing provisions, and employer opinions. The 2014 survey included almost three thousand interviews with non-federal public and private firms.

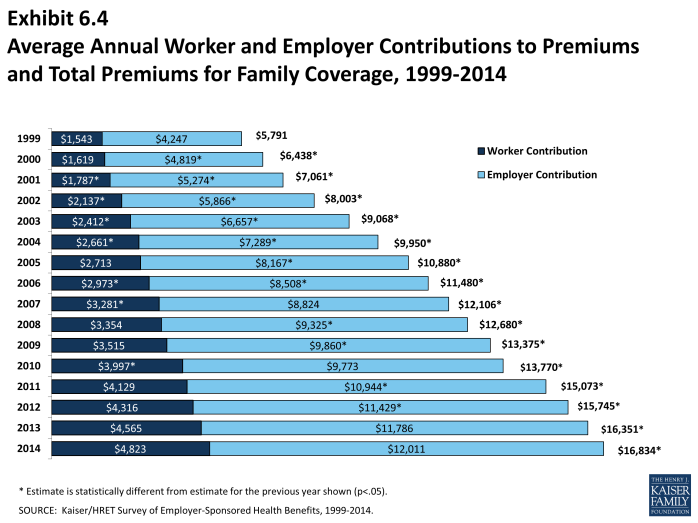

Annual premiums for employer-sponsored family health coverage reached $16,834 this year, up 3 percent from last year, with workers on average paying $4,823 towards the cost of their coverage, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research & Educational Trust (HRET) 2014 Employer Health Benefits Survey. Survey results are released here in a variety of ways, including a full report with downloadable tables, summary of findings, and an article published in the journal Health Affairs.

News Release

- A news release announcing the publication of the 2014 Employer Health Benefits Survey is available here.

Summary of Findings

- The Summary of Findings provides an overview of the 2014 survey results and is available under the Summary of Findings tab or as a pdf file in the “Download” box to the right.

Full Report

- The complete Employer Health Benefits Survey Report includes over 200 exhibits and is available under the Report tab or as a pdf file in the “Download” box to the right. The “Report” tab contains 14 separate sections. Users can also download each section separately from the “Download” box or download the complete set of section exhibits from the bottom of the respective section page.

Health Affairs

- The peer-reviewed journal Health Affairs has published an article with key findings from the 2014 survey: Health Benefits in 2014: Stability In Premiums And Coverage For Employer-Sponsored Plans.

Web Briefing

- On Wednesday, September 10, 2014, the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research & Educational Trust (HRET) held a reporters-only web briefing to release the 2014 Employer Health Benefits Survey.

Interactive Graphic

- This graphing tool allows users to look at changes in premiums and worker contributions for covered workers at different types of firms, over time: Premiums and Worker Contributions Among Workers Covered by Employer-Sponsored Coverage, 1999-2014.

Key Exhibits – Chartpack

- Over twenty overview slides from the 2014 Employer Health Benefits Survey are available as a slideshow or as pdf.

Additional Resources

- Standard errors for selected estimates are available in the Technical Supplement here.

- Employer Health Benefits Surveys from 1998-2013 are available here. Please note that historic survey reports have not been revised with methodological changes.

- Researchers may request for a public use dataset by going to Contact Us and choosing “TOPIC: Health Costs.”

Researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation, NORC at the University of Chicago, and Health Research & Educational Trust designed and analyzed the survey.

Summary of Findings

Employer-sponsored insurance covers about 149 million nonelderly people.1 To provide current information about employer-sponsored health benefits, the Kaiser Family Foundation (Kaiser) and the Health Research & Educational Trust (HRET) conduct an annual survey of private and nonfederal public employers with three or more workers. This is the sixteenth Kaiser/HRET survey and reflects employer-sponsored health benefits in 2014.

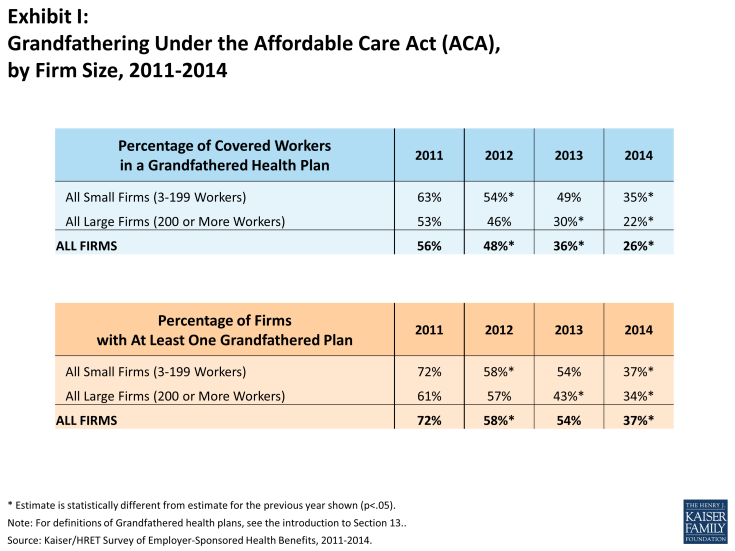

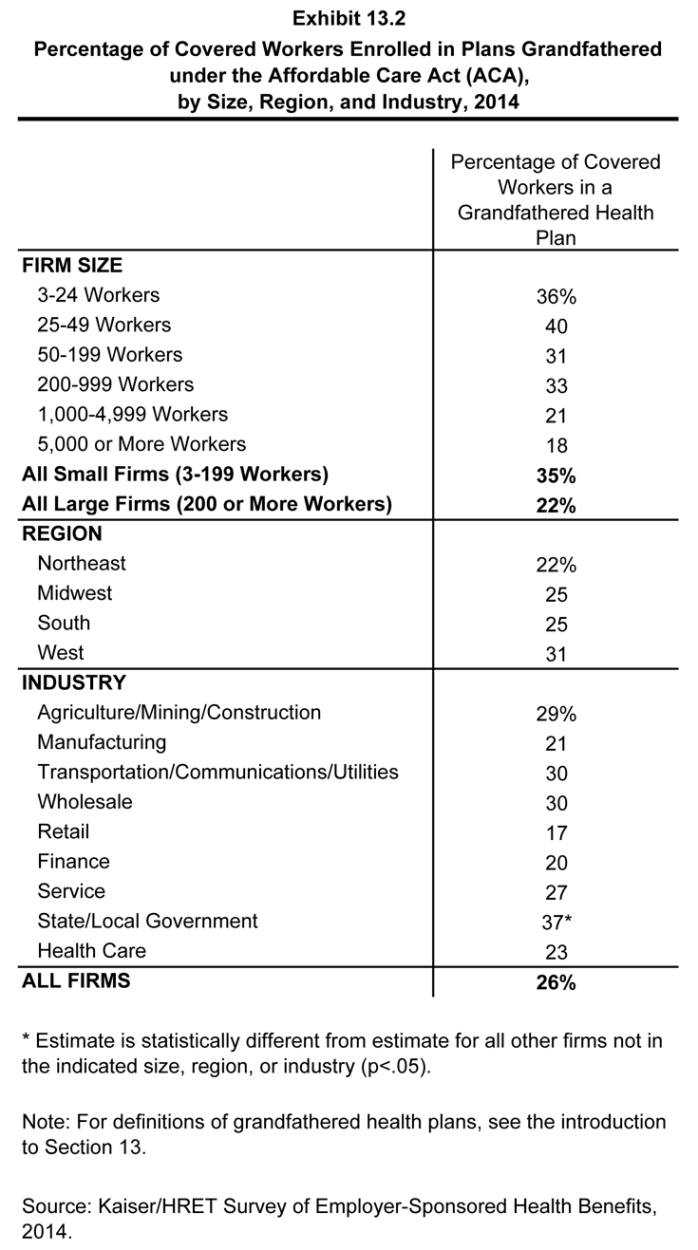

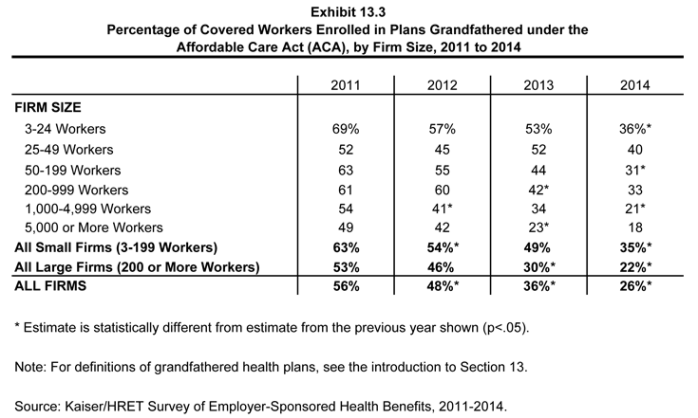

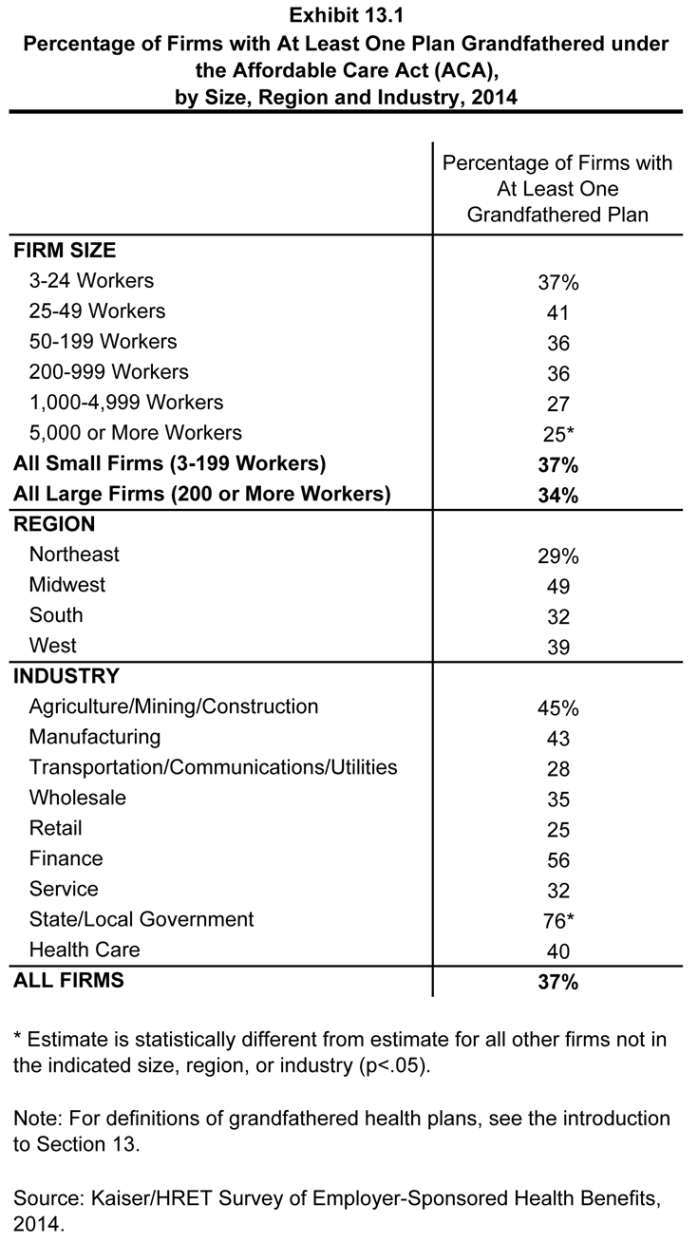

The key findings from the survey, conducted from January through May 2014, include a modest increase in the average premiums for family coverage (3%). Single coverage premiums are 2% higher than in 2013, but the difference is not statistically significant. Covered workers generally face similar premium contributions and cost-sharing requirements in 2014 as they did in 2013. The percentage of firms (55%) which offer health benefits to at least some of their employees and the percentage of workers covered at those firms (62%) are statistically unchanged from 2013. The percentage of covered workers enrolled in grandfathered health plans – those plans exempt from many provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – declined to 26% of covered workers from 36% in 2013. Perhaps in response to new provisions of the ACA, the average length of the waiting period decreased for those with a waiting period and the percentage with an out-of-pocket limit increased. Although employers continue to offer coverage to spouses, dependents and domestic partners, some employers are instituting incentives to influence workers’ enrollment decisions, including nine percent of employers who attach restrictions for spouses’ eligibility if they are offered coverage at another source, or nine percent of firms who provide additional compensation if employees do not enroll in health benefits.

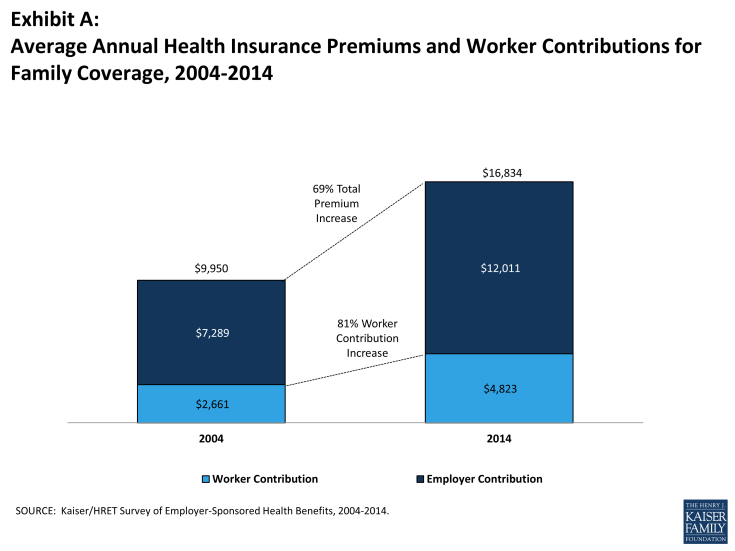

HEALTH INSURANCE PREMIUMS AND WORKER CONTRIBUTIONS

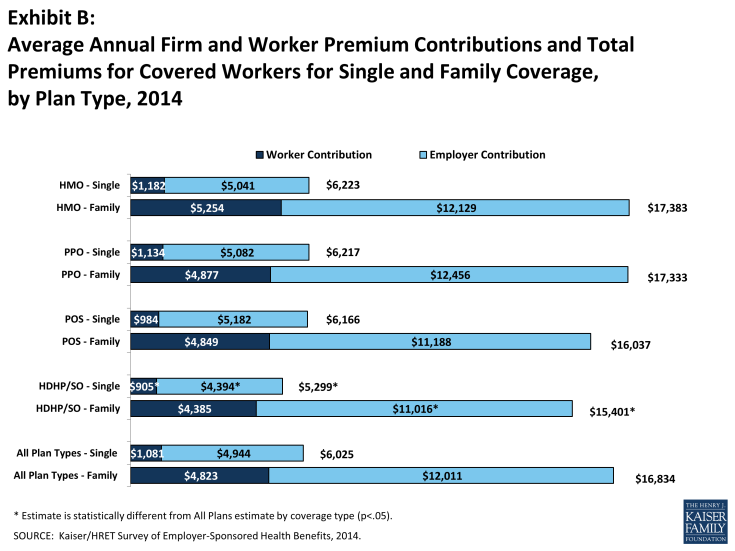

In 2014, the average annual premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance are $6,025 for single coverage and $16,834 for family coverage. The average family premium rose 3% over the 2013 average premium. Single coverage premiums rose 2% in 2014 but are not statistically different than the 2013 premium amounts. During the same period, workers’ wages increased 2.3% and inflation increased 2%.2 Over the last ten years, the average premium for family coverage has increased 69% (Exhibit A). Premiums have increased less quickly over the last five years (2009 to 2014), than the preceding five year period (2004 to 2009) (26% vs. 34%).

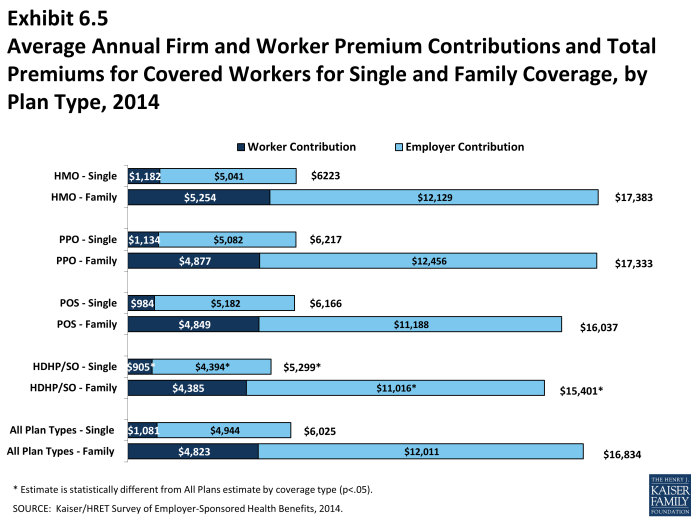

Average premiums for high-deductible health plans with a savings option (HDHP/SOs) are lower than the overall average for all plan types for both single and family coverage (Exhibit B), at $5,299 and $15,401, respectively. There are important differences in premiums by firm size: the average premium for family coverage is lower for covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) than for workers in larger firms ($15,849 vs. $17,265).

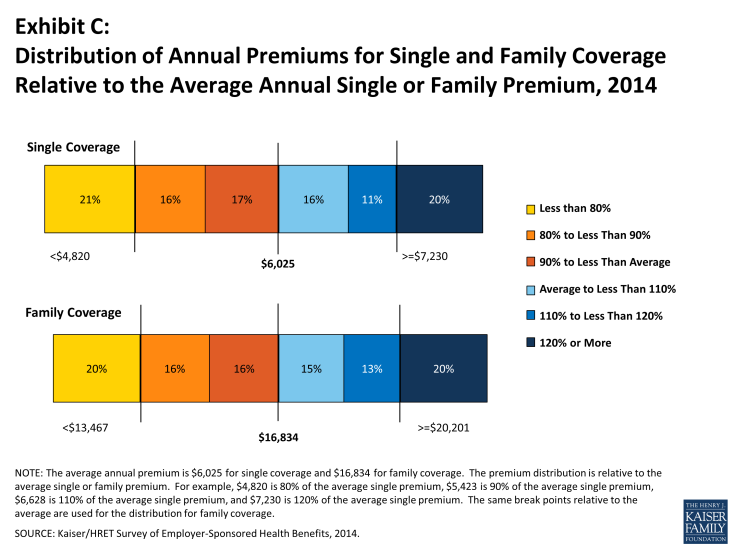

Premiums vary significantly around the averages for single and family coverage, resulting from differences in benefits, cost sharing, covered populations, and geographical location. Twenty percent of covered workers are in plans with an annual total premium for family coverage of at least $20,201 (120% of the average family premium), and 20% of covered workers are in plans where the family premium is less than $13,467 (80% of the average family premium). The distribution is similar around the average single premium (Exhibit C).

