Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Screening and Counseling Services in Clinical Settings

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV), defined as sexual violence, stalking, physical violence, and psychological aggression perpetrated by an intimate partner, affects nearly a third of all Americans at some point in their lives. Although IPV affects men and women of all ages, women, particularly young women and women of color experience IPV at higher rates. An estimated 6.5 million women in the U.S. experience contact sexual violence, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner in a single year. People who are victimized by their partners are more likely to experience health problems and both the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) have identified IPV has a significant public health issue in the US. Evidence supports the role that clinicians have in assisting women who have experienced IPV and reducing adverse outcomes. The USPSTF and the Women Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) sponsored by Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) both recommend that clinicians screen women for violence. As a result, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) required private plans and Medicaid expansion programs to reimburse clinicians when they provide IPV screening and brief intervention services to women as part of their preventive care, at no additional cost to women. This factsheet reviews the prevalence and consequences of IPV and discusses insurance coverage of and access to IPV screening, counseling, and referral services for women in the US.

| Table 1: Key Terms and Definitions | |

| Term | Definition |

| Intimate Partner | A romantic or sexual partner and includes spouses, boyfriends, girlfriends, people with whom they dated, were seeing, or “hooked up.” |

| Contact Sexual Violence | A combined measure that includes rape, being made to penetrate someone else, sexual coercion, and unwanted sexual contact. |

| Stalking | Involves a pattern of harassing or threatening tactics used by a perpetrator that is both unwanted and causes fear or safety concerns in the victim. |

| Physical Violence | Includes a range of behaviors from slapping, pushing or shoving to severe acts that include hit with a fist or something hard, kicked, hurt by pulling hair, slammed against something, tried to hurt by choking or suffocating, beaten, burned on purpose, used a knife or gun. |

| Psychological Aggression | Includes expressive aggression (such as name calling, insulting or humiliating an intimate partner) and coercive control, which includes behaviors that are intended to monitor and control or threaten an intimate partner. |

| Reproductive Coercion | Includes forced or coerced sex, sabotage of contraception, or the forcible control of reproductive health by an abusive partner. Reproductive coercion can take the form of hiding, withholding, or destroying a partner’s contraceptives, breaking, poking holes in, or removing a condom in an attempt to promote pregnancy, and threats or acts of violence forcing a victim to have an abortion or carry a pregnancy to term. |

| SOURCE: CDC. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief, November 2018; Deshpande N, Lewis-O’Connor A, Screening for Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy, 2013; The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Committee on Health Care and Underserved Opinion: Reproductive and Sexual Coercion, February 2013. | |

Who is affected by IPV?

The term “intimate partner violence” is often used interchangeably with the term “domestic violence” (DV). IPV occurs across all demographics, but some groups experience higher rates. Most statistics on IPV incidence and prevalence are based on self-report. Many women are hesitant to report IPV for a variety of reasons, including financial dependence on a partner or fear of further abuse. Victims’ characteristics, such as cultural background, socio-economic status, or age, can also shape how they are affected by or speak about IPV. For example, IPV is especially stigmatized in Asian-Pacific Islander communities, so cultural and linguistic differences with providers can lead to lower reported numbers of violence. Therefore, published data may undercount actual incidence, but the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) is a population-based, anonymous, random digital dial phone survey and has been ongoing since 2010.

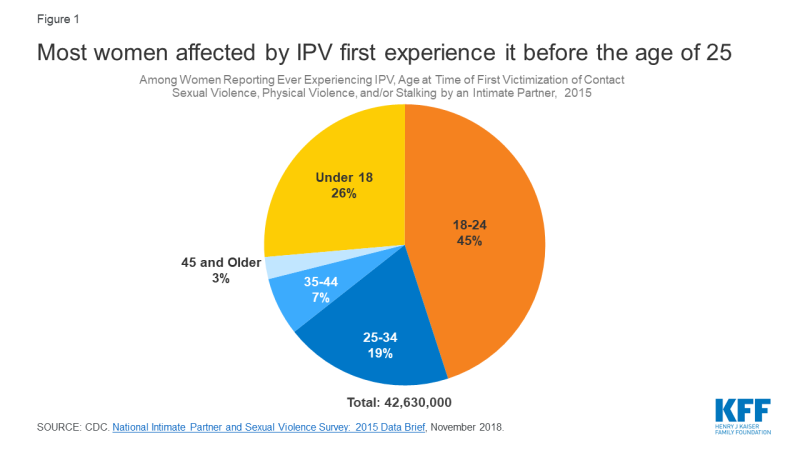

Young Women: IPV affects millions of women in the US of all ages, but nearly three quarters of all victims first experience IPV before the age of 25, with an estimated 11.6 million women experiencing their first victimization between the ages and 11 and 17 (Figure 1).

