Trends in State Medicaid Programs: Looking Back and Looking Ahead

Section 3: Benefits, Pharmacy and Long Term Care

As a condition of participation in the Medicaid program, states are required to provide a core set of “mandatory” benefits, but states have a great deal of flexibility in determining what optional benefits to cover as well as the amount, duration and scope of benefits covered under the program. Children generally have access to a broader benefit package due to EPSDT (early periodic screening diagnostic and treatment) requirements, but Medicaid benefits can vary widely for adults covered under the program. One optional benefit for adults that all states have elected to cover is pharmacy. States have developed extensive programs to manage this benefit and continue to further refine their policies over time. Another area of focus for state Medicaid programs is long-term care. Medicaid is the nation’s primary payer for long-term services and supports (LTSS) covering a continuum of services ranging from home and community-based services (HCBS) to institutional care provided in nursing facilities. LTSS represents about one-third of Medicaid spending and balancing institutional and community-based care is an important focus for state policymakers.1

Benefits

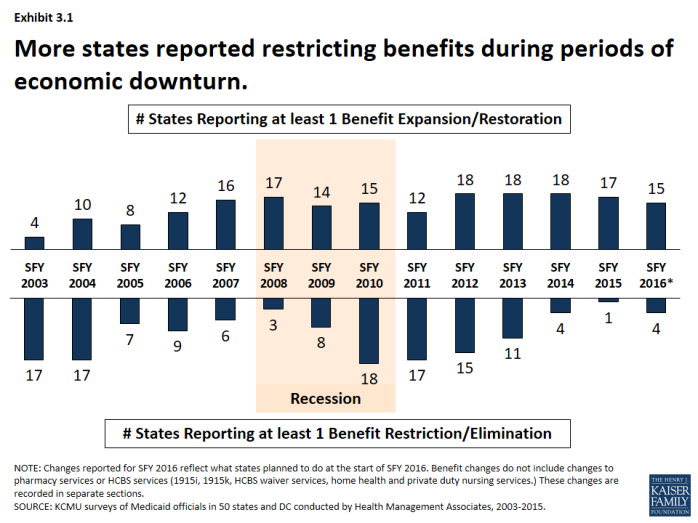

Benefit actions are influenced by economic trends; more states adopt restrictions during downturns and expand or restore benefits as conditions improve. During the Great Recession and its aftermath, the number of states reporting at least one benefit restriction increased, particularly in SFYs 2010 and 2011. (Exhibit 3.1) However, as economic conditions improved, more states reported benefit restorations and expansions than restrictions.

Changes to dental coverage as well as other optional benefits are particularly affected by economic conditions. For example, 16 states restricted or eliminated adult dental coverage in SFY 2003 and SFY 2004; nine of those states restored at least partial dental coverage the following years. During the Great Recession, 19 states reported dental restrictions in SFY 2010 through SFY 2012; eight of these states then reported some restorations in SFY 2013 – SFY 2016.

A number of states have added or expanded behavioral health benefits in recent years.2 Since 2012, half of states (25) have added or expanded behavioral health services. This includes actions to expand mental health services and or substance abuse services.