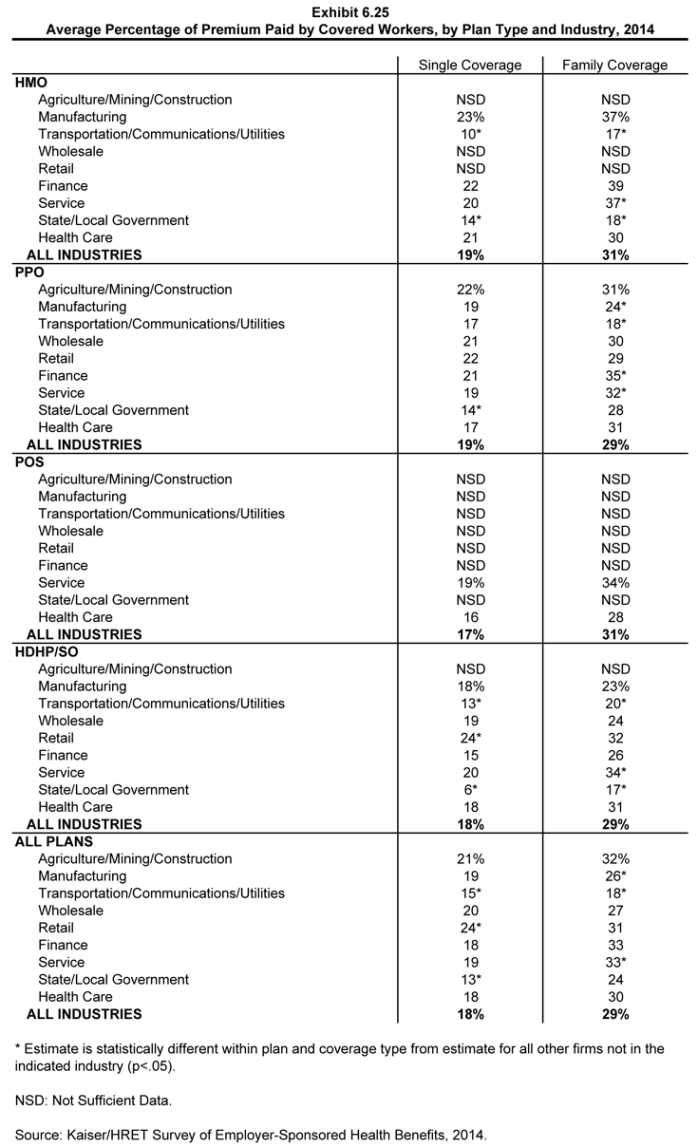

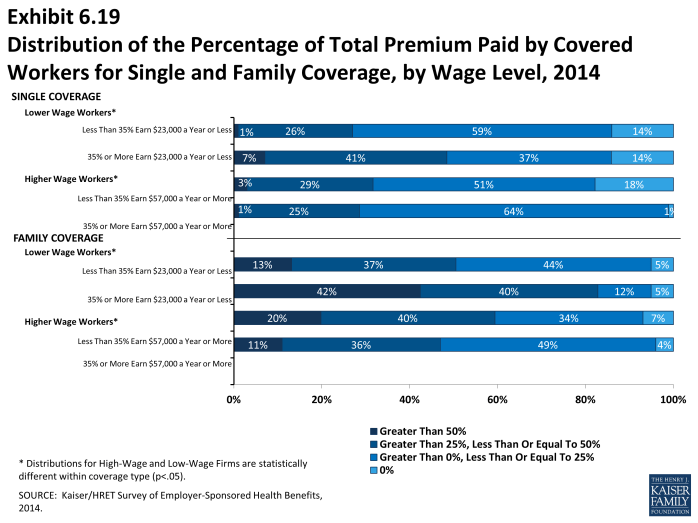

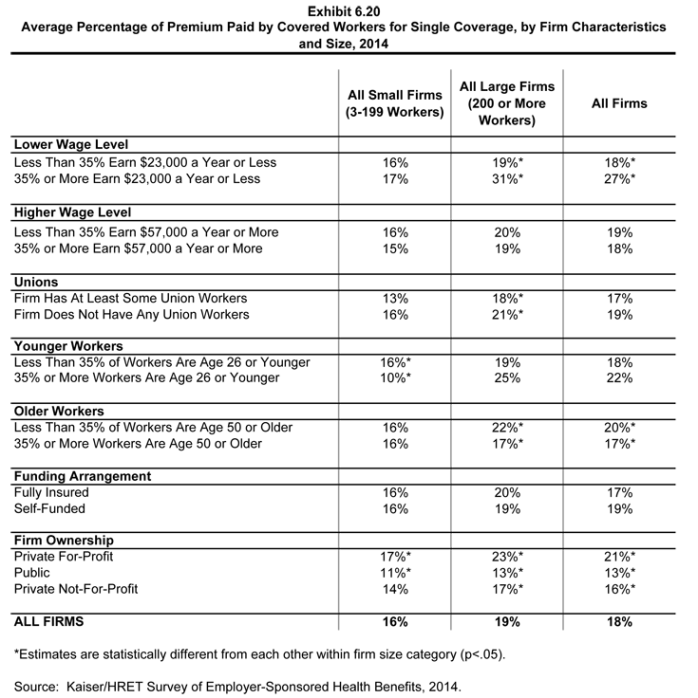

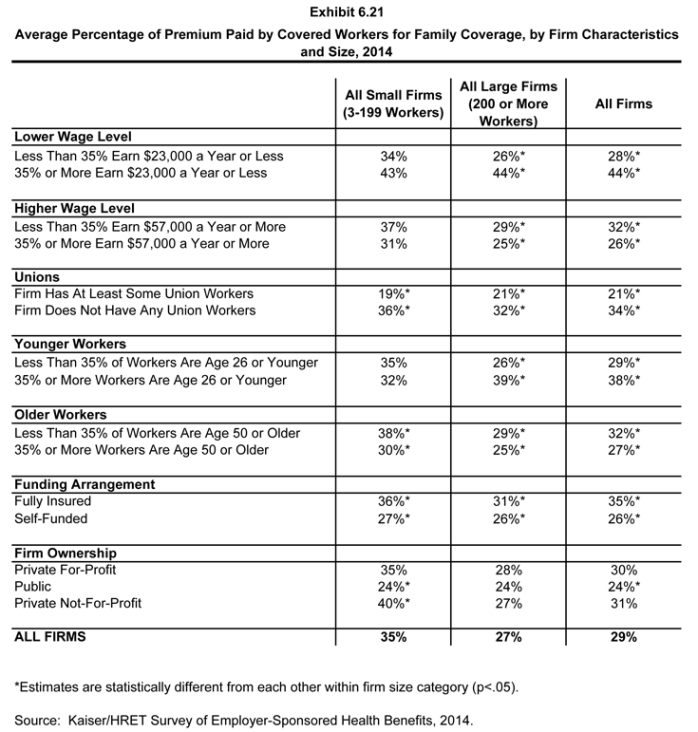

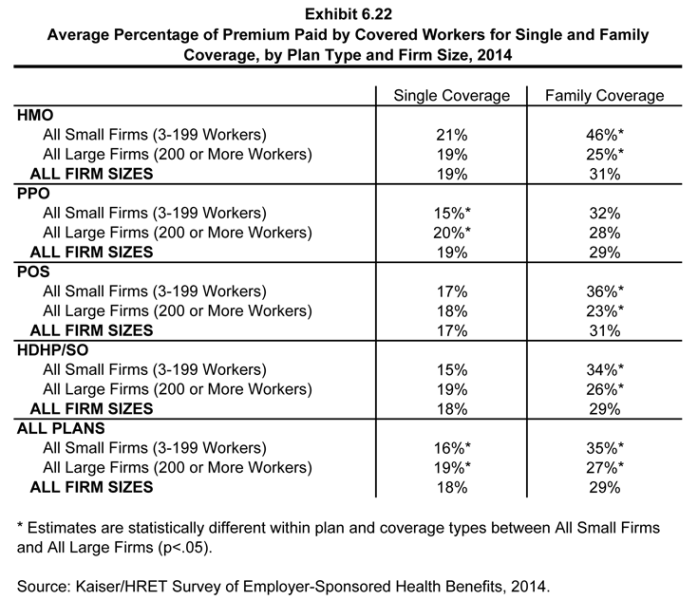

Most often, employers require that workers make a contribution towards the cost of the premium. Covered workers contribute on average 18% of the premium for single coverage and 29% of the premium for family coverage, the same percentages as 2013. Workers in small firms (3 – 199 workers) contribute a lower average percentage for single coverage compared to workers in larger firms (16% vs. 19%), but they contribute a higher average percentage for family coverage (35% vs. 27%). Workers in firms with a higher percentage of lower-wage workers (at least 35% of workers earn $23,000 or less) contribute higher percentages of the premium for single coverage (27% vs. 18%) and for family coverage (44% vs. 28%) than workers in firms with a smaller share of lower-wage workers.

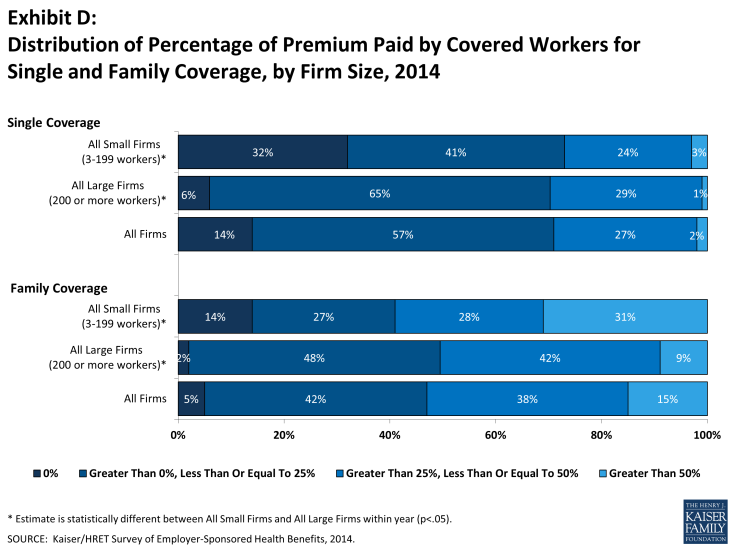

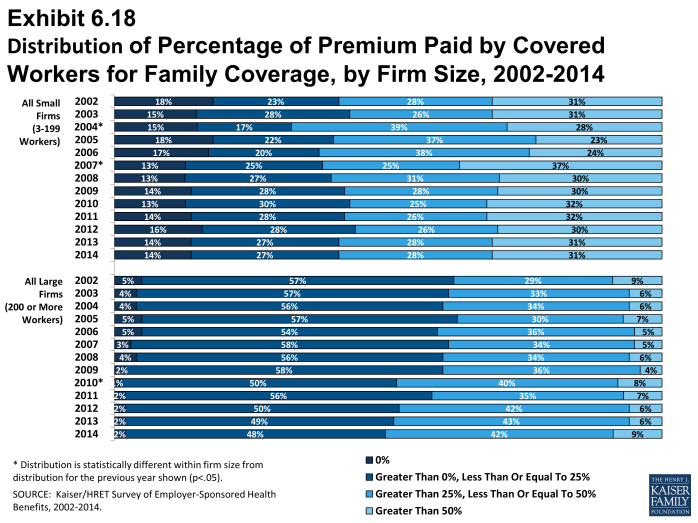

As with total premiums, the share of the premium contributed by workers varies considerably among firms. For single coverage, 57% of covered workers are in plans that require them to make a contribution of less than or equal to a quarter of the total premium, 2% are in plans that require a contribution of more than half of the premium, and 14% are in plans that require no contribution at all. For family coverage, 42% of covered workers are in plans that require them to make a contribution of less than or equal to a quarter of the total premium and 15% are in plans that require more than half of the premium, while only 5% are in plans that require no contribution at all for family coverage (Exhibit D).

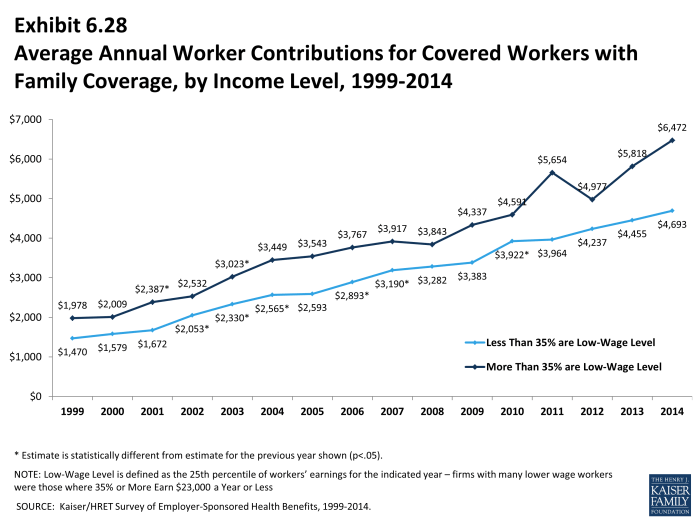

Looking at the dollar amounts that workers contribute, the average annual premium contributions in 2014 are $1,081 for single coverage and $4,823 for family coverage. Covered workers’ average dollar contribution to family coverage has increased 81% since 2004 and 37% since 2009 (Exhibit A). Workers in small firms (3 – 199 workers) have lower average contributions for single coverage than workers in larger firms ($902 vs. $1,160), but higher average contributions for family coverage ($5,508 vs. $4,523). Workers in firms with a higher percentage of lower-wage workers (at least 35% of workers earn $23,000 or less) have higher average contributions for family coverage ($6,472 vs. $4,693) than workers in firms with lower percentages of lower-wage workers.

PLAN ENROLLMENT

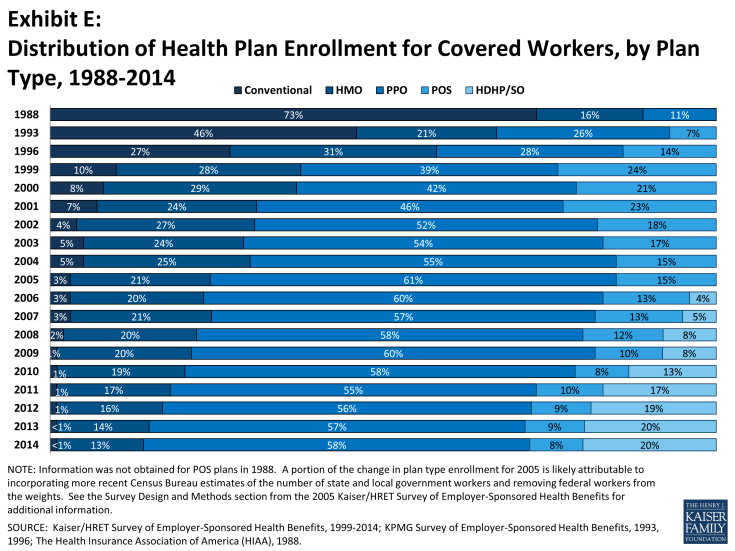

PPO plans remain the most common plan type, enrolling 58% of covered workers in 2014. Twenty percent of covered workers are enrolled in a high-deductible plan with a savings options (HDHP/SO), 13% in an HMO, 8% in a POS plan, and less than 1% in a conventional (also known as an indemnity plan) (Exhibit E). Enrollment in HDHP/SOs increased significantly between 2009 and 2011, from 8% to 17% of covered workers, but has plateaued since then (Exhibit E). In 2014, twenty-seven percent of firms offering health benefits offer a high-deductible health plan with a health reimbursement arrangement (HDHP/HRA) or a health savings account (HSA) qualified HDHP.

Enrollment distribution varies by firm size; for example, PPOs are relatively more popular for covered workers at large firms (200 or more workers) than smaller firms (63% vs. 46%) and POS plans are relatively more popular among smaller firms than large firms (17% vs. 4%).

EMPLOYEE COST SHARING

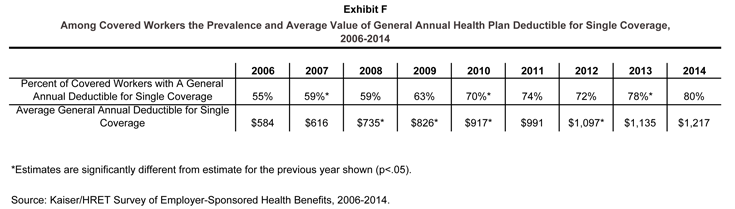

Most covered workers face additional out-of-pocket costs when they use health care services. Eighty percent of covered workers have a general annual deductible for single coverage that must be met before most services are reimbursed by the plan. Even workers without a general annual deductible often face other types of cost sharing when they use services, such as copayments or coinsurance for office visits and hospitalizations.

