Compare the Candidates on Health Care Policy

The following content was last updated on October 8, 2024

The general election campaign is underway, spotlighting former President Trump, the Republican nominee, and Vice President Harris, the Democratic nominee, as the viable contenders for the presidency. Although health care reform may not be a central issue in this election as in the past, health care remains a significant concern for voters. Trump and Harris have distinctly different records and positions on health care. This side-by-side analysis provides a quick resource for understanding Trump’s presidential record and Harris’ record in the Biden-Harris administration and in previously held public office, as well as their current positions and proposed policies. Proposals are from when candidates served as president and vice president respectively unless text or links indicate otherwise. This tool will be continuously updated as new information and policy details emerge throughout the campaign.

Affordable Care Act

- In 2017, unsuccessfully attempted to repeal and replace the ACA with various plans that would have increased the number of uninsured Americans to 51 million.

- Deprioritized enforcement of the individual mandate penalty, then reduced the penalty to $0.

- Stopped payments for cost-sharing subsidies (CSRs), which contributed to premiums increasing, as well as federal subsidies growing.

- Reduced funding for outreach, which may have contributed to enrollment stagnating.

- Expanded non-ACA-compliant short-term plans, which restrict coverage for pre-existing conditions.

- Allowed Enhanced Direct Enrollment in ACA plans through online brokers.

- In budget plans, proposed changes to the ACA that would weaken pre-existing protections and reduce funding substantially through a block grant to states.

- As a candidate for this election, he called to “never give up” on repealing the ACA, later adding “Obamacare Sucks” and that he would replace it with “much better healthcare.” He also said he was not running on terminating the ACA and would rather make it “much much better and far less money,” though has provided no specific plans.

- The Biden-Harris administration enacted the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), which temporarily expanded eligibility for and increased ACA Marketplace subsidies. These were extended by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) through 2025.

- The administration fixed the “family glitch,” allowing dependents of people with unaffordable employer-based family coverage to receive ACA subsidies.

- The administration reversed Trump administration expansion of short-term plans and restored outreach and enrollment assistance and funding.

- The administration achieved record-high enrollment in ACA Marketplace plans.

- Proposes to build on provisions in the IRA by making permanent the expanded ACA subsidies.

Medicaid

- Supported unsuccessful efforts to repeal and replace the ACA, including the Medicaid expansion, and proposed restructuring Medicaid financing into a block grant or a per capita cap as well as limiting Medicaid eligibility and benefits. These proposals, included in Trump budget plans as president, were estimated to reduce federal Medicaid spending by roughly $1 trillion over 10 years.

- Approved waivers that included work requirements as a condition of Medicaid eligibility, premiums, and other eligibility restrictions.

- Took administrative action to relax Medicaid managed care rules and increase eligibility verification requirements.

- Signed legislation that included a continuous enrollment requirement in exchange for enhanced federal Medicaid funding during the COVID-19 public health emergency.

- Championed Biden-Harris administration efforts to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, including encouraging states to adopt the postpartum Medicaid coverage extension.

- The administration supported legislation to establish a federal option to close the coverage gap (not passed by Congress) and passed a fiscal incentive for states to newly adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion.

- The administration withdrew demonstration waivers approved in the Trump Administration related to work requirements, and encouraged waivers to expand coverage, reduce health disparities, address the social determinants of health, and help individuals transition out of incarceration.

- The administration issued comprehensive regulations and guidance to streamline enrollment, promote continuity of coverage and to help bolster access in Medicaid fee-for-service and managed care.

GO DEEPER: What the Outcome of the Election Could Mean for Medicaid

Abortion

- Takes credit for overturning Roe v. Wade by appointing three anti-choice judges to the Supreme Court, claiming, “After 50 years of failure, with nobody coming even close, I was able to kill Roe v. Wade.”

- Has said he would consider a national 15 or 16-week ban on abortion, but more recently has said he supports leaving abortion policy to states, which allows full bans to stay in effect and tweeted that he would veto a federal abortion ban. Supports exceptions in cases of rape, incest, and to save the life of the pregnant woman.

