The Build Back Better Act, H.R. 5376, (BBBA), adopted by the House of Representatives on November 19, 2021 with the support of President Biden, includes a broad package of health, social, climate change and revenue provisions. The total package includes $1.7 trillion in spending, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which also projects that three of the health provisions would reduce the number of uninsured by 3.4 million people. This brief summarizes the version that passed the House, which may be modified as it moves through the Senate.

Here, we walk through 11 of the major health coverage and financing provisions of the Build Back Better Act, with discussion of the potential implications for people and the federal budget. We summarize provisions relating to the following areas and provide data on the people most directly affected by each provision and the potential costs or savings to the federal government.

- ACA Marketplace Subsidies

- New Medicare Hearing Benefit

- Lowering Prescription Drug Prices and Spending

- Medicare Part D Benefit Redesign

- Medicaid Coverage Gap

- Maternal Care and Postpartum Coverage

- Other Medicaid / Children’s Health Insurance Changes CHIP Changes

- Other Medicaid Financing and Benefit Changes

- Medicaid Home and Community Based Services and the Direct Care Workforce

- Paid Family and Medical Leave

- Consumer Assistance, Enrollment Assistance, and Outreach

A recent KFF poll found broad support for many of these provisions, though it did not probe on the costs or trade-offs associated with them. The poll also found that the vast majority of the public supports allowing the federal government to negotiate drug prices, after hearing arguments made by proponents and opponents.

Major Provisions of the Build Back Better Act and their Potential Costs and Impact

1. ACA Marketplace Subsidies

Background

Under the Affordable Care Act, people purchasing Marketplace coverage could only qualify for subsidies if they met other eligibility requirements and had incomes between one and four times the federal poverty level. People eligible for subsidies would have to contribute a sliding-scale percentage of their income toward a benchmark premium, ranging from 2.07% to 9.83%. Once income passed 400% FPL, subsidies stopped and many individuals and families were unable to afford coverage.

In 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) temporarily expanded eligibility for subsidies by removing the upper income threshold. It also temporarily increased the dollar value of premium subsidies across the board, meaning nearly everyone on the Marketplace paid lower premiums, and the lowest income people pay zero premium for coverage with very low deductibles. The ARPA also made people who received unemployment insurance (UI) benefits during 2021 eligible for zero-premium, low-deductible plans.

However, the ARPA provisions removing the upper income threshold and increasing tax credit amounts are only in effect for 2021 and 2022. The unemployment provision is only in effect for 2021.

Provision Description

Section 137301 of The Build Back Better Act would extend the ARPA subsidy changes that eliminate the income eligibility cap and increase the amount of APTC for individuals across the board through the end of 2025.

Additionally, Section 30605 of The Build Back Better Act would extend the special Marketplace subsidy rule for individuals receiving UI benefits for an additional 4 years, through the end of 2025.

Section 137303 of the Act would, for purposes of determining eligibility for premium tax credits, disregard any lump sum Social Security benefit payments in a year. This provision would be permanent and effective starting in the 2022 tax year. Starting in 2026, people would have the option to have the lump sum benefit included in their income for purposes of determining tax credit eligibility.

Finally, Section 137302 modifies the affordability test for employer-sponsored health coverage. The ACA makes people ineligible for marketplace subsidies if they have an offer of affordable coverage from an employer, currently defined as requiring an employee contribution of no more than 9.61% of household income in 2022. The Build Back Better Act would reduce this affordability threshold to 8.5% of income, bringing it in line with the maximum contribution required to enroll in the benchmark marketplace plan. This provision would take effect for tax years starting in 2022 through 2025. Thereafter the affordability threshold would be set at 9.5% of household income with no indexing.

People Affected

CBO projects that the enhanced tax credits in Section 137301 would reduce the number of uninsured by 1.2 million people. As of August 2021, 12.2 million people were actively enrolled in Marketplace plans – an 8% increase from 11.2 million people enrollees as of the close of Open Enrollment for the 2021 plan year. HealthCare.gov and all state Marketplaces reopened for a special enrollment period of at least 6 months in 2021, enrolling 2.8 million people (not all of whom were necessarily previously uninsured). Of these, 44% selected plans with monthly premiums of $10 or less.

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) reports that ARPA reduced Marketplace premiums for the 8 million existing Healthcare.gov enrollees by $67 per month, on average. If the ARPA subsidies are allowed to expire, these enrollees will likely see their premium payments double.

HHS also reports that between July 1 and August 15, more than 280,000 individuals received enhanced subsidies due to the ARPA UI provisions. Individuals eligible for these UI benefits can continue to enroll in 2021 coverage through the end of this year.

The ARPA changes made people with income at or below 150% FPL eligible for zero-premium silver plans with comprehensive cost sharing subsidies. 40% of new consumers who signed up during the SEP are in a plan that covers 94% of expected costs (with average deductibles below $200). As a result of the ARPA, HHS reports the median deductible for new consumers selecting plan during the COVID-SEP decreased by more than 90% (from $750 in 2020 to $50 in 2021).

With the ARPA and ACA subsidies, as well as Medicaid in states that expanded the program, we estimate that at least 46% of non-elderly uninsured people in the U.S. are eligible for free or nearly-free health plans, often with low or no deductibles.

Budgetary Impact

CBO estimates that extension of the ARPA marketplace subsidy improvements through 2025 (Section 13701) will cost $73.9 billion over the ten-year budget window, with “cost” reflecting both direct spending and on-budget revenue losses. This total also includes the cost of modifying the affordability threshold for employer-sponsored coverage (Section 13602)

CBO further estimates the cost of extending the enhanced marketplace subsidies for people receiving unemployment benefits (Section 13705) will be $1.8 billion over the ten-year budget window.

The cost of disregarding lump sum Social Security benefits payments for purposes of determining premium tax credit eligibility (Section 13703) is $416 million over the ten-year budget window.

