Medicaid Section 1115 Managed Long-Term Services and Supports Waivers: A Survey of Enrollment, Spending, and Program Policies

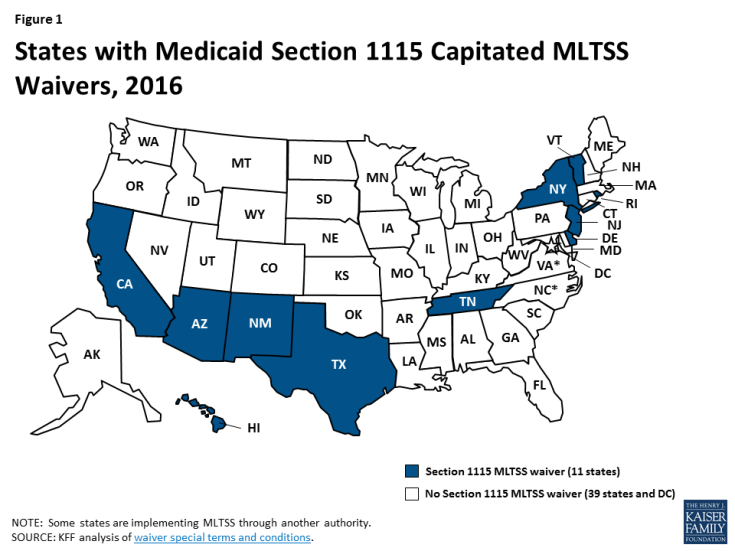

Medicaid fills a gap by covering long-term services and supports that are largely unavailable through private insurance or Medicare. These services play an important role in helping seniors and people with a variety of physical, cognitive, and behavioral health disabilities meet their daily self-care and household activity needs. While these services traditionally have been financed on a fee-for-service basis, more states are adopting capitated Medicaid managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) programs. Currently, 11 states are using § 1115 waivers to provide capitated MLTSS (Figure 1), with most of these waivers first approved in the last five years. Although the Medicaid program may change under the Trump Administration and new Congress, state delivery system choices in favor of MLTSS are likely to remain. This report presents findings from a Kaiser Family Foundation survey about § 1115 MLTSS waiver enrollment, spending, and program policies in 2015.

Key Findings

States are using § 1115 MLTSS waivers in efforts to streamline program administration, improve care coordination, and expand beneficiary access to home and community-based services (HCBS). These waivers authorize HCBS for multiple populations under a single authority and often include other Medicaid initiatives unrelated to MLTSS. Less than half of states with § 1115 MLTSS waivers cited the expectation that costs would be predictable as prompting their decision to pursue a waiver.

Most § 1115 MLTSS waivers include provisions designed to expand HCBS financial eligibility. Seven of 11 states equalize income limits for HCBS and institutional care, two states offer higher asset limits for HCBS than institutional care, and one state simplifies the application process to expedite access to HCBS.

Over half (6 of 11) of states with § 1115 MLTSS waivers expand HCBS eligibility to people with functional needs who are “at risk” of institutionalization. These initiatives seek to maintain beneficiaries in their homes and prevent the need for costlier, more intensive future services.

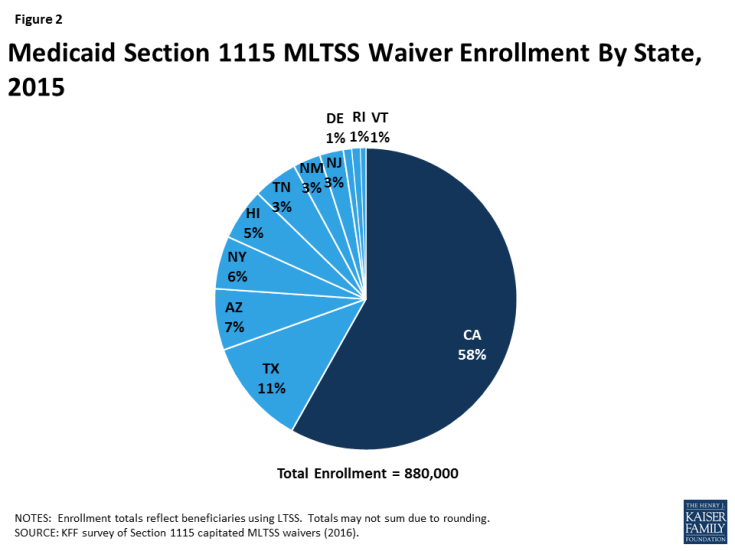

Nearly 900,000 beneficiaries were enrolled in the 11 states with § 1115 MLTSS waivers in 2015 (Figure 2). All 11 states enrolled seniors and people with physical disabilities. Three states enrolled people with intellectual or developmental disabilities in MLTSS in 2015, and two more states did so in 2016. All except one of the 11 states using § 1115 MLTSS waivers in 2015 require beneficiaries to enroll.

Four insurers offered health plans in more than one § 1115 MLTSS waiver state in 2015. United Healthcare had the highest market penetration, with contracts in eight of the 10 § 1115 waiver states that use private insurers to deliver MLTSS. Amerigroup and Molina each had contracts in three states, and Centene had contracts in two states.