- Has stated that he would generally not use the Comstock Act to ban mail delivery of medication abortion pills, but will be coming out with specifics.

- Administration issued regulations that blocked clinicians from providing counseling that includes abortion information or referrals in clinics that receive federal Title X family planning funds.

- Reinstated and expanded Mexico City Policy prohibiting U.S. global health funds from going to foreign NGOs that perform or promote abortions.

- As an outspoken defender of reproductive rights and the leading voice of Biden-Harris administration’s stance on abortion, has highlighted the harmful impacts from the Dobbs ruling and advocated for protecting abortion access, including for travel, privacy, emergency care, and bodily autonomy.

- As part of national “Fight for Reproductive Freedoms” tour, the only vice president or president to visit a Planned Parenthood clinic while in office.

- Supports a federal law to restore Roe v. Wade’s national standard of abortion legality up to viability and has also stated she supports eliminating the Senate filibuster to do this.

- The administration’s FDA revised restrictions on medication abortion pills, allowing dispensing via certified pharmacies and telehealth.

- The administration issued guidance affirming that abortions performed to stabilize the health of people experiencing pregnancy-related emergencies are protected by the federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), even in states that ban abortions.

- The administration has defended abortion access and the administration’s actions in two major Supreme Court cases on medication abortion and emergency abortions.

- The administration strengthened HIPAA protections for data privacy, added nondiscrimination protections for people seeking abortion care, and defends right to travel to seek abortion.

- The administration revoked Trump’s Mexico City Policy restrictions.

- As U.S. senator, opposed Hyde Amendment, co-sponsored Women’s Health Protection Act, which would have blocked states from imposing restrictive policies limiting access to abortion, and voted against a bill that would have banned abortions later in pregnancy.

- As attorney general in California, supported state’s Reproductive FACT Act, requiring so called crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs) to post information about availability of free and low-cost contraceptives and abortion services in the state.

- During 2020 primary, while Roe v. Wade was still in place, proposed a pre-clearance requirement that states trying to pass pre-viability abortion restrictions must obtain federal approval.

Contraception

- Prohibited family planning clinics such as Planned Parenthood that also offer abortion services (with separate funding) from receiving funds from the federal Title X family planning program, leading to the disqualification or departure of approximately 1000 sites – about 25% of participating clinics.

- Issued regulations allowing nearly any employer with a religious or moral objection an exemption from the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement.

- Approved Texas’s Medicaid program waiver blocking Medicaid payments to Planned Parenthood and other clinics for non-abortion family planning services and excluding coverage of emergency contraceptive pills in state’s family planning program.

- Supports ACA and its contraceptive coverage requirement and Biden-Harris administration defended challenge to the preventive services requirements in the Braidwood case.

- The administration restored rules of federal Title X family planning program requiring participating entities to offer full range of contraceptives, pregnancy options counseling (including abortion referral), and re-allowing clinics that also offer abortion services (with non-federal funds) to qualify for the program.

- The administration’s FDA approved first over-the-counter oral contraceptive pills and supports increased access and full coverage.

- Supports policies to expand access to contraceptives for military members and dependents.

GO DEEPER: Harris v. Trump: Records and Positions on Reproductive Health

Maternity Care

- Signed the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018 which provided funding for state, local, and tribal maternal mortality review committees, and administration implemented the Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) model to improve care for pregnant and postpartum women with opioid use disorder

- Supports access to IVF care and would require insurance companies or the government to cover all costs (without detailing implementation or funding), but party platform includes language about 14th Amendment, which many legal experts believe could threaten IVF access

- As a longtime leader on maternal health, she championed Congressional bills to improve pregnancy care and reduce racial and ethnic disparities. This includes extension of Medicaid coverage to one year postpartum (enacted under the Biden-Harris Administration). The Administration issued a Blueprint on maternal health that set cross-agency priorities, including workforce development, enhanced data collection, mental health, and doula coverage

- Supports guaranteed right to IVF and spoke out against the Alabama Supreme Court ruling

LGBTQ Health

- Worked to restrict or remove LGBT rights and access to health care.

