A View from the States: Key Medicaid Policy Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2019 and 2020

Eligibility and Premiums

| Key Section Findings |

| Since 2014, most major eligibility policy changes have been related to adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion. Maine and Virginia implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion in FY 2019, bringing the total number of states with the expansion in place as of July 2019 to 34. Three additional states have adopted the expansion but not yet implemented it, including Idaho which plans to implement the expansion in FY 2020. Utah expanded coverage for most adults to 100% FPL (without enhanced ACA matching funds) in April 2019. Other Medicaid eligibility expansions for FY 2019 and FY 2020 were narrow and targeted to a limited number of beneficiaries. In contrast, eligibility restrictions implemented in FY 2019 (by 7 states) or planned for implementation in FY 2020 (in 6 states) generally target broader Medicaid populations including expansion adults and parents/caretakers. All states implementing or planning eligibility policies that are counted as restrictions in FY 2019 or FY 2020 are doing so through Section 1115 waiver authority, whereas most states implementing or planning eligibility expansions are doing so through state plan authority.

What to watch:

Table 1 summarizes the nature of eligibility policy changes by state in FY 2019 and FY 2020. |

Changes to Eligibility Standards

Eligibility expansions

Aside from implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion in two states in FY 2019 and one additional state in FY 2020, most other eligibility expansions for FY 2019 and FY 2020 are narrow in scope. Overall, nine states implemented policy changes that expanded Medicaid eligibility in FY 2019, and 20 states plan to expand Medicaid eligibility in FY 2020. More states are pursuing eligibility expansions through State Plan Amendments (SPAs) compared to waivers in both FY 2019 and FY 2020 (Exhibit 1).

| Exhibit 1: Eligibility Expansions by Policy Authority | ||||

| FY 2019 | FY 2020 | |||

| State Plan Amendment | 7 States | CT, LA, MA, MD, ME, MO, VA | 13 States | CA, DC, ID, IA, LA, MA, MN, MO, ND, NJ, OK, WI, WV |

| Section 1115 Waiver | 2 States | IA, UT | 9 States | DE, HI, IL*, MO*, NJ*, NM*, RI, SC*, TN |

| *Indicates the Section 1115 Waiver has not yet been approved by CMS. | ||||

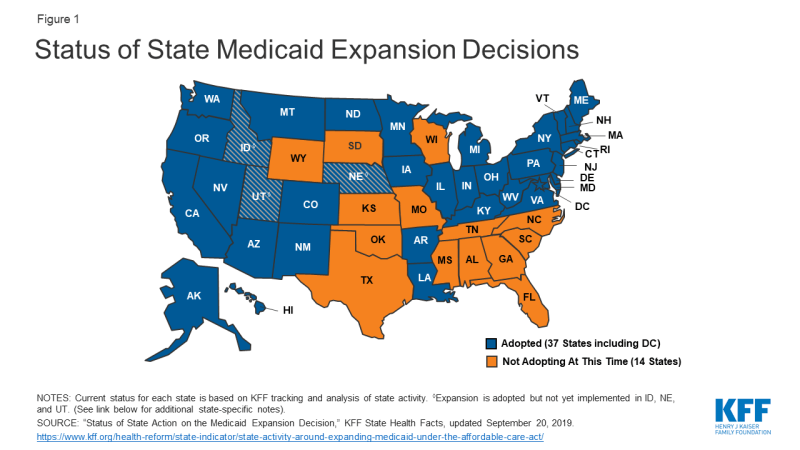

Two states (Maine and Virginia) implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion in FY 2019, bringing the total number of states that have implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion as of July 2019 to 34 (Figure 1). Expansion was implemented in Virginia and Maine in January 2019. Maine adopted the Medicaid expansion through a November 2017 ballot initiative. Due to delays by the former governor, however, implementation did not occur until the new governor signed an executive order in January 2019 directing the Department of Health and Human Services to begin expansion implementation and provide coverage to those eligible retroactive to July 2018. CMS approved the state’s plan retroactive to July 2, 2018.

