Medicaid in an Era of Health & Delivery System Reform: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2014 and 2015

Delivery System Reforms

Use of Managed Care

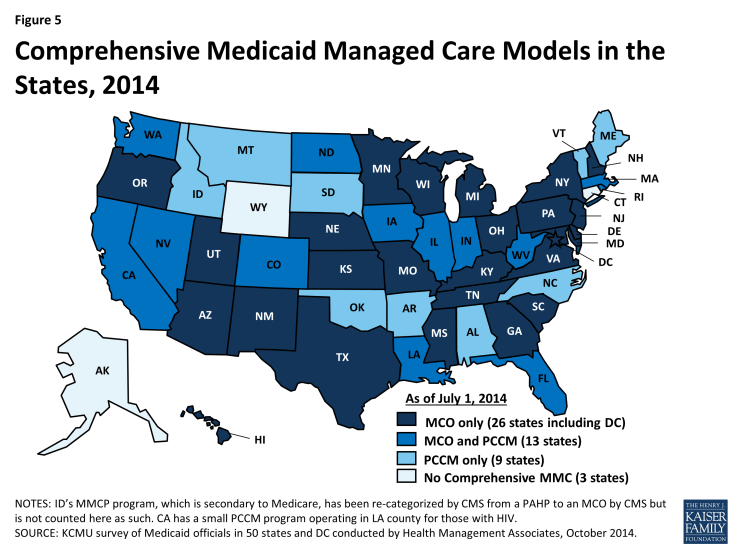

Managed care has become the main delivery system for Medicaid in most states, as Medicaid programs increasingly have turned to managed care as a means to help assure access, improve quality and achieve budget certainty. As of July 2014, all states except three – Alaska, Connecticut and Wyoming – had in place some form of managed care. Across the 48 states with some form of managed care, a total of 39 states including DC had contracts with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs); 22 states administered a Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) program, a managed fee-for-service based system in which beneficiaries are enrolled with a primary care providers who are paid a small fee to provide case management services in addition to primary care. Of the 48 states that operate some form of managed care, a total of 13 states operate both MCOs and a PCCM program while 26 states (including DC) operate MCOs only and nine states operate PCCM programs only.1 (Figure 5) In addition, 20 states contracted with one or more limited-benefit risk-based prepaid health plans to provide behavioral health, dental care, maternity care, non-emergency medical transportation, or other benefits.

The share of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in MCOs, PCCM programs or remaining in fee-for-service varies widely by state. The share enrolled in MCOs, however, has steadily increased as states have expanded their managed care programs to new regions, to new populations and made MCO enrollment mandatory for additional eligibility groups. Among the 39 states (including DC) with MCOs, 16 states reported that over 75 percent of their beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2014.

Notable shifts to increase the use of risk-based managed care during FY 2014 and FY 2015 include two states (New Hampshire and North Dakota) that implemented new risk-based managed care programs. In addition, states like Florida and New Mexico, which have many years of experience with managed care, implemented new expansive statewide managed care programs in FY 2014. Six states (Florida, Indiana, Louisiana, Oregon, South Carolina, and Utah) have ended or plan to end their PCCM programs in FY 2014 or FY 2015 and are transitioning these groups to risk-based managed care organizations. However, not every state has moved in this direction. For example, Vermont currently operates an enhanced-PCCM program and is expanding its use of ACOs as part of its State Innovation Model (SIM) grant.2 Connecticut terminated its MCO contracts in 2012 and now operates its program on a fee-for-service basis using four administrative services only (ASO) entities to manage medical, behavioral health, dental and non-emergency transportation services. The ASOs are accountable for specific performance metrics common to managed care, but the state does not describe its system as managed care.

Risk Based Managed Care Expansions

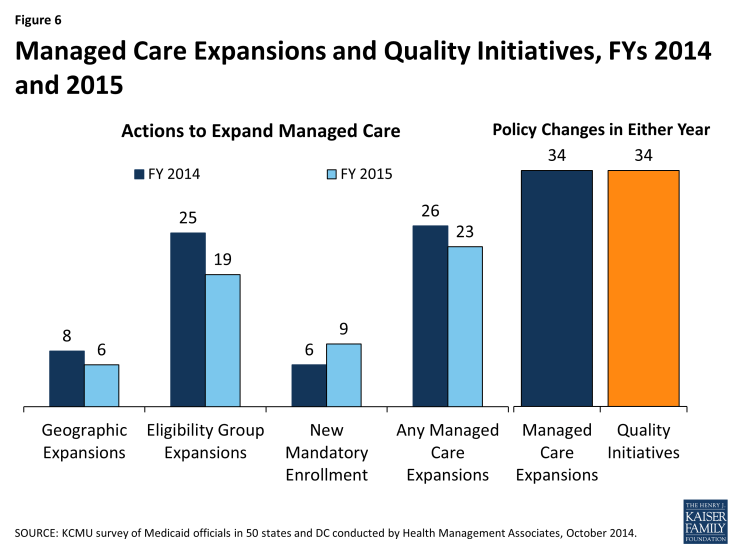

In both FY 2014 and in FY 2015, states continued to take actions to increase enrollment in managed care. Of the 39 states (including DC) with MCOs, a total of 34 states indicated that they made specific policy changes to increase the number of enrollees in MCOs; no states with MCOs took any action designed to restrict MCO enrollment. The most common strategy was to expand voluntary or mandatory enrollment to additional eligibility groups (25 states in FY 2014 and 19 states in FY 2015.) The eligibility group most commonly added to MCOs was the newly eligible adult group in states adopting the ACA Medicaid expansion.

