Key State Policy Choices About Medical Frailty Determinations for Medicaid Expansion Adults

Introduction

Since 2006, states have had to determine “medical frailty” for Medicaid enrollees if states choose to design an “alternative benefit plan” (ABP) that differs from the traditional state plan benefit package. To date, there are 12 states that must determine medical frailty because they offer an ABP for Medicaid expansion adults. The medical frailty determination is intended to protect coverage for enrollees who have physical and/or mental health needs but do not qualify for Medicaid based on a disability. Federal law provides that Medicaid enrollees who are medically frail or otherwise have special medical needs must have access to the traditional state plan benefit package. Federal regulations set out the general criteria that define medical frailty (Box 1). States have flexibility to further define the specific criteria and establish the process by which medical frailty is determined, with resulting variation among states.

Medical frailty determinations are assuming greater importance in recent years as more states adopt restrictive Section 1115 waiver policies, such as premiums or work requirements. Many of these waivers apply restrictive policies to – and require medical frailty determinations for – Medicaid expansion adults, although Indiana’s waiver includes traditional low-income parents as well as expansion adults. CMS has required many, but not all, states with waivers imposing restrictions on coverage and benefits to identify and exempt enrollees who are medically frail. For example, unlike the other states discussed in this brief, Utah and Wisconsin’s waiver approvals require those states to exempt enrollees with disabilities but do not require medical frailty determinations.

This issue brief answers three key questions about medical frailty determinations and presents new data on the rules and processes used by the 12 states making these determinations for Medicaid expansion adults. All 12 states offer a benefit package to expansion adults that differs from the state plan benefit package. Additionally, six of these states have waivers that impose other restrictions on non-medically frail expansion adults. The findings are excerpted from a survey of the 50 states and the District of Columbia about Medicaid eligibility for seniors and people with disabilities conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured in fall 2018.1 Tables contain data for the 12 states.

Box 1: Federal Medical Frailty Criteria for Adults2

Federal rules require that medically frail adults include at least individuals with:

- Disabling mental disorders, including serious mental illness;

- Chronic substance use disorders;

- Serious and complex medical conditions;

- Physical, intellectual or developmental disabilities that significantly impair the ability to perform one or more activities of daily living; or

- A disability determination based on Social Security Administration criteria.

Key Questions

1. What is Medical Frailty and What are the Federal Rules?

Since 2006, states have had the option to design an “alternative benefit plan” (ABP) for certain Medicaid populations that differs from the traditional state plan benefit package.3 An ABP is a set of covered services that is either (1) based on one of three types of commercial insurance plans or their actuarial equivalent (known as the ABP benchmark) or (2) determined appropriate by the Health and Human Services Secretary. States can design ABPs targeted to different subpopulations, such as beneficiaries in different geographic areas or beneficiaries with particular medical needs.

Few states elected the ABP option prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), but ABPs became more widespread after the ACA required states to provide an ABP to Medicaid expansion adults. Expansion adult ABPs must include certain services (Box 2).4 However, an expansion adult ABP may not include all of the services in the traditional state plan benefit package,5 unless the state intentionally designs the ABP to align with the state plan benefit package.6 States can choose to design an expansion adult ABP that contains the same benefits as the state plan benefit package by using “Secretary-approved coverage” as the ABP benchmark. “Secretary-approved coverage” encompasses any Medicaid state plan benefit, including home and community-based services (HCBS).7 To fully align the benefits in an ABP with those in the Medicaid state plan benefit package, states must determine which state plan benefits must be added to the ABP and which ABP benefits must be added to the state plan benefit package.