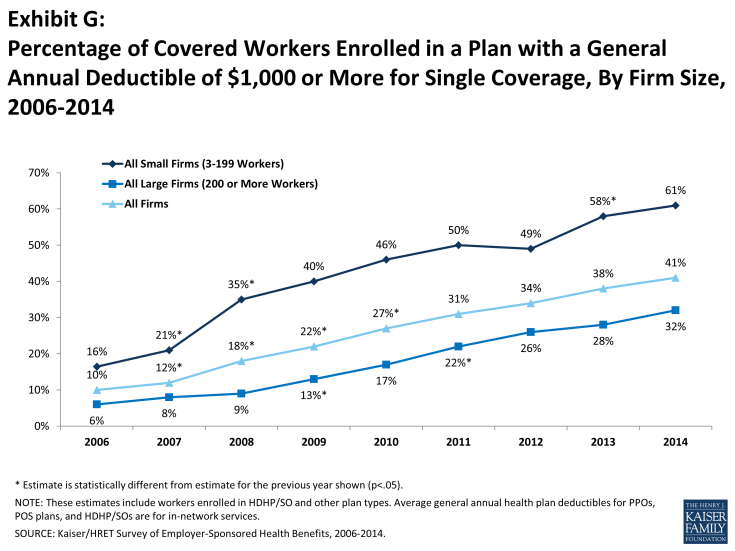

Among covered workers with a general annual deductible, the average deductible amount for single coverage is $1,217. The average annual deductible is unchanged from last year ($1,135), but has increased from $826 dollars in 2009. Deductibles differ by firm size: for workers in plans with a deductible, the average deductible for single coverage is $1,797 in small firms (3-199 workers), compared to $971 for workers in larger firms (Exhibit F). Covered workers in small firms are significantly more likely to have high general annual deductibles compared to those in larger firms. Sixty-one percent of covered workers in small firms are in a plan with a deductible of at least $1,000 for single coverage compared to 32% in larger firms; a similar pattern is seen for those in plans with a deductible of at least $2,000 (34% for small firms vs. 11% for larger firms) (Exhibit G).

The large majority of workers also have to pay a portion of the cost of physician office visits. Almost three-in-four covered workers pay a copayment (a fixed dollar amount) for office visits with a primary care physician (73%) or a specialist physician (72%), in addition to any general annual deductible their plan may have. Smaller shares of workers pay coinsurance (a percentage of the covered amount) for primary care office visits (18%) or specialty care visits (21%). For in-network office visits, covered workers with a copayment pay an average of $24 for primary care and $36 for specialty care. For covered workers with coinsurance, the average coinsurance for office visits is 18% for primary and 19% for specialty care. While the survey collects information only on in-network cost sharing, it is generally understood that out-of-network cost sharing is higher.

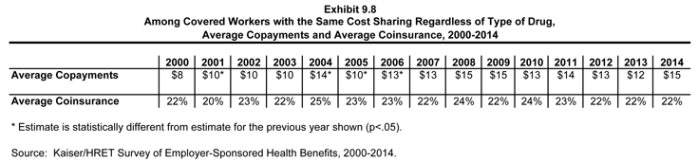

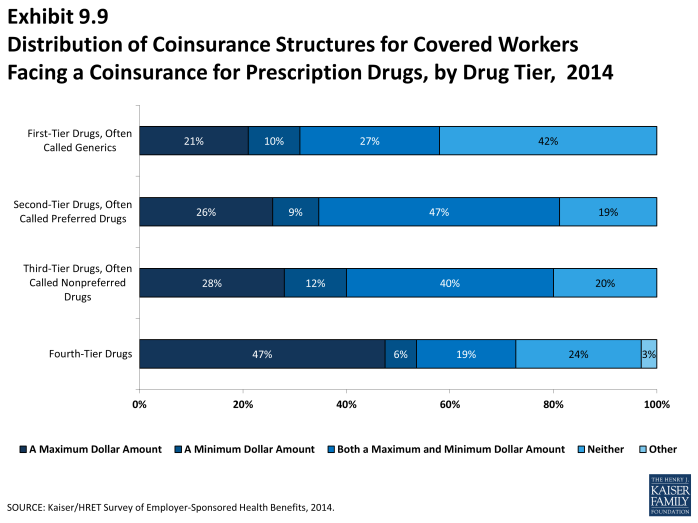

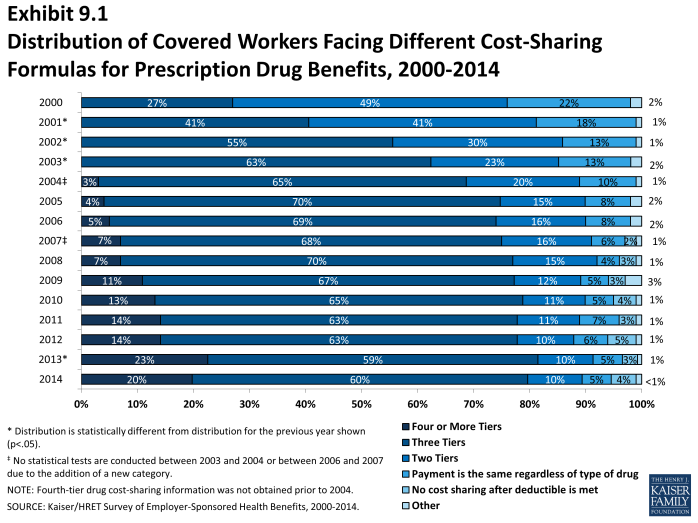

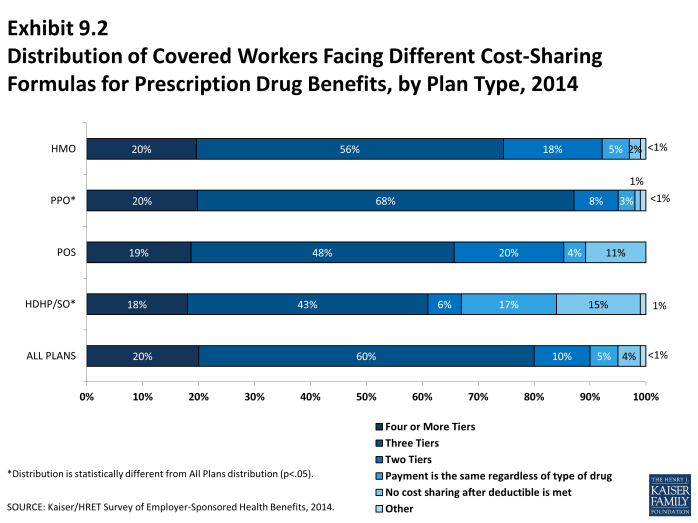

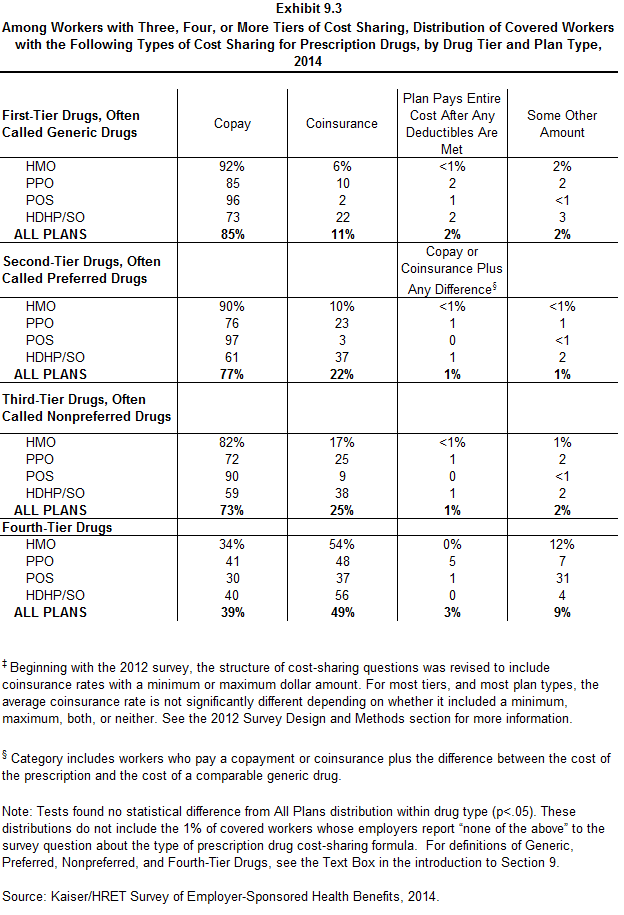

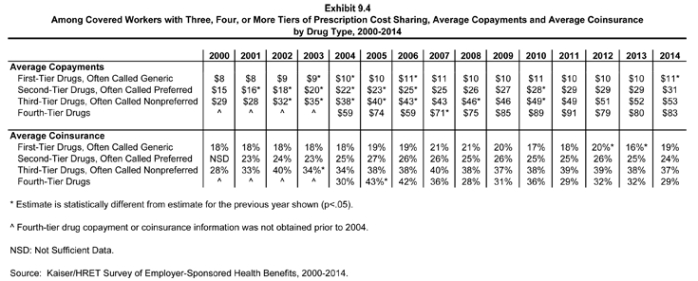

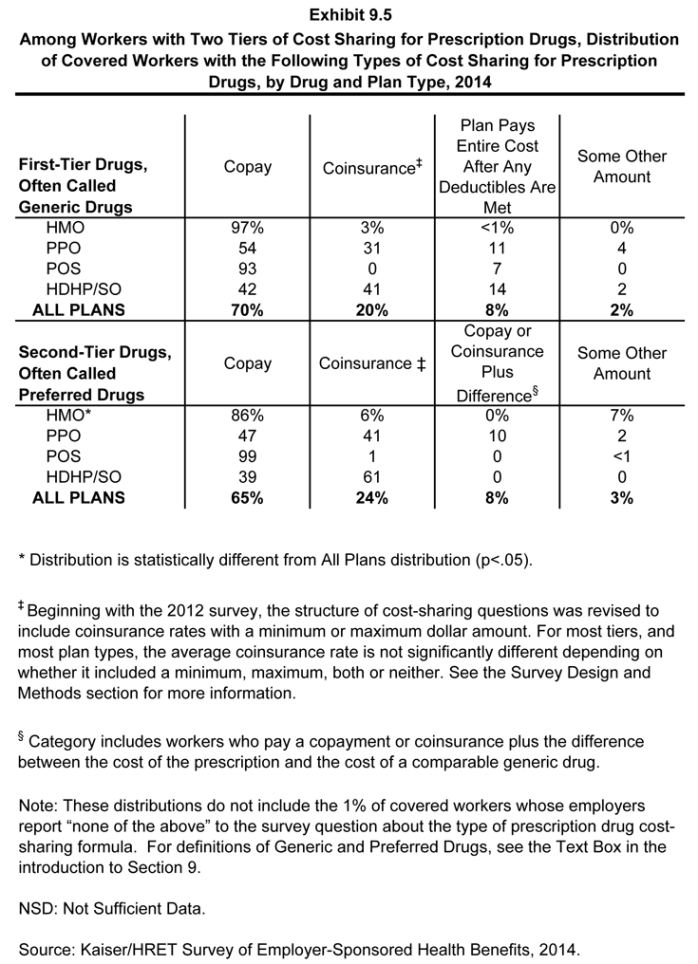

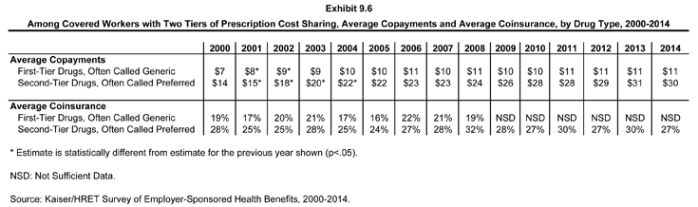

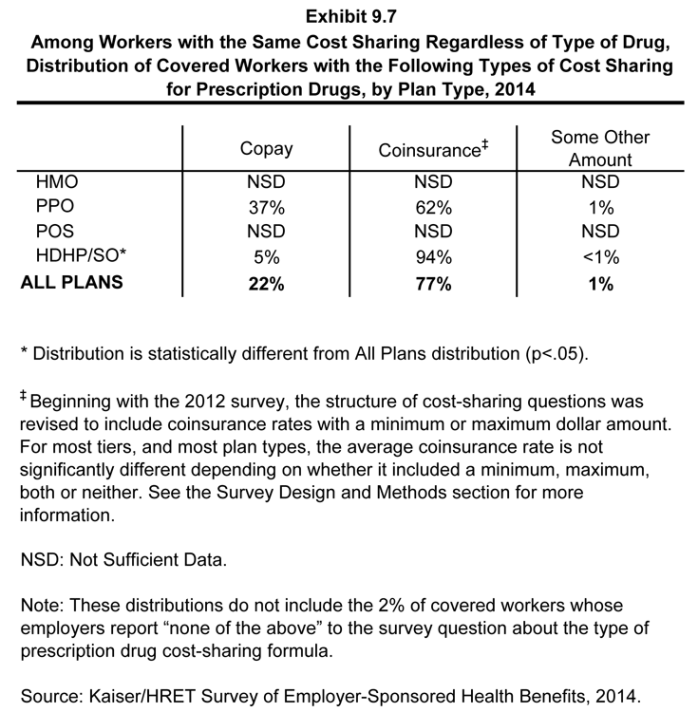

The cost sharing that a person pays when they fill a prescription usually varies with the type of drug – for example whether it is a generic, brand-name, or specialty drug – and whether the drug is considered preferred or not on the plan’s formulary. These factors result in each drug being assigned to a tier that represents a different level, or type, of cost sharing. Eighty percent of covered workers are in plans with three-or-more tiers of cost sharing. Copayments are the most common form of cost sharing for tiers one through three and coinsurance is the most common form of cost sharing for drugs on the fourth or higher tier of formularies. Among workers with three-or-more tier plans, the average copayments in these plans are $11 for first-tier drugs, $31 for second-tier drugs, $53 for third-tier drugs, and $83 for fourth-tier drugs. Apart from first-tier drugs, the average copayment amounts are similar to those reported last year. HDHP/SOs have a somewhat different cost-sharing pattern for prescription drugs than other plan types: just 62% of covered workers are enrolled in a plan with three-or-more tiers of cost sharing, while 15% are in plans that pay the full cost of prescriptions once the plan deductible is met, and 17% are in a plan with the same cost sharing for all prescription drugs.

Most workers also face additional cost sharing for a hospital admission or an outpatient surgery episode. After any general annual deductible is met, 62% of covered workers have a coinsurance and 15% have a copayment for hospital admissions. Lower percentages have per day (per diem) payments (5%), a separate hospital deductible (3%), or both copayments and coinsurance (10%). The average coinsurance rate for hospital admissions is 19%, the average copayment is $280 per hospital admission, the average per diem charge is $297, and the average separate annual hospital deductible is $490. The cost-sharing provisions for outpatient surgery are similar to those for hospital admissions, as most covered workers have either coinsurance (64%) or copayments (16%). For covered workers with cost sharing for each outpatient surgery episode, the average coinsurance is 19% and the average copayment is $157.

Most plans limit the amount of cost sharing workers must pay each year, generally referred to as an out-of-pocket maximum. The ACA, requires that non-grandfathered health plans, with a plan year starting in 2014 have an out-of-pocket maximum of $6,350 or less for single coverage and $12,700 for family coverage or less. In 2014, 94% percent of covered workers have an out-of-pocket maximum for single coverage, significantly more than 88% in 2013. While most workers have out-of-pocket limits, the actual dollar limits differ considerably. For example, among covered workers in plans that have an out-of-pocket maximum for single coverage, 54% are in plans with an annual out-of-pocket maximum of $3,000 or more, and 10% are in plans with an out-of-pocket maximum of less than $1,500.

AVAILABILITY OF EMPLOYER-SPONSORED COVERAGE

Fifty-five percent of firms offer health benefits to their workers, statistically unchanged from 57% last year and 61% in 2012 (Exhibit H). The likelihood of offering health benefits differs significantly by size of firm, with only 44% of employers with 3 to 9 workers offering coverage, but virtually all employers with 1,000 or more workers offering coverage to at least some of their employees. Ninety percent of workers are in a firm that offers health benefits to at least some of its employees, similar to 2013 (90%). Offer rates also differ by other firm characteristics; 53% of firms with relatively fewer younger workers (less than 35% of the workers are age 26 or younger) offer health benefits compared to 30% of firms with a higher share of younger workers.

Even in firms that offer health benefits, not all workers are covered. Some workers are not eligible to enroll as a result of waiting periods or minimum work-hour rules. Other workers do not enroll in coverage offered to them because of the cost of coverage or because they are covered through a spouse. Among firms that offer coverage, an average of 77% of workers are eligible for the health benefits offered by their employer. Of those eligible, 80% take up their employer’s coverage, resulting in 62% of workers in offering firms having coverage through their employer. Among both firms that offer and do not offer health benefits, 55% of workers are covered by health plans offered by their employer, similar to 2013 (56%).

RETIREE COVERAGE

Twenty-five percent of large firms (200 or more workers) that offer health benefits in 2014 also offer retiree health benefits, similar to the percentage (28%) in 2013 but down from 35% in 2004. Among large firms (200 or more workers) that offer retiree health benefits, 92% offer health benefits to early retirees (workers retiring before age 65), 72% offer health benefits to Medicare-age retirees, and 3% offer a plan that covers only prescription drugs. There may continue to be evolution in the way that employers structure and deliver retiree benefits. Among large firms offering health benefits, 25% of firms are considering changing the way they offer retiree coverage because of the new public health insurance exchanges established by the ACA. In addition to the public exchanges, there is considerable interest in exchange options offered by private firms. Four percent of large employers currently offer their retiree benefits through a private exchange.

WELLNESS, HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENTS AND BIOMETRIC SCREENINGS

Employers continue to offer programs in large numbers that help employees identify issues with their health and engage in healthier behavior. These include offering their employees the opportunity to complete a health risk assessment, and offering a variety of wellness programs that promote healthier lifestyles, including better diet and more exercise. Some employers collect biometric information from employees (e.g., cholesterol levels and body mass index) to use as part of their wellness and health promotion programs.

Almost one-third of employers (33%) offering health benefits provide employees with an opportunity to complete a health risk assessment. A health risk assessment includes questions about medical history, health status, and lifestyle, and is designed to identify the health risks of the person being assessed. Large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely than smaller firms to ask employees to complete a health risk assessment (51% vs. 32%). Among these firms, 51% of large firms (200 or more workers) report that they provide a financial incentive to employees that complete the assessment. Thirty-six percent of firms with a financial incentive for completing a health risk assessment reported that the maximum value of the incentive is $500 or more.