- Issued revised regulations on Section 1557 of the ACA removing protections in health care based on gender identity and sexual orientation.

- Created Division of Conscience and Religious Freedom at HHS and issued final conscience regulation broadening nondiscrimination protections for health care entities to include conscience and executive order directing federal agencies to expand religious protections, actions that created opportunities for LGBTQ-based discrimination in certain circumstances.

- Removed and sought to curtail data collection on sexual orientation and gender identity in federal surveys.

- Proposes to prohibit gender-affirming care for young people and limit for people of any age nationwide, including prohibiting the use of federal funds for these services.

- Made campaign commitment to work to pass the Equality Act which would provide non-discrimination protections for LGBTQ+ people.

- Worked to expand and protect LGBTQ rights and access to health care as attorney general of California, as a U.S. senator from California, and through the Biden-Harris administration.

- As attorney general of California, supported marriage equality, which has implications for health care access.

- As U.S. senator, Harris: introduced a bill seeking to include LGBTQ identity in the U.S. Census, which has implications for identifying health care trends for the population; cosponsored The Health Equity and Accountability Act and the Equality Act, bills seeking to promote equity, access, and data collection, including in health care for LGBTQ people, among others; and introduced the PrEP Access and Coverage Act, a bill aiming to increase access to PrEP, an HIV prevention medication.

- The Biden-Harris administration issued guidance and regulations on Section 1557 of the ACA providing the broadest protections to date in health care based on gender identity and sexual orientation, for transgender people, and for gender-affirming care.

- The administration enacted the Respect for Marriage Act, enshrining the right for same-sex couples to marry into law.

- The administration modernized FDA restrictions on blood donation to align with risk rather than identity.

- The administration issued regulation providing protections for LGBTQ people in HHS grants and services.

- The administration rescinded Trump administration regulatory expansions of conscience regulations that had created potential opportunities for LGBTQ-based discrimination (which multiple federal courts had found to be unlawful).

- The administration intervened, through DOJ, to support plaintiffs in lawsuits challenging state bans on youth access to gender-affirming care and has requested SCOTUS review of the state law.

- The administration issued executive order seeking to advance equity for LGBTQ people

- The administration adopted a Federal Evidence Agenda on LGBTQ Equity and an HHS-wide action plan promoting sexual orientation and gender identity data collection and equity in federal programs and surveys.

Gun Violence

- Banned bump stocks in response to the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting, though the ban has since been overturned by the Supreme Court. His campaign stated, “The Court has spoken and their decision should be respected.”

- Reversed Obama-era regulations that required those eligible for Social Security Administration mental disability payments to be blocked from buying guns and made it easier for gun-safety devices to be more widely accessible.

- Asked the Supreme Court to overturn New York City’s restrictions on transporting handguns in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. City of New York, New York.

- On multiple occasions, has suggested that armed citizens could stop mass shootings, including after the Pulse nightclub shooting stating, “you wouldn’t have had the tragedy that you had.” At times, he has partially walked back this suggestion.

- Has frequently attributed community gun violence and violent crime to both mental illness and immigration, stating that “they’re not humans, they’re animals.”

- Trump is a gun owner and has stated in the past that he “always carries a gun.”

- Wants to implement gun safety laws to reduce gun violence, including red flag laws, universal background checks, and a ban on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines. She recently stated, “It is a false choice to suggest that you’re either in favor of the Second Amendment or you want to take everyone’s guns away. I’m in favor of the Second Amendment and we need an assault weapons ban.”

- Disagreed with the recent Supreme Court decision to overturn the banning of bump stocks, used in the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting at a music festival. In a statement after the decision, she called on Congress to ban bump stocks immediately.

- As vice president oversees the newly established White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention, which aims to address gun violence by partnering directly with states and encouraging them to institute their own gun violence prevention offices.

- The Biden-Harris administration supported and signed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act into law, which enhanced background checks for individuals under 21, funds crisis intervention orders, and invests in mental health services, including school-based mental health services.

