Medicaid Section 1115 Managed Long-Term Services and Supports Waivers: A Survey of Enrollment, Spending, and Program Policies

Introduction

Medicaid fills a gap by covering long-term services and supports (LTSS) that are largely unavailable through private insurance or Medicare.1 These services play an important role in helping seniors and people with a variety of physical, cognitive, and behavioral health disabilities meet their daily self-care and household activity needs. LTSS include institutional care, such as nursing facility services, and home and community-based services (HCBS), such as personal care services, adult day health care programs, habilitative services, assistive technology, and case management.

Traditionally, LTSS have been financed on a fee-for-service basis. However, in recent years, state interest in capitated Medicaid managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) programs has increased. In these programs, states contract with private health plans to provide Medicaid-covered services for a per member per month rate.2 As more states implement MLTSS programs, spending on MLTSS as a percentage of all Medicaid LTSS spending has grown, increasing from 5% in FY 2009 to 15% in FY 2014.3 Acknowledging these trends, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for the first time included provisions governing MLTSS in its 2016 revision of the Medicaid managed care regulations.4 Although the Medicaid program may change under the Trump Administration and new Congress,5 state delivery system choices in favor of MLTSS are likely to remain.

MLTSS delivery systems seek to better coordinate and integrate LTSS with physical, behavioral health, and other services for seniors and people with disabilities who have some of the most intensive and chronic care needs. At the same time, MLTSS implementation comes with the potential risk of disrupting long-standing care arrangements on which beneficiaries rely for their most basic daily activities.6 Additionally, the delivery of LTSS involves concepts, such as person-centered planning, self-direction, and independent living, that health plans may not have encountered if their previous enrollment has been limited to relatively healthy populations, such as parents and children without disabilities.7

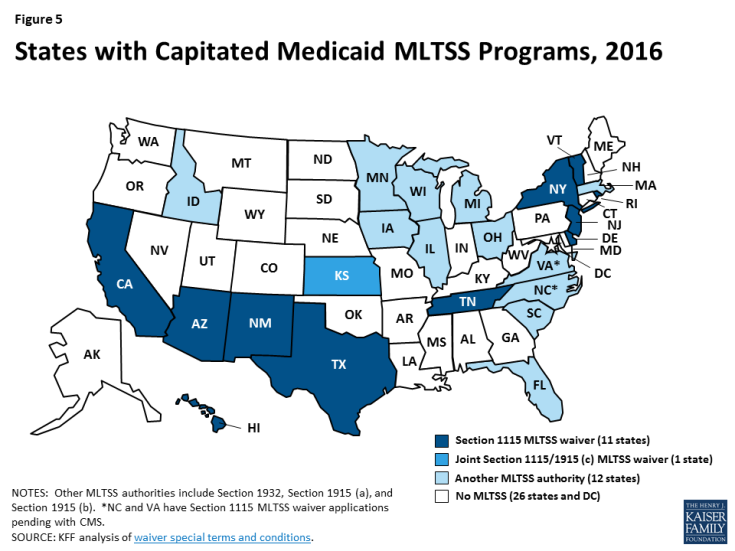

As of 2106, nearly half of states deliver Medicaid LTSS through capitated managed care for at least some populations (Figure 5).8 States can use various Medicaid authorities to implement capitated MLTSS programs. Eleven states presently are using § 1115 waivers, with most of these waivers first approved in the last five years (Appendix Table 1).9 Traditionally, states have used § 1915 (c) waivers to offer home and community-based services (HCBS) to seniors and people with disabilities who need LTSS and would otherwise be institutionalized;10 these services historically have been fee-for-service. Three states (AZ, RI, & VT) deliver all Medicaid HCBS through § 1115 capitated MLTSS waivers and do not administer any § 1915 (c) waivers. Another eight states (CA, DE, HI, NJ, NM, NY, TN, & TX) deliver Medicaid HCBS to some populations through § 1115 capitated MLTSS waivers and also administer at least one § 1915 (c) waiver to provide HCBS to other populations outside of managed care.

For the last 15 years, the Kaiser Family Foundation has surveyed states about enrollment, spending, and program policies in § 1915 (c) HCBS waivers.11 As more § 1915 (c) waivers are replaced by § 1115 MLTSS waivers, in 2016, we surveyed the 11 states using § 1115 capitated MLTSS waivers.12 This report presents our survey findings about MLTSS waiver enrollment, spending, and program policies in these states as of 2015, supplemented by our review of the waiver terms and conditions and other publicly available reports.13 Tables comparing key elements of these waivers are in the Appendix.

Key Findings

State Motivation to Implement § 1115 MLTSS Waivers

States use § 1115 waivers to authorize both Medicaid managed care and HCBS. States generally need waiver authority to require beneficiaries to enroll in MLTSS, which is available under § 1115 or § 1915 (b). Because § 1915 (b) is limited to Medicaid managed care and cannot be used to authorize HCBS, states with § 1915 (b) MLTSS waivers also operate § 1915 (c) waivers that authorize HCBS.14 By contrast, nearly all states with § 1115 MLTSS waivers use § 1115 to authorize both managed care and HCBS.15

States with § 1115 MLTSS waivers provide HCBS to multiple populations under a single authority. Section 1915 (c) HCBS waivers can be targeted to a particular population, such as seniors, people with physical disabilities, or people with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD). Under § 1115, states can consolidate multiple § 1915 (c) waivers into one authority to streamline reporting and oversight while continuing to offer the same services to the same populations.16 For example, New Jersey’s § 1115 MLTSS waiver includes populations previously served under four separate § 1915 (c) waivers: seniors and people with physical disabilities who otherwise would require nursing facility care, adults with physical disabilities who need assistance with three activities of daily living, adults with traumatic brain injuries, and adults with AIDS.

States use § 1115 waivers to implement other Medicaid initiatives in addition to MLTSS. Unlike § 1915 (b) waivers, which are limited to managed care, § 1115 waivers can authorize other programs, such as delivery system reform incentive payments, that may not be directly related to capitated MLTSS. For example, New Mexico’s § 1115 waiver allows it to administer a capitated managed care program for beneficiaries without LTSS needs, a healthy behavior rewards program, and a safety net care pool, in addition to MLTSS. Some states, such as New Mexico and Texas, originally implemented MLTSS through joint § 1915 (b)/(c) waivers and later transitioned their MLTSS programs to a § 1115 waiver to consolidate various Medicaid program elements under a single authority.

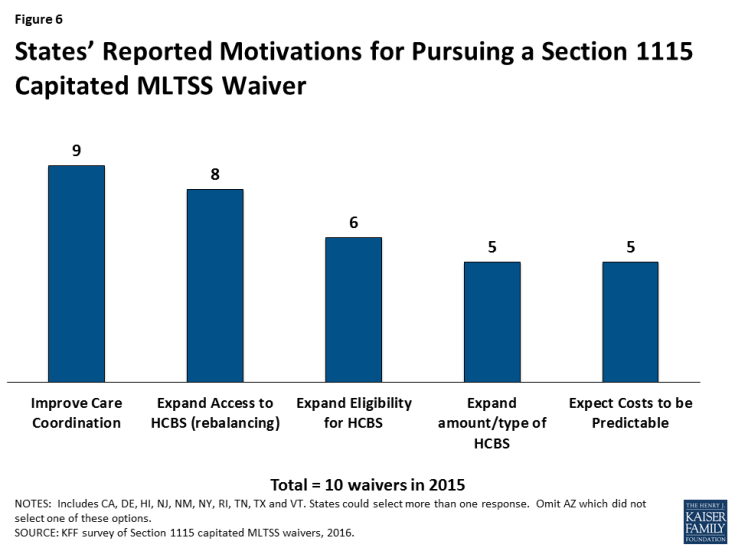

Most states report that their decision to implement a § 1115 capitated MLTSS waiver is motivated by a desire to improve care coordination and expand access to HCBS as an alternative to institutional care (Figure 6).17 Less than half of states with § 1115 MLTSS waivers cited the expectation that costs would be predictable as prompting their decision to pursue a capitated MLTSS waiver. Other less frequently cited reasons for pursing § 1115 MLTSS waivers included expanding eligibility for HCBS and expanding the amount or type of services offered.

Financial Eligibility in § 1115 MLTSS Waivers

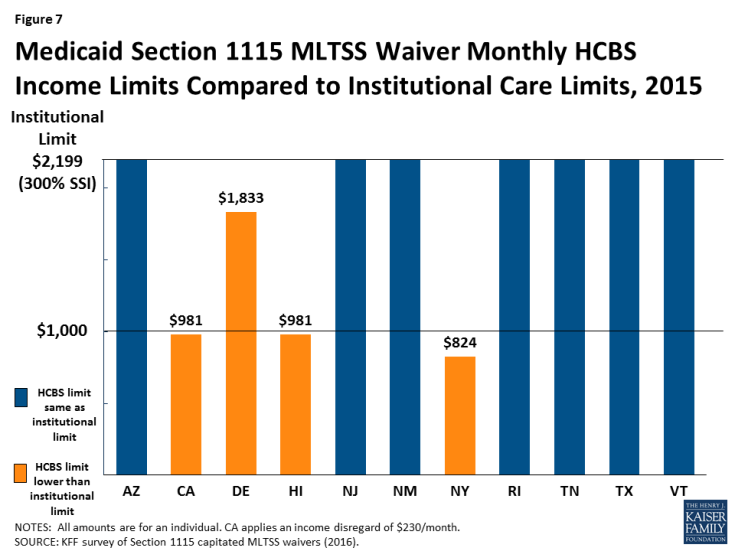

Most (7 of 11) states with § 1115 MLTSS waivers use the same income limit for HCBS and institutional services (Figure 7). The federal maximum income for Medicaid LTSS is 300% of the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefit, or $2,199 per month for an individual in 2015. All 11 § 1115 MLTSS waiver states adopt the federal maximum for institutional care.18 Establishing the same income limit for HCBS removes any potential bias toward institutional care, which may occur if people who need LTSS can receive institutional care at higher incomes than the limit for HCBS. Four states (CA, DE, HI, & NY) have HCBS income limits that are more restrictive than 300% of SSI. Delaware sets the maximum income for HCBS at 250% of SSI, or $1,833 per month for an individual in 2015. California and Hawaii use 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL), or $981 per month for an individual in 2015, with California also applying a $230 per month income disregard. New York’s HCBS income limit is 84% FPL, or $824 per month for an individual in 2015.19

Figure 7: Medicaid Section 1115 MLTSS Waiver Monthly HCBS Income Limits Compared to Institutional Care Limits, 2015

Two states (RI & VT) use a higher asset limit for HCBS than for institutional care. The other nine § 1115 MLTSS waiver states apply the SSI asset limit of $2,000 for an individual to both HCBS and institutional care.20 Authorizing a higher asset limit for HCBS recognizes that people who live in the community may incur additional expenses to maintain their housing. Rhode Island sets its HCBS asset limit at $4,000 per individual.21 Vermont uses a $10,000 per individual limit for people who own and reside in their own homes, receive HCBS and would otherwise require institutionalization. Additionally, New Jersey’s waiver eliminates the five-year asset transfer look-back period for LTSS applicants with income at or below 100% FPL.

Rhode Island’s waiver includes a provision that offers faster access to HCBS by allowing applicants to self-attest to financial eligibility. In general, states have up to 90 days to determine Medicaid LTSS eligibility. The delay can make it difficult for people who need services to remain in the community and lead them to enter a nursing facility that agrees to provide care pending their Medicaid eligibility determination. Returning to the community becomes more difficult once a person enters a nursing facility and loses their community housing and other supports. To address this issue, Rhode Island allows new Medicaid applicants who are functionally eligible for LTSS to self-attest to financial eligibility and receive a limited benefit package of HCBS for three months while their full financial eligibility determination is pending. Benefits include up to 20 hours per week of personal care and homemaker services, three days per week of adult day care services, and limited skilled nursing facility services.

Functional Eligibility in § 1115 MLTSS Waivers

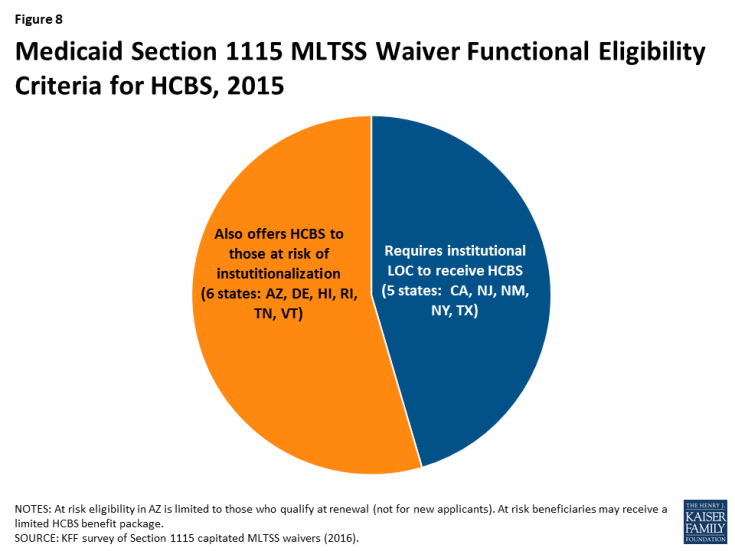

More than half (6 of 11) of § 1115 MLTSS waiver states extend HCBS eligibility to people with functional needs that do not yet rise to an institutional level of care (Figure 8).22 These beneficiaries are considered “at risk” of future institutionalization. States provide HCBS to at risk populations in an effort to maintain beneficiaries in their homes and prevent their needs from deteriorating to the point where they would require costlier and more intensive services in the future. HCBS eligibility for at risk beneficiaries in Arizona is limited to non-elderly adults who qualify based on mental illness or I/DD at renewal. The other five states allow new Medicaid applicants who are at risk of institutionalization to receive HCBS as follows:

- Delaware offers HCBS to at risk adults and children with disabilities up to 250% FPL.23 Both the financial eligibility criteria and the benefit package are the same as for beneficiaries who already meet an institutional level of care.

- Hawaii offers a limited HCBS benefit package to at risk beneficiaries. Benefits include adult day care, adult day health, home delivered meals, personal assistance, personal emergency response systems, and skilled nursing services.

- Rhode Island offers a limited HCBS benefit package to at risk seniors and adults with dementia up to 250% FPL and adults with disabilities up to 300% SSI. Benefits include homemaker, personal care, and respite services; minor environmental modifications; and physical therapy evaluation and services.

- Tennessee offers HCBS capped at $15,000 per year24 to at risk seniors and non-elderly people with disabilities who qualify as SSI beneficiaries.25 Additionally, Tennessee began offering services to at risk adults and children with I/DD, in 2016. Adults with I/DD have a soft cap of $30,000 per year, which can be increased by an additional $6,000 in emergencies. These adults instead may choose to receive services capped at $15,000 per year but with the option to pay family caregivers. Services for all at risk children with I/DD are capped at $15,000 per year with the option to pay family caregivers.

- Vermont offers a limited HCBS benefit package to at risk beneficiaries using the same financial eligibility criteria as for those who meet an institutional level of care (300% SSI). Benefits include adult day, case management, and homemaker services.

Rhode Island’s waiver also expands eligibility for HCBS by covering young adults ages 19 to 21 with significant disabilities and income below 250% FPL who have aged out of the Katie Beckett coverage group, need medical, behavioral health, or DD services, and are otherwise ineligible for Medicaid.26 The Katie Beckett pathway covers children up to age 19 with significant disabilities receiving HCBS who would otherwise be institutionalized.

Enrollment in § 1115 MLTSS Waivers

Total Enrollment

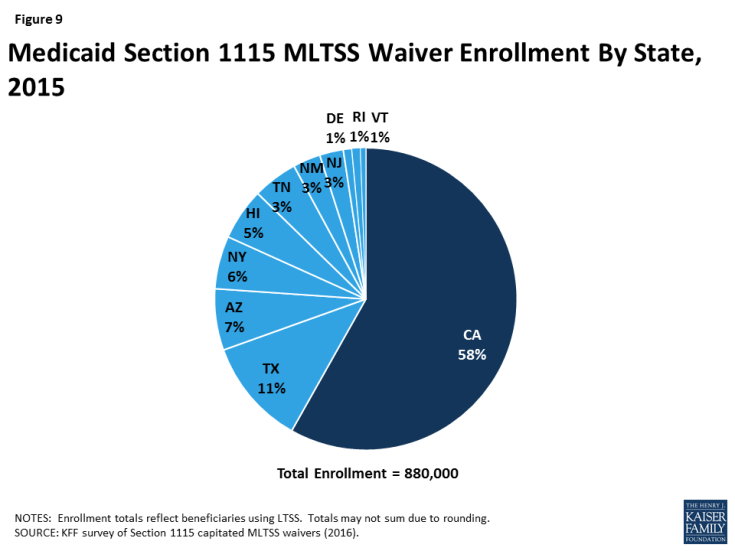

Nearly 900,000 beneficiaries in 11 states were enrolled in a § 1115 waiver for MLTSS in 2015 (Figure 9).27 Enrollment varied widely across the states. California had the largest number of people receiving MLTSS under its waiver, with 500,000 enrollees. The state with the next highest enrollment was Texas, with 100,000 enrollees receiving MLTSS. The state with the smallest number of MLTSS enrollees was Vermont, with 5,000 beneficiaries. Nearly all § 1115 MLTSS waiver states enroll beneficiaries statewide; the exception is California, where enrollment is limited to certain counties.

Enrollment by Population

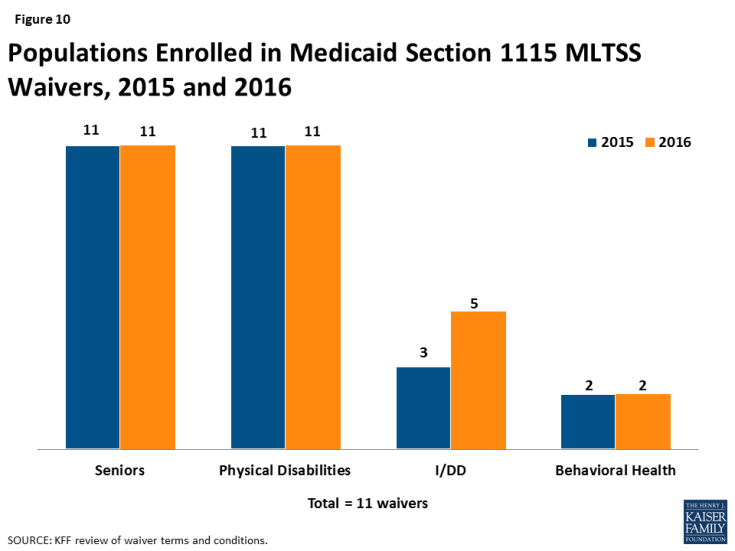

All states enrolled seniors and non-elderly adults with physical disabilities in their § 1115 MLTSS waivers in 2015 (Figure 10). Three states (AZ, RI, & VT) enrolled people with I/DD in MLTSS, although Arizona and Vermont both use a state entity instead of private health plans to provide services to this population. Two states (NY & VT) enrolled adults with behavioral health needs.

The number of states enrolling people with I/DD in § 1115 MLTSS waivers is growing (Figure 10). In addition to the three states (AZ, RI, & VT) enrolling this population in 2015, two more states (NY & TN) began enrolling beneficiaries with I/DD in MLTSS in 2016.28 Five other states (DE, HI, NJ, NM, & TX) enroll people with I/DD in managed care under their waivers for acute care but not for LTSS.

All 11 states with § 1115 MLTSS waivers include beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. These beneficiaries receive their Medicaid benefits through MLTSS. Seven states (AZ, CA, DE, NJ, RI, TN, & TX) require their MLTSS health plans to coordinate with Medicare-covered services for dual eligible beneficiaries. For example, Tennessee requires its MLTSS health plans to set up companion Medicare D-SNPs to allow dual eligible beneficiaries to receive both Medicare and Medicaid services from the same entity. Four states (CA, NY, RI & TX) have concurrent § 1115A authority for financial alignment demonstrations that integrate Medicare and Medicaid benefits for dual eligible beneficiaries in a single health plan.29

Enrollment by Setting

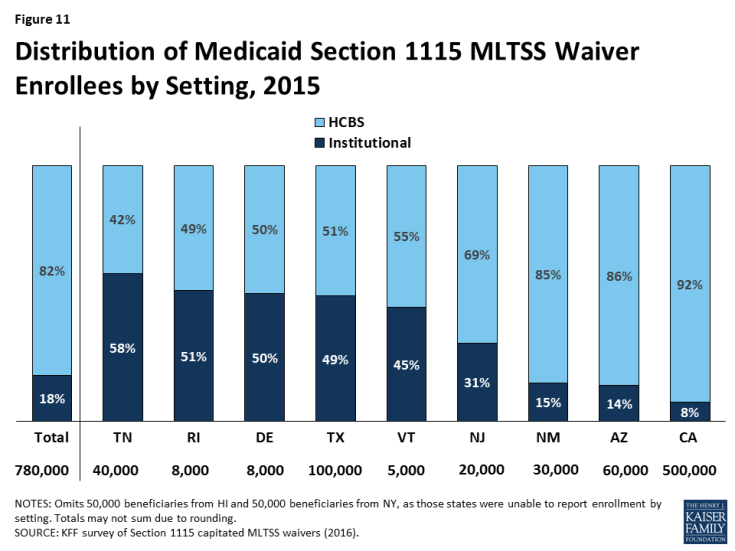

Over 80% of § 1115 MLTSS waiver enrollees received services in the community instead of institutions, across the 9 states that reported 2015 enrollment by setting (Figure 11). Only one state reporting this data (TN) served a clear majority of MLTSS beneficiaries (58%) in institutions in 2015. However, Tennessee has made substantial progress in increasing the number of beneficiaries receiving HCBS, as 83% of its LTSS beneficiaries were served in institutions in 2010.30 Additionally, Tennessee reports that more than half of its new LTSS beneficiaries selected HCBS upon enrollment in each of the past two years.31 Four states (DE, RI, TX, & VT) had about a 50/50 split between beneficiaries in the community versus institutions. The other four states (NJ, NM, AZ & CA) served a majority of beneficiaries in the community. Hawaii and New York did not report enrollment by setting, but Hawaii’s reports to CMS indicate that nearly 2/3 of its MLTSS enrollees received HCBS in the quarter ending March 2015.32

HCBS Waiting Lists

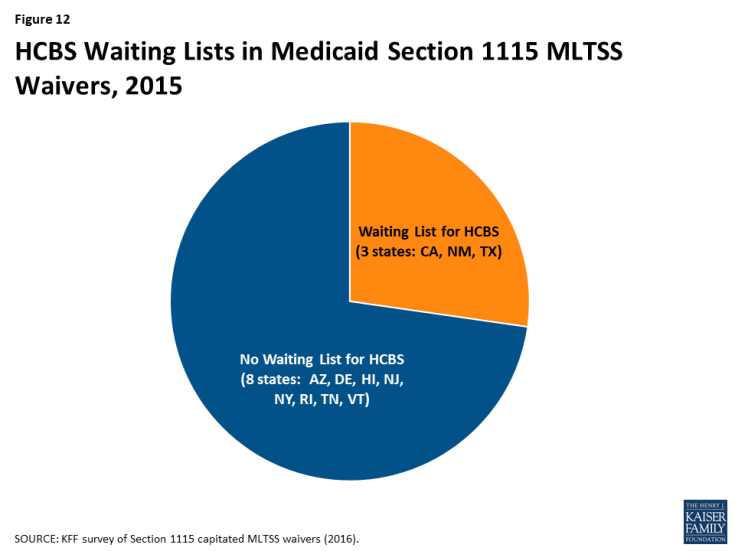

Nearly three-quarters (8 of 11) of § 1115 MLTSS waiver states did not have an HCBS waiting list in 2015 (Figure 12). States can cap HCBS enrollment under § 1115 MLTSS waivers just as they can under § 1915 (c) waivers.33 Three § 1115 MLTSS waiver states (CA, NM, & TX) reported an HCBS waiting list in 2015. New Mexico had 16,370 people waiting, with a four-month average wait time before receiving services. Nearly 1,700 people on the waiting list were offered services in New Mexico in 2015. Texas had 15,712 people waiting, with a six month average wait time.34 Over 1,800 people on the waiting list were offered services in Texas between September, 2015 and March, 2016. California was unable to report waiting list data.

MLTSS Health Plans

Four insurers offered health plans in more than one § 1115 MLTSS waiver state in 2015 (Table 1). United Healthcare had the highest market penetration, with contracts in eight of the 10 § 1115 waiver states that use private insurers to deliver MLTSS.35 Amerigroup and Molina each had contracts in three states, and Centene had contracts in two states. States contract with a range of insurer types, including primarily small local insurers (CA), large national insurers (TX, NM, & NJ), or a mix of both (AZ, TN, & NY).

| Table 1: Health Plans Participating in Multiple § 1115 MLTSS Waiver States, 2015 | ||||

| State | United Healthcare | Amerigroup | Molina | Centene |

| Arizona | X | X | ||

| California | X | |||

| Delaware | X | |||

| Hawaii | X | |||

| New Jersey | X | X | ||

| New Mexico | X | X | ||

| New York | X | |||

| Rhode Island | ||||

| Tennessee | X | X | ||

| Texas | X | X | X | X |

| TOTAL: | 8 states | 3 states | 3 states | 2 states |

| NOTES: Omits Vermont, which uses a state entity to deliver MLTSS. SOURCE: KFF survey of § 1115 Medicaid MLTSS waivers (2016). |

||||

Enrollment Policies

Nearly all § 1115 MLTSS waiver states (except RI) require beneficiaries to enroll in managed care. Enrollment in specialized health plans for beneficiaries with behavioral health needs is voluntary in New York.36 States typically use passive enrollment processes in which beneficiaries are automatically assigned to a health plan if they do not affirmatively select one. For example, if a beneficiary does not choose a health plan within a certain amount of time, such as 30 days, of their Medicaid eligibility determination, the state or its enrollment broker will select a health plan for them, and beneficiaries then have a period of time, such as 90 days, to change health plans.

Nearly all § 1115 MLTSS waiver states (except AZ) offer independent enrollment options counseling to assist beneficiaries with choosing a health plan. States use different types of entities to provide this service, with about half of states using an enrollment broker, and others relying on local Aging and Disability Resource Centers (ADRCs) or ombudsman programs (Table 2). Options counseling seeks to help LTSS enrollees select a health plan; this population may not be familiar with that process because they traditionally have been enrolled in the fee-for-service delivery system. LTSS enrollees also may seek assistance with choosing a health plan to find a provider network that best meets their various needs – which may go beyond primary care to include specialists, behavioral health providers, durable medical equipment suppliers, and personal care attendants — and preserves their existing provider relationships to the extent possible. CMS’s 2016 Medicaid managed care regulations require all states to offer enrollee choice counseling through the independent beneficiary support system required in health plan contracts beginning on or after July 1, 2018.37

| Table 2: Type of Entity Providing Independent Enrollment Options Counseling in § 1115 MLTSS Waiver States, 2015 | ||||

| State | Enrollment Broker | Aging & Disability Resource Center | Ombudsman | No Enrollment Counseling |

| Arizona | X | |||

| California | X | |||

| Delaware | X | |||

| Hawaii | X | |||

| New Jersey | X | X | ||

| New Mexico | X | |||

| New York | X | X | ||

| Rhode Island | X | |||

| Tennessee | X | |||

| Texas | X | X | ||

| TOTAL: | 6 states | 3 states | 3 states | 1 state |

| NOTE: Omits VT which does not use health plans because a state entity delivers services. SOURCE: KFF survey of § 1115 Medicaid MLTSS waivers (2016). |

||||

Disenrollment Policies

Over three-quarters (7 of 9) of the § 1115 MLTSS waiver states with mandatory health plan enrollment allow beneficiaries to switch health plans outside of the annual open enrollment period if their LTSS provider leaves the plan’s network. These states include CA, DE, HI, NJ, NM, NY, and TX.38 The two other states with mandatory MLTSS health plan enrollment (TN & AZ) permit beneficiaries to change plans based on circumstances that would create a hardship as defined by the state or when the change helps to ensure continuity of care. CMS’s 2016 Medicaid managed care rule requires states to allow beneficiaries to disenroll from their health plan outside of open enrollment if their residence or employment would be disrupted as a result of their residential or employment supports provider leaving their plan’s network in health plan contracts beginning on or after July 1, 2017.39

Spending in § 1115 MLTSS Waivers

Ten § 1115 waiver states reported total MLTSS spending of $11.4 billion in 2015.40 These states include AZ, CA, DE, NJ, NM, NY, RI, TN, TX, and VT. Hawaii did not report spending data.

Spending by Setting

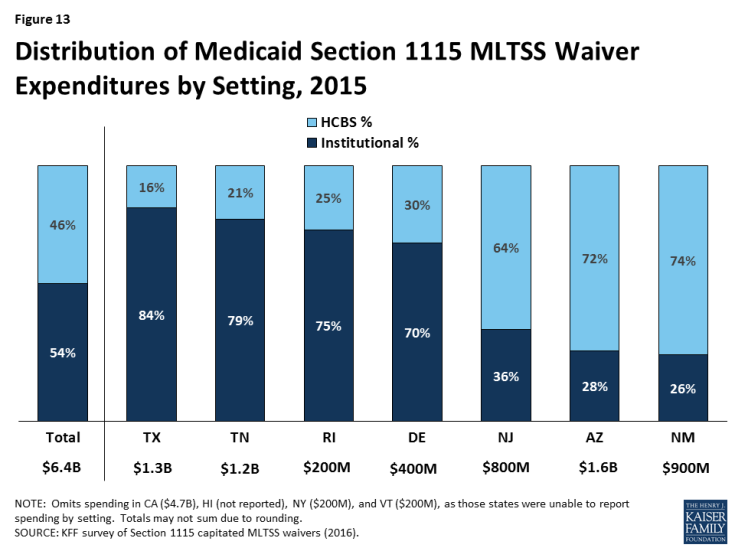

Just under half (46%) of § 1115 MLTSS waiver spending went to HCBS in 2015, across the seven states that were able to break out spending by setting (Figure 13). The split between HCBS and institutional spending varied by state. Three states (AZ, NJ, & NM) spent over 60% of their MLTSS dollars on HCBS, while four states (DE, RI, TN, & TX) spent 70% or more of their MLTSS dollars on institutional services.

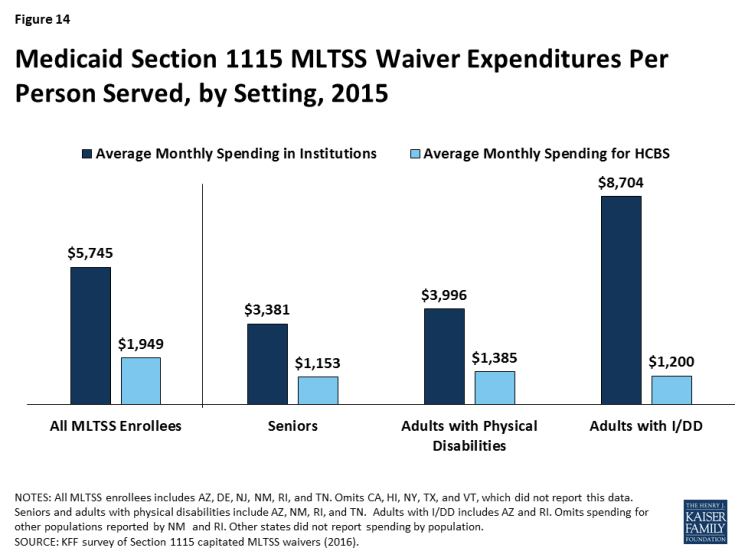

Average spending per participant receiving institutional services ($5,745 per month) was nearly three times higher than average spending per participant receiving HCBS ($1,949 per month) in the six § 1115 MLTSS waiver states reporting this data for 2015 (Figure 14). The states include AZ, DE, NJ, NM, RI, and TN. This disparity also is evident when comparing per participant spending for institutional services versus HCBS by population. States spent nearly three times the amount per participant on institutional care for both seniors and adults with physical disabilities than for their counterparts living in the community in the four states (AZ, NM, RI, & TN) reporting this data by population and setting (Figure 14 ).41 Spending on services for adults with I/DD in institutions cost nearly seven times more than for their counterparts who were served in the community in the two states (AZ & RI) reporting this data. Part of the reason that institutional spending exceeds the cost of HCBS is that Medicaid does not pay for community-based housing, whereas institutional services necessarily come with room and board.42

Health Plan Financial Incentives for Increased HCBS Utilization

Most § 1115 MLTSS waiver states build financial incentives into their capitated rates to encourage health plans to use HCBS as an alternative to institutional services. These arrangements typically involve a blended rate that pays the same amount regardless of whether a beneficiary receives nursing facility services or HCBS. Because HCBS usually are less expensive than institutional care, higher HCBS utilization increases health plans’ operating margins under a blended rate. For example, California’s blended rate for MLTSS beneficiaries under its waiver assumes a certain proportion of enrollees in institutions versus in the community. If health plans actually serve more enrollees in the community, they are still paid at the rate based on the lower assumption. This rate structure disincentivizes health plans from shifting enrollment from HCBS to institutional services.

Some § 1115 MLTSS waiver states offer bonus payments to health plans that increase HCBS utilization. New Jersey’s nursing facility transition incentive payment program provides financial bonuses to health plans that successfully transition beneficiaries from nursing facilities to the community for 120 days. Tennessee offers incentive payments to health plans that achieve specified benchmarks, such as the number of enrollees who receive HCBS and the proportion of LTSS spending on HCBS vs. institutional care. Hawaii’s waiver allows the state to offer financial incentives to health plans that expand HCBS capacity beyond annual state-established thresholds and penalties for plans that fail to do so at a state-determined appropriate pace. Hawaii health plans receiving these financial incentives must share a portion with providers but cannot pass penalties on to providers.

Services in § 1115 MLTSS Waivers

Benefit Packages

Most § 1115 MLTSS waiver states require their health plans to cover a comprehensive set of benefits including nursing facilities, HCBS, acute and primary care, and behavioral health services. An exception is New York, where health plans provide limited Medicaid state plan benefits, including LTSS, with the remaining services provided fee-for-service. The MLTSS health plan benefit package in New York includes home health, medical social, adult day health, personal care, durable medical equipment, non-emergency medical transportation, podiatry, dental, optometry, outpatient rehabilitation, audiology, respiratory therapy, private duty nursing, nutrition, skilled nursing facility, social day care, home delivered meals, social and environmental supports, and personal emergency response system services.43 Additionally, two states (DE & HI) limit the number or type of behavioral health visits in the health plan benefit package, with more intensive services provided through a carve-out. Texas added nursing facility services to its MLTSS benefit package in March 2015; previously, those services were carved out. Including both institutional and HCBS in the health plan benefit package can incentivize the use of HCBS, which are typically less expensive than comparable institutional care.

Self-direction

All of the § 1115 MLTSS waiver states require their health plans to offer beneficiaries the option to self-direct HCBS, although the number of beneficiaries who do so is relatively small and varies by state. Self-direction can include the ability to allocate service budgets and/or select, train, and dismiss service providers. The median self-direction participation rate in 2015 was seven percent across all § 1115 MLTSS waiver states. Self-direction participation rates ranged from 100% in California, where all beneficiaries receiving in-home supportive services under the waiver direct their personal care and attendant services, to less than five percent in New Mexico, Rhode Island, and Texas.

Three § 1115 MLTSS waiver states have provisions that authorize payments to family caregivers. Arizona and Vermont allow spouses to be paid for providing personal care services (up to 40 hours per week in AZ). As of 2016, Tennessee’s waiver provides an option for a family caregiver stipend up to $500 for children and $1,000 for adults with I/DD who either meet or are at risk of meeting an institutional level of care, in lieu of receiving supportive home care services.

HCBS Utilization controls

Six of the § 1115 MLTSS waiver states applied a maximum HCBS cost per beneficiary (AZ, CA, NJ, NM, TN, & TX), and two applied a maximum number of hours (AZ & CA). States typically set the maximum HCBS cost at the same amount as the cost of nursing facility services or a percentage of the nursing facility cost. With its § 1115 MLTSS waiver expansion to people with I/DD in 2016, Tennessee offers up to $45,000 per year of services for adults with I/DD with low to moderate needs who meet an institutional level of care and up to $60,000 per year of services for adults with I/DD with high needs who meet an institutional level of care. These amounts can be exceeded up to the average cost of institutional services for people with intellectual disabilities and exceptional medical or behavioral needs. Three other states noted policies that provide exceptions to the maximum cost: Texas allows beneficiaries to exceed the maximum cost, which is set at 202% of the cost of nursing facility services, when general revenue funds are used to pay for services,44 New Mexico exempts beneficiaries who self-direct services from its cost cap, and Arizona allows the maximum cost to be exceeded based on a cost effectiveness study. Among states that apply maximum hour limits, Arizona applies service specific guidelines, and California limits in-home supportive services to 283 hours per month.

Nursing Facility Transition and Diversion Programs

Eight § 1115 MLTSS waiver states involve health plans in their Money Follows the Person (MFP) programs (CA, DE, HI, NJ, NM, RI, TN, & TX).45 Two states (AZ & NM) do not participate in MFP; Vermont participates in MFP but does not use private health plans in its capitated managed care model. The MFP demonstration provided states with enhanced federal Medicaid matching funds for 12 months for each Medicaid beneficiary who transitions from an institution to the community.46 Health plan involvement with MFP in § 1115 MLTSS waiver states includes coordinating transitions (8 states), providing services (8 states), and referring candidates for transition to the state (6 states).

Five § 1115 MLTSS waiver states require their health plans to have nursing facility diversion programs (AZ, HI, NJ, RI, & TN). For example, health plans providing services under New Jersey’s waiver must have a nursing facility diversion plan approved by the state and CMS for beneficiaries who receive HCBS and those at risk of NF placement, including short-term stays. Plans must monitor hospitalizations and short stay nursing facility services for at risk beneficiaries.

Quality Measures in § 1115 MLTSS Waivers

Nine of the 11 § 1115 MLTSS waiver states used quality measures to assess progress in LTSS rebalancing in 2015.47 These states include AZ, CA, HI, NJ, NM, RI, TN, TX and VT. In addition, New York noted that quality measures related to LTSS rebalancing are included in its § 1115A financial alignment demonstration for dual eligible beneficiaries, although not currently in its § 1115 MLTSS waiver. Examples of quality measures related to LTSS rebalancing are listed in Table 3.

| Table 3: Examples of Quality Measures Related to LTSS Rebalancing in § 1115 MLTSS Waiver States | |

| State | Selected Measures |

| Rhode Island |

|

| Tennessee |

|

| Texas |

|

| SOURCE: KFF survey of § 1115 Medicaid MLTSS waivers (2016) and review of waiver terms and conditions. | |

Seven states reported using measures that assess beneficiary quality of life in 2015. These states include AZ, NJ, NM, NY, RI, TN, and TX. Three of these states (NJ, TN, & TX) indicated that they participate in the National Association of States United for Aging and Disabilities’ National Core Indicators – Aging and Disability survey, which assesses quality of life and outcomes for seniors, people with physical disabilities, and caregivers.48 Examples of quality measures related to beneficiary quality of life are listed in Table 4. CMS’s 2016 Medicaid managed care rule requires states that provide MLTSS to identify standard performance measures related to quality of life, rebalancing, and community integration for health plan contracts starting on or after July 1, 2017.49

| Table 4: Examples of Quality Measures Related to Beneficiary Quality of Life in § 1115 MLTSS Waiver States | |

| State | Selected Measures |

| NCI Aging and Disability survey (used by NJ, TN, & TX) |

|

| Texas |

|

| NOTE: DE is listed as a NCI-AD participant at http://nci-ad.org/ but did not indicate this in its survey response. SOURCE: KFF survey of § 1115 Medicaid MLTSS waivers (2016); National Core Indicators – Aging and Disability Adult Consumer Survey 2015-2016 Mid-Year Results at 192, http://nci-ad.org/upload/reports/NCI-AD_2015-2016_Six_State_Mid-Year_Report_FINAL.pdf. |

|

Stakeholder Engagement and Oversight in § 1115 MLTSS Waivers

MLTSS Advisory Groups

Five of the 11 § 1115 MLTSS waiver states require health plans to have an advisory committee that includes beneficiaries receiving LTSS as of 2015. These states include AZ, NJ, NM, TN, and TX. Under the 2016 Medicaid managed care rule, MLTSS plans must have a member advisory committee that includes a reasonably representative sample of the populations receiving LTSS covered by the plan or other individuals representing those enrollees, effective for plan contracts starting on or after July 1, 2017.50

Five states must have a state advisory committee that allows stakeholders to provide input about MLTSS implementation according to their § 1115 waiver terms and conditions. These states include DE, NJ, NM, NY, and TX. The 2016 Medicaid managed care rule requires all states to have a stakeholder group to solicit and address the opinions of beneficiaries, individuals representing beneficiaries, providers, and other stakeholders in the design, implementation, and oversight of a state’s MLTSS program, effective for plan contracts beginning on or after July 1, 2017.51

Ombudsman programs

Eight of 11 § 1115 MLTSS waiver states operated an LTSS ombudsman program in 2015 (Table 5). Four of these states locate their ombudsman program entirely outside state government (HI, NY, TN, & VT), while three operate entirely within state government (CA, DE, & TX). New Mexico divides the functions of its ombudsman program among the state government long-term care ombudsman and community-based organizations, such as ADRCs, Area Agencies on Aging (AAA), and Centers for Independent Living. All ombudsman programs are independent of the MLTSS health plans. Ombudsman programs may provide enrollment options counseling, assist beneficiaries with health plan appeals, offer information about state fair hearings, track beneficiary complaints, train health plans and providers about community-based services and supports that can be linked with MLTSS-covered services, and report data and systemic issues to states. In addition, waivers in two states (NJ & RI) that do not provide for an ombudsman program instead require beneficiaries to have access to an independent advocate within the state, such as the state protection and advocacy agency for people with disabilities, a legal services agency, or AAA. The 2016 Medicaid managed care rule requires states to offer an independent beneficiary support system, in plan contracts beginning on or after July 1, 2018, that provides the following services for people who use or wish to use LTSS: (1) an access point for complaints and concerns; (2) education on enrollee rights and responsibilities; (3) assistance in navigating the grievance and appeals process; and (4) review and oversight of data to guide the state in identifying and resolving systemic LTSS issues.52

| Table 5: Type of Entity Providing Ombudsman Services in § 1115 MLTSS Waiver States, 2015 | ||||

| State | State Government | Outside of State Government | Functions Divided Among State Government and Outside Entities | No Program |

| Arizona | X | |||

| California | X | |||

| Delaware | X | |||

| Hawaii | X | |||

| New Jersey | X | |||

| New Mexico | X | |||

| New York | X | |||

| Rhode Island | X | |||

| Tennessee | X | |||

| Texas | X | |||

| Vermont | X | |||

| TOTAL: | 4 states | 3 states | 1 state | 3 states |

| NOTES: NJ and RI’s waivers do not provide for an ombudsman program but do require beneficiaries to have access to an independent advocate within the state. SOURCE: KFF survey of § 1115 Medicaid MLTSS waivers (2016). |

||||

Conclusion

As of 2015, 11 states are using § 1115 waivers to provide capitated MLTSS, and all except one require beneficiaries to enroll. Nearly 900,000 beneficiaries were enrolled in these programs. All states enrolled seniors and non-elderly people with physical disabilities. Three states enrolled people with I/DD in 2015, although the number of states enrolling this population increased to five states in 2016. The vast majority of MLTSS beneficiaries in the 9 states reporting 2015 enrollment by setting were served in the community, although there is variation in the community vs. institutional split among states. Only 3 of 11 § 1115 MLTSS waiver states reported an HCBS waiting list in 2015.

Section 1115 MLTSS waiver spending in 2015 totaled $11.4 billion across the 10 states reporting this data. Average spending per participant was nearly three times higher for those receiving institutional services ($5,745 per month) than for those receiving HCBS ($1,949 per month) in the six states reporting this data. Among the seven states reporting MLTSS spending by setting, just under half (46%) of § 1115 MLTSS waiver funds went to HCBS as opposed to institutional care, with variation in the community vs. institutional split among states.

States are using § 1115 waivers to implement capitated MLTSS programs in an effort to streamline administration. Section 1115 allows states to provide HCBS to multiple populations and implement other provisions, such as delivery system reforms unrelated to MLTSS, under a single authority. States also report adopting capitated MLTSS programs through § 1115 waivers in efforts to increase care coordination across physical, behavioral health, and LTSS.

Capitated § 1115 MLTSS waivers contain a number of provisions designed to increase beneficiary access to HCBS. Some of these initiatives require waiver authority, while others can be implemented without waiver authority. States are setting financial eligibility limits to eliminate bias for institutional care over HCBS when individuals apply for Medicaid services. They also are expanding Medicaid HCBS eligibility by offering services to people who are at risk of institutionalization in efforts to prevent the need for costlier and more intensive services in the future. Within the context of capitated managed care financing, states are offering financial incentives to health plans that increase HCBS enrollment and spending. States also are including a comprehensive benefit package, with both institutional and HCBS, in their MLTSS programs to help avoid disincentives for HCBS. Other MLTSS benefit package elements that support community integration and beneficiary access to HCBS include self-direction and nursing facility diversion and/or transition programs. Finally, states are increasingly adopting quality measures related to LTSS rebalancing and quality of life and providing opportunities for stakeholder input into the design and oversight of MLTSS programs.

At the time of our survey, states were focused on implementing recent federal regulations, such as the MLTSS provisions in the 2016 Medicaid managed care rule and the home and community-based settings rule. Several states expressed concern about their ability to keep pace with the increasing need for LTSS given the growing number of seniors and people with disabilities and the LTSS workforce shortage. Although it is unclear how the Medicaid program may change under the Trump Administration and new Congress, state delivery system choices in favor of MLTSS are likely to remain, and the need for LTSS will only continue with the aging of the population. Given the continued state interest in capitated MLTSS programs and Medicaid’s central role in meeting the long-term care needs of seniors and people with disabilities, lessons from states’ experience with § 1115 MLTSS waivers may inform policymakers who are considering implementing or changing these programs.