Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities: Potential Implications of the Election

Former President Trump and Vice President Harris have taken widely different stances and approaches on recognizing and addressing racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Former President Trump took executive action to prohibit federal agencies and contractors from providing training based on “divisive concepts” such as racism and sexism. As candidate, he has vowed to focus on “anti-White” racism, not racism against people of color. The Biden-Harris Administration has identified advancing racial equity as a federal priority, acknowledged that structural and systemic racism drive disparities, and recognized that social and economic factors play an important role in determining individuals’ health and well-being. Beyond these differences, variation in the candidates’ actions and proposals across different areas of health care, including health coverage, reproductive and maternal health, and immigrant health and well-being are likely to have important implications for future efforts to address health disparities as outlined below.

Health Coverage

Trump’s record as president included plans to repeal or weaken the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and cap and reduce federal Medicaid financing, while Vice President Harris has focused on efforts to “protect and strengthen Medicaid and the ACA.” Trump has said in the recent campaign that he’s not planning to repeal the ACA, though he has said he has “concepts” of a plan to replace it and would create a plan with “much better health care.” Although the Trump Administration never issued a detailed plan to replace the ACA, Trump’s budget proposals as president included plans to convert the ACA into a block grant to states, cap federal funding for Medicaid, and allow states to relax the ACA’s rules protecting people with preexisting conditions. Those plans, if enacted, would have reduced federal funding for health care by about $1 trillion over a decade, with trade-offs of higher out-of-pocket premiums for people, more uninsured, higher spending and greater risk for states, and restrictions in Medicaid eligibility. Under the Biden-Harris Administration, legislation was enacted that provided incentives for remaining non-expansion states to implement the ACA Medicaid expansion and provided enhanced subsidies for people to purchase Marketplace coverage. Harris has proposed making these enhanced subsidies permanent as they are currently set to expire at the end of 2025. Under the Biden-Harris Administration, there has been record ACA enrollment.

Future directions of ACA Marketplace and Medicaid coverage have important implications for racial and ethnic disparities in health coverage. Following the ACA health coverage expansions in 2014, there were large gains in coverage across racial and ethnic groups, which helped to narrow but not eliminate racial disparities in coverage (Figure 1). Continued efforts to increase access to coverage and improve continuity of coverage could further narrow these disparities. Conversely, coverage losses through the Marketplaces or Medicaid could reverse progress and widen disparities. Health coverage plays a key role in enabling people to access health care and protecting families from high medical costs.

Changes to Medicaid may have particularly important implications for racial and ethnic health disparities given that it is a major source of health coverage for people of color. Medicaid helps to fill gaps in private coverage for many people of color, particularly children (Figure 2). Research suggests that ACA Medicaid expansion has contributed to a reduction in racial and ethnic disparities in health coverage. Adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion in the remaining ten non-expansion states could continue to close coverage disparities. Nationally, over six in ten people in the coverage gap are people of color. Moreover, uninsured nonelderly Black people are more likely than White people to fall in the Medicaid “coverage gap” because a greater share live in states that have not implemented the Medicaid expansion.