Pharmacy

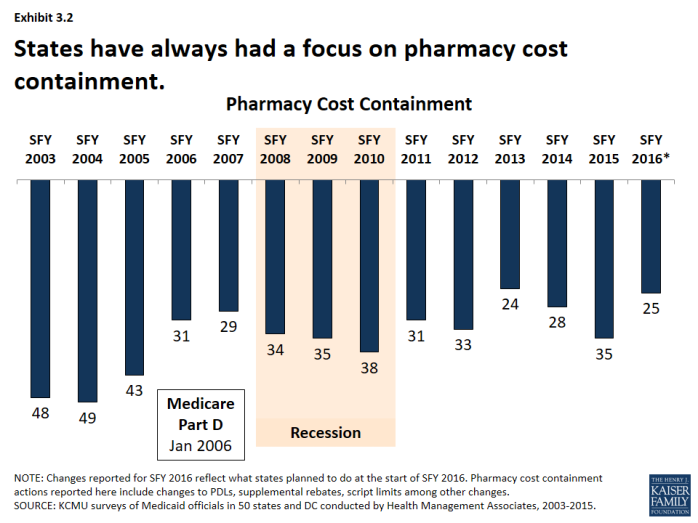

Pharmacy cost-containment has always been a focus of state Medicaid programs, but intensified in response to changes in federal law and industry trends. From 2003-2005, nearly every state implemented policies designed to slow the growth in Medicaid spending for prescription drugs. In January 2006, the implementation of the Medicare prescription drug benefit reduced total state Medicaid drug expenditures by almost half. At the same time, the rate of growth in the cost of prescription drugs abated and the intense Medicaid focus on pharmacy cost containment began to diminish. Since 2015, however, a combination of rising drug prices, particularly for specialty drugs, and increasing enrollments (as a result of ACA coverage expansions) have refocused state attention on pharmacy reimbursement and coverage policies. (Exhibit 3.2)

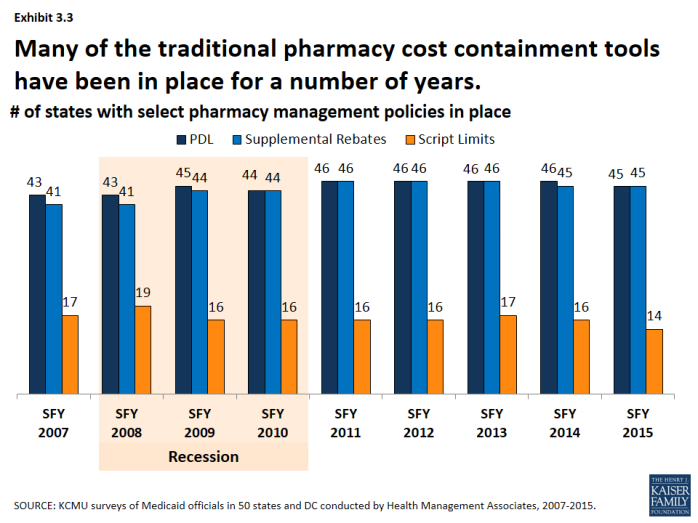

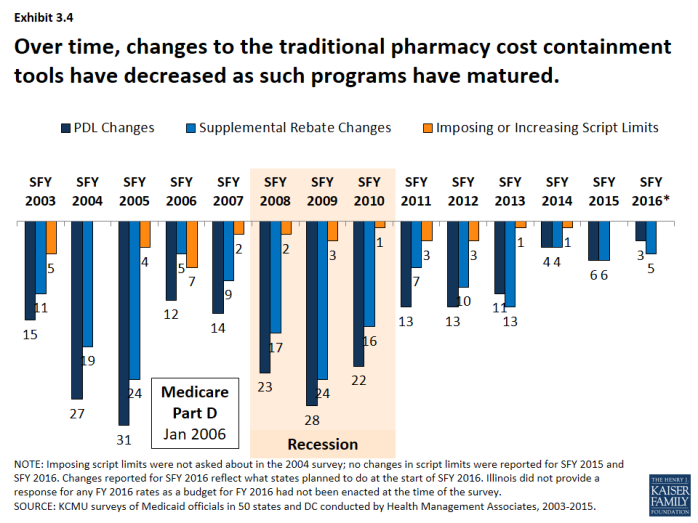

Many of the traditional pharmacy cost containment tools have been in place for a number of years. (Exhibit 3.3) The majority of states have had preferred drug lists and supplemental rebates in place since SFY 2007. Fewer states have implemented limits on the number of prescriptions. Changes to these traditional tools increased in the years leading up to the Medicare prescription drug benefit (Part D) and during the Great Recession. As Medicaid pharmacy programs have matured and the economy has improved, fewer states have made changes to these traditional tools. (Exhibit 3.4)