(Back to top)

2. New Medicare Hearing Benefit

background

Medicare currently does not cover hearing services, except under limited circumstances, such as cochlear implantation when beneficiaries meet certain eligibility criteria. Hearing services are typically offered as an extra benefit by Medicare Advantage plans, and in 2021, 97% of Medicare Advantage enrollees in individual plans, or 17.1 million people, are offered some hearing benefits, but according to our analysis, the extent of that coverage and the value of these benefits varies. Some beneficiaries in traditional Medicare may have private coverage or coverage through Medicaid for these services, but many do not.

Provision Description

Section 30901 of the Build Back Better Act would add coverage of hearing services to Medicare Part B, beginning in 2023. Coverage for hearing care would include hearing rehabilitation and treatment services by qualified audiologists, and hearing aids. Hearing aids would be available once per ear, every 5 years, to individuals diagnosed with moderately severe, severe, or profound hearing loss. Hearing services would be subject to the Medicare Part B deductible and 20% coinsurance. Hearing aids would be covered similar to other Medicare prosthetic devices and would also be subject to the Part B deductible and 20% coinsurance. For people in traditional Medicare who have other sources of coverage such as Medigap or Medicaid, their cost sharing for these services might be covered. Payment for hearing aids would only be on an assignment-related basis. As with other Medicare-covered benefits, Medicare Advantage plans would be required to cover these hearing benefits.

Effective Date: The Medicare hearing benefit provision would take effect in 2023.

People Affected

Adding coverage of hearing services, including hearing aids, to Medicare would help beneficiaries with hearing loss who might otherwise go without treatment by an audiologist or hearing aids, particularly those who cannot afford the cost of hearing aids. It would also lower out-of-pocket costs for some beneficiaries who would otherwise pay the full cost of their hearing aids without the benefit. Among beneficiaries who used hearing services in 2018, average out-of-pocket spending according to our analysis was $914, although many hearing aids are considerably more expensive than the average.

While the majority of enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans have access to a hearing benefit, a new defined Medicare Part B benefit could also lead to enhanced and more affordable hearing benefits for Medicare Advantage enrollees. Because costs are often a barrier to care, adding this benefit to Medicare could increase use of these services, and contribute to better health outcomes.

BUDGETARY IMPACT

CBO estimates that the new Medicare Part B hearing benefit would increase federal spending by $36.7 billion over 10 years (2022-2031).

(Back to top)

3. Lowering Prescription Drug Prices and Spending

background

Currently, under the Medicare Part D program, which covers retail prescription drugs, Medicare contracts with private plan sponsors to provide a prescription drug benefit. The law that established the Part D benefit includes a provision known as the “noninterference” clause, which stipulates that the HHS Secretary “may not interfere with the negotiations between drug manufacturers and pharmacies and PDP [prescription drug plan] sponsors, and may not require a particular formulary or institute a price structure for the reimbursement of covered part D drugs.” For drugs administered by physicians that are covered under Medicare Part B, Medicare reimburses providers 106% of the Average Sales Price (ASP), which is the average price to all non-federal purchasers in the U.S, inclusive of rebates, A recent KFF Tracking Poll finds large majorities support allowing the federal government to negotiate and this support holds steady even after the public is provided the arguments being presented by parties on both sides of the legislative debate (83% total, 95% of Democrats, 82% of independents, and 71% of Republicans).

In addition to the inability to negotiate drug prices under Part D, Medicare lacks the ability to limit annual price increases for drugs covered under Part B (which includes those administered by physicians) and Part D. In contrast, Medicaid has an inflationary rebate in place. Year-to-year drug price increases exceeding inflation are not uncommon and affect people with both Medicare and private insurance. Our analysis shows that half of all covered Part D drugs had list price increases that exceeded the rate of inflation between 2018 and 2019.

provision description

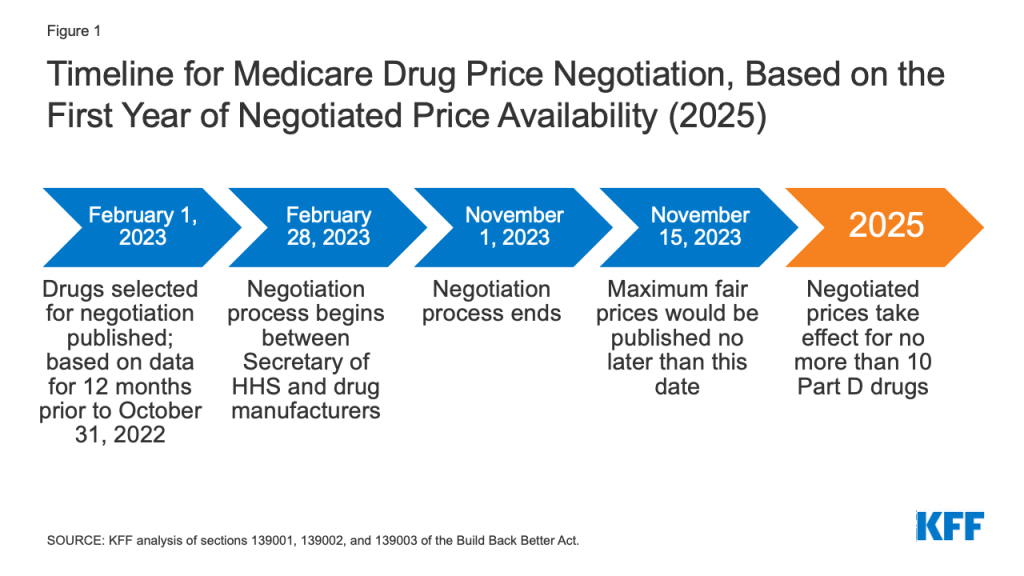

Drug Price Negotiations. Sections 139001, 139002, and 139003 of the Build Back Better Act would amend the non-interference clause by adding an exception that would allow the federal government to negotiate prices with drug companies for a small number of high-cost drugs lacking generic or biosimilar competitors covered under Medicare Part B and Part D. The negotiation process would apply to no more than 10 (in 2025), 15 (in 2026 and 2027), and 20 (in 2028 and later years) single-source brand-name drugs lacking generic or biosimilar competitors, selected from among the 50 drugs with the highest total Medicare Part D spending and the 50 drugs with the highest total Medicare Part B spending (for 2027 and later years). The negotiation process would also apply to all insulin products.

