Potential Implications of Policy Changes in Medicaid Drug Purchasing

Introduction

Prescription drug spending has again returned to the policy agenda, with Congress and the Administration developing proposals to target drug prices. Though attention in current federal actions is largely focused on Medicare drug prices, federal legislation also has been recently introduced or enacted that would affect Medicaid prescription drug policy. In addition, some Medicaid drug pricing policies could be included in upcoming legislation that aims to expand coverage, particularly if the policies provide spending offsets. In response to increased spending on high-cost specialty drugs, the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) recently adopted policy recommendations to Congress related to the Medicaid drug benefit. While drug costs have been a focus for state Medicaid programs even before the COVID-19 fiscal crisis, there may be renewed state interest in examining policy options that would reduce Medicaid drug spending to address fiscal constraints and meet demands for other pandemic-related spending. As of March 2021, 14 states had introduced 17 bills that included provisions related to Medicaid prescription drug costs, and states are also pursuing a range of administrative actions in this area.

Medicaid provides health coverage for millions of Americans, including many with substantial health needs who rely on Medicaid drug coverage both for acute problems and for managing ongoing chronic or disabling conditions. Though the pharmacy benefit is a state option, all states provide pharmacy benefit coverage. States administer the benefit in different ways within federal guidelines regarding, for example, pricing, utilization management, and rebates. Due to federally required rebates, Medicaid pays substantially lower net prices for drugs than Medicare or private insurers. After high rates of growth from 2014-16 due to specialty drug costs and coverage expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Medicaid drug spending growth slowed from 2017-2018; however, drug spending growth increased again in 2019, and policymakers remain concerned about Medicaid prescription drug spending as new, curative therapies enter the market.

Medicaid drug policy involves several entities with an interest in this issue: state and federal governments are payers, reimbursing pharmacies and (indirectly) manufacturers for the cost of drugs for beneficiaries; pharmacies purchase drugs from manufacturers or wholesalers, dispense drugs, and receive a dispensing fee and payment for the cost of the drug; manufacturers set prices for drugs and sell these to wholesalers or pharmacies; managed care organizations (MCOs) and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) play a role in negotiating prices and utilization management for drugs. Policies to target one component of this complex supply and payment chain are likely to have implications and invoke behavioral responses to changes throughout the system.

This brief examines how leading federal and state policy options related to changes in Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), drug pricing, and payment and management of the Medicaid prescription drug would affect state and federal governments as well as private industry (including drug manufacturers, managed care organizations, and pharmacies). It discusses potential federal and state policy changes in three areas: policies that increase Medicaid drug rebates, policies that increase price transparency, and policies that target drug prices.1

Effects of Policies to Increase Rebates

While Medicaid rebates already provide a significant offset to the program’s drug spending, several policy proposals aim to further increase drug rebates in Medicaid. The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), established under federal law, includes two main components: a rebate based on a percentage of average manufacturer price (AMP) or the largest “best price” discount provided to most private purchasers, and an inflationary component to account for price increases.2 States can negotiate rebates in addition to the statutory rebate, referred to as supplemental rebates, and often use placement on their preferred drug list (PDL) as leverage to do so. Manufacturer rebates accounted for 56% of gross Medicaid drug spending in 2019. 3 For certain brand name drugs, Medicaid rebates were higher— on average, statutory rebates were 77 percent of Medicaid retail price in 2017, with the inflationary rebate component accounting for about half of the total discount.4 Several policy approaches increase statutory rebates or state supplemental rebates even more. These specific policies differ in how they can be implemented (federal vs state policy change) and in some of the potential effects for stakeholders. However, in general, they would lead to savings for government buyers and lower reimbursement for manufacturers.

Policies to Increase Statutory Rebates

Policies to increase rebates under MDRP include a range of actions targeted to launch prices, high-cost specialty drugs, and loopholes and gaming. These policies aim to address several issues with MDRP. First, the MDRP formula does not explicitly address launch prices or currently high-priced drugs. Second, the rebate formula varies by type of drug, with a higher rebate for brand drugs than for generics, and thus enables some gaming or flexibility in how drugs are classified. The rebate calculations rely on the pricing information reported by manufacturers; misclassified drugs or inaccurate price information in these files affects the rebate calculation, and improving the accuracy of information would ensure appropriate rebates are paid and allow for penalties for reporting inaccurate information. Proposals to increase the statutory rebate include increasing the minimum rebate percentage based on launch price, increasing the minimum rebate for certain high-cost specialty drugs, increasing the inflationary rebate; implementing price enforcement mechanisms to improve accuracy of information used to calculate rebates; and closing loopholes that enable manufacturers to lower rebate obligations. These actions build on recent federal action that lifts the rebate cap (currently set at 100% of AMP until 2024). Such changes require Congressional action to amend federal Medicaid law.

