A Closer Look at the $50 Billion Rural Health Fund in the New Reconciliation Law

Editorial Note: Originally published on July 16, this brief is being updated regularly as new information becomes available.

On July 4, 2025, President Trump signed a budget reconciliation bill into law that includes significant reductions in federal health care spending, large tax cuts, and other changes. The new law will reduce federal Medicaid spending alone by $911 billion over ten years and lead to 10 million more people becoming uninsured by 2034 based on Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates. While this legislation was being debated, Members of Congress from both parties raised concerns about the potential impact on rural hospitals, particularly given the ongoing trend of rural hospital closures. In response, and just prior to passage, the Senate added $50 billion in funding for a new “rural health transformation program,” referred to here as the “rural health fund.”

This brief describes the rural health fund, explains what the law says about the allocation of funds, and highlights outstanding questions about how the funds will be distributed across and within states to pay rural hospitals and for other purposes. Based on the statutory language, it is not yet clear what specific criteria the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will ultimately use to approve or deny state applications and distribute funds across states; what share of the $50 billion fund will go to rural areas; what share will go to the nearly 1,800 hospitals in rural areas or be used for other providers or purposes; whether funds will be targeted to certain types of rural hospitals, such as the 44% of rural hospitals with negative margins; and to what extent the CMS Administrator will be able to influence how states use their funds prior to approving an application. Further, the law does not require CMS to publish information about the distribution of funds so that the allocation decisions are transparent. Similar questions were raised during the COVID-19 pandemic about how well provider relief funds were targeted to hospitals with the greatest need.

The rural health fund includes $50 billion, which is a little over one third (37%) of the estimated loss of federal Medicaid funding in rural areas

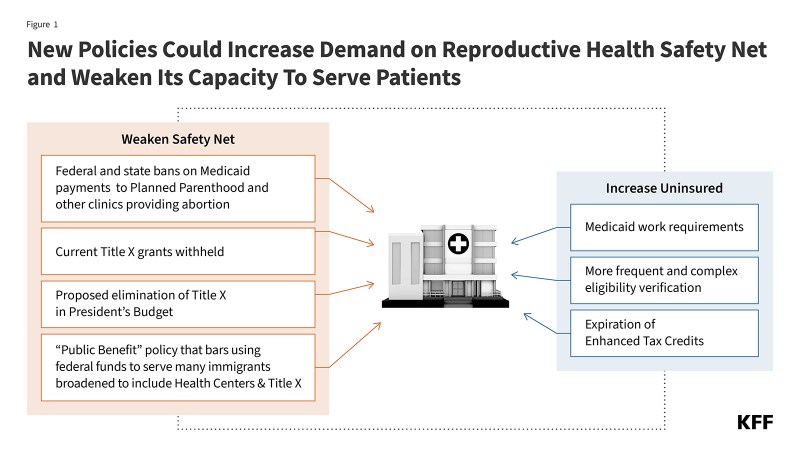

The fund provides $50 billion for state grants (DC and the U.S. territories cannot apply). Half ($25 billion) will be distributed by CMS “equally among all states with an approved application,” which appears to suggest that each state with an approved application would receive the same amount from this pool regardless of the size of its rural population, the number of rural hospitals or other providers in the state, the financial standing of its rural hospitals, or other factors. For example, Connecticut (which has 3 rural hospitals based on one definition) could receive the same amount as Kansas (which has 90 rural hospitals) if both are approved for funding. CMS will have some discretion in determining how to allocate the remaining half ($25 billion) (see Figure 1 and more details below).

States can apply to use the funds in a variety of ways, such as for promoting care interventions, paying for health care services, expanding the rural health workforce, and providing technical assistance with system transformation.

The $50 billion in new funding could offset a little over a third (37%) of the estimated cuts to federal Medicaid spending in rural areas ($137 billion over ten years) based on KFF analysis of CBO’s estimates, or about 5% of the total estimated cuts to federal Medicaid spending ($911 billion over ten years). This does not account for other revenue losses related to the bill, including cuts to federal spending for the ACA Marketplaces, or the revenue losses stemming from the increased number of people who will be uninsured because of the expiration of the enhanced ACA premium tax credits and the implementation of final Marketplace integrity rules. The impact of these changes on rural areas, and the extent to which the rural health fund offsets losses, will vary across the country.

