Sterilization or Permanent Contraception as a Family Planning Method

Sterilization or permanent contraception is the most commonly used form of family planning in the United States. There are two main methods of sterilization: tubal ligations and vasectomies. Both are safe and nearly 100% effective in preventing pregnancy. The Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) contraceptive coverage requirement applies to sterilization procedures for women, but not for men. Some states, however, have passed laws that require male procedures to be covered by state-regulated insurance plans. Permanent contraception services, however, are not available in all health care settings due to policies followed by faith-based health providers that have religious objections to the procedures. This fact sheet explains the types of permanent contraception or sterilization procedures available, reviews private insurance and Medicaid coverage policy, and discusses issues that affect availability in the U.S.

Types of Sterilization

Tubal Ligation

Tubal ligation is an outpatient surgical procedure conducted on people with female reproductive organs in which the fallopian tubes are either removed or blocked to prevent eggs from travelling to the uterus and sperm from fertilizing eggs. Data from the 2024 KFF Women’s Health Survey show that one in four women between the ages of 18 and 64 report they have had a sterilization procedure. Larger shares of women 50 years old and older, women with lower incomes, and women with Medicaid have had a sterilization procedure (Figure 1).

There are two main methods of surgical tubal ligation: mini-laparotomy (or a minilap) and laparoscopic sterilization (Table 1). The minilap can be performed immediately postpartum, right after childbirth, while the laparoscopic procedure cannot. Tubal ligation procedures are effective immediately and have a failure rate of less than 1% within the first year of having the surgery. After 10 years, the failure rate can increase to 18 to 37 pregnancies out of 1,000 women depending on how the fallopian tubes are closed. Complications are rare, but they can include bleeding, infection, and ectopic pregnancy. While the procedure sometimes can be reversed, the process is costly, invasive, typically not covered by insurance, and not guaranteed to work. Sterilization does not protect against sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Vasectomies

A vasectomy is an outpatient procedure done on people with male reproductive organs and is typically done under local anesthesia. In the traditional procedure, a doctor will clip, cut and tie, or cauterize the vas deferens. There is also a newer “no-scalpel” technique which is less invasive, reducing complications and recovery time (Table 1). Despite lower frequency of use compared to tubal ligations, vasectomies are safer, cheaper, and even more effective. Only one out of every 10,000 women will become pregnant using this contraceptive method; however, vasectomies are not effective immediately. It can take two to four months for sperm to be reabsorbed or ejaculated, so an alternate form of contraception should be used to prevent pregnancy. Vasectomies also do not protect against STIs.

The 2024 KFF Women’s Health Survey, found that one in ten (11%) men ages 18 to 64 say they have undergone a sterilization procedure. The share who have been sterilized is higher among white men, men with higher incomes, and men with private insurance (Figure 1).

Insurance Coverage

Sterilization is a highly cost-effective method of contraception. Although it can have high upfront costs, it typically requires no long-term follow-up care and therefore can be cheaper in the long run than other methods. Depending on location, insurance, and procedure type, the out-of-pocket cost of tubal ligation procedures may range from $0 to $6,000, whereas a vasectomy may cost between $0 and $1,000.

