Money Follows the Person: A 2013 State Survey of Transitions, Services, and Costs

Key Findings

Transitions

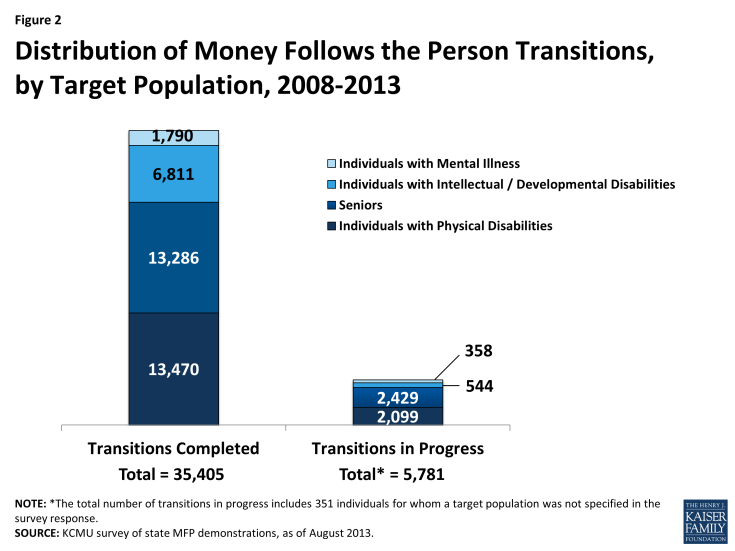

As of August 2013, over 35,400 Medicaid beneficiaries had enrolled in MFP and another 5,781 transitions were in progress (Figure 2). Three states (OH, TX, and WA) made up 40 percent of all MFP transitions, with Texas accounting for the most cumulative transitions (7,307 or 21%). Variation in program size reflects, among other things, the length of program operation, the size of the eligible population in each state, and state capacity and experience in operating transition programs.

Among the 42 MFP demonstrations that are currently operational, nine states became operational in 2012 (ME, MS, NV, and VT) or 2013 (AL, CO, MN, SC, and WV) and transitioned a combined total of 227 individuals, as of August 2013. Similar to when the first MFP grantee states became operational, new grantees are finding that it takes time to receive CMS approval of their operational protocol and to begin transitions once the demonstration is operational. Therefore, these states have set relatively modest transition goals for their first few years of the demonstration.

The majority of MFP participants to date are individuals with physical disabilities (38%) and seniors (38%). One in five MFP participants (19%) is an individual with an intellectual/developmental disability (I/DD). Individuals with mental illness (5% of total transitions) and those with I/DD are less likely to be candidates for transition due to their typically more extensive medical and LTSS needs. Seniors and people with physical disabilities also lead the number of transitions in progress.

Over the past three years, states reported taking steps to increase the number of transitions among individuals with mental illness. Twenty-six states reported efforts underway to increase transitions among this population, slightly down from the 29 states that reported targeting those with mental illness in 2012. Ohio’s state Medicaid agency has transitioned the largest number of MFP participants with mental illness (1,100) by working closely with the state’s Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. Recently, Ohio began a program called “Recovery Requires a Community” that provides supplemental resources for individuals with serious and persistent mental illness who are living in an institutional setting and desire to live in the community; most individuals will enter the program after participating in HOME Choice (Ohio’s MFP demonstration) and the program provides additional independent living resources for individuals beyond the one-year MFP period.

State Medicaid agencies reported actively coordinating with their state Behavioral Health/Mental Health Departments and collaborating with community mental health providers to provide interdisciplinary services and community supports for people with mental health needs to successfully transition to the community. Other current state efforts to target this population include the following: education for mental health providers about MFP and available community-based supports, inclusion of MFP staff on states’ Institutions for Mental Disease discharge planning teams, identification of children living in psychiatric residential treatment facilities who could transition to the community, collaboration with CMS to amend the state MFP operational protocol to include individuals with mental illness as a target group, launch of a pilot program with the Balancing Incentive Program (BIP)1 to target individuals with mental illness specifically, and development of a Section 1915(i) state plan amendment2 to cover individuals with mental illness who need HCBS and who had not previously been eligible for Medicaid. Fifteen states reported no specific plans to target this population.