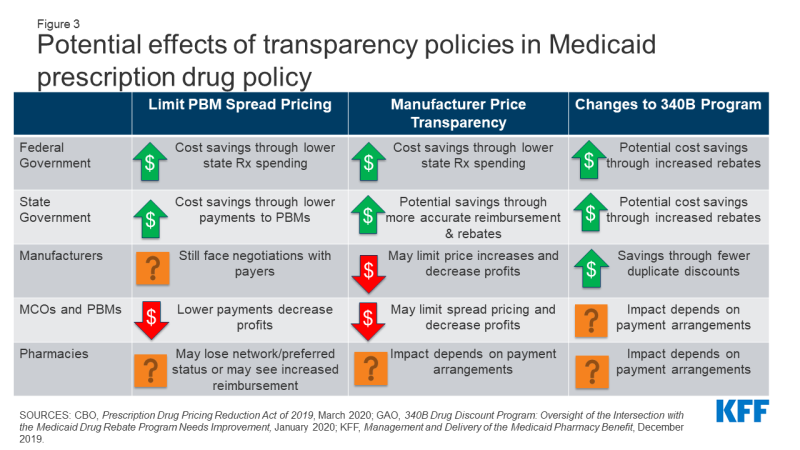

Increases to statutory rebates reduce federal Medicaid spending through lower net reimbursement to manufacturers (Figure 2). For example, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that recent action to remove the cap on inflationary rebates will increase the amount of rebates that manufacturers pay Medicaid and would reduce federal spending in Medicaid by $14.5 billion over the 2021-2030 period.

Figure 2: Potential effects of changes to Medicaid prescription drug purchasing to increase rebates.

The effect of changes to MDRP on state spending is dependent on how the policy is structured. In general, states and the federal government share in rebates. However, increases in statutory rebates passed as part of the ACA specifically excluded states from receiving a share of the increased rebate.5 Thus, depending on the policy, states may not share in increases to statutory rebates. Increases in federal rebates also could lead to lower state supplemental rebates, as manufacturers may be less willing to offer additional rebates beyond MDRP. 6, 7 State actions to negotiate or maintain supplemental rebates, discussed in detail below, could counter this effect.

It is highly unlikely, though possible, that some manufacturers would opt out of the MDRP due to very low net Medicaid reimbursement. Manufacturers must opt in or out of the MDRP for all of their products, not just one, and participation in MDRP also impacts eligibility for Medicare Part B reimbursement. A recent analysis of net prices in several government programs concluded that, though Medicaid net prices were close to zero for some drugs, manufacturers have calculated that the increased revenue from other payers offsets the loss in revenue from Medicaid.8

Effects of changes to MDRP on drug prices or costs to other payers are dependent on manufacturer decisions and other payers’ negotiating power. For example, the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) included an increase in the base MDRP rebate amount, and analysis at the time concluded that manufacturers would increase launch prices (but the policy would still generate overall savings for Medicaid). Past analysis also indicated that manufacturers may increase prices to other payers in response to increased statutory Medicaid rebates, though those purchasers may be able to offset these increases by negotiating discounts with manufacturers.9 Subsequent research has had mixed findings on how the increase in base rebate led to other pricing responses, and specific Medicaid rebate proposals could target other aspects of pricing such as launch price. Manufacturers maintain that policies to increase Medicaid rebates create incentives to raise prices and may shift costs to other payers.10

Implications for MCOs and pharmacies of many proposals in this area are uncertain and depend on how a specific policy is structured. To the extent that changes affect both prices paid to pharmacies by state Medicaid programs and pharmacies’ costs to acquire the drug, net changes to pharmacies could be neutral. However, efforts to recoup lost profit or lost savings through changes to dispensing fees could affect pharmacies.