Fifty-one percent of large firms (200 or more workers) and 26% of smaller firms offering health benefits report offering biometric screening to employees. A biometric screening is a health examination that measures an employee’s risk factors, such as body weight, cholesterol, blood pressure, stress, and nutrition. Of these firms, one percent of large firms require employees to complete a biometric screening to enroll in the health plan; and 8% of large firms report that employees may be financially rewarded or penalized based on meeting biometric outcomes.

Virtually all large employers (200 or more workers) and most smaller employers offer at least one wellness program. Seventy-four percent of employers offering health benefits offer at least one of the following wellness programs in 2014: 1) weight loss programs, 2) gym membership discounts or on-site exercise facilities, 3) biometric screening, 4) smoking cessation programs, 5) personal health coaching, 6) classes in nutrition or healthy living, 7) web-based resources for healthy living, 8) flu shots or vaccinations, 9) Employee Assistance Programs (EAP), or a 10) wellness newsletter. Large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely to offer one of these programs than smaller firms (98% vs. 73%). Of firms offering health benefits and a wellness program, 36% of large firms (200 or more workers) and 18% of smaller firms offer employees a financial incentive to participate in a wellness program, such as smaller premium contributions, smaller deductibles, higher HSA/HRA contributions or gift cards, travel, merchandise or cash. Among firms with an incentive to participate in wellness programs, only 12% of small firms and 33% of large firms believe that incentives are “very effective” at encouraging employees to participate. In lieu of or in addition to incentives for participating in wellness programs, 12% of large firms have an incentive for completing wellness programs.

PROVIDER NETWORKS

High Performance or Tiered Networks. Nineteen percent of employers offering health benefits have high performance or tiered networks in their largest health plan. These programs identify providers that are more efficient or have higher quality care, and may provide financial or other incentives for enrollees to use the selected providers. Employers may use different criteria to determine which providers are in which tiers. Fifty-nine percent of firms whose largest plan includes a high performance or tiered provider network stated that the network tiers were determined both by providers’ “quality and cost/efficiency”, followed by 33% who selected “cost-efficiency”.

Narrow Networks. Some employers are limiting their provider networks to reduce the cost. Six percent of employers with 50 or more employees reported that their plan eliminated hospitals to reduce cost and eight percent offer a plan considered a narrow network plan. Only six percent of employers with 50 or more workers offering health benefits stated that “narrow networks” are a very effective strategy to contain cost, less than other strategies such as “wellness program” (28%) and “consumer drive health plans” (22%).

Retail Health Clinics. Fifty-seven percent of employers offering health benefits cover services provided by retail health clinics. These may be health clinics located in grocery stores or pharmacies to treat minor illnesses or provide preventive services, such as vaccines or flu shots. Among firms covering services in these settings, eight percent provide a financial incentive to receive services in a retail clinic instead of a physician’s office.

EMPLOYEE AND DEPENDENT ELIGIBILITY

Waiting Period. The ACA limits waiting periods to no more than 90 days for non-grandfathered plans with plan years beginning after January 1, 2014. The average length of waiting periods for covered workers who face a waiting period decreased from 2.3 months in 2013 to 2.1 months in 2014. Twenty-three percent of large firms and 10% of small firms with a waiting period indicated that they decreased the length of their waiting period during the last year. As more firms renew their plans in 2014 and lose grandfathering status more firms will be subject to this provision.

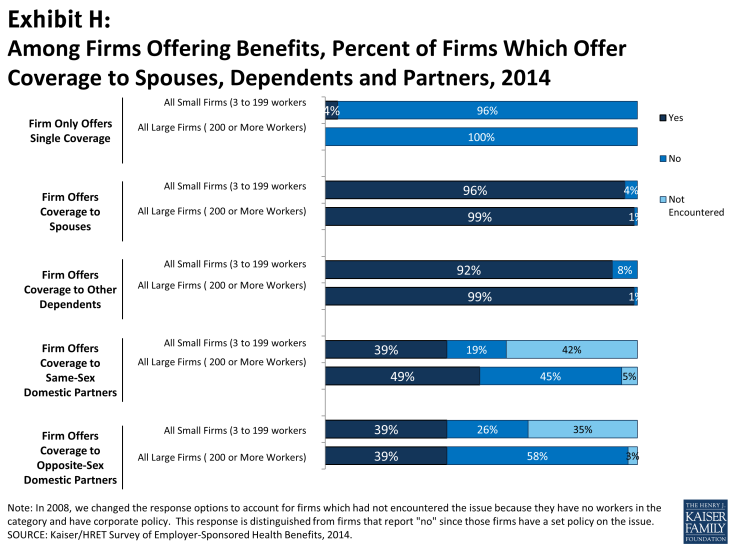

Dependent Coverage. The overwhelming majority of firms which offer coverage to at least some employees offer coverage to dependents (96%) (Exhibit H). Thirty-nine percent of firms offer coverage to same-sex domestic partners, the same percentage that offers coverage to opposite-sex domestic partners. Both percentages are similar to 2012, the last time the survey included this question. Some employers are requiring additional cost sharing (5%) or restricting eligibility for spouses (9%) to enroll if they have an offer of coverage from another source. Eighteen percent of large firms provide compensation or benefits to employees who do not enroll in coverage.

OTHER TOPICS

Grandfathered Health Plans. The ACA exempts “grandfathered” health plans from a number of its provisions, such as the requirements to cover preventive benefits without cost sharing or the new rules for small employers’ premiums ratings and benefits. An employer-sponsored health plan can be grandfathered if it covered a worker when the ACA became law (March 23, 2010) and if the plan has not made significant changes that reduce benefits or increase employee costs.3 Thirty-seven percent of firms offering health benefits offer at least one grandfathered health plan in 2014, less than 54% in 2013. Looking at enrollment, 26% of covered workers are enrolled in a grandfathered health plan in 2014, down from 36% in 2013 (Exhibit I).

Self-Funding. Fifteen percent of covered workers at small firms (3-199 workers) and 81% of covered workers at larger firms are enrolled in plans which are either partially or completely self-funded. The percent of covered workers enrolled in self-funded plans has increased for large firms since 2004, but has remained stable for both large and small firms over the last couple of years.

Private Exchanges for Large Employers. While relatively few covered workers at large employers currently receive benefits through a private or corporate health insurance exchange (3%), many firms are looking at this option. Private exchanges allow employees to choose from several health benefits options offered on the exchange. A private exchange is created by a consulting company or insurer, rather than a governmental entity. Thirteen percent of large firms are considering offering benefits through a private exchange and 23% are considering using a defined contribution method. This interest may signal a significant change in the way that employers approach health benefits and the way employees get coverage.

CONCLUSION

The 2014 survey found considerable stability among employer-sponsored plans. Similar percentages of employers offered benefits to at least some employees and a similar percentage of workers at those firms were covered by benefits compared to last year. Family premiums increased at a modest rate and single premiums are not statistically different than those reported last year. On average, covered workers contribute the same percentage of the premium for single and family coverage as they did last year.

The relatively quiet period in 2014 may give way to bigger changes in 2015 as the employer shared-responsibility provision in the ACA takes effect for large employers. This provision requires firms with more than 100 full time equivalent employees (FTEs) in 2015 and more than 50 FTEs in 2016 to provide coverage to their full-time workers or possibly pay a penalty if workers seek subsidized coverage in health care exchanges. While most large employers provide coverage to workers, not all do, and not all cover all of their full-time workers. In addition, the coverage offered by these larger employers must meet a certain value and must be offered at an affordable amount to workers. We expect some employers to revise eligibility and contributions for benefits in response to the new provisions.

The continued implementation of major reforms in the non-group market also may affect employer strategies going forward. For smaller firms not subject to the employer-responsibility requirement, the ability of their employees to receive subsidized nongroup coverage in health insurance exchanges may be an attractive alternative which would relieve the employer of the burden of sponsoring coverage. Small firms that have struggled to offer good coverage options may decide to stop offering now that other alternatives are available. In addition, a quarter of large firms offering retiree coverage to active workers indicated they were considering changes to the way they offered retiree coverage because of the implementation of the public exchanges. We may see shifts in the coverage options offered by some employers in response to these new options and new tax incentives.

Employer-sponsored coverage also will continue to evolve for reasons that are not related to the ACA. Employers and insurers continue to develop more integrated approaches to assessing individuals’ personal health risks and offering programs to address them. Wellness programs present enrollees with opportunities and challenges, including the possibility of much higher out-of-pocket costs if their health profile is a potentially costly one. Narrow networks and provider networks and new tools like reference pricing can lower premiums but also require enrollees to have a more active role in ensuring that they have access to the providers they want to use. And the development of private marketplaces for larger employers, if it continues, may signal a new direction where individual employers are less engaged in plan design and management and where more decisions and economic responsibility is shifted to employees.

Finally, the continuing improvement in the economy is likely to put new cost pressure on employers and insurers. Costs grew at low levels while the economy struggled, but are likely to rebound if the growth in the economy is sustained. The potential of higher premiums may push employers and insurers to accelerate some of the changes we already are seeing.

METHODOLOGY

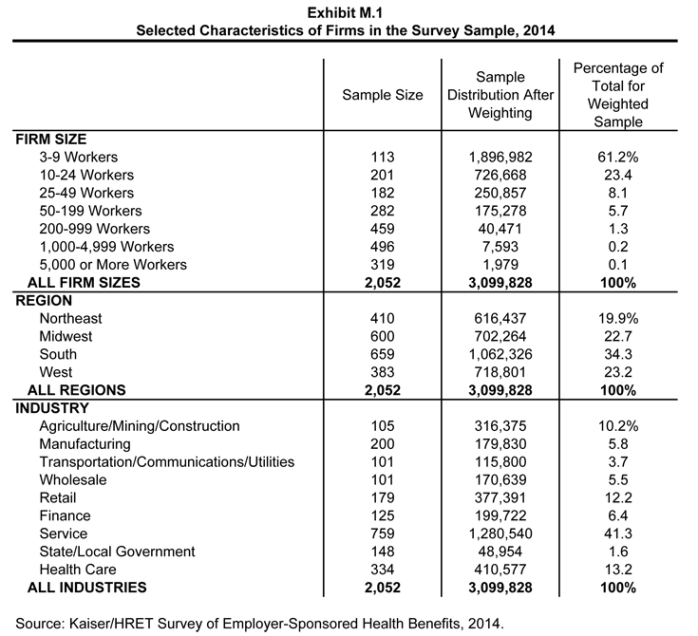

The Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research & Educational Trust 2014 Annual Employer Health Benefits Survey (Kaiser/HRET) reports findings from a telephone survey of 2,052 randomly selected public and private employers with three or more workers. Researchers at the Health Research & Educational Trust, NORC at the University of Chicago, and the Kaiser Family Foundation designed and analyzed the survey. National Research, LLC conducted the fieldwork between January and May 2014. In 2014 the overall response rate is 46%, which includes firms that offer and do not offer health benefits. Among firms that offer health benefits, the survey’s response rate is also 46%.

We ask all firms with which we made phone contact, even if the firm declined to participate in the survey: “Does your company offer a health insurance program as a benefit to any of your employees?” A total of 3,139 firms responded to this question (including the 2,052 who responded to the full survey and 1,087 who responded to this one question). Their responses are included in our estimates of the percentage of firms offering health coverage. The response rate for this question is 70%.

Since firms are selected randomly, it is possible to extrapolate from the sample to national, regional, industry, and firm size estimates using statistical weights. In calculating weights, we first determine the basic weight, then apply a nonresponse adjustment, and finally apply a post-stratification adjustment. We use the U.S. Census Bureau’s Statistics of U.S. Businesses as the basis for the stratification and the post-stratification adjustment for firms in the private sector, and we use the Census of Governments as the basis for post-stratification for firms in the public sector. Some numbers in the exhibits in the report do not sum up to totals due to rounding effects, and, in a few cases, numbers from distribution exhibits referenced in the text may not add due to rounding effects. Unless otherwise noted, differences referred to in the text and exhibits use the 0.05 confidence level as the threshold for significance. In 2014 we adjusted the premiums for a small number of firms which gave a composite family/single amount.

For more information on the survey methodology, please visit the Survey Design and Methods Section at http://ehbs.kff.org/.

The Kaiser Family Foundation, a leader in health policy analysis, health journalism and communication, is dedicated to filling the need for trusted, independent information on the major health issues facing our nation and its people. The Foundation is a non-profit private operating foundation, based in Menlo Park, California.

The Health Research & Educational Trust is a private, not-for-profit organization involved in research, education, and demonstration programs addressing health management and policy issues. Founded in 1944, HRET, an affiliate of the American Hospital Association, collaborates with health care, government, academic, business, and community organizations across the United States to conduct research and disseminate findings that help shape the future of health care.

Report

Section One: Cost of Health Insurance

The average annual premiums in 2014 are $6,025 for single coverage and $16,834 for family coverage. The average family premium increased 3% in the last year; the average single premium, however, is similar to the value reported in 2013 ($5,884). Family premiums have increased 69% since 2004 and have more than doubled since 2002. However, the average family premium has grown less quickly over the last five years than it did between 2004 and 2009 or between 1999 and 2004. Average family premiums for workers in small firms (3-199 workers) ($15,849) are significantly lower than average family premiums for workers in larger firms (200 or more workers) ($17,265).

Premium Costs for Single and Family Coverage

- The average premium for single coverage in 2014 is $502 per month, or $6,025 per year (Exhibit 1.1). The average premium for family coverage is $1,403 per month or $16,834 per year (Exhibit 1.1).

- The average annual premiums for covered workers in HDHP/SOs are lower for single ($5,299) and family coverage ($15,401) than the overall average premiums for covered workers. Average annual premiums for all other plan types, including PPOs, HMOs, and POS plans, are similar to the overall average premiums for covered workers (Exhibit 1.1).

- The average annual premium for family coverage for covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) ($15,849) is lower than the average premium for covered workers in large firms (200 or more workers) ($17,265) (Exhibit 1.2). The average annual single premium for covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) also is significantly lower than for workers in larger firms ($5,788 vs. $6,130).

- Average single and family premiums for covered workers are higher in the Northeast ($6,369 and $17,772) and lower in the South ($5,720 and $16,170) than the average premiums for covered workers in all other regions (Exhibit 1.3).

- Average single and family premiums for covered workers in the Wholesale ($5,189 and $15,599) and Retail ($5,355 and $14,979) industries are lower than the average premiums for covered workers in all other industries (Exhibit 1.4).

- Covered workers in firms where 35% or more of the workers are age 26 or younger have lower average single and family premiums ($5,292 and $15,182) than covered workers in firms where a lower percentage of workers are age 26 or younger ($6,079 and $16,955). Covered workers in firms where 35% or more of the workers are age 50 or older have higher average single and family premiums ($6,313 and $17,425) than covered workers in firms where a lower percentage of workers are age 50 or older ($5,759 and $16,286) (Exhibit 1.5) and (Exhibit 1.6).

- Covered workers in firms with a large percentage of lower-wage workers (at least 35% of workers earn $23,000 per year or less) have lower average single and family premiums ($5,175 and $14,177) than covered workers in firms with a smaller percentage of lower-wage workers ($6,093 and $17,044). Covered worker in firms with a large percentage of higher-wage workers (at least 35% of workers earn $57,000 per year or more) have higher average single and family premiums ($6,244 and $17,582) than covered workers in firms with a smaller percentage of higher-wage workers ($5,819 and $16,124) (Exhibit 1.5) and (Exhibit 1.6).

- There is considerable variation in premiums for both single and family coverage.

- Twenty percent of covered workers are employed by firms that have a single premium at least 20% higher than the average single premium, while 21% of covered workers are in firms that have a single premium less than 80% of the average single premium (Exhibit 1.7) and (Exhibit 1.8).

- For family coverage, 20% of covered workers are employed in a firm that has a family premium at least 20% higher than the average family premium, and another 20% of covered workers are in firms that have a family premium less than 80% of the average family premium (Exhibit 1.7) and (Exhibit 1.8).

Premium Changes Over Time

- The average premiums for covered workers in2014 are $6,025 annually, or $502 per month, for single coverage and $16,834 annually, or $1,403 per month, for family coverage. The 2014 average single premium is similar to the 2013 average premium (the 2 percent increase is not significant). However, the 2014 average family premium is 3 percent higher than the 2013 average premium (Exhibit 1.11).

- The $16,834 average annual family premium in 2014 is 26% higher than the average family premium in 2009 and 69% higher than the average family premium in 2004 (Exhibit 1.11). The 26% premium growth seen in the last five years (2009 to 2014) is significantly lower than the 34% premium growth seen in the previous five year period, from 2004 to 2009 (Exhibit 1.16).

- Premiums for both small and large firms have seen a similar increase since 2009 (25% for small and 26% for large). For small firms (3 to 199 workers), the average family premium rose from $12,696 in 2009 to $15,849 in 2014. For large firms (200 or more workers), the average family premium rose from $13,704 in 2009 to $17,265 in 2014 (Exhibit 1.13).

- Since 2004, premiums for small firms (3 to 199 workers) have increased 63% ($15,849 in 2014 vs. $9,737 in 2004). The premiums for large firms have increased 72% ($17,265 in 2014 vs. $10,046 in 2004) (Exhibit 1.13).

- Average family premiums for firms with fewer low-wage workers (less than 35% of workers earn $23,000 per year or less) grew in the last year ($17,044 vs. $16,450), while premiums for family coverage for firms with many low-wage workers were similar to 2013 ($14,177 vs. $15,225) (Exhibit 1.15). Overall, premiums for family coverage have grown faster for firms with fewer low-wage workers than firms with many low-wage workers over the last year (4% vs. -7%), as well as the last five years (27% vs. 9%). A similar pattern is observed for single coverage, where average premiums have grown faster for firms with fewer lower-wage workers than firms with many lower wage workers over the last five years (26% vs. 12%).

- For large firms (200 or more workers), the average family premium for covered workers in firms that are fully insured has grown at a similar rate to premiums for workers in fully or partially self-funded firms from 2009 to 2014 (26% in both fully insured and self-funded firms) and from 2004 to 2014 (71% in fully insured firms vs. 73% in self-funded firms) (Exhibit 1.17).

