The U.S. Government and Multilateral Global Health Engagement: 5 Key Facts

Global health donors, such as the U.S., provide funding and other support primarily through two types of channels: bilateral (i.e., country-to-country) and/or multilateral (i.e., multi-country, pooled support often directed through an international organization). Donors make different choices about the distribution of their global health support between these two mechanisms, and these choices may change over time due to political, technical, or other considerations.1 While the U.S. has decidedly been a bilateral donor to global health (channeling 81% of current global health assistance bilaterally), it has helped to found, and serves as a key donor to, several major multilateral health organizations. These include some of the first international health organizations, such as the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) in 1902 and the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1948, and newer partnerships, such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi) in 2000 and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund) in 2002. These multilateral organizations have contributed significantly to improvements in global health2 and, in some cases, serve as key components of the U.S. global health response. This response includes financing, governance, oversight, and technical assistance.

Multilateral global health organizations are those jointly supported by multiple governments and, often, other partners (versus bilateral efforts, which are carried out on a country-to-country basis). Examples include:

- health-focused or health-emphasizing specialty agencies of the United Nations (U.N.), such as PAHO, WHO, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the U.N. Population Fund (UNFPA), and the U.N. Children’s Fund (UNICEF); and

- international financing mechanisms for global health, such as Gavi, the Global Fund, and the TB Drug Facility (at the Stop TB Partnership), which pool and direct resources from multiple public and private donors for specific health causes.

Still, U.S. support for multilateral institutions has fluctuated over time, reflecting, in part, changing U.S. leadership views on the relative value of bilateralism versus multilateralism. Following a period of increasing U.S. support for multilaterals, particularly during the Obama Administration, the Trump Administration has signaled skepticism about such engagement, requesting less funding for international organizations (including multilateral health organizations) and withdrawing from several multilateral agreements.3 Even so, our polling shows that most Americans – in fact, an increasing percentage – believe the U.S. should be working in coordination with others on international health efforts (see Americans’ Views on the U.S. Role in Global Health).

With ongoing questions about future U.S. support for multilateral health efforts as well as important markers on the near horizon, including donor replenishment conferences for both the Global Fund and Gavi within the next two years, this brief highlights five key facts about U.S. engagement with multilateral global health organizations. It focuses on those organizations to which Congress specifically directs funding (there are eight, including five U.N. entities; see Box 1) but is not meant to be an exhaustive review of all multilateral health initiatives in which the U.S. may participate.

| Box 1: Multilateral Health Organizations Supported by the U.S.* |

| U.N. Agencies |

|

| Non-U.N. Financing Mechanisms |

NOTE: * indicates includes those organizations to which Congress specifically directs funding.4 Multilateral global health initiatives the U.S. supports without direct congressional appropriations are not covered in this brief, including the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI); the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA); and the Global Financing Facility (GFF), among others. Such organizations may receive funding determined at the agency level. |

