A View from the States: Key Medicaid Policy Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2019 and 2020

Executive Summary

Medicaid covers one in five Americans, accounts for one in six dollars spent on health care in the United States, and makes up more than half of all spending on long-term services and supports.1 Medicaid is a state budget driver as well as the largest source of federal revenue to states. The program is constantly evolving in response to federal policy changes, the economy, and state budget and policy priorities. As states began state fiscal year (FY) 2020, the economy in most states was strong. With fewer budget pressures, many states reported expansions or enhancements to provider rates and benefits. As several states implemented, adopted, or continued to debate the ACA Medicaid expansion, a number of states also continued to pursue work requirements and other policies promoted by the Trump administration that could restrict eligibility. Other key areas of focus highlighted in the report include Medicaid initiatives to address social determinants of health, control prescription drug spending, improve birth outcomes and reduce infant mortality, and address the opioid epidemic.

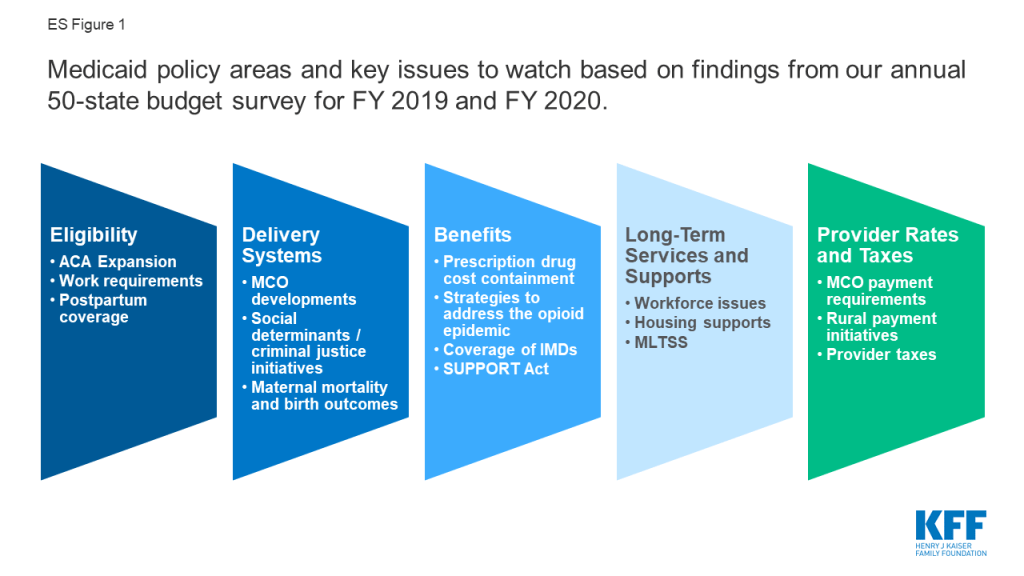

This report provides an in-depth examination of the changes taking place in Medicaid programs across the country. The findings are drawn from the 19th annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD). This report highlights certain policies in place in state Medicaid programs in FY 2019 and policy changes implemented or planned for FY 2020. The District of Columbia is counted as a state for the purposes of this report. Given differences in the financing structure of their programs, the U.S. territories were not included in this analysis. Key findings from the report are pulled from five sections: eligibility, delivery systems, benefits, long-term services and supports, and provider rates and taxes. Each section highlights key issues to watch for future policy development (ES Figure 1).

Eligibility & Premiums

Since 2014, most major eligibility policy changes have been related to adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion. Maine and Virginia implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion in FY 2019, bringing the total number of states with the expansion in place to 34 as of July 2019. Three additional states have adopted the expansion but have not yet implemented it, including Idaho which plans to implement the ACA Medicaid expansion to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) in FY 2020. Most other Medicaid eligibility expansions for FY 2019 and FY 2020 were narrow and targeted to a limited number of beneficiaries. In contrast, eligibility restrictions implemented in FY 2019 (by 7 states) or planned for implementation in FY 2020 (by 6 states) generally target broader Medicaid populations including expansion adults and parents/caretakers. All states implementing or planning eligibility policies that are counted as restrictions in FY 2019 or FY 2020 are doing so through Section 1115 waiver authority, whereas most states implementing or planning eligibility expansions are doing so through state plan authority.

What to watch:

- Medicaid expansion. Utah and Nebraska adopted the Medicaid expansion through 2018 ballot initiatives but both states are pursuing waivers to implement the expansion with program elements that differ from what is allowed under federal law, leading to implementation delays. Idaho also adopted the Medicaid expansion through a 2018 ballot initiative but submitted a Section 1332 waiver seeking to make changes to the expansion. In August 2019, CMS rejected Idaho’s waiver request; the state will implement the Medicaid expansion to 138% FPL effective January 2020. Medicaid expansion debates are active in Kansas, Missouri, and North Carolina.

- Coverage for postpartum women. In FY 2020, three states are seeking waivers to extend coverage for postpartum women beyond the current statutory requirement of 60 days after delivery.

- Work requirements. An appeal is underway in the DC Circuit after the DC federal district court stopped implementation of Arkansas’ work and reporting requirement waiver in March 2019, and prohibited Kentucky’s waiver from going into effect in April as planned. In July 2019, the DC federal district court also set aside New Hampshire’s work requirement waiver, stopping the implementation of the work requirement. Litigation challenging Indiana’s work requirements was also recently filed in the same court. Work requirement waiver requests from six non-expansion states – which may have much lower levels of eligibility based on income for parents and do not cover childless adults – are now pending. The outcomes of these requests will have implications for other states seeking to adopt similar policies.

Delivery Systems

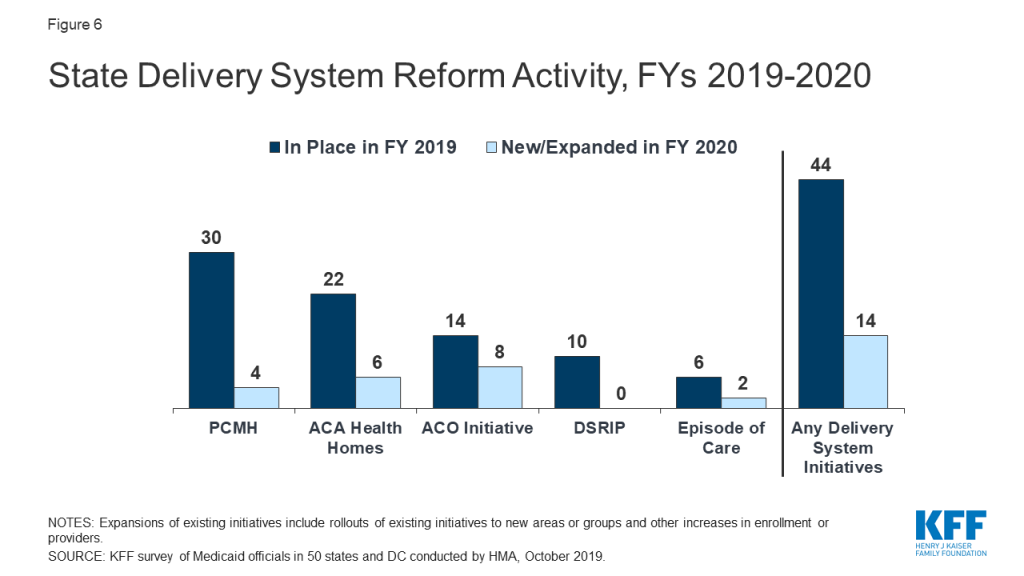

As of July 1, 2019, among the 40 states with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs), 33 states reported that 75% or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs. States continue to carve-in behavioral health services to MCO contracts and nearly all states have in place managed care quality initiatives like pay for performance or capitation withholds. Medicaid programs have been expanding their use of other service delivery and payment reform models to achieve better outcomes and lower costs. Forty-four states had one or more delivery system or payment reform initiatives in place in FY 2019 (most often patient centered medical homes or ACA Health Homes) with 14 states adding or expanding such reforms in FY 2020.

What to watch:

- MCO developments. North Carolina reported plans to implement a new MCO program in FY 2020. In FY 2019, 21 states set a target percentage of MCO provider payments or covered lives that must be in alternative payment models (APMs), three additional states plan to do so in FY 2020, and several states noted that their APM targets would increase in the future.

- Social determinants of health and criminal justice. Over three-quarters of the 41 MCO states as of FY 2020 (35 states) are leveraging MCO contracts to promote at least one strategy to address social determinants of health. Non-MCO states also report moving forward with initiatives to identify and address social determinants of health. States are also working with their MCO and corrections partners to coordinate care for justice-involved individuals prior to release with the goal of improving continuity of care and smoothing community transitions.

- Maternal mortality and birth outcomes. About two-thirds of states reported new or expanded Medicaid initiatives to improve birth outcomes and/or reduce maternal mortality in FY 2019 or FY 2020.