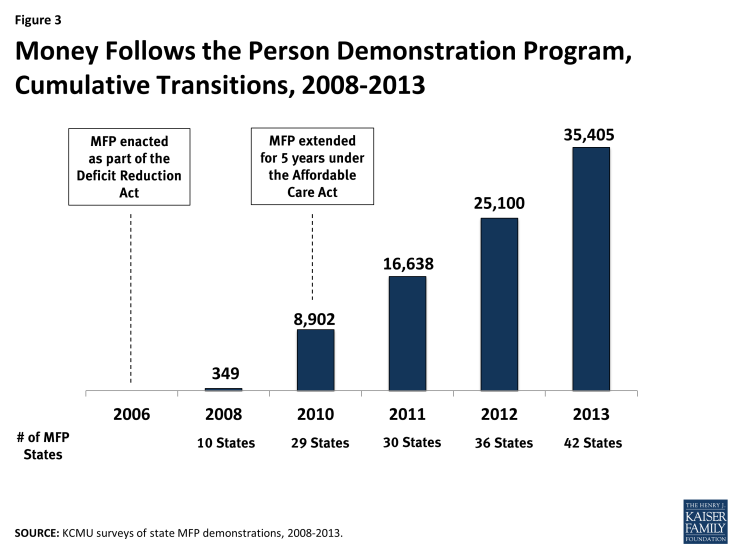

Over 10,300 Medicaid beneficiaries returned to community residences from institutions through the MFP demonstration between 2012-2013. Despite a slow start for several states, MFP grantees averaged over 9,000 transitions per year over the past two years. In 2012, states were behind their original enrollment projection of 38,000 individuals; 2013 enrollment numbers show they are nearing that original transition projection.3 In 2012, states reported transitioning nearly 25,000 individuals back to the community cumulatively, up from almost 17,000 individuals in 2011 (Figure 3). With the addition of 15 new MFP demonstrations since 2011 (all except two of those states are currently operational), more Medicaid beneficiaries are getting the opportunity to transition from an institutional setting to community-based living with person-centered, pre- and post-transition supports and services in place. Four states (AK, AZ, UT, and WY) have chosen not to apply for an MFP demonstration, one state (FL) was awarded an MFP grant and is no longer active, and one state (NM) began the application process but decided not to move forward.

The 2013 survey asked states to report if they were on pace with their annual transition targets, and most (26 states) reported that they were on target to meet annual goals.4 Seventeen states reported that they were not on pace to meet their annual projections. States’ modest start with MFP transitions can be attributed to, for example, implementation delays and/or challenges related to transitioning populations with multiple chronic and disabling conditions. States reported a number of other contributing factors including the following: lack of affordable, accessible housing options particularly for individuals with complex medical and LTSS needs, a shortage of state MFP staff, and successful diversion programs that reduce institutional admissions.

Despite these challenges, 34 states expect their MFP enrollment to increase over the next year, while nine states anticipated no change in annual enrollment. No state anticipated a decrease in enrollment. State efforts to increase outreach and enrollment include hiring outreach coordinators, using the Minimum Data Set (MDS)5 to assist with targeted outreach, using peer-to-peer outreach to NF residents, collaborating with the state Long-Term Care (LTC) Ombudsman program, forming MFP stakeholder groups and/or advisory commissions, and educating formal and informal LTC providers and beneficiary advocates about MFP. Other selected outreach examples are highlighted below.

Illinois developed a web-based referral process for individuals, family members, and NF staff to directly refer individuals to its MFP program. The online referral form is located on the state’s MFP website and provides for greater accountability and tracking of referral follow-up activities through a centralized process. The Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services distributed a notice to all NFs outlining the online referral process in Spring 2013 and the number of referrals dramatically increased over six months that followed as awareness of the web-based system grew.

Nebraska’s MFP program implemented a media campaign in July 2013. The state has contracted with a television station that runs a commercial spot numerous times each month.

New Jersey recently re-branded its program as “I Choose Home-NJ.” The state is implementing a new marketing and outreach plan featuring strategies for facility-based marketing and education as well as focused messaging for the larger community that will include radio spots, letters to the editor, newspaper articles, an infographic for policy makers, and a press conference.

Outreach, Referrals, and Transition Support

Thirty-six states reported partnering with local Aging and Disability Resource Centers (ADRCs) to assist with MFP program referrals and to help coordinate transitions. Within a state, outreach and enrollment efforts are often accomplished through partnership efforts between the Medicaid program and other state agencies, community stakeholders, and MFP staff. The ACA appropriated $10 million a year for five years (2010-2014) to expand ADRCs to serve as community access points for individuals seeking information and referrals for LTSS. Coordinators at ADRCs that receive funding from state MFP demonstrations can assist with processing referrals from MDS 3.0, Section Q-Participation in Assessment and Goal Setting and MFP outreach and enrollment, including options counseling, MFP program eligibility verification, and HCBS waiver slot distribution to prospective MFP participants. Several states reported using MFP funds to expand ADRC activities in the year ahead. For example:

