Views and Experiences with End-of-Life Medical Care in Japan, Italy, the United States, and Brazil: A Cross-Country Survey

Country Highlights: Italy

Italians want their government to take responsibility for the aging population, but most doubt its preparedness to do so.

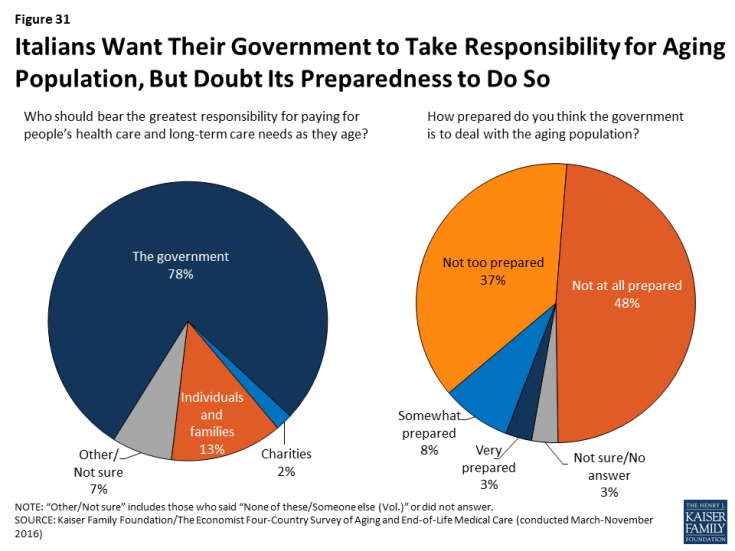

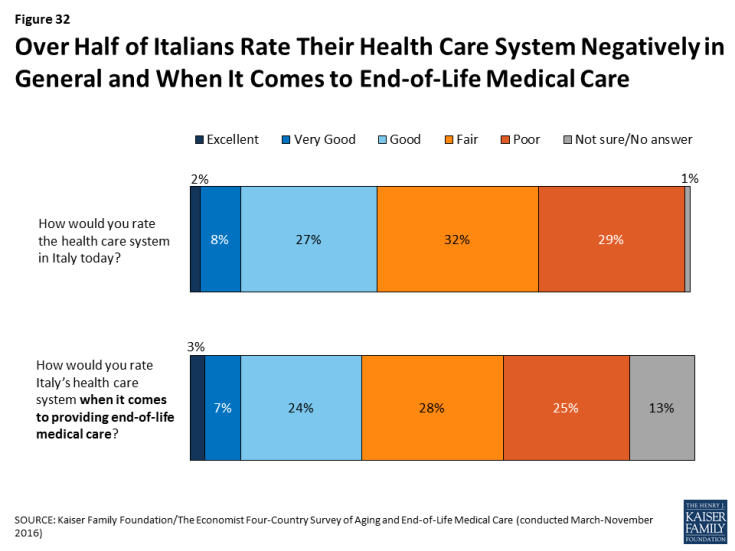

In Italy, the second-oldest country in our survey, 72 percent see the aging of the population as a problem – including 57 percent who say it’s a major problem – and roughly eight in ten (78 percent) say it should be the responsibility of the government to pay for people’s health and long-term care needs as they age. Yet nearly nine in ten Italians say the government is “not too prepared” (37 percent) or “not at all prepared” (48 percent) to deal with the aging population, and two-thirds (65 percent) say the same about the country’s health care system. Furthermore, six in ten (61 percent) give the country’s health care system a fair or poor rating overall, and half (53 percent) say the same when it comes to end-of-life medical care.

