Implications of CMS’s New “Healthy Adult Opportunity” Demonstrations for Medicaid

On January 30, 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released guidance inviting states to apply for new Section 1115 demonstrations known as the “Healthy Adult Opportunity” (HAO). These demonstrations would permit states “extensive flexibility” to use Medicaid funds to cover Affordable Care Act (ACA) expansion adults and other nonelderly adults covered at state option who do not qualify on the basis of disability, without being bound by many federal standards related to Medicaid eligibility, benefits, delivery systems, and program oversight. In exchange, states would agree to a limit on federal financing in the form of a per capita or aggregate cap. States that opt for the aggregate cap and meet performance standards could access a portion of federal savings if actual spending is under the cap.

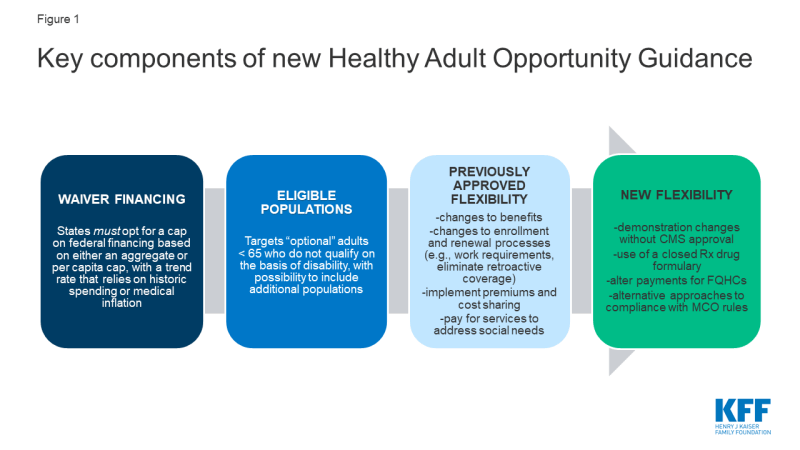

HAO demonstrations differ from other Medicaid demonstrations already granted by this Administration in several ways, including the scope of flexibility offered to states and the capped federal funding. This issue brief explains the key elements of the HAO guidance (Figure 1) and considers the implications of the new demonstrations.

Background

Today, states operate their Medicaid programs within federal minimum standards and a wide range of state options in exchange for federal matching funds that are available with no limit. The matching structure provides states with resources that automatically adjust for demographic and economic shifts, health care costs, public health emergencies, natural disasters and changing state priorities. In exchange for the federal funds, states must meet federal standards that reflect the program’s role covering a low-income population with limited resources and often complex health needs. Over time, states have transformed and updated their Medicaid programs to adopt new service delivery models, payment strategies, and quality initiatives.

Capped financing can present challenges for health programs. Unlike Medicaid in the states, the U.S. territories operate Medicaid under a federal cap, which has been set too low to meet enrollees’ needs and inflexible when responses to emerging health issues and natural disasters are required. Another capped entitlement, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), has been successful mainly because most states administer CHIP in conjunction with Medicaid (which is not capped), and the federal funding caps for CHIP have been set at levels that have not required states to make substantial program cuts. However, requirements to reauthorize federal CHIP funding and past failure of Congress to act timely resulted in state budget issues and confusion for some enrollees.

Use of block grants in Medicaid has been debated before, dating back to the Reagan administration and most recently as part of the 2017 ACA repeal and replace debate. Under these legislative proposals, which would have applied to all states, federal funding for Medicaid could have been reduced by more than one-third over the next two decades below the projected baseline. Analysis of previous block grant proposals finds that reductions in funding and federal caps shift risk to states; coupled with additional state flexibility, enrollees could face fewer guaranteed benefits and less coverage compared to current law. Congress also considered the 2017 Graham-Cassidy legislation that would have ended federal funding for the ACA, partially replaced that funding with a block grant (for the Medicaid expansion and other Medicaid populations), and redistributed funds across states. A similar proposal was included in the President’s FY 2020 budget proposal. Congress failed to enact these proposals, and polling at the time showed that the public opposed block grants.

