One Year After the Storm: Texas Gulf Coast Residents’ Views and Experiences with Hurricane Harvey Recovery

Section 1: Recovery Experiences Among Residents Affected by Harvey

The Big Picture: How Are Those Affected by Harvey Faring Nearly One Year After the Storm?

For purposes of this report, residents who were “affected by Hurricane Harvey” are defined as those who say they incurred damage to their home or vehicle, or that they or someone in their household lost a job, had hours cut back at work, or experienced some other loss of income as a result of Harvey. Overall, six in ten (58 percent) residents of the 24 counties surveyed say they experienced one of these things, a share that is slightly lower than the share who reported these experiences in the first survey three months after the storm, mostly due to a lower share reporting employment disruptions. Consistent with the results of the earlier survey, Black and Hispanic residents, those with lower incomes, and those living in the Golden Triangle and Coastal Counties are more likely to report being affected by the hurricane (see Appendix B for more information).

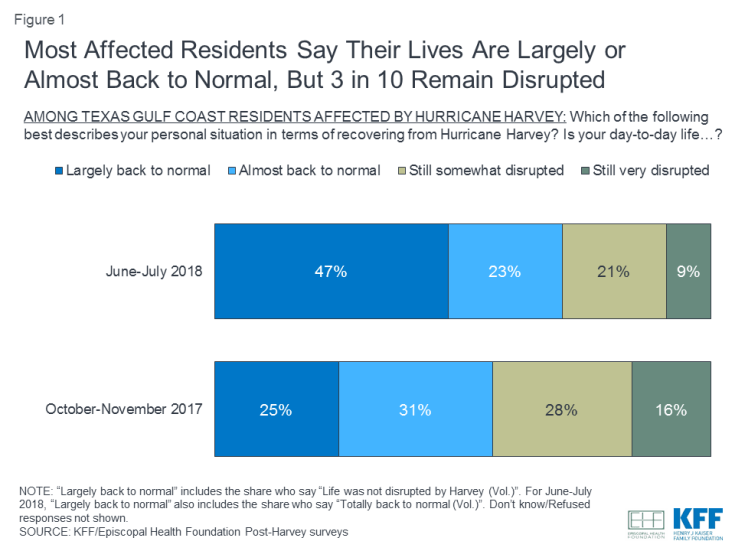

Among those who were affected by the storm, many report significant progress in getting their lives back on track. Overall, 70 percent of affected residents say their lives are “largely” or “almost” back to normal, a share that is up from 56 percent eight months ago. Still, three in ten affected residents say their lives are still “very” or “somewhat” disrupted from the storm.

Figure 1: Most Affected Residents Say Their Lives Are Largely or Almost Back to Normal, But 3 in 10 Remain Disrupted

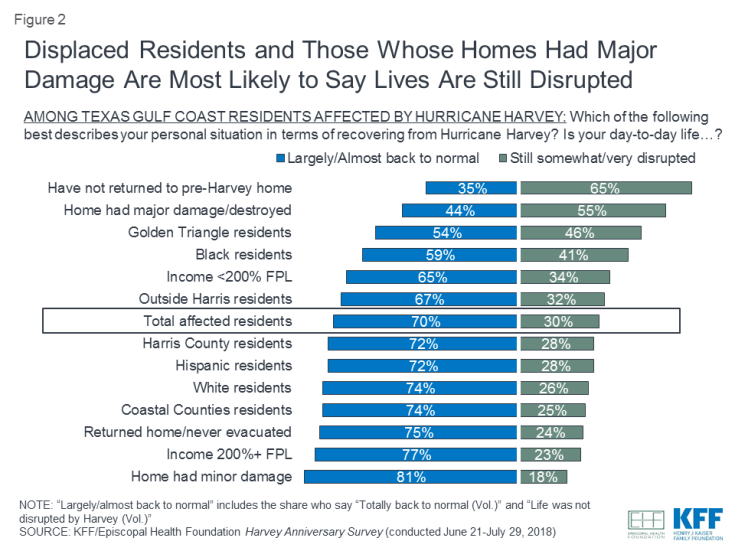

The share reporting that their lives are still disrupted nearly one year after Harvey is highest among two groups: 1) those who evacuated their homes and are still living somewhere different today, a group that represents 8 percent of the total area population and among whom 65 percent say their lives are still disrupted; and 2) those who say their home sustained major damage or was destroyed, representing 19 percent of the total population, with 55 percent saying their lives are still disrupted. These groups, which overlap somewhat but not completely, report higher levels of disruption along a number of dimensions measured in the survey, and key findings for each group are highlighted in a special section below. In addition to these two groups, affected residents who are Black, living in the Golden Triangle area, or have lower incomes are more likely than their counterparts to report that their lives are still disrupted due to the effects of Harvey.

Figure 2: Displaced Residents and Those Whose Homes Had Major Damage Are Most Likely to Say Lives Are Still Disrupted

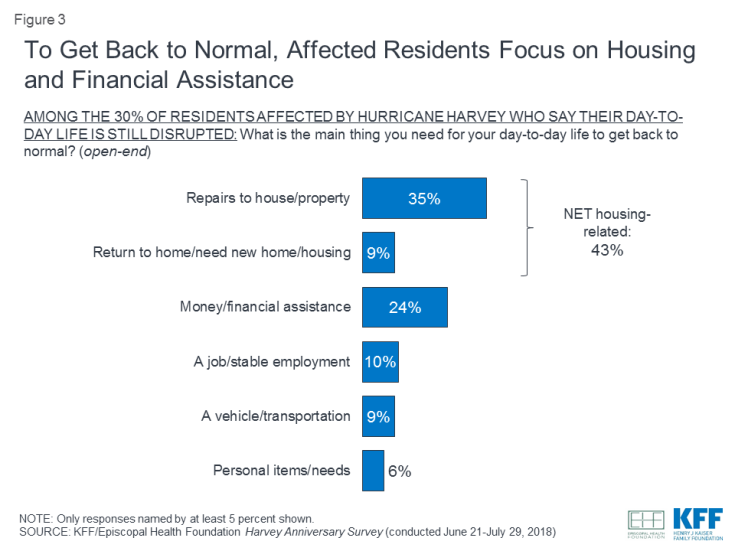

When the 30 percent of Harvey-affected residents who say their lives are still disrupted are asked to name in their own words the main thing they need for their day-to-day life to return to normal, responses focus on basic needs like home repairs, financial assistance, employment, and transportation. Four in ten (43 percent) mention housing-related issues, including 35 percent who say the main thing they need is for their home to be repaired and 9 percent who say they need to be able to return to their home or find new housing. One-quarter (24 percent) say their biggest need is money or financial assistance, and about one in ten each say they need a job or stable employment (10 percent), or a vehicle or other form of transportation (9 percent).

Focus group highlight: Ongoing areas of need

Focus group participants were asked about the problems they currently face and potential solutions in three specific areas: housing, employment, and physical and mental health. Counts of mentions during related group exercises are detailed in Appendix C. Consistent with the survey results, focus group participants stressed the need to make repairs to their home or find a new place to live, and the importance of financial help to make these things happen. For many focus group participants, loss of a vehicle due to Harvey was linked to their ability to work, which in turn is linked to their ability to restore their homes to a livable condition, illustrating how multiple impacts on an individual can contribute to a cycle that makes recovery very difficult.

