Views and Experiences with End-of-Life Medical Care in Japan, Italy, the United States, and Brazil: A Cross-Country Survey

Country Highlights: Japan

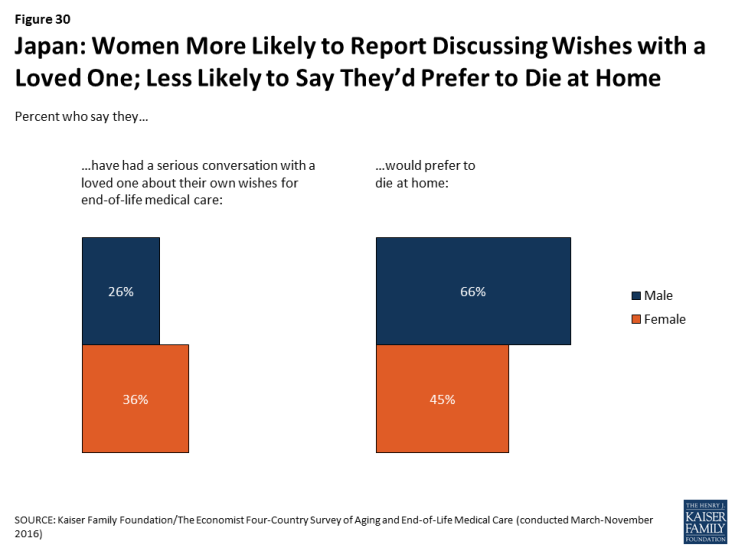

As the country in the survey with the oldest population, residents of Japan see the growing number of older adults as a major problem, and rate their health care system poorly on providing end-of-life care.

Nine in ten adults (91 percent) in Japan say the growing number of older people is a major problem for their country, far higher than any of the other countries surveyed. While just over half say it is the government’s responsibility to finance care for this aging population, one-third (35 percent) say the responsibility should fall on individuals and families. Japanese adults are also particularly sour on their health system when it comes to providing end-of-life medical care: seven in ten give it a rating of fair or poor on a 5-point scale.

Figure 23: Japan: Public Sees Aging of the Population as a Problem, Rates Health Care System Poorly When It Comes to End-of-Life Care

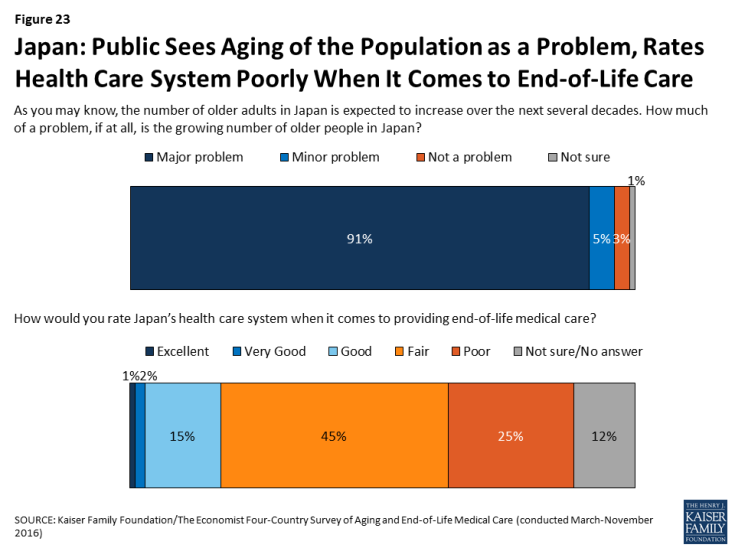

In Japan, a country with 13.4 hospital beds per 1,000 residents (roughly 4 times as many as any other country surveyed), residents are more likely than those in other countries surveyed to expect to die in a hospital and to say a loved one died in a hospital.

While just over half (55 percent) of Japanese adults say they would prefer to die at home, the majority (58 percent) think they are most likely to die in a hospital, higher than any of the other countries surveyed. Among residents with a loved one who died in the past five years, 69 percent in Japan say their loved one died in a hospital, while just 15 percent say they died at home.

Figure 24: Japan: Majority of Residents Expect to Die in a Hospital and About Seven in Ten Say Their Loved One Died in a Hospital