The rural health fund will be temporary, while many of the cuts in health spending are not time limited

While many of the major cuts related to Medicaid and the ACA Marketplaces under the law are not time limited, the rural health fund is temporary. The law provides $10 billion per year through the rural health fund for fiscal years 2026 through 2030, a five-year period. According to statements made by the CMS Administrator, CMS will distribute applications to states in early September 2025, states will submit applications to CMS in that month, and CMS will process their applications in November and send out the first batch of funds at the end of the year. States will be allowed to spend funds that they receive at a given point through the end of the following fiscal year, and CMS may be able to redistribute some unused funds over time, but all funds must be spent before October 1, 2032. New legislation would be required to provide additional support to rural areas after the funds dry up.

The distribution of dollars from the rural health fund will occur before many of the health care spending cuts under the law are fully realized. The rural health fund was put in place, and doubled in size, to address concerns of lawmakers from rural states, and front loading these dollars could allow systems to absorb forthcoming cuts. As described above, the law specifies that rural health fund dollars will first be available for fiscal year 2026, with $10 billion dollars available per year over five years through fiscal year 2030, and all funds must be spent before October 1, 2032. Yet most of the health care spending reductions are backloaded and occur after fiscal year 2030. For example, based on KFF’s analysis of CBO estimates, nearly two thirds (64%) of the ten-year reductions in federal Medicaid spending would occur after fiscal year 2030.

CMS will have broad leeway in how it distributes funds across states

The law grants CMS broad discretion over the distribution of funds and confirms that these decisions are not subject to administrative or judicial review. The law gives CMS authority to determine which state applications to approve or deny, without specifying the criteria CMS should use to make these decisions, though it does specify certain items that states must include in their applications.

As noted above, half of the funds ($25 billion) will be distributed equally among states with approved applications. For the second half of the funds ($25 billion), CMS has more flexibility. The law requires that CMS considers certain factors when distributing these funds (the share of the state population that lives in a rural part of a metropolitan area, the share of rural health facilities in the state as a share of all rural health facilities nationwide, and the situation of hospitals that serve a disproportionate number of low-income patients with special needs). It also allows the CMS Administrator to consider “any other factors that [it] determines appropriate.” CMS could choose to restrict this $25 billion pool of funds to a subset of states, though the law specifies that it must distribute these funds to at least a quarter of states with approved applications.

States will have discretion in how they distribute funds among hospitals, and other providers, and may be able to steer some dollars to nonrural areas, subject to CMS approval

Just as the law grants CMS broad discretion over the distribution of funds across states, it also permits states to use the funds for a wide variety of purposes, subject to CMS approval. States must use the funds for at least three of the following purposes:

- Promoting evidence-based, measurable interventions to improve prevention and chronic disease management.

- Providing payments to health care providers for the provision of health care items or services, as specified by the CMS Administrator.

- Promoting consumer-facing, technology-driven solutions for the prevention and management of chronic diseases.

- Providing training and technical assistance for the development and adoption of technology-enabled solutions that improve care delivery in rural hospitals, including remote monitoring, robotics, artificial intelligence, and other advanced technologies.

- Recruiting and retaining clinical workforce talent to rural areas, with commitments to serve rural communities for a minimum of 5 years.

- Providing technical assistance, software, and hardware for significant information technology advances designed to improve efficiency, enhance cybersecurity capability development, and improve patient health outcomes.

- Assisting rural communities to right size their health care delivery systems by identifying needed preventative, ambulatory, pre-hospital, emergency, acute inpatient care, outpatient care, and post-acute care service lines.

- Supporting access to opioid use disorder treatment services, other substance use disorder treatment services, and mental health services.

- Developing projects that support innovative models of care that include value-based care arrangements and alternative payment models, as appropriate.

- Additional uses designed to promote sustainable access to high quality rural health care services, as determined by the CMS Administrator.

Within the contours of this list, states could restrict the funds to rural hospitals or specific types of rural hospitals (such as those that are isolated and in financial distress) or they could use them for additional or different purposes, such as paying nursing facilities or recruiting clinical workers to rural areas.

While the fund is described as a “rural” program, the law appears to give states some ability to direct some of the dollars to urban and suburban areas, pending CMS approval. For example, most of the permitted uses in the list above do not specify that the funds would need to go to rural areas, such as the description of payments to hospitals and other providers and of support for opioid use treatment services, other substance use disorder treatment services, and mental health services. The current CMS Administrator indicated that nonrural areas could potentially receive money from the fund. The law also does not define “rural” when describing the scope of the program, meaning that states or the administration could do so broadly.

The law does not direct CMS or states to be transparent about the allocation and use of funds

CMS is not required to publish information about how the funds are distributed—such as by posting the amount sent to each state or why certain state applications were approved or denied—though it could choose to do so. States are required to submit annual reports to CMS on the use of the allotments. CMS could require states to disclose information about the amount they receive or the use of funds to the public.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.