Medicaid at 50

Julia Paradise, Barbara Lyons, and Diane Rowland

Published:

Introduction

The Medicaid program, signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on July 30, 1965, will reach its 50th anniversary this year, a historic milestone. At the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, where we have closely studied and analyzed Medicaid for nearly 25 years, we are recognizing this important occasion by documenting Medicaid’s evolution and its role in our health care system today. This report reflects on Medicaid’s accomplishments and challenges and considers the issues on the horizon that will influence the course of this major health coverage and financing program moving forward.

Established along with Medicare by the Social Security Amendments of 1965, and authorized as Title XIX of the Social Security Act, Medicaid was initially designed as a federal-state program to cover medical expenses for aged, blind, and disabled individuals and parents and dependent children receiving public assistance. Medicaid’s hybrid structure, which involves a mix of federal and state financing and control, is, in many respects, the defining feature of the Medicaid program, and the contrast to Medicare, a national program governed by federal standards and rules and financed entirely by the federal government, is striking. The federal-state Medicaid partnership has served to advance a variety of both federal and state goals. However, it is also the root source of continual tensions over the balance between federal standards and state flexibility and over Medicaid costs and financing. Medicaid’s federal-state structure has also led to substantial state variation in nearly every domain of Medicaid program design and operation, with large implications for access to coverage and care for low-income Americans.

Medicaid is a voluntary program for states and not all states took it up initially. However, access to federal matching funds to provide health coverage for the uninsured proved to be a strong incentive for states, and, by 1982, all 50 states and the District of Columbia had Medicaid programs in place. Over the last five decades, both Congress and the states have expanded and reformed Medicaid significantly to more effectively cover the nation’s uninsured and underinsured citizens. The Medicaid program now provides health and long-term care coverage to nearly 70 million low-income Americans, including pregnant women, children and parents, people with a wide range of disabilities, poor seniors who are also covered by Medicare, and, in states implementing the Medicaid expansion established by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), low-income adults who were previously excluded from the program. Prior to the implementation of the ACA, Medicaid covered roughly half of nonelderly Americans living in poverty. However, because of restrictive eligibility for nonelderly adults and gaps in participation, about half of poor people went without Medicaid coverage.

Medicaid beneficiaries include many of the most disadvantaged individuals in the U.S. in terms of poverty, poor physical and mental health, disability, and lack of social supports. Between its large enrollment and the complex and costly needs of many of its beneficiaries, Medicaid represents a major commitment of federal and state spending. The Medicaid program is the second-largest item in state budgets, after elementary and secondary education, and the third-largest federal domestic program, after Social Security and Medicare. In FY 2013, combined state and federal Medicaid spending totaled $438 billion.

While Medicaid’s coverage role is its most visible aspect, Medicaid’s impact ramifies throughout our health care system. By filling gaps in coverage among people of color, the program plays a key role in advancing health equity. Its comprehensive benefits for prenatal and pediatric care provide a healthy start for millions of American children as well as access to services and supports that are essential to the well-being of children with special needs but not typically covered by commercial insurance. The Medicaid program fills holes left by the private health insurance market, covering people who are priced out of it or do not have access to job-based coverage, and providing broader coverage to many severely disabled and chronically ill individuals. Medicaid also supports poor Medicare beneficiaries and the Medicare program by bearing the high costs of long-term care. And Medicaid revenues provide core funding for our health and long-term care institutions and providers, including safety-net hospitals, emergency departments, health centers, the mental health system, and nursing homes.

Finally, the Medicaid program is a locus of innovation in the health care system. Many states are designing and implementing new models of coordinated and integrated care for people with complex needs that may provide a model for health care delivery beyond the Medicaid context. Medicaid is also the fulcrum of ongoing expansion in access to community-based long-term services and supports that enable individuals with disabilities and older adults who would otherwise require institutional care to live independently in the community.

In the pages that follow, we trace Medicaid’s evolution, discussing major legislative changes and other inflection points in the program’s history, both for the record and for perspective on Medicaid’s different roles in our health care system and how they developed. In doing so, we also show how Medicaid threads through our health care system today and take the measure of its impact. We begin by discussing Medicaid coverage for the main populations served by the program. We then discuss delivery systems and innovation in Medicaid and Medicaid spending and financing. We conclude by looking forward to consider the main issues that will concern the Medicaid program in the decades ahead and to assess how Medicaid is poised to meet the future needs of our nation.

Report

Low-Income Pregnant Women, Children and Families, and Childless Adults

Coverage

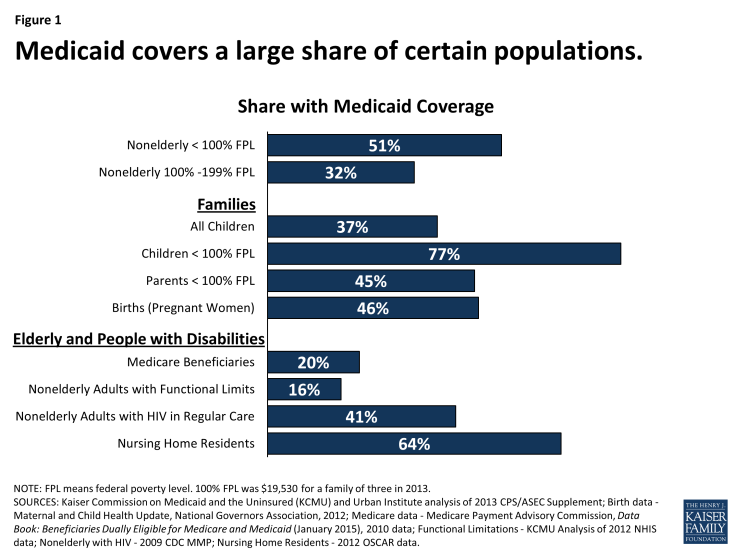

Medicaid’s most well-recognized role in our health care system is as a health coverage program for low-income pregnant women, children, and families. Currently, more than half the states provide Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women with incomes up to at least 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL) (about $40,000 for a family of three in 2015), and the Medicaid program finances almost half of all births. Roughly 33 million children, or more than 1 in 3, are covered by Medicaid (Figure 1).1 Medicaid plays an especially large coverage role for children of color, whose families are more likely to have low income compared to whites, and, as such, the program has reduced racial and ethnic disparities in children’s coverage. Medicaid also serves a large share of children with special health care needs.

Medicaid plays a major but much more limited coverage role for low-income nonelderly adults. In 2013, Medicaid covered over 75% of all children living below the poverty level but just 35% of adults in this income band. The reason for this disparity is two-fold. First, states have historically provided more restrictive eligibility for parents than for children. Second, until the ACA was enacted, nondisabled childless adults under age 65 were categorically excluded from Medicaid by federal law, no matter how poor they were. Prior to the ACA, some states pursued special federal waivers to cover some low-income childless adults under limited expansions of Medicaid. Demonstration waiver authority in section 1115 of the Social Security Act enables HHS to permit states to try approaches that are outside the statutory framework for Medicaid and still receive federal matching funds if the demonstration furthers the objectives of the Medicaid program.

Medicaid’s role in providing health coverage for low-income pregnant women, children and families, and childless adults developed incrementally over time as both federal and state lawmakers expanded the program to cover broader segments of the uninsured population. Under the original 1965 Medicaid law, states were required to provide Medicaid eligibility to poor single parents and children receiving welfare through the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, for which states set the income eligibility thresholds – frequently, well below 50% FPL. States were also granted broad flexibility to provide Medicaid to “medically needy” parents and children with income above the state’s AFDC threshold but high medical expenses relative to their income. Some states used this flexibility to extend coverage to more low-income families. The law also gave states an option to cover children in two-parent families with income up to the state’s AFDC threshold, regardless of whether the family was receiving welfare – so-called “Ribicoff children” for the Senator who authored the provision. This option was used widely by states to expand children’s coverage, and it can be seen as the kernel of later federal reforms that formally decoupled Medicaid eligibility from welfare status and recast Medicaid (for children, families, and, finally, childless adults) as an income-based health coverage program.