Long Term Care

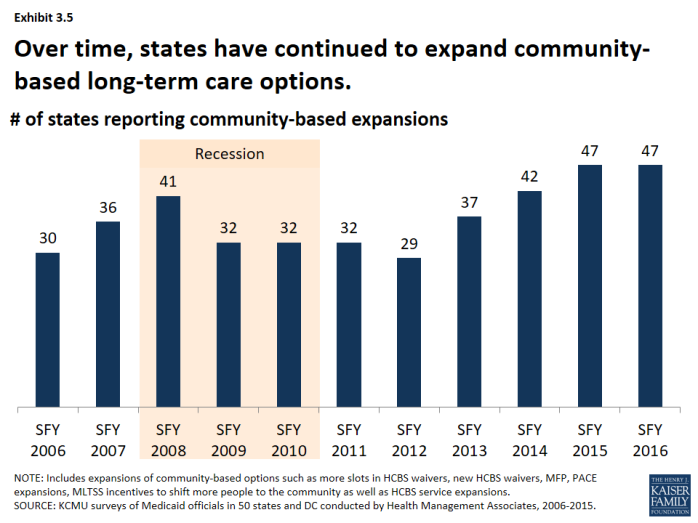

States have steadily expanded community-based long-term care options over time. Each year over the past decade, more than half of states have reported HCBS expansions to serve more people in the community. The number of states reporting HCBS expansions increased leading up to the Great Recession and declined slightly during the Great Recession and immediately afterward. As economic conditions improved, the number of states reporting community-based expansions has increased; nearly all states reported expansions in SFY 2015 and planned such action for SFY 2016. (Exhibit 3.5)

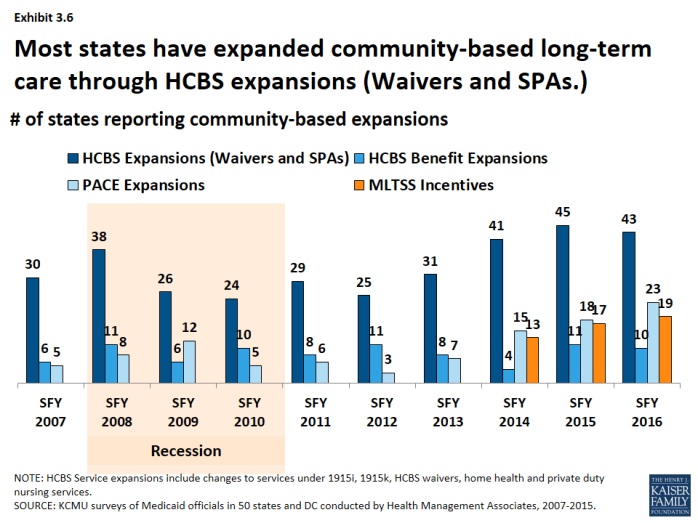

- The most common policy action to expand the number of people served in the community was through HCBS waivers and state plan amendments (SPA). (Exhibit 3.6) Examples include expanding the number of slots available in existing 1915(c) waivers, establishing new waivers, reducing waiting lists. In recent years, states have also expanded the number of people served through 1915(i) SPAs. States have also used PACE3 expansions as a tool to expand the number served in the community; state PACE activity has picked up in recent years.

- More states are building balancing incentives into managed care contracts as states increasingly adopt MLTSS. (Exhibit 3.6) The number of states with managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) programs has increased in recent years. By 2012, nearly a third of states operated an MLTSS program.4 As part of MLTSS contracts, states have increasingly built into their MLTSS programs with an expectation of increasing beneficiary access to HCBS in lieu of institutional care.

