California Efforts to Address Behavioral Health and SDOH: A Look at Whole Person Care Pilots

Introduction

The “California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal” (CalAIM) initiative was recently approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and launched in January 2022. CalAIM seeks to improve health outcomes and advance health equity for “Medi-Cal” (Medicaid) beneficiaries and other low-income people in the state. As of September 2021, over 13 million people were enrolled in Medi-Cal in California – the largest Medicaid program in the nation. CalAIM will leverage Medicaid as a tool to help address complex challenges, including behavioral health access, the health needs of people experiencing homelessness, and the complex clinical needs of justice-involved populations. Central to the demonstration is a person-centered approach, first authorized as “Whole Person Care” (WPC) pilots implemented through a waiver approved by the federal government under section 1115 of the Medicaid statute (known as “Medi-Cal 2020”). The WPC pilot program aimed to coordinate and integrate physical health, behavioral health, and social services for Medicaid enrollees with complex needs. Under CalAIM, the state will incorporate and transition WPC pilot services statewide through the state’s Medicaid managed care system. The California initiatives are part of a growing movement to better meet behavioral health needs and improve equity and health by addressing underlying social determinants.

As CalAIM launches, it is useful to take a closer look at the WPC pilot program and what has been learned to date from its implementation. This brief draws heavily on findings from the interim evaluation, which assessed WPC infrastructure development and implementation and analyzed whether WPC led to “better care and better health” within the first three years. In this brief, we explore key questions involving the WPC pilots, which may provide insights for other states pursuing or contemplating similar strategies for identifying and addressing the medical and non-medical or social needs of high-risk, high-utilizing Medicaid enrollees.

What Were Whole Person Care Pilots (WPC)?

In 2016, California began its “Whole Person Care” (WPC) pilot program, which aimed to coordinate and integrate physical health, behavioral health, and social services for Medicaid enrollees with complex needs. The WPC pilot program also aimed to increase integration and data sharing among county agencies, health plans, and community-based organizations. The pilot was authorized under the state’s Section 1115 waiver. California’s Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) selected 25 WPC pilots (spanning 26 counties) to participate in the program across the state.1 (See Appendix for a spotlight on San Francisco County’s WPC pilot.) Each individual WPC pilot program defined its target population and interventions, within state guidelines. The WPC pilots were scheduled to end in December 2020 but were extended through December 2021 under the state’s Section 1115 waiver.

Each WPC pilot included a “lead entity” and key community partners (called “participating entities”). Lead entities coordinated the pilot, collaborated with local community partners, and served as the single point of contact for DHCS. Lead entities included county health and health services agencies, healthcare systems, behavioral health departments, and a city municipality.2 Each WPC pilot included key community partners, including Medi-Cal managed care plans, county health agencies, other public agencies (e.g., county alcohol and substance use disorder programs, human services agencies, public health departments, criminal justice/probation entities, and housing authorities), and community-based providers.3 In their applications, approved WPC pilots enumerated specific roles of each participating entity in service provision, data management, and implementation of WPC programs. In the initial program years, WPC pilots focused heavily on developing data and administrative infrastructure for data sharing, case management, outreach and enrollment, performance, and quality improvement efforts.

WPC pilots targeted a number of high-risk populations with complex needs. Primary WPC target populations included high utilizers of health care (e.g., those with avoidable use of the emergency room and/or hospital admission), individuals experiencing homelessness or at-risk of homelessness, individuals with multiple chronic conditions, individuals with severe mental illness or substance use disorders (SMI/SUD), and justice-involved individuals. Nearly half (46%) of all pilot enrollees were homeless across target populations, and most were men, 50-64 years old, White, English speaking, and enrolled in managed care. Pilots classified 10% of enrollees as at-risk of homelessness and 6% as justice-involved. Beneficiaries had high rates of hypertension, substance use disorders, and mental health conditions, as well as high rates of service use (particularly SUD services and emergency department visits). Participation in the pilot program was voluntary for eligible individuals. Many WPC pilots used street or shelter-based outreach to identify eligible enrollees.4 Other strategies used to identify pilot enrollees included referrals from health care facilities, health plan eligibility lists, and predictive modeling based on program criteria.

WPC pilot beneficiaries received care coordination and other services not covered by Medi-Cal to address medical, behavioral health, and social needs. All pilots were required to provide care coordination services, but pilots also offered a variety of other services tailored to local needs and available resources. Services offered by WPC pilots included housing-related services, employment assistance, short-term residential care for individuals experiencing homelessness (referred to as “medical respite”), and sobering centers. Given the high need for housing support, pilots commonly provided housing-related services, including housing navigation (to help identify and secure affordable housing), tenancy supports (e.g., security deposit and first month’s rent), as well as landlord incentives and coaching. Other WPC service examples included providing linkages to health, mental health, and substance use disorder services through medical respite, peer support specialists, mobile teams, or service integration teams.

The state’s Section 1115 waiver authorized up to $3 billion in federal and state Medicaid funds over five years for the WPC pilot. For each demonstration year, $300 million was made available in federal financial participation to fund the WPC pilots. The non-federal share was financed through local funds from participating government agencies (also referred to as “intergovernmental transfers” or IGTs). Each WPC pilot had an annual budget and could draw down funds for eligible activities including infrastructure development, data collection, and services/interventions as well as other outcome-based incentive payments. WPC pilots reimbursed for services on a fee-for-service (FFS) (i.e., per service or encounter) basis or using a per-member-per-month (PMPM) bundle.5 In the early stages, pilots were reimbursed for application submission and reporting baseline data, while subsequent years were oriented toward providing services, achieving proposed metrics, and providing incentive payments.

Pilots were required to submit mid-year and annual reports detailing spending and outcome metrics, including NCQA and HEDIS measures as well as county and population-specific measures. The state is also subject to independent evaluation requirements under its Section 1115 waiver. Findings from the state’s interim independent evaluation of the WPC program are discussed in more detail in the section that follows.

What Can We Learn from WPC?

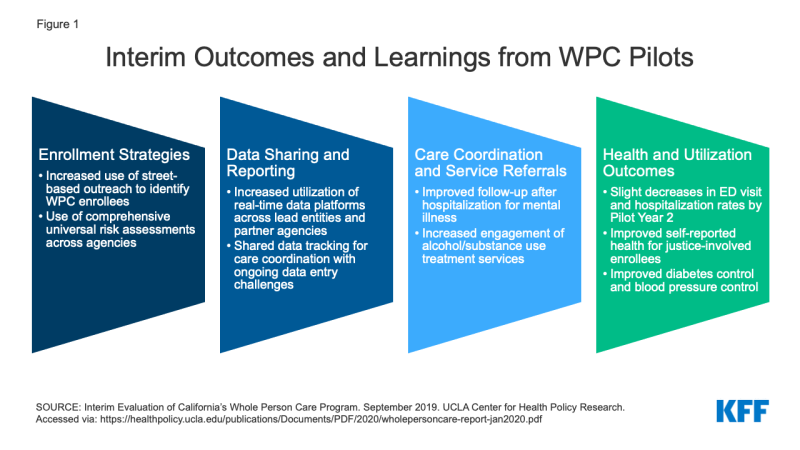

A variety of strategies resulted in the enrollment of more than more than 108,000 unique individuals into WPC between January 2017 and December 2018 (PY 2 and PY 3).6 To identify and enroll eligible individuals, WPC pilots used administrative and electronic medical record data, referrals from partners (managed care plans, health care providers, and clinics), and warm hand-offs from social services agencies. To facilitate referrals into the program, some WPC pilots developed formal contracts with community partners. Pilots also used street- and shelter-based outreach to identify people eligible for but not enrolled in Medi-Cal. To identify the appropriate interventions for enrollees, some pilots developed universal risk assessment tools (used across partner agencies) to stratify client acuity (or level of need) across multiple domains (e.g., health and housing status). To address eligibility gaps in Medi-Cal (also referred to as “churn”), WPC pilots proactively monitored eligibility and renewal dates.7 Nearly all pilots identified low beneficiary engagement – or willingness to enroll and participate in services – as a barrier and stressed the importance of using a “relationship-based” approach to engage medically and socially complex prospective enrollees, as well as a variety of other strategies to foster engagement (e.g., connecting enrollees to immediate benefits, hiring WPC staff with shared lived experience to build trust).8

Data sharing presented challenges for the vast majority of WPC pilots, although capacity increased over time. The majority of pilots developed electronic platforms to facilitate and track care coordination activities (e.g., care plans, encounter notes, and service referrals). Multiple pilots reported participating in health information exchanges and reported increased utilization of real-time data platforms across lead entities and partner agencies over time. Challenges – including duplicative data entry and managing multiple disparate data systems across settings – persisted across most pilots. Other data sharing challenges included concerns around legal risks of data sharing and differing interpretations of laws and regulations involving patient privacy and confidentiality. To address data sharing concerns, some pilots developed universal consent forms to facilitate the release of information across WPC partner organizations, while others developed consent forms to allow for the targeted release of specific data, allowing enrollees to opt out of sharing certain information (e.g., mental health history and HIV test results).9

Pilots reported success with introducing new care coordination processes and using data systems/sharing to support care coordination activities. Care coordination services were frequently provided by non-clinical staff (under supervision of clinical staff) including community health workers (CHWs), and most pilots reported employing care coordinators with shared lived experience. Many pilots reported using a single dedicated care coordinator who followed enrollees across all WPC-participating care settings. Nearly all pilots reported the most common mode of communication between care coordinators and enrollees was in-person. All pilots reported using “active” referral strategies, including helping enrollees schedule appointments, accompanying enrollees to appointments, assisting with transportation, and following up with enrollees after appointments. Challenges common to care coordination included limited availability and/or accessibility of services for referrals. This was especially true for housing needs, where barriers included long wait times for permanent housing, limited housing options available, and poor housing quality.

WPC pilots demonstrated improvements in select health utilization and outcomes, care coordination, and delivery of housing services. The interim evaluation used pilot-reported metrics and Medi-Cal data to determine whether WPC led to better care and better health in the first three years. Analyses included comparison of selected Medi-Cal metrics before and after WPC implementation for WPC enrollees and a control group of Medi-Cal enrollees with similar characteristics. Interim evaluation data showed WPC pilots improved rates of follow-up after hospitalization for mental illness, initiation and engagement in alcohol and drug dependence treatment, and timely provision of comprehensive care plans and suicide risk assessments. The interim evaluation found that emergency department (ED) visit rates from WPC Pilot Year 1 to Pilot Year 2 decreased by 19% for WPC enrollees and 8% for the control group, a significantly larger decrease for the WPC enrollees, although analysis of pre-WPC enrollment compared to post-enrollment ED visit rates found no difference for both groups.10 While adjusted trends of all-cause readmissions did not show a reduction in either group, rates of all-cause readmissions declined from year 1 to year 2 (this decline was greater among WPC enrollees compared to the control group). The interim evaluation also found improvement in health outcomes metrics, including self-reported overall and emotional health and diabetes and blood pressure control. Nearly half of all pilot enrollees were homeless across target populations. The interim evaluation showed success in delivery of housing services and in the receipt of supportive housing, but challenges related to adequate housing supply and direct funding to provide housing. Recent analyses found the COVID-19 pandemic impacted WPC pilots in a variety of ways, but pilots were able to capitalize on existing WPC infrastructure and leverage/coordinate with other COVID-19 response activities. The final evaluation will assess the role of WPC in reducing costs for pilot enrollees and the Medi-Cal program overall, whether care coordination and partnerships were sustained beyond the demonstration, and any differences in interventions/services by target population and pilot site to help identify which services may improve outcomes.

What is Next for WPC and CalAIM?

Under CalAIM, the state will move beyond county pilots to standardize and incorporate services offered by WPC statewide through Medi-Cal managed care plans. CalAIM, which launched in January 2022, seeks to take the state’s whole person care approach statewide, with a central focus on improving health and reducing health disparities and inequities.11 CalAIM adds new programs and reforms existing programs.12 The CalAIM demonstration and its various components are authorized under Section 1115, Section 1915(b), and through state plan amendments. The three stated goals of CalAIM13 are as follows:

- Identify and manage member risk and need through whole person care approaches and addressing SDOH.

- Improve quality outcomes, reduce health disparities, and drive delivery system transformation and innovation through value-based initiatives, modernization of systems, and payment reform.

- Move Medi-Cal to a more consistent and seamless system by reducing complexity and increasing flexibility.

Under CalAIM, Medi-Cal managed care plans will provide Enhanced Care Management (ECM) and Community Supports to targeted high-need beneficiaries. These services will be provided through contracts with community-based providers including organizations that participated in WPC.14 With the launch of ECM and Community Supports, DHCS will sunset the WPC pilots and the Health Homes program.15 Although the state has indicated many WPC enrollees will automatically transition to receiving ECM and Community Supports (many of which the state says may be equivalent to services received under WPC), some WPC enrollees will not transition to receiving these services, and some individuals may lose access to certain services they received under WPC.16 ECM and Community Supports (described in detail in the box below) will only be available to Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in managed care plans, and managed care plans will have discretion over which Community Supports to cover.