Section Two: Health Benefits Offer Rates

While nearly all large firms (200 or more workers) offer health benefits to at least some employees, small firms (3-199 workers) are significantly less likely to do so. The percentage of all firms offering health benefits in 2014 (55%) is not statistically different from 2013 and 2012 (57% and 61%, respectively). Over a third of firms offering health benefits cover (39%) same-sex domestic partners; the same percentage which covers opposite-sex domestic partners. Nine percent of firms which offer family coverage restrict eligibility to a spouse when he/she has another offer of coverage. Among large employers offering health benefits 88% offer or contribute to separate dental benefits and 63% do so for separate vision benefits. Firms not offering health benefits continue to cite “cost” as the most important reason they do not offer health benefits (32%).

- Offer rates vary across different types of firms.

- Smaller firms are less likely to offer health insurance: 44% of firms with 3 to 9 workers offer coverage, compared to 64% of firms with 10 to 24 workers, 83% of firms with 25 to 49 workers, and 91% of firms with 50 to 199 employees (Exhibit 2.3).

- Offer rates throughout different firm size categories in 2014 remained similar to those reported in 2013 (Exhibit 2.2).

- Firms with fewer lower-wage workers (less than 35% of workers earn $23,000 or less annually) are significantly more likely to offer health insurance than firms with many lower-wage workers (55% vs. 33%) (Exhibit 2.4). The offer rate for firms with many lower-wage workers is not significantly different from the 23% reported in 2013.

- We observe a similar pattern among firms with many higher-wage workers (35% or more of workers earn $57,000 or more annually) being more likely to offer coverage to employees (69% versus 47%) (Exhibit 2.4).

- The age of the workforce correlates with the probability of a firm offering health benefits. Firms where 35% or more of its workers are age 26 or younger are less likely to offer health benefits than firms where less than 35% of workers are age 26 or younger (30% and 53%, respectively) (Exhibit 2.4). The percentage of firms with many younger workers that offer health benefits is similar to the 23% reported in 2013.

- In 2014, 55% of firms offer health benefits not statistically different from the 57% reported in 2013 (Exhibit 2.1).1

- Ninety-eight percent of large firms (200 or more workers) offer health benefits to at least some of their workers (Exhibit 2.3). In contrast, only 54% of small firms (3-199 workers) offer health benefits in 2014. The percentage of both small and large firms offering health benefits to at least some of their workers is similar to last year (Exhibit 2.2).

- Between 1999 and 2014, the offer rate for large firms (200 or more workers) has consistently remained at or above 97%.

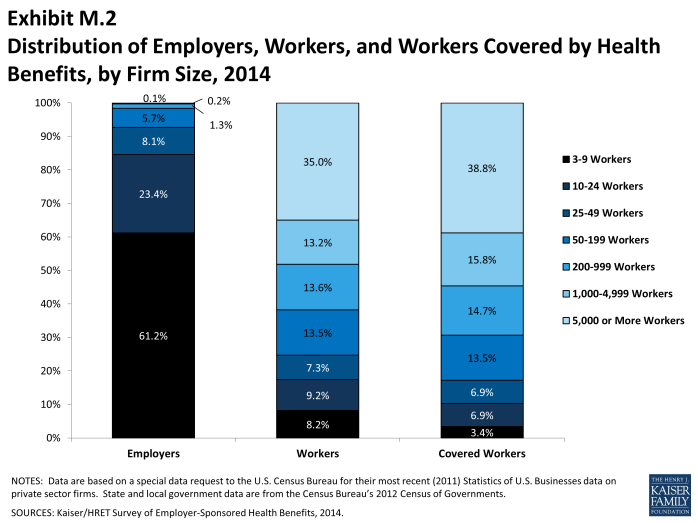

- Since most firms in the country are small, variation in the overall offer rate is driven primarily by changes in the percentages of the smallest firms (3-9 workers) offering health benefits. For more information on the distribution of firms in the country, see the Survey Design and Methods Section and Exhibit M1.

- As the “employer shared responsibility” provision takes effect in 2015, some employers may adjust their workforce’s employment status to mitigate the provision’s impact. Starting in 2015, employers with more than 100 full time equivalents2 who do not offer their full-time employees coverage will pay a penalty if one of their employees receives a premium subsidy on a health insurance exchange. Employers will be charged a penalty of $2,000 for each employee beyond their first 30 employees if they do not offer coverage. For example, a firm with 65 employees would be charged $70,000 annually for not offering coverage (35 employees multiplied by $2,000 per employee). Employers that offer coverage may still be assessed a penalty if the coverage is either too expensive or does not meet minimum standards. Coverage offered by an employer must pay for 60% of a population’s covered medical expenses. In addition, the worker contribution to the premium cannot exceed 9.5% of the household’s income.

- Ninety-four percent of firms with 100 or more employees offered health benefits to at least some of their employees in 2014. Ninety percent of firms with between 50 and 99 workers offered benefits to at least some workers. Since the survey does not ask employers how many full-time equivalents they have, these firm size categories are determined by the number of workers at a firm and may include both full-time and part-time employees.

Part-Time and Temporary Workers

- Among firms offering health benefits, relatively few offer benefits to their part-time and temporary workers.

- In 2014, 24% of all firms that offer health benefits offer them to part-time workers, similar to the 25% reported in 2013 (Exhibit 2.5). Firms with 200 or more workers are more likely to offer health benefits to part-time employees than firms with 3 to 199 workers (46% vs. 24%) (Exhibit 2.7).

- A small percentage (5% in 2014) of firms offering health benefits have offered them to temporary workers (Exhibit 2.6). The percentage of firms offering temporary workers benefits are similar for small firms (3-199 workers) and larger firms (5% vs. 9%) (Exhibit 2.8). The percentage of firms offering health benefits to temporary workers has remained stable over time.

Dental and Vision Benefits

- Fifty-three percent of firms offering health benefits offer or contribute to a dental insurance benefit for their employees that is separate from any dental coverage the health plans might include. This is not statistically different from the 54% reported in 2012, which is the last time the survey asked about dental benefits (Exhibit 2.10). Large firms (200 or more workers) are far more likely than smaller firms to offer or contribute to a separate dental health benefit (88% vs. 52%) (Exhibit 2.9).

- Thirty-five percent of firms offer or contribute to a vision benefit for their employees that is separate from any vision coverage the health plan might include, which is not statistically different than the 27% we reported in 2012 but higher than 17% in 2010 (Exhibit 2.10).

- Large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely than smaller firms to offer or contribute to a separate vision care benefit, at 63% versus 34% (Exhibit 2.9).

Spouses, Dependents and Domestic Partner Benefits

The vast majority of firms offering health benefits offer benefits to spouses and dependents, such as children.

- In 2014, 96% of small firms (3 to 199 workers) and 99% of larger firms offering health benefits offer coverage to spouses. Similarly, in 2014, 92% of small firms and 99% of large firms offering health benefits cover other dependents, such as children. Four percent of small firms offering health benefits do not offer coverage to any dependents (Exhibit 2.11).

- This year we asked employers whether same-sex and opposite-sex domestic partners were allowed to enrolled in a firm’s coverage. While definitions may vary, employers often define domestic partners as an unmarried couple who have lived together for a specified period of time. Firms may define domestic partners separate from any legal requirements a state may have. Employers may have a different policy in different parts of the country.

- In 2014, 39% of firms offering health benefits offered coverage to unmarried opposite-sex partners, similar to the 37% who did so in 2012, the last time this question was asked). In 2014, 39% of firms offering benefits covered same-sex domestic partners, unchanged from the 31% in 2012 (Exhibit 2.13).

- The rates at which firms have offered domestic partner benefits have increased over a longer period of time. For example, in 2014, 39% of firms offered benefits to same-sex domestic partners, a significant increase from the 22% that did so in 2008. The percentage of offering firms which covered opposite-sex domestic partner benefits has also increased from 24% in 2008 to 39% in 2014.

- When we ask employers if they offer health benefits to opposite or same-sex domestic partners, many firms report that they have not encountered the issue of whether benefits would be offered to domestic partners. At many small firms (3-199 Workers), the firm may not have formal HR policies on domestic partners simply because none of the firm’s employees have asked to cover a domestic partner. Regarding health benefits for opposite-sex domestic partners, 34% of firms report in 2014 that they have not encountered this need or that the question was not applicable. The vast majority of firms in the United States are small business; 61% of firms have between 3 and 9 employees and 98% have between 3 and 199 employees. Therefore statistics about the percentage of firms that offer domestic partner benefits is largely controlled by small businesses. More small firms (35%) compared to large firms (3%) indicate that they have not encountered this need or that the question was not applicable (Exhibit 2.12). Regarding health benefits for same-sex domestic partners, 41% of firms report that they have not encountered the need or that the question was not applicable. More small firms (3–199 workers) (42%) than larger firms (5%) report that they have not encountered the issue of offering benefits to same-sex domestic partners (Exhibit 2.12).

- Firms in the Northeast are more likely (60%) and firms in the South are less likely (25%) to offer health benefits to unmarried same-sex domestic partners than firms in other regions (Exhibit 2.12). Firms in the Northeast are more likely (50%) to offer health benefits to unmarried opposite-sex domestic partners than firms in other regions (Exhibit 2.12).

- Firms in the state and local government industry are less likely to offer either same sex or opposite sex domestic partner benefits than firms in other industries (Exhibit 2.12).

- Firms may adjust their eligibility for some dependents based on whether the dependent has another offer of coverage.

- Among firms offering coverage to spouses, spouses are not eligible to enroll for coverage if they are offered health insurance from another source at nine percent of firms (Exhibit 2.14).

- Five percent of firms offering coverage to spouses require a greater contribution for coverage if a spouse is offered health insurance from another source. Large employers (200 or more workers) are more likely than small employer to have this requirement (9% vs. 5%) (Exhibit 2.14).

Firms Not Offering Health Benefits

- The survey asks firms that do not offer health benefits if they have offered insurance or shopped for insurance in the recent past, and about their most important reasons for not offering coverage. Because such a small percentage of large firms report not offering health benefits, we present responses for smaller firms (3 to 199 workers) that do not offer health benefits.

- The cost of health insurance remains the primary reason cited by firms for not offering health benefits. Among small firms (3-199 workers) not offering health benefits, 32% cite high cost as “the most important reason” for not doing so, followed by “employees are generally covered under another plan” (24%) (Exhibit 2.15). This year we asked employers whether the launch of the health insurance exchanges for individuals was the primary reason for not offering benefits; nine percent of employers cited “employees have other options, including exchanges” and one percent said “employees will get a better deal on the health insurance exchanges” (Exhibit 2.15). More small firms indicated they did not offer because of “cost” and “employees are generally covered under another plan” than “employees have other options, including exchanges”.

- Many non-offering, small firms have either offered health benefits in the past five years, or shopped for alternative coverage options recently.

- Eighteen percent of non-offering, small firms (3-199 workers) have offered health benefits in the past five years, while 24% have shopped for coverage in the past year (Exhibit 2.16). The 24% of non-offering small firms which have shopped for coverage in the past year is similar to the 18% who did so last year.

- Among non-offering, small firms (3-199 workers), 7% report that they provide funds to their employees to purchase health insurance through the individual, or non-group, market, such as on an individual health insurance marketplace (Exhibit 2.17). The percentage of firms offering funds to purchase non-group coverage is similar to last year (10%).

- Three-quarters of small firms (3-199 employees) not offering health benefits believed that their employees would prefer a two dollar per hour increase in wages rather than health insurance (Exhibit 2.18). The percentage of small employers who believe that their employees would prefer a wage increase is the same as 2011 the last time the survey asked this question (75%).

- Small firms (3-199 workers) not offering health insurance gave a variety of estimates regarding the amount they believe the firm could afford to pay for health insurance for an employee with single coverage. Thirty-nine percent reported that they could pay less than $100 per month; 6% reported that they could pay $400 or more per month (Exhibit 2.19).

- Small firms (3-199 workers) not offering health benefits were asked to estimate what percentage of their employees had coverage from another source. Fifty percent of small employers estimated that three quarters or more of their employees were covered (Exhibit 2.20). On average, non-offering firms with between 3-9 employees believed that 75% of their employees had another source of coverage, 58% at firms with 10 to 24 employees, and 44% at firms with 25 to 199 employees.

SHOP Exchanges

Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) are federal or state sponsored exchanges in which employers may offer and contribute to health insurance provided to their employees. In many states SHOP exchanges were not fully implemented and many employers experience technical difficulties when trying to enroll. Small employers may qualify for the small business health care tax credit when purchase coverage through the SHOP exchanges. In 2014, firms with 50 or fewer full-time equivalents are eligible to participate in a SHOP exchange.

- Because our survey gathers information about the total number of full-time and part-time employees in a firm, we cannot calculate the number of full-time equivalent employees and therefore could not limit survey responses only to firms within the size range eligible for the SHOP marketplaces. To ensure that we included employers that may have a number of part-time or temporary employees but could still qualify, we directed questions to employers with 3 to 75 total employees. This approach allowed us to capture some employers with more than 50 employees who would nonetheless be eligible, but it also means that that some employers who are unlikely to be eligible were asked these questions.

- Thirteen percent of firms with 3 to 75 employees who do not offer health benefits said they looked at purchasing coverage on a SHOP exchange. Similarly, twelve percent of firms with 3 to 75 employees that do offer health benefits looked at coverage on the SHOP exchanges (Exhibit 2.21).

- Among non-offering firms with 3 to 75 employees that chose not to purchase coverage on a SHOP exchange, 40% reported they did not do so because they were not interested and 28% said it was too expensive (Exhibit 2.22).

Section Three: Employee Coverage, Eligibility, and Participation

Employers are the principal source of health insurance in the United States, providing health benefits for about 149 million non-elderly people in America.1 Most workers are offered health coverage at work, and the majority of workers who are offered coverage take it. Workers may not be covered by their own employer for several reasons: their employer may not offer coverage, they may be ineligible for benefits offered by their firm, they may elect to receive coverage through their spouse’s employer, or they may refuse coverage from their firm. In 2015, new coverage requirements will be implemented that may affect employers’ decisions about offering health care coverage going forward.

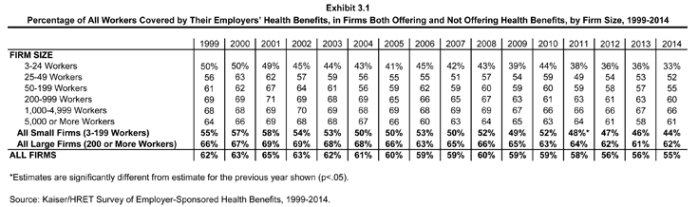

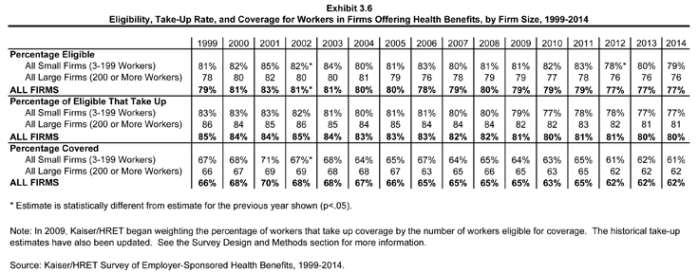

- Among firms offering health benefits, 62% percent of workers are covered by health benefits through their own employer (Exhibit 3.2).

- When considering both firms that offer health benefits and those that don’t, 55% of workers are covered under their employer’s plan (Exhibit 3.1). This coverage rate has slowly decreased over time, down from 59% in 2009 and 61% in 2004.

Eligibility

- Not all employees are eligible for the health benefits offered by their firm, and not all eligible employees “take up” (i.e., elect to participate in) the offer of coverage. The share of workers covered in a firm is a product of both the percentage of workers who are eligible for the firm’s health insurance and the percentage who choose to take up the benefit.

- Seventy-seven percent of workers in firms offering health benefits are eligible for the coverage offered by their employer (Exhibit 3.2).

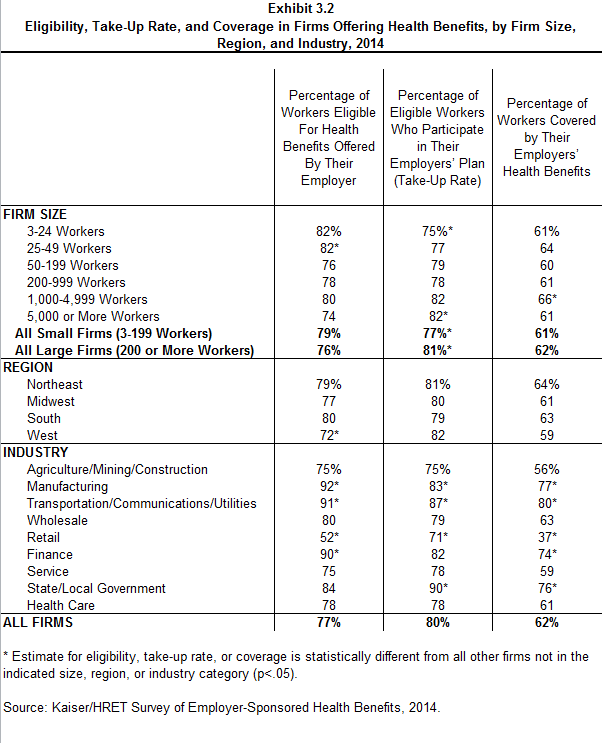

- Eligibility varies considerably by wage level. Employees in firms with a lower proportion of lower-wage workers (less than 35% of workers earn $23,000 or less annually) are more likely to be eligible for health benefits than employees in firms with a higher proportion of lower-wage workers (79% vs. 63%). We observe a similar pattern among firms with many higher-wage workers (35% or more of workers earn $57,000 or more annually) (83% vs. 73%) (Exhibit 3.3).

- Eligibility also varies by the age of the workforce. Those in firms with fewer younger workers (less than 35% of workers are age 26 or younger) are more likely to be eligible for health benefits than those in firms with many younger workers, at 79% versus 59% (Exhibit 3.3).