Benefits & Cost-Sharing

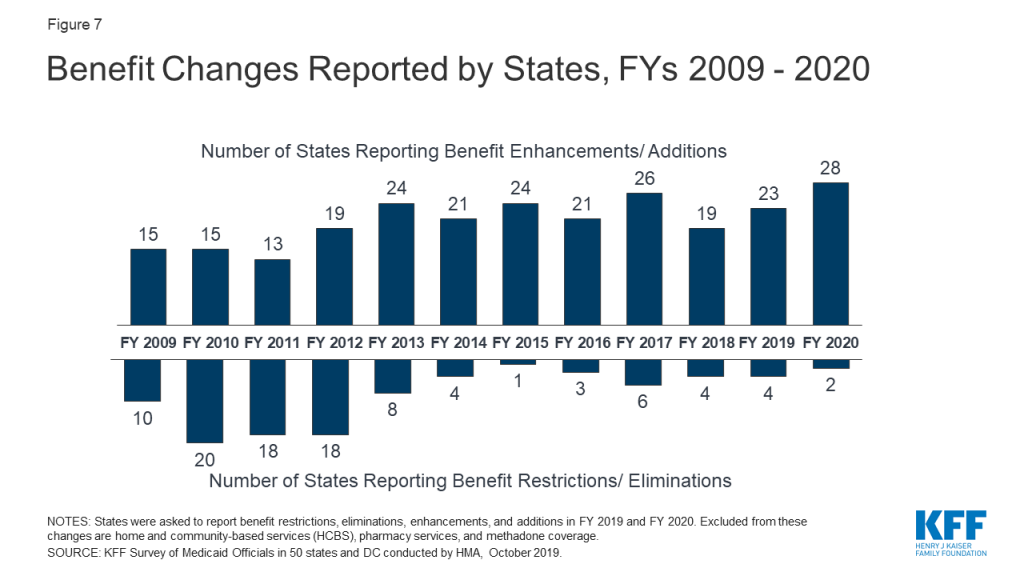

The number of states reporting benefit expansions (23 in FY 2019 and 28 in FY 2020) continues to significantly outpace the number of states reporting benefit restrictions (4 in FY 2019 and 2 in FY 2020). The most common benefit enhancements reported were for mental health/substance use disorder (SUD) services, but other service expansions include dental services, pregnancy and postpartum benefits, and diabetes prevention and care. Eleven states reported policies to eliminate or reduce a cost-sharing requirement for FY 2019 or FY 2020, compared to five states that reported new or increased cost-sharing requirements.

What to watch:

- Prescription drug cost containment. Twenty-four states in FY 2019 and 26 states in FY 2020 reported newly implementing or expanding at least one initiative to contain prescription drug costs. Strategies cited included efforts to address pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) transparency and the impact of spread pricing in managed care and implementation of new purchasing arrangements, including value-based contracts linking pharmacy reimbursement to patient outcomes. Some states reported unique models, including a modified subscription model for hepatitis C drugs in Louisiana and a drug spending cap in New York.

- Strategies to address the opioid epidemic. All states reported using pharmacy benefit management strategies (such as adoption of opioid prescribing guidelines prospective drug utilization review, prior authorization based on clinical criteria/step therapy, retrospective drug utilization review and state prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMP)) to prevent opioid-related harms. States also reported a variety of initiatives to expand access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT), including removing or relaxing prior authorization for MAT drugs.

- Institutions for Mental Disease (IMDs). In an effort to address the opioid epidemic as well as broader behavioral health issues, CMS and Congress have provided states additional flexibility to provide services in settings that would otherwise qualify as “institutions for mental disease,” or IMDs, and thus be ineligible for federal Medicaid funding. A large majority of states (43 states) reported they plan to use at least one of the flexibilities (MCO “in lieu of authority, Section 1115 waiver authority, or The Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities [SUPPORT Act] state plan option) to provide services in IMDs in FY 2020.

- SUPPORT Act. States are implementing new SUPPORT Act requirements including pharmacy benefit management strategies to reduce prescription opioid abuse and misuse and providing coverage for all FDA approved MAT drugs. Some states are also pursuing options such as enhanced matching funds for implementation of PDMPs or coverage of residential pediatric recovery centers (RPRC) for services provided to infants under age one with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and their families.

Long-Term Services and Supports

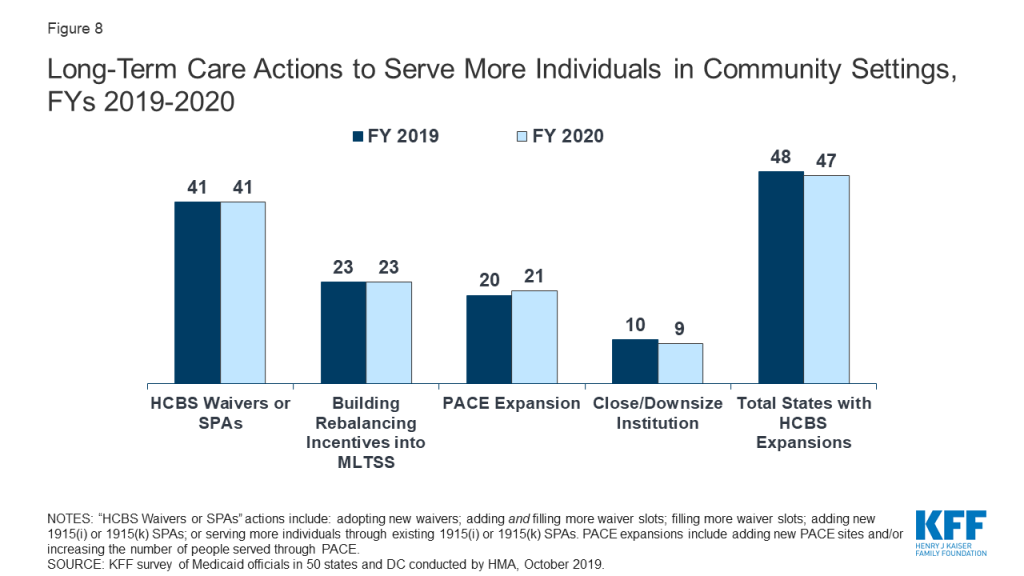

Nearly all states in FY 2019 (48 states) and in FY 2020 (47 states) are employing one or more strategies to expand the number of people served in home and community-based settings. Of these states, the vast majority report using home and community-based services (HCBS) waivers and/or state plan options (i.e., 1915(c), Section 1115, 1915(i), and 1915(k)) to serve more individuals in the community. As of July 1, 2019, 25 states covered LTSS through one or more capitated managed care arrangements, and another two states operated managed fee-for-service LTSS models.

What to watch:

- Workforce issues. States continue to work to address challenges finding and retaining LTSS direct care workers. Roughly half of states reported raising wages for direct care workers in FY 2019 and FY 2020, a notable increase from prior years. In addition, 15 states had direct care workforce development strategies (e.g., recruiting, training, credentialing) in place in FY 2019, and 10 states reported expanding (7 states) or implementing new workforce development strategies (3 states) in FY 2020.

- Housing supports. Housing supports remain an important component of state LTSS rebalancing efforts. Thirty-seven states offer housing-related supports, such as community transition services, case management, or transitional supports as part of their HCBS and Section 1115 waiver programs. States were set to phase out their Money Follows the Person (MFP) programs in federal FY 2020, but Congress provided additional funding for a short-term extension of the program; however, the uncertain future of MFP may place some of the initiatives funded through MFP at risk.

- Managed Long-Term Services and Supports (MLTSS). Several states will expand their MLTSS programs in FY 2019 and FY 2020. Pennsylvania is positioned to complete its statewide expansion of MLTSS in FY 2020, and several other states (Idaho, Illinois, and Tennessee) reported geographic or population expansions for FY 2020.