Key New Services Offered Under CalAIM

Enhanced Care Management Benefit: The new enhanced care management benefit includes care coordination and comprehensive care management services to address the clinical, behavioral, and social needs of Medi-Cal enrollees with complex needs. Managed care plans will contract with community-based entities (e.g., county agencies, FQHCs, PCPs, CMHCs) to provide care management services.17 DHCS has identified populations of focus for the new ECM benefit (e.g., individuals experiencing homelessness, high utilizers, and adults with serious mental illness or substance use disorders) while managed care plans will be able to add to this list.18 Every beneficiary enrolled in ECM will have a dedicated care manager.

Community Supports: Community Supports (also referred to as “in lieu-of services” (ILOS)) will address social drivers of health.19 These services build on and scale existing work from WPC pilots, Health Homes, and home and community-based services (HCBS) waivers. DHCS has identified 14 Community Supports.20 Services will be delivered through community providers and integrated with ECM. Examples include housing navigation services, recuperative care (medical respite), environmental accessibility adaptations, medically tailored meals, and sobering centers. These services will substitute for certain medical services (e.g., emergency department visits, inpatient hospital care, or nursey facility services) covered by Medi-Cal. The state is encouraging (but not requiring) managed care plans to offer as many of the 14 Community Supports as possible. Most of the Community Supports have been authorized as “ILOS” under Section 1915(b) waiver authority.21 Although “Special Terms and Conditions” (STCs) are not a typical feature of 1915(b) waiver approvals, CMS imposed extensive STCs in connection with the state’s 1915(b) approval. The STCs impose documentation and reporting requirements on both managed care plans and the state Medicaid agency as CMS aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the ILOS and their impact on Medicaid beneficiaries.

Under Section 1115, CMS authorized $1.44 billion in one-time funding to assist with transitioning the WPC pilots and Health Homes programs from Medi-Cal 2020 to CalAIM. “Providing Access and Transforming Health” (PATH) will provide transitional funding to support continuity of services and maintain and support provider and community-based organization capacity. One goal of PATH will be to help ensure Medi-Cal enrollees have continuous access to benefits and services provided previously through WPC pilots as these services and activities are integrated into managed care plans. The funding may not be used to initiate new services but is supposed to ensure continuity for services that correspond to Community Supports managed care plan choose to offer.22 A portion of PATH funds will be used to support justice-involved individuals by sustaining pre- and post-release services provided through WPC pilots and by supporting certain pre-release application planning and IT investments for justice-involved activities.

In addition to incorporating services offered by WPC pilots statewide, the state is planning to undertake a host of other behavioral health reforms under CalAIM. For example, the state plans to integrate the administration and financing of specialty mental health and SUD services under a single state/county contract. The goal is to improve outcomes for enrollees through more coordinated treatment and to allow providers to respond in a more patient-centered way. The state also plans to improve coordination of mental health care between Medi-Cal managed care plans (managing non-specialty mental health services) and county-operated mental health (managing specialty mental health services and SUD treatment). Distinct from these efforts, CalAIM also includes a plan to test the full integration of physical health, behavioral health, and oral health under one contracted managed care entity.

Looking Ahead

As mental illnesses and substance use disorder have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, many states are building on and developing initiatives to address behavioral health issues in Medicaid. States are expanding benefits such as community-based mobile crisis intervention services and screening, expanding the use of telehealth for behavioral health, and using managed care organizations to deliver services. In addition to California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Montana, and Washington are advancing broad behavioral health initiatives spanning many areas. Key lessons from California to date show that such initiatives require integrated data systems, adequate funding streams, and multi-sector provider partnerships to coordinate services. Going forward, California’s experience in trying to scale the WPC pilots statewide and use managed care authority to broadly deliver a range of additional services will be important to understand and learn from as other states work to improve behavioral health services and address social determinants to enhance health and equity.

Appendix

Endnotes

Two pilots (Small County and Solano County) discontinued their WPC programs as of 12/31/2020.

Organizations eligible to apply as lead agencies as defined by the state included county or city agencies, certain designated public hospitals, federally recognized tribes or tribal health programs, or a consortium of these entities.