“We lost both cars. My husband lost his tools. We’re still living with another family. They are 3, we’re 4. It’s 2 rooms. We’re sleeping in the living room. But my husband, he still has not been able to recover his tools. He’s still doing odd jobs here and there. We don’t have enough to go back to an apartment.” – 32-year-old undocumented Hispanic female, Houston

“I lost a vehicle. I lost my way to work. They weren’t too big on coming and picking me up. I’ve been trying to find work. Right now it’s slow. I’m getting way behind on my child support and everything. It’s been bad.” – 29-year-old white male, Dickinson

“I didn’t have a rig truck [so] I couldn’t go to work. Then I did try to file for unemployment and they said that I quit. The company said that I quit because I didn’t have a truck to come to work no more.” – 34-year-old white male, Dickinson

“We just need people to help us, period. Because you’ll call these organizations and nobody still not gonna return no calls until a month or two later. Still no answer.” – 27-year-old Black female, Port Arthur

“Once this left the front page, we became yesterday’s news. As long as it’s on the front page, you had everybody coming down wanting to help poor little old Port Arthur. But once it left the front page, then you’re expected to be back to normal at that point. And it’s not so.” – 59-year-old Black male, Port Arthur

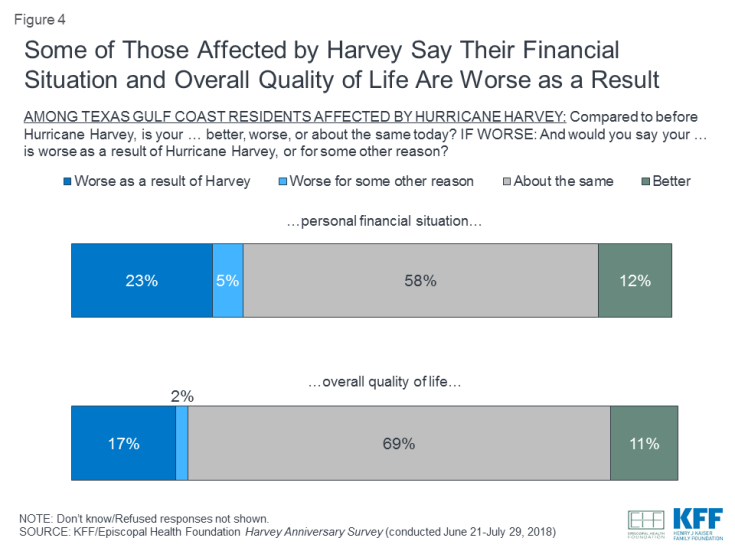

In another sign that many families are well on their way to recovery, most residents who were affected by Harvey report that their personal financial situation and their overall quality of life are about the same as they were before the storm. However, about three in ten affected residents say their current financial situation is worse than it was before the storm, including 23 percent who attribute the decline directly to Hurricane Harvey. Similarly, 17 percent of those who were affected say their overall quality of life is worse now as a result of the storm.

Figure 4: Some of Those Affected by Harvey Say Their Financial Situation and Overall Quality of Life Are Worse as a Result

Black residents and those living in the hard-hit Golden Triangle area are more likely than others to report declines in their financial situation and quality of life due to Harvey. About a third of each of these groups say things are worse on each of these dimensions.

| Table 1: Affected Residents’ Financial Situation and Overall Quality of Life After Hurricane Harvey | ||||||||||

| AMONG TEXAS GULF COAST RESIDENTS AFFECTED BY HURRICANE HARVEY: Percent who say their ____ is worse today as a result of Hurricane Harvey: |

Total | Geographic Region | Race/Ethnicity | Self-reported Income (% of FPL) |

||||||

| Harris County | Outside Harris | Golden Triangle | Coastal | White | Hispanic | Black | <200% | 200%+ | ||

| Personal financial situation | 23% | 22% | 23% | 34% | 22% | 25% | 17% | 31% | 24% | 22% |

| Overall quality of life | 17 | 17 | 17 | 32 | 13 | 18 | 11 | 31 | 20 | 14 |

Do Affected Residents Feel They Are Getting the Help They Need?

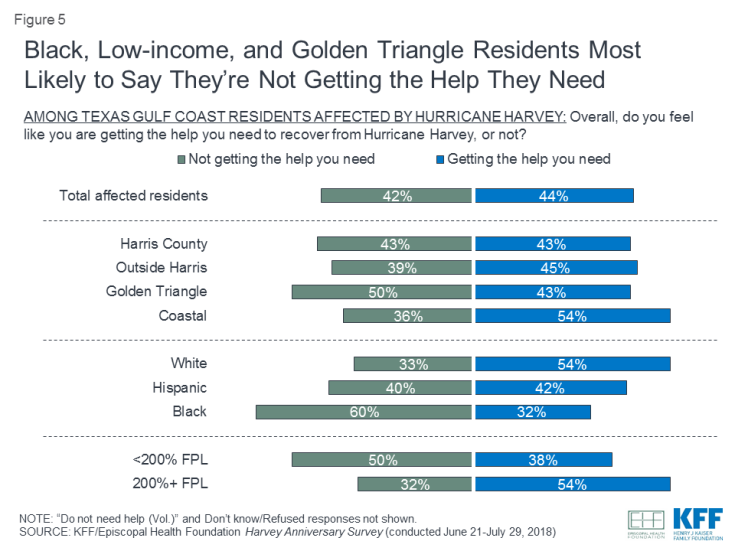

Ten months after Hurricane Harvey hit, four in ten affected residents (42 percent) say they are not getting the help they need to recover from the storm, roughly the same share who said so in the previous survey conducted three months after Harvey (45 percent). Notably, among those affected by the storm, six in ten Black residents, half of those living in the Golden Triangle, and half of those with self-reported incomes below 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) say they are not getting the help they need.

Figure 5: Black, Low-income, and Golden Triangle Residents Most Likely to Say They’re Not Getting the Help They Need

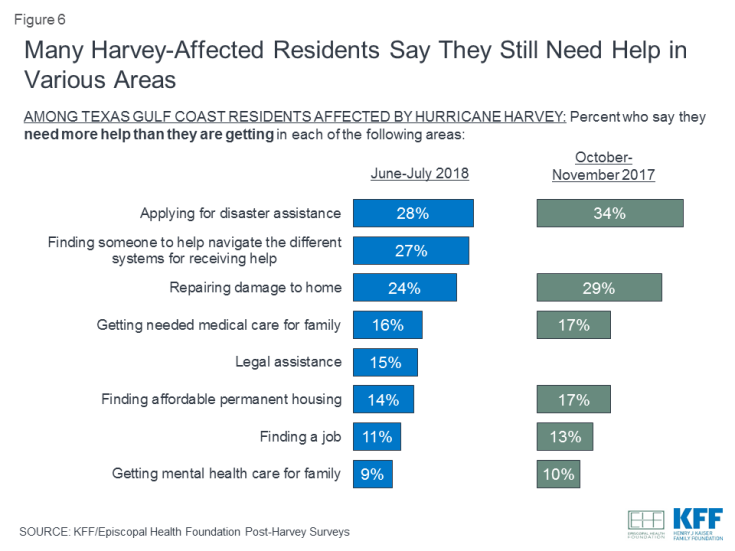

When it comes to the specific areas in which people affected by Harvey say they need more help, navigating the systems for receiving aid remains a big area of need. About three in ten affected residents (28 percent) say they need more help applying for disaster assistance, a share that has declined only slightly from the three-month mark (34 percent). A similar share (27 percent) say they need help navigating the different systems for receiving aid, and 15 percent say they need help with legal assistance.

The shares of affected residents who say they need more help repairing damage to their homes (24 percent), finding affordable housing (14 percent), finding a job (11 percent), and getting medical care (16 percent) and mental health care (9 percent) have remained at similar levels since the first survey, suggesting that help has been slow to come to those most in need.

Focus group highlight: Confusion over how to get financial help

The themes of confusion and a need for help with applying for disaster assistance were commonly raised in the focus groups.

