Beyond the Numbers: Access to Reproductive Health Care for Low-Income Women in Five Communities

Tulare County, CA

KFF: Usha Ranji, Michelle Long, and Alina Salganicoff

Health Management Associates: Carrie Rosenzweig and Sharon Silow-Carroll

Introduction

The state of California has a wide range of legal protections for reproductive health care access and coverage. Its decision to expand its Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) greatly broadened health insurance coverage for its low-income populations, and the state’s Family PACT program ensures coverage for family planning services to uninsured women up to 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL). California requires that Medicaid and private insurance plans cover abortion. However, these coverage protections have not guaranteed equal access in all parts of the state. Tulare County sits in the Central Valley, the heart of the agricultural region of California. The majority of its population is concentrated in a few small cities in an otherwise sparsely populated county. The area is more politically and socially conservative than many parts of the state. As one of the poorest counties in California, Medicaid expansion has been a significant source of coverage for low-income individuals living there. Still, the area is federally designated as medically underserved and as a health professional shortage area, and residents can face significant barriers in accessing basic health care and family planning services. Tulare County’s rates of some sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and teen pregnancy are much higher than the state average. Tulare County’s large migrant worker, immigrant, and Latinx populations, as well as individuals who identify as LGBTQ, face heightened barriers to care.

The state of California has a wide range of legal protections for reproductive health care access and coverage. Its decision to expand its Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) greatly broadened health insurance coverage for its low-income populations, and the state’s Family PACT program ensures coverage for family planning services to uninsured women up to 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL). California requires that Medicaid and private insurance plans cover abortion. However, these coverage protections have not guaranteed equal access in all parts of the state. Tulare County sits in the Central Valley, the heart of the agricultural region of California. The majority of its population is concentrated in a few small cities in an otherwise sparsely populated county. The area is more politically and socially conservative than many parts of the state. As one of the poorest counties in California, Medicaid expansion has been a significant source of coverage for low-income individuals living there. Still, the area is federally designated as medically underserved and as a health professional shortage area, and residents can face significant barriers in accessing basic health care and family planning services. Tulare County’s rates of some sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and teen pregnancy are much higher than the state average. Tulare County’s large migrant worker, immigrant, and Latinx populations, as well as individuals who identify as LGBTQ, face heightened barriers to care.

This case study examines access to reproductive health services for low-income women in Tulare County, California. It is based on semi-structured interviews conducted in March and April 2019 by staff of KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) with local safety net clinicians and clinic directors, social service and community-based organizations, researchers, and health care advocates, as well as a focus group with Spanish-speaking, low-income women living in the community. Interviewees were asked about a wide range of topics that shape access to and use of reproductive health care services in their community, including availability of family planning and maternity services, provider supply and distribution, scope of sex education, abortion restrictions, and the impact of state and federal health financing and coverage policies locally. An Executive Summary and detailed project methodology are available at https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/report/beyond-the-numbers-access-to-reproductive-health-care-for-low-income-women-in-five-communities.

| Key Findings from Case Study Interviews and Focus Groups of Low-Income Women |

|

Medicaid Coverage

Many Tulare County residents live in extreme poverty, and there are a significant number of immigrants, including many monolingual Spanish speakers. These communities face serious barriers to health care despite the availability of expanded coverage under Medicaid and the state family planning program.

| Table 1: California Medicaid Eligibility Policies and Income Limits | |

| Medicaid Expansion | Yes |

| Medicaid Family Planning Program Eligibility | 200% FPL |

| Medicaid Income Eligibility for Adults Without Children, 2019 | 138% FPL |

| Medicaid Income Eligibility for Pregnant Women, 2019 | 322% FPL |

| Medicaid Income Eligibility for Parents, 2019 | 138% FPL |

| NOTE: The federal poverty level for a family of three in 2019 is $21,330. SOURCE: KFF State Health Facts, Medicaid and CHIP Indicators. |