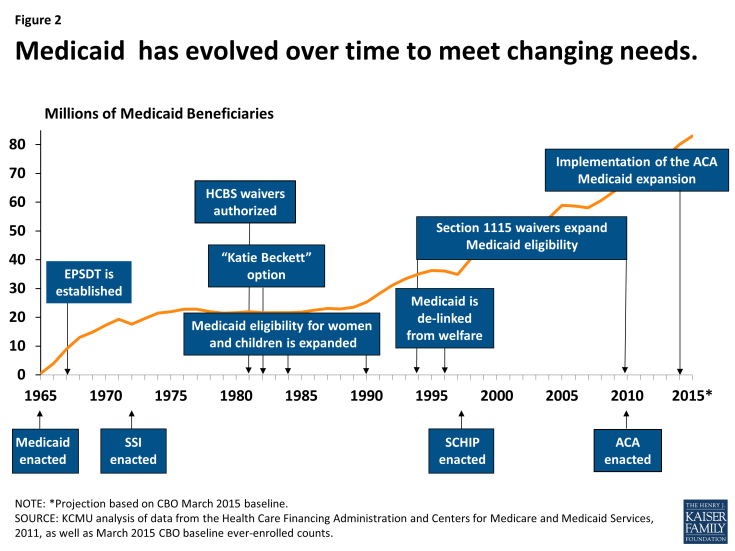

Over time, Congress, through stronger federal minimum requirements, and states, through their requests for and often vigorous take-up of new program options, built on the narrow early Medicaid platform to further expand and improve coverage for children and pregnant women (Figure 2). The Social Security Amendments of 1967 established the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program, Medicaid’s uniquely comprehensive benefit package for children up to age 21, which emphasizes early access to care and regular screenings to assess growth and development. The law required all states to cover EPSDT, overriding previous state-set limits on the amount, duration, and scope of services for children.2 In 1984, Congress moved to require rather than permit states to cover Ribicoff children under age 6 and, responding to concerns about rising infant mortality rates, required coverage of first-time pregnant women up to states’ AFDC thresholds as well.3 Subsequent legislation raised the federal minimum eligibility thresholds for both pregnant women and children, and many states chose to expand Medicaid eligibility beyond the federal minimum levels. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, in response to the still very low eligibility thresholds in place for pregnant women and children in some states, Congress required all states to cover pregnant women and children under age 6 with family income up to at least 133% FPL. Also, in 1989, EPSDT was significantly strengthened.4 In 1990, states were required to phase in Medicaid coverage for school-age children (age 6-18) with family income up to 100% FPL, an expansion that was completed in 2002, establishing Medicaid eligibility for all children in poverty nationwide.

In 1996, in a major federal overhaul of the welfare program, which is now known as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Congress de-linked Medicaid eligibility from welfare eligibility and gave states flexibility to expand income eligibility for Medicaid broadly to cover more working families. Severing Medicaid from its welfare roots fundamentally altered Medicaid, transforming it from a welfare program to a health coverage program for low-income children and families. In 1997, Congress built on Medicaid yet again, establishing the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which provides enhanced federal matching funds to states to cover low-income children above the cut-off for Medicaid through either an expansion of Medicaid or a separate CHIP program. Responding to the high federal match rate and interest in expanding coverage for children, states embraced CHIP and, for the first time, conducted vigorous outreach and enrollment campaigns. In many states, efforts to promote participation in CHIP carried over to Medicaid, marking a sea change in the program’s orientation, from gate-keeping to gate-opening, as far as children were concerned.

While the progression of Medicaid expansions resulted in broad coverage of low-income children, Medicaid coverage of their parents lagged far behind, and the categorical exclusion of most childless adults from Medicaid left even the poorest of these individuals without access to coverage. It was against this backdrop that the ACA ushered in the most recent era of Medicaid expansion. The health reform law expanded Medicaid eligibility to nonelderly adults with income up to a uniform federal threshold of 138% FPL (about $16,250 for an individual in 2015) and provided nearly full federal financing for the cost. This expansion established Medicaid as the health coverage program for nearly all low-income Americans under age 65 within the broader system the ACA created to cover the uninsured.

The ACA also raised the minimum Medicaid eligibility threshold for school-age children to the same level that applies for younger children, eliminating previous age-based differences in minimum eligibility standards, and extended Medicaid coverage for foster care children up to age 26 (paralleling the requirement that private insurers offering dependent coverage for children allow those up to age 26 to remain on their parent’s plan). In addition, the ACA required states to take far-reaching measures to modernize and streamline the Medicaid application, enrollment, and renewal processes to be coordinated with the new Marketplaces.

Unexpectedly, the Medicaid expansion to low-income adults hit a major hurdle in the Supreme Court’s landmark decision on the ACA in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius.5 The Court ruled that the Medicaid expansion was unconstitutionally coercive and the decision limited the HHS Secretary’s enforcement authority, effectively making the expansion optional for states. As of this writing, 29 states and the District of Columbia have adopted the Medicaid expansion, including several recently, and other states are debating the issue, evidence that the picture may continue to evolve.

The federal and state expansions of Medicaid over the last five decades have had a dramatic impact on coverage of low-income children and adults in the U.S. In 2011, almost 33 million children and more than 18 million pregnant women, parents, and other nonelderly, nondisabled adults were enrolled in the program. The greatest impact of Medicaid and CHIP has been on children’s coverage. Between 1997 and 2012, the uninsured rate among children fell by half, from 14% to an historic low of 7%.6 Currently, more than half the states cover children with family income up to at least 250% FPL (about $50,000 for a family of three.)7 The ACA Medicaid expansion has brought coverage to millions of additional uninsured, nonelderly parents and childless adults in the states that have implemented it. Federal data show that, in September 2014, at least 4.6 million low-income adults were covered through the new adult expansion group in the 23 states for which data were available (of 27 states that had adopted the expansion by then).8 This figure does not include an estimated 1.2 million newly eligible adults in California or enrollment in three additional states that have adopted the expansion in the meantime.9

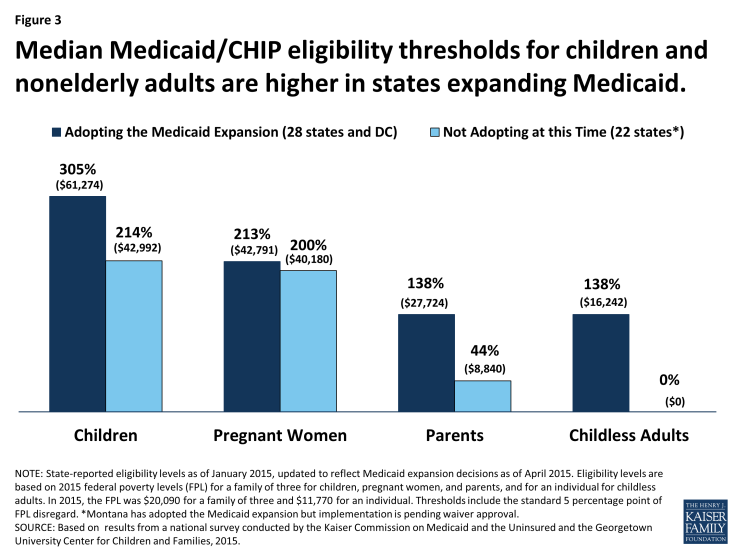

While Medicaid has been instrumental in reducing the number and share of low-income nonelderly Americans without health insurance, the ACA vision of Medicaid as a universal program for this population has yet to be fully realized. In 2013, over 7 million children remained uninsured, of whom an estimated 5.2 million would qualify for Medicaid or CHIP, pointing to needs for targeted outreach and enrollment efforts.10 A more substantial share of adults who would be eligible for Medicaid are not enrolled in the program, again a signal that more intensive and targeted efforts are needed to engage this hard-to-reach population.11 Also, Medicaid and CHIP income eligibility thresholds for children and nonelderly adults in the states not expanding Medicaid lag behind those in the states moving forward (Figure 3). Further, nearly 4 million poor adults in the non-expansion states fall into the “coverage gap” because their income is too high for Medicaid but too low to qualify for premium subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage.12 Notably, Blacks, who reside in high numbers in many of the non-expansion states, disproportionately fall into the coverage gap.13

Figure 3: Median Medicaid/CHIP eligibility thresholds for children and nonelderly adults are higher in states expanding Medicaid.

Impact

The goal of Medicaid coverage is to facilitate access to care for low-income people and to provide financial protection against high out-of-pocket costs for health care. A large body of research shows that the program largely succeeds in this purpose. Still, there remain challenges for Medicaid in facilitating access to care. Many factors bear on access to care, including the scope of Medicaid benefits covered by states, limits on Medicaid premiums and cost-sharing, provider payment and participation in Medicaid, transportation and language barriers, and features of the larger health care ecosystem of which Medicaid is part.

