Medicare Accelerated and Advance Payments for COVID-19 Revenue Loss: More Time to Repay

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, when it became clear that hospitals and other providers were losing revenue due to a sudden drop in admissions, procedures, and visits, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Congress took action to mitigate the financial impact on health care providers across the country. In March 2020, CMS accelerated Medicare payments to hospitals and advanced payments to physicians and other providers to minimize the effects of revenue shortfalls, and Congress passed the CARES Act, which provided grants to providers to help offset losses due to the pandemic. This brief provides an overview and status update of payments made to providers in response to the pandemic through Medicare’s accelerated and advance payments programs, as well other sources of funding.

What are the Accelerated and Advance Payment Programs and how were these payments allocated in response to COVID-19?

The Medicare Accelerated and Advance Payment Programs, which existed before the pandemic, are designed to help hospitals and other providers facing cash flow disruptions during an emergency. These are loans that must be paid back, with timelines and terms for repayment. The CARES Act significantly expanded this program to include a broader set of hospitals, health professionals, and suppliers during the COVID-19 public health emergency. These loans are paid out of the Medicare Hospital Insurance (Part A) and the Supplementary Medical Insurance (Part B) trust funds.

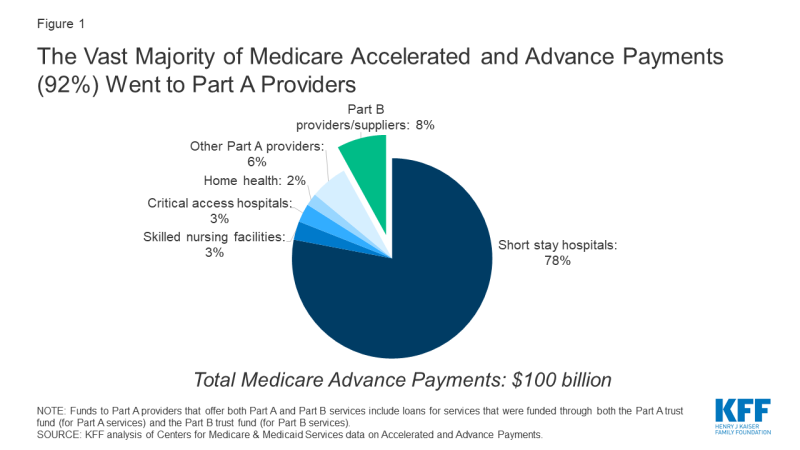

As of May 2020, a total of $100 billion had been distributed to hospitals and other types of providers impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic through the accelerated and advance payment programs. The vast majority of these payments ($92 billion) went to providers that participate in Part A, which pays for inpatient hospital stays, skilled nursing facility (SNF) stays, some home health visits, and hospice care. Of this amount, $78 billion went to short stay hospitals and a combined $5 billion went to skilled nursing facilities and home health providers (Figure 1). Advance payments to Part A providers that offer both Part A and Part B services include loans for services that were funded through both the Part A trust fund (for Part A services) and the Part B trust fund (for Part B services).

Figure 1: The Vast Majority of Medicare Accelerated and Advance Payments (92%) Went to Part A Providers

The loans made under this program are an advance on reimbursement from traditional (fee-for-service) Medicare – an approach that may be less helpful to hospitals and other providers that serve a relatively large share of patients enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans. The share of Medicare beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans varies widely by state and county, ranging from less than 1% in some counties to more than 60% in others, including two-thirds of beneficiaries in Miami-Dade county in Florida.

What other financial assistance have providers received during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Money that providers received through the Accelerated and Advance Payment programs in the spring of 2020 likely served as a lifeline for many providers that were facing dramatic drops in revenue due to delays in non-emergency procedures. But these loans are not the only assistance providers have received since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Other financial assistance includes:

- Provider relief grants: The CARES Act and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act allocated $175 billion for grants to health care providers that do not have to be paid back. Of the $144 billion that already has been allocated, $50 billion went to Medicare providers proportionately based on their total net patient revenue. This formula favored hospitals that get most of their revenue from private insurance, which typically reimburses at prices that are twice as high as what Medicare pays, disproportionately helping for-profit hospitals and hospitals with higher operating margins. Additionally, $22 billion in grants went to hospitals that treated a high number of COVID-19 inpatients, $11 billion went to rural providers, and $13 billion went to safety net hospitals.

- Treasury department and Small Business Administration loans: Health care providers are potentially eligible for some of the loan programs included in the CARES Act, including the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). Under the PPP for small businesses, loans are forgiven if employers do not lay off workers and meet other criteria. According to a Treasury Department analysis, health care providers received nearly $68 billion of the $520 billion in PPP loans that have been distributed. The CARES Act also appropriated $454 billion for loans to qualifying larger businesses – including hospitals and other large health care entities – but the eligibility criteria for those loans have limited their reach.

