Trends in State Medicaid Programs: Looking Back and Looking Ahead

Section 4: Provider Rates and Taxes

Provider Rates

States have a great deal of flexibility to determine the methodology and amount to reimburse providers. According to federal rules, “provider payment rates must be consistent with efficiency, economy, and quality of care and sufficient to enlist enough providers so that care and services are available under the plan at least to the extent they are available to the general population in the geographic area.” Over the 15 years, Medicaid programs have made a number of changes to provider rates; some trends have emerged.

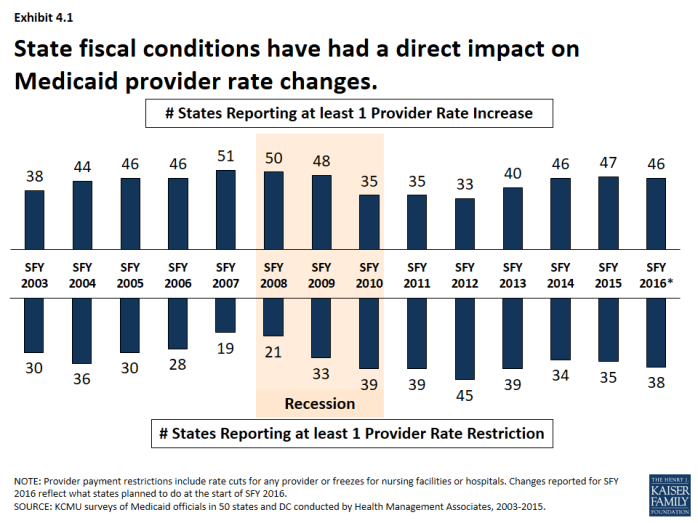

State fiscal conditions have a direct impact on Medicaid provider rates. During economic downturns, states often turn to provider rate cuts to control costs, and when the economy improves, states may restore cuts or work to improve rates. During the Great Recession and its aftermath, the number of states reporting at least one provider rate restriction increased while the number of states reporting at least one provider rate increase declined. More states reported rate restrictions compared to increases for at least one provider rate between SFY 2010 and SFY 2012. (Exhibit 4.1) Economic downturns may have different impacts across provider types.

