Key Issues Related to COBRA Subsidies

Issue Brief

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended the economy, causing massive job loss and disrupting health coverage for millions of people. KFF estimates that of 78 million people in families experiencing a job loss as of May 2, 26.8 million could have lost job-based coverage and could become uninsured.

Coverage loss during a pandemic is particularly concerning. In a previous analysis, we estimated that treatment costs for people who are hospitalized for COVID-19 could average $20,000, rising to more than $80,000 in more complex cases. Congress has not required access to free treatment of COVID-19 for the uninsured; however, the CARES Act established a Provider Relief Fund, an unspecified portion of which will be used to reimburse providers treating uninsured patients with COVID-19. Substantial loss of employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) also puts millions at risk of being unable to afford other health care. In late 2018, a KFF/LA Times survey found that 54% of adults with ESI reported someone in the household having at least one chronic condition, such as heart disease, serious mental illness, diabetes, or cancer.

Most of the 26.8 million who are at risk of losing their job-based coverage are eligible to remain in that coverage under a federal law, the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA). COBRA requires that when individuals stand to lose job-based coverage due to a qualifying event – such as a layoff – they can continue enrollment in their existing group plan, usually at full cost to the enrollee.

Background on COBRA

COBRA applies to firms with 20 or more workers. When the qualifying event is termination of employment, individuals are generally eligible for up to 18 months of COBRA continuation coverage. (Other qualifying events, such as death of the covered employee or loss of dependent status, make people eligible for up to 36 months of COBRA continuation coverage.) Usually, individuals have 60 days to elect COBRA continuation, and another 45 days to pay the first premium, dating back to their qualifying event. However, a recent emergency regulation issued by the Trump Administration extends the amount of time people have to elect COBRA and pay premiums by 60 days after the national emergency period ends. For example, assuming the emergency period ends this summer on July 25, someone who received a COBRA notice on April 1 would have until late November to elect continuation coverage. The emergency regulation also extends the amount of time employers have to notify individuals of their right to elect COBRA continuation (usually 30 days) by the same amount of time.

For most people, particularly following job loss, the cost of COBRA continuation coverage is prohibitively expensive. Individuals must pay the total cost of the group health coverage (employee and employer share) plus a 2 percent administrative fee. On average, the total annual cost of employer-sponsored health coverage offered by firms of 20 or more in 2019 was $7,012 for single coverage and $20,599 for family coverage.

Looking at the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, only about 130,000 unemployed nonelderly adults had health coverage through COBRA in 2017, a year when more than 11.5 million nonelderly adults were unemployed. The uninsured rate among the unemployed was close to 30% that year. This suggests that unsubsidized COBRA does little to prevent coverage loss among people who lose their jobs.

The high cost of COBRA also invites adverse selection – that is, the people with highest health costs and risks are most likely to elect it. Our analysis finds average annualized health spending for COBRA enrollees (out-of-pocket and plan spending together) in 2018 was nearly twice that for other large group plan enrollees ($11,695 vs $6,144).