Policies to Increase Supplemental Rebates

States efforts to increase supplemental rebate agreements generally aim to increase purchasing power or other leverage in negotiation with manufacturers. State supplemental rebates account for a small share (6% in 2019)11 of total rebates collected in Medicaid, in part reflecting lower state negotiating power. States generally share savings from supplemental rebates with the federal government. While approximately two-thirds of the states with supplemental rebate programs (30 of 46 states) have entered into multi-state purchasing pools to enhance their negotiating leverage and collections, other options to increase leverage include a national pool, intra-state (cross-agency) negotiation, or inclusion of drugs covered through Medicaid managed care. For example, California has announced plans to pool purchasing power across Medicaid and other agencies to receive higher discounts, and Louisiana has a supplemental rebate agreement that also ensures access for incarcerated individuals.12,13

Other actions to increase supplemental rebates draw on states’ control of preferred drug lists (PDLs) or other utilization control measures. Since supplemental rebates are not included in the best price calculation that impacts manufacturer statutory rebate obligations, states may be able to negotiate supplemental rebates for high cost specialty drugs without manufacturer concern over system-wide effects on prices. Some states have negotiated “value based payment” models that lead to higher supplemental rebates and predictability in spending.14 For example, Louisiana’s “subscription model” supplemental rebate agreement caps the state’s expenditures on the drug covered under the arrangement during the term of the agreement.15 Other proposals would use outcomes-based contracts, similar to those negotiated by Oklahoma.

Lastly, other proposals aim to increase state-negotiated supplemental rebates by extending them to all drugs or by adding an inflationary component to supplemental rebates (similar to the inflationary component of statutory rebates). However, state ability to negotiate supplemental rebates is hampered by manufacturer willingness to provide rebates beyond statutory rebates, particularly when Medicaid programs are required under the MDRP to cover all their drugs.

Supplemental rebates may lead to state savings, but it is unclear how much states can increase supplemental rebates to achieve substantial savings. If states are able to pool purchasing power with other agencies, they could see state savings in other health spending programs (e.g., state employees, prisons, substance use programs, etc.). However, while state supplemental agreements may lower costs or allow predictability in costs, it is unclear how much states will be able to negotiate in light of recent changes to the statutory rebate. After growing at double digits in the early 2000s,16 state supplemental rebates were relatively flat or decreasing after the 2010 changes to the MDRP, perhaps reflecting manufacturer unwillingness to offer additional rebates within Medicaid. On the other hand, state supplemental rebates increased in 2018 and 201917, perhaps reflecting successful strategies to procure targeted rebates on high cost drugs. The specifics of state supplemental agreements are generally proprietary, and it is difficult to know how much states save through a particular agreement.

Efforts that carve out prescription drugs from MCO contracts to capture all supplemental rebates and concentrate negotiating power may increase reliance on brand-name drugs over generics. A majority of states use comprehensive managed care arrangements that include prescription drugs as a covered benefit. States that move to carve out this benefit to increase state negotiating power may change drug utilization patterns. Generally, MCOs promote somewhat greater use of generic drugs than FFS Medicaid, but generics may not always be the lowest net cost drug due to the rebates Medicaid receives.18,19 An increase in use of brand drugs could lead to higher gross costs, but the state would see a corresponding increase in rebates, as rebates on brand drugs are proportionately higher than generic and sometimes lead to lower net costs.

Some state actions to capture additional supplemental rebates may carry new administrative costs. For example, state efforts to coordinate prescription drug purchasing across state agencies may require extensive planning and coordination costs.20 In addition, states may face additional administrative costs if they manage the pharmacy benefit rather than outsource management to MCOs, though loading fees to MCOs would also decline.

The impact of increased supplemental rebates on MCOs or PBMs depends on current state policy and the structure of the rebate agreement. As part of a policy to increase supplemental rebates, states may require MCOs and PBMs to pass through supplemental rebates or may prohibit MCOs or PBMs from negotiating additional rebates at all. Reducing or eliminating rebates could lower profits for MCOs, depending on how those rebates are accounted for in capitation payments. Under carve-out arrangements, MCOs may experience increased costs due to coordination challenges with FFS or delays in accessing pharmacy data to manage enrollee health. Because many MCOs outsource administration of the pharmacy benefit to PBMs, carving out also would lead to lower PBM revenue through loss of contracts. States may choose to contract with PBMs through FFS, but FFS payment policies may limit PBMs’ ability to use spread pricing.

If states carve out prescription drugs to increase leverage for supplemental rebates, reimbursement to pharmacies could change. Drugs provided through FFS arrangements must be reimbursed at actual acquisition cost (AAC), defined as the state Medicaid agencies’ determination of pharmacy providers’ actual prices paid to acquire drugs. MCOs are not required to base reimbursements on AAC and therefore a shift to FFS could increase or decrease payment, depending on how MCOs paid prior to the carve out.