Other commonly noted eligibility groups added to managed care included children (such as those in foster care, adoption subsidy or juvenile justice systems in Florida, Georgia, Nebraska, Texas, and Virginia as well as other groups of children in California, Florida, and Mississippi); those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Ohio, Rhode Island, South Carolina and Virginia); and other elderly individuals or those with disabilities (Indiana, Louisiana, Nebraska, New York, New Jersey, Ohio, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia). In addition, six states made enrollment mandatory for specific eligibility groups in FY 2014, and nine states are doing so in FY 2015. Geographic expansions for MCO service areas occurred in eight states in FY 2014, and in six states in FY 2015. (Figure 6)

Managed Care Quality. As states expand risk-based managed care, they continue to undertake efforts to improve managed care quality and outcomes. New quality improvement initiatives were implemented in 34 states in either FY 2014 or FY 2015. These initiatives include the use of new quality metrics focused on specific conditions (e.g., behavioral health conditions, childhood obesity, hypertension, asthma, and diabetes) and the addition or enhancement of pay-for-performance arrangements, including changes in amounts withheld from monthly capitation payments that are at risk based on each MCO’s performance on specified quality measures. In addition, some states are introducing or expanding public reporting of quality metrics.

Additional information on states that reported managed care changes implemented in FY 2014 or planned for FY 2015 can be found in Table 3.

Primary Care Case Management Programs

Of the 22 states with PCCM programs, six indicated they enacted policies to increase PCCM enrollment in FY 2014 or FY 2015. The state actions include: Arkansas implemented the Delta Pilot Program, an enhanced PCCM. Colorado and Rhode Island are expanding enrollment in their PCCM programs as part of integrated care initiatives for those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid; Rhode Island is also expanding enrollment in their PCCM program for other populations who are elderly or disabled. Iowa is using the PCCM for the expansion of the Wellness Plan, part of their ACA Medicaid expansion waiver. Nevada has launched a new PCCM model targeted to those currently in fee-for-service with co-morbid conditions (about 39,000 members.)

In contrast, eight states (Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Oregon, Utah and South Carolina) have taken actions that decreased enrollment in their PCCM programs.3 Six of these states (Florida, Indiana, Louisiana, Oregon, South Carolina, and Utah) have ended or plan to end their PCCM programs and transition PCCM enrollees to risk-based managed care. In June 2014, Illinois began transitioning 1.5 million PCCM enrollees to “managed care entities” in the five mandatory enrollment regions. In Oklahoma, effective July 2014 individuals with creditable primary coverage are no longer eligible for the SoonerCare Choice PCCM program.

| Managed Care Administrative Policies |

|

MCO Rate-Setting. Federal law requires that state Medicaid programs pay MCOs actuarially sound capitation rates. As the role of capitated managed care has increased, states have paid greater attention to the rate-setting process. States indicated a range of approaches to setting rates for MCOs to achieve actuarially sound rates, often involving a combination of strategies. As of July 2014, the 39 states with MCOs reported using one or more of the following methods in setting actuarially sound rates – administrative-rate setting (29 states), negotiation (12 states), competitive bidding with an actuarially defined range (11 states.) Increasingly, states are contracting with actuarial firms to assist in the rate-setting process as the state administratively sets, bids or negotiates the rates.–

–

Minimum Loss Ratios. For an MCO, the proportion of total per member per month capitation payments that is spent on clinical services and for quality improvement is known as the Medical Loss Ratio (MLR). Thus, the MLR represents the share of dollars that MCOs spend on providing and improving patient care compared to administrative costs, which include executive salaries, overhead, and marketing, and on profits. State insurance regulators commonly set a minimum MLR for commercial health plans, and the ACA mandates a minimum MLR for Medicare Advantage plans and for qualified health plans (QHPs) participating in the health insurance Marketplaces. State Medicaid programs are allowed to set a MLR for Medicaid health plans. As of July 2014, 27 of the 39 states that contracted with comprehensive risk-based MCOs specified a minimum MLR for all or some plans, and 12 states did not have an MLR requirement. Twenty-two of the 27 states with a MLR requirement always applied it and five states applied it on a limited basis (e.g., for the new ACA Medicaid expansion population.) State Medicaid MLRs vary, though most commonly are set at 85 percent. Some states noted that MLRs varied by type of plan or population.–

–

Auto-enrollment. Beneficiaries who are required to enroll in MCOs must be offered a choice of at least two plans. Those who do not select a plan are auto-enrolled in a plan. Of the 39 states with comprehensive risk-based MCOs, all except one required that some or all beneficiaries to enroll in an MCO. (The exception is North Dakota, which has only one health plan.) The proportion of beneficiaries who are auto-enrolled varies widely across states. Five states had auto-enrollment rates of 10 percent or less, while six states auto-enrolled between 70 percent and 80 percent of new MCO enrollees.4 State’s auto-enrollment algorithms also vary, with about half rotating enrollments randomly across plans, and others incorporating a range of factors, including previous connection of the beneficiary or family members to a primary care provider or total plan enrollment. Some states use or plan to use MCO performance on specified quality measures in auto-assigning new enrollees, with higher performing plans receiving some or all auto-enrollments.

