Climate Change and Health Equity: Key Questions and Answers

Introduction

Over the past few years, a plethora of research has come out linking climate change to adverse health outcomes around the world. In 2021, a worldwide group of medical research professionals suggested that rising temperatures associated with climate change was the greatest threat to global public health. Illustrating the growing potential consequences of climate change, 2021 marked some of the most frequent extreme and costly climate events in the United States in the past decade. Climate and climate change related health risks disproportionately impact historically marginalized and under-resourced groups, who have the least resources to prepare for and recover from these disasters. As climate-related events become more common, the impacts on health and health care will increase in both frequency and intensity. This brief provides an overview of the impact of climate and climate change on health, identifies who is at increased risk for negative health impacts associated with climate and climate change, explains why there is a growing focus on climate change and health, and reviews recent federal efforts to address climate change and health equity.

How Do Climate and Climate Change Affect Health?

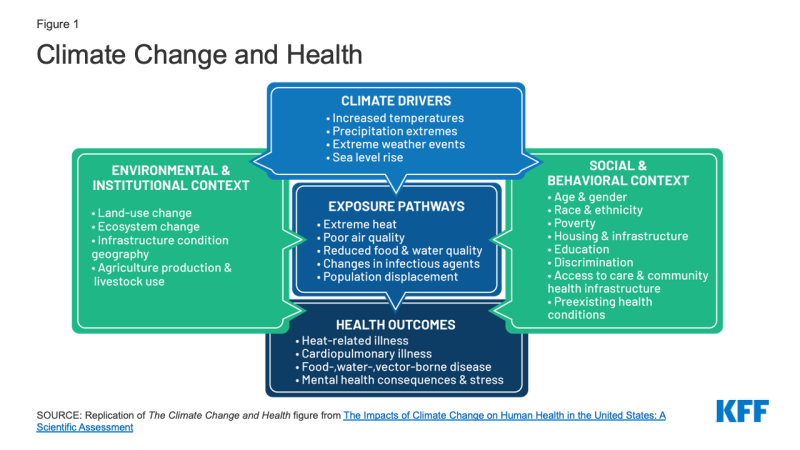

Climate and weather can negatively impact individual and population-level health through multiple pathways. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notes that different climate drivers, including increasing temperatures, precipitation extremes, extreme weather, and rising sea levels, affect health through a range of exposure pathways, including extreme heat, poor air quality, reduced food and water quality, changes in infectious agents, and population displacement (Figure 1). These exposures may lead to negative health outcomes such as heat-related and cardiopulmonary illnesses; food-, water-, and vector-borne diseases, and worsened mental health and stress.

Climate-related health threats are expected to increase going forward. For example:

- Climate change has caused longer, more frequent, and more intense heat waves, which are likely to result in more heat-related illnesses and deaths. Studies have found that exposure to extreme heat makes people sick and may also cause death. In the United States, more than 65,000 people visit the emergency room for heat-related stress and approximately 702 people die from heat exposure each year.

- Increasingly frequent extreme weather events due to climate change cause direct loss of life and negatively impact health through the damage they cause. Over the past twenty years, major storms such as hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Sandy, Harvey, and Maria, have resulted in massive loss of life and billions of dollars of damage. In addition to the immediate hazards created by the storms, the flooding and damage they cause to infrastructure can lead to the spread of waterborne diseases and contamination from industrial and agricultural waste runoff; compromise emergency response efforts; limit access to basic needs, including food, water, and housing; and disrupt access to health care and prescription medications. For example, in a survey of Katrina evacuees in Houston shelters, KFF found that, immediately after the hurricane, 25% of evacuees reported going without needed medical care and about a third (32%) went without their needed prescription medicines. Moreover, impacts extend beyond the immediate aftermath of storms. KFF survey data of New Orleans residents one year after Hurricane Katrina found that 32% said their life remained “very disrupted” or “somewhat disrupted” by the storm, with this share rising to 59% of African American residents in Orleans Parish. More than a third (36%) of those living in the Greater New Orleans area reported their access to health care deteriorated since the storm, 19% reported declines in their physical health, and 16% reported deterioration in their mental health. Ten years after the storm, KFF survey data of New Orleans residents who lived in the area during Katrina reported lingering mental health effects, including problems sleeping. In Puerto Rico, there was an excess mortality of 2,975 deaths as a result of Hurricane Maria. KFF interviews with Puerto Ricans two months after Hurricane Maria found that participants were continuing to face challenges meeting basic needs, and daily life remained challenging due to lack of electricity. In a KFF survey of Puerto Ricans one year after the storm, a quarter said their lives were still somewhat or very disrupted and about a quarter said they or a household member had a new or worsened health condition since the storm.