Three states (Idaho, Nebraska and Utah) newly adopted the expansion through 2018 ballot initiatives, but implementation of the full expansion has been delayed in all three states. 1

- Utah voters approved a full ACA expansion to cover nearly all adults with income up to 138% of the FPL, however, the Utah legislature significantly changed and limited the coverage expansion that was adopted by the voters. The governor signed legislation in February 2019 that calls for multiple steps to implement an expansion of Medicaid coverage to adults in ways that differ from a full ACA expansion.2 As of October 2019, CMS had approved an amendment to Utah’s existing Section 1115 demonstration waiver to expand Medicaid to a capped number of adults with income up to 100% FPL beginning on April 1, 2019 at the state’s regular Medicaid matching rate, not the enhanced ACA matching rate. Additional waivers are pending/forthcoming per state law.3,4 If CMS does not approve the waivers by July 1, 2020 (the start of FY 2021), state legislation requires the state to adopt the full Medicaid expansion without restrictions as required by the ballot initiative.

- In Idaho, the governor signed a bill passed by the legislature in April 2019 that makes changes to the Medicaid expansion program approved by voters. The state submitted a Section 1332 waiver seeking permission to access the ACA enhanced match rate for the newly eligible population up to 100% FPL and for individuals between 100-138% FPL who choose to “opt-in” to Medicaid coverage. The state proposed that the default for the 100-138% FPL population would be qualified health plan (QHP) coverage in the Marketplace with advance premium tax credits. In August 2019, CMS rejected Idaho’s 1332 waiver request.5 The state will implement the Medicaid expansion to 138% FPL effective January 2020.

- Nebraska submitted an expansion SPA in April 2019 that delays implementation until October 1, 2020 (FY 2021) to allow time for the state to seek a Section 1115 waiver to implement expansion with program elements that differ from what is allowed under federal law.

In May 2019, the Montana governor signed legislation to continue the state’s Medicaid expansion program with significant changes until 2025. This action came after Montana residents voted down a measure on the November 2018 ballot that would have extended the Medicaid expansion beyond the June 30, 2019 sunset date and raised taxes on tobacco products to finance the expansion. Current legislation directs the state to seek federal waiver authority to make several changes to the existing expansion program, including adding a work requirement as a condition of eligibility and increasing the premiums required by many beneficiaries.

In a number of states, Medicaid expansion was still under debate for FY 2020 and beyond. In North Carolina, the governor vetoed the budget passed in late June 2019 primarily because it did not expand Medicaid. The budget stalemate continues as of October 2019. In September 2019, advocates in Missouri launched a campaign to put Medicaid expansion on the ballot in November 2020. To qualify for the ballot initiative, they must obtain at least 172,000 signatures. After legislation failed to pass last session in Kansas, in September 2019, the governor signed an executive order establishing a committee to study the Medicaid expansion experience in other states and to outline these findings for consideration during the 2020 legislative session.

Six states implemented more narrow eligibility expansions in FY 2019 and 19 states plan to implement more limited expansions in FY 2020. Some examples of these other expansions include the following:

- Restoring retroactive coverage. In FY 2019, Iowa reinstated retroactive eligibility for nursing facility residents. In FY 2020, Delaware and Oklahoma will restore retroactive eligibility for children and pregnant women. In FY 2020, Hawaii and New Mexico plan to reinstate retroactive eligibility for all groups.6 (The elimination of retroactive coverage requires a Section 1115 waiver.)

- Expanding coverage for pregnant and postpartum women. Three states (Illinois, Missouri, and South Carolina) are seeking waiver authority to extend coverage in FY 2020 for postpartum women beyond the current 60 days: Illinois plans to submit a Section 1115 waiver proposal to extend postpartum coverage to one year; Missouri’s proposal will specifically target women with a substance use disorder (SUD) diagnosis; South Carolina is seeking to extend coverage for pregnant women up to 199% FPL from 60 days postpartum to one-year postpartum. In addition, in FY 2020, North Dakota will increase the income limit for pregnant women from 152% FPL to 162% FPL, and West Virginia will increase the income limit for pregnant women from 150% FPL to 185% FPL.

- Covering children with disabilities/complex needs. Three states (Louisiana, Rhode Island, and Tennessee) are using either SPA or waiver authority to cover children with significant disabilities at home who would not qualify for Medicaid if the incomes and assets of their families were counted.

- Eliminating the 5-year waiting period for lawfully-residing immigrant children. In FY 2019, Louisiana eliminated the five-year waiting period for Medicaid eligibility for lawfully-residing immigrant children.

- Increasing the income limit for the parent/caretaker group and other limited groups.7 In FY 2020, if approved by CMS, South Carolina plans to increase the income limit for parent/caretakers from 67% FPL to 100% FPL. South Carolina’s pending waiver would also provide new coverage with an enrollment cap (that can be set at zero) for childless adults who are eligible due to homelessness, justice system involvement, or need for mental health or SUD treatment. The pending waiver includes a work requirement for non-exempt parent/caretakers and those in the new, capped enrollment groups.

Eligibility Restrictions

A number of states continue to pursue Section 1115 waivers which include policies that would result in eligibility restrictions in FY 2019 and FY 2020 (Exhibit 2). Policies that have or are likely to result in enrollment declines are counted as restrictions in this report. Seven states reported implementing restrictions in FY 2019 and six states reported restrictions already implemented or planned for implementation in FY 2020 (Exhibit 2 and Table 1).

Although not cited as eligibility standards changes, several states (not included in the counts below) noted a downward pressure on enrollment in FY 2019 or FY 2020 related to increased eligibility verifications, data matching, and other process-related issues.

| Exhibit 2: Eligibility Restrictions by Policy Authority | ||||

| FY 2019 | FY 2020 | |||

| State Plan Amendment | 0 States | 0 States | ||

| Section 1115 Waiver | 7 States | AR, FL, IN, KY, MA, NH, NM | 6 States | AZ, MI, MT*, UT, VA*, WI |

| *Indicates the Section 1115 Waiver has not yet been approved by CMS. | ||||

The most frequently reported eligibility restrictions implemented in FY 2019 or planned for FY 2020 are work or community engagement requirements. Work requirement waivers generally require beneficiaries to verify their participation in certain activities, such as employment, job search, or job training programs, for a certain number of hours per week or verify an exemption to receive or retain Medicaid coverage. Details about the specific number of hours, approved activities, exemptions, reporting process, and populations included (e.g., expansion adults and/or low-income parents) vary across states. Data show, however, that most Medicaid enrollees are already working or would qualify for exemptions from these requirements, yet many of these individuals would still need to navigate a reporting or exemption process to retain their Medicaid coverage.8,9,10 In this report, work requirement policies are counted based on the initial date of implementation rather than the date on which the first coverage terminations will occur.

| Exhibit 3: Work Requirement Waivers by Approval Status as of October 2019 | |

| Approved* | 6 States: AZ, IN, MI, OH, UT, WI |

| Pending+ | 9 States: AL, ID, MS, MT, OK, SC, SD, TN, VA |

| Vacated by Court^ | 3 States: AR, KY, NH |

| *AZ and OH plan to implement in FY 2021; +No non-expansion state pending work requirement waivers (AL, MS, OK, SC, SD, TN) were counted as “planned for implementation” in FY 2020 (see additional discussion below); ^AR, KY, and NH counted as eligibility restriction in FY 2019. | |

Six states currently have approved Section 1115 work requirement waivers (Exhibit 3). While Indiana began implementation of the work requirement in FY 2019 (in January 2019), no hours are required in the first 6 months. The phase-in of required hours began in months 7-9 with a requirement of 5 hours per week. Each December beneficiaries will be subject to a review of their community engagement hours for the prior 12-months. The first coverage losses are expected to take effect January 1, 2020 for beneficiaries who do not meet the required community engagement hours. (On September 23, 2019, a federal lawsuit was filed in the DC district court challenging the HHS Secretary’s approval of Indiana’s “Healthy Indiana Plan” waiver, including the approval of its work requirement (among other waiver provisions).) Michigan, Utah, and Wisconsin11 plan to implement work requirement waivers in FY 2020. Arizona and Ohio plan to implement work requirement waivers in FY 2021.