|

TABLE 3: MANAGED CARE INITIATIVES TAKEN IN ALL 50 STATES AND DC, FY 2014 and 2015 |

||||||||||

| States | Geographic Expansions | Add Eligibility Groups | New Mandatory Enrollment | Expansions of Managed Care | Quality Initiatives in Managed Care | |||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | Either Year | Either Year | |

| Alabama | ||||||||||

| Alaska | ||||||||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Arkansas | ||||||||||

| California | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Colorado | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Connecticut | ||||||||||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| DC | X | |||||||||

| Florida | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Georgia | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Hawaii | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Idaho | X | |||||||||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Indiana | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Kansas | ||||||||||

| Kentucky | X | X | X | |||||||

| Louisiana | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Maine | ||||||||||

| Maryland | X | |||||||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Mississippi | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Missouri | ||||||||||

| Montana | ||||||||||

| Nebraska | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Nevada | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| New York | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| North Carolina | ||||||||||

| North Dakota | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Oklahoma | ||||||||||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| South Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| South Dakota | ||||||||||

| Tennessee | X | |||||||||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Utah | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Vermont | ||||||||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Washington | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| West Virginia | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Wyoming | ||||||||||

| Totals | 8 | 6 | 25 | 19 | 6 | 9 | 26 | 23 | 34 | 34 |

| NOTES: States were asked if they expanded managed care (comprehensive risk-based managed care) to new regions, new populations, increasing the use of mandatory enrollment or the implementation of new managed care plans. States reported separately if they implemented new quality initiatives in managed care plans as well. SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2014. |

||||||||||

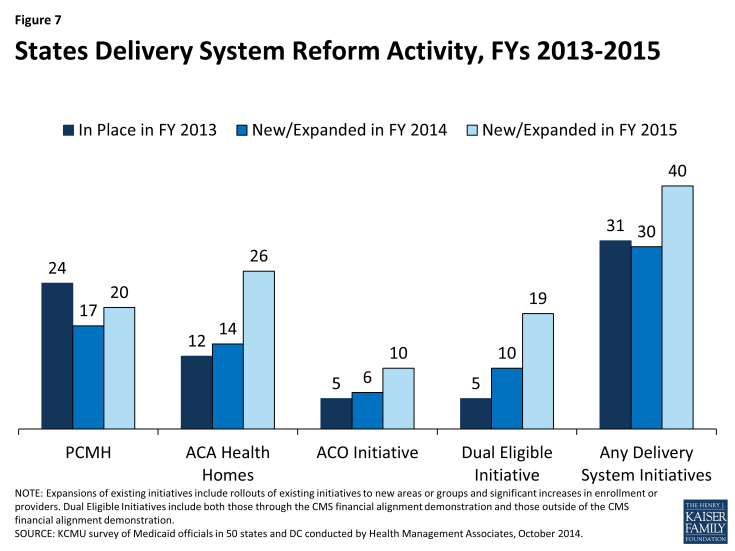

Other Delivery System and Payment Reform

States are increasingly interested in new approaches that hold the promise of improving health outcomes and constraining costs by redesigning the way that care is delivered and paid for. These emerging models which seek to align payment and delivery systems to reward quality and promote more integrated care include initiatives to coordinate physical and behavioral health care, efforts to coordinate acute and long-term care and care management approaches that target persons with multiple chronic conditions. These delivery system and payment reform approaches are sometimes implemented outside of managed care and sometimes within it. This year’s survey asked states which delivery system and payment reform models were in place in FY 2013, or if they had adopted or were enhancing such models in FY 2014 or FY 2015. (Figure 7)

Patient-Centered Medicaid Homes (PCMH). In 2007, four leading physician groups released key principles that define a PCMH: (1) the personal physician leads a team that is collectively responsible for the patient’s ongoing care; (2) the physician is responsible for the whole person in all stages of life; (3) care is coordinated and/or integrated; (4) quality and safety are hallmarks of a medical home; (5) enhanced access to care is available through all systems; and (6) payment appropriately recognizes the added value to the patient. In addition, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) has issued specific standards to be recognized as a PCMH.5 In this survey, 24 states said that PCMHs were “in place” in FY 2013, 17 states reported having adopted or expanding PCMHs in FY 2014 and 20 states indicated plans to do so in FY 2015.

| Patient-Centered Medical Home Initiatives |

|

Connecticut PCMH Initiative: The Connecticut Department of Social Services is investing significant resources to help primary care practices obtain PCMH recognition from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Practices on the “glide path” toward recognition receive technical assistance from Community Health Network of Connecticut, Inc. (CHNCT). Practices that have received recognition are eligible for financial incentives including enhanced fee-for-service payments and retrospective payments for meeting benchmarks on identified quality measures; practices on the glide path receive prorated enhanced fee for service payments based upon their progress on the glide path but are not eligible for quality payments at this time. In this year’s survey, the state reported that approximately one-third of Connecticut’s Medicaid population was assigned to a PCMH with a plan to expand to all enrollees in the future.