- The administration issued executive actions to reduce gun violence, including rules to curb the proliferation of “ghost guns,” reclassify some firearms to require stricter regulation, and promote the use of Extreme Risk Protection Orders or “red flag laws.”

- The administration launched cross-jurisdictional strike forces to reduce illegal firearm trafficking in key regions affected by gun violence and stepped up enforcement against firearm dealers who sold firearms illegally or did not abide by background check requirements.

- Through both executive action and the American Rescue Plan Act, the administration funded and supported local public safety and community violence prevention programs.

- As a presidential candidate in 2019, Harris shared that she owned a gun for personal safety, but also called for “reasonable gun safety” laws.

Public Health

- Despite creating Operation Warp Speed, which successfully developed effective COVID-19 vaccines within record time, and initially promoting vaccines, regularly questioned science and public health.

- Consistently downplayed COVID-19 as a health threat and routinely countered federal agency and expert advice on pandemic response, including on school re-openings, testing, and masking. Touted the use of unproven therapies such as hydroxychloroquine and suggested that applying ultraviolet light to or inside the body, or injecting disinfectant, could combat coronavirus.

- Delegated most responsibility for the COVID-19 response to the states, with the federal government serving as “merely a back-up” and “supplier of last resort.”

- Proposed significant budget cuts to CDC and other federal public health programs.

- Has vowed to “stop all COVID mandates” and said he would cut federal funding to schools with a “vaccine mandate or a mask mandate.”

- Said he “probably would” disband the White House Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy, established by Congress in 2023.

- Biden-Harris administration committed to listening to science, public health advice, and evidence-based guidance in the COVID-19 response.

- The administration enacted new federal COVID response policies such as mask and vaccine mandates, expanded access to testing and vaccines, and a major effort to bolster the national public health workforce.

- The administration focused on federal responsibility for giving states “the critical supplies they need.”

- The administration established a new White House Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy.

- The administration initiated a CDC reorganization and modernization project “to better share science and data to better serve and protect the American public.”

- The administration has proposed significant increases in the nation’s public health budget each year, including in the FY 2025 budget, which calls for $20 billion in new mandatory funding for pandemic preparedness and response, and $12 billion over ten years for a new Vaccines for Adults program.

- The administration started new initiatives to combat health misinformation and address health inequities.

Prescription Drug Prices

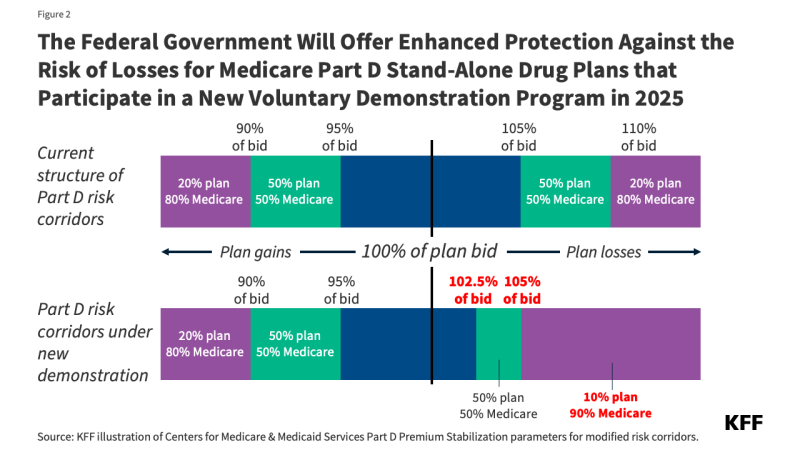

- Established a voluntary model allowing participating Medicare Part D plans to limit monthly insulin costs to $35 (in effect from 2021 through 2023).

- Created a new pathway to allow states to import prescription drugs from Canada.

- Proposed to eliminate drug rebates in Medicare Part D, which was projected to increase Part D premiums and Medicare spending while lowering out-of-pocket costs (implementation subsequently delayed by legislation until 2032).

