States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019

Managed Care Initiatives

| Key Section Findings |

| Managed care is the predominant delivery system for Medicaid in most states. As of July 1, 2018, among the 39 states with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs), 33 states reported that 75% or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs, a notable increase from the 29 states reporting 75% or more as of July 1, 2017. Although many states still carve-out behavioral health services from MCO contracts, movement to carve-in these services continues – two states in FY 2018 and 11 states in FY 2019 reported BH service carve-ins or implementation of an integrated MCO arrangement. Nearly all states have managed care quality initiatives in place such as pay for performance or capitation withholds.

What to watch:

Tables 4 through 7 include more detail on the populations covered under managed care (Tables 4 and 5), behavioral health services covered under MCOs (Table 6), and managed care quality initiatives (Table 7). |

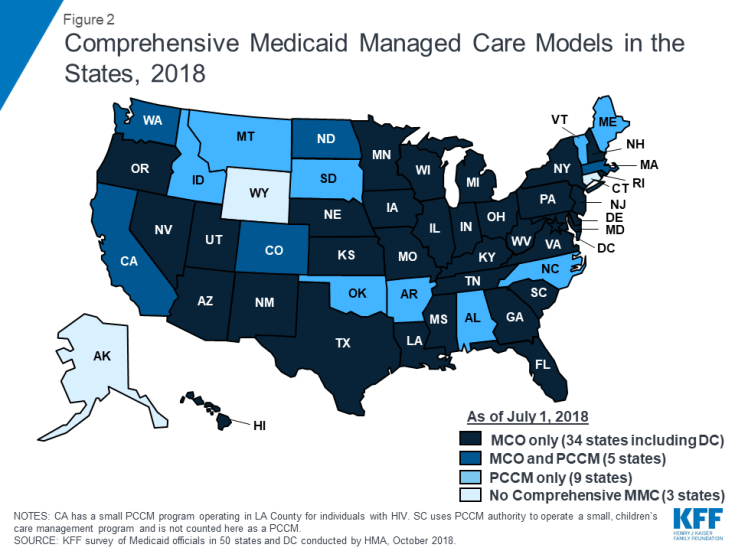

Managed care remains the predominant delivery system for Medicaid in most states. As of July 2018, all states except three – Alaska, Connecticut,1 and Wyoming – had some form of managed care in place, unchanged from July 2017. Compared to the prior year, the number of states contracting with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs) (39 states) also remained unchanged while two fewer states reported operating a Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) program (14 states). PCCM is a managed fee-for-service (FFS) based system in which beneficiaries are enrolled with a primary care provider who is paid a small monthly fee to provide case management services in addition to primary care.

Of the 48 states that operate some form of managed care, five operate both MCOs and a PCCM program while 34 states operate MCOs only and nine states operate PCCM programs only2 (Figure 2 and Table 4). In total, 28 states contracted with one or more PHPs to provide Medicaid benefits including, behavioral health care, dental care, vision care, non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT), or long-term services and supports (LTSS).

The current administration is expected to release revised Medicaid managed care regulations for public comment. Under the previous administration in April 2016, CMS issued a final rule on Medicaid managed care providing a framework of plan standards and requirements designed to improve the quality, performance, and accountability of these programs.3,4 The new rule represented a major revision and modernization of federal regulations in this area. The Trump Administration, however, is expected to release revised Medicaid managed care regulations before the end of CY 2018.5

In advance of releasing revised Medicaid managed care regulations, CMS released an Informational Bulletin6 in June 2017 indicating they would use “enforcement discretion” to work with states on achieving compliance with the new managed care regulations, except for specific areas that “have significant federal fiscal implications.” In this year’s survey, MCO states were asked whether they have asked CMS for flexibility in meeting managed care regulation deadlines. States answering “yes” most frequently reported requesting relief on deadlines related to member services (e.g., grievance and appeals procedures or member handbooks and enrollment requirements) and provider/network requirements (e.g., screening and enrollment of network providers or provider directory requirements).

Populations Covered by Risk-Based Managed Care

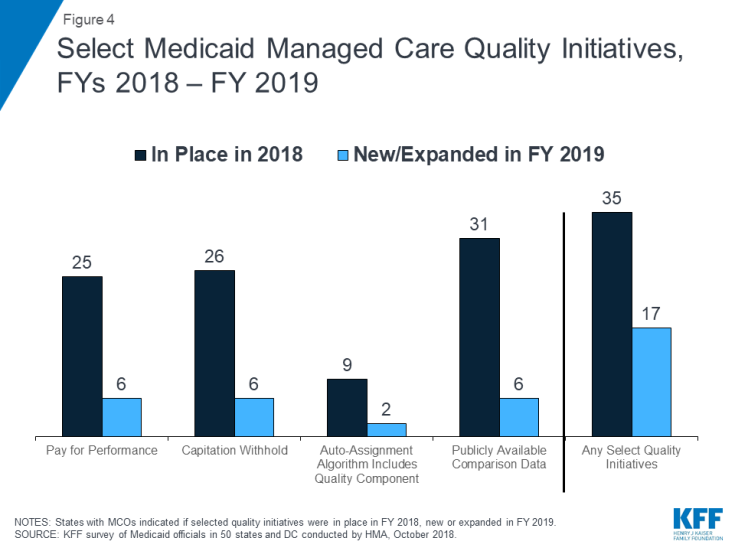

The share of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in MCOs has steadily increased as states have expanded their managed care programs to new regions and new populations and made MCO enrollment mandatory for additional eligibility groups. This year’s survey showed continued notable growth. Among the 39 states with MCOs, 33 states7 reported that 75% or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2018 (up from 29 states in last year’s survey), including nine of the ten states with the largest total Medicaid enrollment. These nine states (California, New York, Texas, Florida, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, and Georgia) account for over half of all Medicaid beneficiaries across the country (Figure 3 and Table 4).8