The legislation exempts from negotiation drugs that are less than 9 years (for small-molecule drugs) or 13 years (for biological products, based on the Manager’s Amendment) from their FDA-approval or licensure date. The legislation also exempts “small biotech drugs” from negotiation until 2028, defined as those which account for 1% or less of Part D or Part B spending and account for 80% or more of spending under each part on that manufacturer’s drugs.

The proposal establishes an upper limit for the negotiated price (the “maximum fair price”) equal to a percentage of the non-federal average manufacturer price: 75% for small-molecule drugs more than 9 years but less than 12 years beyond approval; 65% for drugs between 12 and 16 years beyond approval or licensure; and 40% for drugs more than 16 years beyond approval or licensure. Part D drugs with prices negotiated under this proposal would be required to be covered by all Part D plans. Medicare’s payment to providers for Part B drugs with prices negotiated under this proposal would be 106% of the maximum fair price (rather than 106% of the average sales price under current law).

An excise tax would be levied on drug companies that do not comply with the negotiation process, and civil monetary penalties on companies that do not offer the agreed-upon negotiated price to eligible purchasers.

Effective Date: The negotiated prices for the first set of selected drugs (covered under Part D) would take effect in 2025. For drugs covered under Part B, negotiated prices would first take effect in 2027.

Inflation Rebates. Sections 139101 and 139102 of the Build Back Better Act would require drug manufacturers to pay a rebate to the federal government if their prices for single-source drugs and biologicals covered under Medicare Part B and nearly all covered drugs under Part D increase faster than the rate of inflation (CPI-U). Under these provisions, price changes would be measured based on the average sales price (for Part B drugs) or the average manufacturer price (for Part D drugs). For price increase higher than inflation, manufacturers would be required to pay the difference in the form of a rebate to Medicare. The rebate amount is equal to the total number of units multiplied by the amount if any by which the manufacturer price exceeds the inflation-adjusted payment amount, including all units sold outside of Medicaid and therefore applying not only to use by Medicare beneficiaries but by privately insured individuals as well. Rebate dollars would be deposited in the Medicare Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) trust fund.

Manufacturers that do not pay the requisite rebate amount would be required to pay a penalty equal to at least 125% of the original rebate amount. The base year for measuring price changes is 2021.

Effective Date: These provisions would take effect in 2023.

Limits on Cost Sharing for Insulin Products. Sections 27001, 30604, 137308, and 139401 would require insurers, including Medicare Part D plans and private group or individual health plans, to charge no more than $35 for insulin products. Part D plans would be required to charge no more than $35 for whichever insulin products they cover for 2023 and 2024 and all insulin products beginning in 2025. Coverage of all insulin products would be required beginning in 2025 because the drug negotiation provision (described earlier) would require all Part D plans to cover all drugs that are selected for price negotiation, and all insulin products are subject to negotiation under that provision. Private group or individual plans do not have to cover all insulin products, just one of each dosage form (vial, pen) and insulin type (rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting, and long-acting) for no more than $35.

Effective Date: These provisions would take effect in 2023.

Vaccines. Section 139402 would require that adult vaccines covered under Medicare Part D that are recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), such as for shingles, be covered at no cost. This would be consistent with coverage of vaccines under Medicare Part B, such as the flu and COVID-19 vaccines.

Effective Date: This provision would take effect in 2024.

Repealing the Trump Administration’s Drug Rebate Rule. Section 139301 would prohibit implementation of the November 2020 final rule issued by the Trump Administration that would have eliminated rebates negotiated between drug manufacturers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) or health plan sponsors in Medicare Part D by removing the safe harbor protection currently extended to these rebate arrangements under the federal anti-kickback statute. This rule was slated to take effect on January 1, 2022, but the Biden Administration delayed implementation to 2023 and the infrastructure legislation passed by the House and Senate includes a further delay to 2026.

Effective Date: This provision would take effect in 2026.

People affected

The number of Medicare beneficiaries and privately insured individuals who would see lower out-of-pocket drug costs in any given year under these provisions would depend on how many and which drugs were subject to the negotiation process, and how many and which drugs had lower price increases, and the magnitude of price reductions relative to current prices under each provision.

Neither CBO nor the Biden Administration have published estimates of beneficiary premium and out-of-pocket budget effects associated with the provision to allow the HHS Secretary to negotiate drug prices. An earlier version of the negotiations proposal in H.R.3 that passed the House of Representatives in 2019 would have lowered cost sharing for Part D enrollees by $102.6 billion in the aggregate (2020-2029) and Part D premiums for Medicare beneficiaries by $14.3 billion. Based on our analysis of the H.R. 3 version of this provision, the negotiations provision in H.R. 3 would have reduced Medicare Part D premiums for Medicare beneficiaries by an estimated 9% of the Part D base beneficiary premium in 2023 and by as much as 15% in 2029. However, the effects on beneficiary premiums and cost sharing under the drug negotiation provision in the BBBA are expected to be more modest than the effects of H.R. 3 due to the smaller number of drugs eligible for negotiation and a different method of calculating the maximum fair price.

While it is expected that some people would face lower cost sharing under these provisions, it is also possible that drug manufacturers could respond to the inflation rebate by increasing launch prices for new drugs. In this case, some individuals could face higher out-of-pocket costs for new drugs that come to market, with potential spillover effects on total costs incurred by payers as well.