Children

Medicaid’s EPSDT benefits for children up to age 21 are considered a model of pediatric coverage. EPSDT is unusually comprehensive and emphasizes early intervention, before preventable health problems become permanent. Its benefits include immunizations and other preventive and primary care services, prescription drugs, hospital care, vision, dental, and hearing services, diagnostic and treatment services, and all other services permitted under federal Medicaid law. Further, the medical necessity standard that governs EPSDT requires states to cover services to correct or ameliorate the effects of physical and mental illnesses and conditions for children. This expansive definition is designed to ensure robust access to care for low-income children, including access to services and supports such as medical equipment, speech, physical, and occupational therapy, and assistive technology for children with special needs.14 To ensure that financial barriers do not impede their access, premiums are prohibited in Medicaid for children below 150% FPL and cost-sharing is tightly restricted for all children. Although children make up nearly half of all Medicaid beneficiaries, they account for about 20% of Medicaid spending, a reflection of their relatively routine and low-cost health care needs and costs compared to others covered by the program, especially beneficiaries with disabilities and those over age 65.

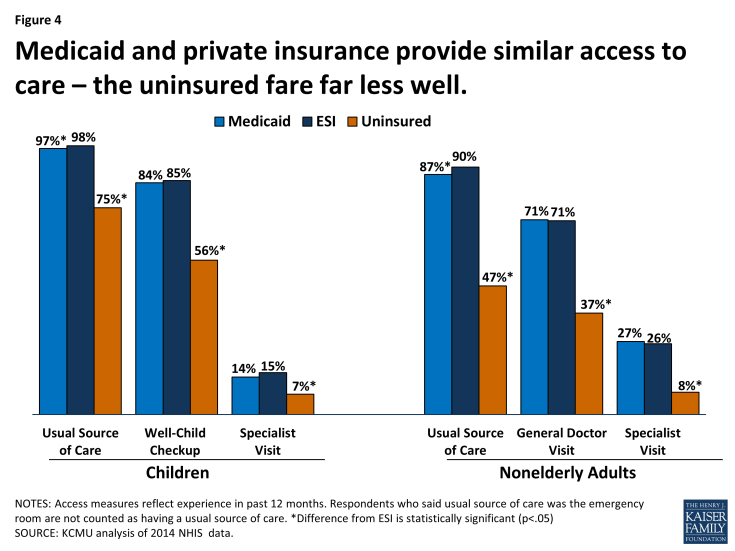

Strong access to primary care among children covered by Medicaid is well-documented (Figure 4).15 16 Nearly all children with Medicaid have a usual source of care, which research shows enhances access to and appropriate use of health care services.17 Compared to uninsured children, children with Medicaid are far more likely to have a usual source of care, visit physicians and dentists, and get recommended preventive care, and they are less likely to have unmet needs for medical, dental, and specialty care and prescription drugs. Furthermore, rates of access to preventive and primary care for children with Medicaid or CHIP are fairly comparable to those for children with employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) despite sharp differences between the health status and demographic and socioeconomic profiles of the two groups. When these differences are controlled, rates of access to specialist care are also similar between publicly insured children and those with ESI.18 Notably, children across the board, including those covered by Medicaid or other types of insurance, get preventive care at rates below recommended levels.

Figure 4: Medicaid and private insurance provide similar access to care – the uninsured fare far less well.

Children’s access to oral health services is a key concern in Medicaid. Since severe problems obtaining dental care for children enrolled in Medicaid came to light in the mid-2000s, CMS and the states have made targeted efforts and investments in this area. Although substantial improvements have resulted, in 2013, the share of Medicaid-enrolled children who received at least one preventive dental service a year exceeded 50% in only half the states.19 Children with private dental coverage are generally more likely to get preventive dental care, but, as with other preventive care, rates of preventive dental care are well below recommended levels for all children.20

While population-level findings on access to care in Medicaid indicate high performance overall, direct studies of access at a local level, using “secret shopper” techniques, show that children with Medicaid or CHIP are much more likely than privately insured children to be denied appointments with specialists and that they face longer waits when they do get appointments.21 These findings, which are consistent with lower rates of provider participation in Medicaid compared to private insurance, are informative about beneficiaries’ care-seeking experience and their more limited choice of providers, but it is important to consider them in the context of consistent evidence of high rates of realized access to care in the Medicaid program overall.22

A growing body of research provides evidence that Medicaid and CHIP coverage confer benefits on children beyond improved access to care. Studies show gains in children’s health and health behaviors, improved performance in school, fewer days of missed school due to illness or injury, and higher long-run educational attainment, including high-school completion, college attendance, and college graduation among children covered by Medicaid in their childhood and youth.23 24 25

Nonelderly Adults

Medicaid law authorizes comprehensive benefits for adults, including physician and hospital care, lab and x-ray services, prescription drugs, and non-emergency medical transportation. Medicaid benefits for reproductive care, including both maternity care and family planning services, and breast and cervical cancer screening and treatment, are extremely important for low-income women, who make up two-thirds of nonelderly adult enrollees, and Medicaid expansions to pregnant women are credited with reductions in infant mortality and low birth weights as well as improved health outcomes for children.26 Whereas federal EPSDT requirements establish a uniformly comprehensive Medicaid benefit package for children nationwide, states have substantial flexibility in defining Medicaid benefits for adults and the range and scope of adult benefits vary widely by state as a result. Benefits for adults in the new Medicaid expansion group must include the 10 categories of “essential health benefits” defined by the ACA, but states retain considerable flexibility to design them. Similar to children, nonelderly adults without disabilities are a low-cost Medicaid population. In 2011, nonelderly, nondisabled adults made up about one-quarter of Medicaid beneficiaries but accounted for a fairly small share of Medicaid spending (15%), reflecting both low Medicaid spending per enrollee and limited Medicaid eligibility for this population.

The empirical findings on adults’ access to care in Medicaid are largely positive. Because of its rigorous design, the recent Oregon Health Insurance Experiment provides particularly strong evidence of Medicaid’s impact. Taking advantage of a 2008 lottery that randomly allocated a limited number of new Medicaid “slots” for low-income uninsured adults, investigators compared access to care and selected health outcomes between the adults who won Medicaid coverage and the adults who did not. Study findings one and two years out from the lottery showed higher use of preventive services and other care, improved self-reported health, and reduced clinical depression among the adults who gained Medicaid coverage compared to the others.27 28 The risk of medical debt also declined significantly in the Medicaid group and catastrophic medical costs were virtually eliminated for them. On the other hand, the observed reductions in blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and blood glucose levels were not statistically significant. On this point, the researchers noted limitations in the study’s statistical power. A separate team of investigators, using cost-effectiveness analysis, found that the Oregon Medicaid expansion was a good public investment, providing a net financial return to society.29

The evidence from studies comparing Medicaid and privately insured adults’ access to care closely mirrors the evidence for children. The vast majority of adults in both insurance groups have a usual source of care. When health, demographic, and socioeconomic differences between the two groups are controlled, Medicaid adults are as likely as the privately insured to have received recommended preventive care, a general doctor visit, and a specialist visit in the past 12 months.30 Research shows that, compared to adults with similar characteristics who have ESI, adults covered by Medicaid have similar rates of delayed and unmet needs for medical care.31 32 Medicaid also affords greater financial protection from medical expenses; it has been projected that adult Medicaid beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket spending would increase more than three-fold if they were covered by ESI instead, even though their expected health care use would not be much different. Again mirroring the findings for children, direct studies of access to care for adults show that physicians are more willing to serve those with private insurance than those with Medicaid coverage.33 34 This pattern has led to concerns about provider availability in Medicaid as more adults gain coverage. Anticipating increased demand for services due to expanded coverage, the ACA temporarily raised Medicaid fees for many primary care services, which are typically very low, to Medicare fee levels to garner greater primary care physician participation in Medicaid. Findings that physician participation rates are higher in states with higher Medicaid payment rates relative to other payers suggest that provider payment rates may be an effective tool for leveraging increased access to care.35

Because major chronic illnesses are prevalent among Medicaid adults and securing access to care is arguably most challenging for those with the greatest needs, the experience of beneficiaries with chronic conditions is an important gauge of access in Medicaid. In this regard, a suite of studies has shown significant and clinically meaningful differences in access and care between nonelderly adults with Medicaid and those who are uninsured. One of the studies, which focused on diabetes, found that adults enrolled in Medicaid were less likely than their uninsured counterparts to report being unable to get needed care, had more office visits and filled more prescriptions, and were more likely to get key elements of recommended diabetes care. The companion analyses looking at cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, and mental illness reached similar findings.36 37 38 39 40

The vast majority of adults who have ever received Medicaid benefits say that their overall experiences have been positive.41 At the same time, there are some areas of serious concern for adult access to care in Medicaid. In particular, while needs for behavioral health care are great among adult Medicaid beneficiaries and demand for these services is likely to grow with the Medicaid expansion, psychiatrist participation in the program is very low and there is a growing workforce crisis in the field of addiction treatment.42 43 Lack of access to dental care is also a major problem. Poor oral health is associated with chronic conditions including diabetes and heart disease and can also interfere with nutrition; poor or missing teeth adversely affect employability as well. Nonetheless, adult dental benefits are optional under federal Medicaid law and they are not included among the ACA’s essential health benefits for newly eligible adults. Most states cover limited or emergency-only dental services for adults, but dental care is very expensive and few Medicaid beneficiaries can afford to pay for it out-of-pocket. Many other benefits, such as eyeglasses and physical therapy, are also optional for adults, and states often drop or cut back on these benefits when they are facing tight budgets.