Children and adults, particularly those enrolled through the ACA Medicaid expansion, are much more likely to be enrolled in an MCO than elderly Medicaid beneficiaries or persons with disabilities. Thirty-five9 of the 39 MCO states reported covering 75% or more of all children through MCOs. Of the 32 states that had implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion as of July 1, 2018, 27 were using MCOs to cover newly eligible adults.10 The large majority of these states (23 states) covered more than 75% of beneficiaries in this group through capitated managed care. New Hampshire reported that most of its ACA expansion adults are enrolled in Qualified Health Plans (with premium assistance, under Section 1115 authority) and only 20% are enrolled in MCOs.11 The state reported, however, that it will end its premium assistance waiver (as of December 31, 2018) and will transition QHP-enrolled members to MCOs. Thirty-one of the 39 MCO states reported covering 75% or more of low-income adults in pre-ACA expansion groups (e.g., parents, pregnant women) through MCOs. In contrast, the elderly and people with disabilities were the group least likely to be covered through managed care contracts, with only 20 of the 39 MCO states reporting coverage of 75% or more such enrollees through MCOs (Figure 3).

Figure 3: MCO Managed Care Penetration Rates for Select Groups of Medicaid Beneficiaries as of July 1, 2018

In states with both MCOs and PCCM programs, MCOs cover a larger share of beneficiaries than PCCM programs in a majority of these states. However, Colorado is an exception: as of July 1, 2018, a majority of Colorado’s enrollees were in the PCCM program, which is the foundation of the state’s “Accountable Care Collaboratives.”

Alaska and Arkansas reported plans to implement an MCO program for the first time in FY 2019. Alaska is contracting with one MCO to serve one geographic area that includes Anchorage and the Mat-Su Valley, and Arkansas will begin making actuarially sound “global payments” (beginning January 1, 2019) to “Provider-led Arkansas Shared Savings Entities” (PASSEs) that will serve Medicaid beneficiaries who have complex behavioral health and intellectual and developmental disabilities service needs. Only one state reported policies that reduced the state’s reliance on the MCO model of managed care: Massachusetts reported that the implementation of its Accountable Care Organization (ACO) program beginning in FY 2018 has resulted in decreased MCO enrollment as MCO enrollees may choose to enroll in ACOs instead.

Populations with Special Needs

For geographic areas where MCOs operate, this year’s survey asked MCO states whether, as of July 1, 2018, certain subpopulations with special needs were enrolled in MCOs for their acute care services on a mandatory or voluntary basis or were always excluded. This year’s survey further grouped subpopulations by dual eligible and by LTSS status (Exhibit 4 and Table 5).

Pregnant women were the group most likely to be enrolled on a mandatory basis while persons with I/DD were among the least likely to be enrolled on mandatory basis. As a group, foster children were most likely to be enrolled on a voluntary basis, although they were enrolled on a mandatory basis in a larger number of states. Among states indicating that the enrollment approach for a given group or groups varied, the location of LTSS services provided (residential versus community-based) was a frequently cited basis of variation. States with Financial Alignment Demonstrations for dual eligibles in addition to other managed care programs also often cited varying enrollment criteria for dual eligibles.

| Exhibit 4: MCO Enrollment of Populations with Special Needs, July 1, 2018 (# of States) |

||||||||

| Non-Dual/Non-LTSS: | Non-Dual/Receives LTSS: | Dual Eligibles | ||||||

| Pregnant women | Foster children | CSHCNs | Persons with SMI/SED | Persons with I/DD | Persons w/ physical disabilities | Seniors | ||

| Always mandatory | 36 | 22 | 25 | 23 | 10 | 17 | 15 | 11 |

| Always voluntary | 2 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Varies | 0 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 14 |

| Always excluded | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 10 |

| Notes: “CSHCNs” – children with special health care needs, “SMI/SED” – persons with serious mental illness or serious emotional disturbance, “I/DD” – persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. | ||||||||

Acute Care Managed Care Population Changes

In both FY 2018 and FY 2019, only a few states reported actions to increase enrollment in acute care managed care, reflecting full or nearly full MCO saturation in most MCO states. As described above, Alaska and Arkansas reported plans to implement an MCO program for the first time in FY 2019. Of the 39 states with MCOs already in place as of July 1, 2018, five states in FY 2018 and five states in FY 2019 indicated that they made specific policy changes to increase the number of enrollees in MCOs through geographic expansion, voluntary or mandatory enrollment of new groups into MCOs, or mandatory enrollment of specific eligibility groups that were formerly enrolled on a voluntary basis (Exhibit 5). Thirty-seven states reported that acute care MCOs were operating statewide as of July 2018, including Illinois, which expanded MCOs statewide in FY 2018. The remaining two MCO states without statewide programs (Colorado and Nevada) did not report a geographic expansion planned for FY 2019.

| Exhibit 5: Medicaid Acute Care Managed Care Population Expansions, FY 2018 and FY 2019 | ||

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | |

| Geographic Expansions | IL | — |

| New Population Groups Added | PA, TX, VA | IL, NH, OH, PA, VA |

| Voluntary to Mandatory Enrollment | WI | — |

| Implementing an MCO program for the first time | — | AK, AR |

Two notable acute care MCO expansions relate to programs that combine both acute care and LTSS:

- In January 2018, Pennsylvania began to phase-in its Community HealthChoices (CHC) program which provides both physical health and long-term services and supports through newly contracted MCOs. CHC enrollees include individuals in nursing facilities (currently carved out of managed care after 30 days), full benefit dually-eligible individuals, and individuals receiving home and community-based services.