|

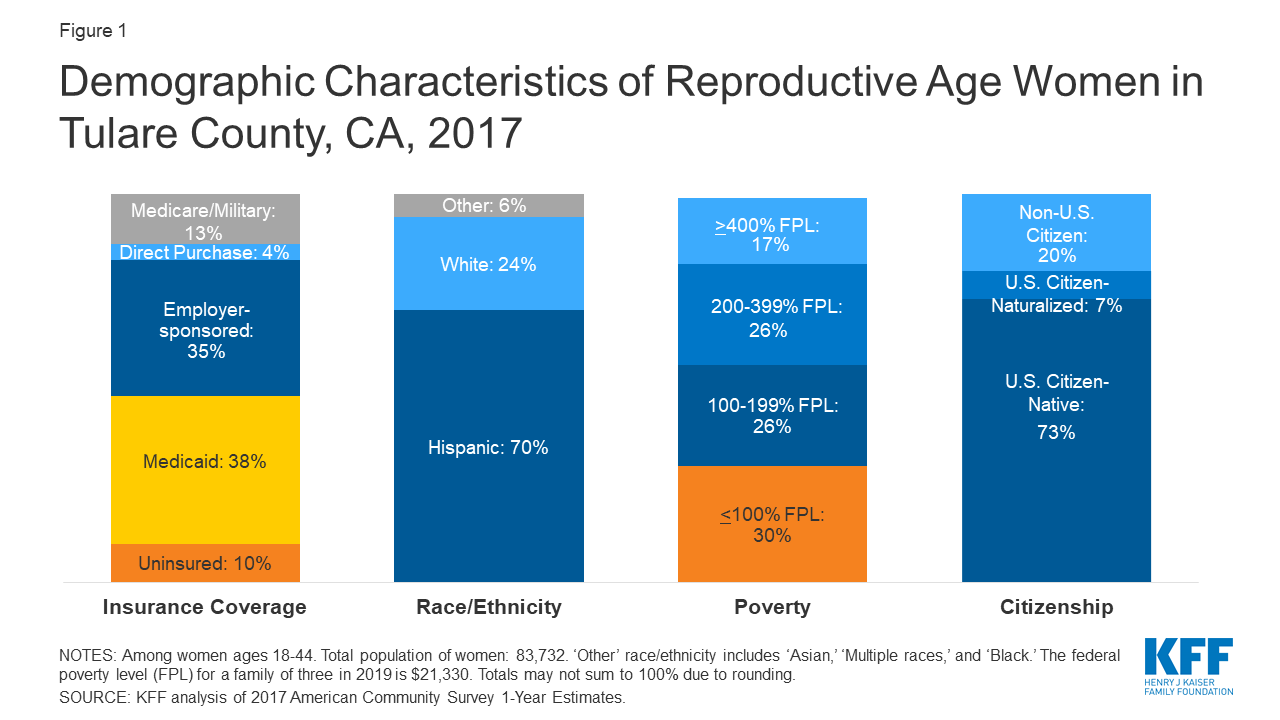

California’s decision to expand Medi-Cal provided broad coverage to many who were formerly uninsured and drastically reduced the uninsured rates in the state; however, gaps remain for undocumented individuals. The 2013 Medicaid expansion greatly increased coverage in Tulare County. California’s Medicaid program covers parents with incomes under 138% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), and pregnant women up to 322% FPL under the CHIP “unborn child” option.1 California also extends coverage for family planning services to men and women with incomes below 200% FPL through the Family PACT program, which serves as a major revenue source for clinics serving low-income women across the state. However, several women who participated in the focus group, many of whom were previously undocumented, had not heard of the Family PACT program or did not know that they were eligible for its family planning services. Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) in the area reported that they still see a significant number of patients who are uninsured, usually because of documentation reasons. Among women of reproductive age in Tulare County, approximately seven in ten are Latinx and nearly three in ten are foreign-born (Figure 1). Agriculture is the dominant industry in the region, and the county is home to many farm workers and their families. In June 2019, following the site visit, California became the first state to expand full Medi-Cal benefits with state-only funding to low-income, undocumented adults ages 19-25, expected to take effect in 2020.

Provider Distribution

Tulare County’s large area and lack of public transit make it difficult for women to travel to larger towns for health care appointments. While prenatal and contraceptive care are generally accessible in the county, there is a significant shortage of providers of specialty care and even fewer specialists who accept Medicaid.