- Proposed to establish a “Most Favored Nation” system of international reference prices for some Medicare-covered drugs, where U.S. prices would be based on prices in certain other countries (blocked by court action and later rescinded), and to require drug manufacturers to disclose drug prices in television ads (blocked by court ruling). According to the 2024 Trump campaign, “There is no push to renew the most favored nations drug pricing policy.”

- Proposed several Medicare Part D benefit design changes, including an out-of-pocket cap and weaker formulary standards (proposals not implemented).

- As vice president, cast the tiebreaking vote in the U.S. Senate for the Inflation Reduction Act, which requires the government to negotiate prices for some Medicare-covered drugs (with the number growing over time), requires drug companies to pay rebates if prices rise faster than inflation, caps out-of-pocket drug spending, limits monthly insulin costs to $35 for Medicare beneficiaries in Part B and all Part D plans, improves financial assistance for low-income beneficiaries, and other changes.

- Proposes to accelerate Medicare price negotiation of drugs (the Democratic platform calls for 50 drugs per year) and extend $35 insulin copay cap and drug out-of-pocket cap to all Americans. Also stated she will increase competition and transparency, starting with cracking down on pharmaceutical companies blocking competition and abusive practices of drug middlemen.

- The administration approved Florida’s plan to import some prescription drugs from Canada; implementation contingent on further action by Florida.

- The administration delayed implementation of the Trump administration’s drug rebate rule until 2032, which will delay projected increases in Medicare spending.

- The administration established a voluntary model to increase access to cell and gene therapies for people with Medicaid.

Medicare

- Promises to “always protect Medicare, Social Security, and patients with pre-existing conditions” including no changes to the retirement age (no specific policies proposed).

- Proposes to eliminate taxes on Social Security benefits, which would accelerate insolvency of the Medicare Hospital Insurance and Social Security Trust Funds.

- Proposed various policies to reduce prescription drug prices, including a “Most Favored Nation” system of international reference prices and banning drug rebates (neither proposal implemented) and prescription drug importation (final rule issued). According to the 2024 Trump campaign, “There is no push to renew the most favored nations drug pricing policy,” (see also Prescription Drug Prices).

- Enacted tax reductions that accelerated the depletion of the Medicare Part A Trust Fund, and repealed IPAB, a federal board that was designed to help slow the growth of Medicare spending.

- Signed legislation that expanded treatment for substance use disorders and other mental health conditions and allowed Medicare Advantage plans to offer additional benefits for chronically ill enrollees.

- Increased Medicare premiums for higher-income beneficiaries.

- Broadened coverage of telehealth, provided advanced payments to providers, and eased staffing requirements for Medicare-certified nursing homes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (see also Long-Term Care).

- Biden-Harris administration proposes to “protect Medicare for future generations” in part by extending solvency of the Medicare Part A Trust Fund by raising Medicare taxes on high earners and closing tax loopholes, and proposes to expand Medicare and Social Security (details not specified).

- Proposes expanding home care services under Medicare to help people with functional or cognitive impairments (see also Long-term Care), and adds a vision and hearing benefit to Medicare, paid for by expanding Medicare drug negotiations and other policies.

- As vice president, cast the tiebreaking vote in the U.S. Senate for the Inflation Reduction Act, which included several provisions to lower Medicare prescription drug expenses, including negotiated drug prices and a $35 monthly insulin cap (see also Prescription Drug Prices).

- The administration expanded coverage of mental health services and access to additional mental health providers.

- The administration extended broader coverage of telehealth through December 2024.

- The administration established new rules for Medicare Advantage insurers, including restrictions on prior authorization and marketing practices.

- The administration established new staffing requirements for Medicare-certified nursing facilities (see also Long-Term Care).

- During the 2019 Democratic presidential primary, supported a Medicare for all approach with a role for private insurance, however her campaign has since indicated she would not seek to advance Medicare for all as president and has supported the ACA and expansions to broaden coverage and make health care more affordable.

Health Care Costs

- Signed the bipartisan No Surprises Act into law, protecting patients from unexpected medical bills when receiving out-of-network care unknowingly.

- Issued an executive order on price transparency, leading to a rule requiring hospitals to post negotiated charges for their services online using authority from the ACA.