–

Virginia’s PCMH Requirement for MCOs: Virginia modified its PCMH requirement in the FY 2014 Medallion II managed care contract (2013-2014) by implementing instead the Medallion Care Systems Partnership. This initiative allows MCOs opportunities to expand and test different methodologies of payment and incentives within the medical home model to advance quality and member outcomes while allowing for small scale pilots of innovative payment reform models.

|

Health Homes. Section 2703 of the ACA provides a new state plan option for Medicaid programs to establish “health homes,” designed to be person-centered systems of care that facilitate access to and coordination of the full array of primary and acute physical health services, behavioral health care, and community-based long-term services and supports, for beneficiaries who have at least two chronic conditions, or one and at risk of a second or a serious and persistent mental health condition. To implement a health home program, a state must obtain CMS approval of a state plan amendment (SPA). A 90 percent federal match rate is available for qualified expenditures for health home services for the first eight quarters of a state’s program.6 The ACA defines health home services to include: comprehensive care management; care coordination and health promotion; transitional care from inpatient to other settings; support for patients and families; referral to community and social support services; and use of Health Information Technology (HIT) to link services.7 In this survey, 12 states said that health homes were “in place” in FY 2013, 14 states reported having adopted or expanded health homes in FY 2014 and 26 states reported plans to do so in FY 2015. Many states noted that they were focusing their health home programs on populations with behavioral health conditions as well as populations with multiple chronic conditions.

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). An ACO is a provider-led group of health care providers that agree to share responsibility for the delivery of care to and health outcomes of a defined group of people and the cost of their care. The organizational structure of ACOs varies, but all ACOs include primary and specialty care physicians and at least one hospital. Providers in an ACO are expected to coordinate care for their shared patients to enhance quality and efficiency, and the ACO as an entity is accountable for that care. An ACO that meets quality performance standards that have been set by the payer and achieves savings relative to a benchmark can share savings with the payer and distribute them among its providers. Some states that are pursuing ACOs for Medicaid beneficiaries are building on existing care delivery programs (e.g., PCCM, medical homes, MCOs) which already involve some degree of coordination among providers and may have some of the infrastructure (e.g., electronic medical records) necessary to support coordination among ACO providers. States use different terms for their Medicaid ACO initiatives, such as Coordinated Care Organizations (CCOs) in Oregon and Accountable Care Collaboratives (ACCs) in Colorado.8

In this survey, five states reported that ACOs were “in place” in FY 2013, six states reported adopting or expanding ACOs in FY 2014 and ten states reported such activity in FY 2015. Some states have sought or are seeking to reorganize some or all of their Medicaid delivery system into ACOs (Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Oregon, Utah, and Vermont,) while ACO efforts in other states have been more provider-driven (California, New Jersey, and South Carolina.) Also, a number of states noted that their ACO initiatives are part of larger State Innovation Model (SIM) grants that involve multiple payers.

Care Coordination and Integration of Care for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries. Coordinating care for those dually-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (dual eligible beneficiaries) is a significant issue for Medicaid programs. Dual eligible beneficiaries comprise just 14 percent of Medicaid enrollees but accounted for 36 percent of Medicaid spending in 2010. For Medicare, dual eligible beneficiaries accounted for 20 percent of all enrollees but 33 percent of all spending in 2009.9 About 65 percent of all spending for dual eligible individuals is for long-term services and supports, covered largely by Medicaid, and about 25 percent is for acute care services, primarily covered by Medicare.10 These individuals tend to have significant health needs, a high prevalence of chronic conditions and substantial use of long-term services and supports.

Prior to the ACA, coordination of care for individuals with dual enrollment in Medicaid and Medicare had been difficult to pursue for states in part because of misalignment between Medicare and Medicaid laws. In addition, when states did develop approaches to better coordinate care, any resulting savings from improvements in acute care (such as reduced inpatient admissions, re-admissions and emergency room visits) most often accrued to Medicare and were not shared with state Medicaid programs. Under Section 2602 of the ACA, CMS established the Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office (MMCO) and initiated financial alignment demonstrations with interested states seeking to coordinate and improve care and control costs for those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

In this survey, five states indicated that initiatives to coordinate care for dual eligible beneficiaries were in place in FY 2013; all of these initiatives were outside the CMS financial alignment demonstration and centered on enrolling this population in comprehensive MCOs or in managed long-term care plans. In FY 2014, ten states noted new or expanded initiatives for dual eligible beneficiaries, five of which related to the implementation of a financial alignment demonstration. In FY 2015, 19 states noted plans to implement an initiative focused on this population, of which 13 planned to implement a financial alignment demonstration.11 Initiatives outside of the financial alignment demonstrations included alignment of Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plans for dual eligible beneficiaries (D-SNPs) with Medicaid MCOs and enrollment of dual eligible beneficiaries in comprehensive Medicaid MCOs (for acute care services) or managed long-term care.

Additional information on states that reported delivery system and payment reform initiatives implemented in FY 2014 or planned for FY 2015 can be found in Table 4.

| Other Emerging Delivery System and Payment Reforms |

|

This year’s survey asked states about two emerging delivery system and payment reform initiatives: Episode of Care Payments and DSRIP programs, described below. Aside from these two initiatives, states also commonly mentioned payment reforms that focused on reducing preventable admissions and readmissions, hospital acquired conditions, and elective early deliveries.