- Increase in Medicare COVID-19 inpatient reimbursement: During the public health emergency, Medicare is increasing all inpatient reimbursement for COVID-19 patients by 20%. This payment increase applies to all hospitals paid under the inpatient prospective payment system and so would not apply to critical access hospitals. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that this change will increase Medicare spending by about $3 billion.

What is the current status of the Accelerated and Advance Payment Programs?

Providers that received the advanced and accelerated payments were scheduled to begin repayment of those loans in August 2020, but CMS delayed the start of repayment at that time. In the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2021 and Other Extensions Act (H.R. 8337), signed into law on October 1, 2020, Congress gave hospitals and other providers that received Medicare accelerated and advance payments one year from when the first loan payment was made to begin making repayments – delaying the start of the repayment period to spring of 2021.

Once repayments begin, Medicare providers can continue to submit claims, but a portion of the new claims will be offset to repay the loans (25% during the first 11 months of repayment and 50% during the next six months). In other words, a portion of the Medicare reimbursements that providers would otherwise receive will instead go towards repaying the loans they received from Medicare. Providers are required to have paid back the loans in full 29 months after the first payment was made. If any money remains unpaid at that time, an interest rate of 4 percent will begin to be charged.

These modified repayment terms are more favorable than those that are typically attached to loans provided through the accelerated and advance payment programs. The original timeline for repaying the loans was shorter and the original terms required that loan repayment would fully offset Medicare reimbursements that providers would have otherwise received for claims submitted during the repayment period. Additionally, money that was unpaid after the final due date was originally subject to an interest rate of about 10 percent.

What is the implication for providers of repaying these amounts?

The Medicare advance and accelerated payment program provided quick access to funds at a time when many hospitals were facing an unexpected and unprecedented disruption in cash flow. While some hospitals are continuing to struggle due to expenses and lost revenue related to coronavirus, other hospitals have posted profits and are reporting no liquidity concerns. As of July 2020, hospital admissions had rebounded to 92% of pre-pandemic baseline volumes.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic, hospitals’ financial situations varied widely, with some hospitals having much larger financial reserves than others. In 2018, the median hospital had enough cash on hand to pay its operating expenses for 53 days, but the 25th percentile hospital only hand enough cash on hand for 8 days. Smaller hospitals and rural hospitals are among those most likely to face financial challenges in the wake of COVID-19 revenue loss and may be those that most needed the recent changes to the loan repayment terms.

What are the implications for Medicare of modifications to the repayment requirements?

Before Congress authorized an extended timeline for repaying these loans and other modifications to the terms of repayment, some providers had been lobbying to have the loans forgiven altogether for all hospitals or a subset of those that have been most adversely affected by the pandemic. It is possible that the push for loan forgiveness will resume in the spring of 2021, closer to the new date for the start of loan repayments.

Modifications to the repayment requirements that would cancel amounts owed to Medicare for some (if not all) providers would have negative repercussions on the Medicare Hospital Insurance (Part A) trust fund, which is already facing a loss of payroll tax revenue due to due to the unemployment crisis brought about by the pandemic. Without taking into account the expected effects of the pandemic, government actuaries estimated that trust fund reserves would be $185 billion at the end of 2020, which is likely to be an overestimate because it does not take into account the loss of revenue due to the pandemic. Outlays from the trust fund have also been affected by the 20% increase in Medicare inpatient reimbursement for COVID-19 patients authorized by the CARES Act, although there have also been offsets in spending due to reductions in the use of health care by Medicare beneficiaries unrelated to the coronavirus.

In 2020, the Medicare trustees projected that the Part A trust fund would be insolvent by 2026, but that projection did not account for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Medicare spending and revenues. A more recent estimate from the Congressional Budget Office projects that the Part A trust fund will be depleted in 2024. If a significant share of the advance payment loans was not repaid and no other changes were made to hold the Part A trust fund harmless, it could have a material impact on the solvency of the trust fund and its ability to fully meet obligations beyond the next few years.

In the 2021 continuing appropriations legislation, Congress authorized a transfer of money from the general fund of the Treasury to the Medicare Part B (Supplementary Medical Insurance, or SMI) trust fund to equal the amount paid to Part B providers through the Medicare Advance Payment program. This transfer will help to protect Medicare beneficiaries from a steep Part B premium increase that would have occurred otherwise in 2021 to account for higher Part B spending associated with the advance payments.

If policymakers consider additional adjustments to the terms for repayment of loans from hospitals and other health care providers, they may want to take into account the different sources of funds that have been distributed since the start of the pandemic, the fact that some providers have recovered more quickly than others, and the extent to which any change could exacerbate the fiscal strain on the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund.