Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2020: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Medicaid/CHIP Eligibility

Medicaid and CHIP eligibility has evolved over time to provide a comprehensive base of coverage for low-income children, pregnant women, parents, and adults. Leading up to and following the creation of the CHIP in 1997, coverage for children and pregnant women expanded through federal eligibility expansions and state take-up of options to increase coverage for these groups. However, Medicaid eligibility for parents lagged behind. In 2009, the year before passage of the ACA, the median Medicaid eligibility level for working parents was below the poverty level (64% FPL). Moreover, prior to the ACA, states could not use federal Medicaid funds to cover adults without dependent children who did not qualify through a disability- or age-based pathway. As such, adults without dependent children were largely ineligible except in a handful of states with waivers that offered limited benefits and often capped enrollment. The CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA) provided states additional options to expand coverage for children and pregnant women. Then, the enactment of the ACA in 2010 newly allowed states to receive federal Medicaid funds to cover adults without dependent children without a waiver and, as of 2014, provided enhanced federal matching funds for this coverage. As enacted, the ACA expanded Medicaid to nearly all adults with incomes at or below 138% FPL across states effective 2014. However, the 2012 Supreme Court ruling on the ACA effectively made the expansion a state option. Beyond the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income adults, states have options available under federal rules to increase Medicaid eligibility above the federal minimum income limit of 138% FPL, at regular state match.

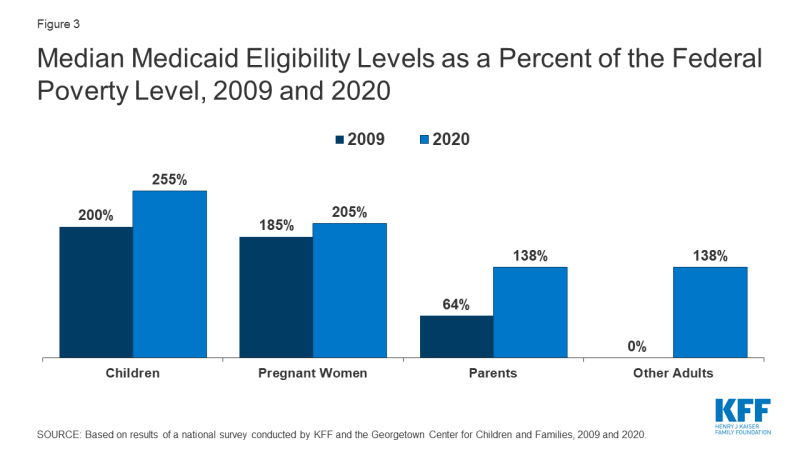

Over the past decade, median income eligibility levels significantly increased for parents and other adults, reflecting adoption of the ACA expansion. Median eligibility levels for children and pregnant women also rose over the period as states continued to take up of options to expand coverage for these groups. Specifically, the median Medicaid eligibility level for parents rose from 64% FPL in December 2009 to 138% FPL as of January 2020, while the median eligibility level for other adults increased from 0% FPL to 138% FPL. The median Medicaid/CHIP eligibility levels for children and pregnant women rose from 200% FPL to 255% FPL and from 185% FPL to 205% FPL, respectively, over the period. Despite the increases in eligibility for parents and other adults, eligibility levels for children and pregnant women remain higher than levels for parents and other adults (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Median Medicaid Eligibility Levels as a Percent of the Federal Poverty Level, 2009 and 2020