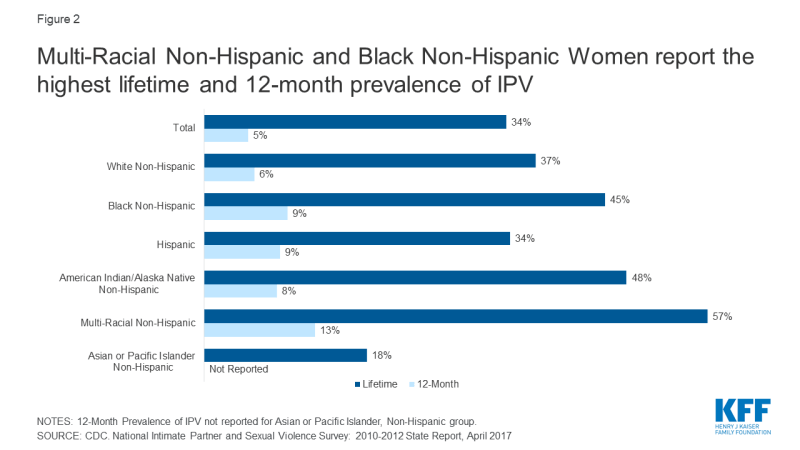

Women of color: Around half of all Non-Hispanic Black, American Indian/Alaska Native women, and Multi-Racial women have experienced IPV at some point in their lives (Figure 2). While women of all economic backgrounds can and do experience IPV, some studies show that as social class increases, risk of victimization decreases.

Figure 2: Multi-Racial Non-Hispanic and Black Non-Hispanic Women report the highest lifetime and 12-month prevalence of IPV

Women with disabilities: Women with disabilities, like women without disabilities, experience physical, sexual, and emotional violence; however, they also experience disability-specific forms (such as interference in taking medications or accessing care) of violence by an intimate partner or caretaker. In one study, women with physical health impairments were 22% more likely than women without disabilities to experience IPV; in the same study, women with mental health impairments were 67% more likely to experience IPV than their nondisabled counterparts. Overall, an estimated 26% of HIV-positive people experience IPV, but this share more than doubles to 55% amongst HIV-positive women.

LGBTQ Individuals: Four in ten (40%) of Gay/Lesbian women and six in ten (60%) Bisexual women report victimization, compared to 35% among heterosexual women.1 Studies of lifetime prevalence of IPV among transgender people range from 31% to 50%, showing similar, if not higher rates of occurrence than other sexual minorities.

Women in the military: A 2013 Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) study found a high prevalence of 12-month IPV perpetration and victimization among active duty service members, at 22% and 30% respectively. Among women Veterans, the prevalence of lifetime IPV victimization is 35%.

Women with substance Abuse Disorder: Studies have found that anywhere from 31% to 67% of women entering substance abuse treatment or methadone clinics have experienced IPV within the last year, and nearly 90% had experienced IPV within their lifetimes. Other studies have found that women who have been abused by an intimate partner are more likely to use or become dependent on substances: one study found a quarter (26%) among those experiencing IPV, compared to 5% in those who had not experienced IPV.

Pregnancy: Research has found that between 3%-9% of pregnant women are estimated to have experienced IPV during pregnancy, which can have a multitude of negative consequences for both women and babies. Pregnant women that have experienced IPV are likely to experience peri-partum depression, obstetric complications, preterm birth, low-birth weight infants, and perinatal death.2 Furthermore, research suggests that many women experience violence in the year leading up to pregnancy.3 Pregnancy offers multiple opportunities for screening and identification of IPV. Research has found that screening multiple times during the course of pregnancy results in higher identification rates than a single screen at the initial prenatal visit. A study of women who have had multiple abortions found that a history of physical or sexual abuse was associated with repeat abortion: this is also an opportunity for screening.