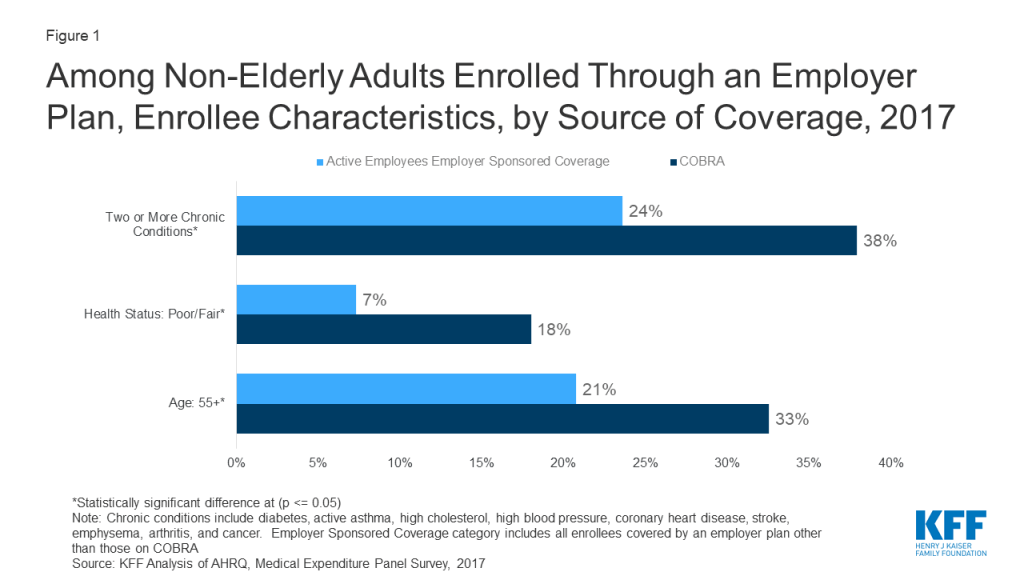

COBRA enrollees tend to be older than people enrolled in current job-based plans; on average 33% of COBRA enrollees are 55 or older, compared to 21% of active employees. In addition, COBRA enrollees are more likely to have multiple chronic conditions (38% vs 24%), and more than twice as likely to report poor health status (18% vs 7%) (Figure 1).

COBRA subsidies: past and current proposals

At several times in the past, Congress provided for partial subsidy of COBRA premiums for displaced workers. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) provided COBRA premium subsidies of 65% to help unemployed workers afford to continue enrollment in health coverage offered by their former employer. The ARRA COBRA subsidy was available to eligible individuals for up to 9 months initially; the eligibility period was later increased to up to 15 months. Eligible individuals were required to pay no more than 35% of COBRA premiums. Their former employers paid the other 65%, which was reimbursed through a credit against their payroll tax liability. Eligibility for the COBRA subsidy was phased out for higher income individuals with adjusted gross income between $125,000 and $145,000 ($250,000 to $290,000 for joint returns). The final evaluation of the ARRA COBRA subsidy program found that 34% of eligible individuals opted for subsidized COBRA coverage. Participation rates were highest among individuals with higher incomes and higher education. Among eligible individuals who did not elect COBRA, 80% said cost was the most important factor in their decision, even with the substantial subsidy.

In addition, ARRA amended an earlier COBRA subsidy program enacted in 2002 – the Health Coverage Tax Credit (HCTC) – specifically for workers laid off due to international trade-related factors, and who received Trade Adjustment Assistance benefits and met other qualifications. When enacted, the HCTC subsidized 65% of premiums for COBRA and certain other qualified health coverage options; ARRA increased the HCTC subsidy to 80%. A U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) review found that the partial subsidy and complex eligibility rules depressed take up of the HCTC. About 5% of potentially eligible individuals received the tax credit. After ARRA increased the HCTC subsidy, GAO found about 5.5% of potentially eligible individuals took the credit.

Recently, a fourth coronavirus relief measure, the Heroes Act, was passed in the House of Representative. It includes a provision to subsidize 100% of COBRA premiums for workers who would otherwise lose job-based coverage due to loss of employment or reduction in hours worked. People experiencing other COBRA qualifying events – such as death of the covered worker – would not be eligible for the subsidy. In addition, for furloughed workers whose health benefits continue while pay is suspended, the subsidy would also cover 100% of the employee’s portion of health premiums (employers would continue to pay their portion). Employers would cover the entire cost of health coverage for eligible individuals, then be reimbursed through a credit against their payroll tax liability or via a refund. The subsidy could be claimed for COBRA coverage months between March 1, 2020 and January 31, 2021. People would lose eligibility for the subsidy when they become eligible for other employer-sponsored health coverage or Medicare.

Other options and tradeoffs for people losing job-based coverage

The KFF analysis estimates that about 79% of people who have lost job-based coverage and could become uninsured are eligible for either Medicaid/CHIP (12.7 million, or 47%) or for subsidized marketplace plans (8.4 million, or 31%). Approximately 5.7 million will not be eligible for subsidized coverage for a variety of reasons.

Eligibility for coverage doesn’t always translate to enrollment. In 2018, there were more uninsured individuals eligible for subsidized marketplace plans that were enrolled in such plans — 9.2 million uninsured vs. 8.6 million enrolled. In addition that year 6.7 million uninsured adults and children were eligible for Medicaid or other public coverage.

In evaluating health coverage options, people would consider differences in premiums, cost sharing, and provider networks, among other factors. In addition, awareness of coverage options in the first place, as well as complexity of the application process affects enrollment outcomes. Subsidized COBRA would add a new coverage option, potentially changing the tradeoffs people face and their ability to remain insured.