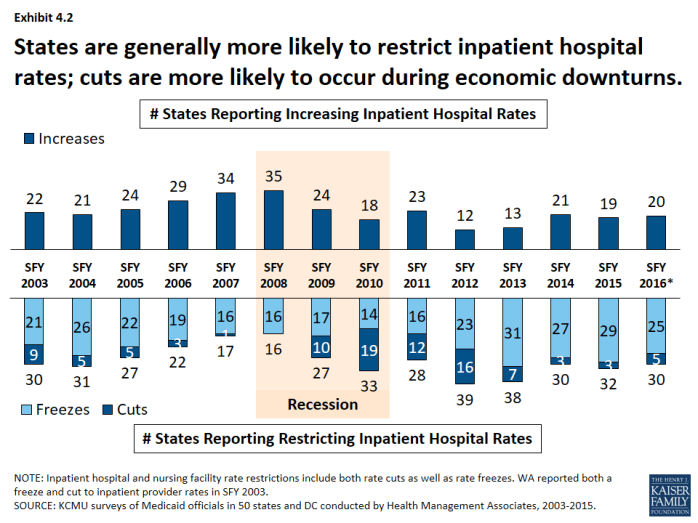

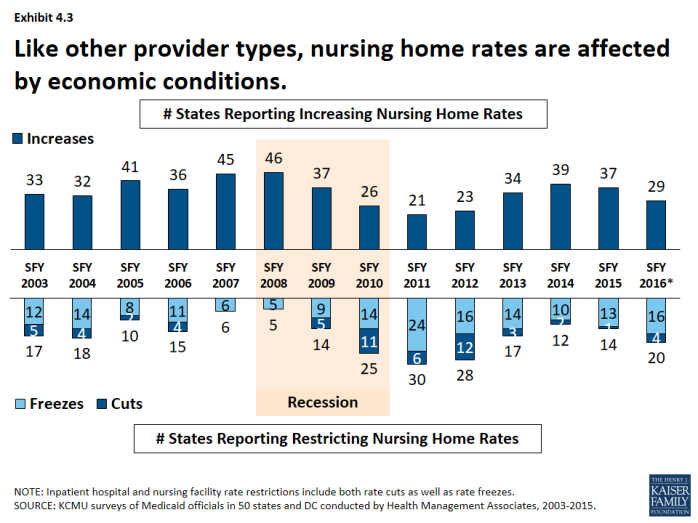

- Institutional providers like hospitals and nursing facilities were more likely to experience rate freezes and not cuts during economic downturns. For this survey, rate freezes for these provider types are counted as rate restrictions. In most years, a small number of states imposed actual rate cuts for these providers rather than freezes. (Exhibit 4.2), (Exhibit 4.3) Climbing out of the recession, many states have maintained freezes for these providers. The number of states with inpatient hospital restrictions (including freezes) has outpaced the number of states increasing rates even after the downturn. (Exhibit 4.2)

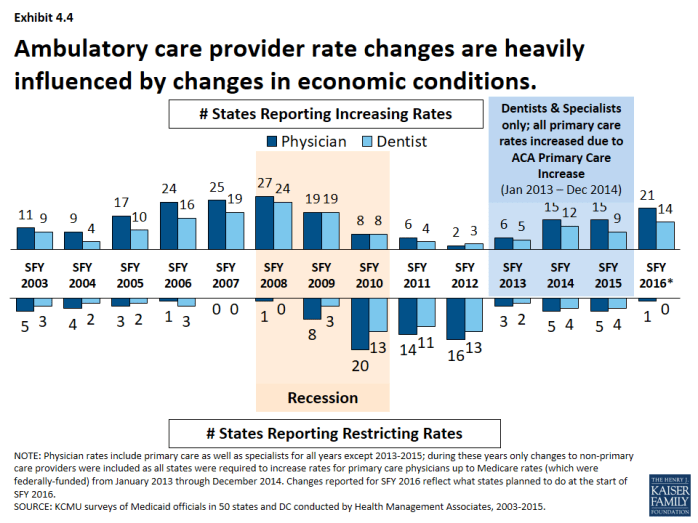

- The number of states reporting rate increases for physicians or dentists increased during the recession and has increased after the recession. (Exhibit 4.4) However, federal policy also influenced some ambulatory care provider rates that are not reflected in this data (See box).1

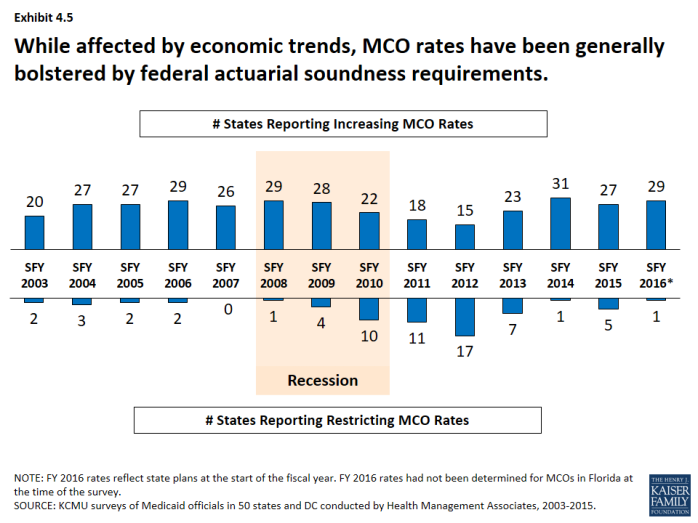

- Managed care rates are generally bolstered by the federal requirement that state capitation rates for MCOs must be “actuarially sound.” MCO rate changes have been affected by economic trends like other Medicaid payment rates, though the number of states reporting MCO rate increases has remained more consistently positive than for other provider types. (Exhibit 4.5)