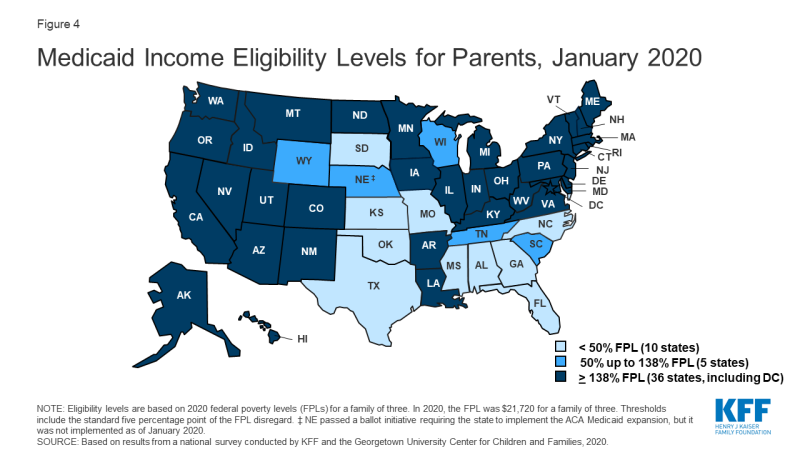

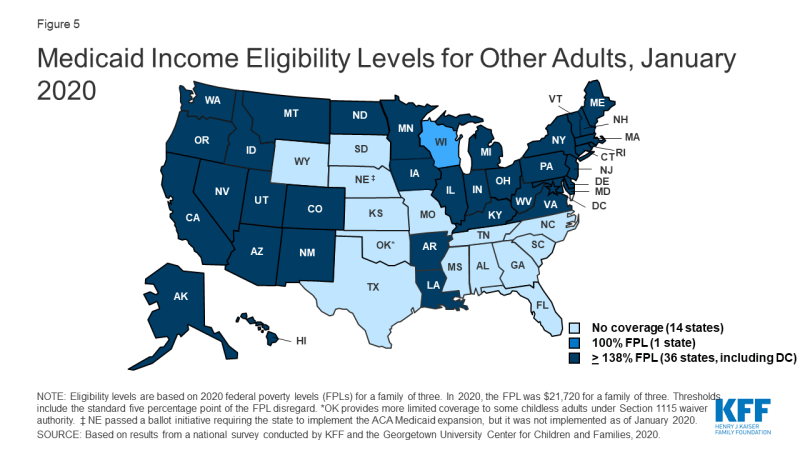

In 2019, two additional states (Idaho and Utah) implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion, bringing the total to 36 states that extend eligibility to low-income adults with incomes up to at least 138% federal poverty level (FPL, $29,974 for a family of three) as of January 2020 (Figures 4 and 5). In 2019, Connecticut raised Medicaid eligibility for parents to 160% FPL. DC also covers parents and other adults above the minimum threshold, at 221% FPL and 215% FPL, respectively.

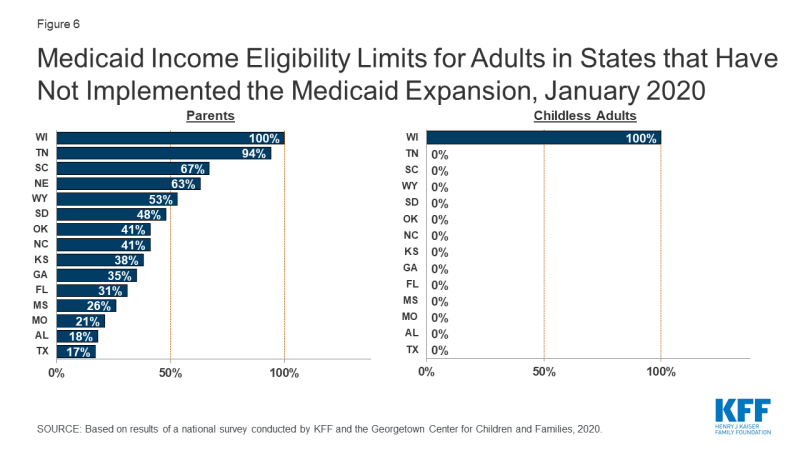

Eligibility for parents and other adults remains very limited in the 15 states that have not implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion. In non-expansion states, the median eligibility level for parents is just 41% of the FPL ($8,905 for a family of three as of January 2020), and, with the exception of Wisconsin, other adults are not eligible regardless of their income level (Figure 6). Moreover, the median eligibility level for parents in non-expansion states declined from 49% FPL to 41% FPL between 2019 and 2020. This erosion largely reflects the fact that ten non-expansion states base parent eligibility on a fixed dollar amount that states do not update on routine basis. As a result, the FPL equivalency declines over time as federal poverty levels adjust annually to account for inflation.

Figure 6: Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults in States that Have Not Implemented the Medicaid Expansion, January 2020

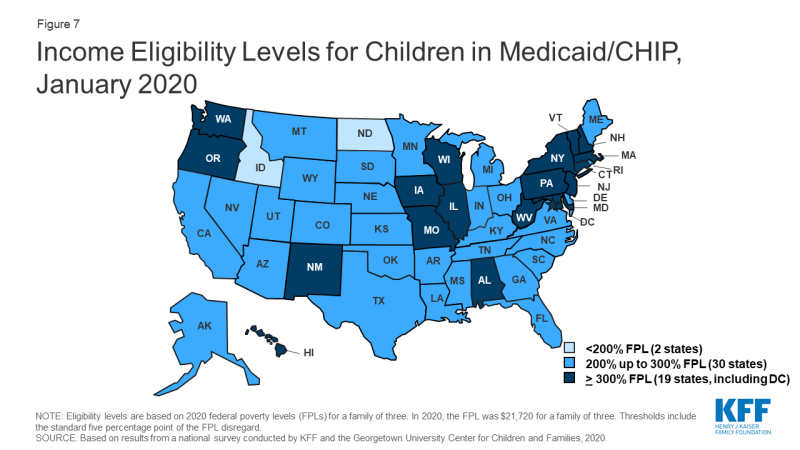

As of January 2020, nearly all states (49) cover children with family incomes up to at least 200% FPL through Medicaid and CHIP (Figure 7). Nineteen states cover children with family incomes at or above 300% FPL. However, eligibility levels vary widely across states, ranging from 175% FPL in North Dakota to 405% in New York.

Over time, states have increasingly integrated their Medicaid and CHIP programs. States can operate their CHIP program as a Medicaid expansion program, as a separate CHIP program, or use a combination of both approaches. In 2019, North Dakota eliminated its separate CHIP program and moved all children covered by CHIP into a Medicaid expansion program. With this change, 16 states administer their CHIP programs solely as extensions of Medicaid. CHIP coverage provided through Medicaid covers full Medicaid benefits, including EPSDT, and is subject to all Medicaid rules and protections. Operating CHIP as a Medicaid expansion makes the coverage between the two programs seamless for families and may be more administratively efficient for states since it eliminates the need to operate two distinct programs. Over the past decade, three other states (CA, MI, and NH) transitioned their separate CHIP programs into Medicaid.

As of January 2020, 35 states operate a separate CHIP program (alone or in combination with a CHIP Medicaid expansion). States have some flexibility over how they operate separate CHIP programs that is not available in Medicaid. For example, they can require children to be uninsured for a certain period before they can enroll in CHIP. As of January 2020, 13 of the 35 separate CHIP programs had a waiting period for children, which the ACA limited to no more than 90 days. Two states (ND and KS) eliminated CHIP waiting periods as of January 2020, continuing a trend of states removing waiting periods over the past decade. In December 2009, 35 of the 39 states with separate CHIP programs had waiting periods, 13 of which were 6 months or longer.1

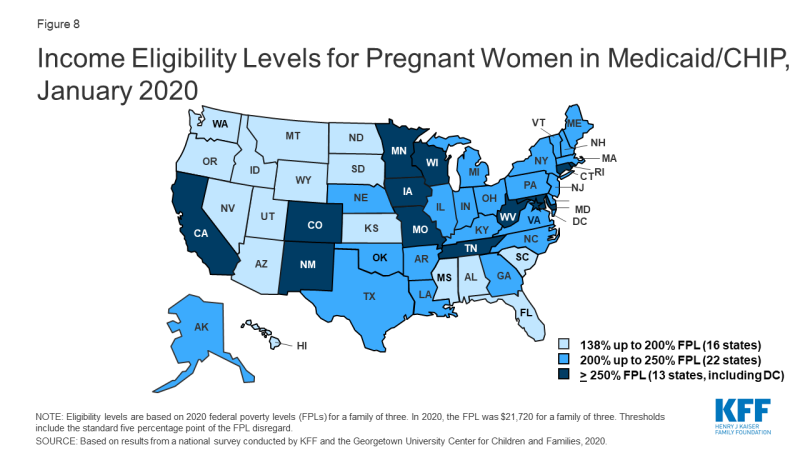

In 2019, two states increased Medicaid/CHIP eligibility for pregnant women, and the median eligibility level for pregnant women remained stable at 205% FPL. North Dakota raised its eligibility Medicaid eligibility limit for pregnant women to 162% FPL, while West Virginia expanded eligibility to 305% FPL through CHIP. As of January 2020, nearly all states (49 states) extend eligibility for pregnant women beyond the federal minimum of 138% FPL. A total of 35 states extend eligibility to at least 200% FPL, including 12 states that cover pregnant women above 250% FPL (Figure 8). However, eligibility varies from a low of 138% FPL in Idaho and South Dakota to a high of 380% FPL in Iowa.

