Medicaid at 50

People with Disabilities

Coverage

While the public is familiar with Medicaid as a health coverage program for low-income children and families, less well recognized is its coverage role for Americans with disabilities. The more than 10 million children and adults who qualify for Medicaid based on disability include individuals with physical impairments and conditions such as cerebral palsy, epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, and multiple sclerosis; spinal cord and traumatic brain injuries; severe mental health conditions, such as depression and schizophrenia; intellectual and developmental disabilities, including Down Syndrome and autism; and other functional limitations. Medicaid’s role for people with disabilities is large because poverty and disability are correlated. In addition, individuals with disabilities have limited access to commercial insurance, which, in any case, typically does not cover the full scope of services that many need. State Medicaid programs cover a wide range of long-term services and supports for people with disabilities in addition to comprehensive acute health care services.

Medicaid’s broad coverage of individuals with disabilities today is the result of federal legislative action going back to the early 1970s, state pursuit and wide use of waiver authority to implement limited expansions, and the convergence of developments in Medicaid, disability rights, and community integration efforts. Under the original Medicaid law, people with disabilities were covered by Medicaid only if they received cash assistance under the state-based welfare system then in place for extremely poor aged, blind, and disabled (ABD) individuals. Some states also used the optional authority to offer Medicaid to medically needy individuals in these groups. The Social Security Amendments of 1972 established the federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, replacing state standards for cash assistance for the ABD population with national eligibility criteria and income standards equivalent to roughly 74% FPL, and the law required states to provide Medicaid for either all federally qualified SSI beneficiaries or all individuals who would qualify for SSI under the state’s eligibility standards in effect in 1972. (Most states elected to provide Medicaid for the entire federally qualified SSI population.) The national standards substantially raised eligibility levels in many states.

The 1972 Amendments also extended Medicare coverage to nonelderly individuals with disabilities but imposed a 29-month waiting period before Medicare benefits begin. Medicaid covers low-income individuals during this waiting period and, after their Medicare benefits begin, it continues as a Medicare supplement, assisting these “dually eligible” enrollees with their Medicare premiums and cost-sharing. For the majority of dual eligible beneficiaries, Medicaid also covers services that Medicare does not cover – most notably, long-term services and supports and, in some states, dental care, eyeglasses and vision care, and hearing aids and services. About 40% of all Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities are dual eligible enrollees.1 These roughly 4 million individuals, who have involved needs for both acute and long-term care, are among the most vulnerable beneficiaries in both Medicare and Medicaid. Although Medicare is the primary payer for dual eligible beneficiaries, Medicaid finances all their long-term care and about 40% of combined Medicare and Medicaid spending for all the services they receive, not including Medicaid payments for Medicare premiums.2

In 1982, Congress expanded access to Medicaid coverage for children with significant disabilities, establishing the so-called “Katie Beckett” option, which makes it possible for children with disabilities who would otherwise be eligible for Medicaid only if they were receiving care in an institution to remain at home with their families. In states with Katie Beckett programs, and under waivers in other states that permit enrollment caps, parents’ income and assets are disregarded in determining Medicaid eligibility for disabled children living at home, exactly as they are for disabled children in institutional care. Because of this Medicaid coverage pathway, many disabled children in middle-income families are also able to access comprehensive services under EPSDT, which supplement any private health insurance they may have. All but a few states have opted to implement a Katie Beckett program or a waiver to accomplish a similar result.3

In 1986, Congress took action to provide employment support for adults with disabilities, passing legislation that required states to continue Medicaid coverage for working disabled individuals who lose their eligibility for SSI due to earnings. In the late 1990s, Congress established new options permitting states to provide Medicaid eligibility for working individuals with disabilities with higher earnings and resources up to state-defined limits and to charge income-related premiums and cost-sharing.4 5 These new Medicaid “buy-in” options were a response to the limitations of job-based health insurance, which is designed for a generally healthy workforce, and also to the fact that employers have disincentives to add high-cost workers to their risk pools. The vast majority of states have adopted “buy-in” options or accomplished a similar purpose under broader section 1115 waivers.6

Over time, expansion in the scope of Medicaid benefits for people with disabilities has also increased the importance of the program for this population. While Medicaid benefits always included skilled nursing facility and home health services, in 1971, Congress established a new state option to cover the services of intermediate care facilities (ICFs) and intermediate care facilities for the intellectually and developmentally disabled (ICFs/IDD). This change enabled states to obtain federal matching funds to help finance services they previously funded with state-only dollars and, in the same stroke, moved the Medicaid program into financing nursing home care for people with disabilities.7

A decade later, in 1981, Medicaid’s role in long-term care entered a new phase when Congress created a new waiver authority in Medicaid (section 1915(c)) that allowed states to cover a wide range of long-term services and supports at home and in community settings for beneficiaries who would otherwise require care in an institution. Using this waiver authority, states can offer services that Medicaid does not cover in general and that may not be medical in nature, and they can target services to subpopulations, such as people with mental illness, cognitive disabilities, or physical disabilities. States can also cap enrollment in section 1915(c) waiver programs. (Under regular Medicaid rules, states generally cannot limit benefits to certain groups or cap participation.) Among the kinds of services that states provide under section 1915(c) waivers are case management, homemaker services, personal care, home modifications, transportation, respite care, and services to transition people from institutions to their homes and communities.8 All states now offer home and community-based services under section 1915(c) waivers or, in a limited number of cases, section 1115 waivers.

