Medicaid at 50

Medicaid’s Role in Health Care Financing

As the health coverage program for more than 1 in 5 nonelderly Americans and the main payer for long-term care, Medicaid is a core source of financing in our health care system. It plays an especially large financing role in certain domains. The program provides substantial financing for the health care safety-net – Medicaid payments account for 35% of safety-net hospitals’ revenues and 40% of health center revenues.1 2 Medicaid also finances one-quarter of all behavioral health care spending nationally.3 The program pays for nearly half of all births in the U.S. and plays a singular role in financing health care for women and children. Medicaid also pays half the national bill for long-term services and supports needed by people with disabilities and the elderly. Overall, Medicaid finances $1 of every $6 of personal health spending nationally.

The lion’s share of Medicaid spending – nearly two-thirds – is attributable to people with disabilities (42%) and elderly beneficiaries (21%), although they make up just one-quarter of all Medicaid enrollees. Dual eligible enrollees make up 14% of all beneficiaries, but these nearly 10 million seniors and people with disabilities drive 40% of all Medicaid spending. As these figures help to illustrate, Medicaid is an expensive program because it finances the high per-enrollee costs of care for many Americans with the most extensive needs for health care and long-term care services. For other populations, such as children and nondisabled adults, Medicaid provides coverage at a low per-enrollee cost relative to other payers.4 Growth in aggregate Medicaid spending over time is driven primarily by increasing enrollment in the program due to coverage expansions, demographic trends, and economic conditions. On a per-enrollee basis, however, Medicaid spending has been growing more slowly than private insurance premiums and national health spending per capita.5

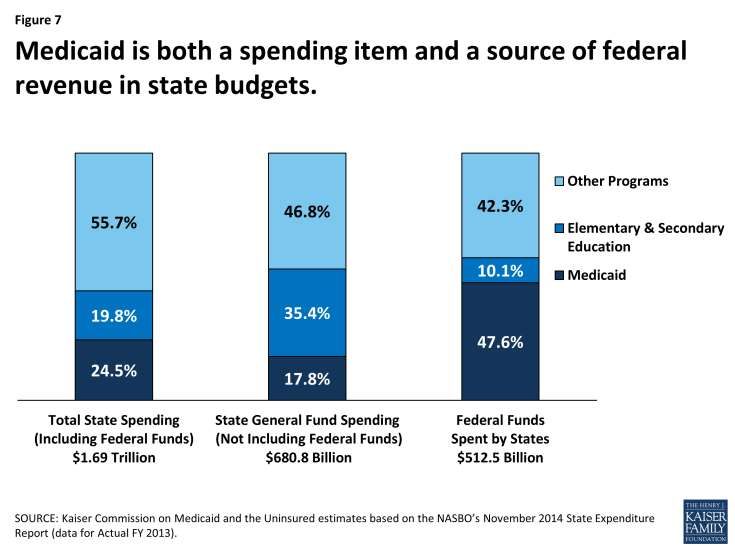

Under the federal-state Medicaid partnership, the federal government matches state Medicaid spending. Thus, Medicaid is a source of both spending and revenue for states (Figure 7). Indeed, the program is the largest source of federal funds flowing to states. The federal match rate for state Medicaid spending associated with enrollees who are eligible under pre-ACA rules ranges from a floor of 50% to 74% in the poorest state, and the federal share of Medicaid spending overall is 57%.6 However, the federal government pays almost the full cost of the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income nonelderly adults (100% through 2016 and phasing down to 90% thereafter). This and other enhanced matching rates for certain other populations under the ACA will increase the average federal share for Medicaid in the next 10 years to between 62% and 64%, depending on the year.7

By federal law, the federal government also matches state spending for “DSH” payments, supplemental payments to hospitals known as disproportionate share hospitals because they serve large numbers of Medicaid and uninsured patients. Federal matching payments for DSH are capped and each state receives an allotment. Beyond minimum federal standards, states have considerable discretion to define hospitals that qualify for DSH payments and to allocate DSH dollars among them. For many safety-net hospitals, Medicaid DSH payments are a critical stream of operating revenues that help subsidize the substantial uncompensated care these institutions provide to uninsured and underinsured people. The ACA called for reduced federal DSH allotments beginning in 2014 corresponding with anticipated increases in coverage and reductions in uncompensated care costs under the new law, and the ACA also called for targeting of the reductions to better achieve the purposes of DSH payments. Due to concerns about potential funding issues for safety-net hospitals that have relied heavily on DSH funds, Congress has delayed implementation of the DSH cuts until FY 2018.

Access to federal Medicaid matching funds has helped to spur state expansions of health coverage for their uninsured residents. It has also provided support for state actions like raising provider payment rates and adding new benefits and helped states with higher Medicaid costs stemming from medical inflation. Federal matching funds have also enabled states to free up their own revenues by, for example, shifting mental health spending previously financed with state-only funds into Medicaid. In addition, because federal funding for Medicaid is available as needed, Medicaid can expand as a safety-net when economic downturns, epidemics, or disasters such as 9/11 or Hurricane Katrina create new needs for coverage. As responsive as this structure is, though, it does not accommodate heightened state fiscal pressures that occur when the local or national economy contracts, leading to increased Medicaid enrollment just when state revenues are declining. Struggling with recessionary budget pressures, states have frequently sought to constrain Medicaid spending by cutting benefits or provider payment rates. Many have made the case that the matching system needs an adjustment to deal with this countercyclical dynamic. Twice, in hard economic periods, Congress has raised the federal match rate to provide additional support to states.

Regardless of the prevailing budget environment, Medicaid spending and financing issues have always produced pressures and tension between the federal government and the states. Although state spending and cost-containment pressures are most acute during economic downturns, rising Medicaid spending is a standing issue for states because they pay a significant share of program costs and must balance their budgets every year. At times, states have sought to maximize federal Medicaid funds in ways not intended by Congress to artificially inflate the federal share of Medicaid spending, sometimes using legal financing mechanisms, including DSH payments, provider taxes as a source of state Medicaid funds, and intergovernmental transfers. Such state practices, which erode the integrity of the matching structure, have fueled concerns about open-ended federal matching funds and the impact on federal Medicaid spending, and led Congress to pass a series of laws clamping down on inappropriate state uses of federal funds.

More fundamental debate about the very structure of Medicaid financing has flared periodically, often within the larger frame of federal deficit reduction discussions. Some policy makers have proposed to convert Medicaid from an entitlement with guaranteed federal matching dollars to a block grant program with caps on federal funding and increased state flexibility to decide who and what to cover. Several analyses that have modeled the potential impact of these approaches indicate that they could shift substantial costs to states, beneficiaries, or providers, and/or lead to reductions in coverage or benefits, but the debate over federal versus state financing and how to contain costs for both the federal and state governments is ongoing.8,9