Medicaid at 50

Service Delivery and Payment Systems and Health Care Innovation

Medicaid enrollees obtain care in an array of settings and systems. Most get their acute medical care from private office-based physicians, but 1 in 7 Medicaid beneficiaries obtain care in community health centers and clinics.1 Most health centers, in addition to providing preventive and primary care, offer a more complete array of services than office-based providers, including behavioral health care and dental services, as well as enabling services needed by many in the low-income population, such as translation, transportation, and referral to community-based social services. Health centers have been shown to perform as well as or better than private physician practices on ambulatory care quality measures.2 Public and other safety-net hospitals, including academic medical centers, are the backbone of emergency and tertiary care for Medicaid beneficiaries; at the same time, these institutions are also the hub of access to trauma, burn, and other highly specialized care for the wider community. Nursing homes and providers of home and community-based services and supports serve Medicaid beneficiaries with long-term care needs.

Also important to Medicaid because of the complex needs of many of its beneficiaries are providers of highly specialized services and supplies, including rehabilitation services, durable medical equipment, assistive technology, and other care. The Medicaid program is a major source of support for these specialized providers because Medicaid beneficiaries make up a large share of the populations they serve and because private insurance does not typically cover their services and supplies to the same extent, if at all.

Because of the high needs of the beneficiary population and the large public investment in Medicaid, the federal government and states have a major stake in the access, quality, and cost of the delivery systems that serve Medicaid enrollees. As large purchasers of services, Medicaid programs also have considerable leverage to shape these systems. Over time, states have used flexibility built into Medicaid as well as waivers to develop innovative approaches to organizing and delivering health and long-term care. Increasing sophistication in states’ and health care systems’ use of data analytics to manage risk and clinical care has aided their efforts. In addition, the ACA has fostered delivery system reform activity in Medicaid through the creation of the Innovation Center in CMS and new federal funding opportunities, demonstrations, and state options in Medicaid. CMS’ State Innovation Model (SIM) initiative to promote multi-payer reform strategies specifically leverages Medicaid, harnessing the program’s experience and innovation in serving high-risk populations and its clout as a large payer. CMS has also established the Medicaid Innovation Accelerator Program, which is providing technical assistance resources to states to further support innovation. States are adopting a multitude of models and targeting different populations in their initiatives, but there are common threads – expansion of managed care; a central role for primary care and medical homes, emphasizing care coordination for enrollees with complex needs; greater integration of services; expanded access to community-based long-term services; and a sharpening focus on quality measurement and high performance.

Managed care

The most prominent dynamic in the evolution of health care delivery and payment systems in Medicaid has been the expansion of risk-based managed care in place of the traditional fee-for-service system. States have pursued risk-based contracting with managed care plans for different purposes, seeking to constrain Medicaid spending, increase budget predictability, improve access to care, and meet other objectives. Medicaid managed care got off to a troubled start in the early 1970s with an initiative in California that demonstrated the perils of a poorly regulated program – capitation rates too low to attract mainstream plans, fraudulent marketing, inadequate access to care, and poor quality.3 4 The scandal gave rise to federal legislative changes and a regulatory framework for Medicaid managed care that requires comprehensive beneficiary protections and avenues for recourse, sound payment rates, adequate provider networks and access to care, and data reporting by plans and states.

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw substantial growth in Medicaid managed care enrollment as states sought to accommodate growing Medicaid enrollment during a time of fiscal pressures. In this period, states were more concerned with managing costs than managing care. Over time, managed care has grown as states have expanded their programs to include wider geographic areas and additional beneficiary groups and shifted from voluntary to mandatory enrollment models.5 6 7 As of 2015, 38 states and DC have risk-contracting programs, and more than half of all Medicaid beneficiaries nationally are enrolled in comprehensive managed care plans, many on a mandatory basis.

Historically, states largely limited managed care to pregnant women, children, and parents, but they are increasingly including Medicaid beneficiaries with complex needs, including persons with disabilities and elderly enrollees. People who use the most services can experience the most fragmentation, gaps, and redundancies in care and can potentially benefit most from managed care. However, they are also the most exposed to the risk of underservice inherent in capitated systems and may have difficulty navigating managed care and gaining access to needed providers and services. State experience covering higher-need populations through managed care is generally limited and most managed care plans have not typically served them. Thus, the adequacy of provider networks and plan capabilities to handle more complex care needs, and rigorous state and federal oversight of access and quality, are crucial issues as Medicaid programs move in this direction. Medicaid managed care programs and oversight vary widely from state to state, and evidence about the impact of managed care on access to care and costs is both limited and mixed.8 9 10 11 The continued expansion of managed care in Medicaid despite the absence of systematic evidence that it improves access or lowers costs is a serious concern, deepened by the lack of managed care data, analysis, and oversight at the federal level.12, 13 After more than a decade, CMS is developing new Medicaid managed care regulations.14 The new rules could strengthen current requirements on states and plans, but ultimately their traction will hinge on effective state and federal enforcement.

Medical homes, health homes, and integration of services

While risk-based managed care dominates the Medicaid delivery system reform landscape, not all states contract with plans, and other innovative and complementary strategies designed to improve care are prevalent in the program. At least half the states have implemented primary care medical homes and pay fee-for-service providers an extra monthly amount to coordinate and monitor primary care services (and sometimes provide additional services for their Medicaid patients). Primary care medical homes may also be implemented in the context of managed care plans.15 Other state approaches build on the medical home model but involve coordination across a broader spectrum of services. Medicaid “health homes” operating in more than a dozen states coordinate physical, behavioral, and long-term care, as well as family supports and social services, for beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions or a serious mental illness.16 Improving the coordination and quality of care for these high-need, high-cost beneficiaries is a major focus of federal and state delivery system innovation efforts in Medicaid (as well as other public programs). These efforts aim to address the fragmentation of care as well as reduce Medicaid costs through lower rates of preventable hospital and nursing home care.

