Who are the Direct Care Workers Providing Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS)?

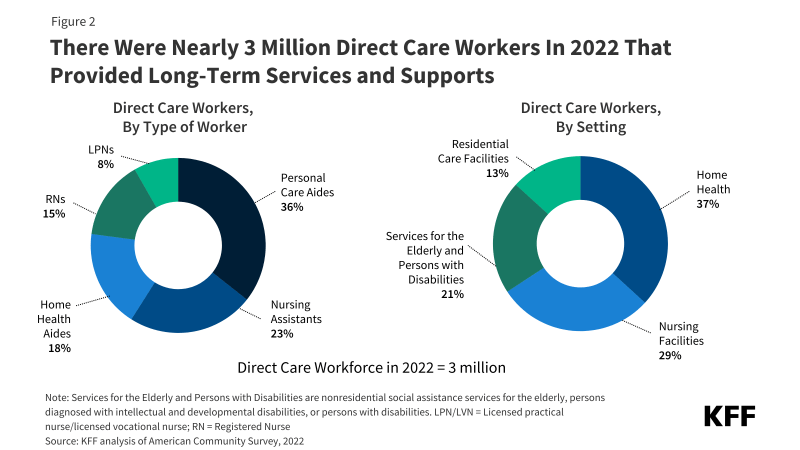

More than 6 million people use paid long-term services and supports (LTSS) delivered in home and community-based settings and more than 2 million people use LTSS delivered in institutional settings, according to CBO estimates. LTSS encompass the broad range of paid and unpaid medical and personal care services that assist with activities of daily living (such as eating, bathing, and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (such as preparing meals, managing medication, and housekeeping). The 8 million people using LTSS only includes people requiring ongoing or maintenance therapy. Many others use similar services on a shorter-term or intermittent basis, such as care provided through the Medicare home health and skilled nursing facility benefits. Direct care workers play a pivotal role in providing these services. They perform demanding, high-stress work for low wages and often no benefits.

This analysis uses the 2022 American Community Survey to provide an overview of demographic characteristics, wages, and health insurance coverage of direct care workers, which include home health aides, personal care aides, nursing assistants, licensed practical nurses (LPNs), and registered nurses (RNs). It focuses in particular on direct care workers in nursing facilities, residential care facilities, and home health as well as those that provide services or work in settings that provide nonresidential services for older adults and younger adults with disabilities (see Methods). In doing so, we examine the direct care workforce broadly and differences across job classifications and settings of work. Key takeaways include:

