Opioid overdose deaths, primarily driven by fentanyl, have surged during the pandemic, exposing significant gaps in access to and availability of treatment. From 2016 to 2021, opioid overdose deaths nearly doubled, from 42,249 to 80,411. By 2021, these deaths accounted for 75% of all fatal drug overdoses, up from 66% in 2016. Rises in overdose deaths have been particularly sharp among people of color and young people. Policy efforts have focused on enhancing access to medications for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) treatment, which can substantially reduce overdose and mortality rates. Yet, approximately 75% of people with OUD do not receive the recommended treatment, and treatment rates are generally lower among people of color and adolescents.

Currently, three medications are approved for OUD treatment: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Buprenorphine and methadone, both controlled substances, have unique administration requirements. Buprenorphine can be prescribed and picked up from a pharmacy, while methadone must be dispensed through licensed opioid treatment programs.

Federal policies governing substance use disorder treatment have undergone rapid changes during the pandemic; however, the extent to which these changes can address the surge in opioid overdose deaths is unclear. Some of these policy adjustments are permanent, while others could revert to pre-pandemic regulations. In this brief, we examine the following 5 key federal policies and implications for access and treatment for OUD:

- Access to buprenorphine medication via telehealth

- Changes to dispensing methadone

- Changes to provider regulations for the prescribing of buprenorphine

- Changes in access to opioid overdose prevention and reversal methods

- Guidance to leverage Medicaid for pre- and post-release from prison access to OUD treatment services

1. Access to Buprenorphine Medication via Telehealth

In response to the pandemic, it became possible to initiate buprenorphine treatment via telehealth without the necessity of an in-person visit, resulting in a shift in access. This modification was largely due to the temporary relaxation of provisions within the Ryan Haight Act of 2008. Ordinarily, this act mandates an in-person visit prior to the prescription of controlled substances, although exceptions are permitted during a Public Health Emergency (PHE). Given the PHE declaration, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was able to suspend in-person visit requirements, thereby improving treatment accessibility to prescriptions for controlled substances like buprenorphine over telehealth.

The DEA temporarily extended pandemic-era telehealth flexibility in response to public feedback and concerns over OUD treatment access. Initially, the DEA proposed two rules which would reinstate many aspects of the pre-pandemic telehealth regulations, including generally requiring an initial in-person visit for some controlled substance prescriptions, with some exceptions. One of the proposals included a modification for buprenorphine, requiring an in-person consultation with a provider within 30 days of prescription. However, the proposed rules were met with resistance, including concerns about potential disruptions in treatment access. In response, the DEA and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) opted to temporarily continue the flexible telehealth policies established during the pandemic, an interim decision that allows the DEA time to balance the potential effects of the proposed regulations on healthcare accessibility against its concerns about diversion.