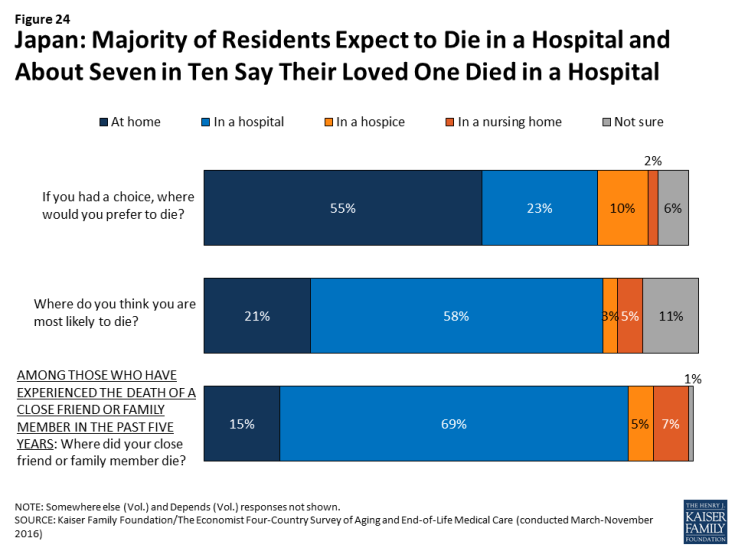

The top concern for Japanese adults in thinking about their own death is making sure their family is not financially burdened.

Six in ten (59 percent) adults in Japan say that making sure their family is not burdened financially by their care is “extremely important” in thinking about their own death. About half also place this level of importance on being at peace spiritually, not burdening their family with tough decisions about their medical care, having loved ones around, and being comfortable and without pain. By contrast, just 10 percent of Japanese adults say that living as long as possible is extremely important to them, ranking far below any other concern.

Figure 25: Japan: Most Important for Own Death: Not Burdening Family Financially; Least Important (By Far): Living as Long as Possible

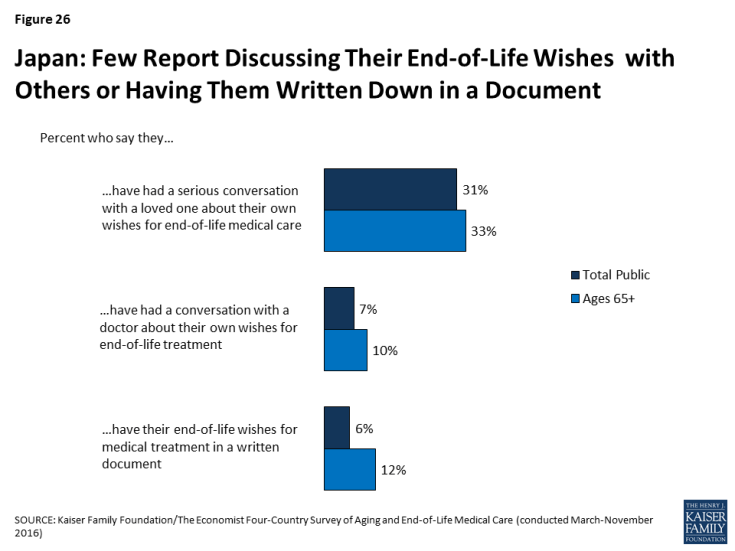

Conversations about end-of-life wishes are uncommon in Japan.

Just 31 percent of Japanese adults (and 33 percent of those ages 65 and over) say they’ve had a serious conversation with a loved one about their own wishes for end-of-life care. Just 7 percent say they’ve had such a conversation with a doctor and 6 percent say they have their wishes written down. Among those who don’t have their wishes in writing, two-thirds (64 percent) say they’ve never considered it, suggesting this is something that is not discussed or done often in Japan.

Figure 26: Japan: Few Report Discussing Their End-of-Life Wishes with Others or Having Them Written Down in a Document

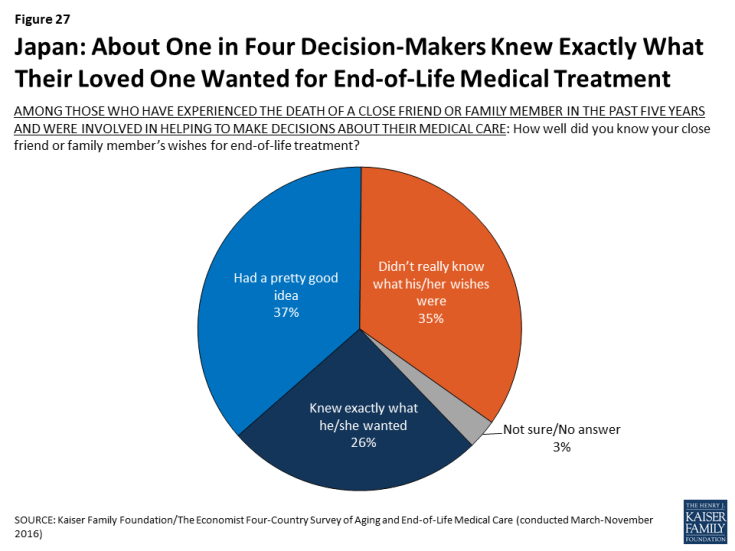

Perhaps reflecting this lack of conversation, just 26 percent of adults in Japan who served as a medical decision-maker for someone who died say they knew exactly what their loved one wanted in terms of medical treatment, substantially lower than among decision-makers in the other countries surveyed.