–

Episode-of-Care Initiative. Unlike fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement where providers are paid separately for each service, or capitation where a health plan receives a per member per month payment intended to cover the costs for all covered services, an episode-of-care payment is linked to the care that a patient receives in the course of treatment for a specific illness, condition or medical event (e.g., knee replacement, pregnancy and delivery, or heart attack). Episode-based payments create a financial incentive for physicians, hospitals and other providers to work together to improve patient care related to an episode of illness or a chronic condition. In this survey, two states (Arkansas and Tennessee) said that an episode-of-care initiative was in place in FY 2013; both of these states indicated that they had adopted or expanded their episode-of-care initiative in FY 2014 while seven states (Arizona, Arkansas, New Mexico, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Tennessee) planned to implement or expand their episode-of-care initiative in FY 2015. A number of these states noted that episodes of care were part of their State Innovation Model (SIM) grant proposals.–

–

Arkansas, for example, reported that its Payment Improvement Program (PIP) is designed to promote efficiency, economy and quality of care by rewarding high-quality care and outcomes, encouraging clinical effectiveness, promoting early intervention and coordination to reduce complications and associated costs, and, when provider referrals are necessary, encouraging referral to efficient and economic providers who furnish high-quality care. The PIP uses episode-based data to evaluate the quality, efficiency and economy of care delivered in the course of an episode and to apply payment incentives. The PIP is separate from, and does not alter, current methods for reimbursement. Instead, at the conclusion of each performance period, the average cost of the episode for a “Principal Accountable Provider” (PAP) is calculated and evaluated against predetermined cost thresholds to determine whether there will be risk or gain sharing payments for the PAP.

–

Hospital Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Program. Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment or DSRIP programs are another piece of the dynamic and evolving Medicaid delivery system reform landscape. DSRIP initiatives are part of broader Section 1115 waiver programs and provide states with significant funding that can be used to support hospitals and other providers in changing how they provide care to Medicaid beneficiaries. Originally, DSRIP initiatives were more narrowly focused on funding for safety-net hospitals and often grew out of negotiations between states and HHS over the appropriate way to finance hospital care. Now, however, they increasingly are being used to promote a far more sweeping set of payment and delivery system reforms. The first DSRIP initiatives were approved and implemented in California and Texas in 2010 and 2011, followed by New Jersey, Kansas and Massachusetts in 2012 and 2013 and most recently New York which was approved in 2014 and will be implemented in 2015. Under DSRIP initiatives, funds to providers are tied to meeting performance metrics. In this year’s survey, nine states (California, Illinois, Kansas, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, and Texas) indicated that they plan to implement or expand DSRIP programs in FY 2015.

|

TABLE 4: DELIVERY SYSTEM INITIATIVES IN PLACE IN FY 2013 AND ACTIONS TAKEN IN FY 2014 AND FY 2015 IN ALL 50 STATES AND DC |

|||||||||||||||

| States | Patient Centered Medical Homes | Health Homes | Accountable Care Organizations | Initiatives for Dually-Eligible Individuals | Delivery System Initiatives | ||||||||||

| In Place 2013 | New or Expansions in: | In Place 2013 | New or Expansions in: | In Place 2013 | New or Expansions in: | In Place 2013 | New or Expansions in: | In Place 2013 | New or Expansions in: | ||||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | ||||||

| Alabama | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Alaska | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| California | X | X | X* | X* | X | X | |||||||||

| Colorado | X | X | X* | X | X | ||||||||||

| Connecticut | X | X | X | X | X* | X | X | X | |||||||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| DC | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Florida | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Georgia | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Hawaii | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Idaho | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | X* | X* | X | X | |||||||

| Indiana | |||||||||||||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Kansas | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Kentucky | |||||||||||||||

| Louisiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Maine | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Maryland | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X* | X* | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Michigan | X | X | X* | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Mississippi | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Missouri | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Montana | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Nebraska | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Nevada | |||||||||||||||

| New Hampshire | |||||||||||||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| New York | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* | X | X | X | |||||

| North Carolina | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| North Dakota | |||||||||||||||

| Ohio | X | X | X* | X | X | ||||||||||

| Oklahoma | X | X | X | X* | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X* | X | X | X | |||

| South Carolina | X | X | X | X | X* | X | X | X | |||||||

| South Dakota | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Texas | X | X | X* | X | X | ||||||||||

| Utah | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Vermont | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | X* | X* | X | X | X | ||||||

| Washington | X | X | X* | X | X | ||||||||||

| West Virginia | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Wyoming | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Totals | 24 | 17 | 20 | 12 | 14 | 26 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 19 | 31 | 30 | 40 |

| NOTES: Expansions of existing initiatives include rollouts of existing initiatives to new areas or groups and significant increases in enrollment or providers. Health Homes: All states noted as either in place in FY 2013 or implementing new/expanded initiatives in FY 2014 have at least one approved SPA except for Michigan and Maine (both states have state legislation in place.) Dually-Eligible Initiatives: X* = state is pursuing the financial alignment demonstrations; all but three states (CT, OK, and RI) had a signed MOU with CMS to implement a financial alignment demonstration in place at the time of the survey while the others had proposals pending. Minnesota has a signed MOU with CMS for an administrative alignment demonstration. CA (FYs 2014 and 2015) and NY (FY 2015) reported other initiatives outside of the demonstration.SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2014. |

|||||||||||||||

Balancing Institutional and Community Based Long-term services and supports

Medicaid is the nation’s primary payer for long-term services and supports (LTSS) covering a continuum of services ranging from home and community-based services (HCBS) that allow persons to live independently in their own homes or in the community, to institutional care provided in nursing facilities and intermediate care facilities for individuals with intellectual disabilities (ICF-ID). LTSS consumes nearly one-third of total Medicaid spending and therefore remain an important focus for state policymakers.12 This year’s survey shows that the long-term trend of expanding HCBS has accelerated with states employing a variety of tools and strategies including traditional Section 1915(c) HCBS waivers, PACE programs13, and managed LTSS.