Illinois received funding to employ three Transition Engagement Specialists at three ADRCs in locations where individuals with serious mental illness can access MFP benefits. The specialists are charged with engaging potential MFP participants through cross-population outreach activities, building relationships with NF administrators and staff, assisting in the development of best practices related to MDS 3.0 Section Q referral processes, and improving the overall accuracy of referrals to the MFP program, including triaging referrals to determine which community agency is most appropriate to carry out follow-up processes with NF residents. Illinois’ MFP population is very complex, with almost half of MFP beneficiaries having five or more chronic health conditions in addition to a serious mental illness.

In Ohio, organizations in the ADRC network serve as local contact agencies and staff are called Community Living Specialists. These specialists use the Community Living Plan Addendum to assess the needs of individuals residing in NFs or other institutions when they are identified by the MDS 3.0 Section Q referral process as having a desire to reside in the community. Ohio is currently developing an electronic version of its assessment, which will allow for greater efficiency in follow-up interview assignment, outreach activity tracking, online data entry, and online interview approval. In addition, by integrating data validity checks, the state hopes to increase the quality of the data obtained.

Participant Characteristics

- This year’s survey included questions related to characteristics of MFP participants. Where possible, states were asked to report responses by target population. Across all MFP demonstrations, state officials reported the following results:

- The average age of MFP participants was 58 years old. MFP participants with I/DD were younger (on average

- 46 years old) than individuals with a mental illness or a physical disability, who averaged 49 and 51 years old, respectively. The average age of senior MFP participants was 76, up from an average age of 71 in 2011 and 75 in 2012.

- MFP participants averaged 3.5 months to transition back to the community – the same length of time that states reported in 2012. Individuals with mental illness or I/DD took longer to transition home compared to seniors and people with physical disabilities.

- MFP participants most often transitioned to an apartment. Seniors were more likely to transition back to a house (their own house or a family member’s house) or an apartment, whereas individuals with I/DD more often transitioned to a small group home.

- The average reinstitutionalization rate was 11 percent. In both 2011 and 2012, states reported an 8 percent reinstitutionalization rate. Reinstitutionalization is defined as returning to a NF, hospital, or Intermediate Care Facility for Individuals with Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities, regardless of length of stay, during the beneficiary’s MFP participation year. Across all target populations, seniors were most likely to be reinstitutionalized, and individuals with I/DD were the least likely to return to an institutional setting.

MFP helps dual eligible beneficiary overcome amputation challenges and return to independent living

Vera, 76, suffers from peripheral vascular disease and diabetes. Complications from both conditions resulted in a leg amputation. Following the surgery and hospitalization, Vera needed 24-hour care and moved into a nursing home. Vera qualified for Medicaid during her nursing home stay and within eight months moved back to the community as a participant in the Medicaid MFP demonstration.

Vera was able to locate and secure a first floor apartment that was both physically accessible and affordable on her limited Social Security income. Vera receives six hours of personal care services every day, except on weekends when her family comes to help her. She relies on five prescription drugs a day, including insulin to manage her diabetes. She takes the bus to doctor visits and twice weekly physical therapy sessions. Vera explained, “It’s easy to get around with my [wheel]chair now that I am in a lower level apartment” and said that there are no real challenges to being home.

“Without Medicaid, I don’t know where I would be.”

– Vera, Tennessee

To read more of Vera’s story see Molly O’Malley Watts et al., “Money Follows the Person Demonstration Program: Helping Medicaid Beneficiaries Move Back Home,” April 2014, available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/money-follows-the-person-demonstration-program-helping-medicaid-beneficiaries-move-back-home/.

Benefits

Access to comprehensive pre- and post-transition MFP services enables Medicaid beneficiaries with a range of chronic and disabling conditions to successfully transition back to the community. States provide a comprehensive set of benefits to MFP participants, including those services provided under existing HCBS waivers and state plan benefits packages as well as MFP demonstration services and supplemental services, to ensure successful transition back to the community. Services that qualify for the MFP enhanced federal matching rate during a beneficiary’s MFP participation year are those waiver and state plan services that will continue once the individual’s MFP demonstration transition period has ended. Forty-three states currently offer home and community-based waiver services to MFP participants, and 34 states offer HCBS to MFP participants under their state plan benefits package. Common Medicaid HCBS are case management, homemaker services, home health aide services, personal care services, adult day health care, habilitation, and respite care.