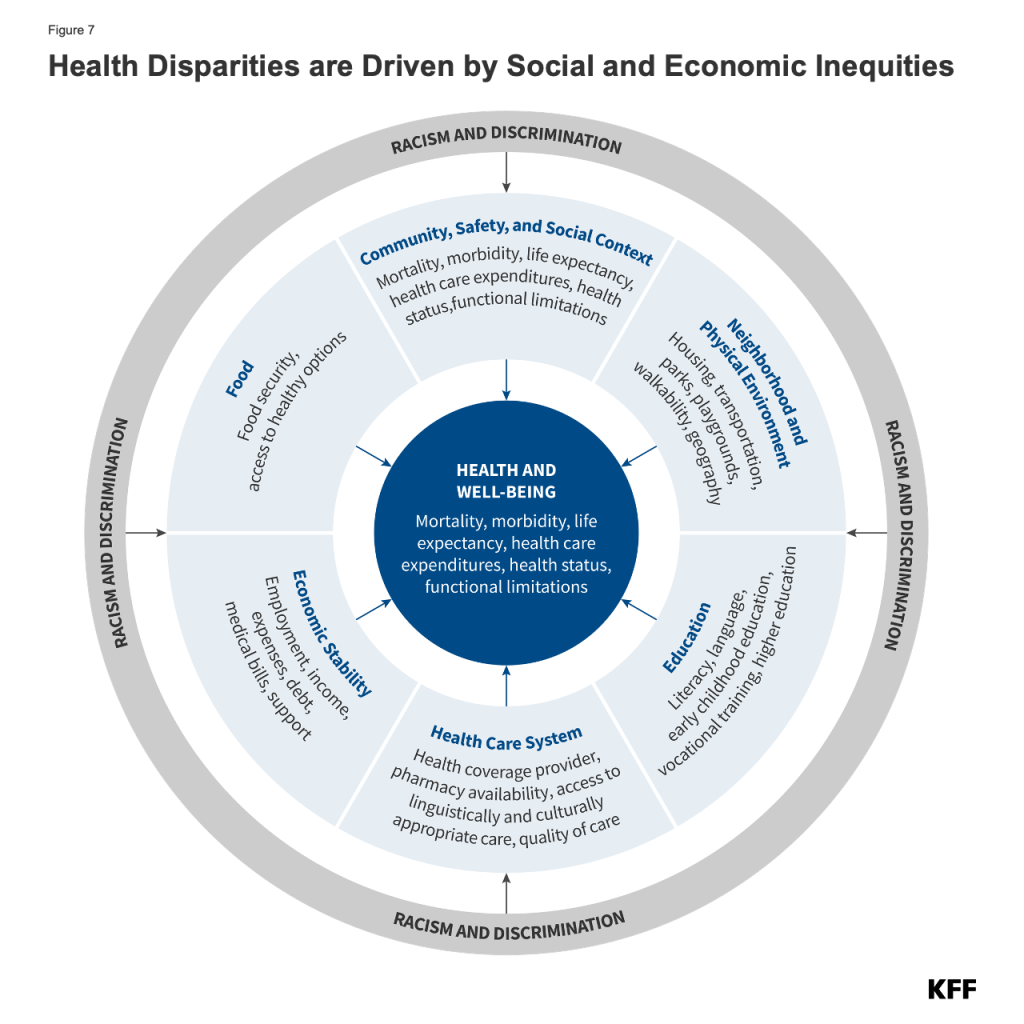

- There are nearly 3 million direct care workers who are predominantly female (87%) and low-wage (65%); over one-quarter are Black (28%) and over four in ten are 50 years old or more (41%) (Figure 1).

- Direct care workers work across a variety of settings and include personal care aides, nursing assistants, home health aides, LPNs, and RNs (Figure 2).

- Home health aides, personal care aides, and nursing assistants (collectively, “aides”) and LPNs are more likely to be under 35, Black or Hispanic, low-wage workers, uninsured, or covered by Medicaid when compared with RNs (Figure 3).

- Nursing facilities and residential care facilities have higher shares of nurses (LPNs and RNs) when compared to home health settings and services for older adults and younger adults with disabilities (collectively, “home and community-based settings”) (Figure 4).

- Direct care workers in home and community-based settings are more likely to be noncitizens and work part-time when compared to those in nursing facilities and other residential care settings (Figure 5).

There have been longstanding challenges finding enough workers to provide LTSS for people who need such services, and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated those issues considerably. In a 50-state survey of officials administering Medicaid HCBS programs, nearly all responding states reported they were experiencing shortages of direct support professionals, personal care attendants, and/or home health aides. The adequacy of staffing in nursing facilities has also been a longstanding issue.

In response to workforce issues, the federal and state governments have taken action to support direct care workers. Section 9817 of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provided states with an additional 10 percentage points of federal funding for their Medicaid HCBS expenditures that occurred between April 1, 2021, and March 31, 2022. States were required to reinvest the additional federal funding in Medicaid HCBS, resulting in an estimated $37 billion of new HCBS funding. As of December 31, 2023, the number one use of the ARPA funds—accounting for more than $26 billion of the planned $37 billion in new funding—was for workforce recruitment and retention. The second largest use (an additional $4 billion) was for workforce training. Other uses of funding include quality improvement activities and reducing or eliminating HCBS waiting lists.

The Biden-Harris Administration finalized two rules aimed at addressing shortages of direct care workers: (1) the first-ever requirements for nurse staffing levels in nursing facilities, and (2) a rule governing access to Medicaid services with several provisions to strengthen the HCBS workforce, including requiring states to spend least 80% of total Medicaid payments for certain HCBS on compensation for direct care workers, a provision that will not take effect until 2029. Many states have adopted payment rate increases for HCBS providers and nursing facilities with the goal of boosting staffing levels, as reported to KFF in a 2023 survey. Vice President Harris also recently put forth a proposal that would establish a new Medicare home care benefit, among other changes. Although the proposal does not yet have specifics, it proposes improvements for care workers via access to better wages.

In 2022, there were nearly 3 million direct care workers who provided LTSS to people ages 65 and older and people under 65 with disabilities. These workers were predominantly female (87%) and low-wage (65%); over one-quarter were Black (28%) and over four in ten were age 50+ (41%) (Figure 1). Nearly one in three were part-time workers, and about one in ten were noncitizens, uninsured, and/or lived in rural areas. These demographic characteristics are all somewhat more common among direct care workers than among other working adults (Appendix Table 1).

Box 1: Who Are Direct Care Workers and Where Do They Work?

By Type of Worker:

Home Health Aides: Home health aides assist older adults and people with disabilities living at home with medical care. They may help with checking vital signs, assist with medical equipment, and help with administering medication. They may also help with activities of daily living (ADLs), which include eating, bathing, dressing, assisting with walking/exercise, and using the bathroom.

Personal Care Aides: Personal care aides assist older adults and people with disabilities living at home with ADLs. Personal care aides also help with instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), such as grocery shopping, meal preparation, and managing medications.

