Role of Mothers in Assuring Children Receive COVID-19 Vaccinations

Introduction

Much has been written about the multiple roles that women, particularly mothers have played in all stages of the pandemic – including as frontline workers, paid and informal caregivers, and ad hoc homeschool teachers just to name a few. Mothers will also play a pivotal role in the national efforts to get as many eligible children as possible vaccinated against COVID-19. Use of the COVID-19 vaccine from Pfizer has now been authorized for adolescents ages 12 – 15, and younger children may become eligible for vaccination later this year. While on average children have had less severe impact of COVID-19, cases of death, severe illness, and long-term consequences of COVID-19 have been documented among children. Even when they do not fall ill from COVID-19, asymptomatic children can be a source of spread of the disease.

Who will ensure that kids receive vaccinations?

Parents will be the ones who determine whether children get their vaccines (Figure 1). In the 2020 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey, roughly seven in ten mothers of children under 18 say they are usually the ones who select their children’s doctor (68%), take children to medical appointments (70%) and follow up on recommended care (67%). Mothers and fathers differ somewhat on their assessment of involvement in children’s health care, but even among fathers, less than a fifth report they take care of these tasks and a substantial share say their partner takes care of them (Figure 1). However, about half of fathers say they share these responsibilities equally with a partner or other parent, compared to about a quarter of mothers.

While the majority of mothers in all groups say they are the ones who usually take care of kids’ health care needs, it is higher among Black and low-income mothers compared to those who are White and low-income, as we have previously reported. These differences are particularly important, given the disproportionate toll of the pandemic on communities of color and those who are low-income. More than one-third (36%) of children ages 12-15 are in low-income families. Not surprisingly, single mothers shoulder a higher share of children’s health care needs compared to those who are married/living with a partner.

Another concern will be how mothers will find the time to take their children to get vaccinated and to deal with the potential side effects from the vaccine their children may experience and the impact on their pay. The Pfizer vaccine requires two shots and children may experience side effects that prevent them from attending school or other care. For employed parents, this may require taking time off from work and this responsibility has typically fallen on the shoulders of the mother. Six in ten (61%) employed mothers report that they are usually the ones who care for children when they are sick and cannot go to school, and nearly half (46%) of this group report that they are not paid for that time off. This gap is larger among some groups, particularly mothers who are Hispanic, low-income, or single, who also are more likely to have to care for children when they are sick and cannot attend school (Figure 2). In fact, less than half of employed low-income mothers (46%) report being offered paid sick leave compared to nearly three in four with higher incomes (72%).

What do we know about parents’ interest in vaccines?

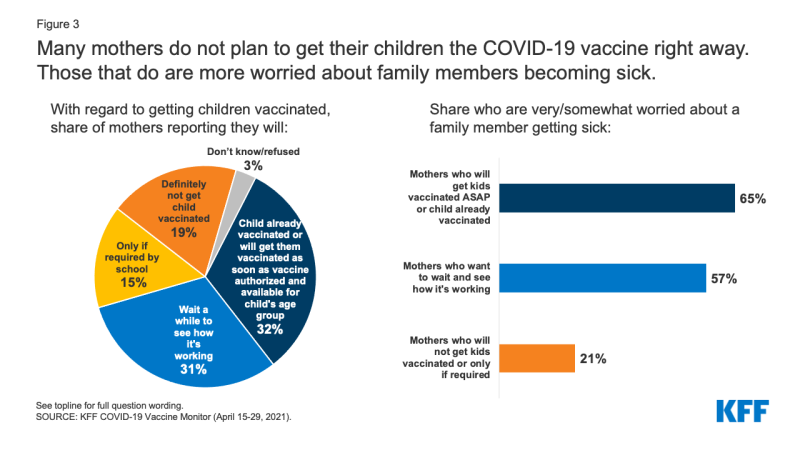

While mothers have traditionally played a leading role in managing their children’ health care, it is unclear how families are making decisions about whether their children should be vaccinated against COVID-19. Data from the latest KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor find that as of mid-April (before the FDA authorized the vaccines for use in children ages 12-15), about a third of mothers (32%) of children under 18 said they would get their children vaccinated as soon as a vaccine was authorized for their child’s age group or have already gotten their child vaccinated (Figure 3). Nearly a third (31%) wanted to wait and see how the vaccine is working, 15% said they would only get it if required for school, and about a fifth (19%) said they would not get their children vaccinated. Rates among fathers are similar.

While the majority of mothers said they were not planning to get their children vaccinated right away, nearly half (48%) of mothers and 40% of fathers say they are worried (very or somewhat) about someone in their family getting sick from COVID-19. The share who are worried about someone in their family getting sick from COVID-19 rises to 65% among mothers whose kids are already vaccinated or want to get their kids vaccinated right away, 57% among mothers who want to wait and see before deciding on children’s vaccinations, but only 21% among mothers who do not want to get their children vaccinated or will only do so if required.

Figure 3: Many mothers do not plan to get their children the COVID-19 vaccine right away. Those that do are more worried about family members becoming sick.

When it comes to adult vaccinations, more than half (56%) of mothers with children under 18 said they themselves have already been vaccinated or want to get vaccinated as soon as possible. A fifth of mothers said they want to wait and see about getting vaccinated themselves (20%) and about a fifth (21%) said they will not get vaccinated or will do it only if it is required (Figure 4). These percentages are similar among fathers.

While we do not know the rationale for the lack of urgency some parents have so far regarding getting their children vaccinated, it can be informative to look at the reasons that parents state for not getting vaccinated yet themselves (Table 1). Among unvaccinated parents, the vast majority of mothers (88%) are concerned about experiencing serious side effects, higher than fathers (74%). Relatedly, nearly two-thirds of mothers (65%) also report concern about missing work if the side effects make them feel sick for a day or more, compared to less than half of fathers (47%). Many mothers and fathers also fear that the vaccines are not as safe as they are said to be.

Additionally, a larger share of unvaccinated parents with household incomes below $40,000 annually compared to those with higher incomes are also worried about experiencing serious side effects and having to miss work due to vaccine side effects. Parents may have these same concerns about their children experiencing side effects and needing to miss work to attend to them, particularly if they do not have paid sick leave benefits. Compared to higher income parents, a larger share of lower-income parents are also concerned about having to pay out-of-pocket costs for the vaccines (48% vs. 24%) and not being able to get the vaccine from a place they trust (48% vs. 27%).

Now that the FDA has authorized the Pfizer vaccine for adolescents, with younger children likely soon to follow, eyes have begun to shift to vaccine uptake among children. However, with less than a third of parents ready to get their children vaccinated right away, it will be important to provide accurate information to address their concerns. In addition, many parents, particularly mothers, report apprehension about side effects, and missing work with respect to their own vaccination decisions. Efforts to address these concerns such as paid sick leave or time off for children’s vaccinations could provide indirect avenues to allay potential fears regarding vaccinations for their children as well. Mothers have long played an outsize role in managing their children’s health, a role which could be central in determining how many children get vaccinated for COVID-19.