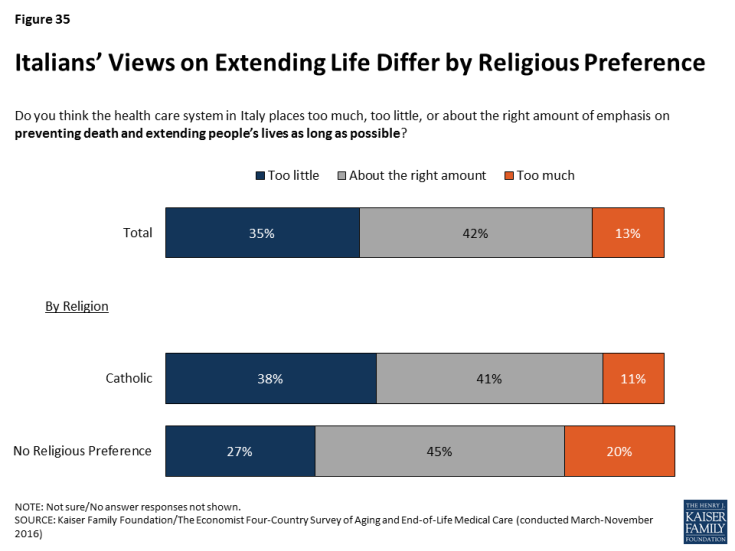

Figure 31: Italians Want Their Government to Take Responsibility for Aging Population, But Doubt Its Preparedness to Do So

Figure 32: Over Half of Italians Rate Their Health Care System Negatively in General and When It Comes to End-of-Life Medical Care

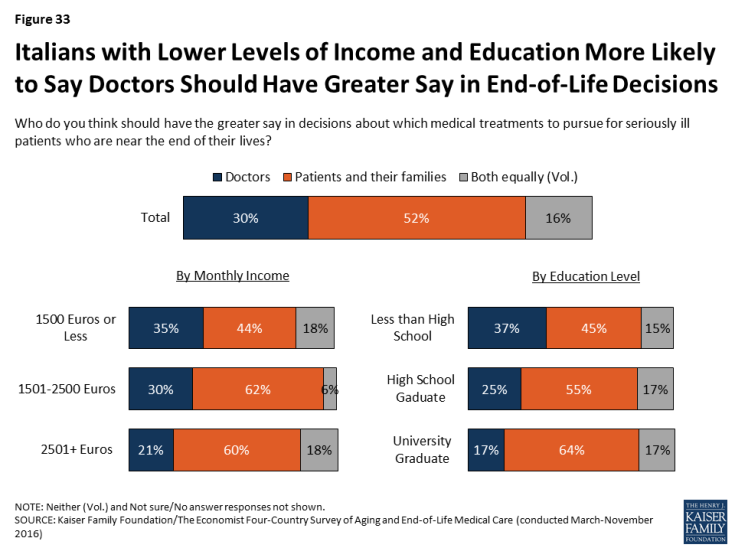

Italians are more likely than residents of some other countries surveyed to place decisions about end-of-life medical care in the hands of doctors. This is particularly true among Italians with lower incomes and lower levels of education.

While just 11 percent of Italians say they have had a serious conversation with a doctor about their own wishes for end-of-life medical care and just 6 percent say they have these wishes written down, Italians seem somewhat more willing than residents of the U.S. and Japan to place decision-making in the hands of doctors. Three in ten Italians (compared with about one in ten in the U.S. and Japan) say that doctors should have the greater say in which medical treatments to pursue for seriously ill patients who are near the end of their lives, while about half (compared with nearly 9 in 10 in the U.S. and Japan) say patients and their families should have the greater say.

In Italy, those with lower incomes and lower levels of education are more likely than their higher-income, more educated counterparts to say that doctors should have a greater say in these decisions. For example, 37 percent of Italians with less than a high school education say that doctors should have the greater say in medical decisions, compared with just 17 percent of university graduates.