In terms of insulin costs, a $35 cap on monthly cost sharing for insulin products could lower out-of-pocket costs for many insulin users with private insurance and those in Medicare Part D without low-income subsidies. While formulary coverage and tier placement of insulin products vary across Medicare Part D plans, our analysis shows that in 2019, a large number of Part D plans placed insulin products on Tier 3, the preferred drug tier, which typically had a $47 copayment per prescription during the initial coverage phase. However, once enrollees reach the coverage gap phase, they face a 25% coinsurance rate, which equates to $100 or more per prescription in out-of-pocket costs for many insulin therapies, unless they qualify for low-income subsidies. Paying a flat $35 copayment rather than 25% coinsurance could reduce out-of-pocket costs for many people with diabetes who use insulin products.

In terms of vaccines, providing for coverage of adult vaccines under Medicare Part D at no cost could help with vaccine uptake among older adults and would lower out-of-pocket costs for those who need Part D-covered vaccines. Our analysis shows that in 2018, Part D enrollees without low-income subsidies paid an average of $57 out-of-pocket for each dose of the shingles shot, which is generally free to most other people with private coverage.

budgetary impact

Drug Price Negotiations. CBO estimates $78.8 billion in Medicare savings over 10 years (2022-2031) from the drug negotiation provisions.

Inflation Rebates. CBO estimates a net federal deficit reduction of $83.6 billion over 10 years (2022-2031) from the drug inflation rebate provisions in the BBBA. This includes net savings of $49.4 billion ($61.8 billion in savings to Medicare and $7.7 billion in savings for other federal programs, such as DoD, FEHB, and subsides for ACA Marketplace coverage, offset by $20.1 billion in additional Medicaid spending) and higher federal revenues of $34.2 billion.

Limits on Cost Sharing for Insulin Products. CBO estimates additional federal spending of $1.4 billion ($0.9 billion for Medicare and $0.5 billion in other federal spending) and a reduction in federal revenues of $4.6 billion over 10 years associated with the insulin cost-sharing limits in the BBBA.

Vaccines. CBO estimates that this provision would increase federal spending by $3.3 billion over 10 years (2022-2031).

Repealing the Trump Administration’s Drug Rebate Rule. Because the rebate rule was finalized (although not implemented), its cost has been incorporated in CBO’s baseline for federal spending. Therefore, repealing the rebate rule is expected to generate savings. CBO estimates savings of $142.6 billion from the repeal of the Trump Administration’s rebate rule between 2026 (when the BBBA provision takes effect) and 2031. In addition, CBO estimated savings of $50.8 billion between 2023 and 2026 for the three-year delay of this rule included in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

(Back to top)

4. Medicare Part D Benefit Redesign

background

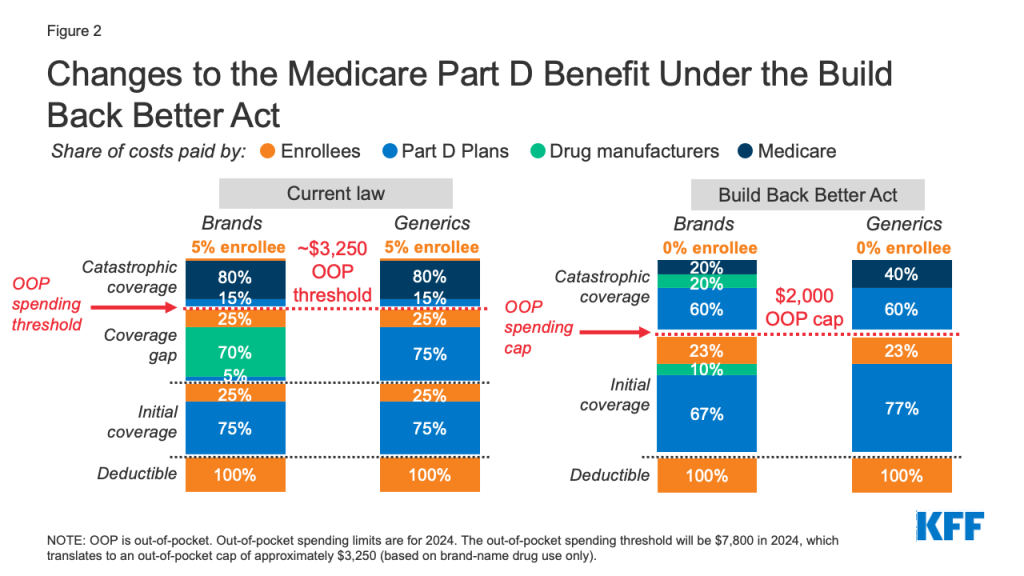

Medicare Part D currently provides catastrophic coverage for high out-of-pocket drug costs, but there is no limit on the total amount that beneficiaries pay out-of-pocket each year. Medicare Part D enrollees with drug costs high enough to exceed the catastrophic coverage threshold are required to pay 5% of their total drug costs unless they qualify for Part D Low-Income Subsidies (LIS). Medicare pays 80% of total costs above the catastrophic threshold and plans pay 15%. Medicare’s reinsurance payments to Part D plans now account for close to half of total Part D spending (45%), up from 14% in 2006.

Under the current structure of Part D, there are multiple phases, including a deductible, an initial coverage phase, a coverage gap phase, and the catastrophic phase. When enrollees reach the coverage gap benefit phase, they pay 25% of drug costs for both brand-name and generic drugs; plan sponsors pay 5% for brands and 75% for generics; and drug manufacturers provide a 70% price discount on brands (there is no discount on generics). Under the current benefit design, beneficiaries can face different cost sharing amounts for the same medication depending on which phase of the benefit they are in, and can face significant out-of-pocket costs for high-priced drugs because of coinsurance requirements and no hard out-of-pocket cap.

provision description

Sections 139201 and 139202 of the Build Back Better Act amend the design of the Part D benefit by adding a hard cap on out-of-pocket spending set at $2,000 in 2024, increasing each year based on the rate of increase in per capita Part D costs. It also lowers beneficiaries’ share of total drug costs below the spending cap from 25% to 23%. It also lowers Medicare’s share of total costs above the spending cap (“reinsurance”) from 80% to 20% for brand-name drugs and to 40% for generic drugs; increases plans’ share of costs from 15% to 60% for both brands and generics; and adds a 20% manufacturer price discount on brand-name drugs. Manufacturers would also be required to provide a 10% discount on brand-name drugs in the initial coverage phase (below the annual out-of-pocket spending threshold), instead of a 70% price discount.