- Proposed establishing a “Most Favored Nation” system of international reference prices for some Medicare-covered drugs. However, this was blocked by court action and later rescinded. According to the 2024 Trump campaign, “There is no push to renew the most favored nations drug pricing policy.”

- Supported efforts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, and in 2024 says he would make the ACA much less expensive (more details in ACA section).

- On his 2024 campaign site, he vows to continue his earlier efforts regarding surprise medical bills, price transparency, and prescription drug prices. He also promises to lower health insurance premiums but does not provide details on how he plans to do so.

- The administration challenged anticompetitive behavior, including health care mergers. Approved, with conditions, a merger between CVS Health and Aetna, one of the largest health care mergers in history.

- Proposes to work with states to cancel medical debt for millions of Americans. In June 2024, Harris announced an administration proposal to remove medical debt from credit reports of 15 million Americans and encouraged state and local governments to act to reduce the burden of medical debt.

- In 2021, the Biden-Harris administration began implementing the No Surprises Act, establishing processes to determine payments for out-of-network bills and resolving payment disputes. The administration also proposed expanding surprise billing protections to ground ambulance providers.

- The administration expanded the Trump-era rules on price transparency to address implementation challenges and enforce the legislation.

- The administration supported the Inflation Reduction Act empowering Medicare to negotiate prices for certain drugs with pharmaceutical companies & increase subsides for ACA marketplace plans (more details in Prescription Drug Prices section).

- The administration issued an executive order promoting competition, released updated merger guidelines, and has challenged anticompetitive behavior in the health care sector. As attorney general of California, joined lawsuits against health care mergers and laid the groundwork for an antitrust case against Sutter Health that settled for $575 million in 2019.

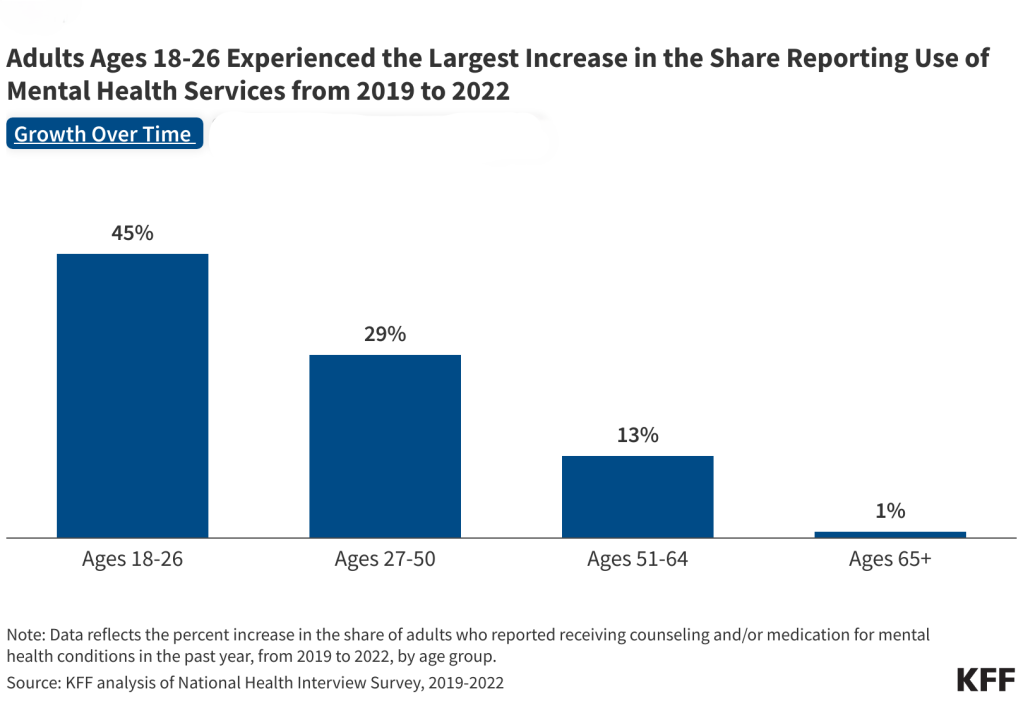

Mental Health

- Proposes a return to mental institutionalization, stating, “for those who are severely mentally ill and deeply disturbed, we will bring them back to mental institutions, where they belong” — moving away from longstanding policies that provide treatment and living in community settings.