Reproductive coercion is a form of IPV that can include forcible control of reproductive health by an abusive partner. For example, approximately 10.3 million women have reported that an intimate partner has refused to use a condom, or tried to get them pregnant when they did not want to be pregnant.

Estimates of lifetime and 12-month exposure to IPV vary across the states, although the reasons for this variation are not well understood. Rhode Island sees the lowest percent of women experiencing contact sexual violence, physical violence, or stalking victimization by intimate partner at an estimated 4.2%, while South Carolina sees the highest, at 10.6% (Appendix Table 1). A CDC study showed that a higher prevalence of IPV was shown for women who were young, not White, unmarried, had less than 12 years of education, received Medicaid, or had unintended or stressful pregnancies. States that have a larger population of women with these characteristics are likely to see higher rates of IPV prevalence.

What are the Consequences of IPV?

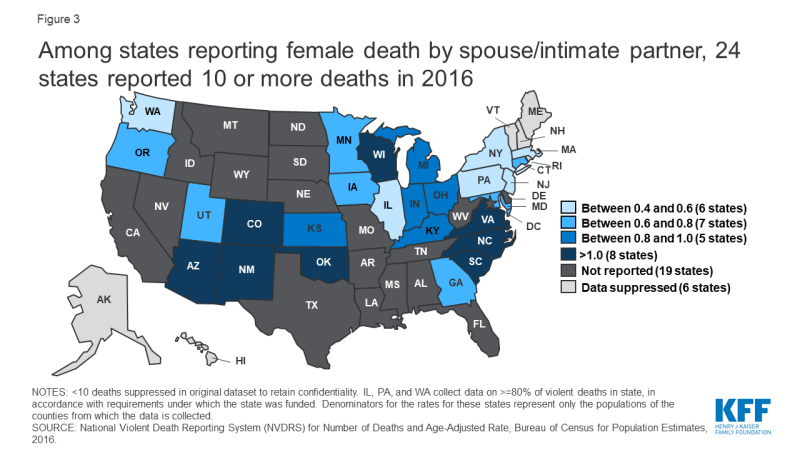

Several major medical and public health organizations, along with the CDC and USPSTF identify IPV as a significant public health issue. Four in ten (41%) of all female survivors experience physical injury related to IPV. Approximately 55% of all female homicide victims in the US are killed by an intimate partner. 31 states report their violent deaths in the Non-National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS); of those, 8 states have a rate higher than 1 death by a spouse or partner per 100,000 women: Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Among states reporting female death by spouse/intimate partner, 24 states reported 10 or more deaths in 2016

Among women who have experienced IPV in their lifetimes, 69% reported at least one IPV-related impact including safety concerns, PTSD symptoms, injury, missing work or school, needing medical care, becoming pregnant, or contracting a sexually transmitted infection. Many also reported needing assistance with housing, legal advice, and victim advocacy. Among women who experienced IPV in the past 12 months, 55% reported to have experienced one of these IPV-related impacts.4

People who have experienced IPV are more likely to report experiencing negative health outcomes, such as chronic pain, asthma, difficulty sleeping, frequent headaches, gastrointestinal disorders and increased risk of chronic conditions such as arthritis, stroke and cardiovascular disease.5 A study of Adverse Childhood Experiences found that there is a strong relationship between exposure to child maltreatment and household dysfunction (such as witnessing IPV) and many of the leading causes of death in adults: IPV not only raises health risks for the survivor, but children, who are secondary survivors.

It is estimated that the lifetime economic cost of IPV to the US population is $3.6 trillion, with a lifetime per-victim cost of $103,767 for women and $23,414 for men. This number is estimated to include medical costs, lost productivity, criminal justice costs, and other costs, such as victim property loss. Beyond the cost to the overall population, there are costs directly to the victim of IPV, such as medical care or mental health services.

Coverage for IPV Screening and Intervention

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) changed access to coverage and services to people who have experienced IPV, by both providing new protections and in requiring coverage of specific support services. Prior to the ACA, non-group health insurers could deny coverage based on pre-existing conditions, which could include conditions arising out of acts of domestic violence, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and sexually transmitted infections.6 In the years leading up to the passage of the ACA, some states did not prohibit insurance companies from considering IPV as an underwriting criterion.