Reproductive and Maternal Health

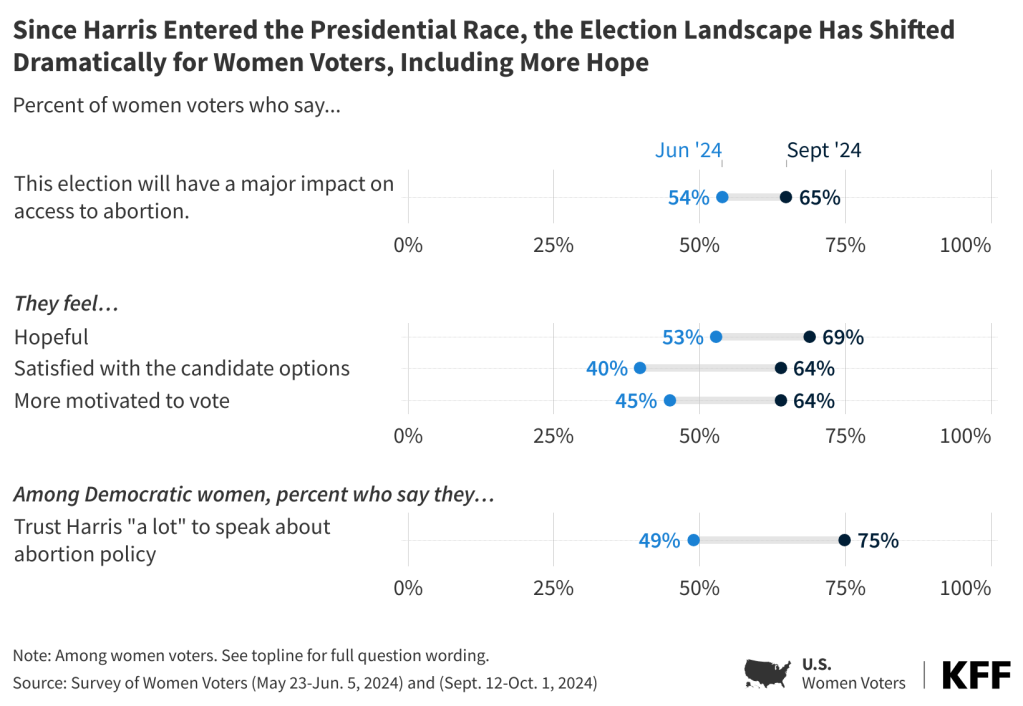

Vice President Harris has been and is an outspoken leader and advocate for reproductive freedom, while former President Trump has taken credit for the overturning of Roe v. Wade and has expressed support for letting states set their own abortion policy, including banning abortion. While abortion is the most prominent health care campaign issue, the election could also have large implications for contraceptive care and maternal health. Vice President Harris’ call for reproductive freedom includes access to contraception. The Trump Administration issued multiple regulations that restricted the availability of funding for contraception. During his campaign, he initially expressed that states could restrict access to contraceptives, but shortly afterwards, also said that he would not support this. As Senator, Vice President Harris sponsored the MOMNIBUS, a package of bills aimed at improving quality of and access to maternity care. Among other actions, under the Biden-Harris Administration, legislation was passed that allows states to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage from 60 days to 12 months. It also released a Maternal Health Blueprint that outlines future priorities. Former President Trump also issued a maternal health plan near the end of his term and signed federal legislation that provided funding for maternal mortality review committees.

The outcome of the election may have important implications for abortion restrictions, which in turn, will likely impact racial and ethnic disparities in maternal health. Pregnancy-related mortality rates among American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) and Black women are over three times higher compared to White women. State restrictions on abortion in the wake of the overturning of Roe v. Wade may widen maternal health disparities. Six in ten Black and AIAN women of reproductive age live in states with bans or restrictions compared to just over half of their White counterparts (Figure 3). People of color also are more likely than their White counterparts to face structural barriers that make it difficult to travel out of state for an abortion.

Future directions of Medicaid coverage for pregnant women and family planning services as well as efforts to improve maternal health also may impact disparities. Medicaid covers about 4 in 10 births nationally, including more than two-thirds among Black and AIAN people. Nearly all states have implemented the option to extend postpartum coverage from 60 days to 12 months, facilitating more continuous coverage during this period. KFF research also has found that the ACA’s Medicaid expansion promotes continuity of coverage in both the prenatal and postpartum periods. Additionally, over half of the states have established programs that use Medicaid funds to cover the costs of family planning services for low-income women who remain uninsured, and Medicaid accounts for 75% of all publicly funded family planning. Moreover, many state Medicaid programs have implemented policies, programs, and initiatives to improve maternity care and outcomes, including expanding coverage for benefits such as doula care, home visits, and substance use disorder and mental health treatment; and using new payment, delivery, and performance measurement approaches.

Immigrant Health and Well-Being

As president and candidate, Trump pursued restrictive immigration policies and spread anti-immigrant rhetoric and misinformation; the Harris campaign has emphasized her tough on crime stance as a former attorney general of a border state and her support for stricter border security. During his presidential term, Trump implemented more restrictive enforcement policies, issued a proclamation suspending entry of immigrants into the United States unless they provided proof of health insurance, rescinded the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, and made changes to public charge policies that newly considered the use of non-cash assistance programs, including Medicaid, to determine whether people could enter the U.S. On the campaign trail, he has promised to carry out the “largest domestic deportation” in American history and to end birthright citizenship for children of undocumented immigrants. He also has spread misinformation about immigrants, describing them as a source of crime, a burden for taxpayers, and a drain on government programs like Medicare and Social Security. The Biden-Harris Administration reversed the Trump Administration’s public charge changes and the proclamation that suspended entry of immigrants unless they provided proof of health insurance. It also extended Marketplace eligibility to DACA recipients in 2024.

The future of immigration policies has important implications for the health and well-being of immigrants. Immigrants face large disparities in health and health care, including high uninsured rates, which reflect immigrant eligibility restrictions on health coverage programs funded by the federal government (Figure 4). Undocumented immigrants are prohibited from accessing federally funded programs, including Medicaid, Medicare, and the ACA Marketplaces, while many lawfully present immigrants are not eligible for these programs when they first arrive to the U.S. They also face barriers to care, including language access challenges, confusion about eligibility for health coverage and other public programs, and immigration-related fears. Earlier KFF analysis found that the policies and actions taken under the Trump Administration increased these fears, making immigrants more reluctant to access health coverage and care. Overall, research shows that immigrants use less health care and have lower health care costs than their U.S.-born counterparts, reflecting that they are younger and healthier and that they face greater barriers to care. Data also show that undocumented immigrants contribute billions in federal, state, and local taxes, with a sizeable share going toward programs that they cannot access, like Social Security and Medicare, and that they help subsidize health care for U.S.-born citizens