Maternal Health in the Build Back Better Act

Maternal health is receiving new attention by policymakers in the U.S. who are trying to address pregnancy-related deaths, particularly the substantially higher rates among Black and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) people compared to other racial and ethnic groups.

The Build Back Better Act (BBBA) includes several provisions aimed at improving maternal health, particularly for people of color. The debate over the BBBA comes at the same time that numerous other efforts to improve maternal health are under way, by the federal government as well as non-governmental organizations.

Medicaid Postpartum Coverage Extension

Increasing attention has centered on postpartum care, including recovery from childbirth, follow up on health complications, management of chronic conditions, access to family planning, and mental health care. However, for many birthing parents who live in states that have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA, coverage for this care is elusive and access to services is poor. The Medicaid program covers more than 40% of births nationally, including two-thirds among Black and AIAN people.

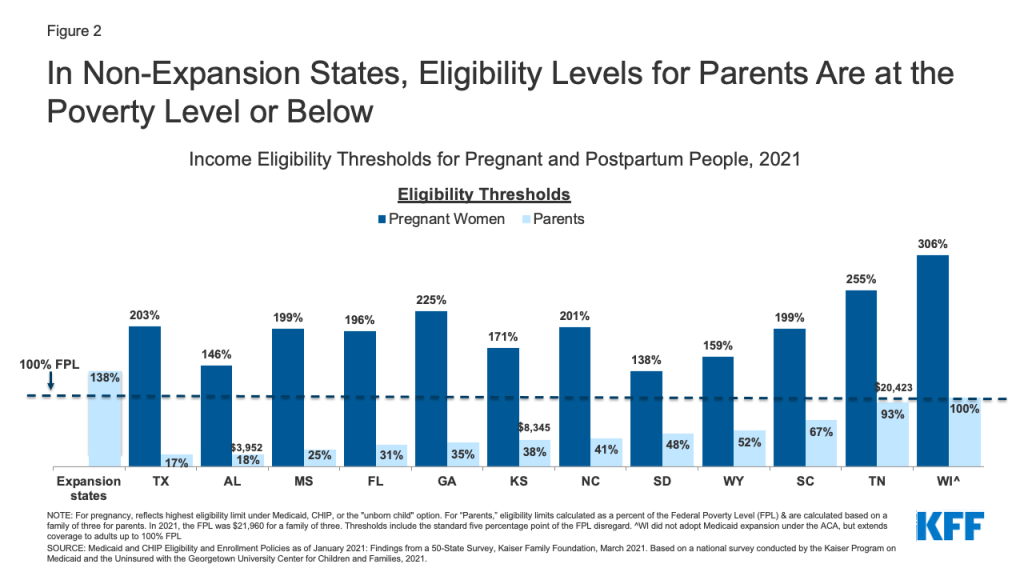

Federal law requires states to extend Medicaid eligibility to pregnant individuals with household incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) through 60 days postpartum. In non-expansion states, after the postpartum period, birthing parents lose pregnancy eligibility and must re-qualify as “parents of dependent children” to remain on Medicaid. However, many do not qualify and become uninsured because Medicaid income eligibility levels for parents are much lower than for pregnant people. Additionally, for many, their incomes are too low to qualify for subsidized private plans through the ACA Marketplace, which are only available to those with incomes above the poverty level. There were about 632,000 Medicaid births in non-expansion states in 2019 (Figure 1).

For example, in Alabama (Figure 2), a married mother with a newborn is in this coverage gap if she and her partner have an annual income above $3,952 (18% FPL). In contrast, their counterparts in expansion states can remain on Medicaid if their income is up to 138% FPL or qualify for Marketplace subsidies if it is higher. (Note: Currently postpartum people covered by Medicaid can remain on the program beyond 60 days because of a continuous enrollment requirement enacted in 2020 that lasts through the COVID public health emergency.)

The 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) gave states the option to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months for up to five years, which some states plan to adopt. The BBBA builds upon this by requiring all states to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months permanently. Postpartum coverage transitions happen in all states, but more parents become uninsured in non-expansion states. The federal government estimates that mandatory postpartum extension would result in about 720,000 additional people remaining eligible through 12 months postpartum, with the number of continuously eligible increasing by 65 percentage points in non-expansion states and 38 percentage points in expansion states. The estimated cost of this provision is $1.2 billion over 10 years.

In addition to extending the postpartum period, the BBBA seeks to close the coverage gap temporarily by allowing people with incomes below 100% FPL who reside in non-expansion states and are ineligible for Medicaid to qualify for subsidies on the ACA Marketplace until 2025. This would provide a pathway to coverage for people before pregnancy, for all parents, and for those without children, at an estimated federal cost of $57 billion over 10 years.

Maternal Health Homes

The idea behind the maternal health home model is to provide financial incentives for providers to better coordinate and improve quality of care through the perinatal period. Some states have piloted maternal health homes and seen positive impacts on health outcomes. A provision of the BBBA would give states an increase in the federal match (FMAP) of 15 percentage points for two years if they deliver care through maternal health homes. The estimated federal cost is $1.0 billion over 10 years.

Improving Care and Addressing Inequities

The BBBA also seeks to strengthen care by authorizing approximately $1 billion in grants that would incorporate many elements of the MOMNIBUS, a legislative package that focuses on improving maternal and infant health for people of color. Funds would:

- Social Determinants of Health—Support community-based groups addressing issues that intersect with maternal health such as poverty, food, housing, and climate change.

- Workforce—Support universities, training programs, and other organizations to grow and diversify the perinatal workforce, including nurses, midwives, doulas, and substance use and mental health workers and to identify areas with shortages of maternity care workers.

- Delivery System—Enhance perinatal quality collaboratives that provide quality improvement tools for maternity providers; expand and incorporate use of technology and digital tools in maternity care; provide and strengthen anti-bias training to perinatal workers.

- Data and Research—Expand research and data collection on maternal health and inequities through academic institutions, federal surveys, state-level maternal mortality review committees, and the NIH.

Paid Leave

The BBBA also proposes to establish a national paid family and medical leave policy, which has been associated with mental and physical health and well-being for new parents and infants, workforce retention and gender equity. Paid leave provides an important foundation for postpartum health and child rearing and is available in every other industrialized nation. The BBBA proposes four weeks of paid family and medical leave annually to all workers for time off to welcome a child, recover from serious illness, or care for an ill family member, with an estimated federal cost over 10 years of approximately $205 billion. However, while paid leave was included in the bill passed by the House of Representatives, it may not pass in the Senate, as Senator Manchin of West Virginia has expressed opposition to this proposal.

Many states have already indicated an interest in expanding postpartum Medicaid coverage and addressing maternal health disparities. The BBBA could provide more supports to states and community organizations to invest further in improving maternal health.