Tulare County is an expansive county, about the size of Connecticut, with a sizable rural footprint. There are provider shortages in the more rural areas, and services are concentrated in the larger towns. Outlying areas that are farther away from the population centers in Tulare and Visalia have limited or no public transportation options, which reduces access to health care services for residents without cars. Interviewees also reported difficulty recruiting doctors to live and work in the area. Some FQHCs are trying to improve access and expand their presence throughout the county using mobile units, satellite clinics, and a transportation fleet to bring patients to and from their appointments free of charge. However, they acknowledge it is not financially viable to build clinics in outlying communities with 100 people (or fewer), and some interviewees suggested that patients do not always know about available transportation services; for example, Medicaid covers transportation to medical appointments in certain cases. The combination of geographic distance, limited public transportation and knowledge of available services means that it is difficult for people in some outlying communities to obtain care.

Focus group participants reported that prenatal care is readily accessible, though their provider choices are limited. Some interviewees expressed that while there may be enough Ob-Gyns in the county, they are not evenly distributed, and the range of Ob-Gyns does not fully meet patient preferences. For example, interviewees and women in the focus group said that the field is male-dominated in the area, and the few doulas and midwives in the county, who are generally female, are overbooked. FQHCs suggested telehealth could help, but they do not currently use this technology for reproductive health or obstetrics. One interviewee commented that there are limited obstetric specialists, so providers refer patients to nearby hospitals for specialty care; however, recent hospital closures have reduced the number of obstetric departments in the area. As in other communities, many private providers do not accept Medi-Cal due to the state’s low reimbursement rates, which are among the lowest in the nation. One interviewee suggested this creates a “two-track system” in which patients with Medicaid are limited to a smaller number of providers.

| Initiative: Expanding access to culturally competent perinatal care |

| Family HealthCare Network, a large, multi-site FQHC in Tulare County, is a participating provider in the Comprehensive Perinatal Services Program (CPSP). They strive to provide culturally competent services to pregnant women enrolled in Medi-Cal in order to decrease the incidence of low-birthweight babies and improve birth outcomes. Funded by the Title V Maternal and Child Health Block Grant Program, CPSP offers enhanced services including nutrition, psychosocial and health education from conception through 60 days postpartum. |

Women have access to a variety of contraceptive providers, but limitations remain. Women can get same-day contraception from several FQHCs and a Planned Parenthood clinic in the area. The two county public health clinics also offer some contraceptive services. Planned Parenthood in Visalia was identified by multiple interviewees as the most comprehensive, and the only specialized provider of contraception; however, Planned Parenthood is only open three days a week with limited hours. These limitations are particularly exacerbated for residents in the outlying areas of the county who have to travel farther to get care. In California, pharmacists can prescribe and provide some hormonal contraception (oral contraceptive pills, the patch, injection, and the ring) directly to women. One interviewee noted that pharmacies are one of the “cornerstones” of access in the community, but that not many pharmacists in the area participate in the program due to personal beliefs. A local social justice organization that conducts “secret shopping” at local pharmacies to identify barriers to obtaining emergency contraception (EC) has greatly improved access. Cost is still a barrier since EC costs $40-60 without a prescription, but it is also available at local FQHCs and Planned Parenthood on a sliding fee scale.

Mental health needs are not being met within the community. Although many focus group participants had suffered from anxiety and depression, they said that doctors only talk to them about it when they are pregnant. Long wait times for appointments at the limited number of mental health providers in the county is a barrier to care. One interviewee reported there is a two-month wait for a pediatric mental health assessment, though the victims’ services provider can offer counseling for children who have been exposed to violence, or experienced neglect, endangerment, or abuse within about two weeks. Adults can get mental health services in Visalia or Kingsview, but these services reportedly focus on severe mental health diagnoses only.

Sex Education and STIs

The availability of sex education in the schools is limited in the region despite robust state requirements. Nurses play a large role in educating their patients about sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Sex education is not consistently taught across the 45 school districts in the county despite a state mandate that schools provide comprehensive sex education. Interviewees report a lag between the state’s passage of legislation and implementation on the ground due to limited resources and lax oversight. The local school board is also resistant to sex education, tied to strong conservative and anti-abortion Roman Catholic influences in the community. Tulare-Kings Right to Life has historically provided abstinence-only sex education in the schools; many interviewee and focus group participants noted this limited curriculum does not offer young people the information they need to make fully informed decisions about their health. Some also noted that as sex education comes into compliance with state law, some parents are choosing to opt their children out of the more comprehensive programs. One interviewee described backlash when an advocacy organization handed out condoms at a high school prom and performed rapid HIV testing at a homelessness event.