Many Medicaid beneficiaries have comorbid physical and behavioral health conditions and improving the management of their care has been a focal area of delivery system reform activity. In recent years, a majority of states have undertaken initiatives to integrate physical and behavioral health services.17 One innovative approach that several states have implemented is to designate community mental health centers and other mental health entities as Medicaid health homes for beneficiaries with mental illness, based on an assessment that these providers have the appropriate expertise and are in the best position to coordinate services and supports for this population. In the managed care environment, many states are now integrating behavioral health services previously “carved out” from plans into their comprehensive risk-based contracts to promote more holistic care and consolidate accountability.

Long-term services and supports

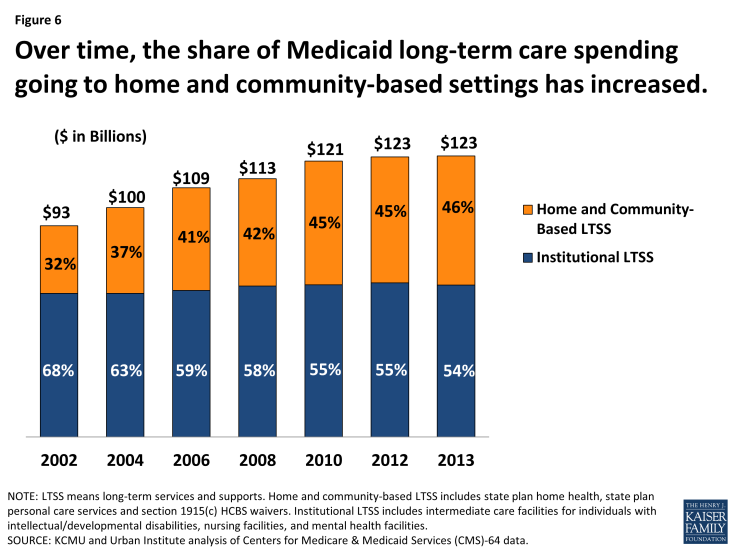

Medicaid’s contribution to delivery system transformation is nowhere more significant than in the long-term care arena. As the principal source of coverage and payment for long-term services for Americans, the Medicaid program has essentially shaped the delivery system. Medicaid financing is essential to the nation’s nursing homes. At the same time, the program has facilitated the dramatic expansion of access to home and community-based long-term services and supports as states have invested and shifted more long-term care spending to non-institutional settings.18 By 2013, 46% of all Medicaid long-term care spending was for home and community-based services, compared to 32% in 2002 (Figure 6). These services underpin independent living and community integration of individuals with disabilities and the elderly.

Figure 6: Over time, the share of Medicaid long-term care spending going to home and community-based settings has increased.

A developing branch of innovation is the delivery of long-term care benefits through managed care arrangements. Under CMS-approved waivers, about 20 states are now operating managed long-term services and supports programs, generally statewide, and nearly all of these states require nonelderly adults with physical disabilities and seniors to enroll in managed care to receive services.19 Most of the programs provide for comprehensive Medicaid benefits, including acute care and behavioral health services as well as nursing facility and home and community-based care, breaking new ground in efforts to more fully integrate care for individuals with long-term needs. But the extensive needs and special vulnerabilities of the beneficiaries involved, and the unfamiliar terrain of managed care for most, raise new concerns and call for strong beneficiary supports and protections, such as assistance choosing plans and measures to maximize continuity of care during the transition to managed care. Managed care plans new to providing long-term services and supports, and long-term providers new to managed care, have a challenging learning curve to climb.

Probably the most challenging and ambitious innovation projects in Medicaid are the state demonstrations proceeding under the ACA initiative to align Medicare and Medicaid financing and coordinate service delivery for dual eligible enrollees. All but two of the 11 states currently slated to move ahead with financial alignment demonstrations rely on capitated managed care plans to coordinate the full complement of Medicare and Medicaid services.20 These demonstrations hold potential to enhance the quality and cost-effectiveness of the care that dual eligible beneficiaries receive. However, uneven levels of state experience serving dual eligible enrollees through managed care, uneven levels of plan experience in the Medicaid and Medicare markets, especially with long-term services and supports, and variable plan quality highlight significant issues surrounding the implementation of these reforms for this very poor and uniquely frail population.21

Quality performance

Since its early years, Medicaid has evolved in many states from a passive claims payment program to a more active purchaser that uses its leverage to drive improvements in the quality of care provided to beneficiaries and to foster more accountable systems of care. This evolution has proceeded via diverse mechanisms, including managed care, the development and state use of quality metrics in Medicaid, and integrated delivery systems and innovative payment approaches that reward providers for high quality performance.22 Quality improvement in the nation’s public health coverage programs is also a major federal priority and focus of increased investment. However, the Medicaid quality enterprise is very much a work in progress. Not all states are engaged. State-level technical, analytic, and financial capacity and resources to pursue quality initiatives are limited and there are many competing priorities both within and outside Medicaid. It bears noting that the development of metrics to assess the quality of care received by people with disabilities is in its infancy. Measures to assess and monitor access and outcomes across settings in managed long-term care programs are needed as well.23