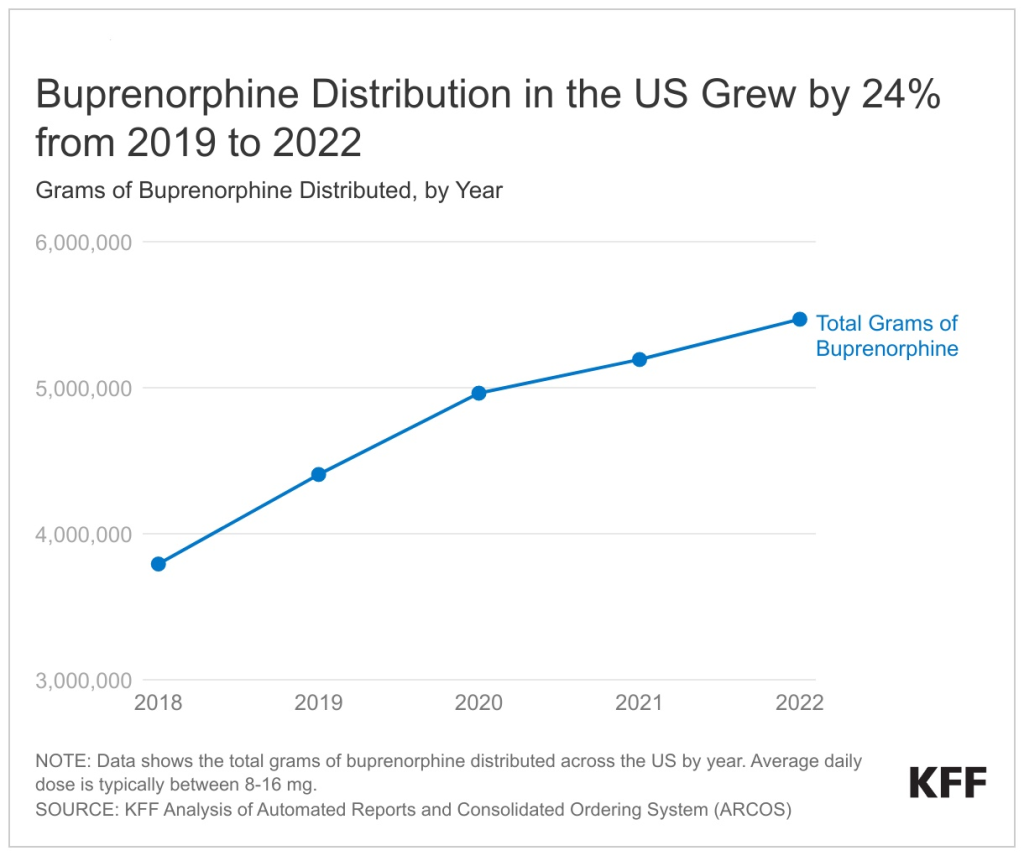

In 2022, buprenorphine dispensing grew by 24% compared to pre-pandemic levels in 2019 but it is unclear whether steps to improve access to buprenorphine are reaching people of color (Figure 1). This upward trend, already in motion before the pandemic due to various policies and/or increases in underlying treatment demand, continued through the pandemic, despite other pandemic-related barriers that resulted in declining health care utilization. Preliminary studies show that telehealth boosted access and retention in care without raising the risk of buprenorphine-related overdoses. Despite these access improvements, it is unclear whether buprenorphine access has improved among communities of color. Prior to the pandemic, research found that compared to White people, Black and Hispanic people have limited access to buprenorphine. The uptake of medication-assisted treatment services has also remained low among American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) people. AIAN and Black communities experienced the highest rates of opioid overdose deaths in 2021 (38.7 and 33.5 per 100,000, respectively) compared to all other racial and ethnic groups. Separately, although telehealth may improve treatment accessibility, barriers remain for many individuals, including limited access to broadband, digital literacy issues, and affordability.

2. Changes to Dispensing Methadone

Methadone dispensing for opioid use disorder treatment is tightly regulated and can only occur through federally and state regulated facilities known as Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs). However, only 5% of zip code tabulation areas have an OTP, potentially limiting their reach. Further, traditionally, methadone was dispensed on-site at OTPs, requiring patients to make daily clinic visits that posed challenges for their work and childcare responsibilities. Consequently, individuals who live far from an OTP or faced other obstacles may be unable to access this treatment option, despite the potential benefits of methadone treatment.

During the pandemic, a temporary policy allowed OTPs to provide some patients with up to 28 days of take-home doses of methadone, a change that may become permanent under a proposed rule. Research suggests this shift eased the burden for patients and may have increased access to treatment for those living farther from OTPs. Though there were increases in methadone-related overdoses during the pandemic, they coincided with overall increases in overdoses, making it unclear whether pandemic-era policy changes contributed to this trend. A recent study found that methadone-related overdose deaths have decreased among Black and Hispanic men since 2020, suggesting that the policy shift has benefited certain populations. SAMHSA has proposed a rule to make these extended take-home flexibilities permanent. While SAMHSA considers feedback and evaluates the pros and cons, the COVID-era policies will remain in effect until a year after the public health emergency concludes or the final rule is published.

A DEA rule finalized in 2021 authorizes OTPs to add mobile components to expand their reach—but so far uptake has been limited. These mobile units operate as extensions of accredited OTPs and are designed to provide methadone treatments to areas where it’s needed most. Despite the potential benefits, the adoption of this initiative has been somewhat limited with 27 mobile treatment programs registered across 13 states. These mobile treatment components aim to mitigate transportation or other logistical challenges by bringing the treatment directly to those in need. They can travel to rural regions or areas experiencing high rates of overdoses to administer methadone, buprenorphine, or other treatments for opioid use disorders. DEA regulations require these mobile units to return to their associated OTP at the end of each day. Although these mobile components are not required to undergo a separate DEA registration process, they must secure approval from the DEA before commencing operations. OTP decisions about whether to expand through mobile components may also be influenced by implementation costs or state regulations. For example, some states place strict requirements on dosing or require that all patients have a government ID to access OTP treatment.