- Supported repeal of the ACA and cuts to Medicaid, which would reduce coverage and access to behavioral health services, and issued an executive order to expand non-ACA-compliant short-term policies that often limit or exclude mental health services.

- Signed pandemic legislation (CARES Act) that included an expansion of Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs), signed legislation that established the 988 hotline, and issued an executive order on veteran suicide.

- As vice president led the White House’s Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis, which has taken steps to address maternal mental health, such as launching the National Maternal Mental Health Hotline, training providers on maternal mental health and substance use disorders, and calling on states to expand and extend Medicaid postpartum medical and mental health coverage.

- The Biden-Harris administration made investments to expand mental health and substance use treatment, including to children and families and underserved populations, and to address the mental health workforce shortage by increasing licensing flexibilities for social workers.

- The administration supported and enacted the Safer Communities Act, which included provisions to increase school behavioral health services (building on the administration’s American Rescue Plan Act) and strengthen state requirements for behavioral health care for Medicaid-enrolled youth, in response to worsening youth mental health.

- The administration enhanced behavioral health access opportunities for Medicaid enrollees by establishing maximum appointment wait times, surveying enrollee experiences, and adding rate transparency policies, which may result in improved rates and more provider participation.

- The administration expanded the Medicaid CCBHC Demonstration by adding 10 new states to the program.

- The administration enhanced crisis care by building up 988 and mobile crisis services, and released the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, with focus on high-risk groups (e.g. LGBTQ+, veterans, moms).

- The administration proposed updated requirements for health plans in order to comply with mental health parity.

Opioid Use Disorders

- Declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency, signed bipartisan legislation (SUPPORT Act)

- 2024 campaign proposes a heavier-handed law and order response to opioids, including reviving restrictive border policies, increasing federal law enforcement involvement in local drug investigations, and seeking the death penalty for drug smugglers and drug dealers.

- Plans to support faith-based substance use treatment and job placement but emphasizes a forceful approach for homeless people with mental health and substance use needs, stating ending “the nightmare of the homeless, drug addicts, and dangerously deranged” by arresting or relocating individuals to “tent cities” staffed with health workers on large parcels of inexpensive land.

- The Biden-Harris administration established a multi-pronged response to the opioid epidemic, including reducing the supply of illicit substances like fentanyl, launching educational and awareness campaigns like “One Pill Can Kill” to raise awareness about fentanyl and emerging threats like xylazine, and improving prevention and access to evidence-based treatment.

- The administration reduced barriers to medications for opioid use disorder by updating regulations for methadone dispensing programs to improve access, extending temporary rules that allow buprenorphine administration via telehealth, adding substance use treatment training requirements for providers, removing provider registration requirements prescribing treatment medication, and permanently requiring state Medicaid plans to cover medication-assisted treatment (through the 2024 Consolidated Appropriations Act). The administration extended funding for state and tribal opioid response grants to support states in distributing opioid overdose medication and continuing initiatives that increase access to opioid treatment services and medication.

- The administration expanded access to medication treatment in correctional settings by allowing states with approval to use Medicaid funds for addiction treatment services up to 90 days before release and by updating regulations that improve access to methadone treatment in jails and prisons.

- Following the FDA’s approval of over-the-counter opioid overdose reversal medication under the administration, the White House established the Challenge to Save Lives from Overdose, which is a nationwide initiative to increase training on overdose reversal and improve availability of overdose reversal medication in public and private organizations across all sectors.

Long-term Care

- Proposes to protect seniors by “shifting resources back to at-home Senior Care,” addressing disincentives that contribute to workforce shortages, and supporting unpaid family caregivers through tax credits.

- Issued regulations relaxing oversight for nursing facilities, including removing the requirement to employ an infection preventionist.