The Trump administration has used Section 1115 authority to implement substantial policy changes to the Medicaid program. Previous administrations also have used Section 1115 authority to advance policy priorities, but the Trump administration marked a new direction for Medicaid demonstrations beginning with the release of revised demonstration approval criteria in November 2017 that no longer included expanding coverage among the stated objectives. Section 1115 demonstrations issued under the Trump administration to date have included state programs to condition Medicaid eligibility on fulfillment of work and reporting requirements; use of premiums, copayments, and benefit restrictions not otherwise allowed under federal law; and behavioral health programs to use Medicaid funds for inpatient psychiatric hospital payments, among others. Most of these demonstrations were authorized through Section 1115 (a) (1) authority, which allows the HHS Secretary to waive state compliance with certain provisions in Section 1902 of the statute. In a few instances, the Administration has used Section 1115 (a) (2) authority, which allows the Secretary to approve federal matching funds for state spending on costs not otherwise matchable (CNOM). For example, more than half of all states have demonstrations to pay for services in “institutions for mental disease” (IMDs) for adults age 21-64, an expense not otherwise allowable under the law. The HAO demonstrations also will use Section 1115 (a) (2) expenditure authority, which CMS maintains enables the Secretary to permit states to “not apply” federal Medicaid requirements to expenditures for individuals covered under the HAO demonstrations. While previous administrations have relied on Section 1115 (a) (2) for coverage expansions, they did so before there was legal authority under the ACA to cover those populations. In using Section 1115 (a) (2), this Administration is inviting states to choose from a “menu” of provisions included in other approved demonstrations to date, and it is offering states the opportunity to modify or eliminate some program rules not previously granted.

Key Provisions of HAO Demonstrations

Financing

The HAO demonstrations will be subject to an annual federal spending cap. States will choose whether to use an aggregate cap or a per capita cap. States opting for an aggregate cap will be subject to that cap without regard to changes in Medicaid enrollment; the cap for states opting for a per capita cap is calculated based on the number of enrollees, times the maximum allowable spending per person. In both cases, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will establish a base amount for the cap using recent spending data and will trend that amount forward. The trend factor will be the lesser of the prior five year state average Medicaid spending growth or medical inflation (CPI-M) for the per capita cap, or CPI-M +.5% for the aggregate cap. For states electing the per capita cap, funding would reflect the trend plus enrollment growth. The guidance also says that CMS will adjust the base amount or subsequent annual caps to account for state flexibilities that could significantly affect enrollment to ensure that states do not achieve savings from disenrolling individuals. States will continue to submit claims reflecting actual expenditures to draw down federal matching funds. States that expand coverage to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) can receive enhanced matching funds for ACA expansion adults.

The HAO spending caps differ from current methods used to determine budget neutrality for demonstrations. By long-standing policy, Section 1115 demonstrations are required to be budget neutral to the federal government (i.e., the federal government cannot spend more than it would have spent in the absence of the demonstration). Budget neutrality is calculated by establishing a “without waiver” baseline of expected costs and then comparing that baseline to expected spending under the demonstration. These determinations are typically calculated over the entire term of the demonstration (usually five years) and also typically calculated on a per member per month basis. However, budget neutrality can also be calculated using an aggregate cap. In the past, capped demonstrations have been approved in Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia (for a limited population), but they are no longer in place in these states. Under the HAO, caps will be enforced annually (not over the term of the demonstration).

In exchange for taking on greater risk, states choosing an aggregate cap can obtain 25 to 50% of federal savings if spending is below the cap and performance benchmarks are met. Shared savings can be used for existing state-funded health programs or new health-related initiatives targeted to demonstration or other Medicaid enrollees or to offset expenditures that exceed the cap for up to three years. This policy seems to stand in contrast with earlier guidance that would not allow federal funds for designated state health programs (DSHP). Shared savings are available to states on a matched basis at their regular matching rate. States that do not spend at least 80% of their cap annually (combined federal and state spending) will have their cap reduced in subsequent years. States that access shared savings must spend those funds within three years after the demonstration period. States extending coverage to new populations under HAO demonstrations must first implement through a per capita cap model before switching to an aggregate cap model to be eligible for shared savings.

States would be able to propose adjustments to an approved cap to account for changes in projected expenditures or enrollment due to unforeseen circumstances outside the state’s control such as a public health crisis or major economic event. For populations newly covered under an HAO demonstration, CMS will estimate expenditures based on national averages and state specific factors but will re-base the estimate if actual expenditures exceed a specified margin above or below the base. Such adjustments, along with opportunities for shared savings, mitigate the risks for states. Analyses of historic per enrollee growth showed that 47 states would have experienced declines in spending if per enrollee spending for adults had been limited to CPI-M for 2001-2011, though growth in per enrollee health care spending in Medicaid and more broadly has slowed since then. Certain expenditures will be excluded from the HAO caps including disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, administrative expenditures, expenditures for public health emergencies, expenditures for Indian Health Services (IHS) matched at 100%, and a portion of supplemental payments that could be attributable to the population included in the demonstration.

