The Future of Contraceptive Coverage

Contraceptive coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has made access to the full range of contraceptive methods affordable to millions of women. This provision is part of a set of services that has been identified by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) as key preventive services for women that are not addressed by the US Preventive Services Task Force or the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, entities that identified preventive services that must be covered without cost-sharing under the ACA. On December 20, 2016, HRSA issued updated coverage requirements, accepting in whole the recommendations of the Women’s Preventive Services Committee, which is comprised of representatives of national groups with expertise in women’s health. These updated recommendations continue to include contraceptive coverage.

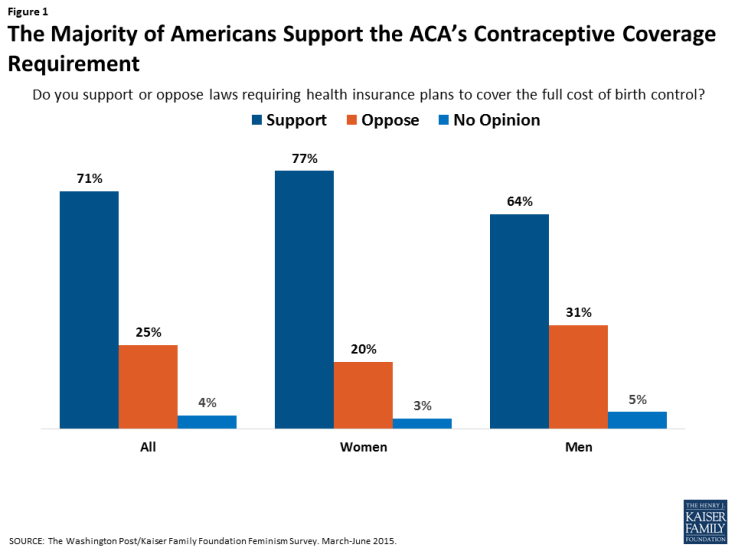

Since it was first issued in 2012, this provision has been controversial. While very popular with the public, with over 77% of women and 64% of men reporting support for no-cost contraceptive coverage (Figure 1), it has been the focus of litigation brought by religious employers, with 2 cases reaching the Supreme Court. As the Trump administration transitions to the White House, it remains to be seen specifically how or whether the new Administration and 115th Congress will address this particular provision. This brief explains the current contraceptive coverage rule, the impact it has had on coverage, and the potential state of coverage if the ACA rule is eliminated either through a full ACA repeal or administrative action.

What does the contraceptive coverage rule require plans to cover?

Starting in 2012, all new private plans were required to cover, without cost-sharing, the full range of contraceptives approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as prescribed for women, counseling and services.1 This provision applies to all non-grandfathered individual, small and large group, and self-funded plans. Grandfathered plans do not have to comply with this requirement or the other insurance reforms in the ACA.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued guidance in May 2015, which clarified that at least one form of all 18 FDA-approved methods of birth control must be covered without cost-sharing (Table 1). If a provider recommends a specific option or product, plans must cover it without cost-sharing as well. Insurers may use reasonable medical management, however, to limit coverage to brand-name drugs when a generic version exists, and can impose cost-sharing for equivalent branded drugs. Plans are required to have a “waiver” process for women who have a medical need for contraceptives otherwise subject to cost-sharing or not covered.2 In addition, plans must cover services such as contraceptive counseling, initiation of contraceptive use, and follow-up care, including management and evaluation, as well as changes to and removal or discontinuation of contraceptive methods.

| Table 1 : Minimum Contraceptive Coverage Requirements Clarified by HHS Guidance | |

| Contraceptive Method | Products/Options |

| Surgical sterilization | Also called tubal ligation |

| Implant sterilization | Only Essure available |

| Implantable Rod | Multiple |

| IUD – Copper | Only ParaGard available |

| IUD – Progestin | Multiple |

| Injection | Multiple |

| Oral contraceptives – combined | Multiple |

| Oral Contraceptives – progestin only | Multiple |

| Oral Contraceptives – extended/continuous use | Multiple |

| Patch | Multiple |

| Vaginal Ring | Only NuvaRing available |

| Diaphragm with Spermicide | Only Milex Omniflex available |

| Sponge with Spermicide | Only Today Sponge available |

| Cervical Cap with Spermicide | Only FemCap available |

| Female Condom | Multiple |

| Spermicide alone | Multiple |

| Emergency Contraception-Progestin | Multiple |

| Emergency Contraception- Ulipristal Acetate | Only ella available |

| SOURCES: FDA, Birth Control Guide and Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Treasury, FAQs about Affordable Care Act Implementation (Part XXVI). | |

What are the coverage requirements for employers?