Box 2: Benefits That the Medicaid Expansion Adult ABP Must Include:

- The ACA’s 10 categories of essential health benefits;8

- Any other benefits in the ABP benchmark plan;

- Early Periodic Screening Diagnostic & Treatment services for enrollees up to age 21;9

- Family planning services and supplies;10

- Federally qualified health center and rural health center services;11

- Emergency and non-emergency transportation;12 and

- Parity in physical and behavioral health services.13

If states do not choose to align their expansion adult ABP with the state plan benefit package, there are certain key areas that may differ, and these differences may be important to enrollees with physical or mental health needs (Box 3). The ABP may be less likely to include home and community-based services (HCBS), such as personal care services, because ABPs usually are based on commercial insurance plans, which typically provide less coverage of HCBS than what is available through the Medicaid state plan benefit package.14 On the other hand, the state plan benefit package may not include behavioral health and/or preventive services to the same extent as the expansion adult ABP because those benefits are optional in the state plan benefit package, while ABPs are subject to mental health parity and essential health benefit requirements to cover such services.15

Box 3: Key Benefits That May Differ If State Does Not Align the Expansion Adult ABP with the State Plan Benefit Package:

- Home and community-based services, such as personal care

- Behavioral health services, including mental health and substance use disorder treatment

- Preventive services

States also must identify enrollees who are medically frail if the state has a Section 1115 waiver that imposes eligibility or benefit restrictions on enrollees. The increase in these restrictive waiver policies has meant that medical frailty determinations are assuming even greater importance for enrollees’ ability to retain the coverage and scope of benefits for which they are eligible. The types of restrictions imposed under waivers from which medically frail enrollees are exempt include premiums, work and reporting requirements, limits on or elimination of non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT), mandatory enrollment in Marketplace premium assistance, required completion of a health risk assessment and healthy behavior activity, and a three-month coverage lock-out for failure to timely renew eligibility.

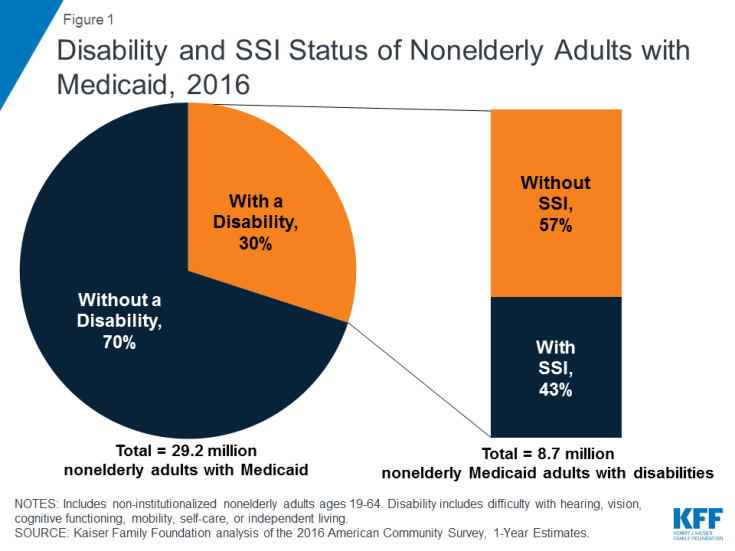

The medical frailty process accounts for the fact that the ACA expansion group includes some people with disabilities. Non-elderly adults with disabilities can qualify for Medicaid in the ACA expansion group, based solely on their low income, in states that have adopted the expansion.18 Three in 10 nonelderly adults with Medicaid report having a disability, according to data from the American Community Survey (ACS) (Figure 1). The ACS and other federal survey data classify a person as having a disability if they have a functional limitation that results in a participation limitation. This includes people who report serious difficulty with hearing, vision, cognitive functioning (concentrating, remembering, or making decisions), mobility (walking or climbing stairs), self-care (dressing or bathing), or independent living (doing errands, such as visiting a doctor’s office or shopping, alone).19

Notably, over half of nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities do not receive federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits, despite reporting serious difficulty in at least one ACS functional area (Figure 1). While receiving SSI benefits is a pathway to Medicaid eligibility for some people with disabilities, the SSI disability standard is more stringent than the ACS definition.20 In addition, SSI financial eligibility criteria are more restrictive than those for Medicaid expansion adults and other disability-related Medicaid coverage pathways.21 As a result, people with disabilities who do not receive SSI can be eligible for Medicaid as expansion adults or low-income parents22 or through an optional disability-related pathway.23 People who are eligible for Medicaid based on their status as an SSI beneficiary are excluded from coverage in the ACA expansion group.