“We are a close community that doesn’t know about contraceptives because that is not a topic we talk about at home.” –Focus group participant

Health educators and nurses at local clinics play an important role in educating women about STIs and their contraceptive options. FQHC nurses reported that their patients are uneducated about their sexual health and are often surprised when they learn about STI symptoms and risk factors. However, providers feel limited in their reach because they are only able to educate people who walk into their clinic. On the other hand, focus group participants did not think that providers sufficiently discuss STIs with them. They reported receiving pamphlets but stated they would prefer in-person counseling with reader-friendly guides.

“We [nurses] are a big support to our providers. We do most of the counseling before they see the physician, so the patients can make a decision and get the method they want once they see the doctor.”

–Gabriela Beltran, Title X Patient Care Coordinator, Altura Centers for Health

| Initiative: Primary care and sexual health integration |

| Altura Centers for Health, an FQHC and the Title X provider in the region, works to integrate STI testing and treatment services with primary care. Patient Care Teams, comprised of the provider, Medical Assistant and Patient Care Coordinator, have been successful in integrating screening services at the FQHC’s primary care offices with the goal of testing every sexually active patient once a year. The Patient Care Teams have been taught how to ask patients if they would like to be tested for STIs and how to describe how to collect a urine sample in a patient-centered manner.

Altura Centers for Health also has trained Community Health Educators who conduct health screenings at agricultural sites geared toward the large population of Spanish-speaking migrant workers. These Promotoras are also trained to do family planning counseling. They provide information about contraception and STI testing to individuals, small groups in rural communities, and at health fairs. |

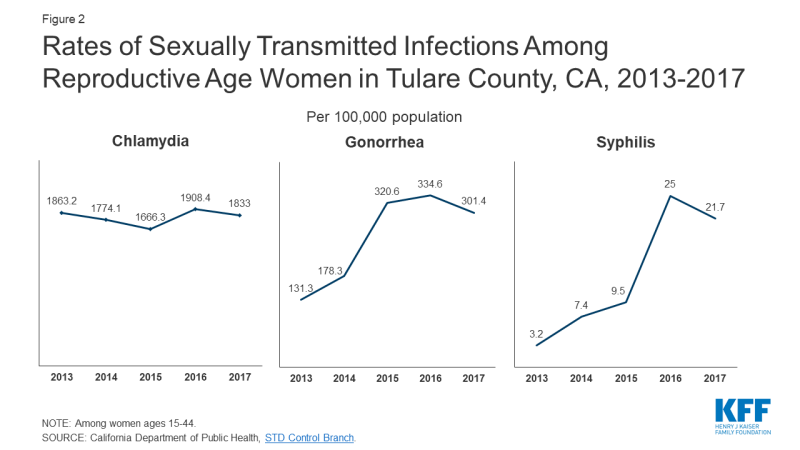

In recent years, the county has experienced a rising rates of some STIs, especially syphilis and HIV. Providers have seen an influx of new STI diagnoses (Figure 2), especially among young people. Some attribute this to the small communities of students who are dating each other. Interviewees had mixed views about whether there are enough providers offering STI or HIV testing in the county. One interviewee suggested that many providers do not test for syphilis, and as a result, Tulare County experienced a large outbreak a few years ago; one provider reported they are still seeing one new case of syphilis each week on average. Clients diagnosed with HIV are often 20-25 years old and mostly male. Another provider suggested that most of the testing happens at the county public health clinics where there are concerns about confidentiality and a mistrust of some providers. Sometimes there is also a fear among patients of being “put on a list” [related to immigration] resulting in people going without care.

“Even if they have [HIV], they are not going to tell us [parents]. It is a sin to talk about that, at least in this area. That’s not something you talk about at dinner time.”

–Focus group participant

Figure 2: Rates of Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Reproductive Age Women in Tulare County, CA, 2013-2017

Access for Special Populations

Undocumented immigrants, people in remote areas, women experiencing domestic violence, LGBTQ individuals, and teens face increased barriers to health care. Tulare County has a variety of community organizations that offer innovative programs focused on improving access for many of these populations.