Additionally, victims of IPV may also be eligible for a Special Enrollment Period (SEP) in the federal marketplace (and in state marketplaces at the state’s discretion), permitting them to enroll for coverage outside of the specified open enrollment window. The ACA requires all private plans and Medicaid expansion programs to reimburse providers when they provide the preventive services recommended by USPSTF and the WPSI, without cost-sharing for the patient.7

Research shows that the implementation of routine inquiry or screening for IPV in healthcare settings can identify those experiencing IPV and survivors of past IPV, increase access to resources, reduce abuse, and improve clinical and social outcomes.8 Both USPSTF and WPSI recommend screening women for intimate partner violence. The WPSI recommendation is broader and states that clinicians should screen adolescents and adult women of all ages for intimate partner violence annually, while the USPSTF recommendation is limited to women of reproductive age. In addition, other professional organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP),9 also recommend that providers conduct intimate partner violence screenings.

| Table 2: Recommendations for Screening of Interpersonal Violence Covered by Private Plans and Medicaid Expansion Programs | |

| Organization | Recommendation |

| U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) | The USPSTF recommends that clinicians screen for intimate partner violence (IPV) in women of reproductive age and provide or refer women who screen positive to ongoing support services. |

| Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) | The Women’s Preventive Services Initiative recommends screening adolescents and women for interpersonal and domestic violence at least annually and, when needed, providing or referring for initial intervention services. Interpersonal and domestic violence includes physical violence, sexual violence, stalking and psychological aggression (including coercion), reproductive coercion, neglect, and the threat of violence, abuse, or both. Intervention services include, but are not limited to, counseling, education, harm reduction strategies, and referral to appropriate supportive services. |

| SOURCES: USPSTF and HRSA. | |

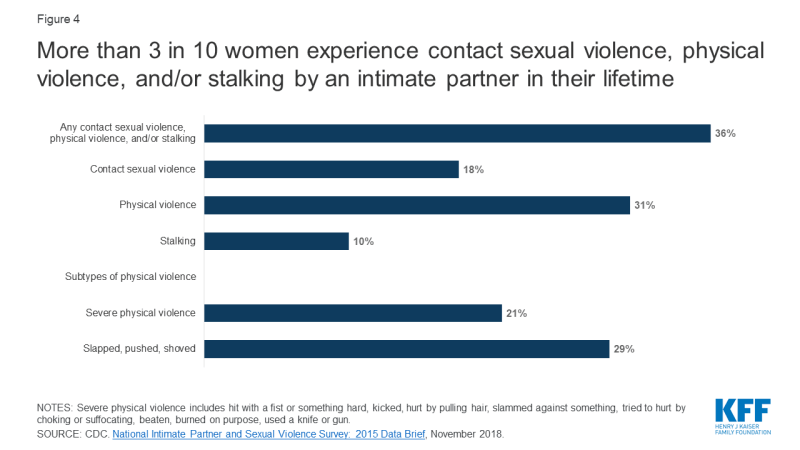

Screening

Clinicians can choose from several instruments to screen for whether a woman has experienced IPV within the last year within a primary care setting (Appendix Table 2). Most screening tools include questions about current physical violence, psychological aggression, and feeling threatened or afraid. Some cover sexual violence and stalking (Figure 4).

Figure 4: More than 3 in 10 women experience contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime

Another approach recommended by Futures Without Violence is Universal Education and Empowerment, in which clinicians talk with all patients about healthy and unhealthy relationships and the health effects of violence, and offer the opportunity for disclosure.

The ACOG recommendation outlines that IPV be screened for privately during new patient visits, annual examinations, initial prenatal visits, each trimester of pregnancy, and the postpartum checkup, while AAP (Bright Futures) recommends that IPV is discussed with mothers at prenatal, newborn, 1-month, 9-month, and 4-year visits.

Interventions and Counseling

The WPSI and USPSTF recommendations state that women who screen positive for IPV be provided or referred to ongoing support services. Most interventions include referral to mental health, social services, local and national IPV advocacy organizations, which can provide safety planning, counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other ongoing support. Other intervention resources include the brief Danger Assessment Tool (Appendix Table 3) to assess the risk for severe violence and an interactive decision aid to facilitate safety planning, myPlan, which is available as a mobile app and website.