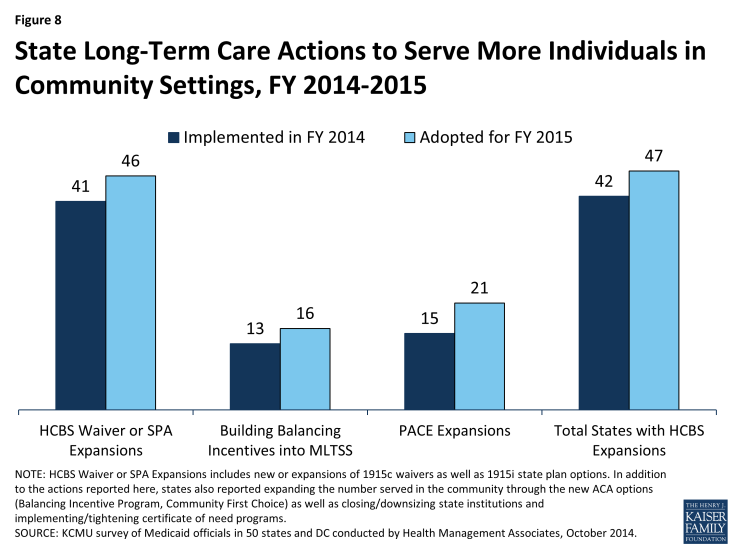

The number of states taking actions to expand the number of persons served in community settings increased substantially in FY 2014 (42 states) and again in FY2015 (47 states) compared to earlier years (26 states in FY 2012 and 33 in FY 2013.) While most states reported using Section 1915(c) waiver or Section 1915(i) state plan authority to expand HCBS, a significant number of states (13 in FY 2014 and 16 in FY 2015) reported that the incentives built into their managed care programs were expected to increase the availability of HCBS. Also, 15 states in FY 2014 and 21 states in FY 2015 reported implementing or expanding PACE programs.14 (Figure 8) A number of states (10 states in FY 2014; 14 in FY 2015) reported closing or downsizing institutions that led to more community placements. States also reported increased take up of the ACA options to expand community-based LTSS (discussed below.)

Figure 8: State Long-Term Care Actions to Serve More Individuals in Community Settings, FY 2014-2015

Several states reported a number of other rebalancing initiatives. Connecticut reported implementing a first of its kind balancing bond funding program to help the state’s nursing home industry diversify services to meet the changing needs of older adults and other people with disabilities. Governor Malloy announced the first round of awards (a total of $9 million for seven proposals) in March 2014 as part of the state’s strategic plan to rebalance its LTSS system.15 Georgia reported that it is working to design a quality incentive payment program that would incent shifts toward person-centered care in some HCBS waivers. Hawaii reported implementing an LTSS program in FY 2014 that allows those who meet “at-risk” criteria to receive several home and community-based services. Several states also noted the implementation of conflict-free case management and single points of entry.16 No state reported new HCBS restrictions or limitations in FY 2014 or FY 2015.17 Two states reported other policy changes affecting institutional LTSS. Indiana liberalized its Certificate of Need statute effective in FY 2015 and Rhode Island reported that in FY 2014 it accepted applications to authorize new nursing home beds as “Resident-directed homes,” which are defined as nursing facilities that include programs and physical structures that adhere to the “Eden Alternative™”, “Green House™”, “Small House”, or any other resident-directed operational model where residents and their family members participate in making decisions that may be directly influenced by residents’ individual preferences and that involve the day-to-day activities and operations of the nursing facility.

Long-Term Services and Supports Options in the ACA

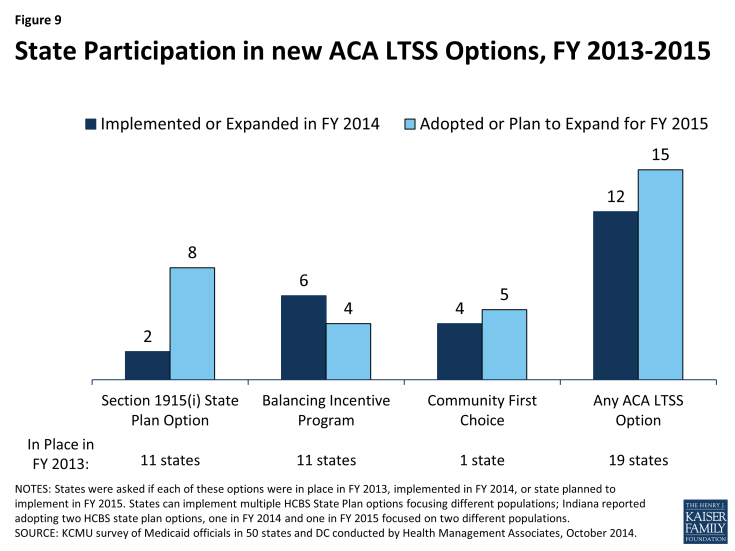

The ACA created and expanded several LTSS-related options intended to promote LTSS rebalancing. Nineteen states reported having at least one of the options discussed below in place in FY 2013; an additional 12 states reported implementing at least one of the these options in FY 2014 and 15 reported plans to do so in FY 2015. (Figure 9) State utilization of each of these options is discussed below.