- Suspended routine inspections in nursing facilities during early months of COVID-19.

- Launched the Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program to facilitate COVID-19 vaccinations in facilities with residents ages 65+.

- Issued guidance to delay the implementation of the “Settings Rule,” which established new protections for people using Medicaid home and community-based services (HCBS).

- Proposes expanding home care services under Medicare to help people with functional or cognitive impairments, paid for by expanding Medicare drug negotiations and other policies.

- Proposes to partner with private technology companies to expand remote patient monitoring and telehealth and strengthen the home-care workforce.

- Proposes working with Congress to end Medicaid estate recovery, a practice in which the state recoups the costs of Medicaid LTSS from the home and estates of deceased enrollees; or using administrative action to expand the circumstances in which families may be exempted.

- Biden-Harris administration required reporting of COVID-19 vaccination rates in nursing facilities.

- The administration promoted newly established minimum staffing requirements for nursing facilities, including other requirements to support nursing facility workers; issued regulations to increase transparency of private equity ownership of nursing facilities.

- The administration enacted legislation increasing federal funding for Medicaid HCBS; proposed $400 billion in new Medicaid funding for HCBS; established requirements to increase access to Medicaid HCBS, promote higher payment rates for home care workers, and reduce the time people wait for services.

Global Health

- Pursued an “America First” approach to foreign policy, including for global health, prioritizing sovereignty and disengaging from multilateral agreements.

- Halted U.S. funding for the World Health Organization and initiated a process to withdraw U.S. membership in the organization.

- Significantly expanded the Mexico City Policy to apply to virtually all U.S. bilateral global health funding. When in place, the policy requires foreign NGOs to certify that they will not “perform or actively promote abortion as a method of family planning” using funds from any source as a condition of receiving U.S. funding.

- Chose not to join COVAX, the global initiative to distribute COVID-19 vaccines.

- Proposed eliminating/significantly reducing funding for most US global health programs in multiple Presidential budget requests; ended funding for United Nations Family Planning Agency (UNFPA).

- Dissolved the National Security Council’s stand-alone Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense, moving its functions into other parts of the NSC.

- Supported extending the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) initiative for an additional five-year period.

- Biden-Harris administration promotes international cooperation and alliances in foreign policy and global health.

- The administration reversed decision to withdraw from WHO and restored U.S. funding for the organization.

- The administration rescinded the Mexico City Policy that was expanded under Trump. As a Senator, Harris co-sponsored bills to permanently repeal the policy.

- The administration restored funding for UNFPA.

- The administration released a National Security Memorandum and Executive Order that positioned global health as “top national security priority.”

- The administration joined COVAX and committed to the U.S. being the largest donor of COVID-19 vaccines globally.

- The administration re-established the NSC Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense.

- The administration created new, elevated Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy at the State Department.

- The administration supported WHO-based negotiations to develop a new pandemic agreement and to revise the International Health Regulations.

- The administration updated and expanded the U.S. Global Health Security Strategy.

Immigrant Health Coverage

- Issued regulatory changes to public charge policies that newly considered the use of non-cash assistance programs, including Medicaid, in public charge determinations for people seeking to enter the U.S.

- Issued a proclamation suspending entry of immigrants into the United States unless they provided proof of health insurance.

- Rescinded the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, but the Supreme Court ruled the rescission unlawful in 2020.

- Biden-Harris administration rescinded the Trump administration’s public charge changes and, in 2022, issued regulations that largely codified 1999 guidance, which exclude the use of non-cash assistance programs, including most Medicaid coverage, from public charge determinations.

- The administration revoked the Trump administration’s proclamation that suspended entry of immigrants unless they provided proof of health insurance.

- The administration Issued regulations that extend Marketplace eligibility to DACA recipients, which is estimated to lead to 100,000 DACA recipients gaining coverage.

Proposals by Trump to carry out mass deportations of millions of immigrants and executive action by both the Biden-Harris administration and by the Trump administration to have stricter border enforcement may increase fears among immigrant families, making them reluctant to access health coverage and care.