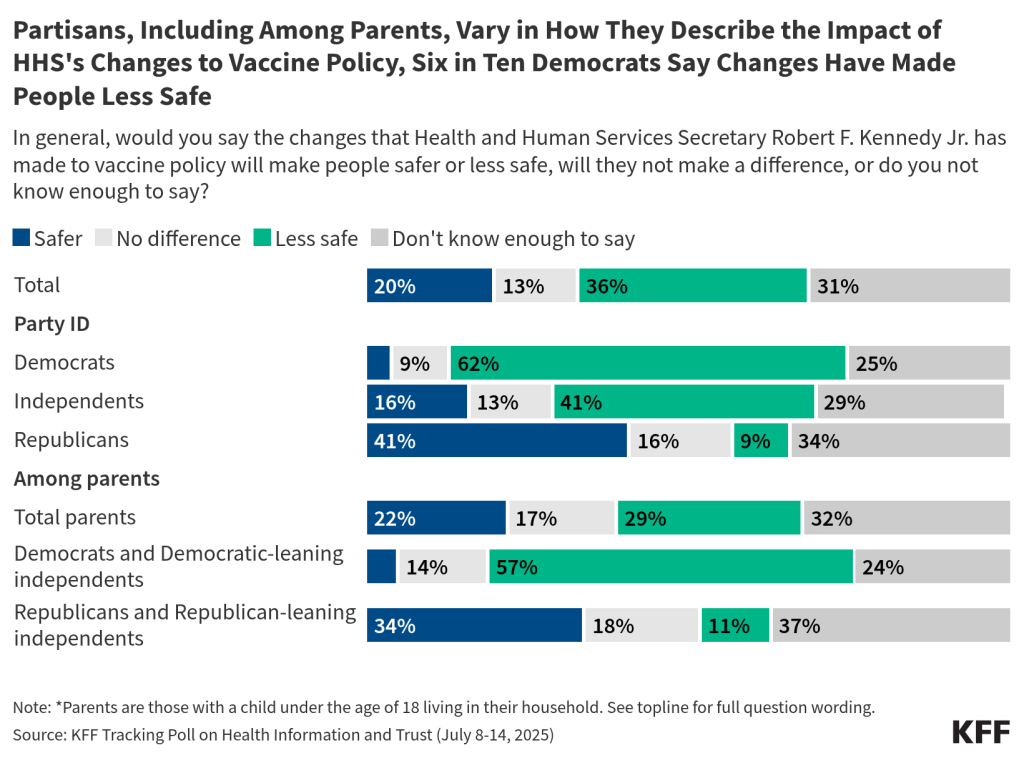

Private Insurance and Affordable Care Act

The ACA requires private health insurance plans to cover at least one form of all 18 FDA-approved contraceptive methods for women without cost sharing, meaning tubal ligation procedures must be fully covered by most private health insurance plans. This federal policy does not include vasectomies; however, nine states—California, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington—require state-regulated private health insurance plans to cover vasectomies at no additional cost to the patient (Figure 2). State-regulated benefit requirements do not apply to self-insured employer plans, though, which covered 63% of covered workers in 2024.

Medicaid

Medicaid, the national health coverage program for low-income individuals, is financed and operated jointly by the federal and state governments. Under Medicaid, it is mandatory for states to cover family planning, including sterilization procedures for women. Vasectomies are not federally required to be covered under any of the Medicaid pathways, but a KFF state survey found that most states report they cover the procedure.

Regulations prohibit federal funds from being used for sterilization procedures on women younger than 21 years old. They also require patients to sign an informed consent form at least 30 days prior to the procedure, with some exceptions. In the event of a premature delivery, consent must have been obtained at least 30 days prior to the due date. However, if a premature delivery or emergency abdominal surgery occurs within the 30-day waiting period, the physician must certify that consent was obtained at least 72 hours after the date on the patient’s signed consent form. This provision was implemented to guard against coercive practices and abuses that were historically directed towards women with low incomes, women with disabilities, women of color, and incarcerated women. However, some advocates suggest that this requirement places a burden on publicly insured women seeking sterilization services that women with private insurance do not face.

Uninsured

Some states have extended access to family planning services to uninsured populations through the Medicaid family planning expansion program that provides Medicaid coverage solely for family planning services to women and men who do not qualify for full Medicaid benefits. These programs are available in 32 states as of January 2025, and most report that they cover tubal ligations and vasectomies.

Although most public funding for sterilization comes from Medicaid, a share is provided by the federal Title X National Family Planning Program and the Maternal and Child Health and Social Services block grants. Changes to federal funding for clinics providing family planning programs may impede access to sterilization services for those who rely on these programs for reproductive health coverage.

Religious Providers

Currently, federal and state laws allow providers with religious objections to refuse sterilization services to patients. The Church Amendments prohibit the federal government from requiring a provider to assist in abortion or sterilization services if they violate the provider’s religious beliefs. As of 2023, 19 states have laws that allow some health care providers to refuse to provide sterilization services for religious reasons (Figure 3). In areas with a limited choice of health care providers, refusal policies could limit the availability of sterilization services.

Another challenge to the availability of sterilization services is the growing number of acute care hospitals that are affiliated with the Catholic Church. These hospitals usually adhere to the religious restrictions required by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, which prohibit the use of sterilization. These directives also prohibit referrals for contraception, abortion, and sterilization services. As of 2020, 7 of the 25 largest health systems nationwide are Catholic-affiliated. There is concern that the growing dominance of Catholic hospitals in some areas may limit access to tubal ligations and post-delivery sterilization procedures. The lack of a postpartum sterilization option could pose a particular challenge for women in communities where the only hospital available to them is part of a Catholic health system (Figure 4). Catholic-affiliated hospitals receive a share of their revenue from public sources, such as Medicaid and Medicare, and serve diverse populations who may not be aware of the limits placed on their care, nor follow the hospital’s religious tenets.

Impact of the Dobbs Ruling

The reproductive health landscape in the United States has drastically changed since the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in 2022 and contraceptive choices have also changed in response to the ruling. A KFF survey found that in 2023, four in ten (43%) OBGYNs reported an increase in the number of patients who sought sterilization since Dobbs. A little over half (51%) of OBGYNs in states with abortion bans or restrictions reported the same, compared to 36% of OBGYNs in states where abortion is legal. Research suggests that the demographics of individuals seeking sterilization may have changed since the Dobbs decision, though it is important to note that the research is limited, and long-term trends continue to be studied. Although sterilization is most common in individuals over 35 years old, a limited number of studies found that the number of sterilization procedures performed on adults under 35 years old increased post-Dobbs. In addition to being younger, similar research has found that a higher share of men who underwent vasectomies or sought consultations since Dobbs are childless and single.