Section 1915(i) HCBS State Plan Option. This option allows states to offer HCBS through a Medicaid state plan amendment rather than through a Section 1915(c) waiver. As a result of changes made in the ACA, income eligibility for this option was extended up to 300 percent of the maximum SSI federal benefit rate and states were permitted to target benefits to specific populations and offer the same range of HCBS under Section 1915(i) as are available under Section 1915(c) waivers. Unlike Section 1915(c) waivers, however, states are not permitted to cap enrollment or maintain a waiting list and, if offered, the benefit must be available statewide. If enrollment exceeds the state’s projections, the state may tighten their Section 1915(i) needs-based eligibility criteria, subject to advance notice and grandfathering of existing beneficiaries. Eleven states reported having an HCBS state plan option in place in FY 2013. Two states (Indiana and Mississippi) reported implementing in FY 2014, seven states (District of Columbia, Delaware, Maryland, Minnesota, Texas, South Carolina and Washington) reported plans to implement in FY 2015, and one state (Indiana) reported plans to implement a second HCBS state plan option amendment in FY 2015.

Balancing Incentive Program (BIP). Beginning in October 2011, BIP makes enhanced Medicaid matching funds available to certain states that meet requirements for expanding the share of LTSS spending for HCBS (and reducing the share of LTSS spending for institutional services). Funding is available through September 2015.18 To qualify, states must have devoted less than 50 percent of their LTSS spending to HCBS in FFY 2009, develop a “no wrong door/single entry point” system for all LTSS, create conflict-free case management services, and develop core standardized assessment instruments to determine eligibility for non-institutionally based LTSS. In this year’s survey, 11 states reported having BIP in place in FY 2013, six states reported implementing in FY 2014 (Connecticut, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Maine, Nevada, and New York), and four states reported plans to implement in FY 2015 (Nebraska, New Hampshire, Ohio and Pennsylvania.19)

Community First Choice (CFC) State Plan Option. Beginning in October 2011, states electing this state plan option to provide Medicaid-funded home and community-based attendant services and supports will receive an FMAP increase of six percentage points for CFC services. However, the final federal rule implementing this option was not released by CMS until May 201220, inhibiting state take-up of this option prior to FY 2013. In this year’s survey, California was the only state to report having CFC in place in FY 2013.21 Four states reported implementing this option in FY 2014 (Maryland, Minnesota, Montana and Oregon) and five states reported plans to implement in FY 2015 (Arkansas, Connecticut, New York, Texas and Washington).

Additional information on LTSS expansions implemented in FY 2014 or planned for FY 2015 can be found in Tables 5 and 6.

| New Rules Impacting HCBS Services |

|

In this year’s survey, states were asked to comment on the top issues, concerns or opportunities related to two recently released rules affecting HCBS services.

–

HCBS Rule. In January 2014, CMS issued a new HCBS regulation (the “HCBS Rule”) making a number of significant program changes including defining person-centered planning requirements for persons in HCBS settings, providing the option to combine multiple target populations into one § 1915(c) waiver, and establishing a five-year renewal cycle for § 1915(c) waivers. Perhaps most significant, however, are new requirements that define the qualities of settings that are eligible for Medicaid reimbursement under § 1915(c) waivers, the § 1915(i) HCBS State Plan Option and the Community First Choice Option.22 Almost half of the states cited concerns with the new HCBS settings requirements. Concerns were raised that the new settings requirement was “not sensitive to different needs of various LTSS populations (e.g., beneficiaries who have an intellectual disability, Alzheimer’s or other dementia or behavior issues)” and that the “emphasis on integration discounts to some extent personal choices (i.e., the choice to attend a Senior Day Center.)” A number of states expressed concerns with Transition Plan requirements, particularly the limited time provided to complete the planning process. Additional concerns were raised about the difficulty that providers, particularly those in rural areas, might face in complying with the new rules (both in terms of cost and physical plant changes). One state noted that complying with the settings requirements in assisted living and adult family care home settings was their top concern. On the other hand, a number of states noted that the new ability to consolidate multiple waivers into one combined § 1915(c) waiver and to apply common standards across waivers would be helpful. One state commented that the new rule would help the state comply with aspects of the Olmstead decision.23

–

Fair Labor Standards Act Extension to Home Care Workers. In a final rule published on October 1, 2013 (the “DOL Rule”), the U.S. Department of Labor revised the long-standing Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) exemptions for “companionship services” and “live-in domestic service workers.” As a result, many direct care workers (including home health aides and personal care assistants) providing essential home care assistance to persons with disabilities and older adults will become entitled to receive the FLSA minimum wage and overtime pay protections beginning in January 2015 with significant implications for many Medicaid HCBS programs. Home care agencies as well as states could be held responsible for complying with the FLSA minimum wage and overtime provisions depending on who is considered to be the home care worker’s employer. In this year’s survey, 20 states indicated that they were still assessing the impact of the rule. Eight states believed the rule would have only a minimal impact on their HCBS programs; some of these states had already applied state minimum wage and other labor requirements to their home health agencies and personal care workers.