People with Disabilities

Coverage

While the public is familiar with Medicaid as a health coverage program for low-income children and families, less well recognized is its coverage role for Americans with disabilities. The more than 10 million children and adults who qualify for Medicaid based on disability include individuals with physical impairments and conditions such as cerebral palsy, epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, and multiple sclerosis; spinal cord and traumatic brain injuries; severe mental health conditions, such as depression and schizophrenia; intellectual and developmental disabilities, including Down Syndrome and autism; and other functional limitations. Medicaid’s role for people with disabilities is large because poverty and disability are correlated. In addition, individuals with disabilities have limited access to commercial insurance, which, in any case, typically does not cover the full scope of services that many need. State Medicaid programs cover a wide range of long-term services and supports for people with disabilities in addition to comprehensive acute health care services.

Medicaid’s broad coverage of individuals with disabilities today is the result of federal legislative action going back to the early 1970s, state pursuit and wide use of waiver authority to implement limited expansions, and the convergence of developments in Medicaid, disability rights, and community integration efforts. Under the original Medicaid law, people with disabilities were covered by Medicaid only if they received cash assistance under the state-based welfare system then in place for extremely poor aged, blind, and disabled (ABD) individuals. Some states also used the optional authority to offer Medicaid to medically needy individuals in these groups. The Social Security Amendments of 1972 established the federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, replacing state standards for cash assistance for the ABD population with national eligibility criteria and income standards equivalent to roughly 74% FPL, and the law required states to provide Medicaid for either all federally qualified SSI beneficiaries or all individuals who would qualify for SSI under the state’s eligibility standards in effect in 1972. (Most states elected to provide Medicaid for the entire federally qualified SSI population.) The national standards substantially raised eligibility levels in many states.

The 1972 Amendments also extended Medicare coverage to nonelderly individuals with disabilities but imposed a 29-month waiting period before Medicare benefits begin. Medicaid covers low-income individuals during this waiting period and, after their Medicare benefits begin, it continues as a Medicare supplement, assisting these “dually eligible” enrollees with their Medicare premiums and cost-sharing. For the majority of dual eligible beneficiaries, Medicaid also covers services that Medicare does not cover – most notably, long-term services and supports and, in some states, dental care, eyeglasses and vision care, and hearing aids and services. About 40% of all Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities are dual eligible enrollees.1 These roughly 4 million individuals, who have involved needs for both acute and long-term care, are among the most vulnerable beneficiaries in both Medicare and Medicaid. Although Medicare is the primary payer for dual eligible beneficiaries, Medicaid finances all their long-term care and about 40% of combined Medicare and Medicaid spending for all the services they receive, not including Medicaid payments for Medicare premiums.2

In 1982, Congress expanded access to Medicaid coverage for children with significant disabilities, establishing the so-called “Katie Beckett” option, which makes it possible for children with disabilities who would otherwise be eligible for Medicaid only if they were receiving care in an institution to remain at home with their families. In states with Katie Beckett programs, and under waivers in other states that permit enrollment caps, parents’ income and assets are disregarded in determining Medicaid eligibility for disabled children living at home, exactly as they are for disabled children in institutional care. Because of this Medicaid coverage pathway, many disabled children in middle-income families are also able to access comprehensive services under EPSDT, which supplement any private health insurance they may have. All but a few states have opted to implement a Katie Beckett program or a waiver to accomplish a similar result.3

In 1986, Congress took action to provide employment support for adults with disabilities, passing legislation that required states to continue Medicaid coverage for working disabled individuals who lose their eligibility for SSI due to earnings. In the late 1990s, Congress established new options permitting states to provide Medicaid eligibility for working individuals with disabilities with higher earnings and resources up to state-defined limits and to charge income-related premiums and cost-sharing.4 5 These new Medicaid “buy-in” options were a response to the limitations of job-based health insurance, which is designed for a generally healthy workforce, and also to the fact that employers have disincentives to add high-cost workers to their risk pools. The vast majority of states have adopted “buy-in” options or accomplished a similar purpose under broader section 1115 waivers.6

Over time, expansion in the scope of Medicaid benefits for people with disabilities has also increased the importance of the program for this population. While Medicaid benefits always included skilled nursing facility and home health services, in 1971, Congress established a new state option to cover the services of intermediate care facilities (ICFs) and intermediate care facilities for the intellectually and developmentally disabled (ICFs/IDD). This change enabled states to obtain federal matching funds to help finance services they previously funded with state-only dollars and, in the same stroke, moved the Medicaid program into financing nursing home care for people with disabilities.7

A decade later, in 1981, Medicaid’s role in long-term care entered a new phase when Congress created a new waiver authority in Medicaid (section 1915(c)) that allowed states to cover a wide range of long-term services and supports at home and in community settings for beneficiaries who would otherwise require care in an institution. Using this waiver authority, states can offer services that Medicaid does not cover in general and that may not be medical in nature, and they can target services to subpopulations, such as people with mental illness, cognitive disabilities, or physical disabilities. States can also cap enrollment in section 1915(c) waiver programs. (Under regular Medicaid rules, states generally cannot limit benefits to certain groups or cap participation.) Among the kinds of services that states provide under section 1915(c) waivers are case management, homemaker services, personal care, home modifications, transportation, respite care, and services to transition people from institutions to their homes and communities.8 All states now offer home and community-based services under section 1915(c) waivers or, in a limited number of cases, section 1115 waivers.

Another watershed in the evolution of Medicaid’s role for people with disabilities was the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Olmstead v. L.C. in 1999. The Court ruled that unjustified institutionalization of individuals with disabilities is illegal discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act, a decision leading states to expand access to community-based services. Although Olmstead did not require any change in Medicaid law, the Medicaid program became a key vehicle for Olmstead’s implementation because of its large role in financing long-term services and states’ broad authority to define and design benefits. Indeed, it is fair to say that Medicaid has been the principal engine of expanded access to home and community-based services that make independent living and community integration possible for people with disabilities as well as elderly Americans.9

Impact

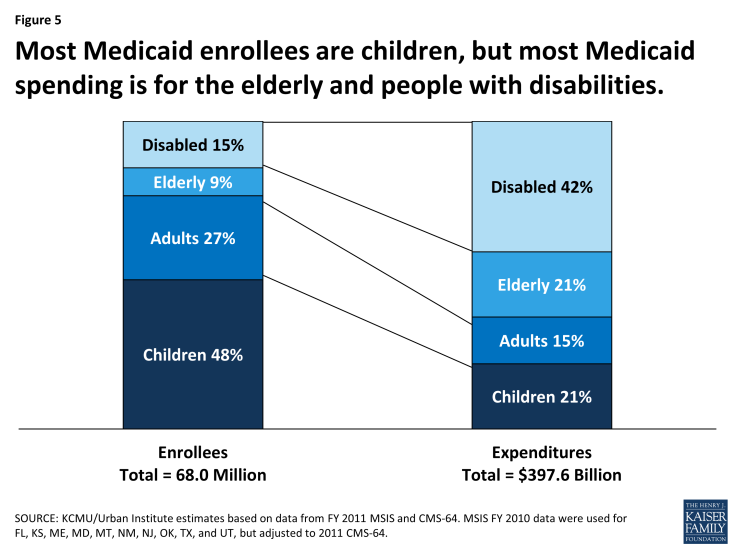

Medicaid’s broad eligibility and benefits for people with disabilities explain the program’s large impact on access to care for this population. Medicaid benefits span preventive services, primary and specialist care, and prescription drugs, as well as medical equipment, assistive technology, and long-term care services essential to the well-being of people with diverse disabilities and needs. Neither private insurance nor Medicare covers a similar range of services or provides comparable financial protection. Although Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities make up only 15% of all enrollees, they account for more than 40% of total Medicaid spending (Figure 5). High Medicaid spending on their behalf reflects their intensive use of both acute and long-term services and the high cost of these services. On a per-enrollee basis, Medicaid spending for people with disabilities is more than five times the level for nonelderly, nondisabled adults and nearly seven times the level for children. Notably, long-term services and supports account for close to 40% of Medicaid spending for beneficiaries with disabilities.10

Figure 5: Most Medicaid enrollees are children, but most Medicaid spending is for the elderly and people with disabilities.

National data show that people with disabilities who are covered by Medicaid are as likely as their counterparts with Medicare or private insurance to have a regular doctor and that they are less likely to have unmet needs overall and unmet needs due to cost.11 Not surprisingly, however, rates of unmet need are higher among Medicaid enrollees with disabilities than among other Medicaid enrollees, and greater disability is associated with greater access difficulties.12 Obstacles like physical inaccessibility of facilities and equipment and lack of transportation are key impediments to access to care for people with disabilities.13

The impact of Medicaid on access to long-term care for low-income people with disabilities is hard to overestimate, as it is essentially the only public or private program that covers this care. Responding to Olmstead, beneficiary preferences, and a growing menu of state options and federal incentives, state Medicaid programs have significantly expanded access to community-based long-term services and have steadily shifted more of their long-term care spending to home and community-based settings, especially in the last 20 years. Nationally, roughly 80% of nonelderly Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities who use long-term services and supports now receive services in the community rather than in institutions.14 At the same time, also as a consequence of states’ choices, not everyone who qualifies for Medicaid and needs home and community-based services can gain access to this care. The ACA sought to increase access to home and community-based care by expanding an existing state option to provide these services as a regular Medicaid benefit, rather than under waivers. The state option approach requires states to provide the services statewide for all income-eligible beneficiaries, subject to medical necessity, and it prohibits enrollment caps and waiting lists. Notably, relatively few states have taken up the state plan option, indicating that states may find the flexibility that waivers give them to control spending by using restrictive financial and functional eligibility standards, limiting enrollment, and capping services worth the process of obtaining and renewing their waivers. In 2013, more than half a million people were on waiting lists for section 1915(c) waiver programs and the average waiting time exceeded two years.15 16

Beyond providing access to care and out-of-pocket protection for people with disabilities, Medicaid eligibility and benefits for this population have also advanced major societal purposes. Due to the Katie Beckett option, many children with significant disabilities can remain with their families and receive services at home or in community settings. Working adults with disabilities with modest earnings can retain their Medicaid coverage or buy it at low cost, an outcome that promotes independent living and more integrated workplaces and communities. More generally, the availability of home and community-based services in Medicaid prevents unnecessary and unwanted institutionalization of people with physical impairments, severe mental illnesses, developmental and intellectual disabilities, and other disabling conditions, and fosters community integration as required by law and desired by many Medicaid beneficiaries and the American public broadly.

The Elderly

Coverage

The Medicaid program covers over 6 million low-income elderly Americans, nearly all of whom also have Medicare. This figure translates to more than 1 in every 7 elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Medicaid supplements Medicare for these dually eligible seniors just as it does for dual eligible beneficiaries with disabilities, covering their Medicare premiums and cost-sharing, and, for those with very low income, providing long-term care and, in some states, other benefits such as hearing aids and eyeglasses.

Before the mid-1980s, elderly Medicare beneficiaries could qualify for Medicaid only if they were receiving SSI benefits or met their state’s medically needy standard, but federal legislative action in the late 1980s and early 1990s extended Medicaid protection to more low-income seniors. Congress first gave states an option to provide Medicaid to Medicare beneficiaries with income exceeding SSI levels but below 100% FPL. A couple of years later, in the 1988 Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act, Congress used the Medicaid program to cushion the impact of rising Medicare premiums and cost-sharing for low-income Medicare beneficiaries, requiring all state Medicaid programs to cover these costs for Medicare beneficiaries with income below the poverty level. Although this law was famously repealed a year later, the expansion of Medicaid assistance to provide financial relief for Medicare beneficiaries was preserved. Subsequent legislation provided for partial Medicaid coverage, including assistance with Medicare premiums and cost-sharing but not Medicaid benefits, for elderly Medicare beneficiaries at somewhat higher income levels, who are known as “partial dual eligibles.”1 Three-quarters of elderly dual eligible beneficiaries are entitled to both full Medicaid benefits and financial assistance. Many states also provide Medicaid eligibility for medically needy individuals, and they can use another Medicaid option to cover institutional care for elderly individuals up to a state-set income limit up to 300% of the SSI standard and an asset test.

The most significant way that Medicaid helps the elderly is by paying for long-term care. The program covers close to 2 million elderly beneficiaries who use long-term care services – about 1 million who mostly use institutional care and another 1 million who mostly use home and community-based services and supports.2 On average, nursing home care costs more than $90,000 a year, assisted living facility care costs over $42,000, and typical use of home health aide services and adult day care each cost in the neighborhood of $20,000 a year.3 4 Such large and unpredictable expenses are difficult to save for and, in the absence of other assistance, virtually impossible to shoulder for elderly Americans living on Social Security and barely able to make ends meet.

A persistent myth about Medicaid is that large numbers of Americans with substantial means transfer their assets to get Medicaid to pay for their long-term care. Actually, people seeking Medicaid for nursing home or community-based long-term care are subject to a review of asset transfers going back five years, and Medicaid eligibility for long-term services and supports is limited to people who are impoverished, often by having spent down their own income and resources to pay for such care. In addition, Medicaid beneficiaries must contribute to the cost of care from their monthly income. The fact that long-term care remains unaffordable for most Americans and that there exists almost no assistance for long-term care other than Medicaid is a current and growing concern.

Impact

Medicaid provides crucial services and financial protection for millions of poor elderly Americans. As vital as Medicare is to the elderly, it is not comprehensive coverage and its large benefit gaps and premium and cost-sharing requirements can result in heavy financial burdens and deter Medicare beneficiaries from seeking needed care. For seniors with low or moderate income and limited resources, Medicaid lowers these barriers and provides benefits for nursing home care and community-based long-term services. Still, the goal of enrolling all elderly individuals who qualify for Medicaid has not been fully realized. Lack of awareness and understanding of the assistance Medicaid provides, complex enrollment processes, asset tests, limited federal and state outreach efforts, and beneficiary reluctance to apply for help from a program associated with welfare all contribute to low levels of participation. Navigating and coordinating coverage between Medicare and Medicaid is also a confusing and challenging task for many. Finally, it should be noted that, largely because of the restrictive asset test, Medicaid premium and cost-sharing assistance does not reach all elderly Medicare beneficiaries with very low income; under current eligibility rules, one-quarter of the elderly with income below $10,000 cannot qualify for this help.5

Major chronic conditions, including hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes, are prevalent among elderly dual eligible beneficiaries; nearly one-quarter have Alzheimer’s disease or another kind of dementia and 1 in 5 have depression.6 These conditions entail high and ongoing costs for care. Medicare finances the vast majority of acute care received by elderly dual eligible enrollees, but Medicaid finances 100% of their long-term care. In 2010, Medicaid financed 40% of combined Medicaid and Medicare spending for all services for elderly dual eligible enrollees, not including Medicaid payments for Medicare premiums.7

Largely because of their high use of long-term services and supports and the high cost of this care, the elderly, who make up just under 10% of all Medicaid beneficiaries, drive roughly 20% of Medicaid spending. Long-term care accounts for close to three-quarters of total Medicaid spending for the elderly. Half of all elderly Medicaid beneficiaries who use long-term care are receiving care in nursing homes or other institutions, but half are now receiving services and supports at home or in the community, evidence that Medicaid’s beneficial impact on independent living and community integration extends to older Americans as well as individuals with disabilities.8

Service Delivery and Payment Systems and Health Care Innovation

Medicaid enrollees obtain care in an array of settings and systems. Most get their acute medical care from private office-based physicians, but 1 in 7 Medicaid beneficiaries obtain care in community health centers and clinics.1 Most health centers, in addition to providing preventive and primary care, offer a more complete array of services than office-based providers, including behavioral health care and dental services, as well as enabling services needed by many in the low-income population, such as translation, transportation, and referral to community-based social services. Health centers have been shown to perform as well as or better than private physician practices on ambulatory care quality measures.2 Public and other safety-net hospitals, including academic medical centers, are the backbone of emergency and tertiary care for Medicaid beneficiaries; at the same time, these institutions are also the hub of access to trauma, burn, and other highly specialized care for the wider community. Nursing homes and providers of home and community-based services and supports serve Medicaid beneficiaries with long-term care needs.