“Maybe openly have some people to kind of coach them through where to go. I see some households … they didn’t know where to go or what to do. What’s next? They have no idea, especially older people, single people, they just gave up. … Go to them and say hey, ‘We’re not asking to work against FEMA,’ but say, ‘This is how their system works. This is what you have to do to get to where you got to do.’ I don’t know. Help people take the next step.” – 34-year-old white male, Dickinson

“I immediately did the application for help for the house. I had house insurance but not flood insurance. I didn’t know there were two separate insurances that you had to buy.” – 55-year-old Hispanic female, Houston

“Any time I heard about any help, it had already elapsed. It was over. I didn’t hear about this.” – white female, Dickinson

“FEMA was like just a lot of unnecessary hoops that they make you jump through, right after an emergency … Like you have to have so much paperwork for anything. And a lot of it I didn’t have … The whole entire place flooded. I don’t have any copies of anything because they were destroyed.” – 26-year-old Black female, Dickinson

Serious Housing Issues Remain a Problem for Some Residents

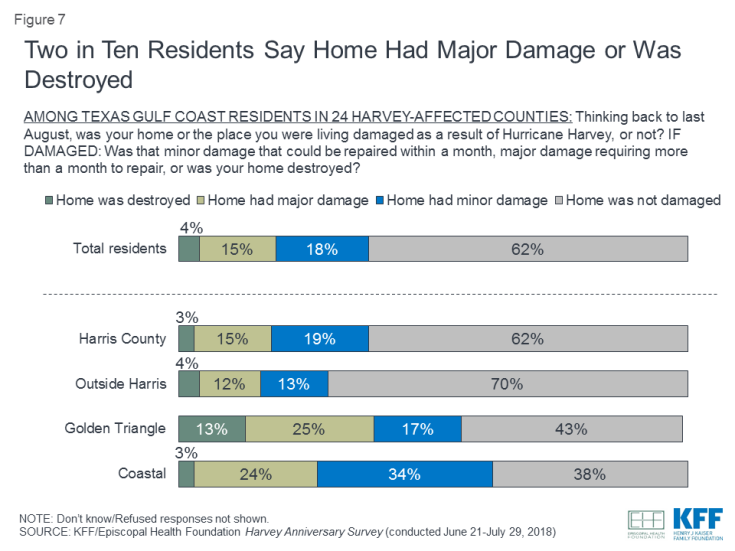

While many Texas Gulf Coast residents report being well on the road to recovery from Harvey, serious housing issues remain a problem for others. As noted above, 19 percent of all 24-county area residents say that their home sustained major damage or was destroyed as a result of Harvey, a share that rises to 27 percent in the Coastal area and 38 percent in the Golden Triangle.

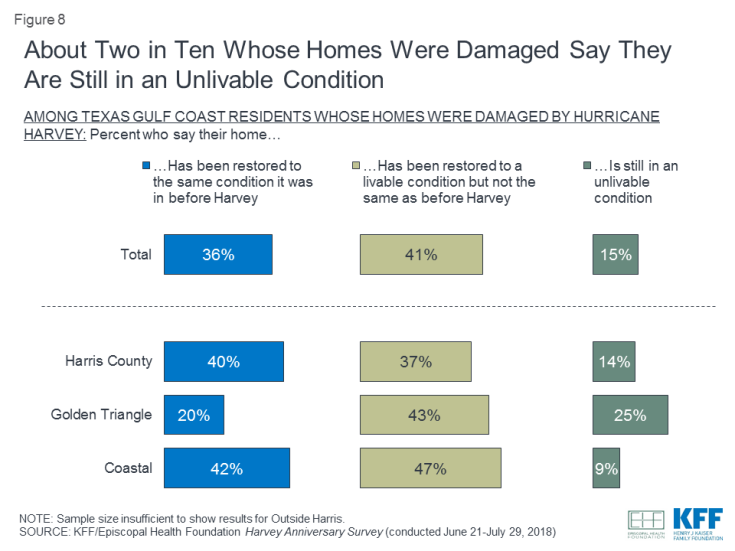

Among those who sustained any damage to their home as a result of Harvey, about a third (36 percent) say their home has been restored to the same condition it was in before the storm, while four in ten (41 percent) say it has been restored to a livable condition but not the same as it was before Harvey. One in six (15 percent) of those residents who experienced home damage say their home is still in an unlivable condition 10 months later, a share that rises to 25 percent among Golden Triangle residents whose homes were damaged.

Among those whose homes have not been restored to the same or better condition they were in before Harvey, the largest share (51 percent) say the reason is that they could not afford the cost of the repairs, while 11 percent say they are waiting for insurance money or other financial help to come through, 10 percent are renters who say their landlord has not completed work, and 6 percent say they’ve been unable to find someone to help them do the necessary work on their home.

Focus group highlight: Challenges related to home repairs

For focus group participants who are still struggling to repair damage to their homes, most mentioned lack of money as a major barrier to being able to complete the work, while others mentioned difficulty finding contractors. Several participants said that the easy part of the work (demolition, basic sheetrock installation) had been done with volunteers, but that the remainder of the work (roofing, floors) required professional help that they couldn’t afford.

“Contractors have been like at a premium. You find a contractor and he says, ‘I can get to you in 3 months.’” – 59-year-old Black male, Port Arthur

“I even found a contractor I liked but I didn’t have the funds to make use of him, you know?” – 47-year-old white male, Dickinson

“We can fix this and fix that. It’s hard to get people to help. That’s the way we fixed the walls. Between my children, my son-in-laws, we [knocked] down walls and we use that money. My issue … is the foundation and the roof. The roof and the foundation has to be a professional.” – 55-year-old Hispanic female, Houston

“The roof guy is gonna put the tiles and with the materials [for $4000]? That’s a good price.” – 34-year-old Hispanic male, Houston

“[Responding to above comment] But I don’t have the $4000. That’s the issue. The thing is there’s no money.” – 55-year-old Hispanic female, Houston

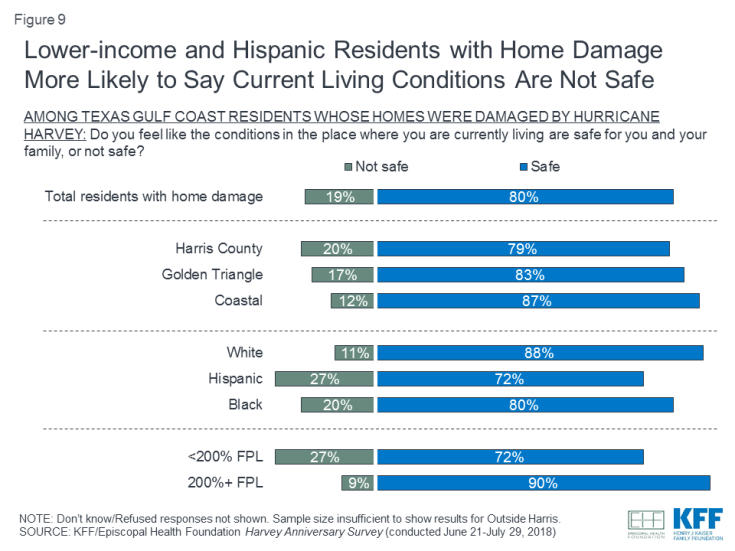

In addition, about one in five (19 percent) of those whose homes were damaged by Harvey (representing 7 percent of all residents in the 24-county area) say that the conditions in the place where they are currently living are not safe for them and their families. Notably, lower-income and Hispanic residents with home damage are more likely than others to say their current living conditions are not safe.