| ACA Primary Care Increase |

| The ACA required increased Medicaid payment rates for primary care services to Medicare rates from January 2013 through December 2014. The federal government funded 100 percent of the difference between Medicaid rates that were in effect as of July 1, 2009 and the full Medicare rates for these two years. The significance of this rate differential varied greatly across states; a 2012 survey of Medicaid physician fees showed that in a small number of states, Medicaid rates for physician services were already at Medicare rates while other states paid sixty percent or less of Medicare rates. After December 2014, states could elect to continue the increased rate at their regular match rate. About one-third of states reported continuing the rate increase either fully or partially in FY 2015 and FY 2016 while other states reported rate increases unrelated to the ACA primary care rate increase. |

Provider Taxes

Provider taxes are imposed by states on health care services where the burden of the tax falls mostly on providers, such as a tax on inpatient hospital services or nursing facility beds. Provider taxes or fees can be imposed on a number of providers or classes of services. In the past, states were able to use provider taxes and other state financing arrangements increase the effective federal matching. However, legislation enacted in 1991 restricted the use of provider taxes to curb such practices. Under current regulations, states may use provider tax revenues to help finance the state share of Medicaid spending only when the tax meets three requirements: it must be broad-based, uniformly imposed, and cannot hold providers harmless from the burden of the tax.2

Provider taxes have become an integral source of financing for Medicaid. States have used provider taxes to support eligibility, benefit and provider rate increases or to help mitigate provider rate cuts. More recently, at least seven states reported plans to use increased provider taxes to fund all or part of the state cost of the ACA Medicaid expansion that will start in CY 2017 when the 100 percent federal match for the expansion starts to decline.3 States have been more likely to impose or increase provider taxes to help fund the state share of Medicaid during economic downturns.

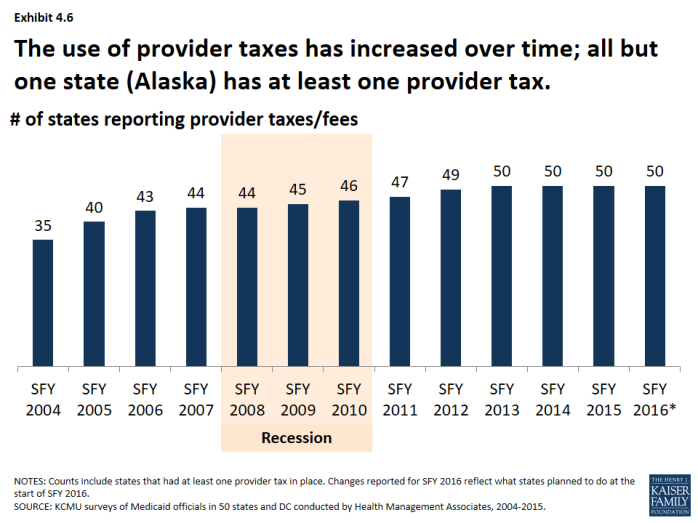

States have increased the number of provider taxes over time. At the beginning of SFY 2004, a total of 35 states had at least one provider tax in place. Over the next decade, a majority of states imposed new taxes or fees and/or increased existing tax rates and fees to raise revenue to support Medicaid. Since SFY 2013, all but one state (Alaska) has had at least one provider tax in place. (Exhibit 4.6)