- Virginia implemented its CCC Plus (Commonwealth Coordinated Care) program in FY 2018 making MCO enrollment mandatory for most LTSS populations.

In FY 2018 and FY 2019, states expanded MCO enrollment (either voluntary or mandatory) to other groups including state wards and foster children (Illinois), expansion adults transitioning from the state’s premium assistance program to MCO coverage (New Hampshire), workers with disabilities and persons receiving Specialized Recovery Services (Ohio), the Breast and Cervical Cancer and Adoption Assistance eligibility groups (Texas), and persons with third party liability coverage (Virginia).

Only one state made enrollment mandatory for a specific eligibility group that was formerly enrolled on a voluntary basis: Wisconsin made enrollment mandatory in FY 2018 for SSI adults with disabilities that do not have long-term care needs, are not enrolled in HCBS or MLTSS, are not tribal members, and are not dual eligibles.

Services Covered Under MCO Contracts

Behavioral Health Services Covered Under MCO Contracts

Although MCOs are at risk financially for providing a comprehensive set of acute care services, nearly all states exclude or “carve-out” certain services from their MCO contracts, frequently behavioral health services. States with acute care MCOs were asked to indicate whether specialty outpatient mental health (MH) services, inpatient mental health services, and outpatient and inpatient substance use disorder (SUD) services are always carved-in (i.e., virtually all services are covered by the MCO), always carved-out (to PHP or FFS), or the carve-in status varies by geographic or other factors. More than half of the 39 MCO states reported that specific behavioral health service types were carved into their MCO contracts, with specialty outpatient mental health services somewhat less likely to be carved in (Exhibit 6 and Table 6).

| Exhibit 6: MCO Coverage of Behavioral Health, July 1, 2018 (# of States) | ||||

| Specialty Outpatient MH* | Inpatient MH | Outpatient SUD | Inpatient SUD | |

| Always carved-in | 22 | 24 | 27 | 26 |

| Always carved-out | 10 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Varies | 7 | 8 | 5 | 7 |

| *“Specialty outpatient mental health” services mean services used by adults with Serious Mental Illness (SMI) and/or youth with serious emotional disturbance (SED), commonly provided by specialty providers such as community mental health centers. | ||||

In FY 2018, Mississippi and South Carolina reported actions to carve behavioral health services into their MCO contracts and Washington reported implementing integrated MCO contracts in additional geographic areas.

In FY 2019, 11 states reported actions impacting the coverage of behavioral health services under MCO contracts:

- Six states (Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia) reported actions to carve behavioral health services into their MCO contracts.

- Arizona and Washington reported plans to implement additional integrated MCO contracts.

- Michigan reported a plan to implement pilot programs that would provide both physical and behavioral health services.

- Ohio reported a full carve-in of behavioral health services as of July 1, 2018.

- Arkansas reported plans to implement a new MCO program to serve beneficiaries who have complex behavioral health and intellectual and developmental disabilities needs.

Institutions for Mental Disease (IMD) “In Lieu OF” Rule

The 2016 Medicaid Managed Care Final Rule12 allows states (under the authority for health plans to cover services “in lieu of” those available under the Medicaid state plan), to receive federal matching funds for capitation payments on behalf of adults who receive inpatient psychiatric or substance use disorder (SUD) treatment or crisis residential services in an IMD for no more than 15 days in a month.13 States were asked whether or not they planned to use this new authority. Of the 39 states with MCOs as of July 1, 2018, 28 states answered “yes” for both FYs 2018 and 2019; three states reported plans to begin using this authority in FY 2019; and five states answered “no.”14 Also, North Carolina reported using “in lieu of” authority in its PHP contract and Arkansas reported plans to use this authority when it launches its new MCO program in January 2019. At the time this report was being finalized, however, the SUPPORT Act15 was expected to be signed into law creating a new state option from October 1, 2019 to September 30, 2023 to cover IMD services for up to 30 days in a year for individuals with an SUD. The SUPPORT Act also codified the 2016 Medicaid Managed Care Final Rule provision allowing MCOs to offer “in lieu of” IMD coverage for up to 15 days in a month.

Additional Services

Thirty-seven states with MCO contracts as of July 1, 2018, reported that MCO plans in their states may offer a range of services beyond those described in the state plan or waivers. The most common additional services reported were limited or enhanced adult dental services beyond contractually required state plan benefits, enhanced vision services for adults, and enhanced transportation services. Other value-added services reported included enhanced care coordination, wellness incentives, waiving co-payments, routine or school/sports physicals, and diabetic, weight-loss, tobacco cessation, and chiropractic services. Several states noted that MCOs offer services that address social determinants of health, including GED coaching, housing support, mother and baby supports, educational services and food access services. Others reported offering services/items to promote safety, including helmets and infant car seats.

Managed Care (Acute and LTSS) Quality, Contract Requirements, and Administration

Quality Initiatives

Over time, the expansion of comprehensive risk-based managed care in Medicaid has been accompanied by greater attention to measuring quality and plan performance and, increasingly, to measuring health outcomes. After years of comprehensive risk-based managed care experience within the Medicaid program, many states now incorporate quality into the procurement process, as well as into ongoing program monitoring.16

States procure MCO contracts using different approaches; however, most states use competitive bidding, in part because the dollar value is so large. Under these procurements, states can specify requirements and criteria that go beyond price, and may expect plans to compete on the basis of value-based payment arrangements with network providers, specific policy priorities such as improving birth outcomes, strategies to address social determinants of health, and/or other specific performance and quality criteria. In this year’s survey, states were asked if they used, or planned to use, the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s (NCQA’s) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS®) scores as criteria for selecting MCOs. Of the 39 states with MCOs, 14 indicated that they use or plan to use HEDIS scores as criteria for selecting MCOs.