The legislation also increases Medicare’s premium subsidy for the cost of standard drug coverage to 76.5% (from 74.5% under current law) and reduces the beneficiary’s share of the cost to 23.5% (from 25.5%). The legislation also allows beneficiaries the option of smoothing out their out-of-pocket costs over the year rather than face high out-of-pocket costs in any given month.

Effective Date: The Part D redesign and premium subsidy changes would take effect in 2024. The provision to smooth out-of-pocket costs would take effect in 2025.

people affected

Medicare beneficiaries in Part D plans with relatively high out-of-pocket drug costs are likely to see substantial out-of-pocket cost savings from this provision. While most Part D enrollees have not had out-of-pocket costs high enough to exceed the catastrophic coverage threshold in a single year, the likelihood of a Medicare beneficiary incurring drug costs above the catastrophic threshold increases over a longer time span.

Our analysis shows that in 2019, nearly 1.5 million Medicare Part D enrollees had out-of-pocket spending above the catastrophic coverage threshold. Looking over a five-year period (2015-2019), the number of Part D enrollees with out-of-pocket spending above the catastrophic threshold in at least one year increases to 2.7 million, and over a 10-year period (2010-2019), the number of enrollees increases to 3.6 million.

Based on our analysis, 1.2 million Part D enrollees in 2019 incurred annual out-of-pocket costs for their medications above $2,000 in 2019, averaging $3,216 per person. Based on their average out-of-pocket spending, these enrollees would have saved $1,216, or 38% of their annual costs, on average, if a $2,000 cap had been in place in 2019. Part D enrollees with higher-than-average out-of-pocket costs could save substantial amounts with a $2,000 out-of-pocket spending cap. For example, the top 10% of beneficiaries (122,000 enrollees) with average out-of-pocket costs for their medications above $2,000 in 2019 – who spent at least $5,348 – would have saved $3,348 (63%) in out-of-pocket costs with a $2,000 cap.

budgetary impact

CBO estimates the benefit redesign and smoothing provisions of the BBBA would reduce federal spending by $1.5 billion over 10 years (2022-2031), which consists of $1.6 billion in lower spending associated with Part D benefit redesign and $0.1 billion in higher spending associated with the provision to smooth out-of-pocket costs.

(Back to top)

5. Medicaid Coverage Gap

background

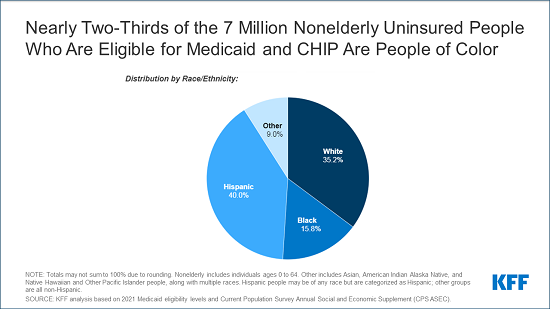

There are currently 12 states that have not adopted the ACA provision to expand Medicaid to adults with incomes through 138% of poverty. The result is a coverage gap for individuals whose below-poverty-level income is too high to qualify for Medicaid in their state, but too low to be eligible for premium subsidies in the ACA Marketplace.

provision description

Section 137304 of the Build Back Better Act would allow people living in states that have not expanded Medicaid to purchase subsidized coverage on the ACA Marketplace for 2022 through 2025. The federal government would fully subsidize the premium for a benchmark plan. People would also be eligible for cost sharing subsidies that would reduce their out-of-pocket costs to 1% of overall covered health expenses on average.

Section 30608 includes adjustments to uncompensated care (UCC) pools and disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments for non-expansion states. These states would not be able draw down federal matching funds for UCC amounts for individuals who could otherwise qualify for Medicaid expansion, and their DSH allotments would be reduced by 12.5% starting in 2023.

Section 30609 would increase the federal match rate for states that have adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion from 90% to 93% from 2023 through 2025, designed to discourage states from dropping current expansion coverage.

people affected

We estimate that 2.2 million uninsured people with incomes under poverty fall in the “coverage gap”. Most in the coverage gap are concentrated in four states (TX, FL, GA and NC) where eligibility levels for parents in Medicaid are low, and there is no coverage pathway for adults without dependent children. Half of those in the coverage gap are working and six in 10 are people of color.

CBO estimates that provisions to address the coverage gap would result in 1.7 million fewer uninsured people.

budgetary impact

CBO estimates that the net federal cost of extending Marketplace coverage to certain low-income people would increase federal spending by $57 billion over the next decade (this reflects $43.8 billion in federal costs and a loss of federal revenues of $13.2 billion).

CBO estimates provisions to limit DSH and uncompensated care pool funding for non-expansion states would reduce federal costs by $18.3 billion over 5 years and $34.5 billion over the next 10 years and federal costs would increase by $10.4 billion due to the increase in the match rate for current expansion states from 90% to 93% for expansion states for 2023 through 2025.

(Back to top)

6. Maternity Care and Postpartum Coverage

background

Medicaid currently covers almost half of births in the U.S. Federal law requires that pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage last through 60 days postpartum. After that period, some may qualify for Medicaid through another pathway, but others may not qualify, particularly in non-expansion states. In an effort to improve maternal health and coverage stability and to help address racial disparities in maternal health, a provision in the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 gives states a new option to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months. This new option takes effect on April 1, 2022 and is available to states for five years.

provision description

Section 30721 of the Build Back Better Act would require states to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage from 60 days to 12 months, ensuring continuity of Medicaid coverage for postpartum individuals in all states. This requirement would take effect in the first fiscal quarter beginning one year after enactment and also applies to state CHIP programs that cover pregnant individuals.