- A few states each year have also expanded the services available under HCBS waivers and through HCBS-related state plan benefits. (Exhibit 3.6) In addition to serving more people in the community, states can expand the services offered under HCBS waivers or enhance or add state plan services such as personal care, home health and private duty nursing. While not an area of intense activity, a few states each year have added or expanded these services.5

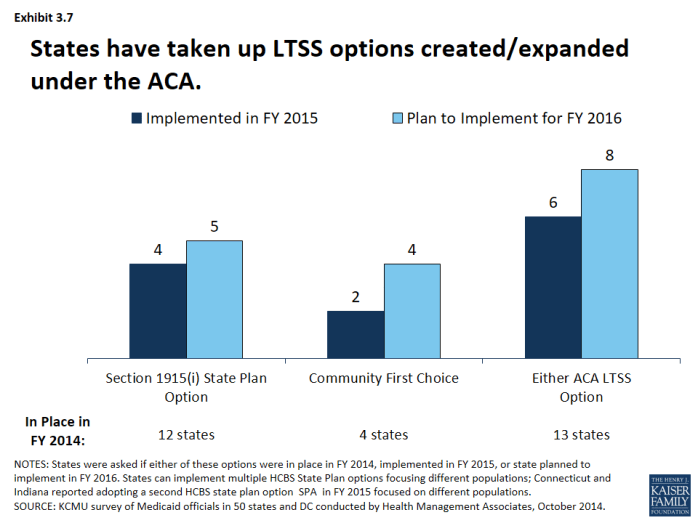

States have also been taking advantage of options created or expanded by the ACA. (Exhibit 3.7) In addition to the major coverage expansions, the ACA created and expanded states with additional options to expand the number of beneficiaries served in the community. These include the 1915(i) SPA, as described earlier, was expanded and altered by the ACA as well as the Balancing Incentives Program (BIP) and the Community First Choice (CFC) option.

- HCBS State Plan. Twelve states had at least 1 1915(i) SPA in place in SFY 2014 while 4 states (including 2 states that already had implemented a 1915(i) SPA) reported adopting a 1915(i) SPA in SFY 2015. An additional 5 states reported plans to add a 1915(i) SPA in SFY 2016.6

- Balancing Incentives Program (BIP). As of October 2015, 21 states had applications approved under the program.7 The program expired in September 2015.

- Community First Choices (CFC). Four states had adopted the CFC option in SFY 2014; 2 states adopted the option in SFY 2015. Four states reported plans to adopt the option in SFY 2016.8

| ACA LTSS Options |

| HCBS State Plan (1915(i)). This option allows states to offer HCBS through a Medicaid SPA rather than through a Section 1915(c) waiver. As a result of changes made in the ACA, income eligibility for this option was extended up to 300 percent of the maximum SSI federal benefit rate and states were permitted to target benefits to specific populations and offer the same range of HCBS under Section 1915(i) as are available under Section 1915(c) waivers. Unlike Section 1915(c) waivers, however, states are not permitted to cap enrollment or maintain a waiting list and, if offered, the benefit must be available statewide. If enrollment exceeds the state’s projections, the state may tighten their Section 1915(i) needs-based eligibility criteria, subject to advance notice and grandfathering of existing beneficiaries. = Balancing Incentives Program. Beginning in October 2011, BIP made enhanced Medicaid matching funds available to certain states that meet requirements for expanding the share of LTSS spending for HCBS (and reducing the share of LTSS spending for institutional services). Funding was available through September 2015. To qualify, states must have devoted less than 50 percent of their LTSS spending to HCBS in FFY 2009, develop a “no wrong door/single entry point” system for all LTSS, create conflict-free case management services, and develop core standardized assessment instruments to determine eligibility for non-institutionally based LTSS. = Community First Choices (1915(k)). Beginning in October 2011, states electing this state plan option to provide Medicaid-funded home and community-based attendant services and supports will receive an FMAP increase of six percentage points for CFC services. However, the final federal rule implementing this option was not released by CMS until May 2012, inhibiting state take-up of this option prior to FY 2013. |