1. U.S. multilateral funding for health has grown over time but, mirroring overall trends, flattened more recently.

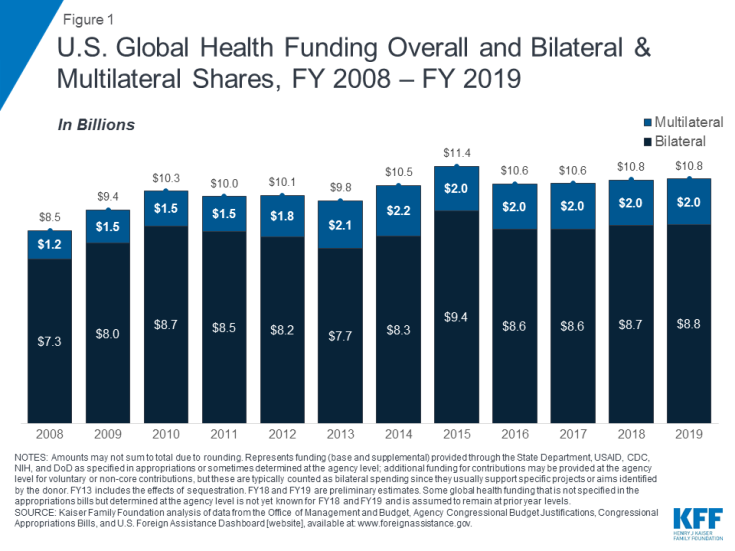

The amount of U.S. global health funding directed multilaterally varies each year but has generally grown over time, both in amount and as a share of the U.S. global health budget. The U.S provided initial support for Gavi (launched in 2000) and the Global Fund (launched in 2002), while continuing its support for U.N. health agencies, and U.S. funding to multilateral global health organizations has generally increased over time since then. From FY 2008 through FY 2018, U.S. multilateral health funding5 increased from $1.2 billion to $2.0 billion, with a peak of $2.2 billion in FY 2014 (see Figure 1). This represents funding specified by Congress in appropriations for contributions to the five U.N. entities identified in Box 1 – provided as “regular,” “core,” or “assessed” contributions6 (generally used to support essential functions and operations) and contributions to Gavi, the Global Fund, and the TB Global Drug Facility. More recently, general budget pressures led to a flattening of U.S. global health funding, including for multilateral efforts.

In addition, U.S. agencies at times provide other funding that is not specified by Congress to U.N. entities; these additional contributions are often referred to as “voluntary” or “non-core” contributions and used for specific projects or initiatives the U.S. seeks to support. In some cases these voluntary contributions are quite sizable (see Appendix). For example, in FY 2017, about three-quarters of U.S. contributions to WHO were voluntary, and nearly half of U.S. contributions to UNAIDS were non-core contributions.

As a share of the U.S. global health budget, multilateral funding has also increased over time, rising from 15% in FY 2008 to 19% in FY 2018 (its high point was 21% in 2013 and 2014); see Table 1. This growth in part reflected an increased emphasis placed on multilateral cooperation by the Obama Administration, as well as growing support in Congress.

| Table 1: Bilateral and Multilateral Shares of U.S. Global Health Funding, FY 2008 – FY 2019 | ||||||||||||

| Channel | FY08 | FY09 | FY10 | FY11 | FY12 | FY13 | FY14 | FY15 | FY16 | FY17 | FY18 | FY19 |

| Total ($ in Billions) |

$8.5 | $9.4 | $10.3 | $10.0 | $10.1 | $9.8 | $10.5 | $11.3 | $10.6 | $10.6 | $10.8 | $10.8 |

| Bilateral | 85% | 84% | 85% | 85% | 82% | 79% | 79% | 83% | 81% | 81% | 81% | 81% |

| Multilateral | 15% | 16% | 15% | 15% | 18% | 21% | 21% | 17% | 19% | 19% | 19% | 19% |

| NOTES: Represents funding (base and supplemental) provided through the State Department, USAID, CDC, NIH, and DoD as specified in appropriations or sometimes determined at the agency level; additional funding for contributions may be provided at the agency level for voluntary or non-core contributions, but these are typically counted as bilateral spending since they usually support specific projects or aims identified by the donor. FY13 includes the effects of sequestration. FY18 and FY19 are preliminary estimates. Some global health funding that is not specified in the appropriations bills but determined at the agency level is not yet known for FY18 and FY19 and is assumed to remain at prior year levels. | ||||||||||||

The Trump Administration, however, has called for significant budget cuts to foreign assistance, including for multilateral health programs.7 For FY 2018, the Administration proposed a 24% (or $481 million) cut to multilateral global health funding. This was rejected by Congress, which instead provided a $16 million increase over FY 2017 levels.8 For FY 2019, the Administration requested a 37% cut ($735 million) to multilateral health funding, which, if enacted, would have returned funding to pre-FY 2009 levels and was a steeper proposed cut to multilateral programs than bilateral programs (19%).9 Congress rejected this proposed cut as well.

2. U.S. contributions to multilateral health organizations are significant.

The U.S. provides significant support to a number of multilateral global health organizations (see Appendix). In many cases, the U.S. is the largest, or one of the largest, donors to these organizations. For example, the U.S. is the top contributor to five of the eight organizations: the Global Fund, PAHO, UNAIDS, UNICEF, and WHO.10

However, this is not always the case, and U.S. contributions to multilaterals can change over time. For example, while the U.S. helped to found the United Nations Populations Fund (UNFPA) in 1969 and was a leading supporter for many years, its support has fluctuated significantly over the years, due to ongoing political debates about abortion. Most recently, the Trump Administration determined it would withhold U.S. support to the agency, invoking the Kemp-Kasten Amendment of U.S. law to do so (see KFF’s explainer).11

3. U.S. support for multilateral health organizations often complements its bilateral programs in support of global health goals.