2. Which States Must Identify Medically Frail Enrollees and What are the Implications?

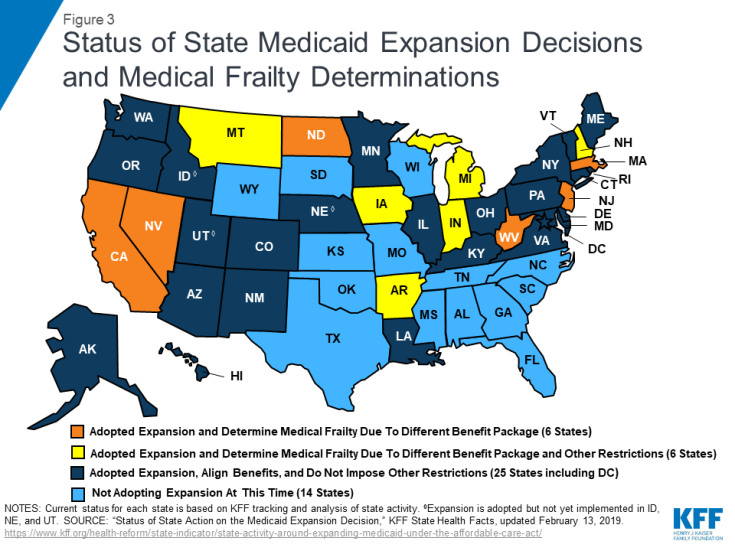

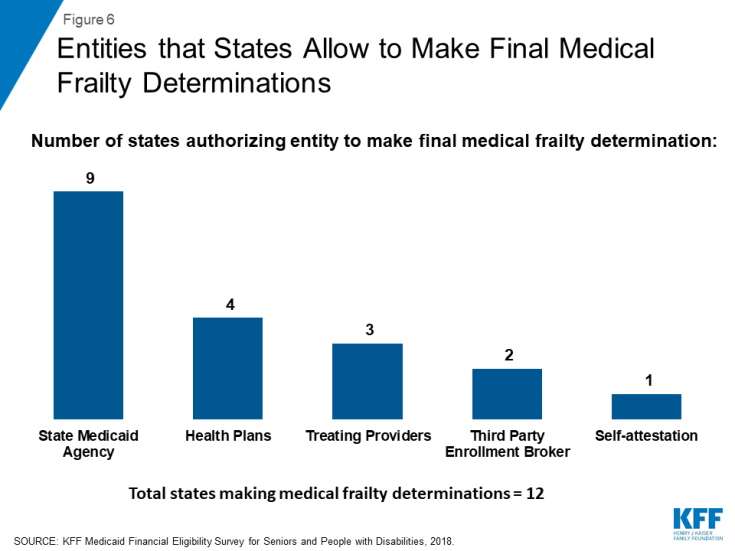

A dozen states, or about one-third of Medicaid expansion states, must identify enrollees who are medically frail because these states provide a benefit package to expansion adults that differs from the traditional state plan benefit package (Figure 2).24 As noted above, enrollees who are medically frail cannot be required to receive the expansion adult ABP and instead must have access to the state plan benefit package if they choose. The 12 states that report making medical frailty determinations because their expansion adult ABP is not aligned with their state plan benefit package include Arkansas, California, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Dakota, and West Virginia (Figure 3).

Figure 2: State Choices About Whether to Align Expansion Adult Benefit Package with State Plan Benefit Package, 2018

In addition to providing a different benefit package to expansion adults, six states impose other eligibility or benefit restrictions on Section 1115 waiver enrollees that require these states to identify and exempt medically frail individuals. These states include Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Montana, and New Hampshire (Figure 3).25 Medically frail enrollees are exempt from Section 1115 waiver provisions that impose premiums in four states (IN, IA, MI, MT) and work and reporting requirements in three states (IN, MI, and NH). They also are exempt from restrictions on NEMT in two states (AR26 and IN27), mandatory enrollment in Marketplace premium assistance in Arkansas, required completion of a health risk assessment and healthy behavior activity in Michigan, and a three-month coverage lockout for failure to timely renew eligibility in Indiana.28