3. Changes to Provider Regulations for the Prescribing of Buprenorphine

Recent legislation vastly increases the potential OUD workforce by allowing providers with a DEA registration to prescribe buprenorphine, a key medication used to treat OUD. Previously, providers had to navigate numerous administrative steps and training to obtain an X-waiver, which granted them authorization to prescribe buprenorphine to treat OUD. However, through a series of legislative efforts, these requirements have gradually been reduced over time. Most recently, legislation passed as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) completely eliminated the X-waiver requirement in response to calls for policy change and the ongoing opioid epidemic. As a result, all prescribers with a current DEA registration that includes Schedule III authority can now prescribe buprenorphine for an OUD treatment, in accordance with state laws.

While the removal of the X-waiver increases the number of providers allowed to prescribe buprenorphine without additional administrative steps, it is unclear how many will use the new authority and whether populations with high needs – including communities of color – will be reached. Along with increasing the number of providers authorized to prescribe buprenorphine (figure 3), the removal of the X-waiver also eliminates limits on the number of patients providers were able to treat. However, even among providers who obtained an X-waiver, a substantial share may only prescribe to a handful of patients, if any. There are many reasons behind this, including skepticism about using medication for opioid use disorder treatment, lack of time, insufficient reimbursement rates, perceived scarcity of professional or mental health support, and apprehension over medication diversion or amplified DEA monitoring. While buprenorphine treatment capacity has grown over time, research suggests that even as restrictions for buprenorphine prescribing were relaxed during the pandemic, growth in obtaining X-waivers slowed, particularly among physicians. In recent years, advanced practice nurses have largely contributed to growth in buprenorphine treatment capacity; however, in many states they are restricted by required physician oversight. It may not be possible to increase the number of providers who can prescribe buprenorphine without addressing these issues and other systemic issues, such as inconsistent access to buprenorphine in pharmacies. Research also suggests that increasing OUD treatment prescribers has not addressed longstanding issues of inequitable buprenorphine distribution across racial and ethnic groups. The lack of a diverse mental health care workforce and culturally informed care may further contribute to treatment barriers among communities of color.

A one-time eight-hour training on SUD treatment and management is required for most DEA-registered providers, which may increase provider knowledge or willingness to treat OUD. Prior research has shown that most providers have received limited training in SUD treatment, which may contribute to hesitation in treating OUD. A study examining state policies related to buprenorphine prescribing found that states with additional training requirements for providers have higher rates of buprenorphine prescribing, suggesting that provider training and education may be linked to increased access to buprenorphine treatment. The CAA included legislation mandating this SUD training for all DEA-registered providers, exempting some with qualifying prior SUD training. This increase in providers who will have SUD training is parallel to the number of prescribers who are newly eligible to prescribe buprenorphine following the elimination of the X-waiver requirement.

4. Changes in Access to Opioid Overdose Prevention and Reversal Methods

Illicit fentanyl, known for its higher potency and increased risk of overdose, has become pervasive in various drug supplies. The primary driver of fatalities is illegally produced fentanyl, which can be lethal to both those who intend to use it and those who consume fentanyl-contaminated products unknowingly. This trend extends to those seeking illicitly manufactured pain pills or drugs like cocaine, putting them at risk of fentanyl-induced overdoses. Consequently, the demand for harm reduction measures such as fentanyl test strips and naloxone has risen. Fentanyl test strips allow people who use drugs to identify trace amounts of fentanyl and naloxone can reverse an opioid overdose. However, these resources can be expensive and challenging to obtain.

The FDA’s recent approval of over-the-counter naloxone–a nasal spray to reverse opioid overdose–allows purchase of this life-saving drug without a prescription. Naloxone is recommended for individuals with opioid use disorder or at increased risk of overdose, including people prescribed high doses of opioids for pain, and their friends/family. Soon, over-the-counter naloxone will be available. However, its roughly $50 price may be unaffordable for many, particularly if insurers do not cover these costs or if the process to receive reimbursement is too complex. Even when naloxone is covered by insurance, out of pocket costs can be a financial barrier that prevents access. Further, some research suggests that compared to White people, Black people have limited access to naloxone.

Federal funds under certain grant programs can now pay for fentanyl test strips, which can help determine if drugs have been mixed with fentanyl and provide users with crucial risk information. However, the accessibility of these test strips remains limited. They can sometimes be obtained from social service organizations and health departments. Yet, challenges around ease of access likely remain, especially if the limited organizations distributing fentanyl test strips enforce quantity limits. Additionally, the legality of fentanyl test strips varies across states. As of April 2022, possession of these test strips is illegal in 25 states due to laws considering them drug paraphernalia. However, some states are working to change these laws.