Multilateral initiatives complement U.S. bilateral global health efforts, helping make progress toward U.S. goals in various program areas. In some cases, multilateral support allows the U.S. to reach a larger number of countries; it also may help to leverage additional funding and provide opportunities for improved coordination and technical consultations. For example:

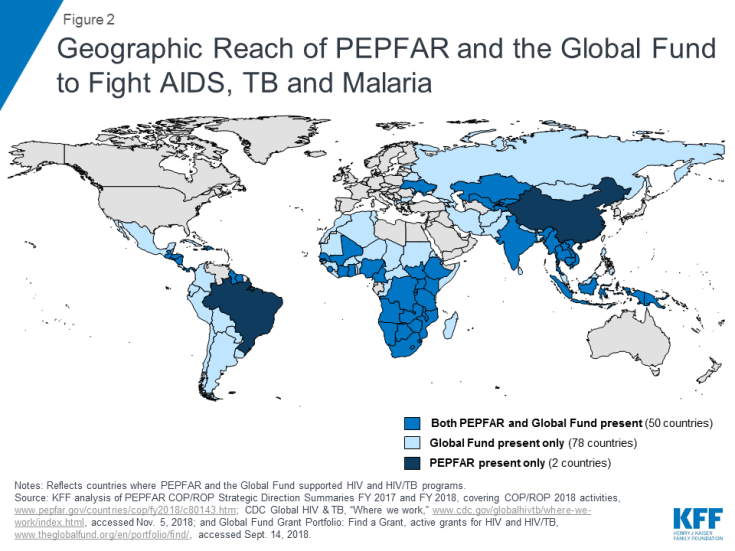

- HIV. While primarily bilateral, U.S. global efforts to fight HIV under the umbrella of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) include multilateral support, primarily through contributions to the Global Fund but also to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). U.S. investments in the Global Fund, in particular, are recognized as the “multilateral arm”12 of PEPFAR. PEPFAR coordinates its bilateral spending and activities in PEPFAR countries with the grants provided to and activities supported in countries by the Global Fund. Furthermore, U.S. contributions to the Global Fund extend the reach of PEPFAR by reaching an additional 78 countries where the PEPFAR bilateral program does not operate (see Figure 2). In addition, since U.S. law requires that the U.S. contribution cannot exceed 33% of total contributions from all donors, the U.S. contribution to the Global Fund leverages other donor contributions. See KFF fact sheet on PEPFAR and the fact sheet on the Global Fund.

- Maternal and child health (MCH). In addition to U.S. bilateral efforts to improve MCH, the U.S. also provides multilateral support for MCH through contributions to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and Gavi. For example, in the area of immunization, UNICEF and Gavi are key U.S. partners in working toward ending preventable child deaths, which is a U.S. priority, and they play a critical role in expanding vaccine access by addressing affordability and vaccine development issues. UNICEF (a U.N. agency aiming to improve the lives of children, particularly the most disadvantaged children, to which the U.S. is the largest donor) is one of the largest purchasers of vaccines and distributes childhood vaccines worldwide, while Gavi (a multilateral financing mechanism aiming to increase access to immunization in poor countries to which the U.S. is one of the largest donors) provides funding to eligible countries to accelerate introduction of new and underused vaccines and strengthen vaccine delivery systems. These global efforts complement U.S. bilateral efforts, where in a subset of countries the U.S. provides technical assistance to immunization programs to strengthen routine immunization systems and identify areas where more equitable vaccine access may be improved. See the KFF fact sheet on global MCH and the KFF fact sheet on Gavi.13

4. U.S. multilateral engagement influences international priorities and contributes to global standard-setting.

The U.S. government shapes multilateral global health efforts not only through funding but also through its participation in governance structures and the development and execution of technical and standard-setting guidance, agreements, plans, and programs:

- Funding. As mentioned above, the U.S. is often the largest or one of the largest donors to multilateral health efforts. Without U.S. core funding, many U.S.-supported multilateral organizations’ essential operations and functions would be jeopardized. Additionally, U.S. funding for “voluntary” or “non-core” contributions is also a key budget component driving global efforts. Further, U.S. policies related to funding can also greatly influence financial support for multilaterals. As mentioned above, the U.S. contribution to the Global Fund leverages other donor contributions, since U.S. law requires that the U.S. contribution cannot exceed 33% of total contributions from all donors.

- Governance. The U.S. government is active in the governance structures that oversee multilateral global health organizations and initiatives, including holding permanent or rotating seats on many of their boards. It currently participates in key governance mechanisms for all of the eight key multilateral health organizations identified (see Table 2). For example, the U.S. government has a permanent Board seat on the Global Fund’s Board and is currently an alternate member of the Gavi Board, and this year, the U.S. again assumed a seat on the WHO Executive Board.

| Table 2: Selected Multilateral Organizations and Initiatives Related to Global Health and Current U.S. Participation in Governance | |

| Organization | Current U.S. Participation in Governance |

| Gavi | |

| Global Fund | |

| PAHO |

member of the Executive Committee19 (rotating seat among member states)

|

| TB Global Drug Facility (at Stop TB Partnership) |

member of the Stop TB Partnership Board (CDC has current seat, 1 of 2 that rotates among technical agencies; USAID has current seat, 1 of 3 for financial donors)

|

| UNAIDS |

member of the Programme Coordinating Board (rotating seat among Western European and Others Group) 20

|

| UNICEF |

permanent member of the Executive Board (since 1948)21

|

| UNFPA |

member of the Executive Board (rotating seat among Western European and Other States)22

|

| WHO |

member of the Executive Board (rotating seat among the Americas region)23

|

| NOTES: As of Jan. 25, 2019. | |

- Technical assistance and standard-setting. The U.S. supports the role of multilaterals in technical guidance and standard-setting plans and programs in several ways. For one, the U.S. government seconds a number of employees to or designates staff to serve as liaisons to these organizations, including to WHO and PAHO.24 The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) run several WHO collaborating centres for various global health issue areas (such as global cancer control, influenza, malaria, reproductive health, and viral hemorrhagic fevers25). U.S. multilateral engagement also influences WHO and other international organizations that set standards related to health, such as essential medicines and recommendations on specific treatment protocols. Lastly, the U.S., as a member-state of WHO, weighs in on global plans to respond to a range of health issues, such as NCDs or various infectious diseases, as they are developed and considered for approval by the larger body.

5. The next two years will reveal much about U.S. commitment to multilateral health engagement.

With several key international meetings and replenishment conferences on the horizon, the next two years will provide a number of opportunities for assessing the level of U.S. commitment to multilateral global health efforts. For example:

- In September, U.N. member states will come together at the High-Level Meeting (HLM) on Universal Health Coverage (UHC) to discuss improving access to and the quality of health care worldwide. However, this has been an area where the U.S. has shown only lukewarm involvement in the past, even as the UHC agenda has been adopted by most countries around the world and is a key component of the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals. U.S. participation in the HLM could either be a moment of change or one in which the U.S. maintains the status quo.

- In October, the Global Fund will hold its replenishment conference for the 2020-2022 period, and in 2020, Gavi will hold its replenishment conference for the 2021-2025 period. In the past, these conferences have provided an opportunity for the U.S. government, including the Administration and Congress, to demonstrate their commitment to these multilateral financing institutions. These upcoming conferences will present a similar opportunity, though in light of recent proposed cuts to the Global Fund and Gavi by the current Administration – cuts that Congress ultimately rejected, there will likely be significant discussion between the Administration and Congress about the levels of funding the U.S. should pledge during the conferences. U.S. actions will be closely observed particularly in the case of the Global Fund replenishment, as the U.S. has always been the leading donor to the Global Fund and has used its contribution to leverage other donor investments in the Global Fund.

It will be important to keep these key facts in mind over the next two years, as discussion and debate over U.S. contributions to these and other multilateral health institutions continue.