Immigrants

Barriers affecting low-income women living in Tulare County are amplified for undocumented women. They face additional challenges related to language, costs, and confidentiality. While most of the region’s population is Latinx (65%), there are a number of smaller immigrant communities, including from South and Southeast Asia. Interviewees said that most providers have materials in Spanish and interpretation services or Spanish-speaking staff, but they often do not have the capacity to provide intepretation services for the community’s Southeast Asian populations. Furthermore, providers reported that interpretation in all languages, including Spanish, for ongoing services such as case management is challenging. Many women bring in family members or friends to interpret for them, but providers expressed concern about confidentiality, especially in smaller communities.

Undocumented individuals delay or avoid seeking health, social, or financial services. They may limit their time outside because they fear deportation or a negative impact on their legal status. Multiple interviewees reported that racism and fear of ICE raids have increased in recent years. Several focus group participants recounted experiences in which they delayed or went without health or pregnancy-related care because they were undocumented and afraid of deportation. Women seeking legal status have also forgone needed public assistance, fearing being seen as a “public charge” and jeopardizing the immigration process. There have been ICE raids on domestic violence shelters across California, and interviewees said that women who call to report abuse will not seek services for fear of deportation.

“If you ask for public assistance while your documents are being processed, they are not going to give you your legal status. That’s why many people don’t want to get [assistance]. Because you are in the process, and they are going to see and think ‘these people are going to be a public burden.’”

–Focus group participant“I was undocumented for a long time, and you feel afraid, you feel scared from going [to a health care provider].”

–Focus group participant

Undocumented women in California are eligible for emergency Medicaid coverage of labor and delivery, but their eligibility for Medicaid ends after childbirth. However, under the state’s new expansion of Medi-Cal benefits to young adults 19-25, some would remain eligible for coverage. Several women in the focus group became uninsured following delivery or the 6-week follow up visit. As a result, they did not seek additional care for themselves because they were not covered and felt they could not afford it.

“When I got pregnant [with] my little girl, I didn’t go to the hospital until I was 8-months pregnant because I didn’t know, and I was undocumented.”

–Focus group participant

Poverty and Access in Outlying Areas

Women in the focus group and other interviewees reported that poverty is disproportionately hard on women and plays a role in access to contraception. Visalia, Tulare, and Porterville are the largest towns in the county, but a significant portion of the population lives in unincorporated communities that may not have a grocery store, pharmacy, or health clinic. This leaves many women without even a place nearby to purchase condoms. Some smaller communities do not have running water. Many residents are under- or unemployed and cannot afford housing, food, and hygiene items. Social service providers asserted that when women must make a choice among basic needs, their health is low on the list. One interviewee added that multi-generational poverty locks women who are financially dependent or must work multiple jobs into family environments that prevent them from making their own choices, particularly women in abusive or coercive relationships.

“We are not a woman’s health-friendly community. We have needs that are not being met. Most of the people we serve are women in our communities, but families in our rural communities often don’t have strong networks, education, or access to information [rely on information online]. Young women don’t know where to go.”

–Interviewee

Domestic Violence

Domestic violence is prevalent in the area, but there is a shortage of services and lack of appropriate training among health care providers and law enforcement. The largest victims’ services provider in the county operates the only rape crisis center serving Tulare County. They serve about 350 clients a year, 100 of whom require rape kits/forensic exams. They also operate one of the two emergency shelters in the area; the other is religiously affiliated. Both shelters have long waiting lists due to their limited capacity, housing only eight to ten women, many of whom have multiple children. In addition, barriers facing undocumented individuals in seeking health care services, such as fear of deportation, have also prevented women from utilizing shelters.

“Given recent national changes, we have seen the impact in victims’ services – we have people calling daily to report abuse but will not come into a shelter because of a fear of being connected with the government and deported. We are sure this is happening in other health care organizations.”

–Caity Meader, CEO, Family Services of Tulare County

While screening for domestic violence is recommended as a routine part of primary and prenatal care, health care providers may not screen for it because they do not feel equipped to address the patient’s needs if they disclose abuse. In order to increase domestic violence screening, the victims’ services provider has established operating agreements with hospitals and other health care providers to offer training and education to identify and address domestic violence and abuse among patients. However, they reported implementation challenges at the provider level and that they are not receiving the expected volume of referrals from the clinics.

Most women in the focus group reported that their doctor had discussed domestic violence with them. A few had negative experiences with law enforcement; one focus group participant described how police threatened to remove her children from her custody while she was at the hospital seeking medical attention for injuries due to domestic violence. Because she did not want to accuse her partner, the police implied that the situation was her fault instead of connecting her with resources and support. A few women had positive experiences with police and social workers who helped them obtain the support they needed.