Section 30722 would create a new option for states to coordinate care for Medicaid-enrolled pregnant and post-partum individuals through a maternal health home model. States that take up this option would receive a 15% increase in FMAP for care delivered through maternal health homes for the first two years. States that are interested in pursuing this new option can receive planning grants prior to implementation.

Sections 31031 through 31048 of the Build Back Better Act provide federal grants to bolster other aspects of maternal health care. The funds would be used to address a wide range of issues, such as addressing social determinants of maternal health; diversifying the perinatal nursing workforce, expanding care for maternal mental health and substance use, and supporting research and programs that promote maternal health equity.

people affected

Largely in response to the new federal option, at least 26 states have taken steps to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage. Pregnant people in non-expansion states could see the biggest change as they are more likely than those in expansion states to become uninsured after the 60-day postpartum coverage period. For example, in Alabama, the Medicaid eligibility level for pregnant individuals is 146% FPL, but only 18% FPL (approximately $4,000/year for a family of three) for parents.

Some states have piloted maternal health homes and seen positive impacts on health outcomes. The federal grant provisions related to maternal health could affect care for all persons giving birth, but the focus of these proposals is on reducing racial and ethnic inequities. There were approximately 3.7 million births in 2019, and nearly half were to women of color. There are approximately 700-800 pregnancy-related deaths annually, with the rate 2-3 times higher among Black and American Indian and Alaska Native women compared to White women. Additionally, there are stark racial and ethnic disparities in other maternal and health outcomes, including preterm birth and infant mortality.

budgetary impact

CBO estimates that requiring 12 month postpartum coverage in Medicaid and CHIP would have a net federal cost of $1.2 billion over 10 years (new costs of $2.2 billion offset by new revenues of $1.0 billion. CBO estimates that the option to create a maternal health home would increase federal spending by $1.0 billion over 10 years.

CBO estimates that federal outlays for the grant sections in the Build Back Better Act related to maternal health care outside of the postpartum extension and maternal health homes are $1.1 billion.

(Back to top)

7. Other Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance (CHIP) Changes

background

Under current law, states have the option to provide 12-months of continuous coverage for children. Under this option, states allow a child to remain enrolled for a full year unless the child ages out of coverage, moves out of state, voluntarily withdraws, or does not make premium payments. As such, 12-month continuous eligibility eliminates coverage gaps due to fluctuations in income over the course of the year.

To help support states and promote stability of coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) provides a 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal share of certain Medicaid spending, provided that states meet maintenance of eligibility (MOE) requirements that include ensuring continuous coverage for current enrollees.

Under current law, Medicaid is the base of coverage for low-income children. CHIP complements Medicaid by covering uninsured children in families with incomes above Medicaid eligibility levels. Unlike Medicaid, federal funding for CHIP is capped and provided as annual allotments to states. CHIP funding is authorized through September 30, 2027. While CHIP generally has bipartisan support, during the last reauthorization funding lapsed before Congress reauthorized funding.

provision description

Section 30741 of the Build Back Better Act would require states to extend 12-month continuous coverage for children on Medicaid and CHIP.

Section 30741 of the Build Back Better Act would phase out the FFCRA enhanced federal funding to states. States would continue to receive the 6.2 percentage point increase through March 31, 2022, followed by a 3.0 percentage point increase from April 1, 2022 through June 30, 2022, and a 1.5 percentage point increase from July 1, 2022 through September 30, 2022.

Section 30741 also would modify the FFCRA MOE requirement for continuous coverage. From April 1 through September 30, 2022, states could continue receiving the enhanced federal matching funds if they only terminate coverage for individuals who are determined no longer eligible for Medicaid and have been enrolled at least 12 consecutive months. The legislation includes other rules for states about conducting eligibility redeterminations and when states can terminate coverage.

Section 30801 of the Build Back Better Act would permanently extend the CHIP program.

people affected

As of May 2021, there were 39 million children enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP (nearly half of all enrollees). As of January 2020, 34 states provide 12-month continuous eligibility to at least some children in either Medicaid or CHIP. A recent MACPAC report found that the overall mean length of coverage for children in 2018 was 11.7 months, and also that rates of churn (in which children dis-enroll and reenroll within a short period of time) were lower in states that had adopted the 12-month continuous coverage option and in states that did not conduct periodic data checks. Another recent report shows that children with gaps in coverage during a year are more likely to be children of color with lower incomes.

As of May 2021, there were 6.9 million people (mostly children) enrolled in CHIP.

budgetary impact

CBO estimates that Section 30741 would reduce federal costs by a net $3.5 billion over 10 years. This 10 year number reflects $17.1 billion in federal savings in FY 2022 that is likely related to the provisions to end the enhanced fiscal relief and the continuous coverage requirements and then federal costs starting in FY 2024. CBO estimates that permanently extending the CHIP program would reduce federal costs by $1.2 billion over 10 years.

(Back to top)

8. Other Medicaid Financing and Benefit Changes

background

Unlike in the 50 states and D.C., annual federal funding for Medicaid in the U.S. Territories is subject to a statutory cap and fixed matching rate. The funding caps and match rates have been increased by Congress in response to emergencies over time.

Vaccines are an optional benefit for certain adult populations, including low-income parent/caretakers, pregnant women, and persons who are eligible based on old age or a disability. For adults enrolled under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and other populations for whom the state elects to provide an “alternative benefit plan,” their benefits are subject to certain requirements in the ACA, including coverage of vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) with no cost sharing.