Also important to Medicaid because of the complex needs of many of its beneficiaries are providers of highly specialized services and supplies, including rehabilitation services, durable medical equipment, assistive technology, and other care. The Medicaid program is a major source of support for these specialized providers because Medicaid beneficiaries make up a large share of the populations they serve and because private insurance does not typically cover their services and supplies to the same extent, if at all.

Because of the high needs of the beneficiary population and the large public investment in Medicaid, the federal government and states have a major stake in the access, quality, and cost of the delivery systems that serve Medicaid enrollees. As large purchasers of services, Medicaid programs also have considerable leverage to shape these systems. Over time, states have used flexibility built into Medicaid as well as waivers to develop innovative approaches to organizing and delivering health and long-term care. Increasing sophistication in states’ and health care systems’ use of data analytics to manage risk and clinical care has aided their efforts. In addition, the ACA has fostered delivery system reform activity in Medicaid through the creation of the Innovation Center in CMS and new federal funding opportunities, demonstrations, and state options in Medicaid. CMS’ State Innovation Model (SIM) initiative to promote multi-payer reform strategies specifically leverages Medicaid, harnessing the program’s experience and innovation in serving high-risk populations and its clout as a large payer. CMS has also established the Medicaid Innovation Accelerator Program, which is providing technical assistance resources to states to further support innovation. States are adopting a multitude of models and targeting different populations in their initiatives, but there are common threads – expansion of managed care; a central role for primary care and medical homes, emphasizing care coordination for enrollees with complex needs; greater integration of services; expanded access to community-based long-term services; and a sharpening focus on quality measurement and high performance.

Managed care

The most prominent dynamic in the evolution of health care delivery and payment systems in Medicaid has been the expansion of risk-based managed care in place of the traditional fee-for-service system. States have pursued risk-based contracting with managed care plans for different purposes, seeking to constrain Medicaid spending, increase budget predictability, improve access to care, and meet other objectives. Medicaid managed care got off to a troubled start in the early 1970s with an initiative in California that demonstrated the perils of a poorly regulated program – capitation rates too low to attract mainstream plans, fraudulent marketing, inadequate access to care, and poor quality.3 4 The scandal gave rise to federal legislative changes and a regulatory framework for Medicaid managed care that requires comprehensive beneficiary protections and avenues for recourse, sound payment rates, adequate provider networks and access to care, and data reporting by plans and states.

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw substantial growth in Medicaid managed care enrollment as states sought to accommodate growing Medicaid enrollment during a time of fiscal pressures. In this period, states were more concerned with managing costs than managing care. Over time, managed care has grown as states have expanded their programs to include wider geographic areas and additional beneficiary groups and shifted from voluntary to mandatory enrollment models.5 6 7 As of 2015, 38 states and DC have risk-contracting programs, and more than half of all Medicaid beneficiaries nationally are enrolled in comprehensive managed care plans, many on a mandatory basis.

Historically, states largely limited managed care to pregnant women, children, and parents, but they are increasingly including Medicaid beneficiaries with complex needs, including persons with disabilities and elderly enrollees. People who use the most services can experience the most fragmentation, gaps, and redundancies in care and can potentially benefit most from managed care. However, they are also the most exposed to the risk of underservice inherent in capitated systems and may have difficulty navigating managed care and gaining access to needed providers and services. State experience covering higher-need populations through managed care is generally limited and most managed care plans have not typically served them. Thus, the adequacy of provider networks and plan capabilities to handle more complex care needs, and rigorous state and federal oversight of access and quality, are crucial issues as Medicaid programs move in this direction. Medicaid managed care programs and oversight vary widely from state to state, and evidence about the impact of managed care on access to care and costs is both limited and mixed.8 9 10 11 The continued expansion of managed care in Medicaid despite the absence of systematic evidence that it improves access or lowers costs is a serious concern, deepened by the lack of managed care data, analysis, and oversight at the federal level.12, 13 After more than a decade, CMS is developing new Medicaid managed care regulations.14 The new rules could strengthen current requirements on states and plans, but ultimately their traction will hinge on effective state and federal enforcement.

Medical homes, health homes, and integration of services

While risk-based managed care dominates the Medicaid delivery system reform landscape, not all states contract with plans, and other innovative and complementary strategies designed to improve care are prevalent in the program. At least half the states have implemented primary care medical homes and pay fee-for-service providers an extra monthly amount to coordinate and monitor primary care services (and sometimes provide additional services for their Medicaid patients). Primary care medical homes may also be implemented in the context of managed care plans.15 Other state approaches build on the medical home model but involve coordination across a broader spectrum of services. Medicaid “health homes” operating in more than a dozen states coordinate physical, behavioral, and long-term care, as well as family supports and social services, for beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions or a serious mental illness.16 Improving the coordination and quality of care for these high-need, high-cost beneficiaries is a major focus of federal and state delivery system innovation efforts in Medicaid (as well as other public programs). These efforts aim to address the fragmentation of care as well as reduce Medicaid costs through lower rates of preventable hospital and nursing home care.

Many Medicaid beneficiaries have comorbid physical and behavioral health conditions and improving the management of their care has been a focal area of delivery system reform activity. In recent years, a majority of states have undertaken initiatives to integrate physical and behavioral health services.17 One innovative approach that several states have implemented is to designate community mental health centers and other mental health entities as Medicaid health homes for beneficiaries with mental illness, based on an assessment that these providers have the appropriate expertise and are in the best position to coordinate services and supports for this population. In the managed care environment, many states are now integrating behavioral health services previously “carved out” from plans into their comprehensive risk-based contracts to promote more holistic care and consolidate accountability.

Long-term services and supports

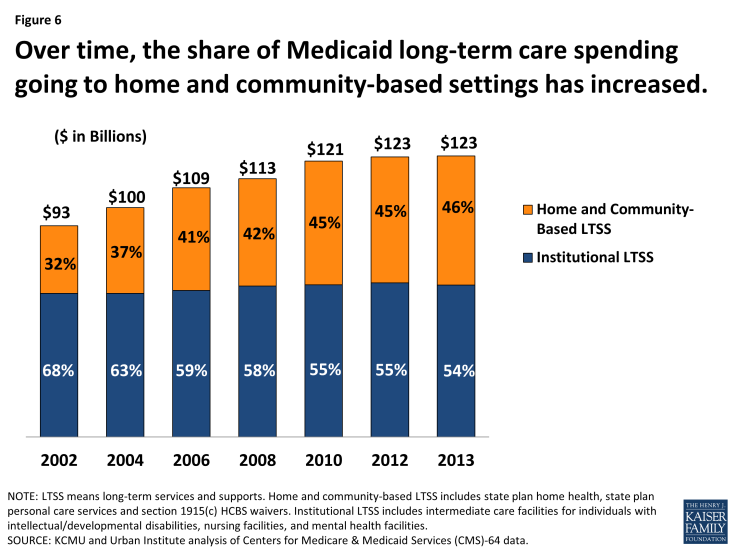

Medicaid’s contribution to delivery system transformation is nowhere more significant than in the long-term care arena. As the principal source of coverage and payment for long-term services for Americans, the Medicaid program has essentially shaped the delivery system. Medicaid financing is essential to the nation’s nursing homes. At the same time, the program has facilitated the dramatic expansion of access to home and community-based long-term services and supports as states have invested and shifted more long-term care spending to non-institutional settings.18 By 2013, 46% of all Medicaid long-term care spending was for home and community-based services, compared to 32% in 2002 (Figure 6). These services underpin independent living and community integration of individuals with disabilities and the elderly.

Figure 6: Over time, the share of Medicaid long-term care spending going to home and community-based settings has increased.