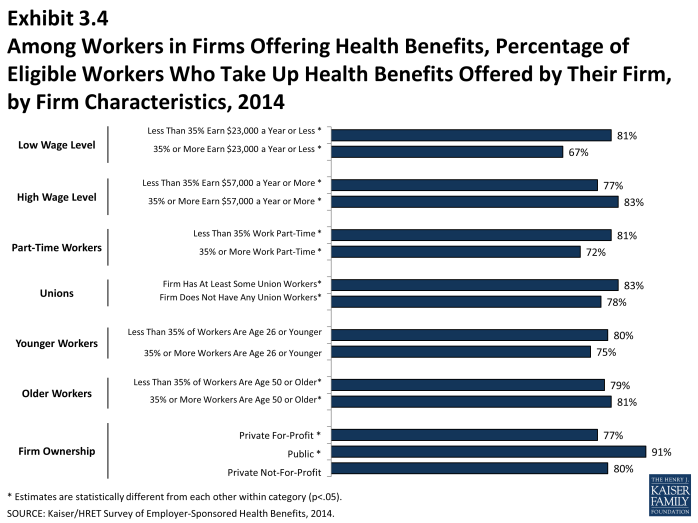

Take-up Rate

- Employees who are offered health benefits generally elect to take up the coverage. In 2014, 80% of eligible workers take up coverage when it was offered to them, the same rate as last year (Exhibit 3.2).2

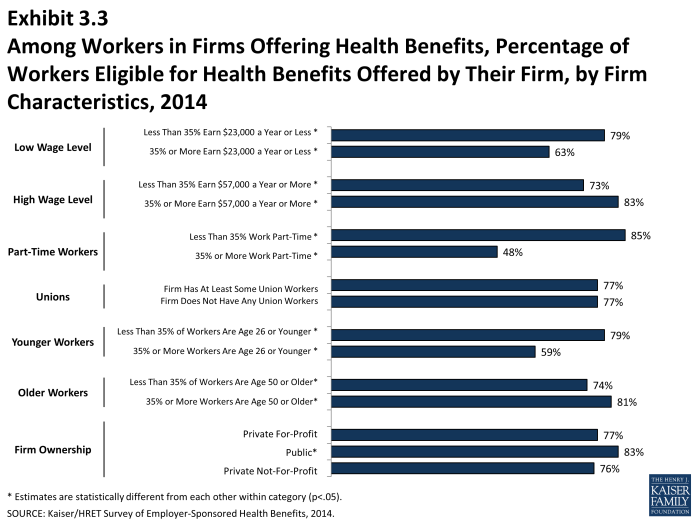

- The likelihood of a worker accepting a firm’s offer of coverage also varies with the workforces’ wage level. Eligible employees in firms with a lower proportion of lower-wage workers are more likely to take up coverage (81%) than eligible employees in firms with a higher proportion of lower-wage workers (35% or more of workers earn $23,000 or less annually) (67%) (Exhibit 3.4). Similar patterns are seen in firms with a larger proportion of higher-wage workers, with workers in these firms being more likely to take up coverage than those in firms with a smaller share of higher wage workers (83% vs. 77%).

- Ninety-one percent of workers at public employers who offer health benefits take up coverage. Workers at private-for-profit employers are significantly less likely to do so – only 77% of these workers take up coverage (Exhibit 3.4).

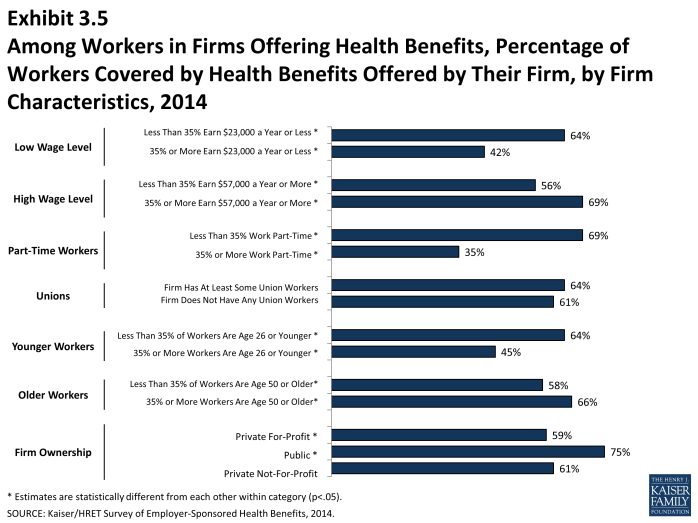

Coverage

- There is significant variation by industry in the coverage rate among workers in firms offering health benefits. For example, only 37% of workers in retail firms offering health benefits are covered by the health benefits offered by their firm, compared to 74% of workers in finance, and 80% of workers in the transportation/communications/utilities industry category (Exhibit 3.2).

- Among workers in firms offering health benefits, those in firms with relatively few part-time workers (less than 35% of workers are part-time) are much more likely to be covered by their own firm than workers in firms with a greater percentage of part-time workers (69% vs. 35%) (Exhibit 3.5).

- Among workers in firms offering health benefits, those in firms with fewer lower-wage workers (less than 35% of workers earn $23,000 or less annually) are more likely to be covered by their own firm than workers in firms with many lower-wage workers (64% vs. 42%) (Exhibit 3.5). A comparable pattern exists in firms with a larger proportion of higher wage workers (35% or more earn $57,000 or more annually) offering health benefits (69% vs. 56%).

- Among workers in firms offering health benefits, those in firms with fewer younger workers (less than 35% of workers are age 26 or younger) are more likely to be covered by their own firm than those in firms with many younger workers (64% vs. 45%) (Exhibit 3.5).

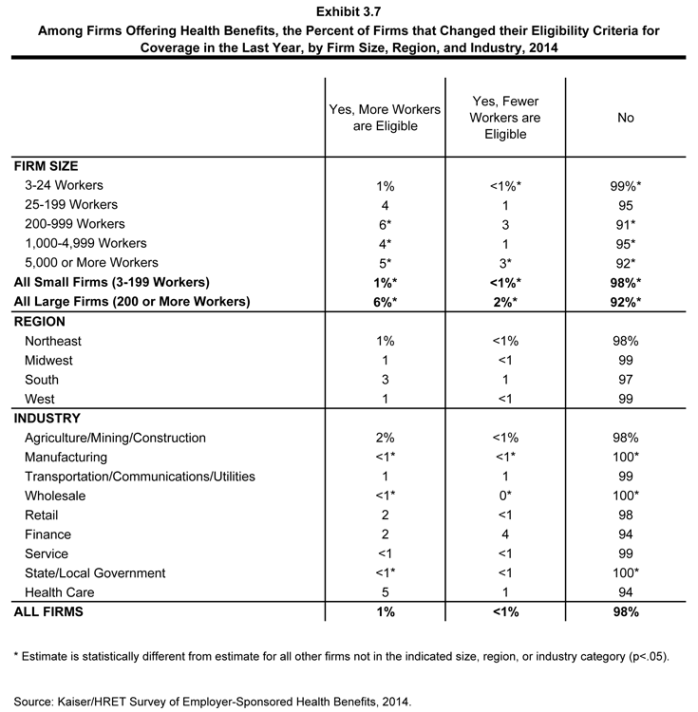

- Ninety-eight percent of firms offering health benefits reported that they did not change eligibility criteria by either increasing or decreasing the share of workers eligible for health benefits in the last year (Exhibit 3.7).

Waiting Periods

- Waiting periods are a specified length of time after beginning employment before employees are eligible to enroll in health benefits. The ACA requires that waiting periods cannot exceed 90 days for non-grandfathered plans for plan years that begin on or after January 1, 2014. This survey is conducted from January to May annually, at which time many firms report information on their current plans. In some cases those plan years may have started in the previous calendar year (in this case, 2013). Some employers may have renewed their plan year in 2013 in order to delay implementing provisions of the ACA slated to take effect on January 1 2014. Also, many covered workers are enrolled in grandfathered health which are exempt from certain provisions of the ACA including the requirement to have a waiting period of less than 90 days (for more information see Section 13). If an employee is eligible to enroll on the 1st of the month, after two months this survey “rounds-up” and say the firm’s waiting period is three months. For these reasons some employers still have waiting periods exceed the 90 day maximum.

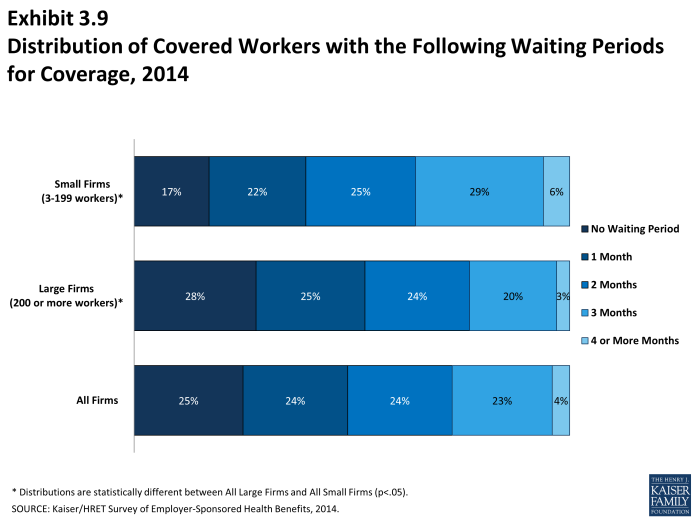

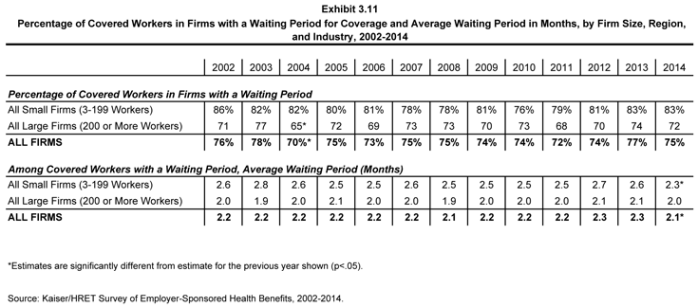

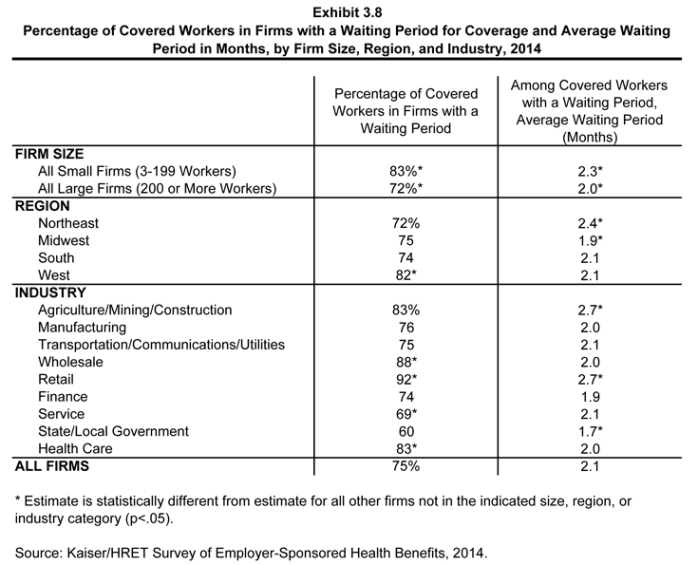

- Seventy-five percent of covered workers face a waiting period before coverage is available. Covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) are more likely than those in large firms to have a waiting period, at 83% versus 72% (Exhibit 3.8). Workers in the West are more likely to face a wait for coverage than all other regions (82%).

- The average waiting period among covered workers who face a waiting period is 2.1 months (Exhibit 3.8). While 27% of covered workers face a waiting period of 3 months or more, only 4% face a waiting period of 4 months or more. Workers in small firms (3-199 workers) generally have longer waiting periods than workers in larger firms (Exhibit 3.9).

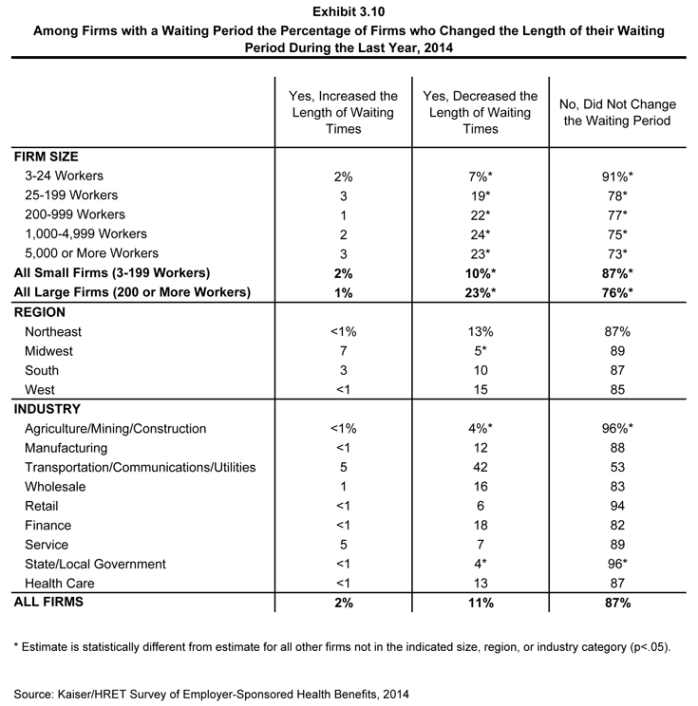

- In 2014, 11% of firms offering health benefits reported that they reduced the duration of the waiting period, significantly higher than the 2% that increased it (Exhibit 3.10).

- Ninety-one percent of covered workers at firms with many lower-wage workers (firms where 35% or more of the workforce makes $23,000 or less) face a waiting period before coverage is available compared to 76% at firms with few lower-wage workers.

- The percentage of covered workers who face a waiting period is similar to last year. The average length of the waiting period for covered workers who face a waiting period decreased, however, from 2.3 months to 2.1 months (Exhibit 3.11).

Section Three: Employee Coverage, Eligibility, and Participation

exhibits

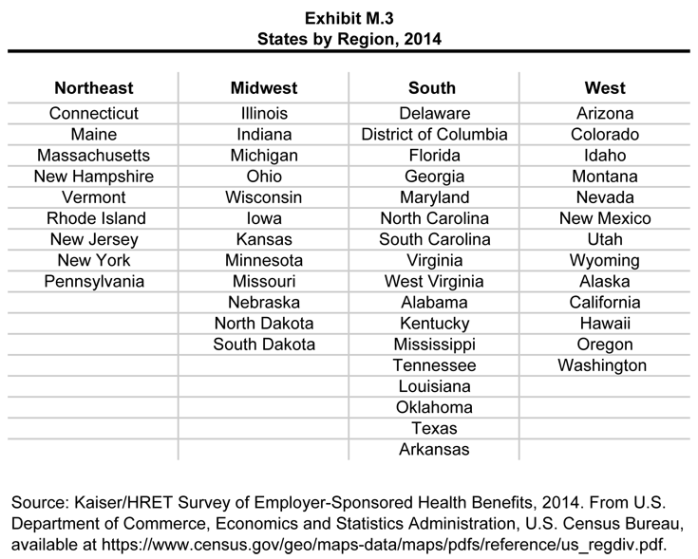

Percentage of All Workers Covered by Their Employers’ Health Benefits, in Firms Both Offering and Not Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 1999-2014

Eligibility, Take-Up Rate, and Coverage in Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, Region, and Industry, 2014

Among Workers in Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Workers Eligible for Health Benefits Offered by Their Firm, by Firm Characteristics, 2014

Among Workers in Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Eligible Workers Who Take Up Health Benefits Offered by Their Firm, by Firm Characteristics, 2014

Among Workers in Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Workers Covered by Health Benefits Offered by Their Firm, by Firm Characteristics, 2014

Eligibility, Take-Up Rate, and Coverage for Workers in Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 1999-2014

Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, the Percent of Firms that Changed their Eligibility Criteria for Coverage in the Last Year, by Firm Size, Region, and Industry, 2014

Percentage of Covered Workers in Firms with a Waiting Period for Coverage and Average Waiting Period in Months, by Firm Size, Region, and Industry, 2014

Section Four: Types of Plans Offered

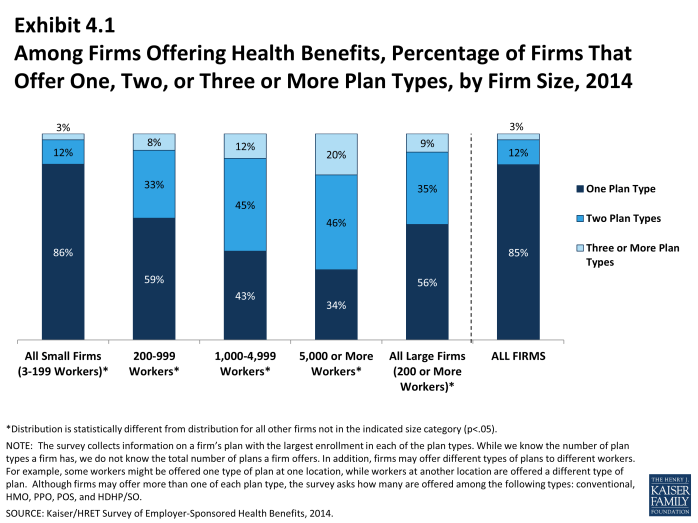

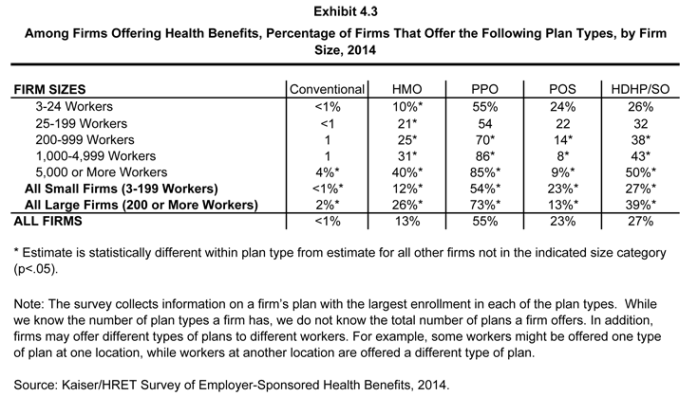

Most firms that offer health benefits offer only one type of health plan (85%) (See Text Box). Large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely to offer more than one type of health plan than smaller firms. Employers are most likely to offer their workers a PPO or HDHP/SO plan and are least likely to offer a conventional plan (sometimes known as indemnity insurance).