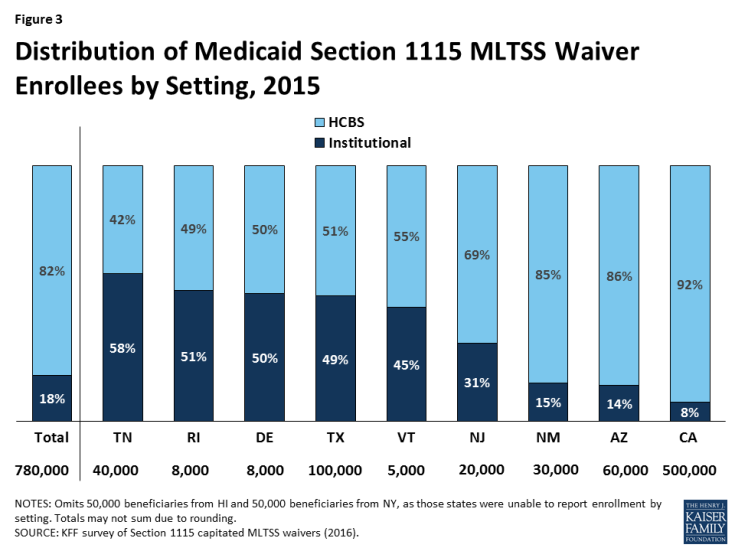

The vast majority of § 1115 MLTSS waiver beneficiaries were served in the community in the 9 states reporting 2015 enrollment by setting (Figure 3). However, there is variation in the HCBS vs. institutional split among states. Only 3 of 11 § 1115 MLTSS waiver states reported an HCBS waiting list in 2015.

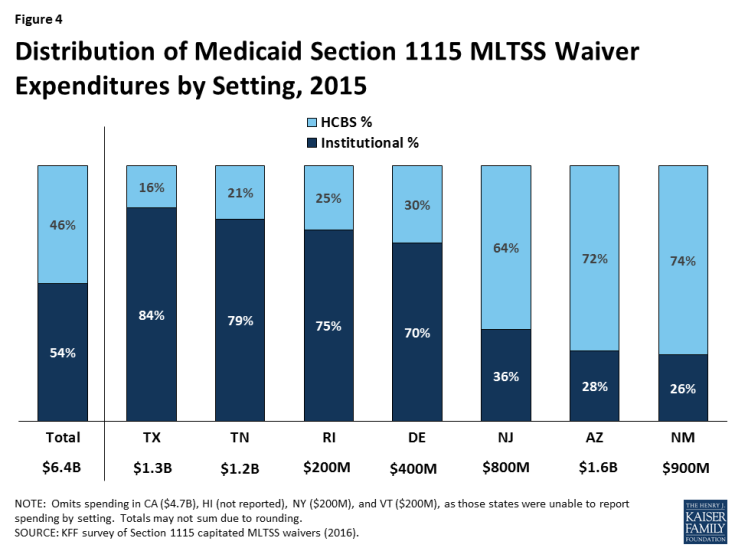

Just under half (46%) of § 1115 MLTSS waiver funds went to HCBS as opposed to institutional care in the 7 states reporting 2015 spending by setting (Figure 4). As with enrollment, there is variation in the community vs. institutional spending split among states. Section 1115 MLTSS waiver spending in 2015 totaled $11.4 billion across 10 states, with average spending per participant nearly three times higher for those receiving institutional services ($5,745 per month) than for those receiving HCBS ($1,949 per month) in the 6 states reporting that data. Most states offer financial incentives to encourage health plans to use HCBS as an alternative to institutional services.

Nearly all § 1115 MLTSS waiver states require their health plans to cover a comprehensive set of benefits including nursing facilities, HCBS, acute and primary care, and behavioral health services. All states provide the option to self-direct services, although the number of beneficiaries who do so is small and varies by state. Six states applied a maximum cost for HCBS per beneficiary, and 2 applied a maximum number of hours. Nearly all states incorporate nursing facility transition and/or diversion programs.

Conclusion

Capitated § 1115 MLTSS waivers contain a number of provisions designed to increase beneficiary access to HCBS. Some of these initiatives require waiver authority, while others can be implemented without waiver authority. States are setting financial eligibility limits to eliminate bias for institutional care over HCBS when individuals apply for Medicaid services. They also are expanding Medicaid HCBS eligibility by offering services to people who are at risk of institutionalization in efforts to prevent the need for costlier and more intensive services in the future. Within the context of capitated managed care financing, states are offering financial incentives to health plans that increase HCBS enrollment and spending. States also are including a comprehensive benefit package, with both institutional and HCBS, in their MLTSS programs to help avoid disincentives for HCBS. Other MLTSS benefit package elements that support community integration and beneficiary access to HCBS include self-direction and nursing facility diversion and/or transition programs. Finally, states are increasingly adopting quality measures related to LTSS rebalancing and quality of life and providing opportunities for stakeholder input into the design and oversight of MLTSS programs.

At the time of our survey, states were focused on implementing recent federal regulations, such as the MLTSS provisions in the 2016 Medicaid managed care rule and the home and community-based settings rule. Several states expressed concern about their ability to keep pace with the increasing need for LTSS given the growing number of seniors and people with disabilities and the LTSS workforce shortage. Although it is unclear how the Medicaid program may change under the Trump Administration and new Congress, state delivery system choices in favor of MLTSS are likely to remain, and the need for LTSS will only continue with the aging of the population. Given the continued state interest in capitated MLTSS programs and Medicaid’s central role in meeting the long-term care needs of seniors and people with disabilities, lessons from states’ experience with § 1115 MLTSS waivers may inform policymakers who are considering implementing or changing these programs.