A developing branch of innovation is the delivery of long-term care benefits through managed care arrangements. Under CMS-approved waivers, about 20 states are now operating managed long-term services and supports programs, generally statewide, and nearly all of these states require nonelderly adults with physical disabilities and seniors to enroll in managed care to receive services.19 Most of the programs provide for comprehensive Medicaid benefits, including acute care and behavioral health services as well as nursing facility and home and community-based care, breaking new ground in efforts to more fully integrate care for individuals with long-term needs. But the extensive needs and special vulnerabilities of the beneficiaries involved, and the unfamiliar terrain of managed care for most, raise new concerns and call for strong beneficiary supports and protections, such as assistance choosing plans and measures to maximize continuity of care during the transition to managed care. Managed care plans new to providing long-term services and supports, and long-term providers new to managed care, have a challenging learning curve to climb.

Probably the most challenging and ambitious innovation projects in Medicaid are the state demonstrations proceeding under the ACA initiative to align Medicare and Medicaid financing and coordinate service delivery for dual eligible enrollees. All but two of the 11 states currently slated to move ahead with financial alignment demonstrations rely on capitated managed care plans to coordinate the full complement of Medicare and Medicaid services.20 These demonstrations hold potential to enhance the quality and cost-effectiveness of the care that dual eligible beneficiaries receive. However, uneven levels of state experience serving dual eligible enrollees through managed care, uneven levels of plan experience in the Medicaid and Medicare markets, especially with long-term services and supports, and variable plan quality highlight significant issues surrounding the implementation of these reforms for this very poor and uniquely frail population.21

Quality performance

Since its early years, Medicaid has evolved in many states from a passive claims payment program to a more active purchaser that uses its leverage to drive improvements in the quality of care provided to beneficiaries and to foster more accountable systems of care. This evolution has proceeded via diverse mechanisms, including managed care, the development and state use of quality metrics in Medicaid, and integrated delivery systems and innovative payment approaches that reward providers for high quality performance.22 Quality improvement in the nation’s public health coverage programs is also a major federal priority and focus of increased investment. However, the Medicaid quality enterprise is very much a work in progress. Not all states are engaged. State-level technical, analytic, and financial capacity and resources to pursue quality initiatives are limited and there are many competing priorities both within and outside Medicaid. It bears noting that the development of metrics to assess the quality of care received by people with disabilities is in its infancy. Measures to assess and monitor access and outcomes across settings in managed long-term care programs are needed as well.23

Medicaid’s Role in Health Care Financing

As the health coverage program for more than 1 in 5 nonelderly Americans and the main payer for long-term care, Medicaid is a core source of financing in our health care system. It plays an especially large financing role in certain domains. The program provides substantial financing for the health care safety-net – Medicaid payments account for 35% of safety-net hospitals’ revenues and 40% of health center revenues.1 2 Medicaid also finances one-quarter of all behavioral health care spending nationally.3 The program pays for nearly half of all births in the U.S. and plays a singular role in financing health care for women and children. Medicaid also pays half the national bill for long-term services and supports needed by people with disabilities and the elderly. Overall, Medicaid finances $1 of every $6 of personal health spending nationally.

The lion’s share of Medicaid spending – nearly two-thirds – is attributable to people with disabilities (42%) and elderly beneficiaries (21%), although they make up just one-quarter of all Medicaid enrollees. Dual eligible enrollees make up 14% of all beneficiaries, but these nearly 10 million seniors and people with disabilities drive 40% of all Medicaid spending. As these figures help to illustrate, Medicaid is an expensive program because it finances the high per-enrollee costs of care for many Americans with the most extensive needs for health care and long-term care services. For other populations, such as children and nondisabled adults, Medicaid provides coverage at a low per-enrollee cost relative to other payers.4 Growth in aggregate Medicaid spending over time is driven primarily by increasing enrollment in the program due to coverage expansions, demographic trends, and economic conditions. On a per-enrollee basis, however, Medicaid spending has been growing more slowly than private insurance premiums and national health spending per capita.5

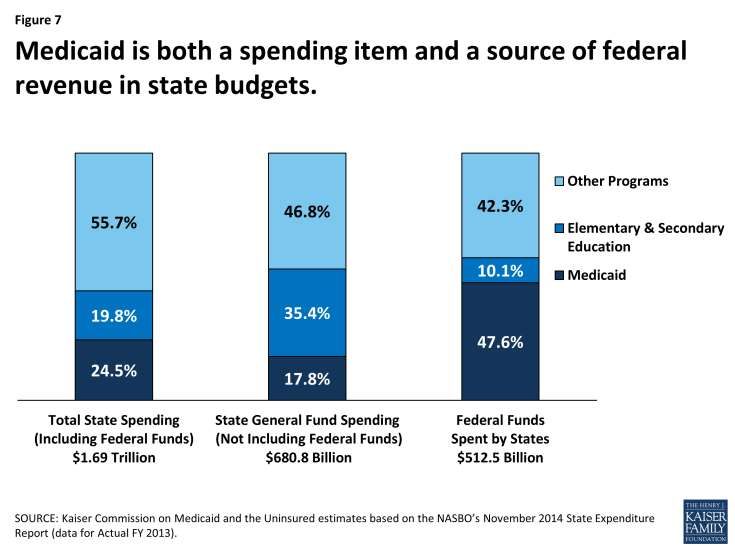

Under the federal-state Medicaid partnership, the federal government matches state Medicaid spending. Thus, Medicaid is a source of both spending and revenue for states (Figure 7). Indeed, the program is the largest source of federal funds flowing to states. The federal match rate for state Medicaid spending associated with enrollees who are eligible under pre-ACA rules ranges from a floor of 50% to 74% in the poorest state, and the federal share of Medicaid spending overall is 57%.6 However, the federal government pays almost the full cost of the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income nonelderly adults (100% through 2016 and phasing down to 90% thereafter). This and other enhanced matching rates for certain other populations under the ACA will increase the average federal share for Medicaid in the next 10 years to between 62% and 64%, depending on the year.7

By federal law, the federal government also matches state spending for “DSH” payments, supplemental payments to hospitals known as disproportionate share hospitals because they serve large numbers of Medicaid and uninsured patients. Federal matching payments for DSH are capped and each state receives an allotment. Beyond minimum federal standards, states have considerable discretion to define hospitals that qualify for DSH payments and to allocate DSH dollars among them. For many safety-net hospitals, Medicaid DSH payments are a critical stream of operating revenues that help subsidize the substantial uncompensated care these institutions provide to uninsured and underinsured people. The ACA called for reduced federal DSH allotments beginning in 2014 corresponding with anticipated increases in coverage and reductions in uncompensated care costs under the new law, and the ACA also called for targeting of the reductions to better achieve the purposes of DSH payments. Due to concerns about potential funding issues for safety-net hospitals that have relied heavily on DSH funds, Congress has delayed implementation of the DSH cuts until FY 2018.

Access to federal Medicaid matching funds has helped to spur state expansions of health coverage for their uninsured residents. It has also provided support for state actions like raising provider payment rates and adding new benefits and helped states with higher Medicaid costs stemming from medical inflation. Federal matching funds have also enabled states to free up their own revenues by, for example, shifting mental health spending previously financed with state-only funds into Medicaid. In addition, because federal funding for Medicaid is available as needed, Medicaid can expand as a safety-net when economic downturns, epidemics, or disasters such as 9/11 or Hurricane Katrina create new needs for coverage. As responsive as this structure is, though, it does not accommodate heightened state fiscal pressures that occur when the local or national economy contracts, leading to increased Medicaid enrollment just when state revenues are declining. Struggling with recessionary budget pressures, states have frequently sought to constrain Medicaid spending by cutting benefits or provider payment rates. Many have made the case that the matching system needs an adjustment to deal with this countercyclical dynamic. Twice, in hard economic periods, Congress has raised the federal match rate to provide additional support to states.

Regardless of the prevailing budget environment, Medicaid spending and financing issues have always produced pressures and tension between the federal government and the states. Although state spending and cost-containment pressures are most acute during economic downturns, rising Medicaid spending is a standing issue for states because they pay a significant share of program costs and must balance their budgets every year. At times, states have sought to maximize federal Medicaid funds in ways not intended by Congress to artificially inflate the federal share of Medicaid spending, sometimes using legal financing mechanisms, including DSH payments, provider taxes as a source of state Medicaid funds, and intergovernmental transfers. Such state practices, which erode the integrity of the matching structure, have fueled concerns about open-ended federal matching funds and the impact on federal Medicaid spending, and led Congress to pass a series of laws clamping down on inappropriate state uses of federal funds.