- Eighty-five percent of firms offering health benefits in 2014 offer only one type of health plan. Large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely to offer more than one plan type than small firms (3-199 workers): 44% vs. 14% (Exhibit 4.1).

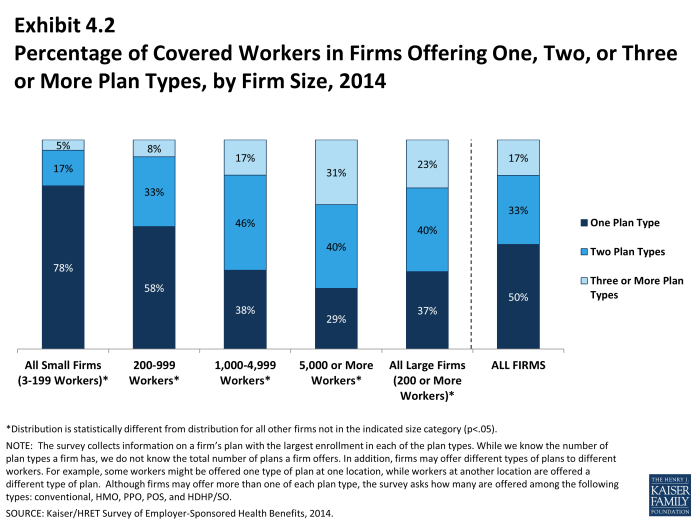

- In addition to looking at the percentage of firms which offer multiple plan types, the percent of covered workers at firms which offer multiple plan types can be analyzed. Half (50%) of covered workers are employed in a firm that offers more than one health plan type. Sixty-three percent of covered workers in large firms (200 or more workers) are employed by a firm that offers more than one plan type, compared to 22% in small firms (3-199 workers) (Exhibit 4.2).

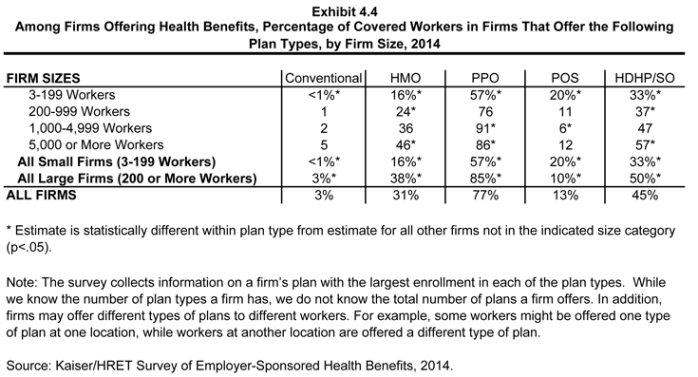

- Three quarters (77%) of covered workers in firms offering health benefits work in a firm that offers one or more PPO plans; 45% work in firms that offer one or more HDHP/SOs; 31% work in firms that offer one or more HMO plans; 13% work in firms that offer one or more POS plans; and 3% work in firms that offer one or more conventional plans (Exhibit 4.4).1

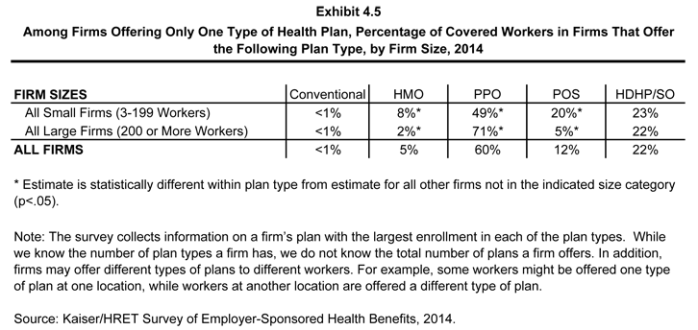

- Among firms offering only one type of health plan, large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely to offer PPO plans than small firms (3-199 workers) (71% versus 49%), while small firms are more likely to offer HMO (8%) and POS (20%) plans than larger firms (2% and 5%, respectively) (Exhibit 4.5).

- Eleven percent of covered workers are covered at firm which only offers an HDHP/SO.

The survey collects information on a firm’s plan with the largest enrollment in each of the plan types. While we know the number of plan types a firm has, we do not know the total number of plans a firm offers. In addition, firms may offer different types of plans to different workers. For example, some workers might be offered one type of plan at one location, while workers at another location are offered a different type of plan.

HMO is health maintenance organization.

PPO is preferred provider organization.

POS is point-of-service plan.

HDHP/SO is high-deductible health plan with a savings option such as an HRA or HSA.

Section Four: Types of Plans Offered

exhibits

Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Firms That Offer One, Two, or Three or More Plan Types, by Firm Size, 2014

Percentage of Covered Workers in Firms Offering One, Two, or Three or More Plan Types, by Firm Size, 2014

Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Firms That Offer the Following Plan Types, by Firm Size, 2014

Section Five: Market Shares of Health Plans

Enrollment remains highest in PPO plans, covering more than half of covered workers, followed by HDHP/SOs, HMO plans, POS plans, and conventional plans. Enrollment distribution varies by firm size, for example, PPOs are relatively more popular for covered workers at large firms (200 or more workers) than smaller firms (63% vs. 46%) and POS plans are relatively more popular among smaller firms than large firms (17% vs. 4%). Enrollment in HDHP/SO plans (20%) remains statistically unchanged from 2012 (19%).

- Fifty-eight percent of covered workers are enrolled in PPOs, followed by HDHP/SOs (20%), HMOs (13%), POS plans (8%), and conventional plans (<1%) (Exhibit 5.1).

- After years of significant annual increases in the percentage of covered workers enrolled in HDHP/SO plans (8% in 2009, 13% in 2010, and 17% in 2011), enrollment has remained steady over the past three years (19% in 2012, and 20% in 2013 and 2014) (Exhibit 5.1). The percentage of covered workers enrolled in HDHP/SO plans at both large firms (200 or more workers) and smaller firms is similar to last year.

- Enrollment in HDHP/SOs is similar for firms with many lower wage workers (at least 35% of workers earn $23,000 per year or less) and those with fewer lower wage workers as well as between large firms (200 or more workers) and smaller firms.

- Enrollment in HMO plans is similar to 2013 but declined significantly from two years ago (16% in 2012) and five years ago (20% in 2009).

- Plan enrollment patterns vary by firm size. Workers in large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely than workers in smaller firms to enroll in PPOs (63% vs. 46%). Workers in small firms are more likely than workers in large firms to enroll in POS plans (17% vs. 4%) (Exhibit 5.2).

- Plan enrollment patterns also differ across regions.

- HMO enrollment is significantly higher in the West (25%) and significantly lower in the South (9%) and Midwest (8%) (Exhibit 5.3).

- Workers in the South (66%) are more likely to be enrolled in PPO plans than workers in other regions; workers in the West (51%) are less likely to be enrolled in a PPO (Exhibit 5.3).

- Enrollment in HDHP/SOs is higher among workers in the Midwest (27%) than in other regions (Exhibit 5.3).

- Plan enrollment patterns differ by industry as well.

- Covered workers in the state/local government industry (11%) are significantly less likely to be enrolled in an HDHP/SO plan than covered workers in other industries (Exhibit 5.3).

Section Six: Worker and Employer Contributions for Premiums

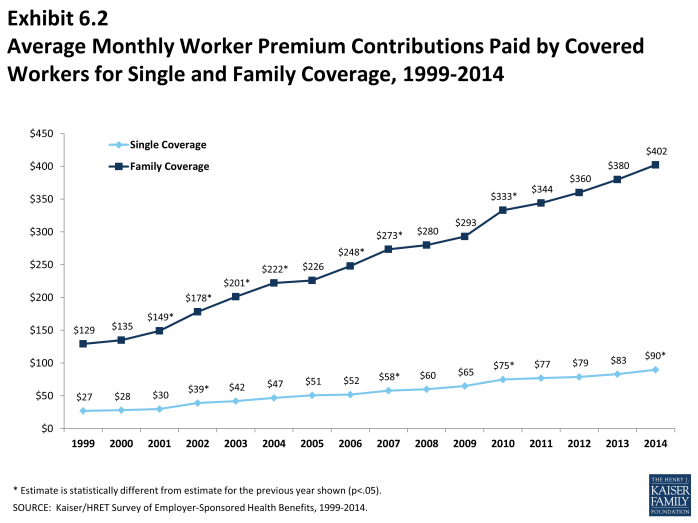

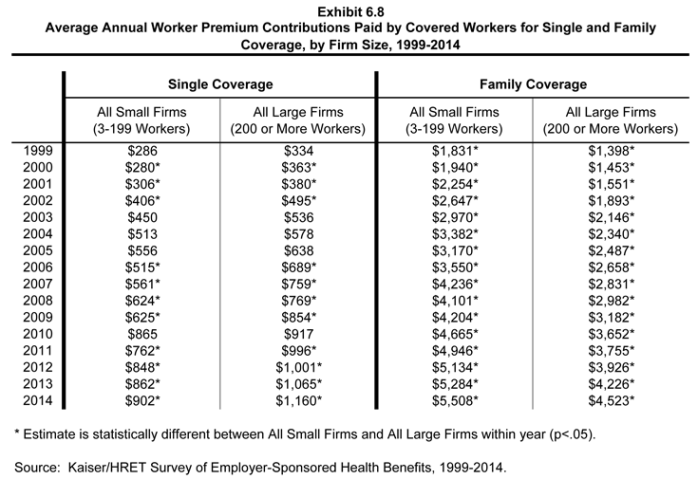

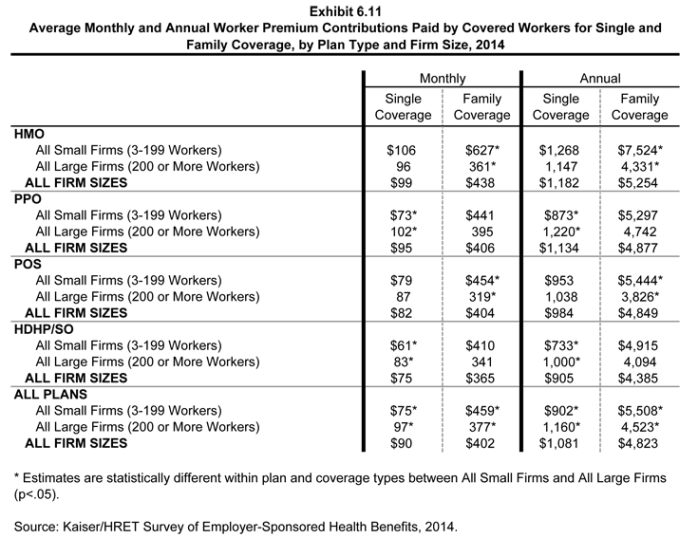

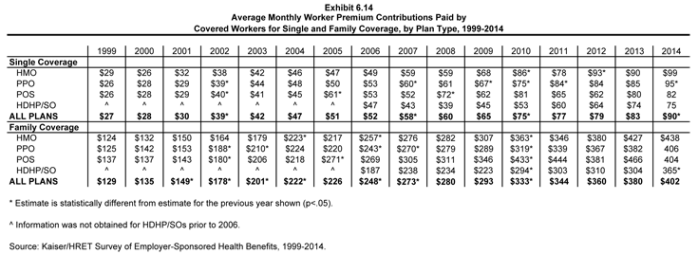

Premium contributions by covered workers average 18% for single coverage and 29% for family coverage.1 The average monthly worker contributions are $90 for single coverage ($1,081 annually) and $402 for family coverage ($4,823 annually). On average covered workers contribute a similar amount for family coverage in 2014 as they did in 2013 but more for single coverage ($90 vs. $83). There continues to be important differences by firm size; covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) contribute a lower percentage of the premium for single coverage (16 percent versus 19 percent) but a much higher percentage of the premium for family coverage than covered workers in larger firms (35 percent versus 27 percent).

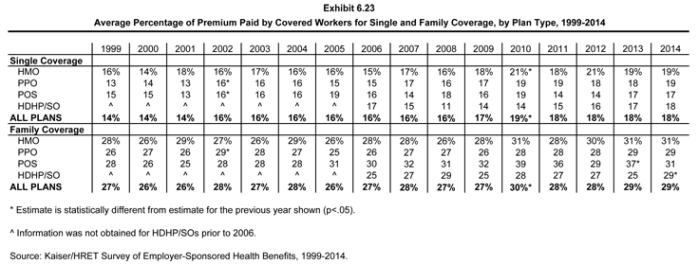

- In 2014, covered workers on average contribute 18% of the premium for single coverage and 29% of the premium for family coverage the same contribution percentages reported in 2013 (Exhibit 6.1). These contributions have remained stable since 2010 for both single and family coverage.

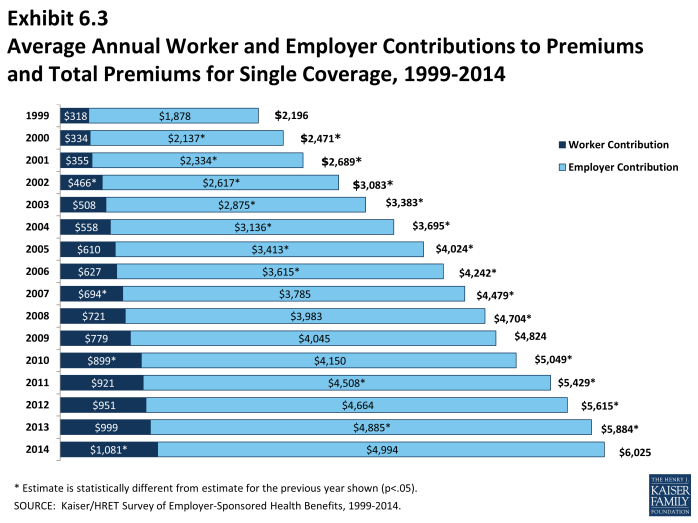

- On average, workers with single coverage contribute $90 per month ($1,081 annually), and workers with family coverage contribute $402 per month ($4,823 annually), towards their health insurance premiums, similar to the amounts reported in 2013 for family coverage, but significantly higher for single coverage (Exhibit 6.2), (Exhibit 6.3), and (Exhibit 6.4).

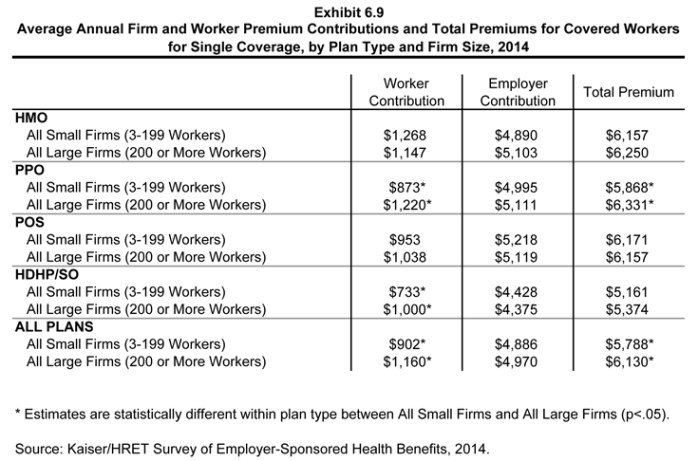

- Worker contributions in HDHP/SOs are lower than the overall average worker contributions for single coverage ($905 vs. $1,081) (Exhibit 6.5). While employers contribute less for family coverage in HDHP/SO plans, the worker contribution is similar to the overall average.

- Worker contributions in other plan types are not statistically different from the overall average for either single or family coverage (Exhibit 6.5).

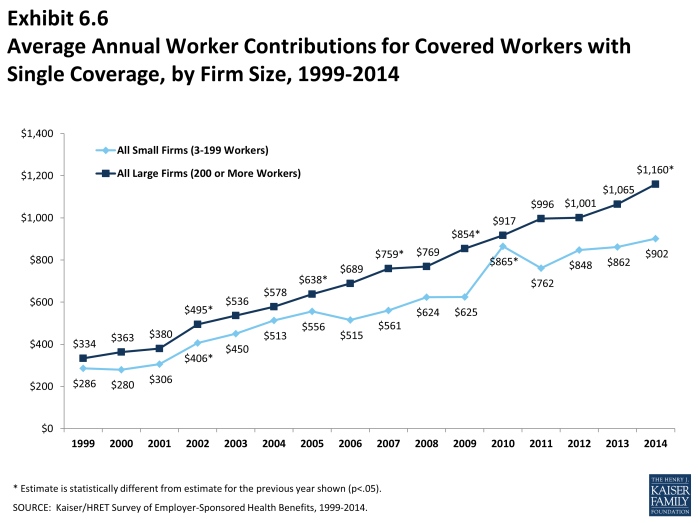

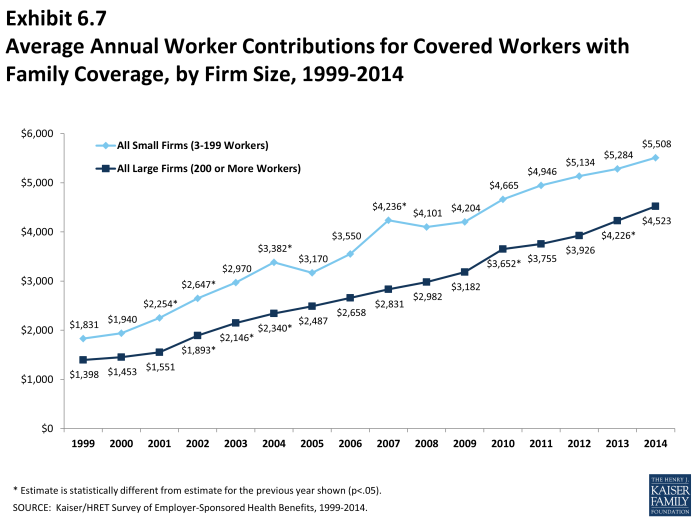

- In addition to differences between plan types, there are differences in worker contributions by type of firm. As in previous years, workers in small firms (3-199 workers) contribute a lower amount annually for single coverage than workers in large firms (200 or more workers), $902 vs. $1,160. In contrast, workers in small firms with family coverage contribute significantly more annually than workers with family coverage in large firms ($5,508 vs. $4,523) (Exhibit 6.8). One reason small firms may contribute a higher percentage for single coverage and a lower percentage for family coverage, compared to large firms, is to incentivize enrollment. Many insurers impose participation requirements on firms purchasing small-group coverage.