Provider Rates and Taxes

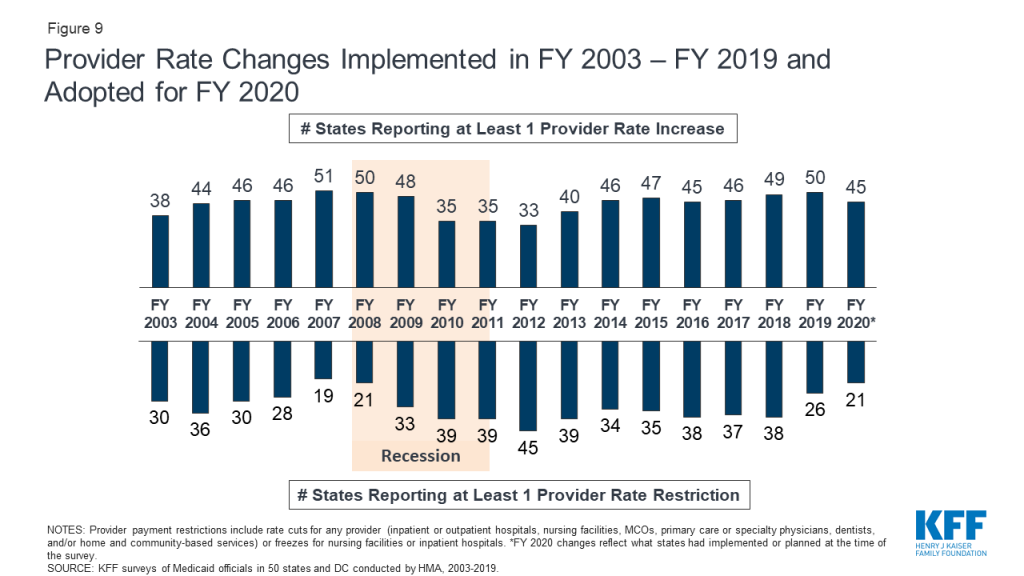

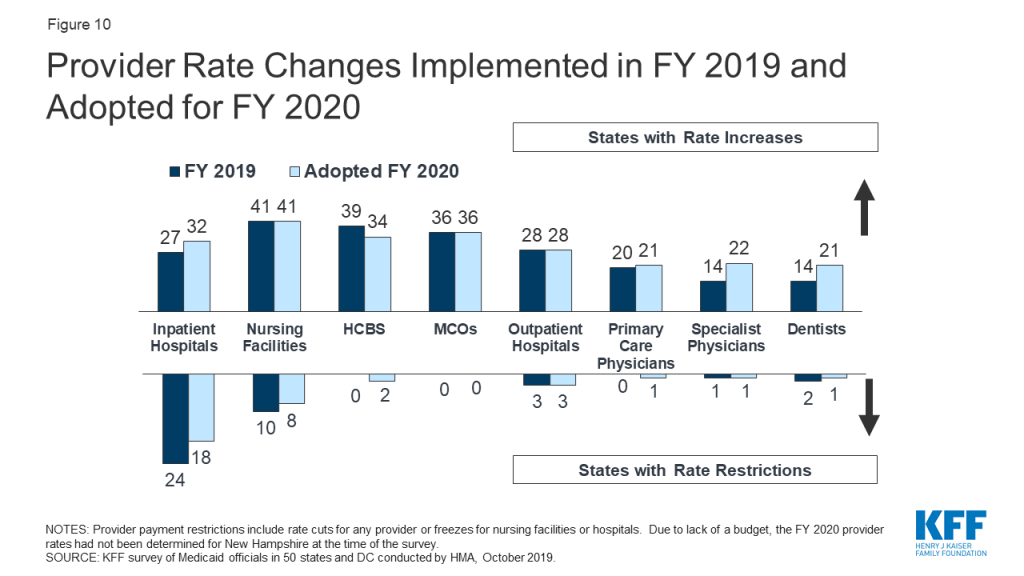

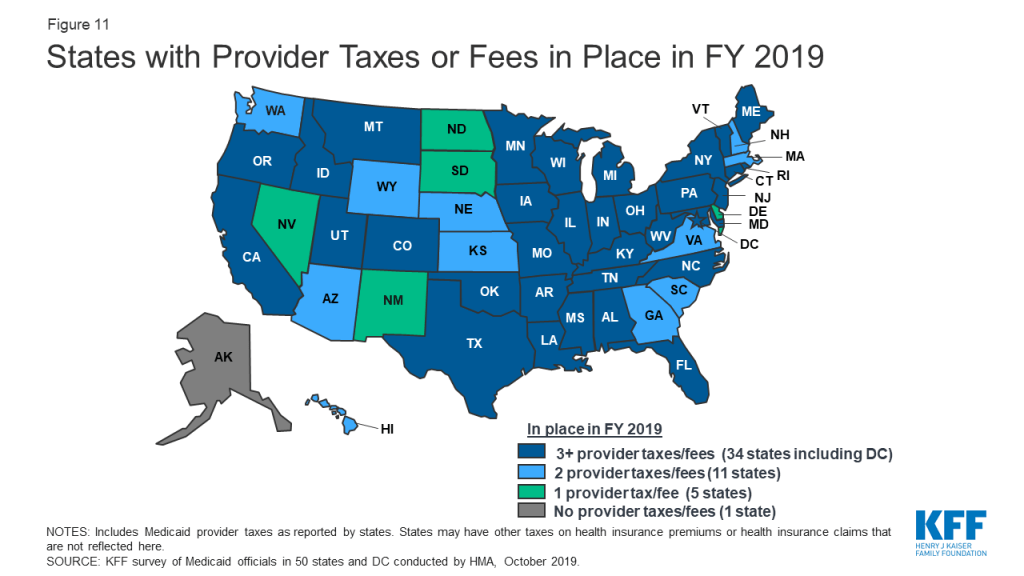

A strong economy and state revenue growth allowed most states to implement and plan more fee-for-service (FFS) provider rate increases for FY 2019 (50 states) and FY 2020 (45 states). This holds true across all major provider types. As more states increasingly rely on capitated managed care, however, FFS rate changes are a less meaningful measure of provider payment unless the state establishes MCO payment requirements. Nearly half of MCO states reported doing so: 19 states reported mandating minimum provider reimbursement rates in their MCO contracts for inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, or primary care physicians and 17 states reported requiring MCOs to change provider payment rates in accordance with FFS payment rate changes for one or more of these provider types. As in prior years, all states except Alaska rely on provider taxes and fees to fund a portion of the non-federal share of the costs of Medicaid. Six states indicate plans for new provider taxes in FY 2020.

What to watch:

- Rural payment initiatives. About half of states reported at least one policy related to payment adjustments in place to promote access to rural hospitals or other rural providers.

- Provider taxes. With the addition of California in FY 2019, eight states reported that they have a provider tax on ground emergency medical transportation, or on ambulance providers.

Looking Ahead

While national attention on health care is focused on broader debates involving prescription drug pricing and the presidential candidates’ health plans, states continue to administer and make changes to Medicaid programs, adapting to state budget and policy priorities as well as new federal Medicaid options. When asked about key priorities for state Medicaid programs, over half of states reported that delivery system and payment reforms are a key priority. A number of states also pointed to developing and implementing demonstration waivers as well as controlling Medicaid costs as key areas of focus. States are also pursuing a broad range of policies to help address increased Medicaid demands associated with an aging population.

When asked about potential for Medicaid block grant waivers, only a limited number of states expressed interest in such an option, particularly since CMS guidance on such policies has not been released. When asked about potential challenges or opportunities related to federal or state-level coverage expansions such as Medicare-for-All, few states had assessed the implications for state Medicaid programs of these broader health reforms. At the time of the survey, litigation challenging the ACA was pending before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit that could have complex and far-reaching consequences for Medicaid and the entire health care system if the ACA is overturned. Looking ahead, the trajectory of the economy, the direction of federal policies around Section 1115 Medicaid waivers, and the focus of the debate and attention to health care issues in the lead up to the November 2020 elections will also be factors that continue to shape Medicaid in FY 2020 and beyond.

Acknowledgements

Pulling together this report is a substantial effort, and the final product represents contributions from many people. The combined analytic team from the Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Management Associates (HMA) would like to thank the Medicaid directors and Medicaid staff in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. In a time of limited resources and challenging workloads, we truly appreciate the time and effort provided by these dedicated public servants to complete the survey, to participate in structured interviews, and to respond to our follow-up questions. Their work made this report possible. We also thank the leadership and staff at the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD) for their collaboration on this survey. We offer special thanks to Jim McEvoy at HMA who developed and managed the survey database and whose work is invaluable to us.

Introduction

Medicaid provides health insurance coverage to one in five Americans and accounts for nearly one-sixth of all U.S. health care expenditures.2 The Medicaid program constantly evolves due to changes in federal and state policies, the economy, and other state budget and policy priorities, and has become a significant driver of innovation in the broader health care sector. Unlike 2018 when only two states had not enacted a budget as of July 1, seven states in 2019 did not have a fully completed budget at the beginning of their fiscal year. Budget impasses, however, were driven by various policy disagreements rather than by a weak fiscal environment.3 ,4 In fact, strong revenue performance in the spring of 2019 enabled most states to finalize their FY 2020 budgets with increased spending for priority programs and more dollars directed to state rainy day funds at the beginning of FY 2020 when this survey was conducted.5

Report findings are drawn from the 19th annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD). (Previous reports are archived here.6 ) This year’s KFF/HMA Medicaid budget survey was conducted from June through September 2019 via a survey sent to each state Medicaid director in June 2019 and then a follow-up telephone interview. An acronym glossary and the survey instrument are included as appendices to this report.

The District of Columbia is counted as a state for the purposes of this report; the counts of state policies or policy actions that are interspersed throughout this report include survey responses from the 51 “states” (including DC). All 50 states and DC participated in the survey which typically includes completion of the survey instrument and a follow-up telephone interview discussions between July and September 2019.7 Given differences in the financing structure of their programs, the U.S. territories were not included in this analysis.

This report examines Medicaid policies in place or implemented in FY 2019, policy changes implemented at the beginning of FY 2020, and policy changes for which a definite decision has been made to implement in FY 2020 (which began for most states8 on July 1, 2019). Policies adopted for the upcoming year are occasionally delayed or not implemented for reasons related to legal, fiscal, administrative, systems, or political considerations, or due to delays in approval from CMS. Key findings of this survey, along with state-by-state tables, are included in the following sections of this report:

Eligibility And Premiums

Key Section Findings

Since 2014, most major eligibility policy changes have been related to adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion. Maine and Virginia implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion in FY 2019, bringing the total number of states with the expansion in place as of July 2019 to 34. Three additional states have adopted the expansion but not yet implemented it, including Idaho which plans to implement the expansion in FY 2020. Utah expanded coverage for most adults to 100% FPL (without enhanced ACA matching funds) in April 2019. Other Medicaid eligibility expansions for FY 2019 and FY 2020 were narrow and targeted to a limited number of beneficiaries. In contrast, eligibility restrictions implemented in FY 2019 (by 7 states) or planned for implementation in FY 2020 (in 6 states) generally target broader Medicaid populations including expansion adults and parents/caretakers. All states implementing or planning eligibility policies that are counted as restrictions in FY 2019 or FY 2020 are doing so through Section 1115 waiver authority, whereas most states implementing or planning eligibility expansions are doing so through state plan authority.

What to watch:

- Utah and Nebraska adopted the Medicaid expansion through 2018 ballot initiatives but both states are pursuing waivers to implement the expansion with program elements that differ from what is allowed under federal law, leading to implementation delays. Idaho also adopted the Medicaid expansion through a 2018 ballot initiative but submitted a Section 1332 waiver seeking to make changes to the expansion. In August 2019, CMS rejected Idaho’s waiver request; the state will implement the Medicaid expansion to 138% FPL effective January 2020.

- Medicaid expansion debates are active in Kansas, Missouri, and North Carolina.

- In FY 2020, three states are seeking waivers to extend coverage for postpartum women beyond the current 60 days after delivery and two states will increase the income eligibility limit for pregnant women.

- An appeal is underway in the DC Circuit after the DC federal district court stopped implementation of Arkansas’ work and reporting requirement waiver in March 2019, and prohibited Kentucky’s waiver from going into effect in April as planned. In July 2019, the DC federal district court also set aside New Hampshire’s work requirement waiver, stopping the implementation of the work requirement. Litigation challenging Indiana’s work requirement was also recently filed in the same court.

- The outcome of pending work requirement waiver requests from six non-expansion states – which may have much lower levels of eligibility based on income for parents and do not cover childless adults – will have implications for states seeking to adopt similar policies.