More fundamental debate about the very structure of Medicaid financing has flared periodically, often within the larger frame of federal deficit reduction discussions. Some policy makers have proposed to convert Medicaid from an entitlement with guaranteed federal matching dollars to a block grant program with caps on federal funding and increased state flexibility to decide who and what to cover. Several analyses that have modeled the potential impact of these approaches indicate that they could shift substantial costs to states, beneficiaries, or providers, and/or lead to reductions in coverage or benefits, but the debate over federal versus state financing and how to contain costs for both the federal and state governments is ongoing.8,9

Looking Forward

Over its 50-year history, the Medicaid program has evolved to fill extensive gaps in our health care system, demonstrating remarkable versatility and effectiveness. But its evolution, far from smooth, has been punctuated by controversy and debate regarding who and what Medicaid should cover, who should pay, how Medicaid services should be delivered, Medicaid’s size and impact on state and federal budgets, and even its basic structure. Federal-state tensions are part and parcel of the Medicaid partnership under which states have broad flexibility to design their programs subject to federal minimum requirements and the federal government guarantees matching funds for their Medicaid spending. This compact is at the heart of the Medicaid program’s adaptability to needs and preferences that vary from state to state, and it has catalyzed significant state coverage expansions and flourishing innovation in the design of Medicaid benefits, service delivery, and payment systems. At the same time, also because of this compact, low-income Americans’ access to coverage and care depends on the state they live in and millions remain uninsured, raising major concerns about equity and exposing important costs of federalism.

As this report illustrates, notwithstanding perennial debates about Medicaid’s role, the program has been the principal vehicle of both federal and state efforts to cover the uninsured, transforming gradually from its origins as a small health care safety-net limited to those receiving welfare, into a core provider of health coverage in the U.S. today. Because of Medicaid, low-income pregnant women have access to prenatal care and their babies get a healthy start. Low-income children get recommended immunizations and other preventive and primary care. New research shows that these early benefits also yield longer-run returns in the form of higher educational attainment, earnings, and tax revenues and lower use of other public assistance. Medicaid is also the main coverage program for a large share of Americans with disabilities, many of whom need long-term services and supports for which there is no adequate private insurance alternative. And without Medicaid, it is unclear what the fate of millions of seniors unable to afford Medicare premiums or the staggering costs of long-term care would be. Separate from these standing coverage roles, Medicaid also serves as an adaptable coverage safety net during recessionary periods and public health challenges like HIV/AIDS, mitigating their harmful human and economic consequences.

By covering many of the poorest and frailest people in our society and providing comprehensive benefits, Medicaid also buttresses the other key pillars of our health insurance system. It supports and fills in gaps in private insurance and provides billions of dollars of premium payments to private insurance companies with Medicaid managed care contracts. And it shores up the Medicare program by covering nursing home care and other long-term care for elderly low- and middle-income Americans. The program also provides significant financing for providers and the health care delivery system. In particular, Medicaid payments provide core support for safety-net hospitals and health centers, the nation’s children’s hospitals, and the mental health system, and Medicaid is the major source of revenue for nursing homes and providers of home and community-based services. Medicaid coverage and financing have also been the levers of far-reaching innovation in the delivery of both health and long-term care, as states have used their programmatic flexibility and purchasing power to pioneer new models of care and payment designed to improve quality and lower costs for populations whose complex and expensive needs are a major driver of health care spending in Medicaid and system-wide.

Finally, Medicaid has large impacts on state economies. Federal Medicaid matching payments represent a large infusion of federal revenues into states and over half of all Medicaid spending. A substantial body of studies shows that these Medicaid revenues can have a stimulative effect in states.1 2 3 Namely, as states spend on Medicaid and draw down federal matching funds, the spending filters through state economies, providing increased revenues to providers, including hospitals, private physicians, health plans, nursing homes, and vendors, and, in turn, generating increased employment and productivity both within and outside the health care sector, higher earnings and household spending, and additional state and local tax revenues. Nonetheless, the high cost of the Medicaid program is a lightning rod in the context of competing priorities and balanced-budget requirements at the state level, and in the context of deficit reduction debates and deeper ideological divides at the federal level.

In considering the future of the Medicaid program, five key issues that are likely to be formative and that could play out in different ways stand out. How the debates surrounding these issues are settled will have significant implications for the Medicaid program itself and also for its impact on low-income Americans and on our health care system.

Coverage

Inequities and gaps in Medicaid coverage due to state flexibility are woven into the fabric of the Medicaid program. However, Congress’ expansions of Medicaid over time to cover uninsured Americans nationally, beginning with children, reveal evolving views regarding the boundaries of acceptable variation in coverage under the program. The ACA represents the fullest expression of this evolution. While substantially preserving other domains of state flexibility in Medicaid, the law fundamentally recast Medicaid as a national program from a coverage standpoint both by establishing a uniform national eligibility floor for nonelderly Americans regardless of where they live and by providing for nearly full federal funding of the expansion. The June 2012 Supreme Court decision, which effectively permitted states to opt out of the Medicaid expansion, might be considered the latest manifestation of the federal-state push-and-pull that has always attended Medicaid. The ruling’s disproportionate impact on access to coverage for people of color and residents of the South vividly illustrates how state flexibility in Medicaid, which can be an instrument of innovation and progress, can also hold back efforts to eliminate health and social disparities.

At this writing, the ACA Medicaid expansion has been adopted by more than half the states and millions of low-income Americans have gained coverage as a result. However, the states that have so far not adopted the expansion have left almost 4 million poor uninsured parents and childless adults without access to affordable coverage. What these states ultimately decide about the Medicaid expansion will determine whether the ACA’s vision of Medicaid as the universal program for people with low income is fully realized or, instead, the very gaps in coverage targeted by the health reform law are allowed to persist. Between Summer 2013, just prior to the first ACA open enrollment period, and January 2015, there was a net increase in Medicaid and CHIP enrollment of nearly 11.2 million individuals.4 Numerous factors besides state Medicaid expansion decisions influence Medicaid enrollment growth, including demographics, economic conditions, and take-up rates. But it is notable that enrollment growth was over three times greater in states that implemented the Medicaid expansion than in states where the expansion was not in effect (26% vs. 8%).

Adequate Financing

States’ open-ended access to federal Medicaid matching dollars has undergirded the Medicaid program’s capacity to respond as needs change due to economic vicissitudes and demographic trends, as new technologies emerge and health care costs rise, and as states move in new policy directions. The matching arrangement also gives the federal government and states common stakes in the fiscal management of Medicaid and high program performance. Still, the lack of an automatic adjustment to deal with countercyclical pressures on states remains an important challenge in Medicaid. On two occasions, during the recessions in 2001 and the late 2000s, Congress temporarily increased the federal match rate to provide fiscal relief to the states. Building a permanent mechanism that responds to recessionary pressures into the funding formula to support states could strengthen the Medicaid program.

Proposals to convert Medicaid from an entitlement to states and individuals to a federal block grant program have emerged periodically over the last 20 years and continue to be part of ongoing discussions about financing Medicaid in the future. At the heart of this debate is controversy about the appropriate level of federal financial commitment to Medicaid and whether federal funding should be capped, and about how much discretion states should have over program design. Advocates of a Medicaid restructuring that would involve capped federal funds and reduced federal requirements on eligibility and benefits believe that this approach would help to control federal spending while giving states additional levers to manage within federal funding constraints. However, others raise concerns that limiting federal funding for states would constrain Medicaid’s ability to respond to changing needs and could lock in existing differentials among states. They also argue that, if federal support were diminished, states might scale back Medicaid eligibility, benefits, and provider payment rates, jeopardizing access to coverage and care.

As implementation of the ACA proceeds, continued analysis of the fiscal implications of states’ Medicaid expansion decisions will be important. In the coming years, substantial federal funds will flow into states that expand Medicaid, with relatively small state costs. Based on evidence from earlier studies, the new funds associated with the Medicaid expansion are anticipated to have a noticeable and sustained positive impact on state economic activity.5 The high federal match under the ACA increases the economic returns of Medicaid to state economies, and states that have not adopted the Medicaid expansion, in addition to leaving millions uninsured, are leaving billions of federal dollars on the table. There is also early evidence that state Medicaid expansion decisions have substantial impacts on providers, with a recent study showing that hospitals in Medicaid expansion states saw both greater increases in Medicaid patients and decreases in uninsured patients, and much larger reductions in charity care costs, compared to hospitals in non-expansion states.6

Flexibility