“I did live a lot of domestic violence, I thought they [law enforcement] were going to help me, but they did the complete opposite…they were telling me that they were going to put me in jail because…I was complicit because I didn’t want to accuse him. They were also saying I was exposing my children to that and they were going to take them away from me.”

–Focus group participant

| Initiative: Domestic violence high risk team |

| Family Services of Tulare County, in partnership with the Sheriff’s Office, created a Domestic Violence High Risk Team to address the high rates of domestic violence-related deaths in the county (11 between 2017 and 2018). Tulare County’s domestic violence team is the only example of this model that has been fully implemented west of Ohio. The Sheriff’s team uses a modified danger assessment tool that reviews for evidence-based lethality indicators. If a situation is considered high risk, a collaborative team consisting of staff from the DA’s office, probation, family services, and the Sheriff’s office will meet to address the situation. After implementation of this model, Tulare County did not have any domestic violence-related deaths for an entire year. They plan to expand this model to other areas. |

Women who are involved in abusive relationships often experience reproductive coercion. A victims’ services provider and a family resource center reported that women in abusive relationships often experience reproductive coercion where their partners prevent them from using contraception or sabotage their chosen method. As a result, women are not able to make their own reproductive decisions, and many have had multiple children they did not intend to have. These interviewees reported that when they speak to their clients, it is often their first time learning about family planning options and where to obtain those services. Their staff are trained in identifying women and children who might be experiencing abuse.

LGBTQ Individuals

Individuals who identify as LGBTQ in Tulare County experience significant stigma, and interviewees spoke about a severe shortage of culturally competent providers. The stigma that LGBTQ individuals experience plays a large role in discouraging them from seeking appropriate care. This is compounded for LGBTQ individuals who are Latinx, migrant workers, undocumented, or live in the outlying more rural areas. Some interviewees are also concerned that there is a lagging standard of care for this population compared to other metropolitan areas of the state. For example, providers are still drawing blood to test for HIV rather than using a rapid result test which delays results. In addition, some interviewees said that patients are not always aware that they need to request the specific HIV and STI tests they want to receive.

There is reportedly only one provider in the area who provides culturally competent care for transgender patients, but he will not initiate hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Patients seeking this treatment must travel far out of the county to obtain it.

| Initiative: LGBTQ+ leadership academy |

| The SOURCE is the sole LGBTQ advocacy and resource center in Tulare County. Opened in 2016, the center provides youth and peer support groups and advocates for LGBTQ-friendly policies and practices in the health care system. They also offer education and counseling about medical care including STIs, HIV, substance abuse, and mental health. Its LGBTQ+ Leadership Academy teaches youth about LGBTQ history, HIV care, transgender rights, health equity and reproductive justice, local government, public speaking, and state advocacy. As part of the curriculum, youth perform two clinic visits to compare experiences with health care providers and identify LGBTQ-friendly clinics and physicians. |

There is a lack of primary care doctors who are trained to prevent HIV among at-risk patients. Preliminary data on HIV rates in Tulare County show a 68% increase from 2017 to 2018.2 California state law requires medical providers to educate patients who are at high risk for HIV infection about methods to reduce their risk, including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). However, one interviewee asserted that no providers in the Tulare County area are complying with the mandate. There are no self-reported PrEP providers on official listings online, and an interviewee noted that providers in the area refer individuals seeking PrEP to the one infectious disease physician serving patients with HIV, who has a months-long waiting list. Notably, most women in the focus group had not heard of PrEP or its brand name, Truvada. Providers are also not providing expedited partner therapy (EPT) or HIV/STI prevention education. The SOURCE, the single LGBTQ advocacy resource organization in the county, is trying to change this by working with the FQHCs in the area and conducting clinic visits. The SOURCE is also a PrEP Medication Assistance Program site, through the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) and Gilead’s PrEP Assistance Program (PrEP AP) which helps under- or uninsured individuals pay for the drug.

Teens

“All the other doctors made me feel as if it was a sin being pregnant. Like if I was a shame for the community.”