Thirty-seven states offered MFP demonstration services in 2013, which are additional Medicaid HCBS reimbursed at the enhanced MFP federal matching rate during a beneficiary’s 12-month MFP participation period. MFP demonstration services are provided in a manner or amount beyond what a typical Medicaid HCBS beneficiary receives and are not otherwise available to a non-MFP Medicaid beneficiary. For example, a state that does not normally offer caregiver training might make such services available to caregivers of MFP participants. After the beneficiary’s transition year ends, states are not obligated to continue MFP demonstration services but may choose to fund them through Medicaid at the state’s regular federal matching rate.

Eighteen states offered MFP supplemental services – which are not necessarily LTC in nature – in 2013. MFP supplemental services are only offered during the beneficiary’s demonstration transition year and are reimbursed at the state’s regular federal matching rate. Sixteen states reported offering both demonstration and supplemental services. States design MFP demonstration and supplemental services to ensure participants’ successful transition back to community living. These services include benefits such as transition coordination, coverage of one-time housing expenses (such as security deposits, utility deposits, and furniture and household set up costs), assistive technology, employment skills training, 24-hour back-up nursing, home-delivered meals, peer-to-peer community support, and LTC ombudsman services.

The 2013 survey asked states to report if MFP services were modified or added to the benefit package over the past year. Nineteen states reported no difference in the services offered to MFP participants, and 14 states reported making changes in 2013. Of the states reporting benefit alterations, 12 reported increasing services, with the remaining states reporting a decrease in services or a neutral change. Selected examples of state modifications to benefits are:

- The District of Columbia added two new demonstration services: peer counseling and enhanced primary care coordination.

- Georgia added three new demonstration services: life skills coaching, home inspection (pre and post-transition), and supported employment.

- Ohio added pre-transition case management services and increased transition coordination services through the beneficiary’s 90th day of enrollment. These changes were intended to increase communication and collaboration among providers with the goal of better addressing the participant’s needs once she transfers to the community.

- North Dakota added transition adjustment support (“educational supervision”) to provide supervision and instruction to NF residents preparing to transition to the community and live independently.

- Vermont added adult family care homes as a new waiver service.

Many of the services offered under MFP are geared toward meeting the needs of Medicaid beneficiaries with complex health conditions and physical limitations. Notable services offered to ensure that such persons transition home safely include personal emergency response systems, trial overnight stays, and roommate matching services. Employment for people with disabilities, including MFP participants, also can help to ensure a successful transition from institutional to community living. States are offering supported employment services to MFP participants, although only a small share use them.6 Examples of these employment services include the following: non-medical transportation services, pre-vocational services, employment skills training, job coaching, vehicle modifications, and adaptive equipment which may include medical supplies or augmentative communication devices. New Jersey and Texas hired employment specialists, using MFP administrative funds, to assist participants with identifying goals and securing employment.

Beneficiary self-direction of services is an option in most MFP demonstrations, but participation rates are low and vary across states.Forty states offer or have plans to offer Medicaid beneficiaries the authority to make decisions about some or all of their services. Only four states responded that self-direction was not a component of their MFP demonstrations. Self-direction is an alternative to the provider management service delivery model. Self-direction promotes personal choice and control over the delivery of services, including who provides services and how they are delivered. For example, an MFP participant may be given the opportunity to recruit, hire, and supervise direct service workers. Participants may also have decision-making authority over how the Medicaid funds in a budget are spent.

An estimated 19 percent of MFP participants self-directed at least some of their services in 2013. Three states reported nearly 100 percent participation in self-direction (DE, OH, and SC) due to the fact that one-time home set-up funding was categorized as a self-directed service. Seventeen states reported the percentage of MFP participants who self-direct services to be 5 percent or less. Nine states reported an increase in the percentage of MFP participants who utilized self-directed options over the past year. Twenty-four states reported no change in the percentage of MFP participants who self-direct and one state reported a decrease.