Premiums and Cost Sharing

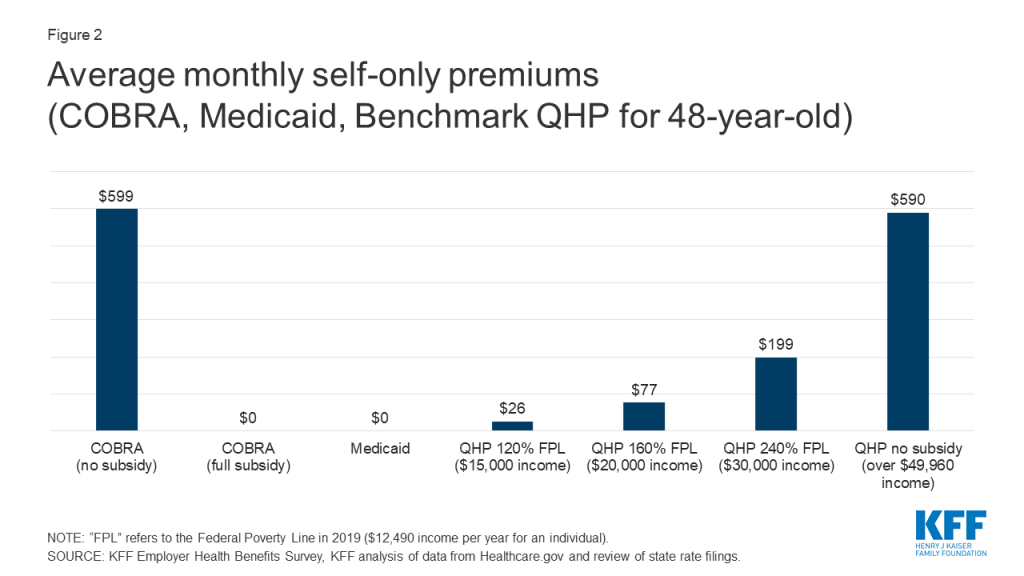

For the newly unemployed, unsubsidized COBRA generally will be the most expensive coverage option. Medicaid coverage in most states requires no premium. Marketplace plans are subsidized on a sliding scale for eligible individuals with income between 100% and 400% FPL; at every income level people must contribute at least a portion of the monthly premium for the benchmark plan, and the required premium contribution approaches 10 percent of gross income at 300% FPL. If fully subsidized, the premium cost of COBRA for individuals would be comparable to Medicaid, and would be less (far less, depending on income) than premium contribution required to purchase the average benchmark silver plan on the ACA Marketplace. (Figure 2)

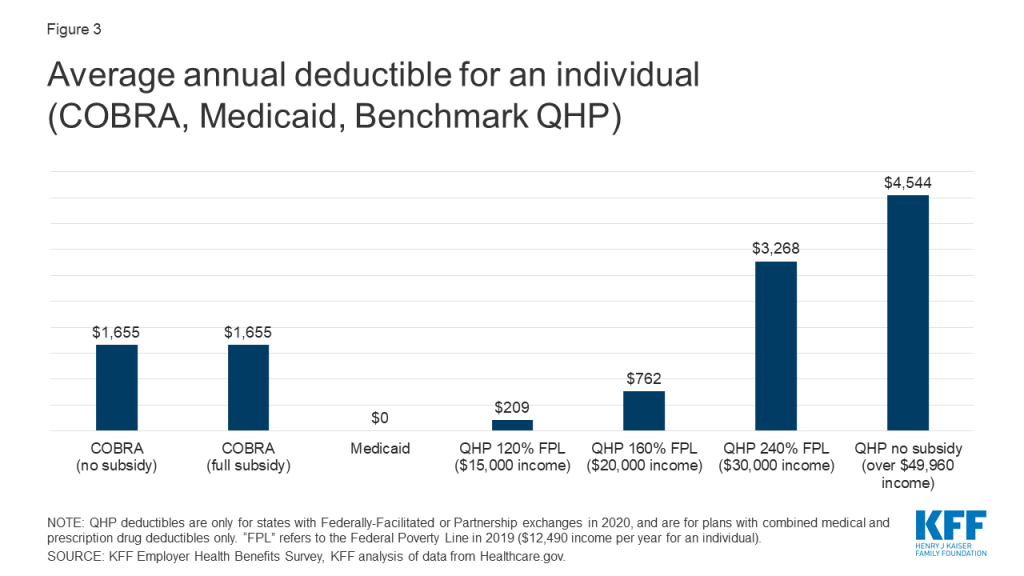

Under employer-based plans annual deductibles tend to be high. The average actuarial value of employment based plans in 2017 was about 85%, somewhat more generous than a gold-level marketplace plan. The average annual deductible for self-only coverage under job-based plans was $1,655 in 2019. Most employer plans do not vary deductibles based on income.

Under Marketplace plans, cost sharing is much higher. Benchmark silver plans have an actuarial value of roughly 70%, with deductibles averaging $4,544. However, cost sharing subsidies are available to lower-income enrollees on a sliding scale, and most marketplace enrollees receive them. For people with incomes of 100%-150% FPL, the silver plan AV is increased to 94% and the average annual deductible is reduced to $209. Between 150% and 200% FPL, the silver plan AV is increased to 87% and the average annual deductible is $762. Cost sharing subsidies are more modest between 200% and 250% FPL; the silver plan AV increases slightly to 74% and the average deductible is $3,268.

Medicaid generally does not impose deductibles; in 22 states, adults face limited copays for certain services (e.g., 13 states require copays that generally are up to $4 for physician visits, while 18 states require copays ranging from $0.50 to $4 for generic prescription drugs.) (Figure 2)

Proposed COBRA subsidies would not affect the level of cost sharing under continuation coverage. As a result, low income individuals (less than 200% FPL) could find cost sharing reduced if they transition to Medicaid or CSR marketplace plans; otherwise people would tend to face higher cost sharing under marketplace plans compared to COBRA continuation (Figure 3).

Provider networks

Large employer health plans tend to offer broad choice of providers in their networks. In 2019, 79% of large firms characterized their largest plan option as having a “very broad” provider network, although six percent of large firms offered at least one narrow network plan option Only 2% of offering firms say they eliminated a hospital or health system from a provider network in the prior year to reduce plan costs. By contrast, marketplace plans rely heavily on narrow provider networks to control costs, and are dominated by plans with restrictive provider networks. This year 78% of qualified health plans (QHP) offered in healthcare.gov states are closed network plans (HMOs or EPOs), compared to 60% in 2016.

Though research indicates that, overall, most primary care providers and specialists accept Medicaid, provider participation in Medicaid is a subject of much debate. Providers are less likely to accept new Medicaid patients than new patients insured by other payers, and lower participation rates among some types of specialists remain an area of concern. However, gaps in access to certain providers including psychiatrists, some specialists, and dentists, are ongoing challenges in Medicaid and often in the health system more broadly due to overall provider shortages, and geographic maldistribution of health care providers. In most states, Medicaid coverage is provided through private managed care organizations (MCOs), and MCOs are responsible under their contracts with states for ensuring adequate provider networks.

Added enrollment barriers

In most states, people losing job-based coverage who are eligible to enroll in marketplace plans must do so within a limited period of time. Loss of other coverage is a qualifying event that triggers a 60-day special enrollment period (SEP), when people can sign up for marketplace coverage outside of the annual open enrollment period. (The recent emergency regulation extending the time people have to elect COBRA does not extend the duration of marketplace SEPs.) Complicating this process, new rules adopted in 2017 require applicants to document eligibility for the SEP before they can enroll in marketplace coverage. That appears to have made it harder for people to use the SEP. The federal marketplace resolved some 800,000 SEP verifications over 2018 and 2019. By contrast, prior to adoption of the more stringent verification requirements, there were nearly 950,000 SEP enrollments during the first half of 2015 alone.

The ACA establishing streamlined and modernized eligibility and enrollment systems for Medicaid across all states. To support states as enrollment in Medicaid grows and ensure enrollees maintain coverage, federal legislation provides states a temporary 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal matching rate and establishes conditions states must meet to access the enhanced funding. However, states may face capacity issues as demand for Medicaid grows. A number of states are taking actions to further streamline and simplify eligibility and processes and ease administrative burdens. However, many people who may be newly eligible for Medicaid may not know they can qualify and may not understand that they can apply anytime, without waiting for an open enrollment period.

In addition, new rules about what income to count toward eligibility for subsidized health care are complex and may be confusing for some consumers. In the CARES Act, Congress temporarily supplemented state unemployment insurance (UI) benefits, adding another $600 per week in federal benefits through the end of July, and specifying this supplement should be disregarded in determining eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP, but counted in determining eligibility for marketplace subsidies. To the extent consumers may not understand how to accurately report income under these rules, their ability to successfully apply for Medicaid, CHIP, or marketplace subsidies could be affected.

Recent federal cuts in outreach and enrollment assistance also could make it harder for people unfamiliar with either the marketplace or Medicaid to identify and understand these coverage options and successfully enroll.

In contrast, COBRA continuation coverage, by definition, does not require a transition to new coverage. People satisfied with their current coverage may be more likely to remain enrolled, if they can afford to. Overall, people with employer-sponsored health coverage view their health plan favorably, suggesting that, all other things equal, many might prefer to keep their current coverage. A late 2018 KFF/LA Times survey of adults with ESI found that overall, roughly seven in ten people with ESI give it a grade of either “A” or “B,” and about six in ten say they think their employer is offering them the best possible deal for coverage. However, satisfaction with job-based plans was lower for people in plans with higher deductibles.

Discussion

The availability of COBRA subsidies could help prevent health coverage loss for up to tens of millions of displaced workers. As proposed, COBRA subsidies would give workers the option to remain affordably in their current job-based plan. Subsidies could also reduce adverse selection against employer plans experienced today by unsubsidized COBRA enrollees.

Under current law, most displaced workers will also be eligible for other, subsidized, coverage options – marketplace plans and Medicaid/CHIP. Some might choose these current new coverage sources instead of subsidized COBRA. Premiums paid by individuals for fully subsidized COBRA would be comparable to Medicaid – that is, zero premiums. Marketplace plan premiums would generally be higher than subsidized COBRA, and much higher for individuals whose incomes make them ineligible for marketplace premium tax credits. On average, cost sharing under COBRA would be higher than under Medicaid, particularly if displaced workers had not yet satisfied their annual deductible. Cost sharing under marketplace plans could be much lower for individuals eligible for CSR; but could be much higher for people with income more than twice the poverty level. Finally, individuals losing their jobs and job-based coverage might not be aware of other Medicaid and marketplace coverage options, or successfully navigate the application and transition to other coverage. For them, COBRA continuation coverage could be more familiar and less administratively complex.

Beyond tradeoffs for individuals, COBRA subsidies raise other questions of cost-efficiency. Historical national data shows that employer plans generally are not as successful as public plans at controlling the rate of growth in health expenditures. On average, private health plans pay prices for hospital and medical services that are nearly twice that paid by Medicare. In addition, COBRA premium subsidies could generate a windfall for insurers and health plans whose 2020 premiums were established prior to the pandemic, At least in the short term, as patients delay elective procedures, major insurers have reported rising profits, some of which may need to be returned in rebates next year.

At $106 billion over two years, the federal cost of a 100% COBRA subsidy would be substantial, both because of the per person cost and because it is likely that most, even nearly all, of those eligible would take advantage of this option to maintain free health coverage.

Methods

This brief analyzes data from the 2017 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), a cross-sectional survey consisting of two-year longitudinal panels. The 2017 MEPS data set reflects data collected during both panel 21 (rounds 3, 4, and 5) and panel 22 (rounds 1, 2, and 3). The survey uses computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) software to interview 19,351 households gathering information on 31,880 people. For this analysis, we looked a subset of people ages 18 to 64. Statistics are weighted using the MEPS person weight. Individual enrollment in COBRA was determined using the MEPS Person Round Plan file. We calculated a point-in-time cobra enrollment at panel 21 round 3 and panel 22 round 1. The MEPS Person Round Plan file was merged on to the MEPS Full Year consolidated file, which contained enrollment data by source of coverage. Each source of insurance was subset to the months January, February, March, and April to coincide with the point when the COBRA question was collected. The different sources of insurance are not mutually exclusive, so a hierarchy was created as follows: COBRA, Medicaid, Medicare, ESI, Non Group, Uninsured. The Unemployment rate was calculated by using the following categories: people who could not find work, people who were unable to work because of a disability, people unemployed because of temporarily layoff, and people who were waiting to start a new job.

Data on premiums and deductibles for 2020 QHP Marketplace plans come from Healthcare.gov and KFF review of state rate filings. Average QHP premiums were calculated as the average of premiums for the second-lowest cost silver plan (the benchmark plan) in each county in 2020 for a 48-year-old non-smoking individual, and are weighted by 2019 enrollment. Average QHP plan deductibles only include plans offered in federally-facilitated and partnership exchanges. Because many Marketplace plans are offered in multiple rating areas within a state, to calculate average deductibles we reduced the number of plans so that each benefit package was counted only once for each state. Average deductibles are simple averages of the plans that are available and are not weighted by enrollment.

Unsubsidized premiums and deductibles for those with employer coverage are calculated as the average premiums (including both the employer and worker contributions) and average single-coverage deductible. Premium costs do not include a two percent administrative fee that enrollees may face. KFF conducted the annual Employer Health Benefits Survey between January and July of 2019. It included 2,012 randomly-selected, non-federal public and private firms with three or more employees, for more information see here.