States with restrictive waivers, where medical frailty determines exemptions from conditions on coverage such as work requirements and premiums, report higher shares of medically frail enrollees than states where medical frailty only determines benefit package contents. Indiana reported the highest share of expansion adults (24%) identified as medically frail in 2018, among the 7 of 12 states able to report this data (Table 1).29 In Indiana, health plans identify individuals as potentially medically frail and then make a determination using a standardized assessment tool. Eight percent of expansion adults were identified as medically frail in Arkansas and Montana. Other data show that an increasing share of Arkansas enrollees who were subject to work and reporting requirements were identified as medically frail, and therefore exempt from complying, as the requirements were implemented in 2018. In these states, medical frailty determines exemptions from coverage restrictions, including work requirements and NEMT restrictions in Indiana and Arkansas, premiums in Indiana and Montana, and mandatory Marketplace premium assistance in Arkansas (Table 1).

Other states reported much smaller shares of medically frail expansion adults, ranging from 3% in Iowa to less than 1% in New Jersey and North Dakota (Table 1). In most states reporting very low shares of medically frail enrollees, medical frailty is limited to determining benefit package contents (MA, NJ, and ND). Various factors may account for differing shares of medically frail adults among states, including enrollee knowledge and ease of navigating the process, whether multiple or few entities can identify medically frail enrollees, the type of verification required, and whether states apply relatively broad or restrictive criteria in the context of the general federal rules.

| Table 1: Share of Expansion Adults Identified as Medically Frail and Implications, 2018 | ||

| State | Share of Expansion Adults Identified as Medically Frail | Implications of Medical Frailty Determination |

| Expansion States with Section 1115 Waivers Restricting Eligibility and/or Benefits | ||

| Arkansas | 8% | Determines benefit package contents, as well as exemptions from work requirements, NEMT restrictions, and mandatory Marketplace premium assistance. |

| Indiana | 24% | Determines benefit package contents, as well as exemptions from work requirements, NEMT restrictions, and premiums. |

| Iowa | 3% | Determines benefit package contents as well as exemption from premiums. |

| Michigan | NR | Determines benefit package contents, as well as exemptions from work requirements, premiums, and mandatory health risk assessment and healthy behavior activities. |

| Montana | 8% | Determines benefit package contents, as well as exemption from premiums. |

| New Hampshire | NR | Determines benefit package contents, as well as exemptions from work requirements. |

| Expansion States without Section 1115 Waivers Restricting Eligibility and/or Benefits | ||

| California | NR | Determines benefit package contents. |

| Massachusetts | 1.40% | Determines benefit package contents. |

| Nevada | NR | Determines benefit package contents. |

| New Jersey | 0.30% 1 | Determines benefit package contents. |

| North Dakota | 0.02% | Determines benefit package contents. |

| West Virginia | NR | Determines benefit package contents. |

| NOTES: NR = No response. NEMT = non-emergency medical transportation. 1 New Jersey reported 1,698 people identified as medically frail. KFF analysis of Medicaid Budget and Expenditure System (MBES) data determined expansion adult population in FY2017 as 580,200 adults. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Financial Eligibility Survey for Seniors and People with Disabilities, 2018. |