Financing

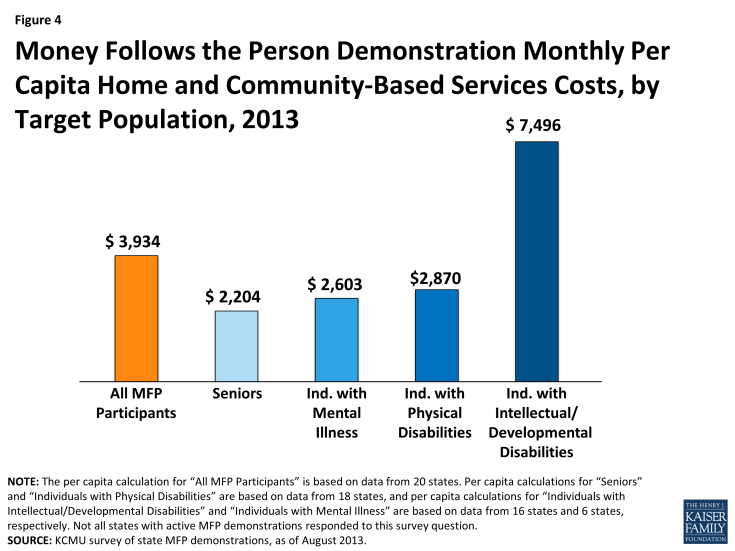

The average monthly per capita cost of serving an MFP participant in the community was $3,934 in 2013 (Figure 4). States were asked to report average monthly per capita costs for MFP participants, which ranged from a high of $10,528 to a low of $1,299 per person per month, based on responses from 20 states. Differences in per capita costs may be attribu table to differences in MFP-covered services across states and/or a reflection of the diverse needs of the target populations. In comparison, the national average per user spending on Medicaid HCBS only, including Section 1915(c) waivers and the home health and the personal care services state plan benefits and excluding other Medicaid-covered services, was $16,673 in 2010; there was great variation among states and across programs.7 As with HCBS waiver expenditures, MFP states that transitioned a greater number of individuals with intellectual/developmental disabilities (I/DD) had higher per capita costs since these individuals have extensive medical and LTSS needs. Average MFP monthly costs were highest for people with I/DD ($7,496) followed by individuals with physical disabilities ($2,870), individuals with mental illness ($2,603)8 and seniors ($2,204). These per user per month costs are comparable with the costs reported by Mathematica Policy Research in their 2012 evaluation of the MFP demonstration.9

Figure 4: Money Follows the Person Demonstration Monthly Per Capita Home and Community-Based Services Costs, by Target Population, 2013

When asked to compare per capita costs for MFP participants with per capita costs for other Medicaid beneficiaries receiving HCBS, 13 states said costs were comparable, seven states reported that per capita costs were lower for MFP participants, and six states reported per capita costs were higher for MFP participants. The remaining states did not answer this survey question.When asked to compare the per capita LTC costs for Medicaid beneficiaries who reside in institutions to per capita LTC costs for MFP participants, 26 states reported that per capita costs were lower for MFP participants. No state reported that the two costs were comparable or that institutional care was lower.

Quality

States are using information obtained through the CMS MFP Quality of Life (QoL) Survey, quality management reviews, and critical incident reports to improve their MFP demonstrations. States identified the QoL survey as their main tool to measure quality and satisfaction among MFP participants. MFP grantees are responsible for the survey administration, data entry, tracking, quality assurance, and transmission of data to CMS. Nursing facility residents are asked to complete the QoL survey within 30 days prior to leaving the institution and again at one and two years post-transition. The QoL instrument captures the participant’s views on the following: (1) life satisfaction, (2) quality of care, and (3) community life. A national evaluation of QoL survey responses found that most participants fare well in the community and have enjoyed an improved quality of life in comparison to their quality of life in an institution. Gains in quality of life were largely maintained among beneficiary’s still residing in the community one year post-MFP participation, and, in some cases, previous MFP participants reported continued improvements such as greater access to personal care and community integration services10 Additionally, states reported that traditional quality standards – Medicaid LTC quality improvement and quality assurance processes that are in place through Section 1915(c) waivers and state plan assurances – are also applied to the MFP program.

MFP helps dually eligible beneficiary with a physical disability move home and return to work

One morning in February 2009, during a heavy snowstorm, Chuck, 60, slipped on ice and ruptured several discs in his back. Several months later, Chuck had back surgery and developed a blood clot. Following surgery to remove the blood clot, he was admitted to a nursing home where he lived for three years.

In April 2013, Chuck left the nursing home and moved in with his brother. As an MFP participant, Chuck obtained a chair lift, a wheelchair, a hospital bed, a shower chair, and a one-time allocation of $700 to purchase personal household goods. He relies on the help of a full-time personal care attendant, receives therapy in his house, and takes six prescription drugs daily for pain, muscle spasms, and high blood pressure.

Chuck spends his days working from home as a telemarketer. He desires to have his own place and has been on a housing waiting list for several years.

“[Without Medicaid], I would have few options in life.”

–Chuck, Maryland

To read more of Chuck’s story see Molly O’Malley Watts et al., “Money Follows the Person Demonstration Program: Helping Medicaid Beneficiaries Move Back Home,” April 2014, available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/money-follows-the-person-demonstration-program-helping-medicaid-beneficiaries-move-back-home/.