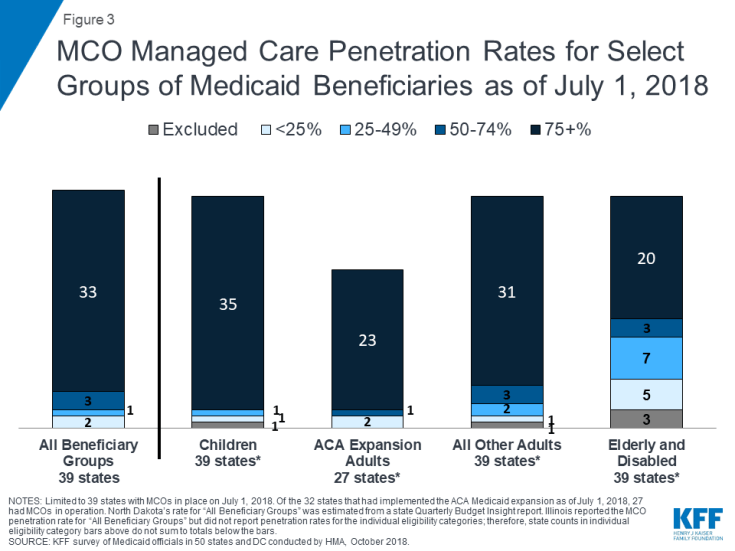

Nearly all MCO states (35 states) reported using at least one select Medicaid managed care quality initiative in FY 2018 (Figure 4 and Table 7). States were asked to indicate whether they had specific managed care quality strategies (acute and/or MLTSS) in place in FY 2018 and to identify newly added or expanded initiatives for FY 2019. More than three quarters of MCO states reported having initiatives in place in FY 2018 that make MCO comparison data publicly available. More than half of MCO states reported capitation withhold arrangements and/or pay for performance incentives in FY 2018. Fewer states reported use of an auto-assignment algorithm that includes quality performance measures.

In FY 2019, 17 MCO states expect to implement new or expanded quality initiatives (Figure 4). The predominance of states reporting new or expanded activity in FY 2019 reported activity related to enhancing/expanding existing initiatives. However, two states reported new initiatives. Utah is planning to create a public facing dashboard for its acute care MCOs to make comparison data publicly available in FY 2019 and Louisiana is planning to add quality as a component to its auto-assignment algorithm for acute care contracts in calendar year 2019 (Table 7).

| State-mandated Performance Improvement Project Examples |

| Federal regulations mandate that states must require, under contracts starting on or after July 1, 2017, each MCO or PHP to establish and implement an ongoing comprehensive quality assessment and performance improvement program for Medicaid services. Performance Improvement Projects (PIPs) may be designated by CMS, by states, or developed by health plans, but must be designed to achieve significant, sustainable improvement in health outcomes and enrollee satisfaction. In this year’s survey, states were asked to indicate whether they mandate MCO PIPs in a particular focus area. States reported a range of state-mandated PIP focus areas, including prenatal smoking and antipsychotic medication use in children (Kentucky), diabetes prevention and management and clinical depression screening and management (New Mexico), child health (Ohio), strengthening care coordination and encouraging transitions from nursing facilities to community care (Pennsylvania), and individuals with complex needs, especially those with comorbid anxiety and depression (Texas). |

Contract Requirements

Alternative [Provider] Payment Models Within MCO Contracts

Value-based purchasing (VBP) strategies are important tools for states pursuing improved quality and outcomes and reduced costs of care within Medicaid and across payers. Generally speaking, VBP strategies include activities that hold a provider or MCO accountable for cost and quality of care.17 This often includes efforts to implement alternative payment models (APMs) which replace FFS/volume-driven provider payments with payment models that incentivize quality, coordination, and value (e.g., shared savings/shared risk arrangements and episode-based payments). Many states included a focus on adopting and promoting APMs as part of their federally-supported State Innovation Model (SIM) projects and as part of delivery system reform efforts approved under Section 1115 Medicaid waivers.18 A growing number of states are encouraging or requiring Medicaid MCOs to adopt APMs to advance VBP in Medicaid.

More than half of MCO states (23 states) identified a specific target in their MCO contracts for the percentage of provider payments, network providers, or plan members that MCOs must cover via alternative provider payment models in FY 2018 (Exhibit 7). (Only 13 states identified having a target percentage in place in FY 2017 and five states in FY 2016.) Four additional states plan to add a target percentage in FY 2019.

| Exhibit 7: States that Require MCOs to Meet a Target % for Provider APMs | ||

| # of States | States | |

| In Place FY 2018 | 23 | AZ, CA, DC, DE, HI, IA, LA, MA, MN, MO, NE, NH, NM, NY, OH, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, WA, WI, WV |

| Plan to Begin in FY 2019 | 4 | FL, OR, UT, VA |

In FY 2018, 10 states had contracts that required Medicaid MCOs to adopt specific alternative provider payment models (e.g., episode of care payments, shared savings/shared risk, etc.), while eight states had contracts that encouraged MCOs to adopt specific APMs (Exhibit 8). In FY 2019, three additional states plan to require the use of specific APMs while four additional states plan to encourage specific APMs. CMS launched a Learning and Action Network (LAN) in 2015 to encourage alignment across public and private sector payers by providing a forum for sharing best practices and developing common approaches to designing and monitoring of APMs, as well as by developing evidence on the impact of APMs.19 Several states reported use of the LAN framework in devising MCO APM requirements (see examples below).