Appendix: U.S. Contributions Related to Global Health to Selected Multilateral Organizations, FY 2008 – FY 2019

| Table A: U.S. Contributions Related to Global Health to Selected Multilateral Organizations, FY 2008 – FY 2019 | ||||||||||||

| FY08 | FY09 | FY10 | FY11 | FY12 | FY13 | FY14 | FY15 | FY16 | FY17 | FY18 | FY19 | |

| U.S. Contributions* | ||||||||||||

| Gavi | 71.9 | 75.0 | 78.0 | 89.8 | 130.0 | 138.0 | 175.0 | 200.0 | 235.0 | 275.0 | 290.0 | 290.0 |

| Global Fund | 840.3 | 1000.0 | 1050.0 | 1045.8 | 1300.0 | 1569.0 | 1650.0 | 1350.0 | 1350.0 | 1350.0 | 1350.0 | 1350.0 |

| PAHO (assessed) | 57.9 | 59.1 | 59.8 | 60.5 | 63.1 | 65.7 | 65.7 | 65.7 | 64.5 | 64.3 | 65.3 | 65.3 |

|

TB Global Drug Facility

(at Stop TB Partnership)

|

14.9 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.3 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 13.5 | 15.0 |

| UNAIDS (core) | 34.7 | 40.0 | 43.0 | 42.9 | 45.0 | 42.8 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 45.0 |

| UNFPA (core) | 0.0 | 46.1 | 51.4 | 37.0 | 30.2 | 28.9 | 30.7 | 30.8 | 30.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | — |

| UNICEF (regular)b | 128.0 | 130.0 | 132.3 | 132.3 | 131.8 | 125.2 | 132.0 | 132.0 | 132.5 | 137.5a | 137.5 | 137.5 |

| WHO (assessed) | 101.4 | 106.6 | 106.6 | 109.4 | 109.4 | 109.9 | 109.9 | 113.9 | 112.8 | 111.4 | 112.9 | 112.9 |

| TOTAL** | 1249.1 | 1471.8 | 1536.0 | 1532.7 | 1824.5 | 2093.7 | 2223.3 | 1952.5 | 1985.5 | 1998.2 | 2014.2 | 2015.7 |

| Additional U.S. Contributionsb | ||||||||||||

| PAHO (voluntary) | 6.1 | 6.1 | 2.1 | 6.6 | 23.7 | 12.5 | 3.0 | 22.5 | 13.1 | — | — | — |

| UNAIDS (non-core) | 5.2 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 2.0 | 6.5 | 21.2 | 14.4 | 6.6 | 22.6 | 37.4 | — | — |

| UNFPA (non-core) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 1.4 | 3.6 | 6.9 | 17.8 | 45.0 | 32.6 | 5.8c | — | — |

| WHO (voluntary) | 112.0 | 110.0 | 304.4 | 112.4 | 222.4 | 221.1 | 101.7 | 324.3 | 228.0 | 401.1 | — | — |

| NOTES: FY13 includes the effects of sequestration. FY18 and FY19 are preliminary estimates. Some global health funding that is not specified in the appropriations bills but determined at the agency level is not yet known for FY18 and FY19 and is assumed to remain at prior year levels. — indicates amount is not yet known or set. * indicates represents funding (base and supplemental) provided through the State Department, USAID, CDC, NIH, and DoD as specified in appropriations or sometimes determined at the agency level including for U.S. contributions that are considered “regular,” “core,” or “assessed” contributions, which are usually identified in congressional budget justifications and/or appropriations legislation and related material and specifically directed by Congress. UNFPA amounts reflect funding provided after funding level adjustments due to congressional requirements, including presidential determinations under the Kemp-Kasten amendment, have been applied to appropriated funding levels; the FY19 UNFPA contribution amount is still to be determined. ** indicates the total does not include additional (other resources, non-core, or voluntary) contributions provided at the agency level; these are typically counted as bilateral spending since they usually support specific projects or aims identified by the donor. a includes $5 million in funding designated for female genital mutilation. b indicates that the U.S. also provides additional contributions to UNICEF but that since within this amount it is difficult to identify the portion that is directed to health versus non-health activities, they are not reflected in this table. c indicates funding is due to multi-year agreements. |

||||||||||||