Effects of Policies to Increase Transparency

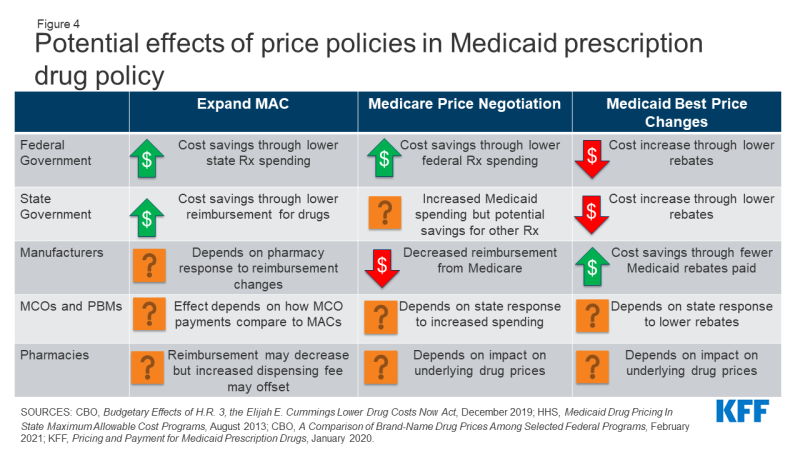

Lack of transparency through the prescription drug pricing process, both in general and specifically within Medicaid, has led to several proposed policies that aim to provide accurate and public information on drug pricing. Medicaid payments for drugs are based on several drug pricing benchmarks or negotiated prices, some of which are known only to the parties involved in the transaction. In addition, manufacturers do not provide public information on how they set list prices, and specific rebate amounts are considered proprietary. Further, increased reliance on pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) poses challenges to drug price transparency.21 The prices PBMs pay manufacturers and reimbursement they pay pharmacies are often unknown. These issues make understanding of actual costs and spending drivers a challenge. Policy approaches to address this challenge include limiting PBM spread pricing, increasing manufacturer transparency and changes to the 340B program (Figure 3). Policies to increase transparency may be implemented at the state or federal level, and the implications may differ based on how the policy is implemented.

Policies to Limit PBM Spread Pricing

Increased concern over spread pricing by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) has led to state and federal proposals or policies to limit or ban such practices. PBMs help administer drug benefits and take on financial responsibilities such as negotiating prescription drug rebates with manufacturers and dispensing fees with pharmacies. Spread pricing refers to the difference between the payment the PBM receives from the state or MCO and the reimbursement amount it pays to the pharmacy. States are increasingly taking action to monitor and regulate PBM spread pricing, with 15 states reporting laws in place or planned for 2019 and 2020. States can enact legislation banning spread pricing outright or placing other requirements on PBMs that contract with the Medicaid program. States also can place stipulations on contracts with MCOs to not contract with PBMs that use spread pricing. Other policy proposals to limit spread pricing include implementing reporting requirements on PBM reimbursement. The federal government also could enact legislation regulating PBMs more broadly by prohibiting or limiting spread pricing in the Medicaid program and has increasingly shown interest in oversight of PBMs.

Estimates of spread pricing or the effect of bans on it vary widely, making the scale of the cost savings to Medicaid difficult to predict. Overall, limiting spread pricing would likely decrease net federal and state spending through lower payments to MCOs or PBMs. If PBMs and MCOs were required to pass through any savings, states spending for prescription drugs could decline by the spread price amount. Further, the federal government may indirectly share in savings because Medicaid drug costs are jointly financed by state and federal funds. A number of states have conducted analyses finding high amounts of spread on generic drugs and estimating state savings in the millions if spread pricing is eliminated, but it is not clear to what extent these findings are generalizable to other states. An analysis by CBO of federal legislation to ban spread pricing estimated federal savings of $929 million nationwide between 2021-2030.

The overall effect of limiting PBM spread pricing on manufacturers is uncertain, as PBMs retain some incentives to negotiate discounts. PBMs generally use leverage and PDL management to negotiate lower prices from manufacturers and generally incentivize use of generic drugs.22 While PBMs would no longer retain these savings as spread pricing, they may still have an incentive to negotiate lower manufacturer prices due to the need to compete for contracts. Because research has shown that PBMs generate higher spread on generic drugs than brand drugs, elimination of spread pricing may mean PBMs may have less of an incentive to prioritize generic drugs.23,24,25 Manufacturers could see an increase in revenue due to increased brand drug usage but also would likely pay more in rebates to Medicaid.

Eliminating or limiting spread pricing could lead to increased reimbursement to pharmacies, depending on how PBMs change their negotiating tactics with pharmacies. PBMs often negotiate with pharmacies to create “network” pharmacies, driving business to pharmacies and allowing PBMs to negotiate lower payment rates to pharmacies (and thus increase their spread). Pharmacy reimbursement to network pharmacies may increase without PBM incentive to create spread, and other pharmacies may see increased business due to decreased PBM incentives to create pharmacy networks.