Table 1 summarizes the nature of eligibility policy changes by state in FY 2019 and FY 2020.

Changes to Eligibility Standards

Eligibility expansions

Aside from implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion in two states in FY 2019 and one additional state in FY 2020, most other eligibility expansions for FY 2019 and FY 2020 are narrow in scope. Overall, nine states implemented policy changes that expanded Medicaid eligibility in FY 2019, and 20 states plan to expand Medicaid eligibility in FY 2020. More states are pursuing eligibility expansions through State Plan Amendments (SPAs) compared to waivers in both FY 2019 and FY 2020 (Exhibit 1).

| Exhibit 1: Eligibility Expansions by Policy Authority | ||||

| FY 2019 | FY 2020 | |||

| State Plan Amendment | 7 States | CT, LA, MA, MD, ME, MO, VA | 13 States | CA, DC, ID, IA, LA, MA, MN, MO, ND, NJ, OK, WI, WV |

| Section 1115 Waiver | 2 States | IA, UT | 9 States | DE, HI, IL*, MO*, NJ*, NM*, RI, SC*, TN |

| *Indicates the Section 1115 Waiver has not yet been approved by CMS. | ||||

Two states (Maine and Virginia) implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion in FY 2019, bringing the total number of states that have implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion as of July 2019 to 34 (Figure 1). Expansion was implemented in Virginia and Maine in January 2019. Maine adopted the Medicaid expansion through a November 2017 ballot initiative. Due to delays by the former governor, however, implementation did not occur until the new governor signed an executive order in January 2019 directing the Department of Health and Human Services to begin expansion implementation and provide coverage to those eligible retroactive to July 2018. CMS approved the state’s plan retroactive to July 2, 2018.

Three states (Idaho, Nebraska and Utah) newly adopted the expansion through 2018 ballot initiatives, but implementation of the full expansion has been delayed in all three states. 9

- Utah voters approved a full ACA expansion to cover nearly all adults with income up to 138% of the FPL, however, the Utah legislature significantly changed and limited the coverage expansion that was adopted by the voters. The governor signed legislation in February 2019 that calls for multiple steps to implement an expansion of Medicaid coverage to adults in ways that differ from a full ACA expansion.10 As of October 2019, CMS had approved an amendment to Utah’s existing Section 1115 demonstration waiver to expand Medicaid to a capped number of adults with income up to 100% FPL beginning on April 1, 2019 at the state’s regular Medicaid matching rate, not the enhanced ACA matching rate. Additional waivers are pending/forthcoming per state law.11 ,12 If CMS does not approve the waivers by July 1, 2020 (the start of FY 2021), state legislation requires the state to adopt the full Medicaid expansion without restrictions as required by the ballot initiative.

- In Idaho, the governor signed a bill passed by the legislature in April 2019 that makes changes to the Medicaid expansion program approved by voters. The state submitted a Section 1332 waiver seeking permission to access the ACA enhanced match rate for the newly eligible population up to 100% FPL and for individuals between 100-138% FPL who choose to “opt-in” to Medicaid coverage. The state proposed that the default for the 100-138% FPL population would be qualified health plan (QHP) coverage in the Marketplace with advance premium tax credits. In August 2019, CMS rejected Idaho’s 1332 waiver request.13 The state will implement the Medicaid expansion to 138% FPL effective January 2020.

- Nebraska submitted an expansion SPA in April 2019 that delays implementation until October 1, 2020 (FY 2021) to allow time for the state to seek a Section 1115 waiver to implement expansion with program elements that differ from what is allowed under federal law.

In May 2019, the Montana governor signed legislation to continue the state’s Medicaid expansion program with significant changes until 2025. This action came after Montana residents voted down a measure on the November 2018 ballot that would have extended the Medicaid expansion beyond the June 30, 2019 sunset date and raised taxes on tobacco products to finance the expansion. Current legislation directs the state to seek federal waiver authority to make several changes to the existing expansion program, including adding a work requirement as a condition of eligibility and increasing the premiums required by many beneficiaries.

In a number of states, Medicaid expansion was still under debate for FY 2020 and beyond. In North Carolina, the governor vetoed the budget passed in late June 2019 primarily because it did not expand Medicaid. The budget stalemate continues as of October 2019. In September 2019, advocates in Missouri launched a campaign to put Medicaid expansion on the ballot in November 2020. To qualify for the ballot initiative, they must obtain at least 172,000 signatures. After legislation failed to pass last session in Kansas, in September 2019, the governor signed an executive order establishing a committee to study the Medicaid expansion experience in other states and to outline these findings for consideration during the 2020 legislative session.

Six states implemented more narrow eligibility expansions in FY 2019 and 19 states plan to implement more limited expansions in FY 2020. Some examples of these other expansions include the following:

- Restoring retroactive coverage. In FY 2019, Iowa reinstated retroactive eligibility for nursing facility residents. In FY 2020, Delaware and Oklahoma will restore retroactive eligibility for children and pregnant women. In FY 2020, Hawaii and New Mexico plan to reinstate retroactive eligibility for all groups.14 (The elimination of retroactive coverage requires a Section 1115 waiver.)

- Expanding coverage for pregnant and postpartum women. Three states (Illinois, Missouri, and South Carolina) are seeking waiver authority to extend coverage in FY 2020 for postpartum women beyond the current 60 days: Illinois plans to submit a Section 1115 waiver proposal to extend postpartum coverage to one year; Missouri’s proposal will specifically target women with a substance use disorder (SUD) diagnosis; South Carolina is seeking to extend coverage for pregnant women up to 199% FPL from 60 days postpartum to one-year postpartum. In addition, in FY 2020, North Dakota will increase the income limit for pregnant women from 152% FPL to 162% FPL, and West Virginia will increase the income limit for pregnant women from 150% FPL to 185% FPL.

- Covering children with disabilities/complex needs. Three states (Louisiana, Rhode Island, and Tennessee) are using either SPA or waiver authority to cover children with significant disabilities at home who would not qualify for Medicaid if the incomes and assets of their families were counted.

- Eliminating the 5-year waiting period for lawfully-residing immigrant children. In FY 2019, Louisiana eliminated the five-year waiting period for Medicaid eligibility for lawfully-residing immigrant children.

- Increasing the income limit for the parent/caretaker group and other limited groups.15 In FY 2020, if approved by CMS, South Carolina plans to increase the income limit for parent/caretakers from 67% FPL to 100% FPL. South Carolina’s pending waiver would also provide new coverage with an enrollment cap (that can be set at zero) for childless adults who are eligible due to homelessness, justice system involvement, or need for mental health or SUD treatment. The pending waiver includes a work requirement for non-exempt parent/caretakers and those in the new, capped enrollment groups.

Eligibility Restrictions

A number of states continue to pursue Section 1115 waivers which include policies that would result in eligibility restrictions in FY 2019 and FY 2020 (Exhibit 2). Policies that have or are likely to result in enrollment declines are counted as restrictions in this report. Seven states reported implementing restrictions in FY 2019 and six states reported restrictions already implemented or planned for implementation in FY 2020 (Exhibit 2 and Table 1).

Although not cited as eligibility standards changes, several states (not included in the counts below) noted a downward pressure on enrollment in FY 2019 or FY 2020 related to increased eligibility verifications, data matching, and other process-related issues.

| Exhibit 2: Eligibility Restrictions by Policy Authority | ||||

| FY 2019 | FY 2020 | |||

| State Plan Amendment | 0 States | 0 States | ||

| Section 1115 Waiver | 7 States | AR, FL, IN, KY, MA, NH, NM | 6 States | AZ, MI, MT*, UT, VA*, WI |

| *Indicates the Section 1115 Waiver has not yet been approved by CMS. | ||||

The most frequently reported eligibility restrictions implemented in FY 2019 or planned for FY 2020 are work or community engagement requirements. Work requirement waivers generally require beneficiaries to verify their participation in certain activities, such as employment, job search, or job training programs, for a certain number of hours per week or verify an exemption to receive or retain Medicaid coverage. Details about the specific number of hours, approved activities, exemptions, reporting process, and populations included (e.g., expansion adults and/or low-income parents) vary across states. Data show, however, that most Medicaid enrollees are already working or would qualify for exemptions from these requirements, yet many of these individuals would still need to navigate a reporting or exemption process to retain their Medicaid coverage.16 ,17 ,18 In this report, work requirement policies are counted based on the initial date of implementation rather than the date on which the first coverage terminations will occur.

| Exhibit 3: Work Requirement Waivers by Approval Status as of October 2019 | |

| Approved* | 6 States: AZ, IN, MI, OH, UT, WI |

| Pending+ | 9 States: AL, ID, MS, MT, OK, SC, SD, TN, VA |

| Vacated by Court^ | 3 States: AR, KY, NH |

| *AZ and OH plan to implement in FY 2021; +No non-expansion state pending work requirement waivers (AL, MS, OK, SC, SD, TN) were counted as “planned for implementation” in FY 2020 (see additional discussion below); ^AR, KY, and NH counted as eligibility restriction in FY 2019. | |

Six states currently have approved Section 1115 work requirement waivers (Exhibit 3). While Indiana began implementation of the work requirement in FY 2019 (in January 2019), no hours are required in the first 6 months. The phase-in of required hours began in months 7-9 with a requirement of 5 hours per week. Each December beneficiaries will be subject to a review of their community engagement hours for the prior 12-months. The first coverage losses are expected to take effect January 1, 2020 for beneficiaries who do not meet the required community engagement hours. (On September 23, 2019, a federal lawsuit was filed in the DC district court challenging the HHS Secretary’s approval of Indiana’s “Healthy Indiana Plan” waiver, including the approval of its work requirement (among other waiver provisions).) Michigan, Utah, and Wisconsin19 plan to implement work requirement waivers in FY 2020. Arizona and Ohio plan to implement work requirement waivers in FY 2021.