Some of these patient resources are hotlines that the patient can call or text (Appendix Table 4). Another option is for clinicians to refer patients to their local DV advocates or mental health services.10 A systematic review of IPV interventions in primary care settings found that 76% of all interventions resulted in at least one statistically significant benefit, whether it be use of IPV resources, safety planning, improvement of health, or reductions in violence. Women receiving an intervention were found to be 60% more likely to end a relationship because it felt unhealthy or unsafe.11

What are the Challenges to Screening?

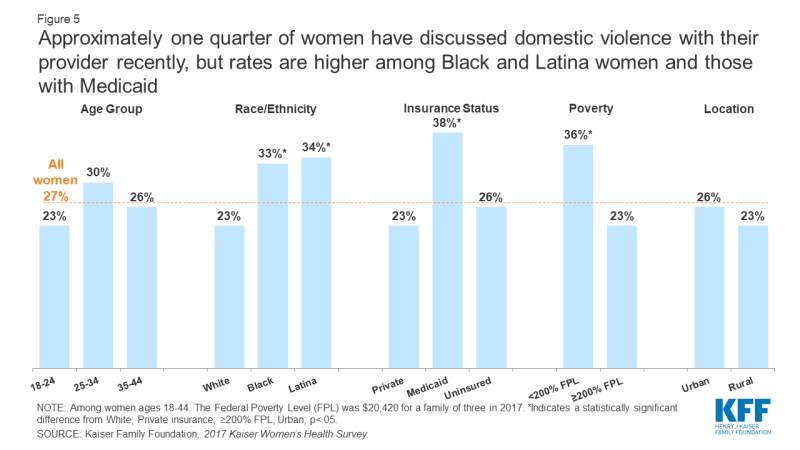

Although several years have passed since the initial recommendation for provider screening of IPV, adoption has been slow. In 2017 only 27% of women reported having discussed IPV with their provider recently (Figure 5). Low-income women, women on Medicaid, and Black or Latina women were most likely to have discussed DV than their counterparts.

Figure 5: Approximately one quarter of women have discussed domestic violence with their provider recently, but rates are higher among Black and Latina women and those with Medicaid

Ensuring privacy is one of the challenges to providers having these conversations with patients, who may not feel safe discussing IPV because their partner or someone else has accompanied them to their visit. Women who experience IPV are unlikely to disclose to a provider in front of their partner, friends, or family. To address this, clinics and providers can have a policy that patients will have at least some private time with their provider during the visit.12 The studies cited in the USPSTF recommendations only included women who could be separated from their partners at the screening phase, intervention phase, or both.

Mandatory reporting laws for IPV differs between states, but most have laws which require the reporting of specified injuries, or use of weapons. However, some clinicians feel that these reporting requirements impinge provider-patient confidentiality and may actually make patients less likely to disclose information. If a disclosure falls under a state’s reporting laws, the provider must submit an injury report to law enforcement or that state’s specified entity.13 Suspected abuse of a minor is required for reporting in all states. Futures Without Violence recommends a provider disclose their limits of confidentiality before beginning an IPV screening.

Other frequently reported barriers include personal discomfort with the issue or lack of knowledge about IPV or institutional policies. 14 Studies show that implementing a universal workflow, training, and screening protocols in an existing program might alleviate some of these barriers. 15,16,17 Some providers have reported that time constraints keep them from building patient rapport, which could lead to a positive IPV disclosure. Including nurses, nursing assistants, and other non-physician staff in screening protocols could help relieve some of the issues with time constraints.18,19

Other challenges include a fear that patients will be offended by being screened, misconception regarding a patient’s risk of IPV, or not realizing that domestic violence is a significant problem for their patient populations. 20,21 Studies have found that interdisciplinary methods of formal education, in-service training, and continuing education can assuage personal perceptions and feelings about domestic violence.22

Examples of Implementation

Despite the challenges, there are several examples of successful implementation in different settings. A systematic review of 17 programs that evaluated IPV screening found that programs that included a comprehensive approach and institutional support were effective in increasing IPV screening and disclosure rates. Effective screening protocols, initial and ongoing training, and immediate access/referrals to onsite or offsite support services helped to improve provider screening.23 Establishing provider relationships with community agencies in training sessions was found to raise the comfort level of staff, in both screening and in referring to services. Of note, HRSA is implementing a multi-year strategic framework to improve the response of health care systems to IPV.