Letter of extension approval for California Medi-Cal 2020 Demonstration. December 2020. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Expenditure Authority. Accessed via: https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ca/ca-medi-cal-2020-ca.pdf

Pourat P, O’Masta, B, Haley LA, and Chuang E. A Snapshot of California’s Whole Person Care Pilot Program: Implementation Strategies and Enrollees. May 2021. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. Accessed via: https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/publications/Documents/PDF/2021/wholepersoncare-policybrief-may2021.pdf

For example, FFS payments might be made for discrete services including mobile clinic visits, housing transition services, medical respite, transportation, or care coordination. PMPM bundled payments might be made for one or more services and/or activities including comprehensive case management, housing support services, mobile outreach and engagement, or long-term care diversion. DHCS may allow pilots to rollover unspent funds from one year to the next.

Pourat N, Chuang E, Chen X, O’Masta B, Haley LA, Lu C, Huynh MP, Albertson E, and Huerta DM. Interim Evaluation of California’s Whole Person Care (WPC) Program. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, September 2019. Accessed via: https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/publications/Documents/PDF/2020/wholepersoncare-report-jan2020.pdf

Ibid 6.

Chuang E, Pourat N, Haley LA, O'Masta B, Albertson E, and Lu C. Integrating Health And Human Services In California's Whole Person Care Medicaid 1115 Waiver Demonstration. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020 Apr;39(4):639-648. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01617. PMID: 32250689. Accessed via: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01617

Ibid 8.

The interim evaluation used difference-in-difference methodology to compare WPC enrollees to the Medi-Cal enrollee control group between a baseline period (pre-WPC enrollment) and an enrollment period (including data from one year after WPC Year 1 and two years after WPC enrollment). The analysis found no significant change for either group for adjusted trends in emergency department (ED) visit rates and a significant increase in hospitalizations for WPC enrollees compared to the control group. However, the analysis found a decrease in ED and hospitalization rates for both groups from the first to the second years of WPC enrollment. Emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and all-cause readmission for WPC enrollees were rising prior to WPC enrollment and continued to increase in the first year of pilot enrollment (reflecting successful enrollment of high utilizers into the pilot), before declining overall in the second program year.

CalAIM builds on existing infrastructure for the 25 WPC pilots, and counties that did not already have WPC pilots in place were able to apply for additional funding in 2020 to initiate WPC-like pilot capacity. All of the 33 counties that applied for the $20 million one-time funding were approved. Accessed via: https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/Documents/MCQMD/WPC_Documents/20M-One-Time-Funding-10-18-19.pdf

CalAIM Explained: Overview of New Programs and Key Changes. October 2021. California Health Care Foundation. Accessed via: https://www.chcf.org/publication/calaim-explained-overview-new-programs-key-changes/

CalAIM: Our Journey to a Healthier California for All. Department of Health Care Services. Accessed via: https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/CalAIM/Pages/calaim.aspx

Ibid 4.

In 2018, DHCS launched the Health Homes Program (HHP). The HHP serves eligible Medi-Cal managed care plan Members with complex medical needs and chronic conditions who may benefit from intensive care management and coordination. Health plans are required to automatically authorize all HHP Members for ECM and reassess within six months to determine if they still benefit from ECM-level care coordination. Health plans must also appropriately transition eligible HHP Members to applicable Community Supports that the health plan elects to offer. Accessed via: https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/Documents/MCQMD/WPC-and-HHP-Transition-Public-Webinar-9-21-21.pdf

Ibid 15.

Ibid 16.

California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM) Enhanced Care Management. Department of Health Care Services. Accessed via: https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/CalAIM/Documents/CalAIM-ECM-a11y.pdf

“In-lieu-of” services are a substitute for covered services and may qualify as a covered service for the purposes of capitation rate setting, as long as the state determines in-lieu-of services are medically appropriate and cost effective. Enrollees are not required to use the alternative service or setting but may choose to do so. Approved in-lieu-of services are authorized and identified in MCO contracts. Costs associated with in-lieu-of services may be included in the numerator of the medical loss ratio (MLR) and are taken into account when developing capitation rates.

Ibid 18.

The Section 1115 demonstration provides separate authority for short-term post hospitalization housing and recuperative care services (delivered by managed care plans).

Funding will be available where there is a current commitment from the managed care plan that it will elect to offer the service by January 1, 2024.