With the exception of Virginia, Montana, and Idaho, all other pending work requirement waivers are from non-expansion states. If approved, Virginia and Montana plan to implement work requirement waivers in FY 2020 and Idaho plans to implement in FY 2021.20 As of October 2019, CMS has not approved a work requirement waiver from a non-expansion state other than Wisconsin. The Wisconsin work requirement only applies to childless adults. Since there is no precedent for an approval of a work requirement waiver for parents and caretaker relatives in a non-expansion state and the timing of such an approval is unknown, this report does not count any non-expansion state pending work requirement waivers under “planned implementation” for FY 2020 (even though a few states indicated, depending on if/when approved, FY 2020 implementation may be possible).

As a result of litigation challenging work requirements, three states (Arkansas, Kentucky and New Hampshire) have had work requirement waivers set aside by the courts. On March 28, 2019, the DC federal district court set aside the HHS Secretary’s approval of Medicaid waivers with work and reporting requirements and other eligibility and enrollment restrictions in Kentucky and Arkansas.21 This was the second time the court ruled on Kentucky’s waiver, after finding that the Secretary’s initial approval was similarly flawed, and the first time the court considered Arkansas’s waiver. The court vacated both waivers – stopping work and reporting requirements as well as other waiver provisions. While Kentucky had not begun implementation, Arkansas’s waiver implementation began in June 2018 and resulted in over 18,000 people losing coverage.22 An appeal currently is underway in the DC Circuit.

On July 29, 2019, the DC federal district court set aside New Hampshire’s work requirement waiver. Implementation was stopped unless and until HHS issues a new approval that passes legal muster or prevails on appeal.23 Although the state began implementation in June 2019, no enrollees had lost coverage yet.

While several states moved to restore retroactive eligibility (described above), a few new states obtained waivers to eliminate or reduce retroactive coverage. In FY 2019, Florida eliminated retroactive coverage for non-pregnant adults. In FY 2020 (effective July 1, 2019), Arizona eliminated retroactive coverage for most newly eligible members excluding pregnant women and children. Although Maine received waiver approval (in December 2018) to eliminate retroactive eligibility, in January 2019 the incoming governor informed CMS that the state would not accept the terms of the approved waiver. Similarly, in New Mexico, a Section 1115 waiver amendment was approved in December 2018 that allowed the state to limit retroactive coverage to one month for most managed care members; however, under the new governor, the state submitted an amendment in June 2019 to reinstate the full 90-day retroactive coverage period. Finally, as a result of litigation challenging Section 1115 waivers, retroactive coverage restrictions were set aside/stopped in Arkansas, Kentucky, and New Hampshire.

Other examples of reported eligibility restrictions in FY 2019 or FY 2020 include:

- Conditioning eligibility on premium payment. In FY 2020, Virginia plans to implement (if their pending waiver is approved) premiums for non-exempt adults above 100% FPL. Coverage will be suspended for failure to pay premiums after a three-month grace period. In FY 2020, Wisconsin plans to implement premiums for childless adults from 50-100% FPL as a condition of eligibility, with disenrollment and a lock-out period for up to six months.

- Waiving reasonable promptness. In FY 2020, Virginia plans to implement (if their pending waiver is approved) a reasonable promptness waiver, delaying the start of coverage until after the first premium is paid for non-exempt enrollees above 100% FPL.

- Conditioning eligibility on completion of a health risk assessment. In FY 2020, Wisconsin will condition eligibility for childless adults on the completion of a health risk assessment.

Many states implementing Section 1115 waivers that include eligibility conditions (e.g., work requirements, coverage lockouts, and premium requirements) indicated that these policies impact administrative processes and expenses. Specific examples noted include:

- Information system costs – data matches and interfaces with other programs, creation of enrollee reporting portals, and development of automated participant notices24

- Staffing costs and contract changes – call center staff, staff or contractors for outreach and education, staff to invoice and track premiums

- MCO contract changes – requiring plans to verify exemptions, manage premium collections and reductions, etc.

Births Financed by Medicaid

Medicaid is a key source of financing of births for low- and modest-income families. Women who would not otherwise be eligible can qualify for Medicaid coverage for pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum care due to higher income eligibility thresholds for pregnant women.25 Medicaid directors were asked to provide the most recent available data on the share of all births in their states that were financed by Medicaid. About three-quarters of the 50 reporting states were able to provide data for calendar year or fiscal year 2017 or 2018. The rest of the states provided data from 2013-2016 or 2019. The median share of births financed by Medicaid in the 50 reporting states was 46%. Six states (Arkansas, Louisiana,26 Mississippi, Nevada, New Mexico, and South Carolina) reported that Medicaid pays for 60% or more of all births in their state, while four states reported that Medicaid finances less than 30% of all births (New Hampshire, North Dakota, Utah, and Vermont).

Premiums

The Medicaid statute generally does not allow states to charge premiums to most Medicaid beneficiaries. Historically, premiums were limited to special higher income categories of beneficiaries such as expanded Medicaid for working people with disabilities. However, some states have obtained waiver authority to charge higher premiums and/or copayments than otherwise allowed, especially for the Medicaid expansion population.

Four states (Iowa, Indiana, Maine, and Wisconsin) reported implementation of new premium programs or changes to existing premiums in FY 2019. In FY 2019, Indiana implemented a tobacco premium surcharge for expansion adults and low-income parent/caretakers, increasing premiums by 50% for tobacco users beginning in their second year of enrollment, as part of its Healthy Indiana Plan (“HIP”) waiver. Maine implemented premium increases in its long-standing Section 1115 waiver serving persons with HIV/AIDS. Those subject to premium amounts will see premiums increase 5% annually over the ten-year demonstration period. Effective July 1, 2018, Iowa added a new $3 per month premium for Dental Wellness Program (DWP) members that do not complete healthy behaviors. Effective January 1, 2019, Wisconsin ended premiums for parents and caretaker relatives receiving Medicaid under the Transitional Medical Assistance component of the program. New Mexico had obtained approval under a Section 1115 waiver to implement premiums for expansion adults above 100% FPL starting in 2019; however, the state, under a new governor, is amending the waiver to remove this authority and does not intend to implement premiums.

Four states (Idaho, Montana, Virginia, and Wisconsin) reported planned implementation of new premium programs or changes to existing premiums in FY 2020. Montana and Virginia have implemented or plan to implement new premiums or premium changes for Medicaid expansion adults. Montana’s pending waiver request proposes to gradually increase premiums for each year a member is enrolled in the expansion (from 2% of income for the first two years up to 4% at the rate of 0.5% per year) for expansion adults 50-138% FPL. Virginia’s pending waiver request would add premiums for expansion adults above 100% FPL. In FY 2020, Wisconsin plans to implement premiums for childless adults which will vary based on completion of a health risk assessment and healthy behaviors. Finally, Idaho is planning to implement premiums for children in its Serious Emotional Disturbance (SED) Youth Empowerment Services (“YES”) Section 1915(i) program in FY 2020.

Coverage Initiatives for the Criminal Justice Population

The Medicaid expansion provided a new coverage option for many individuals involved with the criminal justice system, especially childless adults who were not previously eligible in most states. While Medicaid cannot pay for services other than inpatient hospitalization during incarceration, most states are seeking ways to promptly provide coverage and health care services to individuals upon release. Maintenance of medications and access to behavioral health services can be important factors in mitigating recidivism rates.27

Most states reported policies already in place as of FY 2019 to suspend Medicaid eligibility for incarcerated individuals in both prisons and jails (Exhibit 4). When Medicaid eligibility is suspended (instead of terminated) when an enrollee becomes incarcerated, a simple change in status can allow for prompt reinstatement of eligibility upon release from incarceration. Six states plan to implement suspension policies for prisons and jails in FY 2020. Alabama already suspends Medicaid eligibility for individuals incarcerated in jails but plans to implement the suspension policy for prisons in FY 2020.

| Exhibit 4: Suspension of Medicaid Eligibility for Incarcerated Individuals | ||

| Prisons | Jails | |

| In place as of FY 2019 | 43 states | 42 states |

| Plan to implement in FY 2020 | AL, ID, MO, NV, OK, UT, WI | ID, MO, NV, OK, UT, WI |

| No plans to implement in FY 2019 or FY 2020 | KS | IL, KS, NC |

States were also asked if Medicaid eligibility agencies have an electronic, automated data exchange process with jails and/or prisons to facilitate suspension and reinstatement of eligibility for individuals moving into and out of incarceration. About half of states (23 states) indicated such processes were in place in FY 2019. Nine additional states indicated plans to implement an electronic, automated data exchange process in FY 2020. Seventeen states indicated there are no current plans to implement such a process.28

SUPPORT Act: Foster Care Eligibility

As of October 1, 2019, The Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (SUPPORT) Act prohibits states from terminating Medicaid eligibility for individuals under age 21 or former foster care youth up to age 26 while they are incarcerated and also requires states to redetermine eligibility for these populations prior to release without requiring a new application and to restore coverage upon release.29 States were asked to describe any challenges or issues related to coming into compliance with these requirements. About half of states indicated that they are not facing challenges related to complying with this requirement. In contrast, other states indicated that this policy presents challenges or requires significant additional steps including new process development, system changes, development of automated data exchanges, interagency communication and coordination, changes to state laws, and need for additional federal guidance.