- Worsening air quality also may negatively impact health in a variety of ways. Research suggests that climate change may contribute to increases in particulate matter and ground-level ozone—key components of smog and harmful air pollutants. The CDC notes that prolonged exposure to ozone can lead to worse lung function, an increase in cardiovascular- and respiratory-related hospital visits and admissions, and an increase in premature deaths. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development predicts that global annual health care costs associated with air pollution will increase from $21 billion in 2015 to $176 billion in 2060. Increases in wildfires due to changes in rain patterns and warmer summers may worsen air quality through the emission of particulate matter and other ozone-forming gases in smoke, which contribute to increased incidences of respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses. Moreover, longer and more intense pollen seasons stemming from longer warmer periods and increased carbon dioxide concentrations may negatively impact respiratory health, particularly for allergy and asthma sufferers. The CDC reports that medical costs associated with pollen exceed $3 billion each year and result in fewer productive work and school days.

Who is at Increased Risk for Negative Health Impacts Due to Climate and Climate Change?

While climate change poses health threats for everyone, people of color, low-income people, and other marginalized or high-need groups face disproportionate risks due to underlying inequities and structural racism and discrimination. The same factors that contribute to health inequities influence climate vulnerability— the degree to which people or communities are at risk of experiencing the negative impacts of climate change.

People of color face increased climate-related health risks compared to their White counterparts. As a result of historic and contemporary structural racism and discrimination, people of color are more likely to live in poverty; be exposed to environmental hazards; and have less access to health, economic, and social resources; making them more at risk for negative health impacts due to climate compared to their White counterparts. Last year, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found that racial and ethnic minorities were most likely to live in areas with the highest projected increases in morbidity and mortality due to climate related changes in temperatures and air pollution. They were more likely to lose labor hours and opportunities due to increases in high-temperature days. They were also the most likely to live in areas with projected land loss due to sea level change, as well as live in coastal areas with the highest projected increases in traffic delays due to high-tide flooding. For example:

- Historical policies such as redlining have led to residential segregation of Black people into urban neighborhoods that increase their exposure to extreme heat and poor air quality. Black people are 40% and 34% more likely than all other demographic groups to live in areas with the highest projected increases in extreme temperature-related deaths and the highest projected increases in childhood asthma diagnoses, respectively. Black people are also 41 to 60% more likely than non-Black people to live in areas with the highest projected increases in premature death due to exposure to harmful particulate matter. The disproportionate exposure to extreme heat and poor air quality increases their risk of premature mortality.

- Similarly, Hispanic people are 21% more likely to live in the hottest parts of cities, yet 30% of them do not have access to air-conditioning and are susceptible to the adverse outcomes associated with heat exposure. Additionally, they make up nearly half of agricultural workers and 28% of construction workers in the United States, among whom heat related illnesses are very common. Overall, Hispanic people are more than three times as likely to die from heat-related illnesses than non-Hispanic White people. Residential exposure to pesticides may also increase health risks. For example, in California, higher exposure to pesticides is associated with increased rates of testicular germ cell cancer, particularly among Latino people. Further, in the events of extreme weather, Hispanic people with limited English proficiency may be at increased risk due to lack of linguistically accessible information. For example, during a 2013 flash flood event an only Spanish-speaking family in Oklahoma missed warnings of severe flash floods and died while taking refuge from a tornado in a drainage ditch.

- Asian and Pacific Islander people are more likely to live in areas that are at a disproportionate risk of being excluded from adaptation measures that could mitigate the impacts of high-tide flooding-related traffic delays compared to non-Asian people and non-Pacific Islanders. U.S. colonial and military activity have also created legacies of environmental pollution in U.S. territories, including those in the Pacific Islands. In a recent study, researchers found that a majority of EPA violations on the islands occurred at or were associated with U.S. military sites. For example, Anderson Air Force Base in Guam which was placed on the National Priority List (NPL) due to the presence of hazardous materials is located above an aquifer that provides drinking water to at least 70% of the island’s residents. In American Samoa, soil and ground water analyzed from a local elementary school was found to be contaminated with fuel compounds, lead, and other heavy metals from when the U.S. Navy stored petroleum fuel on and used the site as a military installation during World War II. Exposure to fuel compounds, lead, and heavy metals can be harmful to health.