Policies to Increase Manufacturer Price Transparency

A range of federal and state policy proposals aim to make information about list prices more accessible in an effort to curb drug costs. Drug list prices affect not only the reimbursement paid to the pharmacy but also the rebates the Medicaid program receives. Manufacturers do not provide public information on how they set list prices and historically have not been required to explain changes in a product’s list price. Price transparency policies aim to make pricing information public to identify cost drivers, provide evidence for policy makers, or sometimes apply public pressure to get payers to lower prices.

Most action on manufacturer price transparency has been taken at the state level. State policies range from acquiring price information on all drugs to requiring reporting for drugs with high cost increase. The limits of state regulatory power over pharmaceutical companies are not clear, and manufacturers often challenge state laws in court.26 Federal policies related to price transparency include making National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC, a federal survey of pharmacies that helps states to determine pharmacy acquisition cost) mandatory and increasing the amount of information collected by the survey; requiring manufacturer reporting; and price transparency of Wholesale Average Cost (WAC) and Average Manufacturer Price (AMP). Some federal administrative actions (e.g., the Trump administration’s rule to require drug pricing in pharmaceutical television advertising) have been blocked in court,27 and legislative action may be needed to establish authority for some specific policies.

To date, the impact of transparency on actual prices is uncertain, making it difficult to predict changes to state or federal Medicaid drug spending. So far, most states with transparency or reporting laws are at the initial stages of reporting price data but have not reported impact on prices. An analysis by CBO estimates no federal savings from price transparency provisions that would require manufacturers to justify price increases on certain drugs. However, to the extent that transparency allows policymakers to target cost-saving actions (for example, by placing caps on price increases), such policies could potentially lead to lower federal and state spending for Medicaid prescription drugs. Increased transparency around WAC and NADAC may allow states to more accurately reimburse pharmacies for acquisition costs. Transparency could also allow for better enforcement of the MDRP by increased accuracy of price reporting, which could reduce state and federal net drug spending by increasing rebate amounts.

The impact of transparency on manufacturers would depend on manufacturer behavior and response to reporting requirements.28 Reporting requirements could increase public pressure to lower prices for drugs subject to reporting or review, though it is not clear whether manufacturers would respond to this pressure. Transparency could also allow for better enforcement of the MDRP and increased state leverage in supplemental rebate negotiations, which would increase manufacturer payments to states and the federal government.

Increased price transparency may also limit PBM ability to use spread pricing, outside of efforts directly target spread pricing. If prices are publicly known or reported to state agencies, states may demand PBM pricing closer to actual costs.29

Policies to Limit or Monitor the 340B Program

Concerns over program integrity of the 340B program, which provides discounted drugs to certain safety net providers, have led to proposed policy changes to limit the program or require additional oversight and reporting. As a condition of participation in the MDRP, manufacturers must also participate in the federal 340B program, which offers discounted drugs to certain safety net providers, known as covered entities (CEs), that serve vulnerable or underserved populations in order to maximize use of federal resources. CEs pay a deeply-discounted “ceiling price” to manufacturers for prescription drugs. The 340B program is administered separately from the MDRP, and federal law requires states and safety net providers to ensure that manufacturers do not pay duplicate discounts for Medicaid beneficiaries. States may set guidelines for CEs on whether or not to provide drugs purchased with the 340B program discounts to Medicaid beneficiaries.

The increased use of managed care in administering the pharmacy benefit has led to 340B transparency issues, as 340B drugs covered by MCOs are harder to track and exclude from Medicaid rebate requests.30 Similarly, increased use of contract pharmacies by CEs has made it more difficult to track 340B drugs and ensure duplicate discounts are not occurring.31 Recently, some manufacturers have announced that they will no longer provide discounts on drugs dispensed at 340B contract pharmacies,32 and there is increased attention to whether CEs are buying drugs at the discounted price and selling them at a higher price to Medicaid or other payers. Lastly, the number of covered entities and contract pharmacies has grown dramatically, but the federal government has conducted only limited audits of covered entities and has stated it does not have sufficient enforcement capabilities to ensure program compliance.33 Policies to address transparency in 340B include a moratorium on new CEs as well as increased oversight and reporting requirements. Like other transparency policies, the aim of many 340B efforts is to provide policymakers and others information to target overpayments (or, in this case, duplicate discounts). Others seek to extend 340B pricing, such as a rule finalized by the Trump administration in December 2020 that would have required CEs to pass through 340B pricing on certain drugs to low income people (the rule has been delayed by the Biden administration).

Changes to 340B will directly affect payments to manufacturers and costs paid by CEs. Manufacturers would potentially receive higher payments due to fewer duplicate discounts. Alternatively, manufacturers may pay more rebates to Medicaid programs for drugs dispensed to Medicaid beneficiaries outside of the 340B program, so the overall cost impact is uncertain. In general, 340B entities would see higher costs to acquire drugs. Additional reporting requirements may increase administrative burdens on smaller CEs, reducing their participation in the program.

Limits to the 340B program may result in some state and federal Medicaid savings. Medicaid payments to pharmacies reflect the acquisition cost of a drug plus a professional dispensing fee. For drugs provided to Medicaid beneficiaries through 340B, the acquisition cost reflects the ceiling price and may be lower than costs outside 340B; however, states forego rebates on 340B drugs. Elimination or limits on 340B would thus potentially increase state payments to pharmacies and increase rebates collected, leading to uncertain net effects on Medicaid costs. Other state savings could accrue if states were paying higher 340B dispensing fees (due to add-on fees paid to CEs) or are able to collect supplemental rebates on additional drugs due to increased negotiating power. The federal government would also share in any increased rebates, reducing net federal spending.

The effect of 340B changes on MCO, PBM and pharmacy reimbursement are dependent on a complex network of payment arrangements between these entities. MCO payments to pharmacies do not have to reflect acquisition costs for drugs, so it is unclear what effect limits to 340B will have on plan payments or costs. Pharmacies that dispense 340B drugs may see lower dispensing fees if policies limit the 340B program because they will lose add-on fees that states pay specifically for CEs.34 In addition, limits to 340B that restrict the use of contract pharmacies (which may be retail pharmacies) may reduce revenue for these pharmacies.

Other Potential Effects of Medicaid Drug Policy Changes on the 340B Program35

Other policies that impact Medicaid drug pricing may also have implications for 340B entities. Ceiling price, the price paid by entities in the 340B program for prescription drugs, is currently tied to the Medicaid rebate calculation. A change to the Medicaid rebate formula or inputs may impact the prices paid by 340B entities.36 Policies that impact underlying drug prices may also impact 340B reimbursement if the program’s discount is weakened.

In addition, changes to how states administer the pharmacy benefit may impact 340B entities. Some states have different rules for 340B for drug benefits provided through FFS and MCOs, including guidelines around contract pharmacies and carving in to Medicaid. Duplicate discounts are more prevalent in managed care due to administrative complexity and are easier to prevent when drugs are provided through FFS, so an increase in states carving out pharmacy from managed care may reduce revenue for CEs. States may also choose to carve the 340B program out of Medicaid to reduce coordination issues around duplicate discounts and to provide more leverage to the state in negotiations with drug manufacturers for supplemental rebates.

Effects of Policies to Address Drug Pricing

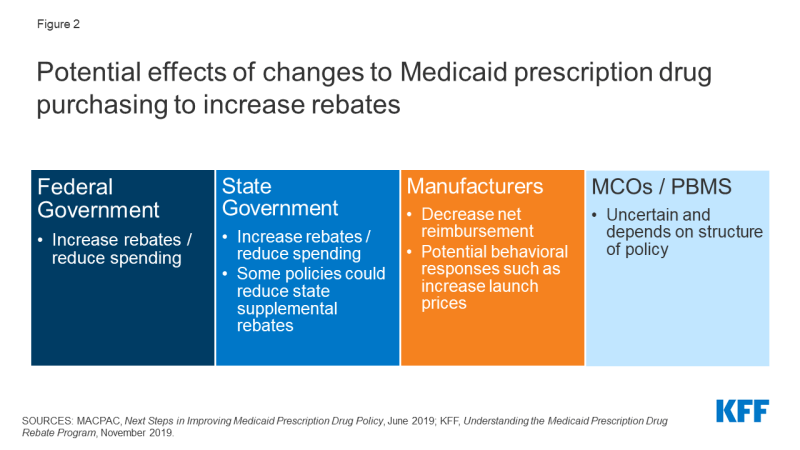

Several other policies under consideration directly target Medicaid drug prices or prices paid by other payers, which would affect Medicaid prices as well. Medicaid payments for prescription drugs are determined by a complex set of policies, at both the federal and state levels, that draw on price benchmarks linked to both drug list prices and acquisition costs for drugs. Because price benchmarks are related to one another, the prices paid throughout the drug distribution process have an effect on the final price that Medicaid pays. Both states and the federal government have price ceilings set for certain drugs, known as Federal Upper Limits (FULs) and Maximum Allowable Costs (MACs), and some proposals target these price ceilings. Others target Medicaid “best price,” largely to allow exceptions for other payers. Although not specifically targeted at Medicaid, policy approaches designed to change the structure of pricing for Medicare or private insurance—such as allowing drug importation or allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices—also have implications for Medicaid. (Figure 4).

Policies to Expand State MAC Programs

Nearly all state Medicaid programs impose price ceilings (state Maximum Allowable Cost, or SMAC) on reimbursement for certain multiple-source (generic) drugs, and some state efforts expand MAC lists to include all generic drugs or apply to managed care. States do not buy drugs directly from manufacturers but instead reimburse pharmacies based on the ingredient cost of the drug, plus a professional dispensing fee. State MAC programs set limits on ingredient costs. They frequently include drugs that do not have established federal upper limits (FULs), which similarly set a federal price ceiling on certain multiple-source drugs.37 States set their own MAC lists for FFS drugs. Currently, MCOs and PBMs are not required to pay based on state MACs and often have their own proprietary MACs. Proposals to expand MAC include increasing the number of drugs on MAC lists as well as extending MAC pricing to MCOs.

In general, expansion of the number of drugs that SMAC applies to could lead states to pay less in drug reimbursement if state MACs for drugs are lower than other price benchmarks. Expanded MACs may reduce the “ingredient cost” portion of pharmacy reimbursement for some drugs depending on state formula. SMACs generally are part of a complex “lesser of” formula for ingredient costs, where the state agency sets reimbursement for multiple-source drugs at the lowest amount for each drug based on (1) the state’s AAC formula, (2) the FUL (if applicable), (3) the state MAC or (4) the pharmacy’s usual and customary charge to the public. Thus, if SMAC is below AAC, the state will have a lower payment amount for the drug. However, if states correspondingly increase pharmacy dispensing costs (as most did when moving to paying based on acquisition cost), much of those savings may be offset. To the extent that states realize savings from pharmacy reimbursement, the federal government would also share in those savings.

The impact of expanded MACs on MCOs and PBMs depends on how proprietary MACs currently paid by PBMs compare to state MACs. If state MACs are lower than current prices paid by MCOs and PBMs, MCO/PBM reimbursement costs would decrease, though states will also reduce capitation payments correspondingly. If state MACs are higher, it would increase payments by MCOs and PBMs to pharmacies. Universal use of MACs may also increase transparency, reducing the ability of PBMs to spread price.

Price ceilings for Medicaid reimbursement to pharmacies for ingredient costs would not directly impact manufacturers unless pharmacies attempted to negotiate lower purchase prices from manufacturers or wholesalers in response to lower reimbursement. To the extent that changes affect both prices paid to pharmacies by state Medicaid programs and pharmacies’ costs to acquire the drug, net changes to pharmacies could be neutral. States may also increase dispensing fee to account for the decrease in reimbursement, as states generally increased dispensing fees when Medicaid reimbursement rules changed.38

Changes to Medicaid Best Price

Medicaid’s rebate formula ensures that the program receives “best price,” but the best price provision is often cited by manufacturers and other stakeholders as a barrier to discounts and value-based contracts for other payers. Under the MDRP, the rebate amount is a defined percent of Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) or the difference between AMP and “best price,” whichever is greater.39 Best price is defined as the lowest available price to any wholesaler, retailer, or provider, excluding certain government programs, such as the health program for veterans. The trend of new, high-cost therapies has created interest in value-based payment arrangements for specific drugs, but manufacturers may be unwilling to enter these agreements for fear of lowering the best price, which would then apply to Medicaid. Proposals to modify best price include allowing exceptions for value-based arrangements, entirely eliminating the best price provision (which may be offset by an increase in the minimum rebate amount) and setting uniform reporting rules for prices under value-based arrangements. Because best price is established under federal law, any changes to its calculation would require federal regulations or legislation.40 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has recently finalized a rule making significant changes to best price reporting, including allowing multiple “best prices,” but the Biden Administration has yet to state its policy on the rule.

Proposals to eliminate best price would generally increase federal and state costs and increase reimbursement for manufacturers. In general, Medicaid rebates for brand name drugs are significantly higher than the minimum rebate amount, and brand drugs account for approximately 80% of gross Medicaid drug spending. Eliminating or modifying best price would reduce rebates closer to the minimum rebate amount and lower rebates received by state and federal government. It is unlikely that states could negotiate supplemental rebate agreements to make up for these lower rebates.41 Manufacturers also will have more flexibility to offer lower prices to different payers, which they would likely only do if their total revenue increased under the arrangement.