| Exhibit 8: States that Require vs. Encourage the Use of Specific APMs | ||||

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | |||

| Require | 10 States | IA, LA, NE, NM, OH, PA, RI, TN, WA, WV | 3 States | AZ, KS, MI |

| Encourage | 8 States | DC, DE, IL, MA, NH, NY, TX, VA | 4 States | NJ, OR, UT, WI |

| State APM Strategies for Medicaid MCO Contracts |

|

Social Determinants of Health

In April 2017, the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation selected 32 organizations to implement and test models to support local communities in addressing the health-related social needs of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries, aiming to bridge the gap between clinical and community service providers. This “Accountable Health Communities” (AHC) model represents the first CMS innovation model that focuses on social determinants of health. The goal of the five-year program is to encourage innovation to deliver local solutions that improve access to community-based services.21 As part of this effort, CMS has developed an AHC Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool. This increased attention to social determinants of health is also seen at the state level, where many states have looked to Medicaid MCOs to develop strategies to identify and address social determinants of health.

The survey found that 16 states required, while 10 states encouraged MCOs to screen enrollees for social needs and/or provide referrals to social services in FY 2018 (Exhibit 9). In FY 2019, three additional states plan to require, while six additional states plan to encourage MCOs to screen/refer enrollees for social needs in FY 2019.

| Exhibit 9: States that Require vs. Encourage MCOs to Screen for Social Needs and/or Provide Referrals to Social Services | ||||

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | |||

| Require | 16 States | CA, DC, DE, GA, IL, LA, MA, MD, MO, NE, NM, PA, RI, TN, VA, WI | 3 States | FL, HI, WV |

| Encourage | 10 States | AZ, CO, IA, KY, MI, NJ, NV, NY, TX, WA | 6 States | AR,22 IN, MS, NH, OH, OR |

| State Strategies to Address Social Determinants of Health |

|

In response to a new survey question, three states (Iowa, Massachusetts, and New Jersey) reported that they tie MCO incentive payments or withholds to a social determinants-related measure. One state (Colorado) reports that Rocky Mountain Health Plan, which participates in the federal AHC pilot described above, will adopt a social determinant-related measure in FY 2019. In Massachusetts, the state’s approach to accountable care organizations includes shared savings and losses that they expect will also be impacted by an organization’s attention to social determinants. In addition, Massachusetts uses a social determinants of health model to risk adjust MCO capitation rates for Medicaid ACO/MCO contracts, and the state plans to have a continuous risk adjuster for Senior Care Options and One Care that will include social determinants of health in a similar manner.

Criminal Justice-Involved Populations

Engaging Medicaid MCOs in efforts to improve continuity of care for individuals released from correctional facilities into the community is important to ensure that individuals with complex or chronic health conditions, including behavioral health needs, have an effective transition to treatment in the community. In FY 2018, six states required MCOs to provide care coordination services to at least some enrollees prior to release from incarceration, while five states encouraged MCOs to provide care coordination services prior to release. Four states intend to use contracts to require or encourage such care coordination in FY 2019 (Exhibit 10). New Mexico will move from encouraging to requiring plans to participate in care coordination to facilitate the transition of members from prisons, jails, and detention facilities into the community.

| Exhibit 10: States that Require vs. Encourage MCOs to Provide Care Coordination Services to Enrollees Prior to Release from Incarceration | ||||

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | |||

| Require | 6 States | AZ, KS, LA, OH, WA, WI | 2 States | NM, VA |

| Encourage | 5 States | CO, IA, KY, NM, PA | 2 States | DE, MA |

| State Care Coordination Examples for Enrollees Pre-Release from Incarceration |

|

Administrative Policies

Minimum Medical Loss Ratios

The Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) is the proportion of total capitation payments received by an MCO spent on clinical services and quality improvement. CMS published a final rule in 2016 that requires states to develop capitation rates for Medicaid to achieve an MLR of at least 85% in the rate year, for rating periods and contracts starting on or after July 1, 2019. States must include requirements for plans to calculate and report an MLR for contracts that take effect on or after July 1, 2017.23 This 85% minimum MLR is the same standard that applies to Medicare Advantage and private large group plans. There is no federal requirement that Medicaid plans must pay remittances to the state if they fail to meet the MLR standard, but states have discretion to require remittances.

Some states reported that their MLR requirement for acute care contracts and/or MLTSS exceeds the 85% minimum, while other states noted that they do not yet specify an MLR.24 States were asked whether they require MCOs that do not meet the minimum MLR requirement to pay remittances. Twenty states reported that they always require MCOs to pay remittances, while five states indicated they sometimes require MCOs to pay remittances (Exhibit 11).

| Exhibit 11: Medicaid MCO Minimum Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) Remittance Requirements as of July 1, 2018 | ||

| # of states | States | |

| State always requiring remittance | 20 | CO, DE, IA, IL, IN, KY, LA, MD, MN, MO, NE, NV, NJ, NY, OR, PA, SC, VA, WA, WV |

| State sometimes requiring remittance | 5 | CA, KS, MA, MS, OH |

PCCM and PHP Program Changes

Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) Program Changes

Of the 14 states with PCCM programs, two reported enacting policies to increase PCCM enrollment in FY 2018 or FY 2019. Colorado reported growth in its PCCM-based Accountable Care Collaboratives in both FY 2018 and FY 2019. Massachusetts reported that member transitions related to the implementation of its Accountable Care Organization (ACO) program in FY 2018 had the overall effect of increasing PCCM enrollment in FY 2018.

Two other states reported new PCCM programs:

- Alabama reported plans for FY 2019 to replace its current PCCM program (Patient 1st) and Maternity PHP program with a new PCCM entity program (the Alabama Coordinated Health Network) that will cover care coordination services. Alabama is also planning to implement a second PCCM entity program in FY 2019 (the Alabama Integrated Care Network) that will provide enhanced case management, education, and outreach services to most LTSS recipients in both HCBS and institutional settings.