Table 1: Changes to Eligibility Standards in all 50 States and DC, FY 2019 and FY 2020

Eligibility Standard Changes | ||||||

States | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | ||||

(+) | (-) | (#) | (+) | (-) | (#) | |

Alabama | ||||||

Alaska | ||||||

Arizona | X | |||||

Arkansas | X | * | ||||

California | X | |||||

Colorado | ||||||

Connecticut | X | |||||

Delaware | X | |||||

DC | X | X | ||||

Florida | X | |||||

Georgia | ||||||

Hawaii | X | |||||

Idaho | X | |||||

Illinois | X | |||||

Indiana | X | X | ||||

Iowa | X | X | ||||

Kansas | ||||||

Kentucky | X | * | ||||

Louisiana | X | X | ||||

Maine | X | |||||

Maryland | X | |||||

Massachusetts | X | X | X | |||

Michigan |

| X | ||||

Minnesota | X | |||||

Mississippi | ||||||

Missouri | X | X | ||||

Montana | X | |||||

Nebraska | ||||||

Nevada | ||||||

New Hampshire | X | * | ||||

New Jersey | X | |||||

New Mexico | X | X | ||||

New York | ||||||

North Carolina | ||||||

North Dakota | X | |||||

Ohio | ||||||

Oklahoma | X | |||||

Oregon | ||||||

Pennsylvania | ||||||

Rhode Island | X | |||||

South Carolina | X | |||||

South Dakota | ||||||

Tennessee | X | |||||

Texas | ||||||

Utah | X | X | X | X | ||

Vermont | ||||||

Virginia | X | X | ||||

Washington | ||||||

West Virginia | X | |||||

Wisconsin** | X | X | ||||

Wyoming | ||||||

Totals | 9 | 7 | 1 | 20 | 6 | 3 |

NOTES: From the beneficiary’s perspective, eligibility expansions or policies likely to increase Medicaid enrollment are denoted with (+), eligibility restrictions or policies likely to decrease enrollment are denoted with (-), and neutral changes are denoted with (#). This table captures eligibility changes that states have implemented or plan to implement in FY 2019 or FY 2020, including changes that are part of approved and pending Section 1115 waivers. No non-expansion state pending work requirement waivers (AL, MS, OK, SC, SD, TN) were counted as “planned for implementation” in FY 2020.*Denotes that the court set aside continued or new implementation of waiver provisions. **Wisconsin’s Section 1115 waiver covers childless adults ages 19 to 64 with income up to 100% FPL, without ACA enhanced matching funds. The state has an approved work and reporting requirement waiver for this population. The state plans to implement this provision as soon as CMS approves their implementation plan and when funding is made available for work supports. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2019. | ||||||

Delivery Systems

Key Section Findings

As of July 1, 2019, among the 40 states with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs), 33 states reported that 75% or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs. States continue to carve-in behavioral health services to MCO contracts and nearly all states have managed care quality initiatives in place such as pay for performance or capitation withholds. Medicaid programs have been expanding their use of other service delivery and payment reform models to achieve better outcomes and lower costs. Forty-four states had one or more delivery system or payment reform initiatives in place in FY 2019 (most often patient centered medical homes or ACA Health Homes) with 14 states adding or expanding delivery system reforms in FY 2020.

What to watch:

- North Carolina reported plans to implement a new MCO program in FY 2020.

- In FY 2019, 21 states set a target percentage of MCO provider payments or covered lives that must be in alternative payment models (APMs), three additional states plan to do so in FY 2020, and several states noted that their APM targets would increase in the future.

- Over three-quarters of the 41 MCO states as of FY 2020 (35 states) are leveraging MCO contracts to promote at least one strategy to address social determinants of health. Non-MCO states also report moving forward with initiatives to identify and address social determinants of health.

- States are working with their MCO and corrections partners to coordinate care for justice-involved individuals prior to release with the goal of improving continuity of care and smoothing community transitions.

- About two-thirds of states reported new or expanded Medicaid initiatives to improve birth outcomes and/or reduce maternal mortality in FY 2019 or FY 2020.

Tables 2 through 5 include more detail on the populations covered under managed care (Tables 2 and 3), behavioral health services covered under MCOs (Table 4), and managed care quality initiatives (Table 5). Table 6 contains more detailed information on emerging delivery system and payment reform initiatives in place in FY 2019 and new or expanded initiatives in FY 2020.

Managed Care

Capitated managed care remains the predominant delivery system for Medicaid in most states. As of July 2019, all states except four – Alaska, Connecticut,30 Vermont,31 and Wyoming – had some form of managed care (comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs) and/or primary care case management (PCCM)) in place. As of July 2019, 40 states were contracting with MCOs, up from 39 states last year. Twelve states reported operating a PCCM program, down two states from last year. PCCM is a managed FFS based system in which beneficiaries are enrolled with a primary care provider who is paid a small monthly fee to provide case management services in addition to primary care. For purposes of this report, states contracting with “PCCM entities”32 are also counted as offering a PCCM program.

Of the 47 states that operate some form of managed care, five operate both MCOs and a PCCM program while 35 states operate MCOs only and seven states operate PCCM programs only33 (Figure 2 and Table 2). In total, 28 states contracted with one or more limited benefit prepaid health plans (PHPs) (unchanged from 2018) to provide Medicaid benefits including, behavioral health care, dental care, vision care, non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT), or long-term services and supports (LTSS).

Populations Covered by Risk-Based Managed Care

Among the 40 states with MCOs, 33 states reported that 75% or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2019. This is unchanged from last year’s survey and includes nine of the ten states with the largest total Medicaid enrollment. These nine states (California, New York, Florida, Texas, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, and Washington) account for over half of all Medicaid beneficiaries across the country (Figure 3 and Table 2).34

Children and adults, particularly those enrolled through the ACA Medicaid expansion, are much more likely to be enrolled in an MCO than elderly Medicaid beneficiaries or persons with disabilities. Thirty-six35 of the 40 MCO states reported covering 75% or more of all children through MCOs. Of the 34 states that had implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion as of July 1, 2019, 29 were using MCOs to cover newly eligible adults.36 The large majority of these states (26 states) covered more than 75% of beneficiaries in this group through capitated managed care, including New Hampshire that ended its Section 1115 premium assistance waiver at the end of CY 2018 and transitioned its Qualified Health Plan-enrolled members to MCOs.37 Thirty-two of the 40 MCO states reported covering 75% or more of low-income adults in pre-ACA expansion groups (e.g., parents, pregnant women) through MCOs. In contrast, the elderly and people with disabilities were the group least likely to be covered through managed care contracts, with only 21 of the 40 MCO states reporting coverage of 75% or more such enrollees through MCOs (Figure 3).

Of the five states with both MCOs and PCCM programs, PCCM programs cover a larger share of beneficiaries than MCOs in three of these states. As of July 1, 2019, Arkansas’ recently implemented MCO program (described further below) covered only 5% of Medicaid beneficiaries with the rest of the Medicaid population divided between PCCM (45%) and fee-for-service (50%); over 90% of Colorado’s enrollees remained in the PCCM program, which is the foundation of the state’s “Accountable Care Collaboratives;” and North Dakota covered 44% of its Medicaid enrollees in its PCCM program compared to 23% of enrollees (all ACA expansion adults) under an MCO contract. In contrast, Massachusetts reported greater MCO enrollment (42%) compared to PCCM (26%) and Washington reported only minimal PCCM enrollment (1%) compared to MCO enrollment (93%).

Arkansas reported implementing an MCO program for the first time in FY 2019 and North Carolina reported plans to implement an MCO program for the first time in FY 2020. In March 2019, Arkansas began making actuarially sound “global payments” to “Provider-led Arkansas Shared Savings Entities” (PASSEs) that serve Medicaid beneficiaries who have complex behavioral health and intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) service needs. In FY 2020, North Carolina will launch new MCO “Standard Plans” with mandatory enrollment for most population groups (about 1.6 million enrollees). Conversely, Alaska reported that it had halted its previous plan to implement an MCO arrangement in FY 2020 to serve one geographic area (Anchorage and the Mat-Su Valley). Only one state reported a policy change that reduces the state’s reliance on the MCO model of managed care: Indiana reported that presumptively eligible members are now initially covered under FFS rather than being enrolled in MCOs.

Populations with Special Needs

For geographic areas where MCOs operate, this year’s survey asked MCO states whether, as of July 1, 2019, certain subpopulations with special needs – excluding those dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare or receiving long-term services and supports – were enrolled in MCOs for their acute care services on a mandatory or voluntary basis or were always excluded (Exhibit 5 and Table 3).

Consistent with results from past surveys, pregnant women were most likely to be enrolled on a mandatory basis while persons with I/DD were among the least likely to be enrolled on mandatory basis. As a group, seniors were most likely to be excluded (although a number of states noted that non-dual, non-LTSS seniors constitute a relatively small subpopulation). Foster children were most likely to be enrolled on a voluntary basis, although they were enrolled on a mandatory basis in a larger number of states.

| Exhibit 5: MCO Enrollment of Populations with Special Needs, July 1, 2019(# of States) | |||||||

| Non-Dual/Non-LTSS: | |||||||

| Pregnant women | Medically Fragile/ Technology Dependent Children | Foster Children | Persons with SMI/SED | Persons with I/DD | Persons w/ physical disabilities | Seniors | |

| Always mandatory | 34 | 20 | 22 | 26 | 19 | 24 | 23 |

| Always voluntary | 2 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| Varies | 3 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 5 |

| Always excluded | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 9 |

| Notes: “SMI/SED” – persons with serious mental illness or serious emotional disturbance, “I/DD” – persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. | |||||||

This year’s survey also asked MCO states to comment on their acute care MCO enrollment policies for dual eligibles and persons receiving LTSS. Because these two characteristics often overlap, all state responses could not be sorted into discrete categories. At least 11 states, however, reported that both dual eligibles and persons receiving LTSS had their Medicaid acute care services covered on a mandatory basis under an MCO arrangement (Arizona, Delaware, Hawaii, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, Tennessee, and Virginia). Conversely, nine states reported that both dual eligibles and persons receiving LTSS were always excluded from acute care MCO coverage (Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, North Dakota, Nevada, Wisconsin, and West Virginia). Also, states with Financial Alignment Initiatives for dual eligibles in addition to other managed care programs often cited varying enrollment criteria for dual eligibles.