Figure 27: Japan: About One in Four Decision-Makers Knew Exactly What Their Loved One Wanted for End-of-Life Medical Treatment

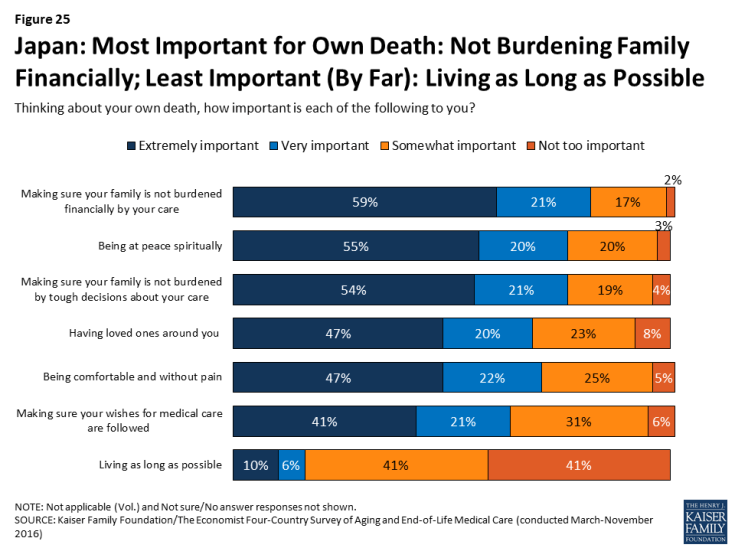

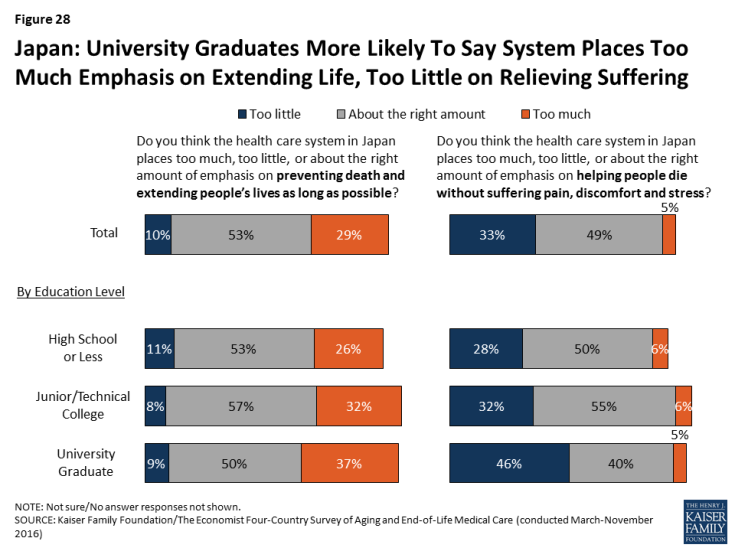

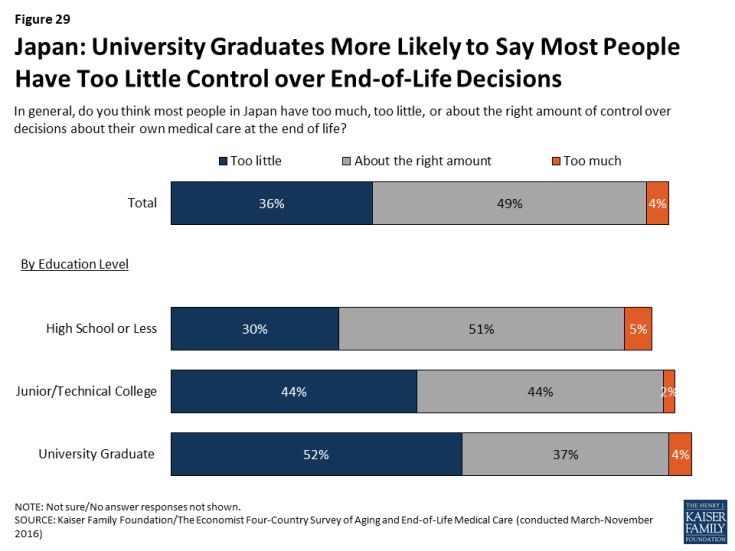

Some attitudes about end-of-life medical care in Japan differ by education level and gender.

University graduates in Japan are more likely than those with lower levels of education to say the health care system places too much emphasis on extending life and too little emphasis on helping people die without pain and stress. Those with higher levels of education are also more likely to say most people have too little control over decisions about their own medical care at the end of life.

Figure 28: Japan: University Graduates More Likely To Say System Places Too Much Emphasis on Extending Life, Too Little on Relieving Suffering

Figure 29: Japan: University Graduates More Likely to Say Most People Have Too Little Control over End-of-Life Decisions

In Japan, women are more likely than men to say they’ve had a conversation with a loved one about their wishes (36 percent vs. 26 percent). By contrast, Japanese men are more likely than women to say they’d prefer to die at home (66 percent vs. 45 percent).