Nursing Assistants: Nursing assistants, or certified nursing assistants (CNAs), typically work in nursing homes and assist residents with ADLs. All CNAs must have completed a nurse aide training and competency evaluation program within 4 months of their employment. They must also pursue continuing education each year.

Licensed Practical Nurses (LPN): LPNs provide care under the direction of a registered nurse (RN). Together, RNs and LPNs make sure someone’s plan of care is being followed and their needs are being met. LPNs typically have one year of training.

Registered Nurses (RN): RNs are responsible for the overall delivery of care and assess overall health care needs. RNs are typically required to have between two and six years of education.

By Setting of Care:

Nursing Facilities: Nursing facilities are residential settings that provide round-the-clock nursing and personal care to residents who either need short-term rehabilitation following a hospitalization or injury or long-term care to residents with chronic medical and/or mental health conditions requiring access to 24-hour skilled care and assistance with ADLs or personal care.

Residential Care Facilities: These settings include residential settings that serve individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, mental illness, or substance use disorder. These settings also include establishments that provide residential and personal care services for older adults or younger adults with disabilities who are unable to fully care for themselves. These settings can include assisted living facilities, continuing care retirement communities, and group homes for adults with disabilities. The care typically includes room, board, supervision, and assistance with activities of daily living.

Home Health: Home health agencies are organizations that provide skilled rehabilitative or post-acute care as well as long-term personal care for patients. The same skilled services provided by skilled nursing facilities, such as nursing, occupational therapy, and physical therapy, are instead provided in the home, along with assistance with ADLs and IADLs.

Services for the Elderly and Persons with Disabilities: These are services or settings that provide nonresidential, social assistance services for older adults and younger adults with disabilities. These establishments typically focus on the welfare of these individuals in such areas as day care, non-medical home care or homemaker services, social activities, group support, and companionship. These services and settings can include adult day care centers, home care services for older adults, and companion services.

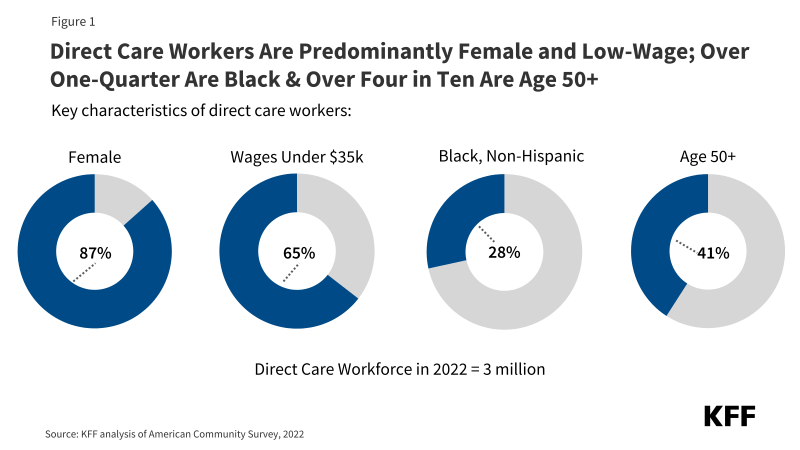

Direct care workers provide care across various settings: 58% worked in home health settings or provided nonresidential services for seniors and people with disabilities (collectively, “home and community-based services” or “HCBS”), 29% worked in nursing facilities, and the remaining 13% worked in residential care facilities (Figure 2). Nursing facilities are the most medically-oriented institutional settings, providing both short-term skilled nursing and long-term maintenance care services. Residential care facilities include a variety of settings – some institutional and some community-based – and are, as a group, less institutionalized than nursing facilities. HCBS are provided in people’s homes and other community-based settings (Box 1).

Over three-quarters (77%) of direct care workers were personal care aides, nursing assistants, or home health aides (collectively “aides”) and the remaining quarter (23%) were registered nurses (RNs) or licensed practical nurses (LPNs) (Figure 2). Direct care worker responsibilities vary, with some workers primarily providing personal care services, some providing primarily medical care, and some providing a mix of both. Aides tend to provide mostly personal care services whereas RNs provide mostly medical care, and LPNs provide both types of services (Box 1). The educational requirements for LPNs and, especially, RNs, are greater than the requirements for aides on account of the more medical nature of their duties.