–

Many states cited a number of concerns with the rule; most commonly noted was the negative state fiscal impact the rule was estimated to have. Oregon, for example, said that due to its robust in-home program, the fiscal impact during the state’s next budget cycle was estimated at $242 million ($74.2 million in state funds). California indicated it had the nation’s largest self-directed home care program and that in response to the rule, $172 million in state funding was added to the budget for FY 2015 and that $354.4 million annually would be needed on an ongoing basis. Other challenges of administering the rule raised by states included the need to track travel time and hours worked for multiple clients. Several states were concerned that individuals would experience service reductions or fragmented care due to the need for the state to cap service hours or otherwise reduce consumer-directed programs.

–

On October 7, the Department of Labor released a statement saying “[the] department decided to adopt a time-limited non-enforcement policy…[F]rom January 1, 2015 to June 30, 2015, the department will not bring enforcement actions against any employer who fails to comply with a [FLSA] obligation newly imposed by the rule….[F]rom July 1, 2015 to December 31, 2015, the department will exercise its discretion in determining whether to bring enforcement actions, giving strong consideration to the extent to which states and other entities have made good faith efforts to bring their home care programs into FLSA compliance.”

|

TABLE 5: LONG TERM CARE EXPANSIONS IN ALL 50 STATES AND DC, FY 2014 and 2015 |

||||||||

| States | Long Term Care Expansions | |||||||

| HCBS Expansions | Buidling Balancing Incentives in MLTSS | PACE Expansions | Total | |||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Alabama | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Alaska | ||||||||

| Arizona | ||||||||

| Arkansas | ||||||||

| California | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Colorado | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Connecticut | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| DC | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Florida | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Georgia | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Hawaii | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Idaho | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Indiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Iowa | X | X | X | |||||

| Kansas | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Kentucky | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Louisiana | X | X | ||||||

| Maine | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Maryland | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Mississippi | X | X | ||||||

| Missouri | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Montana | X | X | ||||||

| Nebraska | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Nevada | X | X | X | X | ||||

| New Hampshire | ||||||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| New York | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| North Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| North Dakota | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Ohio | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Oklahoma | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| South Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| South Dakota | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Utah | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Vermont | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Washington | X | X | X | X | ||||

| West Virginia | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Wyoming | X | X | X | |||||

| Totals | 41 | 46 | 13 | 16 | 15 | 21 | 42 | 47 |

| NOTES: HCBS Waiver or SPA Expansions includes new or expansions of 1915c waivers as well as 1915i state plan options. Minnesota reported covering more individuals under their Community First Services and Supports Program which operates through a Section 1115 waiver; this change is counted under HCBS waiver or SPA expansions. In addition to the actions reported here, states also reported expanding the number served in the community through the new ACA options (Balancing Incentive Program, Community First Choice) as well as closing/downsizing state institutions and implementing/tightening certificate of need programs. SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2014. |

||||||||

TABLE 6: STATE ADOPTION OF ACA LTSS OPTIONS IN ALL 50 STATES AND DC, FY 2013 – 2015 |

||||||||||||

| 1915(i) State Plan Option | Balancing Incentives Program | Community First Choice | Any ACA LTC Option | |||||||||

| In Place | New in: | In Place | New in: | In Place | New in: | In Place | New in: | |||||

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Alabama | ||||||||||||

| Alaska | ||||||||||||

| Arizona | ||||||||||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| California | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Colorado | ||||||||||||

| Connecticut | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Delaware | X | X | ||||||||||

| DC | X | X | ||||||||||

| Florida | X | X | ||||||||||

| Georgia | X | X | ||||||||||

| Hawaii | ||||||||||||

| Idaho | X | X | ||||||||||

| Illinois | X | X | ||||||||||

| Indiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Kansas | ||||||||||||

| Kentucky | X | X | ||||||||||

| Louisiana | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Maine | X | X | ||||||||||

| Maryland | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | ||||||||||

| Michigan | ||||||||||||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Mississippi | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Missouri | X | X | ||||||||||

| Montana | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Nebraska | X | X | ||||||||||

| Nevada | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | ||||||||||

| New Jersey | X | X | ||||||||||

| New Mexico | ||||||||||||

| New York | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| North Carolina | ||||||||||||

| North Dakota | ||||||||||||

| Ohio | X | X | ||||||||||

| Oklahoma | ||||||||||||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | ||||||||||

| Rhode Island | ||||||||||||

| South Carolina | X | X | ||||||||||

| South Dakota | ||||||||||||

| Tennessee | ||||||||||||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Utah | ||||||||||||

| Vermont | ||||||||||||

| Virginia | ||||||||||||

| Washington | X | X | X | |||||||||

| West Virginia | ||||||||||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | ||||||||||

| Wyoming | ||||||||||||

| Totals | 11 | 2 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 19 | 12 | 15 |

| NOTES: States were asked if each of these options were in place in FY 2013, implemented in FY 2014, or state planned to implement in FY 2015. States can implement multiple HCBS State Plan options focusing different populations; Indiana reported adopting two HCBS state plan options, one in FY 2014 and one in FY 2015 focused on two different populations.SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2014. | ||||||||||||