||

3. How Do States Administer the Medical Frailty Process?

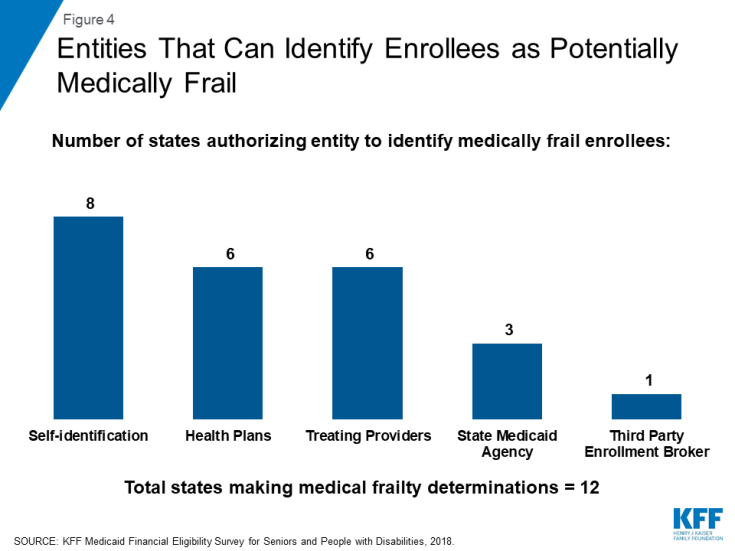

In a minority of states with medical frailty determinations, the Medicaid enrollee cannot initiate the medical frailty process (Appendix Table). These states include California, Indiana, Nevada, and New Jersey. Most states do allow the enrollee to self-identify as potentially medically frail (Figure 4). Other entities that states allow to identify enrollees as potentially medically frail include health plans, treating providers, the state Medicaid agency, and a third party enrollment broker.

Half of the states that determine medical frailty authorize just one entity to identify enrollees as potentially medically frail, which could lead to gaps in identifying eligible enrollees (Appendix Table). Four states (AR, MA, NH, and WV) allow self-identification as the only way to initiate the medical frailty determination. Self-identification is a person-centered approach but also requires that individuals know what the medical frailty designation means and how to navigate the process in order for self-identification to be a successful means of identifying eligible individuals. Navigating the process may be particularly challenging for certain enrollees. In an early look at implementation of Arkansas’ work and reporting requirements, some interviewees expressed concern about enrollees’ ability to understand that they potentially might qualify for a medical frailty exemption and to successfully navigate that process, especially for those with mental health needs. Indiana and New Jersey authorize health plans as the sole entity to initiate a medical frailty determination. Basing determinations exclusively on claims data could result in delayed identification of people who are newly enrolling in coverage or for whom there is no claims history, such as mental health or substance uses disorder services. By contrast, three states (MI, MT, and ND) allow multiple entities to initiate the medical frailty determination. Allowing multiple entities to identify enrollees as potentially medically frail may help ensure that eligible enrollees are identified.

Most states allow medically frail enrollees to be identified at multiple points, including at the time of application, at renewal, and during the eligibility period (Appendix Table). Allowing the medical frailty determination to occur at more than one time is another policy that may help ensure that all eligible individuals are identified.

Half of the states determine medical frailty based on a specific diagnosis as well as functional need criteria.30 These states include California, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Nevada, and North Dakota. By contrast, Arkansas and New Jersey only use functional need criteria. Montana and West Virginia do not require a specific diagnosis but instead base medical frailty determinations on the existence of any physical, mental, or emotional health condition that limits activities (MI) or that results in the need for assistance (WV). West Virginia also considers chronic substance abuse or developmental conditions when determining medical frailty. Massachusetts adopts the federal medical frailty criteria described in Box 1 above.31 Four states (AR, IN, NJ, and ND) use a standardized assessment tool to determine medical frailty. Standardized tools can help ensure that individuals with similar conditions are treated similarly but must be broad enough to include all enrollees who should qualify without arbitrary exclusions.