In addition to the QoL survey, all MFP states must complete the following quality-related requirementsdevelop risk assessment and mitigation processes, which are reviewed by CMS and must be approved prior to MFP program implementation; (2) complete a review of 24-hour emergency back-up services; and (3) develop a critical incident report management system. States review incident reports to identify potential issues post-transition that may warrant changes to current systems. Several states, such as North Dakota, employ a quality assurance specialist to oversee MFP quality initiatives. Georgia convenes a quarterly evaluation team meeting to review results of the CMS QoL survey. Illinois uses the University of Illinois (UIC) at Chicago, College of Nursing to serve as the quality assurance vendor for its MFP program. In addition to advanced nurse consultation, case consultation, and data analysis, UIC also provides numerous quality reports to state MFP staff to inform policy decisions. In 2013, the state requested that UIC conduct an analysis of beneficiary sustainability in the community, specifically focused on identifying the characteristics associated with sustainability in the community during the participation period and the characteristics associated with reinstitutionalization.

Other quality measures reported by states include providing intensive case management during the entire MFP participation year and offering transition coordination services until 90 days post-transition. West Virginia is using transition navigators to follow MFP participants for the 365 days post-transition. The transition navigators contact beneficiaries on a monthly basis to review the individualized transition and risk mitigation plans to ensure that services and supports are being provided according to the participant’s plan of care and address any quality-related issues that may arise.

Issues Facing MFP in 2013 and Beyond

Linking MFP participants to safe, affordable, and accessible community-based housing options remains a critical focus for state and federal officials. Twenty states (down from 27 states in 2012) reported housing to be the most significant issue facing MFP in the year head. Since the first Medicaid beneficiary transitioned to the community as an MFP participant in 2008, states have been challenged to meet the housing need for Medicaid beneficiaries interested in transitioning back to the community. These beneficiaries often have ongoing and persistent cognitive and physical impairments and chronic conditions that result in the need for assistance with activities of daily living and also lack adequate income and resources to afford fair market rent on their own. To address housing shortages and to improve the communication between state Medicaid agencies and state housing agencies, 30 states have hired housing coordinators (or housing specialists) who assist individuals interested in transitioning with locating and securing housing. States such as Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, and Washington employ multiple housing coordinators to improve outreach and coordination efforts, help link MFP participants to housing resources, and assist in LTSS rebalancing efforts. Often, housing coordinators will help individuals find housing and negotiate lease terms with landlords. States are also focused on lessening the amount of time it takes to transition individuals back to the community. In the year ahead, states will continue efforts to identify additional housing subsidies or vouchers while also building capacity for more community-based providers and services.

Other key housing strategies employed include offering expanded environmental modifications, offering assistance with rent and security deposits as a demonstration service, and partnering with state housing authorities and the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to secure subsidized housing for seniors and people with disabilities. Several states noted that they recently applied for and/or received funding through the HUD Section 811 grant program to provide interest-free capital advances and operating subsidies to nonprofit developers of affordable housing for people with disabilities and project-based rental assistance. The following are additional examples of state initiatives to increase the supply of affordable housing options:

- Maryland cited continued education and advocacy as the key steps towards an increased supply of safe, affordable, accessible housing. The Real Choice System Change grant from CMS allowed MPAH (Maryland Partnership for Affordable Housing), a government agency, to successfully create an inter-agency agreement between the state Departments of Housing and Community Development, Health and Mental Hygiene, and Disabilities. MPAH and representatives from each agency worked together to submit an application for HUD’s Section 811 Project Rental Assistance (PRA) demonstration program and in February 2013, Maryland was awarded $10.9 million. MPAH is dedicated to developing infrastructure, including coordination of services and supports between agencies, as well as an efficient and timely unit referral system as required by the Section 811 PRA program. As part of the Section 811 application, several public housing authorities (PHAs) committed to set aside a total of 102 vouchers for people with disabilities age 62 or younger. (For more information about Maryland’s MFP Program, please see the companion case study.)

- Delaware has a web-based housing database that beneficiaries, case managers, and family members can use to search for community-based housing options.

- Wisconsin provides housing counseling as a relocation service under its HCBS waivers.

- Illinois hired three housing coordinators to improve outreach, coordination, and linkages to housing resources and assistance in LTC rebalancing efforts. They are responsible for assuring the Statewide Housing Referral Network operates smoothly and that referrals to housing providers are made promptly. Illinois also has a housing locator website with a special caseworker portal that provides detailed information on available housing options and accessibility information.