5. Guidance to Leverage Medicaid for Pre- and Post-Release from Prison Access to OUD Treatment Services

After being released from prison, the risk of overdose and death is notably higher, with opioid overdose being a primary cause of mortality. According to a study conducted in Oregon, the risk of opioid overdose after release is 10 times higher compared to the general public. Further, it is estimated that 65% of inmates have a SUD, which is considerably higher than the general prevalence of 18%. In states that expanded Medicaid, most individuals recently released from prison meet income and eligibility requirements for Medicaid coverage. However, there may be delays in enrollment or difficulty connecting to health services. This can lead to gaps in medication or health care, increased ED utilization, and a worsening of existing health conditions. Federal Medicaid law prohibits federal dollars from paying for health care services of inmates in most cases due to a policy known as the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy.

Recent demonstration opportunities under section 1115 allow Medicaid programs to cover pre-release services–including SUD treatment–and transitional supports. States that submit a waiver request for this opportunity must cover medication-assisted treatment, but it is not required to include all three FDA-approved medications for treating OUD —buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone. In January 2023, CMS approved California’s Section 1115 request to cover a package of reentry services for certain groups of incarcerated individuals 90 days prior to release, marking the first approval of a partial waiver of the Medicaid inmate exclusion policy.

As of June 2023, 14 states have submitted section 1115 waivers seeking exemption from the inmate exclusion policy (Figure 4). These pending waivers differ in eligibility requirements, duration of pre-release services, and comprehensiveness of benefits. Given that states submitted these waivers prior to the guidance it is expected that there may be changes prior to approval to come into compliance with the requirements outlined in the guidance.

Looking Ahead

As federal policies evolve, so does the opioid crisis. Illegally produced fentanyl is now responsible for most overdose deaths, and emerging threats like Xylazine—an veterinary tranquilizer—mixed with fentanyl, further complicates the response to the epidemic and escalates the risk of fatal overdoses. Preliminary data from 2022 finds that opioid overdose deaths remain elevated in the U.S., signaling that there are still significant gaps in access to care. While some recent federal policy changes are permanent, others are subject to change as federal rules are finalized. Though new and proposed federal policies have the potential to increase access to care, ongoing challenges, such as behavioral health workforce shortages, low prescribing of buprenorphine by providers, and treatment gaps by race/ethnicity, could limit the effectiveness of new federal strategies.

The impact of federal efforts may be hampered by resource limitations or state laws. For instance, while OTPs could expand their reach through mobile units, the upfront resource demands might be too burdensome for some programs. Similarly, despite federal funding allowed for fentanyl test strips for some grantees – a potential overdose reduction measure – their accessibility remains limited or illegal in many states due to their classification as drug paraphernalia.

Federal lawmakers are considering the extension or introduction of new strategies to combat the opioid epidemic. Discussions are ongoing regarding whether to extend or permanently classify fentanyl analogs as top-tier controlled substances, affecting penalties for illegal possession and distribution. Congress is engaged in discussions to reauthorize the 2018 SUPPORT Act, addressing the opioid crisis, including funding extensions and proposals for new provisions. Further, federal directives for a public education campaign seek to heighten and spread awareness of the more potent illicit fentanyl which has spread in various drug supplies across the U.S.

States are simultaneously addressing the opioid epidemic through innovative strategies and are debating the best use of recent opioid settlement funds. State Medicaid programs – which have improved access to behavioral health services in recent years through increasing coverage of SUD services, SUD-focused section 1115 waivers, telehealth expansions, and efforts to expand workforce – are now interpreting new federal guidance on justice re-entry focused 1115 waivers. These waivers can allow states to facilitate the provision of OUD services prior to release from incarceration. Yet, the recent resumption of Medicaid renewals following a three-year pandemic halt—termed ‘Medicaid unwinding’— has already led to many individuals losing coverage, primarily due to procedural rather than eligibility reasons. Coverage loss could disrupt OUD treatment, heightening overdose risks, especially during the fentanyl crisis. As awareness and focus on the changing opioid epidemic increases, our understanding of the most effective policies and remaining gaps in access to care and overdose prevention will continue to evolve.

This work was supported in part by Well Being Trust. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.