Nine states reported plans to extend the postpartum eligibility period for pregnant women. In response to increasing rates of maternal mortality and severe morbidity, some states and federal legislative proposals are seeking to extend the length of the postpartum Medicaid eligibility period.2 Under current Medicaid rules, pregnancy-related coverage extends through 60 days postpartum. Because Medicaid/CHIP eligibility levels for pregnant women are higher than eligibility levels for parents in most states, women may lose Medicaid coverage at the end of the 60-day postpartum period. This risk of coverage loss is particularly high in states that have not implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion, where eligibility for parents remains very low. As of January 2020, nine states reported plans to extend the Medicaid postpartum eligibility period. Additional states may have pending legislative activity. Most of the nine states that reported activity were in the early planning stages. However, Illinois, Missouri, and New Jersey have developed Section 1115 waiver proposals to extend postpartum coverage, which vary in the length of extension and scope of pregnant women who would receive extended coverage. South Carolina received waiver approval in 2019 to extend postpartum coverage for a limited number of women with substance use disorder (SUD) and/or serious mental illness (SMI). California plans to use state-only funds to implement 12-month postpartum coverage for women with a documented mental health condition during pregnancy beginning July 1, 2020.

As of January 2020, New Jersey became the 29th states to offer family planning services using federal funds. The median eligibility level for family planning services is 205% FPL, but eligibility levels range from 138% in Louisiana and Oklahoma to a high of 306% FPL in Wisconsin. Two states limit eligibility for family planning services to individuals who have lost Medicaid coverage through another eligibility pathway.

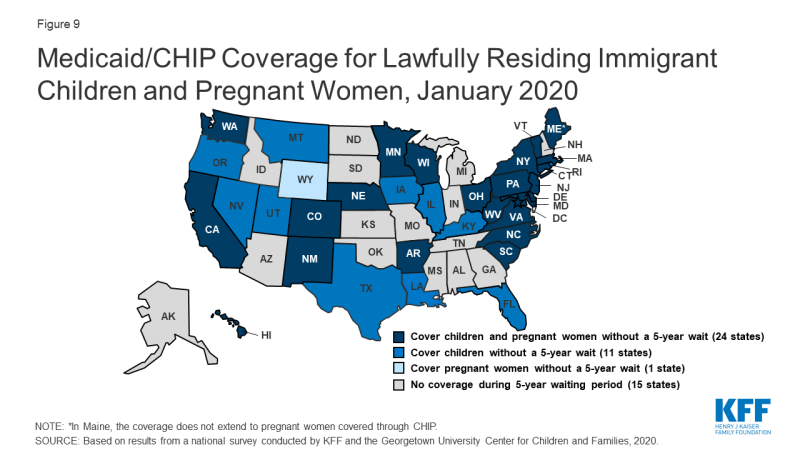

A total of 35 states have eliminated the five-year waiting period for Medicaid/CHIP coverage for lawfully residing immigrant children and/or pregnant women (Figure 9). Lawfully residing immigrants may qualify for Medicaid and CHIP but are subject to eligibility restrictions that require many to wait five years before they may enroll even when they meet all other eligibility requirements. CHIPRA provided states an option to eliminate the five-year wait for lawfully residing immigrant children and pregnant women. Nearly half (24) of states apply the option to both children and pregnant women, while 11 states use it for children only, and one state (WY) uses it only for pregnant women. This count reflects Louisiana’s adoption of the option for children in Medicaid and CHIP in 2019 and West Virginia’s expansion of the option to pregnant women covered under CHIP up to 305% FPL. Since 2002, states also have had the option to provide prenatal care to women regardless of immigration status by extending CHIP coverage to the unborn child, which 17 states provided as of January 2020. Some states have state-funded programs that cover certain groups of immigrants that do not qualify for Medicaid or CHIP.