- Arizona implemented an American Indian Medical Home in FY 2018 using PCCM authority and enrollment is expected to expand in FY 2019.

Four states (Idaho, Illinois, Nevada, and Vermont) reported actions to decrease enrollment in a PCCM program in FY 2018 or FY 2019. Idaho is transitioning dual eligibles from PCCM to its Medicaid-Medicare Coordinated Plan in FY 2019; Illinois reported ending its PCCM program when its MCO program was expanded statewide in FY 2018; Nevada ended its Health Care Guidance Program on June 30, 2018; and Vermont is decreasing its PCCM payment over the first half of FY 2019 and will end the payment effective January 1, 2019.

Limited-Benefit Prepaid Health Plans (PHP) Changes

In this year’s survey, the 28 states contracting with at least one PHP as of July 1, 2018, were asked to indicate whether certain services (listed in Exhibit 12 below) were provided under these arrangements. The most frequently cited services provided (of those included in the question) were outpatient mental health services (14 states), followed by outpatient substance use disorder (SUD) treatment services, non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT), and dental services (13 states each).

| Exhibit 12: Services Covered Under PHP Contracts, July 1, 2018 | ||

| # of States | States25 | |

| Outpatient Mental Health | 14 | CA, CO, HI, ID, LA, MA, MI, NC, OR, PA, TN*, UT, WA, WI |

| Inpatient Mental Health | 12 | CA, CO, HI, LA, MA, MI, NC, PA, TN*, UT, WA, WI |

| Outpatient SUD Treatment | 13 | CA, CO, ID, LA, MA, MI, NC, OR, PA, TN*, UT, WA, WI |

| Inpatient SUD Treatment | 10 | CA, CO, MA, MI, NC, PA, TN*, UT, WA, WI |

| Non-Emergency Medical Transportation (NEMT) | 13 | FL, IA, IN, KY, ME, MI, NJ, OK, RI, TN*, TX, UT, WI |

| Dental | 13 | AR, CA, IA, ID, LA, MI, NE, NV, RI, TN*, TX, UT, WI |

| Long-Term Services and Supports | 6 | ID, MI, NC, NY, TN*, WI |

| Vision | 2 | TN*, WI |

| * In addition to separate dental and vision PHPs, TN contracts with a non-risk PHP to provide comprehensive benefits (physical health, behavioral health and LTSS) to children who are in foster care, receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI), or receive care in certain institutional settings. | ||

Twelve states reported implementing policies to increase PHP enrollment in FY 2018 or FY 2019. Seven states (Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, Nebraska, Nevada, Utah, and Washington) reported new or expanded dental PHPs in FY 2018 or planned for FY 2019. Other states reported the following changes: increased enrollment in its Drug Medi-Cal PHPs (California); increased enrollment in its dual eligible PHP (Idaho); implementation of a NEMT PHP (Indiana); enrollee transitions related to the implementation of its ACO initiative which increased behavioral health PHP enrollment (Massachusetts); and increased enrollment in its LTSS PHPs (New York).

Four states also reported actions that decreased PHP enrollment in FY 2018 or FY 2019. Alabama reported plans to end its maternity care PHP (when its new PCCM-entity program is implemented); Kentucky reported that it is planning to eliminate coverage under its NEMT PHP for expansion adults; Washington reported that enrollment in its behavioral health PHPs is decreasing as the state converts behavioral health PHPs to fully integrated MCO contracts in additional geographic areas; and Wyoming reported ending its PHP arrangement for children with emotional disturbance.

In this year’s survey, states with PHPs were also asked to briefly describe PHP contract quality strategies in place in FY 2018 or planned for FY 2019. Nearly two-thirds of states with PHPs reported a variety of quality strategies including tracking of HEDIS and/or other measures; requiring Performance Improvement Projects; incentive payments; withholds tied to performance measures; public reporting of performance results (e.g., report cards or dashboards); imposition of penalties or liquidated damages; and use of alternative payment methods.

Table 4: Share of the Medicaid Population Covered Under Different Delivery Systems in all 50 States and DC, as of July 1, 2018

| States | Type(s) of Managed Care In Place | Share of Medicaid Population in Different Managed Care Systems | ||