Under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, coverage of testing and treatment for COVID-19, including vaccines, is required with no cost sharing in order for states to access temporary enhanced federal funding for Medicaid which is tied to the public health emergency. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) clarified that coverage of COVID-19 vaccines and their administration, without cost sharing, is required for nearly all Medicaid enrollees, through the last day of the 1st calendar quarter beginning at least 1 year after the public health emergency ends. The ARPA also provides 100% federal financing for this coverage.

provision description

Section 30731 of the Build Back Better Act would increase the Medicaid cap amount and match rate for the territories. The FMAP would be permanently adjusted to 83% for the territories beginning in FY 2022, except that Puerto Rico’s match rate would be 76% in FY 2022 before increasing to 83% in FY 2023 and subsequent years. The legislation would also require a payment floor for certain physician services in Puerto Rico with a penalty for failure to establish the floor.

Section 30751 of the Build Back Better Act would establish a 3.1 percentage point FMAP reduction from October 1, 2022 through December 31, 2025 for states that adopt eligibility standards, methodologies, or procedures that are more restrictive than those in place as of October 1, 2021 (except the penalty would not apply to coverage of non-pregnant, non-disabled adults with income above 133% FPL after December 31, 2022, if the state certifies that it has a budget deficit).

Section 139405 of the Build Back Better Act would require state Medicaid programs to cover all approved vaccines recommended by ACIP and vaccine administration, without cost sharing, for categorically and medically needy adults. States that provide adult vaccine coverage without cost sharing as of the date of enactment would receive a 1 percentage point FMAP increase for 8 quarters.

people affected

In June 2019 there were approximately 1.3 million Medicaid enrollees in the territories (with 1.2 million in Puerto Rico).

From February 2020 through May 2021 Medicaid and CHIP enrollment has increased by 11.5 million or 16.2% due to the economic effects of the pandemic and MOE requirements.

All states provide some vaccine coverage for adults enrolled in Medicaid who are not covered as part of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, but as of 2019, only about half of states covered all ACIP-recommended vaccines.

budgetary impact

CBO estimates that the changes in Medicaid financing for the Territories would increase federal spending by $9.5 billion over 10 years.

CBO estimates that the provision to impose a penalty in the match rate if states implement eligibility or enrollment restrictions through 2025 would increase federal costs by $7.0 billion.

CBO estimates that extending vaccines to adults on Medicaid would increase federal spending by $2.8 billion over 10 years.

(Back to top)

9. Medicaid Home and Community Based Services and the Direct Care Workforce

background

Medicaid is currently the primary payer for long-term services and supports (LTSS), including home and community-based services (HCBS), that help seniors and people with disabilities with daily self-care and independent living needs. There is currently a great deal of state variation as most HCBS eligibility pathways and benefits are optional for states.

PROVISION DESCRIPTION

Sections 30711-30713 of the Build Back Better Act would create the HCBS Improvement Program, which would provide a permanent 6 percentage point increase in federal Medicaid matching funds for HCBS. To qualify for the enhanced funds, states would have to maintain existing HCBS eligibility, benefits, and payment rates and have an approved plan to expand HCBS access, strengthen the direct care workforce, and monitor HCBS quality. The bill includes some provisions to support family caregivers. In addition, the Act would include funding ($130 million) for state planning grants and enhanced funding for administrative costs for certain activities (80% instead of 50%).

Section 30714 of the Build Back Better Act would require states to report HCBS quality measures to HHS, beginning 2 years after the Secretary publishes HCBS quality measures as part of the Medicaid/CHIP core measures for children and adults. The bill provides states with an enhanced 80% federal matching rate for adopting and reporting these measures.

Sections 30715 and 30716 of the Build Back Better Act would make the ACA HCBS spousal impoverishment protections and the Money Follows the Person (MFP) program permanent.

Sections 22301 and 22302 of the Build Back Better Act would provide $1 billion in grants to states, community-based organizations, educational institutions, and other entities by the Department of Labor Secretary to develop and implement strategies for direct service workforce recruitment, retention, and/or education and training.

Section 25005 of the Build Back Better Act would provide $20 million for HHS and the Administration on Community Living to establish a national technical assistance center for supporting the direct care workforce and family caregivers.

Section 25006 of the Build Back Better Act would provide $40 million for the HHS Secretary to award to states, nonprofits, educational institutions, and other entities to address the behavioral health needs of unpaid caregivers of older individuals and older relative caregivers.

people affected

The majority of HCBS are provided by waivers, which served over 2.5 million enrollees in 2018. There is substantial unmet need for HCBS, which is expected to increase with the growth in the aging population in the coming years. Nearly 820,000 people in 41 states were on a Medicaid HCBS waiver waiting list in 2018. Though waiting lists alone are an incomplete measure, they are one proxy for unmet need for HCBS. Additionally, a shortage of direct care workers predated and has been intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic, characterized by low wages and limited opportunities for career advancement. The direct care workforce is disproportionately female and Black.

A KFF survey found that, as of 2018, 14 states expected that allowing the ACA spousal impoverishment provision to expire would affect Medicaid HCBS enrollees, for example by making fewer individuals eligible for waiver services.

Over 101,000 seniors and people with disabilities across 44 states and DC moved from nursing homes to the community using MFP funds from 2008-2019. A federal evaluation of MFP showed about 5,000 new participants in each six month period from December 2013 through December 2016, indicating a continuing need for the program.

Budgetary Impact

CBO estimates that all of the Medicaid-related HCBS provisions together will increase federal spending by about $150 billion in the 10-year budget window. The new HCBS Improvement Program (Section 30712) accounts for most of this spending ($146.5 billion).

CBO scores the Department of Labor direct care workforce provisions according to the amount of spending authorized for each in the bill: $1 billion for grants to support the direct care workforce (Section 22302), $20 million for a technical assistance center for supporting direct care and caregiving (Section 25005), and $40 million for funding to support unpaid caregivers (Section 25006).