- The New Jersey Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency, Department of Community Affairs, and Department of Human Services, Division of Developmental Disabilities have launched the Special Needs Housing Partnership Loan Program (SNHPLP) aimed at creating affordable, supportive housing for people with I/DD. The SNHPLP will provide financing to create permanent supportive housing and community residences. As of September 2013, the SNHPLP had 60 beds committed, 30 projects in development, and 18 projects in the pipeline in nine counties and 19 municipalities in the state.

HCBS Providers

Two-thirds of MFP states reported an adequate supply of direct care workers in the community in 2013. States recognize that workforce initiatives are a critical component of successful community-based transition programs and are actively addressing challenges such as high turnover rates and shortages of direct service workers in rural settings. Most state efforts in this area are intended to strengthen the capacities of direct support professionals and elevate their standing as professionals (i.e., compensation, benefits, and authority). Examples of workforce development strategies adopted by states include: maintenance of a direct service worker registry website, promotion of Medicaid beneficiaries hiring family caregivers through the self-directed option, and use of MFP administrative funds for direct service workforce training. Several states have developed a standard training curriculum and certification process that can be used by HCBS providers and educators to enhance the pool of qualified and well-trained direct care staff. Texas reported accessing MFP funding for data collection (survey) of direct service workers as well as an employer/employee matching database. North Dakota has a workforce coordinator who partners with those in need of workforce development by marketing direct service work, coordinating training and options for career development, and supporting the current workforce with the goal of retention.

Tennessee is working on a workforce development project in conjunction with Lipscomb University’s School of TransformAging. The first goal of this initiative is to develop and implement a statewide, standardized competency-based training and certification program for HCBS non-medical direct care staff. In addition, the state is implementing a purchasing initiative that will restructure Medicaid payments made by contracted managed care organizations (MCOs) for NF services and core HCBS. A set of quality domains and performance measures will be developed for core HCBS – primarily those services that include hands-on assistance with activities of daily living. A modified reimbursement structure for these services will align payment rates with performance on the specified quality measures, incentivizing direct care providers to provide high quality, person-centered care.

Cost Containment

Although cost containment remains a priority for state Medicaid programs, MFP demonstrations were largely spared from cuts related to recent fiscal pressures. Thirty-six states reported that cuts to MFP did not occur over the previous year or were not likely to occur at the time of the survey. Only five states reported experiencing or anticipating cutbacks due to fiscal pressures that would affect their MFP demonstrations. One state reported a negative impact on potential MFP participants when, as a result of the federal budget sequestration, remaining federal funding for MFP Housing Choice Vouchers set aside for the I/DD population was cut with no guarantee that it would be restored. Another state noted that fiscal shortfalls and budget reductions impacting Medicaid for the past few years has resulted in no new investment in HCBS waivers, especially for the I/DD population; this has led to lower MFP transition targets.

Expansion of LTSS Under the ACA in MFP States

Forty MFP states have implemented or have plans to implement at least one new ACA LTSS option as of August 2013. The ACA included a number of new and expanded options that offer states the ability to take advantage of enhanced federal funding to re-orient their delivery of LTSS toward HCBS and away from institutional care. Many states are pursuing or have plans to pursue multiple ACA LTSS options, either separately or in combination. (For more information about state’s take-up of the options, please see the Kaiser Family Foundation’s State Health Facts website.) As of August 2013, 24 MFP states reported plans to take-up the Section 1915(i) option (12 states operational; 12 states planning), which allows states to provide HCBS as an optional benefit under their state Medicaid plan instead of through a waiver. Twenty-three MFP states reported plans to operate a health homes initiative, a new approach to manage care for people with chronic illnesses which provides states with an enhanced 90 percent federal matching rate for health home services during the first two years that a health home state plan amendment is in effect.11 At the time of the survey, 13 states’ health home initiatives were operational, and nine states were in the planning process. Twenty-two MFP states are pursuing BIP (16 states operational in August 2013; 6 states planning), which provides financial incentives (i.e., 2% or 5 % federal matching rate increase) to states that were devoting less than half of their LTC spending to HCBS and undertake structural reforms to increase access to community-based LTSS as an alternative to institutional care. Twenty MFP states reported pursuing new state demonstrations to align financing and integrate care for dually eligible beneficiaries (9 states operational; 11 states planning). Thirteen MFP states reported interest in taking up the Section 1915(k) Community First Choice state plan option (CFC) (3 states operational; 10 states planning), which provides a 6 percent federal matching rate increase for community-based attendant supports and services for individuals who require an institutional level of care.