Eligibility

States could include in HAO demonstrations ACA expansion adults and other adults under age 65 that do not qualify on the basis of disability. These other adult groups include low-income parents and pregnant women covered at state option and other populations currently covered under Section 1115 demonstration authority. All children, mandatory pregnant women (those with incomes up to 138% FPL), mandatory low-income parents (those up to the state’s 1996 cash assistance levels), and adults eligible based on a disability or long-term care need are excluded from the new demonstrations. Still, some people included in HAO demonstrations may have functional or other disabilities, as a large share of Medicaid adults have such disabilities even though they do not qualify on the basis of a disability. The guidance also notes that CMS may consider state requests to include other adult populations who are not covered under the state plan, which may open these demonstrations up to additional adult populations. States could use HAO demonstrations to extend coverage to groups not already covered. States also could terminate current state plan authority for optional groups and move that coverage to an HAO demonstration with additional restrictions.

States could limit eligibility for certain adults under HAO demonstrations. States could set an income limit for expansion adults below 138% FPL and apply an asset test to limit eligibility for any demonstration enrollees. However, states can only receive enhanced matching funds for ACA expansion adults if they cover the full expansion population (all adults with incomes up to 138% FPL) without an asset test. Under the ACA, asset tests are not allowed for low-income parents, pregnant women, and expansion adults. States also can use HAO demonstrations to cover a subset of ACA expansion adults (at the regular matching rate), using other (non-financial) criteria, such as establishing geographic limits or restricting coverage to people with specific illnesses, such as behavioral health diagnoses.

Under the HAO demonstrations, states could limit Medicaid eligibility in other ways not allowed by current law. States could impose additional eligibility requirements, such as work requirements or other criteria that individuals must meet to gain coverage. States also could eliminate 3-month retroactive eligibility and delay the effective coverage date beyond the eligibility determination. For example, states could require that coverage does not begin until an individual enrolls in a health plan, which could involve paying the first month’s premium. States also could require premiums for enrollees at any income level and at any amount, subject only to a cap of 5% of income, and suspend coverage for those who fail to pay after a grace period (other than tribal members, those with substance use disorders, and those with HIV). States could also make changes to current rules around enrollment and renewal processes. For example, states could conduct the initial eligibility renewal sooner than the current 12-month requirement (to align with the Marketplace) and eliminate the ability for hospitals to determine individuals “presumptively” eligible – changes that could reduce enrollment. However, states also could apply 12-month continuous eligibility to demonstration enrollees which could reduce enrollment churn.

Benefits and Cost-Sharing

The HAO demonstrations would allow states to limit covered benefits compared to current law. States would not have to provide the full Medicaid alternative (formerly known as benchmark) benefit package to demonstration enrollees. For example, states could eliminate non-emergency medical transportation and Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment Services (EPDST) for 19 and 20 year olds. Instead, states only need to cover the 10 categories of essential health benefits (EHB) available in Marketplace plans and would have flexibility beyond current law to determine the appropriate amount, duration, and scope of covered services. States could receive enhanced ACA matching funds for expansion adults without providing the full benchmark benefit package as required by current law. States also could seek authority to cover additional services that would improve health outcomes and “address certain health determinants to promote independence.”

States could establish closed prescription drug formularies, a change from current Medicaid rules that generally require states to include all FDA-approved drugs from manufacturers with Medicaid rebate agreements. While the guidance provides that states can use formularies, it stipulates that manufacturers are still obliged to pay rebates under the Medicaid drug rebate program. In addition to EHB requirements, which require coverage of the greater of at least one drug in each drug category and class (with an exceptions process) or the same number of drugs in each category and class as the base benchmark plan used to define EHB, prescription drug formularies under the demonstrations would have to cover substantially all mental health and antiretroviral drugs and all FDA approved drugs with rebate agreements to treat opioid use disorder.

States would have broader authority to impose cost-sharing on enrollees. States could impose cost sharing for any service on any enrollee (other than tribal members, those with substance use disorder, those with HIV, and mental health drugs) above the currently allowed nominal amounts, subject only to the 5% of income out of pocket cap (including premiums and cost-sharing).

Delivery System

States could not follow and/or propose alternative approaches that differ from current federal Medicaid managed care regulations, including access to care and rate certification standards. For example, states would not have to obtain prospective CMS review of actuarially sound capitation rates or CMS approval of health plan contract amendments. States also could adopt alternative provider network adequacy standards and propose alternative approaches to other federal managed care requirements. In addition, while CMS acknowledges that fair hearings are constitutionally required, it will permit states to “not implement” and streamline portions of these processes for all HAO enrollees.