Compared with registered nurses, higher percentages of aides and LPNs are younger, Black or Hispanic, low wage, and covered by Medicaid or uninsured (Figure 3). Nearly one in three aides (31%) and over one in four LPNs (27%) are under 35 years old, compared with just one in five RNs (20%). Over half of all aides (52%) and nearly four in ten LPNs (39%) are Black or Hispanic, compared to just 25% of RNs. RNs are the highest paid direct care workers and aides are the lowest-paid direct care workers, with over three-quarters (76%) of aides reporting wages under $35,000. In comparison, just one-fifth (21%) of RNs report wages of less than $35,000. LPNs’ wages are higher than those of aides but lower than those of RNs. The differences in wages are likely attributable, at least in part, to the fact that the educational requirements are most rigorous for RNs and least rigorous for aides. Aides are also more likely than nurses to work part-time, likely another contributing factor to the wage discrepancies (Appendix Table 1). Aides are twice as likely to be uninsured compared with RNs (12% vs 6%) and four times as likely to be covered by Medicaid (35% vs 9%). LPNs are nearly twice as likely as RNs to be uninsured (11% vs 6%) or be covered by Medicaid (16% vs 9%).

Nursing facilities and residential care facilities have higher shares of nurses compared to home and community-based settings (Figure 4). The percentage of direct care workers who are RNs or LPNs is 43% in nursing facilities, 21% in residential care facilities, and 14% in home and community-based settings. The Biden-Harris Administration released a rule that creates new requirements for nurse staffing levels in nursing facilities, including minimum levels for nurse aides and registered nurses. This rule was highly anticipated as it would create the first-ever federal minimum staffing levels, though even prior to the staffing rule, many states had their own minimum staffing levels. In contrast, a new rule on access to Medicaid services includes several requirements regarding the adequacy of states’ payments for direct care workers in home and community-based settings, but does not establish any minimum staffing levels for such settings.

Direct care workers that work in home and community-based settings are significantly more likely to be noncitizens, work part-time, and have lower wages when compared to those in nursing facilities and other residential care settings (Figure 5 and Appendix Table 1). Among direct care workers in home and community-based settings, 12% are noncitizens compared with 8% in residential care facilities and 6% in nursing facilities. Noncitizens include those who are lawfully present as well as those who are undocumented, though the majority of noncitizen immigrants are lawfully present. Part-time work is also more common among workers in home and community-based settings, with 40% of workers working part-time compared with 22% of nursing facility workers and 24% of residential care facility workers. Direct care workers overall are more likely to be part-time workers than all adult workers (32% vs 16%), which may be part of the reason they are more likely to have wages under $35,000 (64% vs. 38%) (Appendix Table 1). Low wages among direct care workers broadly are a key driver in the high turnover in the workforce, which has spurred action among federal and state policymakers. The Biden-Harris administration finalized a rule aimed at ensuring access to Medicaid services, which included a provision that requires states to spend least 80% of total payments for certain HCBS on compensation for direct care workers. Most states have also increased payments to direct care workers to increase the supply of HCBS workers, though some of those states have indicated that some of those increases are temporary.

Both 2024 presidential candidates have addressed direct care workforce shortages in their party platforms, but questions remain about how the shortages would be addressed. The Republican platform proposals address disincentives that contribute to workforce shortages, but it is unclear what policies a Republican Administration would put forth to achieve those goals. On October 8, 2024, Vice President Harris put forth a proposal that would establish a new Medicare home care benefit, among other changes. Although the proposal is not fully specified, it proposes to lift up care workers by providing access to better wages. If enacted, the Harris proposal would be the first major expansion of Medicare since the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 that added a prescription drug benefit to the program. Many policy details would have to be worked out as the proposal wound its way through Congress, including questions about eligibility, benefit design, financing, and workforce shortages.

Methods

This analysis is based on KFF analysis of the 2022 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-year file. The ACS includes a 1% sample of the US population, and the subset of direct care workers used here includes over 26,000 observations. Direct care workers are those who fall into the following occupation codes: Registered nurses (3255); Licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses (3500); Home health aides (3601); Personal care aides (3602); and Nursing assistants (3603). Home health aides, personal care aides, and nursing assistants are collapsed into “Aides” in parts of this analysis. This analysis only includes those who work in the following industries: Home Health Care (8170), Nursing Care Facilities (8270), Residential Care Facilities (8290), and Individual and Family Services (8370). Home health care and individual and family services are collapsed into “HCBS” for parts of this analysis.

These industries capture the majority of workers providing long-term health services. They exclude some workers who may be providing ongoing non-health social services to individuals. The ACS asks respondents about their health insurance coverage at the time of the survey. Respondents may report having more than one type of coverage; however, individuals are sorted into only one category of insurance coverage.

We define the direct care workforce as all individuals who earned at least $1,000 during the year and indicated that their job was in both the long term care industry and occupation codes listed above.

Notably, the ACS does not include unpaid LTC caregivers, such as relatives and friends, who actually provide the majority of community-based long-term services and supports in the US. A limitation of federal surveys broadly, including ACS, is the likely underrepresentation of noncitizens, particularly recent and undocumented immigrants.