Figure 9: Lower-income and Hispanic Residents with Home Damage More Likely to Say Current Living Conditions Are Not Safe

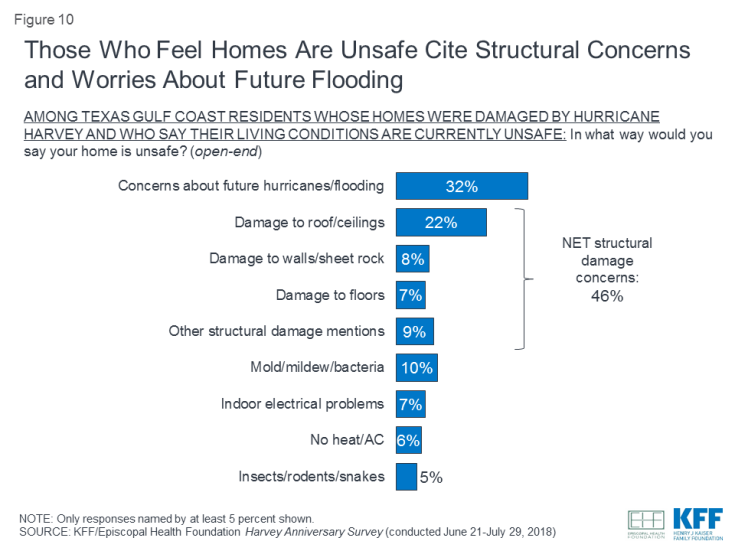

Among those who feel their living conditions are not safe, about a third (32 percent) say their concern is related to the potential of their home to withstand future storms or flooding, while nearly half (46 percent) mention structural concern such as damage to their roof or ceilings (22 percent), walls or sheetrock (8 percent), floors (7 percent) or other structural damage (9 percent). One in ten (10 percent) of those who feel unsafe say their concern is related to the presence of mold, mildew, or bacteria, while 6 percent say they are living without heat or air conditioning (a potentially major concern in the hot Texas summer), and 5 percent are worried about the presence of insects, snakes, or rodents in their home.

Figure 10: Those Who Feel Homes Are Unsafe Cite Structural Concerns and Worries About Future Flooding

Focus group highlight: Safety of living conditions

Focus group participants who felt unsafe in their homes mostly reported that they didn’t have anywhere else to go. Others said they weren’t necessarily comfortable living in an unfinished house or apartment, but that they were getting used to it and accepting their situation.

“[Moderator: Is the house you’re renting safe?] No, but I ain’t got nowhere else to go.” – 47-year-old Black male, Port Arthur

“I had to stay in my home because I had nowhere to go. I had nowhere to go until it burned down while I was in it. [A fire] burned my house down. It was an electrical fire … I was living in mold. I was living with my floors falling through. I was living with my ceiling falling through.” – white female, Dickinson

“[Still don’t feel safe] because we’re in hurricane season again. I have no sheetrock. I have no insulation in my house and creepy crawly bugs and things like that and I hear stuff at night … I’m not happy. Let me put it like this: I’m not comfortable, but it is what it is. I want it to get better. I’m doing what I can.” – 65-year-old Black female, Port Arthur

“It’s not complete so it’s not up to standard, but like [other participant] said you get used to it, you know, until you can do better.” – 60-year-old Black female, Dickinson

Spotlight on Those with Severe Home Damage

The 19 percent of Texas Gulf Coast residents who experienced major damage or destruction of their home are one of the groups most likely to report continued disruptions to their lives nearly one year after the storm. Similar to other groups, six in ten of these individuals (59 percent) were homeowners and four in ten (39 percent) were renters at the time Harvey hit. Just a quarter (25 percent) say they had flood insurance and about half (53 percent) had homeowners’ or renters’ insurance at the time of the storm.

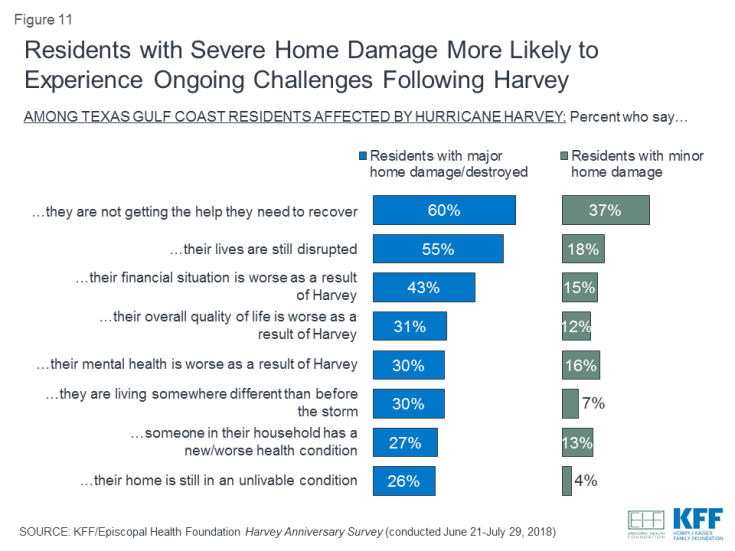

Those who experienced major home damage have had a much tougher road to recovery in the nearly one year since the storm. They are three times as likely as those who had only minor home damage to say their lives are still disrupted (55 percent versus 18 percent). Fully six in ten say they are not getting the help they need to recover from the storm, compared to 37 percent of those with minor home damage. They are also much more likely than their counterparts to report disruptions to their finances, physical and mental health, and well-being. Four in ten (43 percent) say their personal financial situation is worse as a result of Harvey, and 31 percent say the same about their overall quality of life. Three in ten say their own mental health is worse as a result of the storm, and nearly as many (27 percent) say that someone in their household has a health condition that is new or worse because of Harvey. Thirty percent are living somewhere different than before the storm, and one quarter (26 percent) report that their home remains in an unlivable condition.

Figure 11: Residents with Severe Home Damage More Likely to Experience Ongoing Challenges Following Harvey

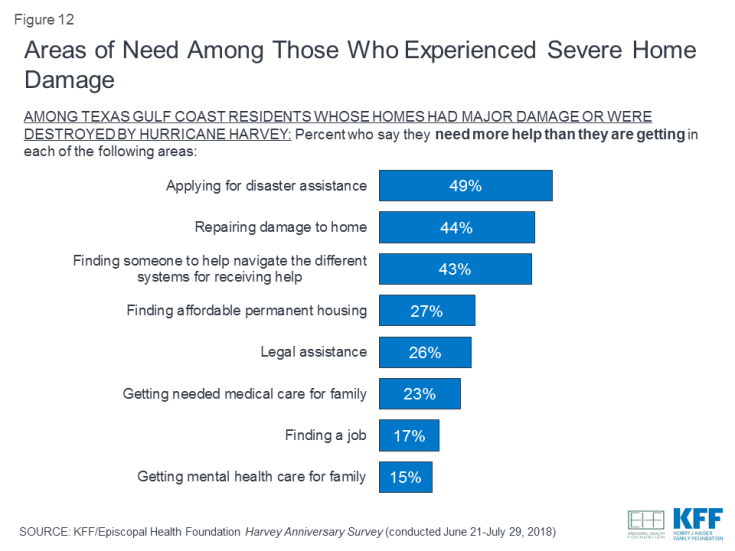

Those who report major damage or destruction to their homes are also more likely than others to report needing help in a variety of areas. About half (49 percent) say they need help applying for disaster assistance and more than four in ten need help repairing damage to their homes (44 percent) or navigating the different systems for receiving aid (43 percent). About a quarter also say they need help finding affordable housing (27 percent) and getting legal assistance (26 percent), and many also say they need more help getting medical care (23 percent), finding a job (17 percent), or getting mental health care (15 percent) for themselves or a family member.