States could deviate from current federal rules with respect to payment and delivery system under HAO demonstrations. For example, states could use value-based payment (VBP) for federally-qualified health centers (FQHCs), which are currently paid under a Prospective Payment System (PPS) that ties payments to the costs of delivering care. VBPs to health centers may limit payment for only certain services, lower their payment, or make payment contingent on meeting certain outcomes. Elimination of hospital presumptive eligibility could also lower payment to hospitals. States are encouraged to pursue delivery system changes under the demonstrations to “promote competition” and incorporate models currently being tested by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI). States also could limit enrollees’ free choice of fee-for-service provider based on state-established standards for reimbursement, quality and utilization.

Oversight and Evaluation

Once a 5-year demonstration is approved, states can make “administrative and programmatic changes” without prior CMS approval, unless the change “has the potential to substantially impact enrollment.” For example, states could change premium and cost sharing amounts or EHB benchmark plans or eliminate optional benefits during the course of the demonstration without submitting a demonstration amendment to CMS. States must report quarterly on 13 performance metrics in the areas of enrollment, retention, access to care, and financial management, and CMS will use rapid cycle evaluation for mid-course corrective action if state cannot correct problems related to enrollee access to coverage or care. States will also be subject to the evaluation requirements standard for all Section 1115 demonstrations.

CMS maintains that these new demonstrations will advance program objectives. Specifically, CMS states that the demonstrations will advance program objectives by “furnishing medical assistance in a manner that promotes the sustainability of government health care spending” and will require states to evaluate their demonstrations to determine whether the additional flexibilities “enable states to more efficiently administer their Medicaid programs” as well as the demonstration’s impact on enrollees. As recent litigation on work requirements shows, the stated goals of the demonstrations have implications for their legality. Those lawsuits have been decided based on the finding that the primary objective of the Medicaid program is to provide affordable coverage to low-income people, which is not highlighted as a program objective for the HAOs.

What to Watch

The HAO guidance, in giving states significantly greater leeway in operating Medicaid programs within a cap on federal spending, is consistent with the Trump administration’s previous support for block grants in the President’s budget proposals and its position in the debate over repealing and replacing the ACA. Unlike past proposed legislative changes, demonstrations under this new guidance would not apply to all states. While states opting for HAO demonstrations would be given greater flexibility compared to current law, they would also face fiscal risks in accepting capped federal funding. The breadth of the new flexibility could also result in limits on coverage and access to care for current enrollees and potentially limit the reach of the ACA Medicaid expansion through the HAO demonstrations, compared to coverage of new enrollees under current law.

Overall, the HAO demonstrations could cover nearly 30 million adults if adopted in all states. This total includes approximately 13 million adults newly covered through the ACA Medicaid expansion, 10 million adults currently covered through other state options (using the estimate that 16.1% of Medicaid enrollees are adults covered at state option without accounting for the ACA expansion), and nearly five million uninsured low-income adults in non-expansion states who could be eligible for Medicaid if the state adopted the expansion.

The HAO guidance would make significant changes to the Medicaid program in the absence of federal legislation, which will likely subject it to legal challenges. Under the HAO, states could access substantial flexibility to provide Medicaid coverage, with various eligibility and benefit restrictions, to many adults in exchange for taking on the risk of capped financing. Oklahoma plans to develop an HAO demonstration proposal that could access Medicaid expansion funding, amid efforts to put the Medicaid expansion question to voters on the ballot in November 2020. While a number of states pursued work requirements promoted under other Section 1115 demonstration guidance, those efforts have been challenged in the courts. The debate has demonstrated the tension and limits on how far an administration can go in implementing significant policy changes to Medicaid through demonstration authority. The HAO guidance is likely to set up a similar tension. Looking ahead, the following questions will be important to follow:

- Which states will seek HAO demonstration authority?

- What populations will states seek to cover in such demonstrations? To what extent will states move current coverage for adults to HAO demonstrations or extend coverage to new groups, such as low-income adults in states that have not previously expanded Medicaid under the ACA? How will the eligibility criteria and benefits differ from what would be provided under federal law?

- What share of HAO enrollees will qualify for the 90% ACA expansion enhanced federal matching rate?

- What will the demonstrations mean for federal spending compared to current law? Will states achieve savings, how will the caps be determined in practice and will those caps be set at levels that are binding and require program cuts?

- What legal challenges will these demonstrations face and will those challenges stall implementation?