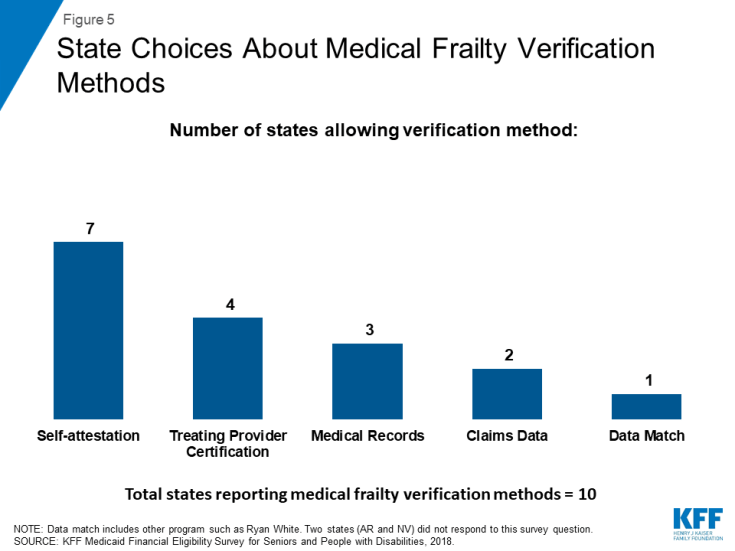

Over half of the states32 allow individuals to self-attest that they meet medical frailty criteria, instead of requiring documentation or other verification (Figure 5 and Appendix Table). Other sources of verification include treating provider certification, medical records, claims data, and data match with another program such as Ryan White. An existing body of research shows that additional reporting or administrative burdens can create barriers to eligible people retaining coverage. Half of the states provide for just one verification method, while the other six states allow more than one method.

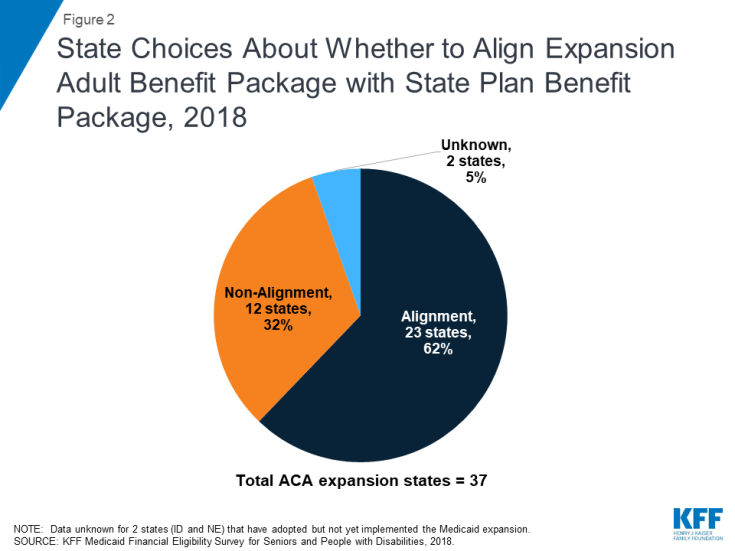

The state Medicaid agency makes the final medical frailty determination in most states (Figure 6 and Appendix Table). Other entities that states allow to make final medical frailty determinations are health plans, treating providers, and third party enrollment brokers. Individuals whose medical frailty status is denied or terminated can appeal that decision by requesting a state fair hearing in most states. In Indiana, an enrollee’s initial appeal of a medical frailty determination goes through the health plan appeals process before proceeding to a state fair hearing. Two states (NH and WV) report that a formal appeals process is not applicable because they accept enrollee self-attestation to establish medical frailty.33

Half of the states require medical frailty status to be renewed annually. These states include Arkansas, Indiana, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, and New Jersey. It is important that enrollees know about and are able to successfully navigate the medical frailty renewal process so that eligible individuals remain connected to coverage and the appropriate benefit package. The other six states review medical frailty status based on service need or a change in circumstances.

Looking Ahead

State rules and processes vary among states, and the complexity of the process can affect the extent to which Medicaid enrollees are appropriately identified as medically frail and therefore retain access to the benefit package and coverage for which they are eligible. The medical frailty process recognizes that not all people with physical and mental health needs are eligible for Medicaid based on a disability and is intended to ensure that these enrollees can access the benefit package that best meets their needs. However, if enrollees do not understand and have difficulty navigating the process, medical frailty determinations will not protect enrollees as intended. Medical frailty determinations are assuming even greater importance with the increase in Section 1115 waivers that place additional restrictions on eligibility and benefits but exempt medically frail enrollees. Policy developments in this area and assessments of whether state medical frailty criteria and procedures are appropriately identifying all eligible individuals will be important areas to continue to watch as Medicaid expansion and state implementation of restrictive waiver policies continues.