Spotlight on Those Who Evacuated and Have Not Returned to Pre-Harvey Home

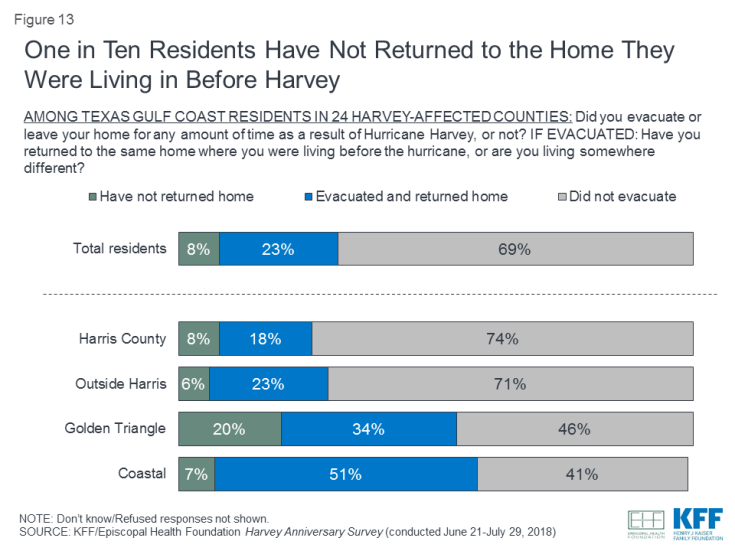

While most residents who evacuated during Harvey have been able to return to their homes, 8 percent of all residents in the 24-county area say they evacuated and have not returned to the same place they were living before the storm, rising to 20 percent in the Golden Triangle area. Seven in ten (69 percent) of affected residents who have not returned to their original home say they were renting the place they lived in before Harvey, and four in ten (38 percent) report having incomes below the poverty level. The large majority (75 percent) of this group say their home sustained major damage or was destroyed, but 23 percent say they had only minor or no damage, suggesting that issues beyond just structural damage – such as financial issues and problems with landlords – may have prevented some of these individuals from returning to their pre-Harvey homes.

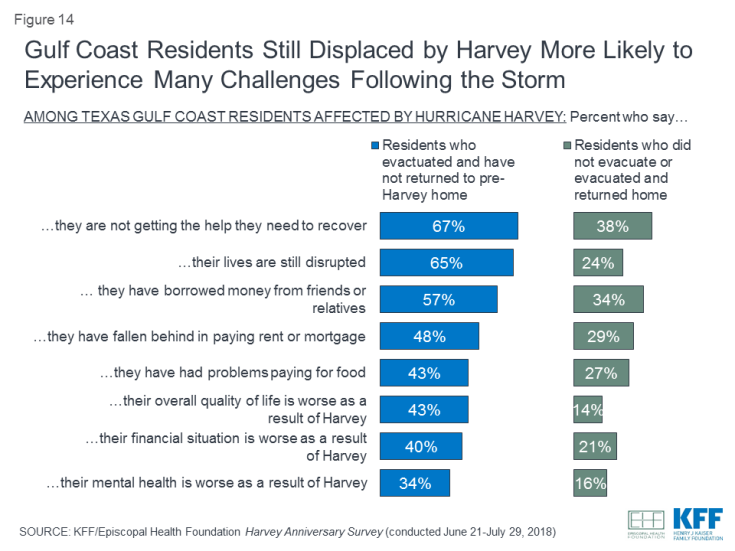

Like the group who experienced major home damage, affected residents who were displaced from their homes by Harvey report experiencing more severe disruptions than others who were affected by the storm. Two-thirds (65 percent) say their lives are still disrupted by Harvey nearly one year later, and a similar share (67 percent) say they’re not getting the help they need to recover. This group also reports a variety of financial problems in the wake of the storm. Nearly six in ten (57 percent) say that since Harvey they’ve had to borrow money from friends or relatives to make ends meet, about half (48 percent) say they’ve fallen behind in paying their rent or mortgage, and four in ten (43 percent) report problems paying for food. Four in ten say both their overall quality of life (43 percent) and their personal financial situation (40 percent) are worse as a result of Harvey, while about a third (34 percent) say their mental health is worse.

Figure 14: Gulf Coast Residents Still Displaced by Harvey More Likely to Experience Many Challenges Following the Storm

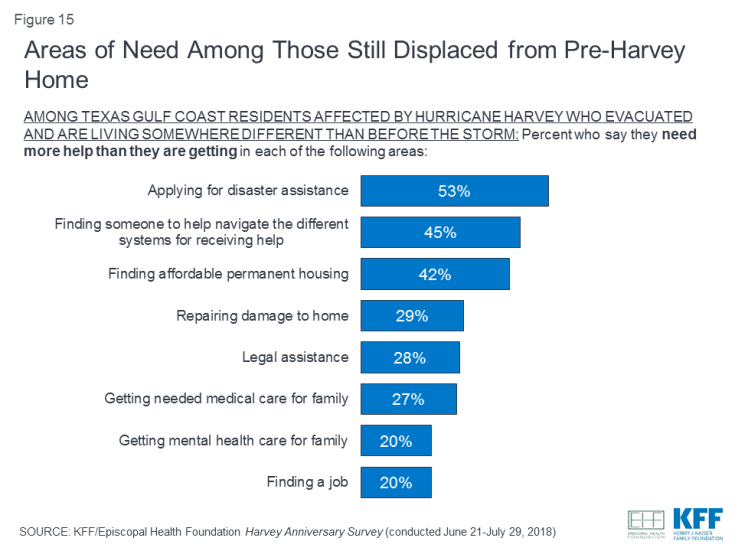

For affected residents who have not been able to return to their pre-Harvey home, the biggest areas of need are applying for disaster assistance (53 percent say they need more help), finding someone to help navigate the different systems for receiving aid (45 percent), and finding affordable permanent housing (42 percent).

Financial Help and Financial Problems Among Those Affected by Harvey

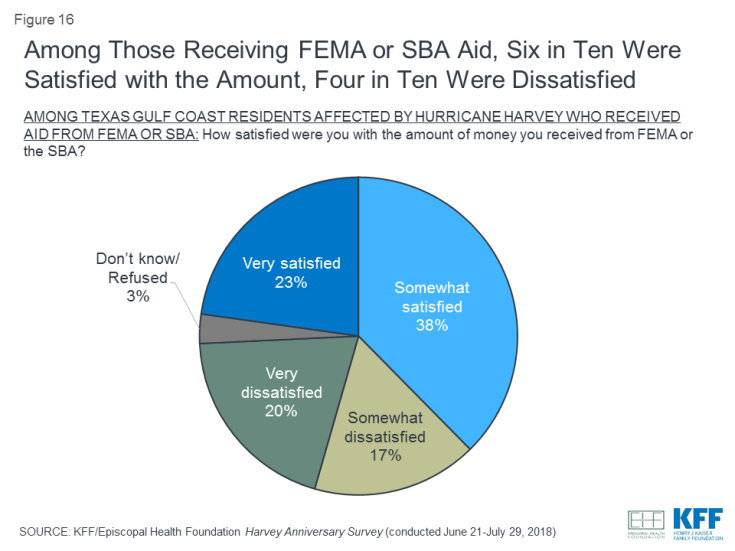

Among Texas Gulf Coast residents who were affected by Hurricane Harvey, four in ten (41 percent) say they applied for disaster assistance from FEMA or the SBA. Of these, four in ten (39 percent) say their application was approved and a similar share (42 percent) say it was denied. While the overall share receiving aid from FEMA or the SBA is small (16 percent of all affected residents), most (60 percent) of those who received this aid say they were satisfied with the amount of money they received, though almost four in ten (37 percent) say they were dissatisfied.

Figure 16: Among Those Receiving FEMA or SBA Aid, Six in Ten Were Satisfied with the Amount, Four in Ten Were Dissatisfied

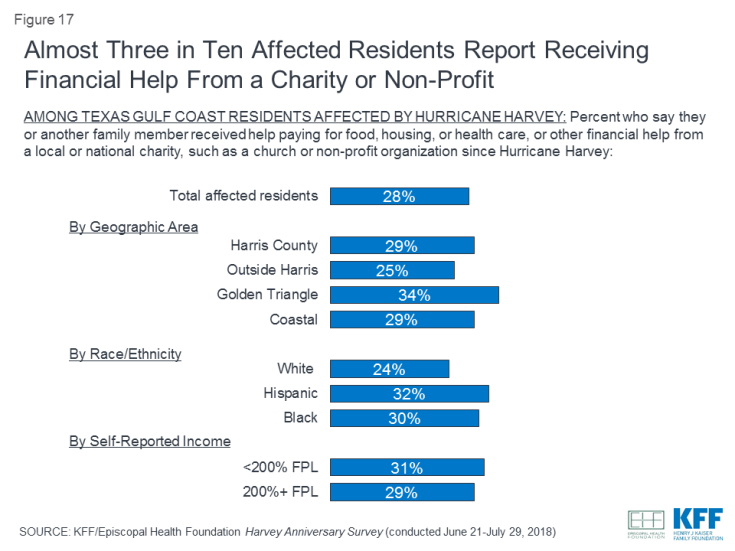

In addition to federal disaster assistance, about three in ten (28 percent) of affected residents say they have received help paying for food, housing, or health care, or some other type of financial help from a local or national charity since Hurricane Harvey. Hispanic residents are somewhat more likely than white residents to report receiving such help (32 percent versus 24 percent), but otherwise the share who received help doesn’t differ substantially by race, income, or geography.

Figure 17: Almost Three in Ten Affected Residents Report Receiving Financial Help From a Charity or Non-Profit

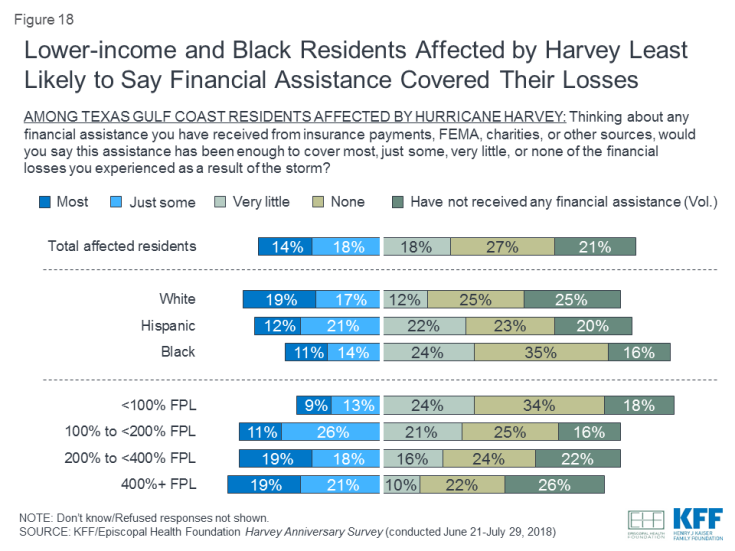

Despite receiving aid from various sources, most residents who were affected by Harvey do not feel this help will be enough to cover the majority of their financial losses from the storm. Taking into account all sources of financial help including insurance payments, disaster aid, and help from charities, most affected residents (66 percent) say this assistance will cover very little (18 percent) or none (27 percent) of the financial losses they experienced as a result of the storm, or that they haven’t received any type of financial help or payments (21 percent). Just 14 percent say such payments will cover most of their financial losses and another 18 percent say they will cover “just some.” Black residents and those with the lowest incomes are the least likely to say that most or some of their losses will be covered by insurance payments and financial aid.

Figure 18: Lower-income and Black Residents Affected by Harvey Least Likely to Say Financial Assistance Covered Their Losses

Focus group highlight: Financial help and financial problems

Quotes from focus group participants highlight the multiple financial problems residents faced in the wake of the hurricane, and the fact that any aid they received was inadequate to cover the costs they were facing.

“I had 2 jobs when I was pregnant and I was looking for homes to clean. I was cleaning night and day. We had our things. I had a car and everything, and all of a sudden you don’t even have clothes to put on. Living in an apartment, I started thinking, ‘I work so much and I don’t have anything.’” – 32-year-old undocumented Hispanic female, Houston

“Even with the assistance … In my case we were driving back and forth from Winnie. It was the gas, the food. I mean you’re exhausted. You’re on the road trying to survive.” – 53-year-old Black female, Port Arthur

“Well I had to fight them because I lost everything. I had to send them pictures and everything I had because they felt that what I owned was only worth $2000, and I worked all my life for those things. Although they were material, but they were mine. So I had to fight them in order to get what I got from them.” – 53-year-old Black female, Port Arthur

“So the people they sent from FEMA … They would inspect and say, ‘Oh you can fix this with $4,000.’ But they didn’t go to Home Depot to see how much they were charging for sheetrock. They didn’t know the cost of materials.” – 49-year-old undocumented Hispanic female, Houston

“I did get several [bids from contractors], anywhere from $60,000 to $80,000 or more. And the amount that I got from FEMA was not even close. So I stretched it out as far as I could, to take care of home repairs, as well as trying to replace a vehicle, because my vehicle was flooded. And I’ve charged up credit cards as well and pulled money from savings accounts which I’ll probably be taxed on, and my house is still not finished.” – 60-year-old Black female, Dickinson

Affected residents report a variety of financial problems since Harvey. About four in ten (38 percent) say they or someone else in their household has taken on an extra job or worked extra hours since the storm in order to make ends meet, and a similar share (27 percent) say they have borrowed money from friends or relatives. One-third (32 percent) say they have fallen behind in paying their rent or mortgage and three in ten (29 percent) report having problems paying for food. Six in ten (62 percent) of affected residents report at least one of these problems. As Table 2 shows, reported financial problems in the wake of Hurricane Harvey are much more common among affected residents with lower self-reported incomes, as well as among Black and Hispanic residents.

Figure 19: Six in Ten Harvey-Affected Residents Report Experiencing Financial Problems Since the Storm

| Table 2: Reported Financial Challenges of Residents Affected by Hurricane Harvey | ||||||||

| AMONG TEXAS GULF COAST RESIDENTS AFFECTED BY HURRICANE HARVEY: Percent who say they or any other adult in their household have ____ since Hurricane Harvey hit: |

Total | Self-reported Income (% of FPL) | Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| <100% | 100% to <200% | 200% to <400% | 400%+ | White | Hispanic | Black | ||

| Borrowed money from friends or relatives to make ends meet | 37% | 47% | 45% | 35% | 10% | 28% | 38% | 49% |

| Taken on an extra job or worked extra hours to make ends meet | 38 | 41 | 46 | 36 | 24 | 36 | 35 | 43 |

| Fallen behind in paying their rent or mortgage | 32 | 44 | 38 | 25 | 10 | 20 | 40 | 39 |

| Had problems paying for food | 29 | 43 | 35 | 21 | 5 | 22 | 30 | 39 |

| Experienced any of the above problems | 62 | 74 | 70 | 59 | 32 | 51 | 64 | 75 |

Health, Mental Health, and Resilience

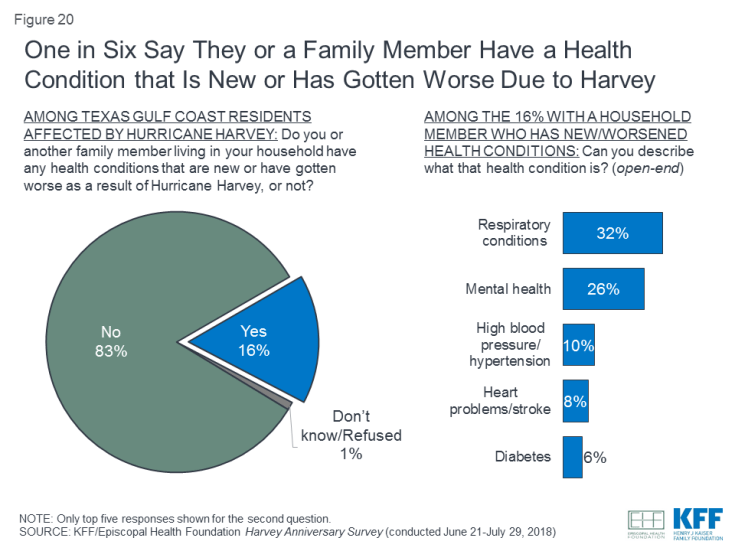

Beyond impacts on their housing, employment, and financial situations, some residents report problems with their physical and/or mental health as a result of Hurricane Harvey. Overall, 16 percent of affected residents say they or someone in their household has a health condition that is new or has gotten worse since Harvey. This is similar to the share of affected residents who reported a new or worse health condition in the first survey (17 percent), suggesting that most health effects from the storm began in the early months and many have persisted since then. The most commonly reported health conditions are respiratory problems such as asthma, coughing, or other breathing problems (32 percent of those reporting a health condition), followed by mental health issues like depression and anxiety (26 percent), high blood pressure (10 percent), cardiovascular problems (8 percent), and diabetes (6 percent).

Figure 20: One in Six Say They or a Family Member Have a Health Condition that Is New or Has Gotten Worse Due to Harvey

Residents who were affected by Harvey also report a variety of mental health consequences from the hurricane. About three in ten (31 percent) of affected residents report some negative effect on their mental health, including having a harder time controlling temper (19 percent), feeling their mental health has gotten worse (18 percent), taking a new prescription for a mental health issue (10 percent), or increasing their alcohol use because of Harvey (6 percent). Again, these shares are similar to those reported by affected residents in the first survey (32 percent reported at least one of these problems), suggesting that on balance, there has not been a marked improvement or a further decline in mental health issues among residents who began to feel these effects in the immediate aftermath of the storm.

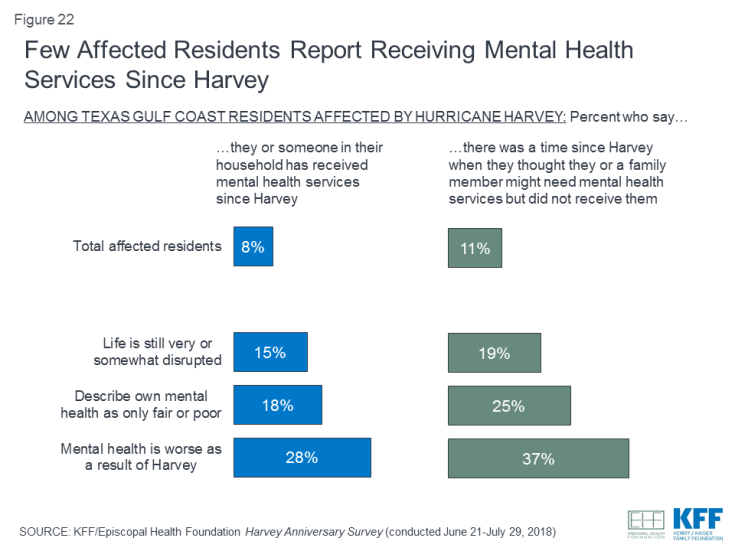

Despite the relative prevalence of self-reported mental health problems among residents affected by Harvey, few (8 percent) say that they or someone in their household has received any mental health services since the storm, including just 5 percent who say someone received these services related to their experience with Harvey. A similarly small share (11 percent) say there was a time since the hurricane when they thought they or a family member might need mental health services but did not receive them. While these shares are small among affected residents overall, they are somewhat higher among those who say their lives are still disrupted from the storm, those who describe their own mental health as only fair or poor, and those who feel that their mental health has gotten worse as a result of Harvey.

Among those who say there was a time since Harvey when they or a family member did not receive mental health services they thought they might need, half say the main reason was that they could not afford the cost (47 percent), while nearly as many say they did not seek out the services (39 percent).

Residents of the Golden Triangle area are more likely than those living in other areas to report negative mental health consequences as a result of Hurricane Harvey, particularly due to the fact that a larger share of these residents say they have had a harder time controlling their temper since the storm. However, Golden Triangle residents are not more likely than others to report that someone in their household has received any mental health services since the storm. Notably, Hispanic residents are less likely than both white and Black residents to report declines in their mental health due to Harvey, and less likely to say that someone in their household has received counseling or other mental health services.

| Table 3: Affected Residents’ Mental Health After Hurricane Harvey | |||||||||||

|

AMONG TEXAS GULF COAST RESIDENTS AFFECTED BY HURRICANE HARVEY: |

Total | Geographic Region | Race/Ethnicity | Self-reported Income (% of FPL) |

|||||||

| Harris County | Outside Harris | Golden Triangle | Coastal | White | Hispanic | Black | <200% | 200%+ | |||

| Have had a harder time controlling temper | 19% | 21% | 16% | 27% | 16% | 20% | 14% | 28% | 22% | 17% | |

| Mental health has gotten worse as a result of Harvey | 18 | 20 | 15 | 23 | 16 | 20 | 14 | 25 | 22 | 15 | |

| Started taking a new prescription medicine for problems with mental health | 10 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 14 | 12 | 8 | |

| Increased alcohol use because of Harvey | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 11 | 7 | 3 | |

| Experienced any of the above problems | 31 | 32 | 26 | 42 | 31 | 34 | 24 | 37 | 34 | 29 | |

| Percent who say they or another family member in their household received mental health services since Harvey | 8 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 13 | 10 | 7 | |

Focus group highlight: Mental health challenges and services

Focus group participants were chosen to represent one of the hardest-hit groups: those who say their lives are still disrupted nearly one year after the hurricane. The emotions expressed in the groups were often intense, with issues of stress, anxiety, anger, and depression being raised in each group. For some, this stress was a reaction to the physical and financial challenges associated with recovery, while for others, stress was triggered by the difficulty of navigating the processes for receiving financial help. Several participants mentioned the need for better support systems to connect those who are still struggling to piece their lives together.

“Depression … the everyday life after Harvey – like it stopped, for a lot of us. We pick ourselves back up. It’s hard, it’s frustrating, and it’s also depressing.” – 29-year-old Hispanic female, Houston

“Material damages? [Those can be fixed in] two or three years. But emotional? It’s something that you could have to live with for your whole life.” – 37-year-old undocumented Hispanic male, Houston

“I was angry as all hell [about the process for receiving assistance]. I’m not going to lie to you. I’m not going to act out on anybody, but when I see these agencies email you back saying, ‘Come over here and sign up again for Red Cross.’ They’re now doing a $2,000 payment. They did it again, nothing.” – white male, Dickinson

“I think support systems are good. I’m not talking about family. I’m talking about being able to go and talk with people that may be able to help – with not everything, but some things. Sometimes all you’ve got to do is go in to talk to somebody that’s willing to listen. ” – 65-year-old Black female, Port Arthur

“I’m a pretty functional individual, but you know what? This has pulled the rug from under me. I watched them do this to other people. I said this lady is totally exhausted. We really need some prepared people for mental health. I think we’re starting to see it in many avenues. But there are a lot of exhausted people that are still not home.” – 55-year-old Black female, Dickinson

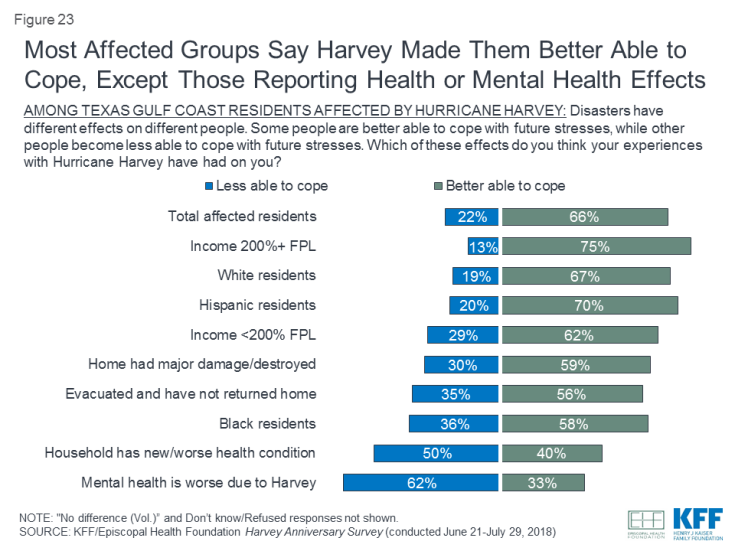

Living through a disaster can have varying effects on the resilience of individuals and communities. While much research on disaster resilience is conducted at the community level, measuring individuals’ self-reported sense of resilience can also be illuminating. For example, ten years after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, most city residents who had lived through the storm felt that the experience had made them better able to cope with future stresses rather than less able to cope.1 The current survey finds a similar situation among Texas Gulf Coast residents affected by Hurricane Harvey – 66 percent say their experiences with the storm have made them better able to cope, while 22 percent say these experiences have made them less able to cope.

However, self-reported resilience differs among affected groups, with lower-income residents, Black residents, and those who experienced at least major damage or who remain displaced from their homes more likely than others to say their Harvey experiences have had a negative effect on their resilience (though majorities of all these groups say the experience has made them better able to cope). However, two other groups stand out as reporting more negative than positive impacts on their ability to cope. Among those who say someone in their household has a health condition that is new or worse since Harvey, about half feel their experiences have made them less able to cope with future stresses, while four in ten say they are better able to cope. The difference is even more dramatic among those who say their own mental health is worse as a result of Harvey, with about twice as many saying they feel less able to cope (62 percent) as saying they feel better able to cope (33 percent).

Figure 23: Most Affected Groups Say Harvey Made Them Better Able to Cope, Except Those Reporting Health or Mental Health Effects

Immigration Issues and Harvey Recovery

Immigrants, particularly those who do not have legal resident status in the U.S., may be more vulnerable than others to the effects of natural disasters, and may find it more difficult to seek or obtain the help they need in the aftermath of an event like Hurricane Harvey. The survey finds that immigrants living in the Texas Gulf Coast area who are likely to be undocumented are more likely than either immigrants with legal resident status or native-born residents to report being affected by Hurricane Harvey.2 Specifically, potentially undocumented immigrants are more likely to report that their home was damaged and that someone in their household lost a job, had hours cut back at work, or lost some other form of income as a result of the storm. However, among those who were affected by the storm, there is not a significant difference by immigration status in the share who say their lives are still disrupted or that they are not getting the help they need.

| Table 4: Effects of Hurricane Harvey by Immigration Status | |||

| Potentially Undocumented Immigrants | Immigrants with Legal Resident Status | Native-born Residents | |

| Percent affected by Hurricane Harvey (NET) | 78% | 57% | 56% |

| home was damaged | 49 | 36 | 37 |

| any household member had job/income loss | 69 | 44 | 35 |

| vehicle was damaged | 27 | 19 | 18 |

| AMONG THOSE AFFECTED BY HURRICANE HARVEY: Percent who say… | |||

| …their lives are still disrupted | 30% | 28% | 30% |

| …they are not getting the help they need | 50 | 51 | 39 |

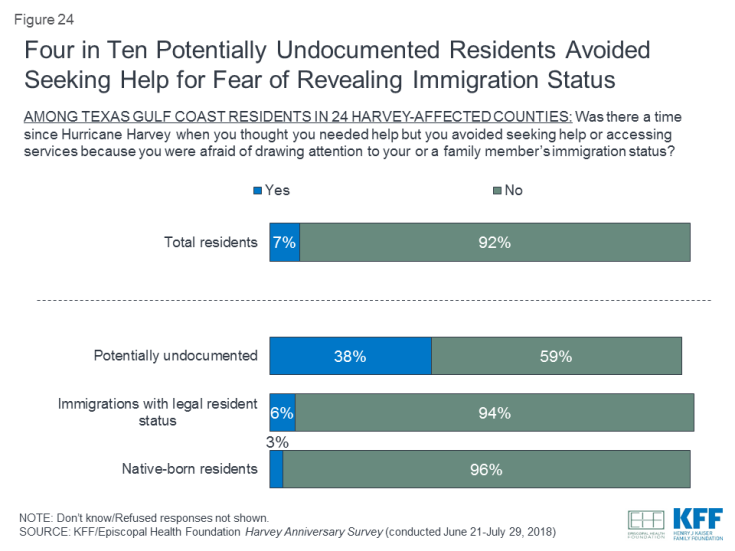

The first survey in this series, conducted three months after Harvey, found that over half of residents who are likely to be undocumented immigrants were worried that if they tried to get help in recovering from the hurricane, they might draw attention to their own immigration status or that of a family member. The current survey took a more direct approach to find out how often these worries are actually preventing people from seeking services they need. Among those who are likely to be undocumented immigrants, nearly four in ten (38 percent) say there was a time since Hurricane Harvey when they thought they needed help but avoided seeking help or accessing services because they were afraid of drawing attention to their own or a family member’s immigration status.

Figure 24: Four in Ten Potentially Undocumented Residents Avoided Seeking Help for Fear of Revealing Immigration Status

Focus group highlight: Immigration issues

The two focus groups held in Houston were conducted in Spanish with individuals who were born outside the United States: one with people who report having legal resident status and one with people who are likely to be undocumented. In both groups, people raised concerns about applying for aid without legal status or a social security number. Several participants also raised concerns about potential employers and others taking advantage of people who are undocumented in a post-disaster situation where people are desperate for work.

“I heard that if you applied without papers or documents, they were registering you or recording you. So I was afraid of that. We were afraid it was like a trap. That they were getting that information to locate you.” – 32-year-old undocumented Hispanic female, Houston

“There are people who offer you work, and then after you finish the job you don’t find them anymore. They don’t pay you. [You need] some kind of protection because they don’t want to pay you. You can’t call the police.” – 56-year-old undocumented Hispanic male, Houston

“They were saying there was gonna be a lot of work after the hurricane, but there were many that didn’t pay. There’s a lot of fraud, lot of jobs that were not paid. [Moderator: A lot of exploitation?] Yea. People were needing work and they saw the opportunity” – 49-year-old undocumented Hispanic female, Houston

“Those car companies are abusing people. Especially with people that don’t have legal documents. You have to be very careful. Since we really need cars, and there are a lot of people who are really abusive. They buy cars that are not in good condition.” – 46-year-old Hispanic female, Houston