–Focus group participant

| Initiative: Evaluating access to emergency contraception through youth-led secret shopping |

| ACT for Women and Girls (ACT) is a local grassroots organization with over 14 years of experience in reproductive justice organizing. ACT offers youth-led programming with a focus on reproductive health and provides comprehensive sex education in schools. The organization also has been conducting a pharmacy access project since 2009 where youth secretly shop at 60-70 pharmacies each year in Tulare County to evaluate access to emergency contraception (EC) based on a set of criteria including accessibility (e.g., location in store), youth-friendliness, and men’s experiences purchasing EC (to assess assumptions about gender). ACT develops an annual report card and issues awards to high-performing pharmacies. The organization also conducts secret shopping in health clinics to evaluate how providers and staff treat pregnant teens, transgender people, and people who believe they might be pregnant. |

Access to Abortion Counseling and Services

Compared to many other states, there are fewer restrictions on abortion in California; however, access to and cultural attitudes about abortion vary throughout the state. There are no abortion providers in Tulare County, and interviewees and women in the focus group stated that the community is conservative, creating substantial local resistance among both women and providers to the service.

There are no abortion clinics in Tulare County, and there are significant barriers to providing or obtaining these services. The closest clinic providing abortion services is in Fresno, which is at least 50 miles away. Women face barriers related to transportation, cost, stigma, and fear of family members finding out.

“If you don’t have a car, you don’t get there [to an abortion provider].”

–Focus group participant

Interviewees suggested abortion access is most affected by political and cultural norms, and that anti-abortion groups and crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs), which typically offer limited medical services like pregnancy testing and ultrasounds, and discourage women from seeking abortion services, have considerable local power. Planned Parenthood’s Visalia Health Center has experienced repeated vandalism over the past few years, even though it does not provide abortion services. Local FQHCs fear losing federal funding if perceived as supporting abortion. One interviewee remarked that there is significant bias against abortion among providers and believes that most do not discuss or provide referrals for abortion. Some providers are aware of the potential impact of the new Title X regulations that ban Title X funds from going to providers who offer or refer for abortion services. However, they do not think it will have much of an impact in their community because, “no one is really doing those activities now.”

Half of the focus group participants knew where they could get an abortion, though some suggested that many in the Latinx community oppose abortion. One woman had a friend who wanted an abortion but could not get one because it was too expensive; in the end, she gave birth and placed the baby for adoption. Another woman said she decided to have her provider induce a “miscarriage” after she found out her fetus was developing abnormally, but later doubted her decision. A Title X provider remarked that “we don’t get that many women who want to terminate their pregnancy,” though many interviewees reported a general lack of knowledge and education about abortion as an option.

“It’s really hard to get an abortion here. I don’t know how to emphasize that enough.”

–Erin Garner-Ford, Executive Director, ACT for Women and Girls

Conclusion

California is known for its progressive policies and has extensive protections for health care coverage including family planning and abortion; however, many residents of Tulare County lack access to these services. While the county has a large Medicaid-eligible population, the shortage of providers, particularly specialists and abortion providers, presents barriers to sexual and reproductive health care. In addition, the region’s rural population has little access to public transportation, and faces extreme poverty, making it difficult to afford even basic items. The county’s large Latinx immigrant community, many of whom are undocumented migrant workers, faces heightened challenges; they are often deterred from seeking care due to language barriers, ineligibility for public programs, and a fear of deportation. There is limited support for women experiencing domestic violence, and many face barriers to leaving violent relationships. All these obstacles are amplified for undocumented individuals without health coverage and who fear deportation, and for those who identify as LGBTQ dealing with stigma and a lack of culturally competent providers.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the individuals that participated in the structured interviews for their insights, time, and helpful comments. All interviewees who agreed to be identified are listed below. The authors also thank the women who participated in the focus groups, who were guaranteed anonymity and thus are not identified by name.

Angel Avitia, Assistant Director, Tulare County Family Resource Center Network

Gabriela Beltran, Title X Patient Care Coordinator, Altura Centers for Health

Brandon Foster, PhD, Chief Quality and Compliance Officer, Family HealthCare Network

Erin Garner-Ford, Executive Director, ACT for Women and Girls

Raquel Gomez, Director of Community Initiatives, Tulare County Family Resource Center Network

Caity Meader, CEO, Family Services of Tulare County

Brian Poth, Executive Director, The Source

Leonora Sudduth, RN, Title X Nurse, Altura Centers for Health

Dawn Wells, Grants Specialist, Altura Centers for Health