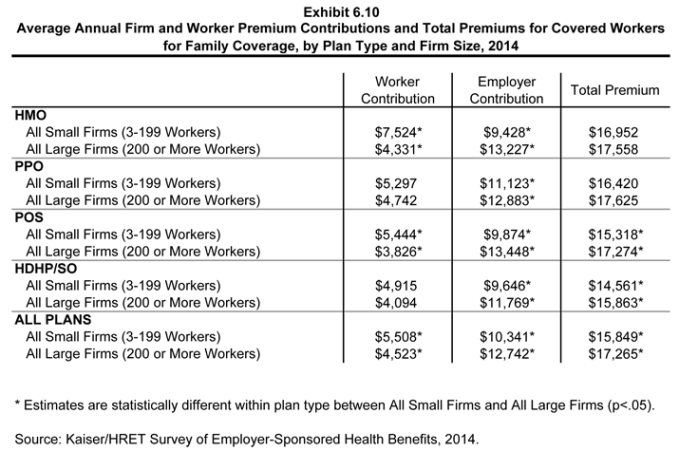

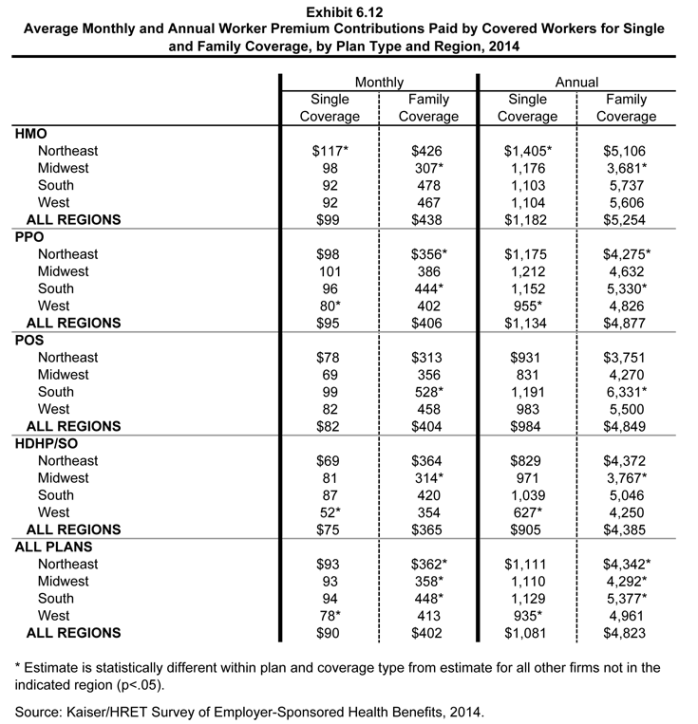

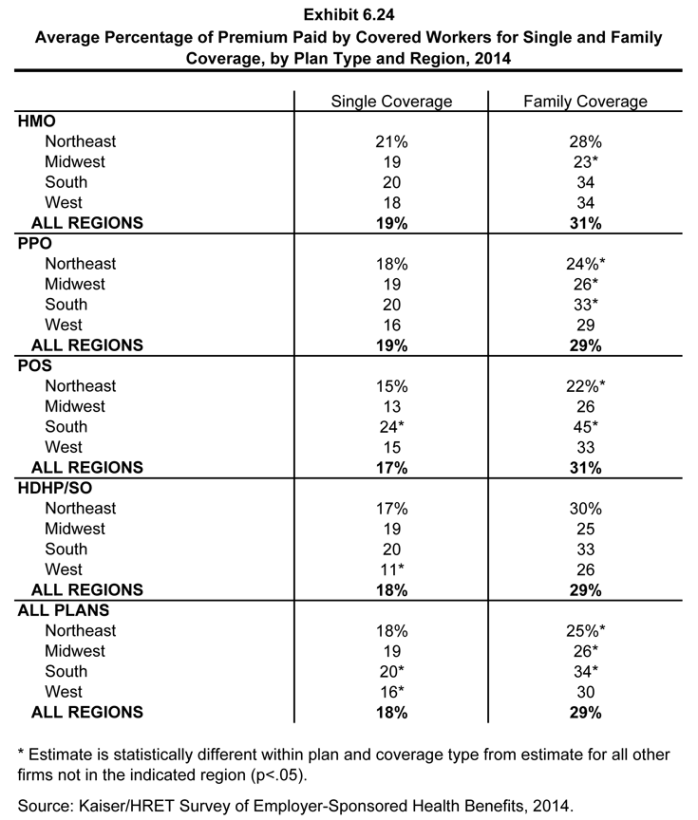

- The average worker contribution for family coverage in the South is higher than the average for covered workers in all other regions (Exhibit 6.12). The average employer contribution is higher for covered workers in large firms ($12,742 vs. $10,341) (Exhibit 6.10).

Variation in Worker Contributions to the Premium

- There is a great deal of variation in worker contributions to premiums.

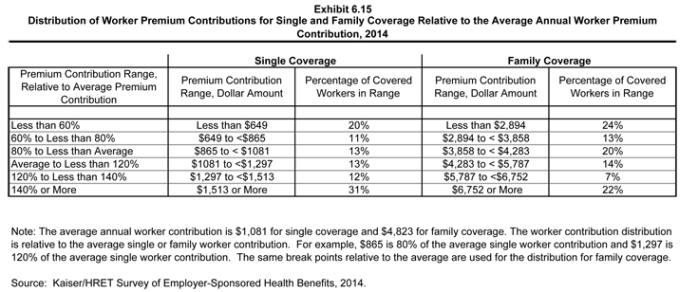

- Thirty-one percent of covered workers contribute $1,513 or more annually (140% or more of the average worker contribution) for single coverage, while 20% of covered workers have an annual worker contribution of less than $649 (less than 60% of the average worker contribution) (Exhibit 6.15).

- For family coverage, 22% of covered workers contribute $6,752 or more annually (140% or more of the average worker contribution), while 24% of covered workers have an annual worker contribution of less than $2,894 (less than 60% of the average worker contribution) (Exhibit 6.15).

- The majority of covered workers are employed by a firm that contributes at least half of the premium for single and family coverage.

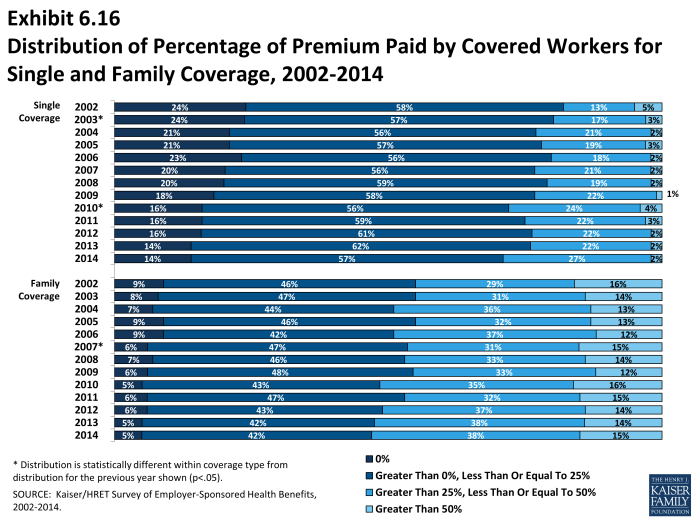

- Fourteen percent of covered workers with single coverage and 5% of covered workers with family coverage work for a firm that pays 100% of the premium (Exhibit 6.16).

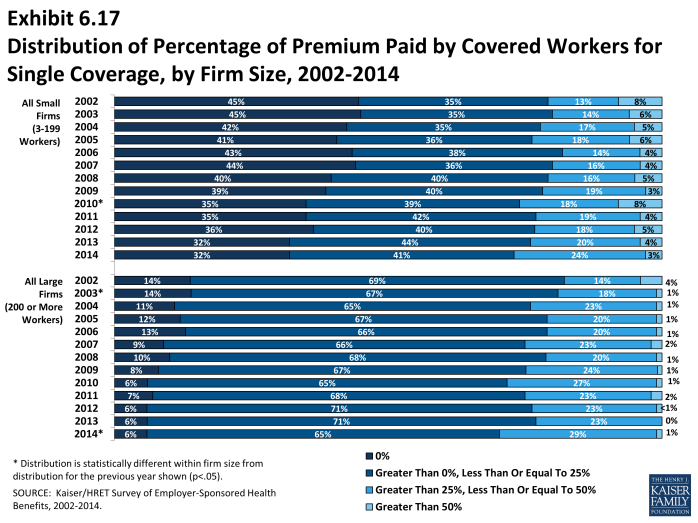

- Covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) are more likely to work for a firm that pays 100% of the premium for single coverage than workers in large firms (200 or more workers). Thirty-two percent of covered workers in small firms have an employer that pays the full premium for single coverage, compared to 6% of covered workers in large firms (Exhibit 6.17). For family coverage, 14% of covered workers in small firms have an employer that pays the full premium, compared to 2% of covered workers in large firms (Exhibit 6.17) and (Exhibit 6.18).

- Three percent of covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) contribute more than 50% of the premium for single coverage, compared to one percent of covered workers in large firms (200 or more workers) (Exhibit 6.17). For family coverage, 31% of covered workers in small firms work in a firm where they must contribute more than 50% of the premium, compared to 9% of covered workers in large firms (Exhibit 6.17) and (Exhibit 6.18).

Difference by Firm Characteristics

- The percentage of the premium paid by covered workers varies by several firm characteristics.

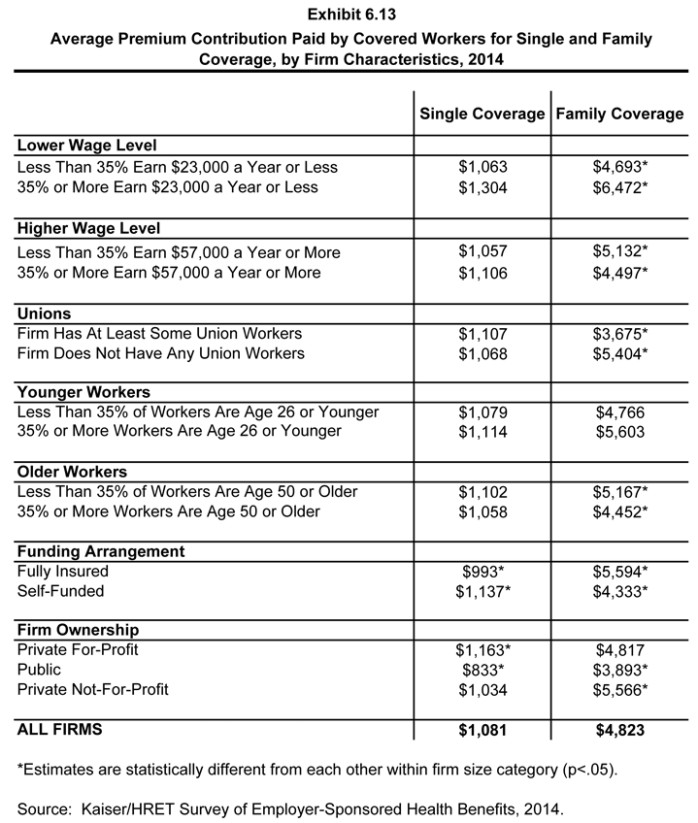

- For family coverage, covered workers in firms with many lower-wage workers (35% or more earn $23,000 or less annually) contribute a greater percentage of the premium than those in firms with fewer lower-wage workers (44% vs. 28%) (Exhibit 6.21).

- Looking at dollar amounts, covered workers in firms with many lower-wage workers (35% or more earn $23,000 or less annually) on average contribute $6,472 for family coverage versus $4,693 for covered workers in firms with fewer lower-wage workers (Exhibit 6.13). Forty-two percent of covered workers at firms with many lower wage workers pay more than 50% of the premium for family coverage in contrast to 13% at firms with fewer lower wage workers (Exhibit 6.19).

- Covered workers with family coverage in firms that have at least some union workers contribute a significantly lower percentage of the premium than those in firms without any unionized workers (21% vs. 34%) (Exhibit 6.21).

- For workers with family coverage in large firms (200 or more workers), the average percentage contribution for workers in firms that are partially or completely self-funded is lower than the average percentage contributions for workers in firms that are fully insured (26% vs. 31%)2 (Exhibit 6.21).

- Covered workers in private, for profit firms contribute a significantly higher percentage of the premium for single coverage (21%) than do workers in private not-for-profit firms (16%) and public organizations such as state or local governments (13%) (Exhibit 6.20).

Other Topics

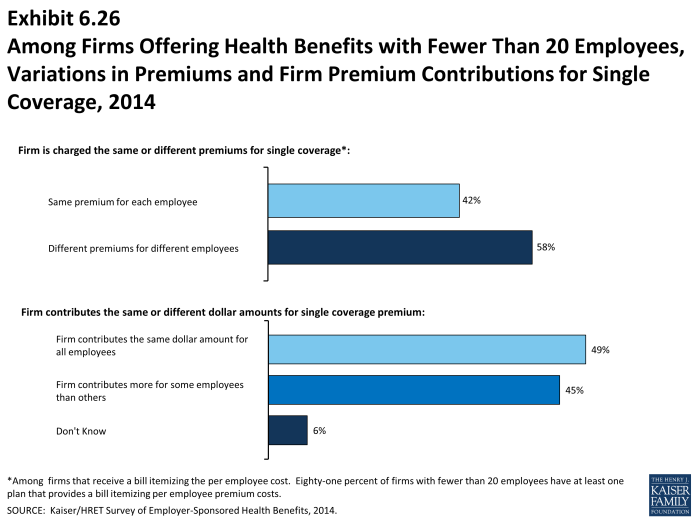

- Among firms offering health benefits with fewer than 20 employees, 45% contribute different dollar amounts toward premiums for different employees (Exhibit 6.26). Employer may contribute different amounts to different employees based for a variety of reasons, including workers’ age, smoking status, seniority, job title or location.

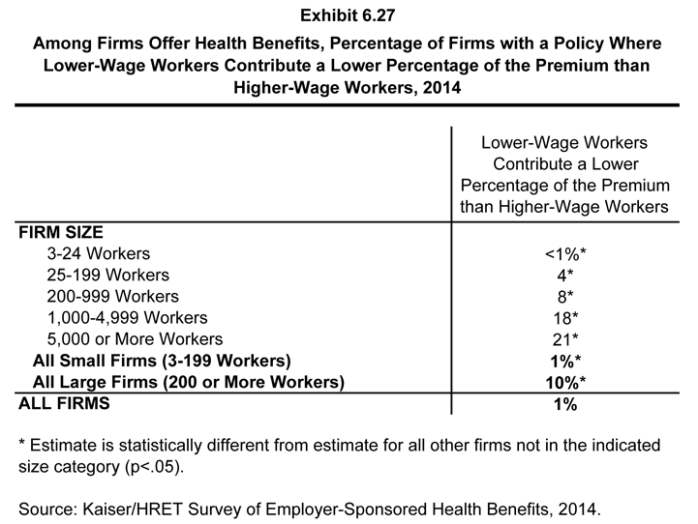

- Among firms offering health benefits, one percent of small firms (3 to 199 workers) and 10% of larger firms have a policy where lower wage workers contribute a lower percentage of the premium than higher wage workers (Exhibit 6.27).

Changes over Time

- The amount which workers contribute to single coverage premiums has increased 94% since 2004 and 39% since 2009. Covered workers’ contributions to family coverage have increased 81% since 2004 and 37% since 2009. Over the last five years the average worker contribution for single and family coverage has risen at a similar rate.

- Over the last ten years the average worker contribution for family coverage has risen faster for large firms (200 or more workers) than smaller firms (63% vs. 93%). The average worker contribution for family coverage has risen at a similar rate for firms with many low income workers (35% or more earn $23,000 or less annually) and those with fewer low income workers over the past ten years.

Section Six: Worker and Employer Contributions for Premiums

exhibits

Average Monthly Worker Premium Contributions Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, 1999-2014

Average Annual Worker and Employer Contributions to Premiums and Total Premiums for Single Coverage, 1999-2014

Average Annual Worker and Employer Contributions to Premiums and Total Premiums for Family Coverage, 1999-2014

Average Annual Firm and Worker Premium Contributions and Total Premiums for Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type, 2014

Average Annual Worker Contributions for Covered Workers with Single Coverage, by Firm Size, 1999-2014

Average Annual Worker Contributions for Covered Workers with Family Coverage, by Firm Size, 1999-2014

Average Annual Worker Premium Contributions Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Firm Size, 1999-2014

Average Annual Firm and Worker Premium Contributions and Total Premiums for Covered Workers for Single Coverage, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2014

Average Annual Firm and Worker Premium Contributions and Total Premiums for Covered Workers for Family Coverage, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2014

Average Monthly and Annual Worker Premium Contributions Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2014

Average Monthly and Annual Worker Premium Contributions Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type and Region, 2014

Average Premium Contribution Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Firm Characteristics, 2014

Average Monthly Worker Premium Contributions Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type, 1999-2014

Distribution of Worker Premium Contributions for Single and Family Coverage Relative to the Average Annual Worker Premium Contribution, 2014

Distribution of Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, 2002-2014

Distribution of Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Single Coverage, by Firm Size, 2002-2014

Distribution of Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Family Coverage, by Firm Size, 2002-2014