The new LTSS options in the ACA interact with each other in ways that hold promise for improving the overall HCBS system. For example, states can “stack” enhanced federal matching rates for services that qualify under BIP, CFC, and/or MFP to increase the provision of HCBS. In addition, Maryland utilized lessons learned from its MFP demonstration to apply for BIP. BIP improves upon current rebalancing initiatives, including creating a conflict-free case management system, establishing a no wrong door/single entry point system, and utilizing a statewide core standardized assessment. Maryland’s MFP demonstration helped finance the structural changes required through BIP. In order to do this, its MFP operational protocol was revised in January 2012 to explicitly define programs and activities that help Maryland develop a more balanced system of LTSS in home and community-based settings. Three states reported challenges with coordinating the administration of the ACA LTSS options with MFP, but the majority of states (24 of 27 responding) reported no coordination problems at the time of the survey. In addition, the work that CMS and the states are undertaking to develop and implement these new options will help to improve and standardize access to HCBS across programs and funding sources. For example, CMS will share finalized elements from the BIP universal assessment instrument with states as an example for their use in CFC and other HCBS programs that require functional needs assessments. Together these options have the potential to improve care coordination for populations with chronic and complex health care needs.

Delivering LTSS in a Managed Care Model

Twenty-four MFP states reported operating or plans to implement a managed LTSS (MLTSS) program that will include MFP participants. These initiatives include enrollment of new eligibility groups into Medicaid managed care and new or expanded use of MLTSS. Tennessee has been operating its MLTSS programs (CHOICES) since 2010 and simultaneously enrolls beneficiaries into MFP and CHOICES. (For more information about Tennessee’s MFP Program, please see the companion case study.) An incentive structure allows MCOs to earn additional payments when an eligible person transitions into MFP, and again when the person has successfully resided in the community for a year. Additional payments are also tied to helping Tennessee achieve other MFP program benchmarks, including rebalancing LTSS expenditures, expanding participation in self-direction, and increasing the availability of contracted community-based residential alternative services for certain CHOICES participants. In the spring of 2014, Ohio will begin beneficiary enrollment in a three-year financial alignment demonstration for dually eligible beneficiaries. Under this initiative, managed care plans will be required to provide Medicare and Medicaid-covered services, as well as additional services under a capitated model of financing.12 Along with the demonstration, a Section 1915(b)/(c) waiver will combine all services contained in the state’s current HCBS waivers requiring a NF level of care into a single waiver. Ohio projects that approximately 41 percent of persons enrolled in Ohio’s MFP program may be eligible for the new waiver.

Only two states reported challenges coordinating a MLTSS program with MFP. One state reported challenges related to on-going training to ensure that MCOs are knowledgeable about the additional quality requirements required under MFP. Additionally, modifying IT and claims systems to ensure the states receive the MFP enhanced matching rate for services for beneficiaries enrolled in managed care was a reported challenge. Another state reported challenges getting the MCOs to understand transition services. Of the 24 states with MLTSS programs or plans to pursue MLTSS, 14 states reported no problems coordinating MLTSS programs with MFP; two states reported coordination challenges; and the remaining states either did not answer the survey question or were still in the process of developing their MLTSS programs. Since some MCOs may lack experience serving populations with complex needs, important consideration should be given to ensure adequate access to services.

Continuing Rebalancing Efforts Post-MFP

States will continue their commitment to rebalancing LTSS when MFP expires. We asked states to report their plans to continue transitioning Medicaid beneficiaries from institutions to the community if MFP is not reauthorized after 2016 (with funding currently available until 2020). Some states reported that they would request an extension of the MFP demonstration. Other states noted they are beginning to strategize and looking at developing, and then further ahead implementing, sustainable policies and procedures that continue transition efforts. By reviewing what has been accomplished and learned through the MFP program, states can synergize effective program features with the newer LTSS initiatives, such as BIP. States reported plans to continue transitioning individuals through a number of options including: transition programs that existed before MFP began, transitions under existing HCBS waivers, and transitions through MLTSS that may include financial incentives for MCOs to provide community-based services. For veteran MFP states, MFP was and continues to be the catalyst for larger LTSS system reforms with many of the MFP demonstration services and processes now operational in other Medicaid LTSS programs (e.g., HCBS waivers). For states newer to MFP, the demonstration is needed to support transition efforts and future rebalancing initiatives. This, along with other system changes such as the strengthening of the ADRC network and progress toward a no wrong door/single entry point system, will enhance access to HCBS.