With the exception of Virginia, Montana, and Idaho, all other pending work requirement waivers are from non-expansion states. If approved, Virginia and Montana plan to implement work requirement waivers in FY 2020 and Idaho plans to implement in FY 2021.12 As of October 2019, CMS has not approved a work requirement waiver from a non-expansion state other than Wisconsin. The Wisconsin work requirement only applies to childless adults. Since there is no precedent for an approval of a work requirement waiver for parents and caretaker relatives in a non-expansion state and the timing of such an approval is unknown, this report does not count any non-expansion state pending work requirement waivers under “planned implementation” for FY 2020 (even though a few states indicated, depending on if/when approved, FY 2020 implementation may be possible).

As a result of litigation challenging work requirements, three states (Arkansas, Kentucky and New Hampshire) have had work requirement waivers set aside by the courts. On March 28, 2019, the DC federal district court set aside the HHS Secretary’s approval of Medicaid waivers with work and reporting requirements and other eligibility and enrollment restrictions in Kentucky and Arkansas.13 This was the second time the court ruled on Kentucky’s waiver, after finding that the Secretary’s initial approval was similarly flawed, and the first time the court considered Arkansas’s waiver. The court vacated both waivers – stopping work and reporting requirements as well as other waiver provisions. While Kentucky had not begun implementation, Arkansas’s waiver implementation began in June 2018 and resulted in over 18,000 people losing coverage.14 An appeal currently is underway in the DC Circuit.

On July 29, 2019, the DC federal district court set aside New Hampshire’s work requirement waiver. Implementation was stopped unless and until HHS issues a new approval that passes legal muster or prevails on appeal.15 Although the state began implementation in June 2019, no enrollees had lost coverage yet.

While several states moved to restore retroactive eligibility (described above), a few new states obtained waivers to eliminate or reduce retroactive coverage. In FY 2019, Florida eliminated retroactive coverage for non-pregnant adults. In FY 2020 (effective July 1, 2019), Arizona eliminated retroactive coverage for most newly eligible members excluding pregnant women and children. Although Maine received waiver approval (in December 2018) to eliminate retroactive eligibility, in January 2019 the incoming governor informed CMS that the state would not accept the terms of the approved waiver. Similarly, in New Mexico, a Section 1115 waiver amendment was approved in December 2018 that allowed the state to limit retroactive coverage to one month for most managed care members; however, under the new governor, the state submitted an amendment in June 2019 to reinstate the full 90-day retroactive coverage period. Finally, as a result of litigation challenging Section 1115 waivers, retroactive coverage restrictions were set aside/stopped in Arkansas, Kentucky, and New Hampshire.

Other examples of reported eligibility restrictions in FY 2019 or FY 2020 include:

- Conditioning eligibility on premium payment. In FY 2020, Virginia plans to implement (if their pending waiver is approved) premiums for non-exempt adults above 100% FPL. Coverage will be suspended for failure to pay premiums after a three-month grace period. In FY 2020, Wisconsin plans to implement premiums for childless adults from 50-100% FPL as a condition of eligibility, with disenrollment and a lock-out period for up to six months.

- Waiving reasonable promptness. In FY 2020, Virginia plans to implement (if their pending waiver is approved) a reasonable promptness waiver, delaying the start of coverage until after the first premium is paid for non-exempt enrollees above 100% FPL.

- Conditioning eligibility on completion of a health risk assessment. In FY 2020, Wisconsin will condition eligibility for childless adults on the completion of a health risk assessment.

Many states implementing Section 1115 waivers that include eligibility conditions (e.g., work requirements, coverage lockouts, and premium requirements) indicated that these policies impact administrative processes and expenses. Specific examples noted include:

- Information system costs – data matches and interfaces with other programs, creation of enrollee reporting portals, and development of automated participant notices16

- Staffing costs and contract changes – call center staff, staff or contractors for outreach and education, staff to invoice and track premiums

- MCO contract changes – requiring plans to verify exemptions, manage premium collections and reductions, etc.

Births Financed by Medicaid

Medicaid is a key source of financing of births for low- and modest-income families. Women who would not otherwise be eligible can qualify for Medicaid coverage for pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum care due to higher income eligibility thresholds for pregnant women.17 Medicaid directors were asked to provide the most recent available data on the share of all births in their states that were financed by Medicaid. About three-quarters of the 50 reporting states were able to provide data for calendar year or fiscal year 2017 or 2018. The rest of the states provided data from 2013-2016 or 2019. The median share of births financed by Medicaid in the 50 reporting states was 46%. Six states (Arkansas, Louisiana,18 Mississippi, Nevada, New Mexico, and South Carolina) reported that Medicaid pays for 60% or more of all births in their state, while four states reported that Medicaid finances less than 30% of all births (New Hampshire, North Dakota, Utah, and Vermont).

Premiums

The Medicaid statute generally does not allow states to charge premiums to most Medicaid beneficiaries. Historically, premiums were limited to special higher income categories of beneficiaries such as expanded Medicaid for working people with disabilities. However, some states have obtained waiver authority to charge higher premiums and/or copayments than otherwise allowed, especially for the Medicaid expansion population.

Four states (Iowa, Indiana, Maine, and Wisconsin) reported implementation of new premium programs or changes to existing premiums in FY 2019. In FY 2019, Indiana implemented a tobacco premium surcharge for expansion adults and low-income parent/caretakers, increasing premiums by 50% for tobacco users beginning in their second year of enrollment, as part of its Healthy Indiana Plan (“HIP”) waiver. Maine implemented premium increases in its long-standing Section 1115 waiver serving persons with HIV/AIDS. Those subject to premium amounts will see premiums increase 5% annually over the ten-year demonstration period. Effective July 1, 2018, Iowa added a new $3 per month premium for Dental Wellness Program (DWP) members that do not complete healthy behaviors. Effective January 1, 2019, Wisconsin ended premiums for parents and caretaker relatives receiving Medicaid under the Transitional Medical Assistance component of the program. New Mexico had obtained approval under a Section 1115 waiver to implement premiums for expansion adults above 100% FPL starting in 2019; however, the state, under a new governor, is amending the waiver to remove this authority and does not intend to implement premiums.

Four states (Idaho, Montana, Virginia, and Wisconsin) reported planned implementation of new premium programs or changes to existing premiums in FY 2020. Montana and Virginia have implemented or plan to implement new premiums or premium changes for Medicaid expansion adults. Montana’s pending waiver request proposes to gradually increase premiums for each year a member is enrolled in the expansion (from 2% of income for the first two years up to 4% at the rate of 0.5% per year) for expansion adults 50-138% FPL. Virginia’s pending waiver request would add premiums for expansion adults above 100% FPL. In FY 2020, Wisconsin plans to implement premiums for childless adults which will vary based on completion of a health risk assessment and healthy behaviors. Finally, Idaho is planning to implement premiums for children in its Serious Emotional Disturbance (SED) Youth Empowerment Services (“YES”) Section 1915(i) program in FY 2020.

Coverage Initiatives for the Criminal Justice Population

The Medicaid expansion provided a new coverage option for many individuals involved with the criminal justice system, especially childless adults who were not previously eligible in most states. While Medicaid cannot pay for services other than inpatient hospitalization during incarceration, most states are seeking ways to promptly provide coverage and health care services to individuals upon release. Maintenance of medications and access to behavioral health services can be important factors in mitigating recidivism rates.19

Most states reported policies already in place as of FY 2019 to suspend Medicaid eligibility for incarcerated individuals in both prisons and jails (Exhibit 4). When Medicaid eligibility is suspended (instead of terminated) when an enrollee becomes incarcerated, a simple change in status can allow for prompt reinstatement of eligibility upon release from incarceration. Six states plan to implement suspension policies for prisons and jails in FY 2020. Alabama already suspends Medicaid eligibility for individuals incarcerated in jails but plans to implement the suspension policy for prisons in FY 2020.

| Exhibit 4: Suspension of Medicaid Eligibility for Incarcerated Individuals | ||

| Prisons | Jails | |

| In place as of FY 2019 | 43 states | 42 states |

| Plan to implement in FY 2020 | AL, ID, MO, NV, OK, UT, WI | ID, MO, NV, OK, UT, WI |

| No plans to implement in FY 2019 or FY 2020 | KS | IL, KS, NC |

States were also asked if Medicaid eligibility agencies have an electronic, automated data exchange process with jails and/or prisons to facilitate suspension and reinstatement of eligibility for individuals moving into and out of incarceration. About half of states (23 states) indicated such processes were in place in FY 2019. Nine additional states indicated plans to implement an electronic, automated data exchange process in FY 2020. Seventeen states indicated there are no current plans to implement such a process.20

| SUPPORT Act: Foster Care Eligibility |

| As of October 1, 2019, The Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (SUPPORT) Act prohibits states from terminating Medicaid eligibility for individuals under age 21 or former foster care youth up to age 26 while they are incarcerated and also requires states to redetermine eligibility for these populations prior to release without requiring a new application and to restore coverage upon release.21 States were asked to describe any challenges or issues related to coming into compliance with these requirements. About half of states indicated that they are not facing challenges related to complying with this requirement. In contrast, other states indicated that this policy presents challenges or requires significant additional steps including new process development, system changes, development of automated data exchanges, interagency communication and coordination, changes to state laws, and need for additional federal guidance. |

Table 1: Changes to Eligibility Standards in all 50 States and DC, FY 2019 and FY 2020

|

Eligibility Standard Changes |

||||||

|

States |

FY 2019 |

FY 2020 |

||||

|

(+) |

(-) |

(#) |

(+) |

(-) |

(#) |

|

|

Alabama |

||||||

|

Alaska |

||||||

|

Arizona |

X |

|||||

|

Arkansas |

X |

* |

||||

|

California |

X |

|||||

|

Colorado |

||||||

|

Connecticut |

X |

|||||

|

Delaware |

X |

|||||

|

DC |

X |

X |

||||

|

Florida |

X |

|||||

|

Georgia |

||||||

|

Hawaii |

X |

|||||

|

Idaho |

X |

|||||

|

Illinois |

X |

|||||

|

Indiana |

X |

X |

||||

|

Iowa |

X |

X |

||||

|

Kansas |

||||||

|

Kentucky |

X |

* |

||||

|

Louisiana |

X |

X |

||||

|

Maine |

X |

|||||

|

Maryland |

X |

|||||

|

Massachusetts |

X |

X |

X |

|||

|

Michigan |

|

X |

||||

|

Minnesota |

X |

|||||

|

Mississippi |

||||||

|

Missouri |

X |

X |

||||

|

Montana |

X |

|||||

|

Nebraska |

||||||

|

Nevada |

||||||

|

New Hampshire |

X |

* |

||||

|

New Jersey |

X |

|||||

|

New Mexico |

X |

X |

||||

|

New York |

||||||

|

North Carolina |

||||||

|

North Dakota |

X |

|||||

|

Ohio |

||||||

|

Oklahoma |

X |

|||||

|

Oregon |

||||||

|

Pennsylvania |

||||||

|

Rhode Island |

X |

|||||

|

South Carolina |

X |

|||||

|

South Dakota |

||||||

|

Tennessee |

X |

|||||

|

Texas |

||||||

|

Utah |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Vermont |

||||||

|

Virginia |

X |

X |

||||

|

Washington |

||||||

|

West Virginia |

X |

|||||

|

Wisconsin** |

X |

X |

||||

|

Wyoming |

||||||

|

Totals |

9 |

7 |

1 |

20 |

6 |

3 |

|

NOTES: From the beneficiary’s perspective, eligibility expansions or policies likely to increase Medicaid enrollment are denoted with (+), eligibility restrictions or policies likely to decrease enrollment are denoted with (-), and neutral changes are denoted with (#). This table captures eligibility changes that states have implemented or plan to implement in FY 2019 or FY 2020, including changes that are part of approved and pending Section 1115 waivers. No non-expansion state pending work requirement waivers (AL, MS, OK, SC, SD, TN) were counted as “planned for implementation” in FY 2020. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2019. |

||||||