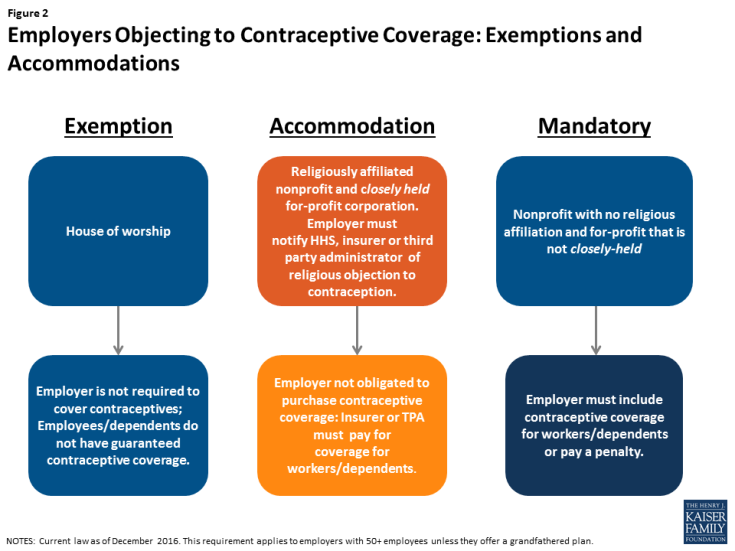

As the contraceptive coverage rules have evolved through litigation and new regulations, there are three categories of employers with differing requirements. Most employers are required to include the coverage in their plans. Houses of worship can choose to be exempt from the requirement if they have religious objections (Figure 2). This exception means that workers and dependents of exempt employers do not have coverage for either some or all FDA approved contraceptive methods, if their employer has an objection. Religiously affiliated nonprofits and closely held for-profit corporations are not eligible for an exemption, but may receive an accommodation. The Obama Administration originally crafted the accommodation to address the concerns of religiously-affiliated nonprofit employers, and then extended this same option to closely held for-profits after the Supreme Court ruling in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby. The accommodation allows these employers to opt out of providing and paying for contraceptive coverage in their plans by either notifying their insurer, third party administrator, or the federal government of their objection. The insurers then are responsible for covering the costs of contraception, which assures that their workers and dependents have contraceptive coverage, and relieves the employers of the requirement to pay for it.

While 10% of nonprofits with 5,000 or more employees have elected for an accommodation without challenging the requirement, this approach, however, has not been acceptable to all nonprofits with religious objections.3 Some are seeking an “exemption” from the rule, meaning their workers would not have coverage for some or all contraceptives, rather than an accommodation, which entitles their workers to full contraceptive coverage but releases the employer from paying for it. In May 2016, the Supreme Court remanded Zubik v. Burwell, sending 7 cases brought by religious nonprofits objecting to the contraceptive coverage accommodation back to the respective Courts of Appeal. The Court instructed the parties to work together to “arrive at an approach going forward that accommodates petitioners’ religious exercise while at the same time ensuring that women covered by petitioners’ health plans receive full and equal health coverage, including contraceptive coverage.”4 In July 2016, the Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS), Labor and Treasury issued a Request for Information (RFI) inviting public comments on “whether there are alternative ways (other than those offered in current regulations) for eligible organizations that object to providing coverage for contraceptive services on religious grounds to obtain an accommodation, while still ensuring that women enrolled in the organization’s health plans have access to seamless coverage of the full range of Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptives without cost sharing.” The Obama Administration asked the courts to delay any action on the cases while they review the over 50,000 comments submitted. The next case status reports with the courts are due after the transition to the Trump Administration. It is not clear whether the Trump Administration will continue to defend these lawsuits, maintain the current regulations, or change the rules for employers with objections to contraceptive coverage. The Trump campaign supported expanding the exemption for nonprofits with religious objections, and incoming Secretary of Health and Human Services, Tom Price, stated in 2012, that he felt the contraceptive coverage requirement infringes on religious liberties.56

How has the contraceptive coverage rule affected women?