(Back to top)

10. Paid Family and Medical Leave

background

The U.S. is the only industrialized nation without a minimum standard of paid family or medical leave. Although six states and DC have paid family and medical leave laws in effect, and some employers voluntarily offer these benefits, this has resulted in a patchwork of policies with varying degrees of generosity and leaves many workers without a financial safety net when they need to take time off work to care for themselves or their families.

provision description

Section 130001 of the Build Back Better Act would guarantee four weeks per year of paid family and medical leave to all workers in the U.S. who need time off work to welcome a new child, recover from a serious illness, or care for a seriously ill family member. Annual earnings up to $15,080 would be replaced at approximately 90% of average weekly earnings, plus about 73% of average weekly earnings for annual wages between $15,080 and $32,248, capping out at 53% of average weekly earnings for annual wages between $32,248 and $62,000. While all workers taking qualified leave would be eligible for at least some wage replacement, the progressive benefits formula means that the share of pay replaced while on qualified leave is highest for workers with lower wages. The original Act called for 12 weeks of paid leave for similar qualified reasons, plus three days of bereavement leave, and benefits began at 85% of average weekly earnings for annual wages up to $15,080 and were capped at 5% of average weekly earnings for annual wages up to $250,000.

people affected

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), approximately one in four (23%) workers has access to paid family leave through their employer. Data on the share of workers with access to paid medical leave for their own longer, serious illness are limited, although BLS also reports that 40% of workers have access to short-term disability insurance.

It is estimated that 53 million adults are caregivers for a dependent child or adult and 61% of them are women. Sixty percent (60%) of caregivers reported having to take a leave of absence leave from work or cut their hours in order to care for a family member. Workers who take leave do so for different reasons: Half (51%) reported taking leave due to their own serious illness, one-quarter (25%) for reasons related to pregnancy, childbirth, or bonding with a new child, and one-fifth (19%) to care for a seriously ill family member. In total, four in ten (42%) reported receiving their full pay while on leave, one-quarter (24%) received partial pay, and one-third (34%) received no pay.

budgetary impact

CBO estimates that the federal cost of these provisions would be about $205.5 billion over the 2022-2031 period. The estimate accounts for funding the paid leave benefits and administration, grants for the state administration option for states that already have a comprehensive paid leave law, and partial reimbursements for employers that provide equally comprehensive paid leave as a benefit to all their workers. The CBO estimate is modestly offset by application fees paid by employers participating in the reimbursement option for employer-sponsored paid leave benefits.

(Back to top)

11. Consumer Assistance, Enrollment Assistance, and Outreach

background

Consumer Assistance in Health Insurance – The Affordable Care Act (ACA) established a new system of state health insurance ombudsman programs, also called Consumer Assistance Programs, or CAPs. These programs are required to conduct public education about health insurance consumer protections and help people resolve problems with their health plans, including filing appeals for denied claims. By law, private health plans, including employer-sponsored plans, are required to include contact information for CAPs on all explanation-of-benefit statements (EOB) with notice that CAPs can help consumers file appeals.

To help inform oversight, CAPs are also required to report data to the Secretary of HHS on consumer experiences and problems. The ACA permanently authorized CAPs and appropriated seed funding of $30 million in 2010. Forty state CAPs were established that year; since then, Congress has not appropriated CAP funding.

Enrollment Assistance and Outreach in the Marketplace – The Affordable Care Act also requires marketplaces to establish Navigator programs that help consumers apply for and enroll in coverage through the marketplace. And it requires marketplaces to conduct public education and outreach about the availability of coverage and financial assistance. As noted above, the Build Back Better Act would create new eligibility for marketplace coverage and financial assistance for low-income adults in states that have not expanded Medicaid.

provision description

Section 30603 appropriates $100 million for state consumer assistance programs (CAPs) over the 4-year period, 2022-2025.

Section 30601(d) appropriates $105 million to conduct public education and outreach in non-expansion states so people will learn about new coverage and subsidy options. $15 million is appropriated for 2022 and $30 million for each of 2023-2025. In addition, this section requires the Secretary to obligate no less than $70 million of marketplace user-fee revenues for additional Navigator funding to support enrollment assistance for the new coverage-gap population (at least $10 million in FY 2022 and at least $20 million in each of FY 2023-2025).

people affected

CAP Funding – More than 175 million Americans are covered by private health insurance plans today. Consumers generally find health insurance confusing and have limited understanding of even basic health insurance terms and concepts. Four-in-ten have difficulty understanding what their health plan will cover or how much they will have to pay out-of-pocket for needed care; when faced with unaffordable bills, only one-in-ten even try to get providers to lower their price. When claims are denied, consumers rarely appeal. These are the kinds of problems CAPs could help address with expanded funding. Most of the state CAPs established in 2010 continue to operate today, though at reduced capacity without federal financial support; programs rely on state funding (many CAPs are housed in state Insurance Departments or Attorney General offices) and philanthropic support today. With recent enactment of the federal No Surprises Act, as well as amendments to the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA), CAPS can help consumers understand and navigate new federal health insurance protections and inform oversight by federal and state agencies.

Marketplace Enrollment Assistance and Outreach – After years of cuts in funding for Navigator enrollment assistance and outreach, the Biden Administration took steps this year to restore federal marketplace funding for these activities. During the 2021 COVID special enrollment opportunity, when expanded subsidies enacted by ARPA first became available, more than 2.2 million people newly signed up for marketplace coverage. However, KFF found only 1 in 4 people who are uninsured or buy their own health insurance checked to see if they would qualify for affordable coverage. This finding is consistent with earlier KFF surveys that find 3 in 4 uninsured don’t look for health coverage because they assume it is not affordable. Investments in public education, outreach, and enrollment assistance can help inform the 2.2 million uninsured adults in the coverage gap of new affordable health coverage options through the marketplace.

budgetary impact

New appropriations for Consumer Assistance Programs would cost $100 million over 5 years.

New appropriations for marketplace outreach would cost $105 million over 5 years. Additional funding for Navigator enrollment assistance in coverage gap states would not come from new appropriations; these resources will come from user fee revenue collected by the marketplace.(Back to top)