Another watershed in the evolution of Medicaid’s role for people with disabilities was the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Olmstead v. L.C. in 1999. The Court ruled that unjustified institutionalization of individuals with disabilities is illegal discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act, a decision leading states to expand access to community-based services. Although Olmstead did not require any change in Medicaid law, the Medicaid program became a key vehicle for Olmstead’s implementation because of its large role in financing long-term services and states’ broad authority to define and design benefits. Indeed, it is fair to say that Medicaid has been the principal engine of expanded access to home and community-based services that make independent living and community integration possible for people with disabilities as well as elderly Americans.9

Impact

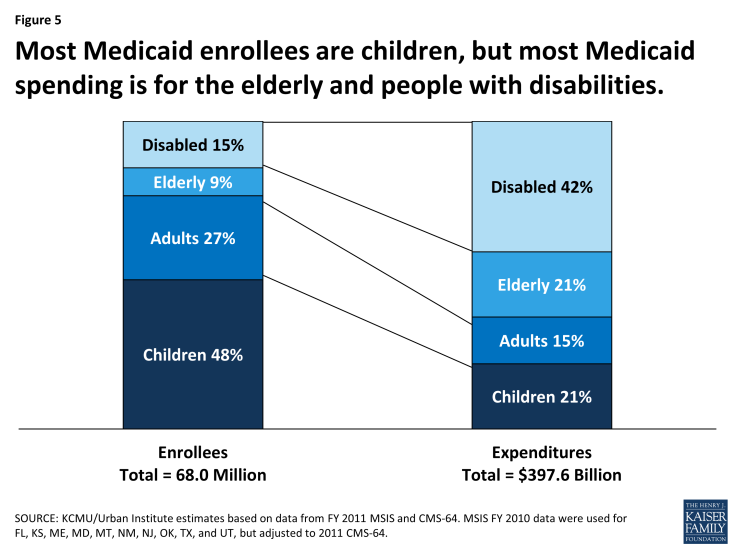

Medicaid’s broad eligibility and benefits for people with disabilities explain the program’s large impact on access to care for this population. Medicaid benefits span preventive services, primary and specialist care, and prescription drugs, as well as medical equipment, assistive technology, and long-term care services essential to the well-being of people with diverse disabilities and needs. Neither private insurance nor Medicare covers a similar range of services or provides comparable financial protection. Although Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities make up only 15% of all enrollees, they account for more than 40% of total Medicaid spending (Figure 5). High Medicaid spending on their behalf reflects their intensive use of both acute and long-term services and the high cost of these services. On a per-enrollee basis, Medicaid spending for people with disabilities is more than five times the level for nonelderly, nondisabled adults and nearly seven times the level for children. Notably, long-term services and supports account for close to 40% of Medicaid spending for beneficiaries with disabilities.10

Figure 5: Most Medicaid enrollees are children, but most Medicaid spending is for the elderly and people with disabilities.

National data show that people with disabilities who are covered by Medicaid are as likely as their counterparts with Medicare or private insurance to have a regular doctor and that they are less likely to have unmet needs overall and unmet needs due to cost.11 Not surprisingly, however, rates of unmet need are higher among Medicaid enrollees with disabilities than among other Medicaid enrollees, and greater disability is associated with greater access difficulties.12 Obstacles like physical inaccessibility of facilities and equipment and lack of transportation are key impediments to access to care for people with disabilities.13

The impact of Medicaid on access to long-term care for low-income people with disabilities is hard to overestimate, as it is essentially the only public or private program that covers this care. Responding to Olmstead, beneficiary preferences, and a growing menu of state options and federal incentives, state Medicaid programs have significantly expanded access to community-based long-term services and have steadily shifted more of their long-term care spending to home and community-based settings, especially in the last 20 years. Nationally, roughly 80% of nonelderly Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities who use long-term services and supports now receive services in the community rather than in institutions.14 At the same time, also as a consequence of states’ choices, not everyone who qualifies for Medicaid and needs home and community-based services can gain access to this care. The ACA sought to increase access to home and community-based care by expanding an existing state option to provide these services as a regular Medicaid benefit, rather than under waivers. The state option approach requires states to provide the services statewide for all income-eligible beneficiaries, subject to medical necessity, and it prohibits enrollment caps and waiting lists. Notably, relatively few states have taken up the state plan option, indicating that states may find the flexibility that waivers give them to control spending by using restrictive financial and functional eligibility standards, limiting enrollment, and capping services worth the process of obtaining and renewing their waivers. In 2013, more than half a million people were on waiting lists for section 1915(c) waiver programs and the average waiting time exceeded two years.15 16

Beyond providing access to care and out-of-pocket protection for people with disabilities, Medicaid eligibility and benefits for this population have also advanced major societal purposes. Due to the Katie Beckett option, many children with significant disabilities can remain with their families and receive services at home or in community settings. Working adults with disabilities with modest earnings can retain their Medicaid coverage or buy it at low cost, an outcome that promotes independent living and more integrated workplaces and communities. More generally, the availability of home and community-based services in Medicaid prevents unnecessary and unwanted institutionalization of people with physical impairments, severe mental illnesses, developmental and intellectual disabilities, and other disabling conditions, and fosters community integration as required by law and desired by many Medicaid beneficiaries and the American public broadly.