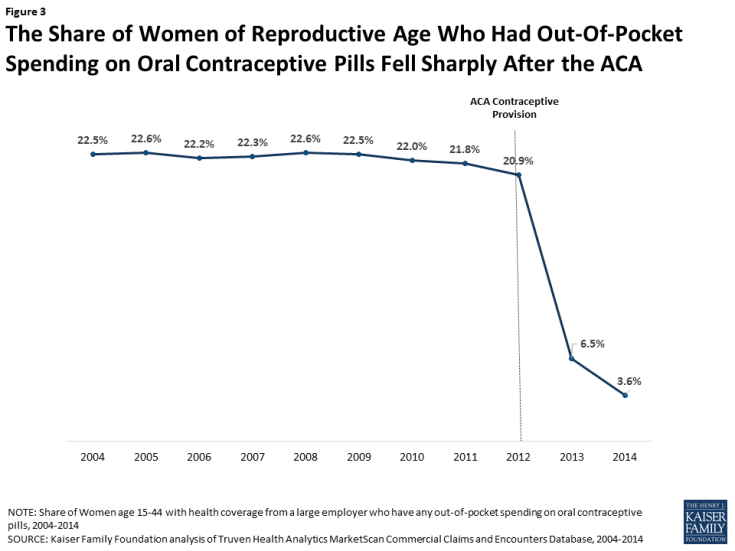

Contraceptive use among women is widespread, with over 99% of sexually-active women using at least one method at some point during their lifetime.7 Contraceptives make up an estimated 30-44% of out-of-pocket health care spending for women.8 Since the implementation of the ACA, out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs has decreased dramatically (Figure 3). The majority of this decline (63%) can be attributed to the drop in out-of-pocket expenses on the oral contraceptive pill for women.9 One study estimates that roughly $1.4 billion dollars per year in out-of-pocket savings on the pill resulted from the ACA’s contraceptive mandate.10 By 2013, most women had no out-of-pocket costs for their contraception, as median expenses for most contraceptive methods, including the IUD and the pill, dropped to zero.11

Figure 3: The Share of Women of Reproductive Age Who Had Out-Of-Pocket Spending on Oral Contraceptive Pills Fell Sharply After the ACA

This provision has also influenced the decisions women make in their choice of method. After implementation of the ACA contraceptive coverage requirement, women were more likely to choose any method of prescription contraceptive, with a shift towards more effective long-term methods.12 High upfront costs of long-acting methods, such as the IUD and implant, had been a barrier to women who might otherwise prefer these more effective methods. When faced with no cost-sharing, women choose these methods more often13, with significant implications for the rate of unintended pregnancy and associated costs of childbirth.14

Finally, decreases in cost-sharing were associated with better adherence and more consistent use of the pill. This was especially true among users of generic pills. One study showed that even copayments as low as $6 were associated with higher levels of discontinuation and non-adherence,15 increasing the risk of unintended pregnancy.

If the contraceptive coverage rule is modified or eliminated, are there other federal rules and state laws that affect coverage?

More than half of women in the United States are insured through an employer-sponsored plan, either as the primary beneficiary or as a spouse or dependent. In 2000, a ruling by the Employment Equal Opportunity Commission (EEOC) found that employers that covered preventive prescription drugs and services, but did not cover prescription contraceptives, were in violation of the Civil Rights Act.16 The EEOC reasoned that failure to cover contraception constituted sex discrimination under Title VII and the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, which prohibits discrimination against women based on their ability to get pregnant. This ruling, however, did not address the issue of cost-sharing, nor the scope of coverage.

Prior to the passage of the ACA and the contraceptive coverage requirement, the 2010 Kaiser/HRET survey of employers found that 85% of large firms covered prescription contraceptives in their largest health plans17, although they may have used cost-sharing and were not required to cover the full scope of contraceptive care, the amount of which can vary greatly by employer and type of plan. If the ACA contraceptive coverage rule is modified or eliminated, any requirement for the coverage of contraceptives without cost-sharing will fall back to the states. State laws, however, only apply to state regulated plans, not self-funded plans where 61% of covered workers are insured.18 In self-funded plans, the employer assumes the risk of providing covered services and usually contracts with a third party administrator (TPA) to manage the claims payment process. These plans are overseen by the Federal Department of Labor under the Employer Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA).

States have historically regulated insurance, and many have mandated minimum benefits for decades. Contraceptive coverage is no exception. Currently, 28 states require insurance plans to cover contraceptives, with a wide range of coverage and cost-sharing requirements, and exemptions among these mandates.19

Since the passage of the ACA, four states have strengthened and expanded the federal contraceptive coverage requirement. In 2014 California passed the Contraceptive Coverage Equity Act of 2014, which requires private and Medicaid managed care plans to cover all prescribed FDA-approved contraceptives for women without cost-sharing. Maryland enacted a very similar law in 2016, and it will go into effect in January 2018. Vermont also passed a similar law (effective January 2017) that applies to all health insurance plans, as well as coverage offered through Medicaid and all other public programs offered by the State. Illinois’s law, (effective January 2017) requires plans to cover all contraceptive methods, including all over-the-counter methods except male condoms, without cost-sharing.

While contraceptive coverage without cost-sharing will remain intact for fully insured plans in these 4 states, regardless of what happens with the ACA rule, state laws do not have jurisdiction over self-funded plans, under which many women are insured.

Conclusion

For the first time, the ACA set federal preventive services rules, including no-cost contraceptive coverage, for all insurance plans. If the Trump Administration modifies or eliminates the ACA contraceptive coverage rule, scope of coverage will depend on where a woman lives, where she works, and her insurance plan. Millions of women could lose no-cost coverage for the full range of contraceptive methods. Insurance companies and employers will be the ones to make choices about coverage and cost-sharing. For some women, their choices will be limited, and some of the most effective and costly methods will be out of financial reach.