Figure 33: Italians with Lower Levels of Income and Education More Likely to Say Doctors Should Have Greater Say in End-of-Life Decisions

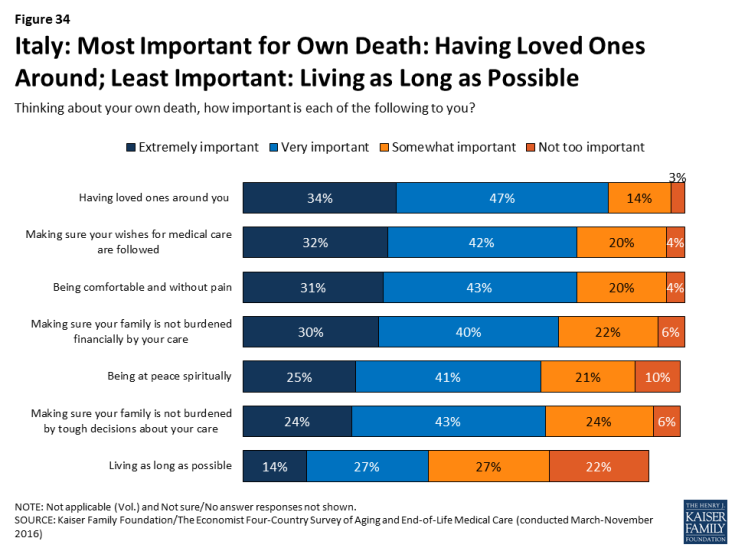

When it comes to priorities for their own death, Italians value the presence of loved ones along with a variety of other factors.

Asked what is important in thinking about their own death, a third (34 percent) of Italians say that having loved ones around is “extremely important.” Similar shares say the same about making sure their wishes for medical care are followed, being comfortable and without pain, and making sure their family is not burdened financially by their care. As in Japan, living as long as possible ranks far behind other factors, with just 14 percent saying it is “extremely important” to them.

Figure 34: Italy: Most Important for Own Death: Having Loved Ones Around; Least Important: Living as Long as Possible

Some other interesting demographic differences in views of end-of-life care in Italy are worth highlighting.

As in Japan, women in Italy are somewhat more likely than men to report having had a serious conversation with a loved one about their own wishes for end-of-life medical care (53 percent vs. 42 percent).

Catholics – who make up 75 percent of adults in Italy – are more likely than those with no religious preferences to say the health care system in Italy places too little emphasis on extending life (38 percent vs. 27 percent). By contrast, those with no religious preference are more likely than Catholics to say the health care system places too much emphasis on extending life (20 percent vs. 11 percent).

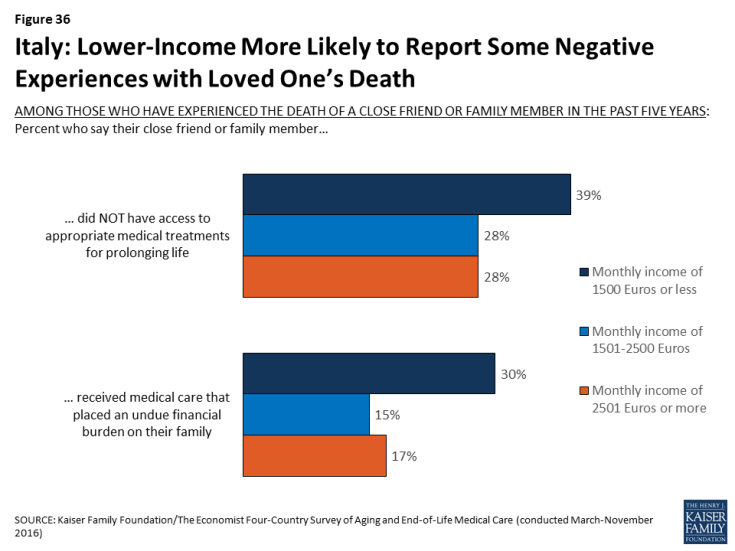

Among Italians with a loved one who died in the past five years, those with lower incomes are more likely to say their loved one received medical care that placed an undue financial burden on the family and less likely to say they had access to appropriate life-extending treatments.