- Historic land dispossession of American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) Tribal lands has relegated many AIAN people to land that is disproportionately exposed to climate change risks, including extreme heat, wildfires, and reduced precipitation. As the average global temperature increases and sea levels rise, Tribal lands are being disproportionately eaten away by coastal erosion. One Inuit Eskimo village in Alaska, Shishmaref, had to relocate its entire population due to the impacts of climate change-related coastal erosion. AIAN people also have less access to potable water and, due to droughts, have more limited ability to grow their traditional heirloom crops. In addition, many AIAN Tribal lands are considered food deserts and lack access to healthy store-bought food making them reliant on less nutritious, convenience food store options.

Immigrants in the U.S. also face increased climate-related risks due to structural inequities. Immigrants are more likely than U.S. born people to work in environmentally hazardous professions and live in congregate housing with limited access to heating or cooling infrastructures, making them more susceptible to climate-related health risks. Noncitizen immigrants make up more than four in ten of agricultural workers in the United States. Data shows that between the years 1991 to 2006, agricultural workers engaged in crop production died at a 20 times higher rate from heat-related illnesses compared to all U.S. workers. Noncitizen immigrants also are more likely than citizens to be poor, which may contribute to increased challenges responding to and recovering from extreme weather events. For example, in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, immigrants were more likely than U.S.-born residents to report losses in employment and income. While immigrants were less likely to experience home damage, among those that did, they were less likely to have applied for government disaster assistance. Nearly half (48%) of immigrants with home damage said they were worried seeking help would draw attention to their or their families’ immigration statuses.

Low-income communities are likely to be disproportionately affected by climate change. People with low socioeconomic status are more likely to live in fragile housing, be exposed to environmental hazards, and have more limited ability to prepare for or recover from extreme climate events. Low-income households are more likely to have high energy burdens, a recent study found that 25% of low-income households could not afford to pay an energy bill in the past year, and nearly 13% were unable to pay an energy bill in the past month. This inability to pay their bills increases their likelihood of having their utilities disconnected, which would increase their exposure to extreme weather and resultant adverse health outcomes. In the event of extreme flooding and other weather, residents of federally assisted housing are put at an increased risk of exposure to toxic waste and runoff due to proximity to hazardous waste sites. A 2020 analysis found that 70% of the country’s most hazardous waste sites are located within one mile of U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)-assisted housing developments. Low-income communities are also more likely to be adversely impacted by natural disasters and other climate-related emergencies. In interviews with low-income survivors of Hurricane Katrina, KFF found that many survivors also reported suffering from emotional and mental trauma, barriers to accessing care resulting in serious and persistent gaps in care, unstable living conditions, and severe financial concerns. Similarly, a KFF survey of Puerto Ricans one year after Hurricane Maria found that those with lower incomes were more likely than residents with higher incomes to report housing-related challenges, including major damage or destruction of their home and unsafe housing conditions.

Older adults are more sensitive to climate change due to a variety of age-related reasons, including decreased thermoregulation, and a higher burden of chronic disease and disabilities. Given their age-related health changes, lower concentrations of air pollution and smaller temperature changes may result in adverse reactions. Analysis of fee-for-service Medicare data found that short-term exposure to air pollution was associated with an increase in annual hospital admissions and inpatient and post-acute care costs. Older people are also more likely to live alone and be socially isolated, putting them at increased risks of missing extreme weather warnings and potentially unable to respond to weather disasters. Further, in the last forty years, the number of older adults living in coastal communities has increased by 89%, which in combination with rising sea levels may put them at additional risk of being negatively affected by coastal flooding.

Why is a Focus on Climate Change and Health of Growing Importance?

In recent years, there has been an increase in the frequency and intensity of adverse climate-related events, with the potential to worsen health outcomes and exacerbate health inequities. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recently released its sixth report on climate change, noting that the risk to human health is increased with every fractional increase in global temperature. In June 2021, the western United States experienced record-breaking heat waves, increasing the risk of heat-related injuries, droughts, and wildfires. In addition to extreme heat, the past five years recorded some historical storm activity, with 2020 being the second time in history that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) exceeded the 21-name Atlantic list of storms. Researchers predict that the Earth will continue to experience an increase in its mean temperature, weather variability, and the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. A 2019 Government Accountability Office report found that the effects of climate change posed a threat to 60% of the hazardous waste sites known as Superfund sites in the country. In 2020, scientists reported that extreme coastal flooding would threaten more than 900 Superfund sites in the next 20 years. This could have detrimental impacts on nearby residents (primarily low-income and communities of color) by exposing them to toxic chemicals through flooding and runoff.

Changes in land use, increases in ambient temperature, and changes in weather patterns can impact the spread of infectious diseases. As temperature rise, scientists project changes in mosquito abundance and mosquito-borne disease spread, which could increase people’s exposure to dengue, zika, yellow fever, and other mosquito-borne diseases. In the past twenty years, the mosquitos that spread dengue fever in the United States increased by 8.2% in response to rapid temperature increases. Climate change-related temperature increases have also contributed to the expanded range of ticks, increasing the risk of contracting Lyme disease.

What are Current Federal Efforts to Address Climate Change and Health Equity?

While addressing climate change would require a massive and sustained effort, the Biden administration has identified addressing climate change as a priority and taken a range of actions focused on mitigating the impacts of climate change, including its impacts on health equity.

On January 27, 2021, President Biden announced an Executive order on tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, emphasizing the need for a government-wide approach to addressing the climate crisis, including centering climate change in all levels of policymaking. In response to Biden’s executive order, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) enacted its climate action plan, including the establishment of the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity (OCCHE) to address climate change and health equity. The climate action plan includes building more resilient and adaptive health programs, increasing the responsiveness to climate crises, and developing climate-resilient grant policies at HHS. In addition, OCCHE is tasked with creating an Interagency Working Group to Decrease Risk of Climate Change to Children, the Elderly, People with Disabilities, and the Vulnerable and a biennial Health Care System Readiness Advisory Council.

The executive order committed to delivering at least 40 percent of overall benefits from federal investments in climate and clean energy to disadvantaged communities. This includes addressing the impact Superfund sites have on communities, the launch of the Communities Local Energy Action Program (Communities LEAP), which helps communities that the fossil fuel industry has historically impacted to develop locally-driven energy plans to reduce local air pollution, increase energy resilience, lower both utility costs and energy burdens. The U.S. Department of Energy launched a $9 million effort to help 15 underserved and frontline communities better assess their energy storage as a means of achieving energy resilience and reducing energy insecurity.

In October 2021 Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) proposed a rule to protect workers from extreme heat exposure in indoor and outdoor settings and set up a National Emphasis Program (NEP) on heat inspections. The comment period for the proposed rule concluded on January 26, 2022. OSHA launched the NEP for Outdoor and Indoor Heat-Related Hazards on April 8, 2022. The NEP is an enforcement program that seeks to identify and eliminate or reduce worker exposures to occupational heat-related illnesses and injuries in workplaces where heat hazards are prevalent. It would include inspections prioritizing heat-related interventions and inspections of work activities on days when the heat index surpasses 80 degrees Fahrenheit. It is an expansion of the agency’s current heat-related illness prevention initiatives

The federal government has also taken several actions to protect disproportionately affected populations from exposure to toxic chemicals. The EPA revoked the usage of certain dangerous chemicals, including chlorpyrifos- a pesticide that negatively impacts farmworkers and children. There are also cross-agency efforts underway to reduce pollution burdens and exposures, including lead exposure and asthma disparities in children of color.

Last year, FEMA announced grants and initiatives dedicated to advancing climate change adaptation and promoting risk reduction and community resilience across the country. These include developing a FEMA National Risk Index to identify locations most at risk for 18 natural hazards, adopting climate resilience building standards, and dedicating funding to support communities at risk of being affected by climate-related extreme weather events and other natural disasters. For example: the Hazard Mitigation Assistance grant programs, Flood Mitigation Assistance grant program, Individuals and Households Program, and other programs. Hazard mitigation strategies play key roles in preventing or minimizing the impacts of natural disasters on communities by investing in and supporting climate resilient infrastructure. In collaboration with public health experts, these programs can also facilitate addressing health concerns caused and exacerbated by disasters, including reducing lapses in health care access, addressing physical and mental health challenges, spread of communicable disease, and others.