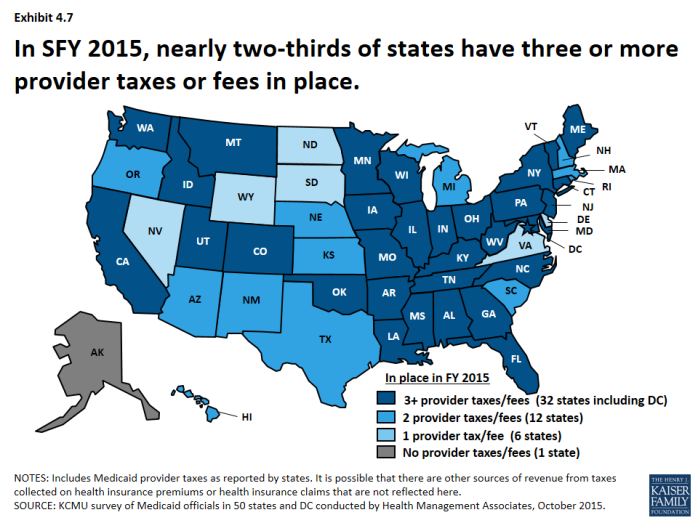

- In SFY 2015, nearly two-thirds of states have 3 or more provider taxes in place. (Exhibit 4.7)

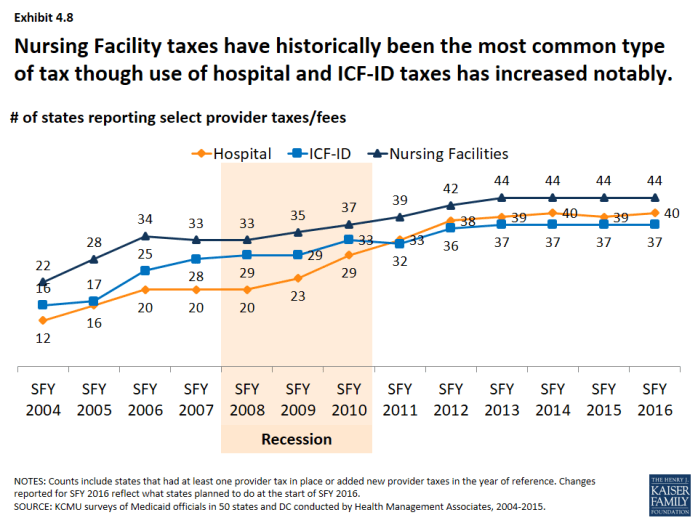

- Nursing facility taxes have historically been the most common type of tax though the use of hospital and ICF-ID taxes has increased notably over time. (Exhibit 4.8)

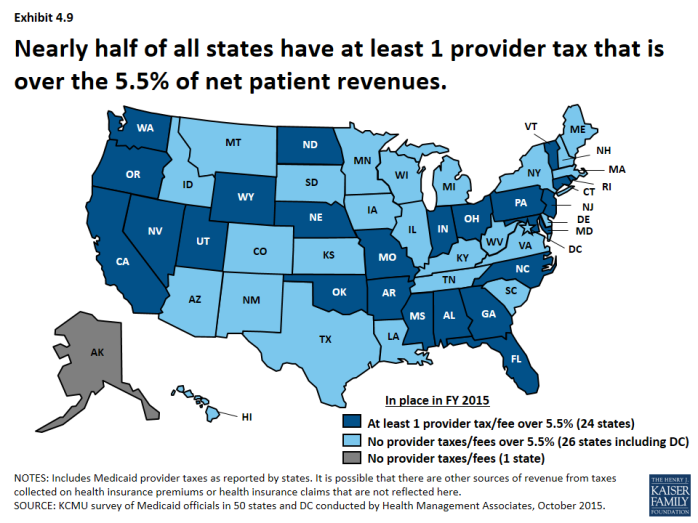

Legislation has been proposed to curtail the use of provider taxes. Under current regulations, states may not use provider tax revenues for the state share of Medicaid spending unless the tax meets certain requirements including that providers cannot be held harmless from the burden of the tax.4 Federal regulations create a safe harbor from the hold-harmless test for taxes where collections are 6.0 percent or less of net patient revenues.5 Recent legislative proposals have suggested lowering the safe harbor threshold from 6.0 percent to 5.5 percent. In 2015, a total of 24 states estimated that at least one provider tax above this 5.5 percent threshold.6 (Exhibit 4.9)