There are multiple examples of health systems that have implemented both routine screening as well as intervention mechanisms to support, including at the Veterans Health Administration (Case Study 1: Veterans Affairs), and the not-for-profit integrated health system Kaiser Permanente (KP) (Case Study 2: Kaiser Permanente).

| Case Study 1: Veterans Affairs |

| In May 2012, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) chartered an IPV task force, which would develop a national plan for the VA to implement a trauma informed care approach. In its Plan for Implementation of the DV/IPV Assistance Program, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). These recommendations included expanding screening, prevention, and intervention services for men and women veterans, introducing an employee assistance program for those experiencing IPV, changing the language clinicians use to speak about IPV, and interventions for individuals who commit IPV. After pilot testing the plan in select sites, as of January 2019, the VHA requires all VA medical centers (VAMCs) to implement and maintain the program.

A 2019 study of 11 VAMCs found several successful clinical practices that were implemented through the program. These included the use of screening tools for primary IPV screening and secondary risk assessment, resource provision, community partnerships, and co-location of mental health resources. While VAMCs faced some of the same challenges as other providers discussed above, the study was able to identify facilitators to combat these challenges, such as engaging IPV champions. The VA Office of Research and Development is currently conducting longer studies to understand how intervention can help improve health outcomes. |

| SOURCES: Veterans Health Administration, Directive 1198: Intimate Partner Violence Assistance Program, January 2019. |

| Case Study 2: Kaiser Permanente |

| Since 2001, Kaiser Permanente Northern California,(KP) a large integrated health care organization that is not associated with KFF, has been implementing a “systems model” approach to improving screening and response to IPV and IPV identification has significantly increased. This comprehensive approach leverages the entire healthcare environment, and is comprised of five:

1) visible messaging for patients throughout the healthcare setting; As part of integrating IPV screening and intervention into clinical care settings, KP uses health information technology, including tools in the electronic health record, to support clinician inquiry, intervention, documentation, and referral as well as patient privacy. Diagnostic information does not appear on visit summaries, bills, or patient portals. Performance improvement methods using de-identified databases help sustain and guide progress across clinical departments and medical centers. |

| SOURCES: Young-Wolff KC, Kotz K, McCaw B, Transforming the Health Care Response to Intimate Partner Violence: Addressing “Wicked Problems,” June 2016. |

While earlier studies of the effectiveness of the IPV screening and intervention tended to focus on outcomes such as increased screening provided by clinicians, increased awareness of the medical facility as a resource for IPV related issues, and increased member satisfaction, there has been a recent push on studying the effects of intervention. One study interviewing women with a past or current history of IPV found that survivors placed emphasis on interventions that protected safety, privacy, and autonomy, such as interventions that did not require IPV disclosure. Another analysis of women’s perceptions of appropriate interventions also found that women were looking for nonjudgmental, nondirective, and individually tailored interventions. In both the cases of the VA and KP, there is emphasis placed on the success of interventions implemented after screening is complete.

Looking Forward

With nearly 8 million women in the US experiencing IPV annually, and nearly 45 million over the course of their lifetimes, IPV poses a significant, multi-faceted public health problem. One important component of both reducing violence and the health burdens of that violence is the role of health care providers in early detection and treatment of IPV. USPSTF and WPSI highlight studies that found lower rates of IPV in women who underwent screening and intervention.24 Furthermore, given the complex nature of IPV and the wide range of its health consequences, more providers are striving to develop IPV screening and intervention services that align with related efforts in the health care system, including providing trauma-informed care, addressing the role of social determinants of health, and improving access to mental health and addiction services.

As a result of the ACA’s preventive services coverage requirement, IPV screening is covered under most private health plans and Medicaid expansion groups. The ACA also made policy changes related to IPV, including protecting coverage access for people with pre-existing conditions and offering them special enrollment periods.

In addition to coverage, the USPSTF and WPSI recommendations imply that screening and counseling should be standard practice. As states expand Medicaid or more people become privately insured, more become eligible for coverage of these screening and counseling services, which could play an important role in reducing IPV victimization. In addition to coverage for screening, more providers are implementing interventions to connect patients to services. These efforts, along with continued education and awareness about IPV and expanded resources could improve outcomes and reduce the burden of violence experienced by millions of women in the US.

The authors thank Brigid McCaw MD, MPH, MS, FACP for her helpful review and input on this brief.