Acute Care Managed Care Population Changes

In both FY 2019 and FY 2020, a few states reported actions to increase enrollment in acute care managed care, reflecting full or nearly full MCO saturation in most MCO states. As described above, Arkansas and North Carolina reported implementing, or plans to implement, an MCO program for the first time in FY 2019, and FY 2020, respectively. Of the 40 states with MCOs already in place as of July 1, 2019, six states in FY 2019 and eight states in FY 2020 indicated that they made specific policy changes to increase the number of enrollees in MCOs through voluntary or mandatory enrollment of new groups into MCOs, or mandatory enrollment of specific eligibility groups that were formerly enrolled on a voluntary basis (Exhibit 6). Thirty-eight states reported that acute care MCOs were operating statewide as of July 2019. The remaining two MCO states without statewide programs (Colorado and Nevada) did not report a geographic expansion planned for FY 2020.

| Exhibit 6: Medicaid Acute Care Managed Care Population Expansions, FY 2019 and FY 2020 | ||

| FY 2019 | FY 2020 | |

| Geographic Expansions | — | — |

| New Population Groups Added | DE, MS, NH, OH, PA, VA | DE, IL, NY, OH, PA, TN, WV |

| Voluntary to Mandatory Enrollment | — | NE, NY |

| Implementing an MCO program for the first time | AR | NC |

In FY 2019 and FY 2020, states expanded MCO enrollment (either voluntary or mandatory) to other groups including persons with ID/DD (Delaware and New York), special needs children, children with SED, or SSI children (Illinois, Mississippi, Tennessee), expansion adults transitioning from the state’s premium assistance program to MCO coverage (New Hampshire), children in foster care (New York and West Virginia), workers with disabilities, persons receiving Specialized Recovery Services, and persons meeting the nursing facility level of care criteria (Ohio), and persons with third party liability coverage (Virginia). Also, Pennsylvania reported the addition of full benefit dual eligibles and individuals receiving LTSS to acute care managed care by continuing the geographic phase-in of its Community HealthChoices (CHC) MCO program that combines both acute care and LTSS.

Only two states made enrollment mandatory for a specific eligibility group that was formerly enrolled on a voluntary basis: in FY 2020, Nebraska is making enrollment mandatory for refugee resettlement and state disability assistance enrollees, and New York is making enrollment mandatory for participants in its 1915(c) HCBS Children’s waiver (unless eligible for another enrollment exception).

Services Covered Under MCO Contracts

Behavioral Health Services Covered Under MCO Contracts

Although MCOs are at risk financially for providing a comprehensive set of acute care services, nearly all states exclude or “carve-out” certain services from their MCO contracts, frequently behavioral health services. States with acute care MCOs were asked to indicate whether specialty outpatient mental health (MH) services, inpatient mental health services, and outpatient and inpatient substance use disorder (SUD) services are always carved-in (i.e., virtually all services are covered by the MCO), always carved-out (to PHP or FFS), or the carve-in status varies by geographic or other factors. Consistent with results from last year’s survey, more than half of the 40 MCO states reported that specific behavioral health service types were carved into their MCO contracts, with specialty outpatient mental health services somewhat less likely to be carved in (Exhibit 7 and Table 4).

| Exhibit 7: MCO Coverage of Behavioral Health, July 1, 2019(# of States) | ||||

| Specialty Outpatient MH* | Inpatient MH | Outpatient SUD | Inpatient SUD | |

| Always carved-in | 23 | 28 | 29 | 29 |

| Always carved-out | 10 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Varies | 7 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| *“Specialty outpatient mental health” services mean services used by adults with Serious Mental Illness (SMI) and/or youth with serious emotional disturbance (SED), commonly provided by specialty providers such as community mental health centers. | ||||

Eight states in FY 2019 and nine states in FY 2020 reported changes in how behavioral health benefits are delivered under MCO contracts:

- Four states in FY 2019 (Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, and Virginia) and one state in FY 2020 (New Jersey) reported actions to carve certain behavioral health services into their MCO contracts. Ohio reported a full carve-in of behavioral health services as of July 1, 2018.

- Four other states (Kentucky, Nebraska, West Virginia, and Wisconsin) reported plans to add SUD waiver services to their MCO contracts in FY 2020. South Carolina added “in lieu of” SUD IMD (“Institutions for Mental Disease”) services to its MCO contracts in FY 2019 and other SUD services in FY 2020.

- Arizona and Washington reported implementing, or plans to implement, additional integrated MCO contracts in both FY 2019 and FY 2020.

- Mississippi added “in lieu of” free standing psychiatric hospital services to its MCO contracts in FY 2019.

- North Carolina’s “Standard” MCO plans implemented in FY 2020 will cover some behavioral health services, other than certain high intensity services that will continue to be provided by the state’s current behavioral health plans.

Managed Care (Acute and LTSS) Quality, Contract Requirements, and Administration

Quality Initiatives

Over time, the expansion of comprehensive risk-based managed care in Medicaid has been accompanied by greater attention to measuring quality and plan performance and, increasingly, to measuring health outcomes. After years of comprehensive risk-based managed care experience within the Medicaid program, states have become more sophisticated in incorporating quality metrics into the ongoing monitoring of MCOs, and many states now incorporate quality into the procurement process.38

States procure MCO contracts using different approaches; however, most states use competitive bidding, in part because the dollar value is so large. Under these procurements, states can specify requirements and criteria that go beyond price and may expect plans to compete on the basis of value-based payment arrangements with network providers, specific policy priorities such as improving birth outcomes, strategies to address social determinants of health, and/or other specific performance and quality criteria.

Nearly all MCO states (36 of 40 states) reported using at least one select Medicaid managed care quality initiative in FY 2019 (Figure 4 and Table 5). Two additional states not reporting quality initiatives in 2019 indicated that they had implemented new quality initiatives in FY 2020, bringing the total number to 38 states with at least one of these managed care quality strategies in place. States were asked to indicate whether they had specific managed care quality strategies (acute and/or MLTSS) in place in FY 2019 and to identify newly added or expanded initiatives for FY 2020. The overwhelming majority of states (34 out of 40) reported they made MCO comparison data publicly available in FY 2019. More than half of MCO states reported pay for performance incentives and/or capitation withhold arrangements in place in FY 2019. Fewer states reported use of an auto-assignment algorithm that includes quality performance measures.

In FY 2020, more than half of MCO states (23 states) expect to implement new or expanded quality initiatives (Figure 4). The majority of the actions states plan for FY 2020 represent enhancements or expansions to current quality strategies, rather than implementation of a new strategy. However, five states reported new initiatives in FY 2020. Three states reported implementing a pay for performance strategy (California, Illinois, and New Hampshire) and two states reported implementing a capitation withhold (Mississippi and New Hampshire) for the first time. Utah plans to make acute care MCO comparison data available in FY 2020 through the creation of a public-facing dashboard. Ohio reports transitioning from a pay for performance to a capitation withhold strategy in its acute care programs.39

PERFORMANCE MEASURE FOCUS AREAS

States that employed a pay for performance bonus or penalty, a capitation withhold and/or an auto-assignment quality factor (discussed above) were asked to identify performance measure focus areas linked to these quality incentives (Exhibit 8). Over three quarters of MCO states (31 states) reported using chronic disease management metrics when rewarding or penalizing plan performance. More than half of MCO states reported linking these quality initiatives to perinatal/birth outcome measures (26 states) or mental health measures (24 states). These focus areas are not surprising given the chronic physical health and behavioral health needs of the Medicaid population, as well as the significant share of the nation’s births funded by Medicaid. Over half of MCO states (22 states) tie quality incentives to potentially preventable events (PPEs) and nearly half (17 states) link incentives to value-based purchasing metrics, which is a growing area of focus for states (discussed in more detail below). Twelve states listed “other” focus areas including LTSS-related metrics (e.g., documentation of care goals and interaction with the care team in a dual eligible Financial Alignment Initiative (California)) and HCBS rebalancing (Hawaii). Other states reported incentives or penalties linked to operational metrics such as claims processing timelines and submission of encounter data.

| Exhibit 8: Performance Measure Focus Areas for MCO Incentives | ||

| Performance Area | # of States | States(39 of 40 MCO States Responding)* |

| Chronic Disease Management | 31 | AZ, CA, CO, DC, DE, FL, GA, HI, IA, IL, IN, KS, LA, MA, MI, MN, MO, MS, NE, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, SC, TX, WA, WI |

| Perinatal/Birth Outcome | 26 | CA, CO, DC, DE, FL, HI, IL, IN, KS, LA, MI, MO, MS, NE, NH, NJ, NM, NV, OH, OR, PA, RI, SC, TX, VA, WI |

| Mental Health | 24 | CA, CO, FL, GA, HI, IA, IL, IN, KS, LA, MA, MN, MO, NH, NM, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, SC, TX, WA, WI |

| Potentially Preventable Events | 22 | AZ, CA, DC, DE, FL, GA, IA, LA, MA, MI, MN, MO, NE, NH, NJ, OH, PA, RI, SC, TX, VA, WI |

| Substance Use Disorder | 19 | CO, FL, HI, IL, IN, KS, LA, MA, NH, NM, OH, OR, PA, RI, SC, TX, VA, WA, WI |

| Value-Based Purchasing | 17 | AZ, CA, DE, GA, KS, LA, MI, MN, NH, NM, OH, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, WA |

| Dental | 13 | AZ, CA, GA, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, NY, OR, PA, TX, WI |

| Member Satisfaction | 12 | DC, GA, HI, LA, MA, MI, NH, NY, OH, OR, SC, TX |

| Health Info Exchange | 4 | CA, MI, OH, WI |

| Health Disparities | 2 | CA, MI |

| Telehealth | 1 | NY |

| Other | 12 | CA, DE, HI, IA, IL, IN, MA, MI, NE, NV, TN, WI |

| *MD did not report. | ||

State-Mandated Performance Improvement Projects (PIPs)