| MCO | PCCM | FFS / Other | ||

| Alabama | PCCM | — | 93.5% | 6.5% |

| Alaska | FFS | — | — | 100.0% |

| Arizona | MCO | 93.0% | — | 7.0% |

| Arkansas* | PCCM | — | NR | NR |

| California | MCO and PCCM* | 83.0% | — | 17.0% |

| Colorado | MCO and PCCM* | 10.1% | 89.9% | 0.0% |

| Connecticut | FFS* | — | — | 100.0% |

| Delaware | MCO | 97.0% | — | 3.0% |

| DC | MCO | 77.0% | — | 23.0% |

| Florida | MCO | 92.0% | — | 8.0% |

| Georgia | MCO | 83.0% | — | 17.0% |

| Hawaii | MCO | 99.9% | — | 0.1% |

| Idaho* | PCCM | — | 92.0% | 8.0% |

| Illinois | MCO | 80.0% | — | 20.0% |

| Indiana | MCO | 84.0% | — | 16.0% |

| Iowa | MCO | 92.6% | — | 7.4% |

| Kansas | MCO | 95.0% | — | 5.0% |

| Kentucky | MCO | 91.0% | — | 9.0% |

| Louisiana | MCO | 91.2% | — | 8.8% |

| Maine | PCCM | — | 50.0% | 50.0% |

| Maryland | MCO | 86.0% | — | 14.0% |

| Massachusetts | MCO and PCCM | 43.0% | 25.0% | 32.0% |

| Michigan | MCO | 77.6% | — | 22.4% |

| Minnesota | MCO | 84.0% | — | 16.0% |

| Mississippi | MCO | 65.0% | — | 35.0% |

| Missouri | MCO | 76.0% | — | 24.0% |

| Montana | PCCM | — | 73.0% | 27.0% |

| Nebraska | MCO | 99.7% | — | 0.4% |

| Nevada | MCO | 79.0% | — | 21.0% |

| New Hampshire* | MCO | 73.8% | — | 3.9% |

| New Jersey | MCO | 95.0% | — | 5.0% |

| New Mexico | MCO | 90.1% | — | 9.9% |

| New York | MCO | 77.2% | — | 22.8% |

| North Carolina | PCCM | — | 90.0% | 10.0% |

| North Dakota | MCO* and PCCM | 22.0% | NR | NR |

| Ohio | MCO | 89.5% | — | 10.5% |

| Oklahoma | PCCM | — | 74.9% | 25.1% |

| Oregon | MCO* | 93.0% | — | 7.0% |

| Pennsylvania | MCO | 84.6% | — | 15.4% |

| Rhode Island | MCO | 91.0% | — | 9.0% |

| South Carolina | MCO* | 77.0% | — | 23.0% |

| South Dakota | PCCM | — | 80.0% | 20.0% |

| Tennessee | MCO | 100.0% | — | 0.0% |

| Texas | MCO | 94.0% | — | 6.0% |

| Utah | MCO | 80.2% | — | 19.9% |

| Vermont | PCCM | — | 63.0% | 37.0% |

| Virginia | MCO | 95.0% | — | 5.0% |

| Washington | MCO and PCCM | 92.0% | 2.0% | 6.0% |

| West Virginia | MCO | 80.0% | — | 20.0% |

| Wisconsin | MCO | 67.0% | — | 33.0% |

| Wyoming | FFS | — | — | 100.0% |

| ‘NOTES: NR – not reported. MCO refers to risk-based managed care; PCCM refers to Primary Care Case Management. FFS/Other refers to Medicaid beneficiaries who are not in MCOs or PCCM programs. *AR – Most expansion adults served by Qualified Health Plans through “Arkansas Works” premium assistance waiver. *CA – PCCM program operates in LA county for those with HIV. *CO – PCCM enrollees are part of the state’s Accountable Care Collaboratives (ACCs). *CT – Terminated its MCO contracts in 2012 and now operates its program on a fee-for-service basis using three ASO entities. *ID – The Medicaid-Medicare Coordinated Plan (MMCP) has been recategorized by CMS as an MCO but is not counted here as such since it is secondary to Medicare. *ND’s total MCO penetration rate estimated from ND DHS Quarterly Budget Insight data for quarter ending 6/30/2018. *NH – 22.3% of overall population and 77% of expansion adults are served by Qualified Health Plans under NH’s premium assistance program waiver *OR – MCO enrollees include those enrolled in the state’s Coordinated Care Organizations. *SC – Uses PCCM authority to provide care management services to approximately 200 medically complex children.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2018. |

||||

Table 5: Enrollment of Special Populations Under Medicaid Managed Care Contracts for Acute Care in all 50 States and DC, as of July 1, 2018

| States | Non-Dual, Non-LTSS Populations | Non-Dual LTSS populations | Duals | |||||

| Pregnant Women | Foster Children | CSHCNs | Persons with SMI/SED | Persons with ID/DD | Persons w/ physical disabilities | Seniors | ||

| Alabama | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| Alaska | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Arizona | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory |

| Arkansas | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| California | Mandatory | Varies | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies |

| Colorado | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary |

| Connecticut | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Delaware | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies |

| DC | Mandatory | Varies | Voluntary | Varies | Excluded | Varies | Excluded | Varies |

| Florida | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Voluntary | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory |

| Georgia | Mandatory | Mandatory | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded |

| Hawaii | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory |

| Idaho | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Illinois | Mandatory | Excluded | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies |

| Indiana | Mandatory | Voluntary | Mandatory | Mandatory | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded |

| Iowa | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory |

| Kansas | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory |

| Kentucky | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Varies |

| Louisiana | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies | Excluded |

| Maine | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Maryland | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies | Excluded | Excluded |

| Massachusetts | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary |

| Michigan | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Varies | Varies | Voluntary |

| Minnesota | Mandatory | Voluntary | Voluntary | Varies | Voluntary | Voluntary | Mandatory | Varies |

| Mississippi | Mandatory | Voluntary | Voluntary | Varies | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded |

| Missouri | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Varies | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded |

| Montana | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Nebraska | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory |

| Nevada | Mandatory | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded |

| New Hampshire | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory |

| New Jersey* | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Mandatory | Voluntary | Mandatory |

| New Mexico | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory |

| New York | Mandatory | Varies | Mandatory | Mandatory | Excluded | Mandatory | Mandatory | Excluded |

| North Carolina | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| North Dakota | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded |

| Ohio | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies |

| Oklahoma | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Oregon | Mandatory | Varies | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Mandatory | Mandatory | Voluntary |

| Pennsylvania | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies |

| Rhode Island | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Voluntary | Voluntary | Voluntary | Varies |

| South Carolina | Mandatory | Voluntary | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies | Excluded | Varies |

| South Dakota | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Tennessee | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory |

| Texas | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies |

| Utah | Mandatory | Varies | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies |

| Vermont | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Virginia | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory | Mandatory |