If statutory rebates are reduced, MCOs and PBMs may have a larger role to negotiate lower prices or rebates for certain drugs with manufacturers. Reimbursement effects depend on whether the MCO or PBM is required to pass through the additional rebates to the state. States may also carve out the pharmacy benefit or take other actions as described above to increase supplemental rebates in response to lower statutory rebates. These approaches could reduce MCO and PBM reimbursement; it is unlikely they would generate enough savings to offset the loss of best price.

It is not clear what effect changes to best price would have on pharmacy reimbursement. Best price and statutory rebates are separate from the prices paid by Medicaid to pharmacies, which are based on pharmacies’ acquisition costs. However, underlying manufacturer list prices do impact both best price and pharmacy reimbursement. State reimbursement to pharmacies would depend on manufacturer behavior and any price changes, as pharmacy reimbursed is based on the pharmacy’s cost to acquire the drugs.

Pricing Policies Focused on Other Payers

Proposals that would allow the federal government to negotiate the price of prescription drugs on behalf of people enrolled in Medicare Part D drug plans would, in general, increase state Medicaid drug costs due to lower rebate payments but would decrease federal spending overall. Due to rising drug prices and increased federal and beneficiary spending, there has been increased interest in allowing the government to negotiate drug prices for Medicare Part D, which is not allowed under current law. These proposals take varying approaches to how the negotiated prices would impact other programs and payers. Proposals may narrowly focus price negotiation on prices paid by Medicare or extend the price to Medicaid and private insurance. Some proposals also include an additional penalty on drugs with prices rising faster than inflation, similar to the MDRP. A CBO analysis of a proposal to allow the federal government to negotiate drug prices for certain drugs on behalf of Medicare found that Medicaid inflation rebates would decrease and overall Medicaid drug spending would increase. If the negotiated price is extended to Medicaid, state costs could still increase unless there is a provision requiring a drug’s net price to be lower of either the rebate or the negotiated price. CBO also found that that federal spending would decrease significantly due to the large amount saved on Medicare drugs. Medicaid spending would increase as noted above but would be offset by a significant decrease in Medicare spending.

Proposals to import drugs from foreign markets as a way to lower drug prices for consumers have gained attention in recent years but are unlikely to have a substantial effect on Medicaid drug spending. In fall 2020, the Trump Administration issued a final rule and FDA guidance for industry creating new pathways for the safe importation of drugs from Canada and other countries by pharmacists, wholesales, states, and certain entities, subject to specified limitations and safeguards. The law requires importation to result in a significant reduction in drug costs and requires states to submit a plan for approval to the FDA. While some states have developed importation proposals, few have moved forward with implementation due to barriers related to regulation, safety and overall financial impact. In general, while a state may save money through importation, it would likely be through programs other than Medicaid. Due to the high rebate amounts Medicaid receives, unless states could claim rebates on top of lower imported prices, imported prices would likely not be lower than net Medicaid prices. State estimates of current proposals do not anticipate significant savings in Medicaid.

Looking Ahead

Prescription drug policy is likely to remain an issue at both the federal and state levels due to budgetary constraints and the entry of new, high-cost drugs. While federal and state policymakers remain focused on addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic recession due to the pandemic and its impact on state budgets may lead to increased attention on reducing Medicaid prescription drug spending. President Biden has supported policies that would lower prescription drug costs for patients and has prioritized increasing access to affordable health coverage among his early executive actions.42 Congress has already started hearings on legislation to target drug prices and is expected to include such proposals in forthcoming reconciliation bills.

In a narrowly divided Congress, Medicaid prescription drug policies may provide spending offsets for reconciliation bills. In addition to policies directly impacting Medicaid, other drug pricing proposals to negotiate drug prices on behalf of Medicare or other payers would also have implications for Medicaid spending and beneficiary access. State policymakers also continue to be interested in reducing Medicaid drug spending. There may be challenges to implementation of Medicaid drug policy changes due to opposition from stakeholder groups. Proposals that produce federal and state savings due to reduced revenues for other actors such as manufacturers or PBMs, including increased rebates or limiting spread pricing, may face opposition from those groups. In the past, manufacturers and PBMs have challenged laws and other regulatory efforts in court. Assessment of the implications of these proposals for Medicaid, and the actors involved in state Medicaid drug policy, can help understand their potential direct and indirect effects, as well as the politics surrounding them.