For contracts starting on or after July 1, 2017, federal regulations mandate that states require each MCO or PHP to establish and implement an ongoing comprehensive quality assessment and performance improvement (QAPI) program for Medicaid services that includes Performance Improvement Projects (PIPs). PIPs may be designated by CMS, by states, or developed by health plans, but must be designed to achieve significant, sustainable improvement in health outcomes and enrollee satisfaction. In this year’s survey, states were asked to indicate whether they mandate MCO PIPs in a particular focus area. Thirty MCO states reported mandating certain PIPs in their MCO and PHP contracts in FY 2019 and four additional states indicated they were adding PIP requirements in FY 2020. The mandated PIP focus areas reported covered a wide range of programmatic topics, including child and adolescent wellness, perinatal/birth outcomes, behavioral health, dental health, chronic disease management, and long-term care, among other areas. Unlike the performance-based incentive initiatives mentioned above, a mandated PIP may not be directly tied to incentives or penalties, but nevertheless represents a performance area of particular importance to the state. Priority areas frequently reported include:

- Maternal and Child Health. Michigan reports requiring an MCO PIP to address racial disparities in the timeliness of prenatal care. Florida’s new MCO contracts require PIPs in the areas of reducing adverse birth outcomes, as well as reducing potentially preventable hospital events, transportation, and mental health or integrating mental health and primary care. In addition to a PIP related to consumer satisfaction, Iowa mandates an MCO PIP related to well child visits for children between 3 and 6 years of age.

- Chronic Care Disease Management. In addition to a PIP related to maternal health, DC also mandates a PIP related to comprehensive diabetes care. With a focus on efforts to reduce health disparities, Ohio reports requiring a PIP related to hypertension control in addition to a PIP on reducing preterm birth/infant mortality.

- Behavioral Health. Massachusetts mandates PIPs that correspond with two quality domains: Behavioral Health – prevention, assessment, and treatment of mental illness, including substance use and other dependencies; and Community Needs Assessment/ Risk Stratification – identifying and assessing priority populations for health conditions and social determinants of health and developing appropriate and timely interventions. In addition to a clinical PIP in the area of either child or perinatal health, Tennessee requires MCOs to implement a behavioral health PIP related to bipolar disorder, major depression, and schizophrenia.

- Long-Term Services and Supports. Pennsylvania MLTSS PIPs include a focus on transitioning beneficiaries from nursing facilities to home and community-based settings and strengthening care coordination. New Jersey MLTSS PIPs include initiatives to reduce falls and address gaps in care. Delaware mandates a PIP related to oral health of LTSS beneficiaries and at least one other MCO-defined PIP related to this population among five required PIPs in its MCO contracts.

MCO Contract Requirements

Alternative [Provider] Payment Models Within MCO Contracts

Value-based purchasing (VBP) strategies are important tools for states pursuing improved quality and outcomes and reduced costs of care within Medicaid and across payers. Generally speaking, VBP strategies include activities that hold a provider or MCO accountable for cost and quality of care.40 This often includes efforts to implement alternative payment models (APMs) which replace FFS/volume-driven provider payments with payment models that incentivize quality, coordination, and value (e.g., shared savings/shared risk arrangements and episode-based payments). Many states included a focus on adopting and promoting APMs as part of their federally-supported State Innovation Model (SIM) projects and as part of delivery system reform efforts approved under Section 1115 Medicaid waivers.41 A number of states are now encouraging or requiring MCOs to adopt APMs to advance VBP in Medicaid; our survey asked about requirements in MCO contracts.

More than half of MCO states (21 states) identified a specific target in their MCO contracts for the percentage of provider payments or plan members that MCOs must cover via APMs in FY 2019 (Exhibit 9). Three additional states plan to add a target percentage in FY 2020. States with targets linked to expenditures reported a wide range of currently required APM percentage targets ranging from a high of 80% (Hawaii) and 75% (Washington) to a low of 10% (Missouri and Wisconsin). Eleven states (Arizona, California, Louisiana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, and Washington) reported that their APM targets were linked to the Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network’s (LAN’s) APM Framework that categorizes APMs in tiers.42

In addition, fourteen states reported that their MCO contracts included incentives or penalties for meeting or failing to meet APM targets in FY 2019 (Exhibit 9). Three states reported plans to add penalties or incentives in FY 2020 (DC, New Hampshire, and Oregon).

| Exhibit 9: States that Require MCOs to Meet a Target % for Provider APMs | ||

| # of States | States | |

| In Place FY 2019 | 21 | AZ*, CA, DE*, HI, IA*, LA*, MA, MO*, NE, NH, NM*, NY*, OH*, PA*, RI*, SC*, TN*, TX*, WA*, WI, WV |

| Plan to Begin in FY 2020 | 3 | DC, NC, OR |

| States with an * reported MCO contracts include incentives or penalties for meeting or failing to meet APM targets in FY 2019. While MI did not report an APM target, it did report that a performance incentive related to APM requirements was in place in FY 2019. | ||

In FY 2019, eight states had contracts that required MCOs to participate in a state-directed VBP initiative (e.g., state—administered or directed episode of care or ACO initiative) and seven states planned to do so in FY 2020 (Exhibit 10). For example: California requires MCOs to make payments to Designated Public Hospitals on performance measures in four strategic categories; Illinois plans to require MCOs to participate in its new Integrated Health Home initiative; Ohio requires MCOs to participate in its SIM payment innovation efforts, episode-based payment model, and Comprehensive Primary Care program; Tennessee mandates that MCOs participate in the state’s episodes of care, patient-centered medical home and behavioral health home initiatives; and Virginia is planning to implement bundled payments for maternity and asthma that MCOs will be required to implement.

Further, 12 states in FY 2019 required MCOs to develop a VBP strategy within state-specified guidelines and five states planned to do so in FY 2020 (Exhibit 10). For example: Arizona requires its MCOs to develop strategies within the LAN-APM categories 2B and above; Kansas requires MCOs to implement VBP models that expand service coordination, increase employment, and provide better outcomes for foster children; Oregon requires its MCOs to develop new or expanded VBP efforts in specified care delivery focus areas; and Utah will require MCOs to adopt a VBP strategy to address hypertension.

| Exhibit 10: State Requirements for MCO VBP Initiatives | |||||

| Require MCOs to: | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | |||

| Participate in a state-directed VBP initiative | 8 States | CA, FL, GA, IA, MN, OH, RI, TN | 7 States | IL, KS, LA, MO, MS, PA, VA | |

| Develop a VBP strategy within state-specified guidelines | 12 States | AZ, DE, GA, HI, IA, KS, LA, MI, MN, NM, NY, RI, | 5 States | MO, NH, OR, PA, UT | |

Administrative Policies

Minimum Medical Loss Ratios

The Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) reflects the proportion of total capitation payments received by an MCO spent on clinical services and quality improvement. CMS published a final rule in 2016 that requires states to develop capitation rates for Medicaid to achieve an MLR of at least 85% in the rate year, for rating periods and contracts starting on or after July 1, 2019. Also, contracts taking effect on or after July 1, 2017 must include a requirement for plans to calculate and report an MLR.43 The 85% minimum MLR is the same standard that applies to Medicare Advantage and private large group plans. There is no federal requirement for Medicaid plans to pay remittances to the state if they fail to meet the MLR standard, but states have discretion to require remittances.

States were asked whether they require MCOs that do not meet the minimum MLR requirement to pay remittances. Twenty-four states reported that they always require MCOs to pay remittances, while six states indicated they sometimes require MCOs to pay remittances (Exhibit 11). States reporting that they sometimes require remittances often limit this requirement to certain MCO contracts – for example, MCO contracts for the adult expansion population. One state (South Carolina) reported allowing an exception to the remittance requirement if an MCO achieved a high National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) health insurance plan rating.44

| Exhibit 11: Medicaid MCO Minimum Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) Remittance Requirements as of July 1, 2019 | ||

| # of States | States | |

| State always requiring remittance | 24 | CO, DE, IA, IL, IN, KY, LA, MD, MI, MN, MO, MS, NE, NH, NJ, NM, NV, OR, PA, RI, UT, VA, WA, WV |

| State sometimes requiring remittance | 6 | AR, CA, MA, NY, OH, SC |

PCCM and PHP Program Changes

Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) Program Changes

Of the 12 states with PCCM programs, three reported enacting policies to increase PCCM enrollment in FY 2019 or FY 2020. Colorado reported growth in its PCCM-based Accountable Care Collaboratives in FY 2019 when it implemented a mandatory enrollment policy and Idaho reported that implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion in January 2020 would increase PCCM enrollment. Also, Alabama reported implementing two new PCCM programs that rely on contracts with PCCM entities:

- In FY 2019, Alabama implemented the “Integrated Care Network” (ICN) program that provides enhanced case management, education, and outreach services to most LTSS recipients in both HCBS and institutional settings.

- In FY 2020, Alabama reported plans to replace its current PCCM program (Patient 1st) and Maternity PHP program with a new PCCM entity program (the Alabama Coordinated Health Network) that will cover care coordination services.

Three states (California, North Carolina, and Vermont) reported actions to decrease enrollment in a PCCM program in FY 2019 or FY 2020. California and Vermont ended their PCCM programs in FY 2019 and North Carolina will be transitioning many PCCM enrollees to its new MCO program in FY 2020.

Limited-Benefit Prepaid Health Plans (PHP) Changes