| Washington | Mandatory | Voluntary | Mandatory | Mandatory | Varies | Mandatory | Varies | Varies |

| West Virginia | Mandatory | Excluded | Varies | Varies | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded | Excluded |

| Wisconsin | Mandatory | Varies | Varies | Varies | Voluntary | Mandatory | Varies | Varies |

| Wyoming | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Mandatory | 36 | 22 | 25 | 23 | 10 | 17 | 15 | 11 |

| Voluntary | 2 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Varies | 0 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 14 |

| Excluded | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 10 |

| ‘NOTES: “–” indicates there were no MCOs operating in that state’s Medicaid program as of July 1, 2018. I/DD – intellectual and developmental disabilities, CSHCN – Children with special health care needs, SMI – Serious Mental Illness, SED – Serious Emotional Disturbance. States were asked to indicate for each group if enrollment in MCOs is “Mandatory,” “Voluntary,” “Varies,” or if the group is “Excluded” from MCOs as of July 1, 2018. *NJ: Nursing facility residents as of July 1, 2014 were grandfathered and remain excluded from MCO enrollment unless they experience a change in eligibility status or are discharged from the nursing facility.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2018. |

||||||||

| States | Specialty OP Mental Health | Inpatient Mental Health | Outpatient SUD | Inpatient SUD |

| Alabama | — | — | — | — |

| Alaska | — | — | — | — |

| Arizona | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies |

| Arkansas | — | — | — | — |

| California | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out |

| Colorado | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out |

| Connecticut | — | — | — | — |

| DC | Varies | Varies | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Delaware | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-in |

| Florida | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Georgia | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Hawaii | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Idaho | — | — | — | — |

| Illinois | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Indiana | Varies | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Iowa | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Kansas | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Kentucky | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Louisiana | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Maine | — | — | — | — |

| Maryland | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out |

| Massachusetts | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Michigan | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out |

| Minnesota | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Mississippi | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Varies | Varies |

| Missouri | Always Carved-out | Varies | Varies | Varies |

| Montana | — | — | — | — |

| Nebraska | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Nevada | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| New Hampshire | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| New Jersey | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies |

| New Mexico | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| New York | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| North Carolina | — | — | — | — |

| North Dakota | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Ohio | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Oklahoma | — | — | — | — |

| Oregon | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Pennsylvania | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out |

| Rhode Island | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| South Carolina | Always Carved-in | Varies | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| South Dakota | — | — | — | — |

| Tennessee | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Texas | Varies | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Utah | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out | Always Carved-out |

| Vermont | — | — | — | — |

| Virginia | Always Carved-out | Varies | Always Carved-in | Varies |

| Washington | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies |

| West Virginia | Always Carved-in | Varies | Always Carved-in | Varies |

| Wisconsin | Varies | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in | Always Carved-in |

| Wyoming | — | — | — | — |

| Always Carved-in | 22 | 24 | 27 | 26 |

| Always Carved-out | 10 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Varies | 7 | 8 | 5 | 7 |

| NOTES: OP – Outpatient. SUD – Substance Use Disorder. “–” indicates there were no MCOs operating in that state’s Medicaid program in July 2018. For beneficiaries enrolled in an MCO for acute care benefits, states were asked to indicate whether these benefits are always carved-in (meaning virtually all services are covered by the MCO), always carved-out (to PHP or FFS), or whether the carve-in varies (by geography or other factor). “Specialty outpatient mental health” refers to services utilized by adults with Serious Mental Illness (SMI) and/or youth with serious emotional disturbance (SED) commonly provided by specialty providers such as community mental health centers.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2018. |

||||

| States | Pay for Performance/ Performance Bonus |

Capitation Withhold | Auto-Assignment Algorithm Includes Quality Performance Measures | Publicly Available Comparison Data About MCOs | Any Select Quality Initiatives | |||||

| In Place FY 2018 |

New or Expanded FY 2019 |

In Place FY 2018 |

New or Expanded FY 2019 |

In Place FY 2018 |

New or Expanded FY 2019 |

In Place FY 2018 |

New or Expanded FY 2019 |

In Place FY 2018 |

New or Expanded FY 2019 |

|

| Alabama | ||||||||||

| Alaska | ||||||||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | |||||||

| Arkansas | ||||||||||

| California | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Colorado | X | X | X | |||||||

| Connecticut | ||||||||||

| DC | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Florida | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Georgia | X | X | ||||||||

| Hawaii | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Idaho | ||||||||||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Indiana | X | X | X | |||||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Kansas | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Kentucky | X | X | ||||||||

| Louisiana | X | X* | X | X | X | |||||

| Maine | ||||||||||

| Maryland | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | |||||||

| Mississippi | ||||||||||

| Missouri | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Montana | ||||||||||

| Nebraska | X | X | X | |||||||

| Nevada | X | X | X* | X | X | X | ||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | ||||||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | |||||||

| New York | X | X | X | |||||||

| North Carolina | ||||||||||

| North Dakota | ||||||||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Oklahoma | ||||||||||

| Oregon | X | X | X | |||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| South Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| South Dakota | ||||||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Utah | X* | X | ||||||||

| Vermont | ||||||||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Washington | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| West Virginia | ||||||||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Wyoming | ||||||||||

| Totals | 25 | 6 | 26 | 6 | 9 | 2 | 31 | 6 | 35 | 17 |

| NOTES: States with MCO contracts were asked to report if select quality initiatives were included in contracts in FY 2018, or are new or expanded in FY 2019. The table above does not reflect all quality initiatives states have included as part of MCO contracts. “*” indicates that a policy was newly adopted in FY 2019, meaning that the state did not have any policy in that category/column in place in FY 2018.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2018. |

||||||||||