A Look at the Private Option in Arkansas

Key Findings

Interviews with stakeholders and early data reveal the impact of the private option’s early implementation in the following areas:

Coverage

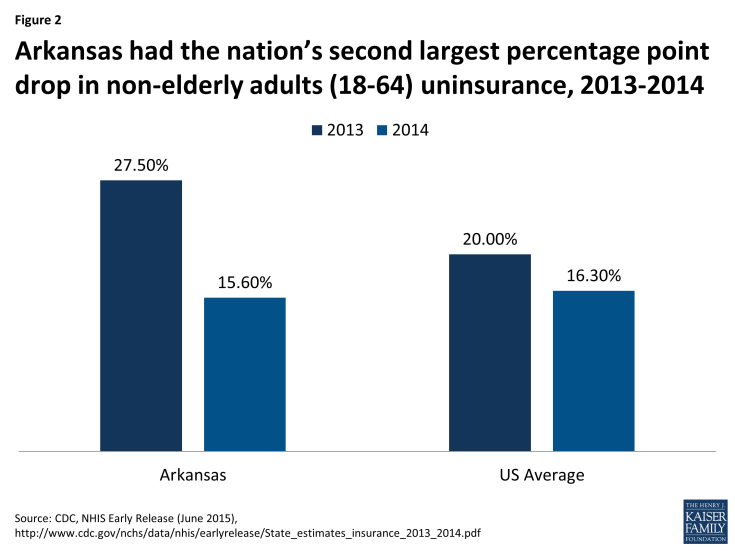

Since the private option’s launch in October 2013, 245,000 people1 have enrolled in coverage, contributing to Arkansas’s role as a national leader in reducing the uninsured rate. Between 2013 and 2014, Arkansas cut its uninsured rate among non-elderly adults almost in half, dropping it from 27.5 percent to 15.6 percent, one of the largest declines in the country (Figure 2).2 States that adopted a traditional Medicaid expansion also experienced sizeable reductions in uninsured rates.3 Advocates, providers and others report that the coverage has been “a blessing” for Arkansans, many of whom never had coverage before and who previously got care only episodically or in emergencies, leaving them with untreated chronic conditions and without reliable access to preventive care. The private option expansion also is credited with reducing the incentive to apply for SSI benefits by making health coverage available and helping people get medical treatment so they can return to work; since the private option expansion was implemented, SSI applications in Arkansas have dropped for the first time, by about 19 percent.4

Figure 2: Arkansas had the nation’s second largest percentage point drop in non-elderly adults (18-64) uninsurance, 2013-2014

The private option expansion is not the only source of coverage gains in Arkansas, but it has contributed substantially to the reduction in Arkansas’s uninsured. The state also has some 54,000 people enrolled in Marketplace plans outside of the private option,5 as well as an increase in enrollment in its pre-existing Medicaid program. As some stakeholders pointed out, the extent of these coverage gains reflects in part that Arkansas had one of the highest uninsured rates in the country prior to implementation, magnifying the importance of the state’s decision to establish the private option. Prior to expanding Medicaid, Arkansas covered parents with incomes below 17 percent FPL ($3,415 per year for a family of three in 2015), one of the lowest eligibility thresholds in the country.6 It did not provide any coverage for childless adults without disabilities regardless of how low their income was.

Outreach and Enrollment

As the private option expansion was first being implemented in the fall of 2014, the state was able to quickly and efficiently enroll 60,0007 eligible individuals using “fast track” enrollment strategies offered by CMS. Under fast track enrollment, the state Medicaid agency used data available from SNAP files to identify parents and childless adults who met the private option eligibility criteria and sent them an enrollment form to return if they wanted coverage. By using data it already possessed, Arkansas generated a one-time boost in enrollment that contributed to a strong launch of the private option. Stakeholders also cited the state’s rapid creation of the enrollment portal that allows individuals eligible for the private option to select a Marketplace plan as contributing to the initial enrollment success.8 However, some interviewees noted that the fact that there are two separate web portals for eligibility determinations and plan selection increases the complexity and administrative burden of the enrollment process for beneficiaries; one stakeholder also noted that even if there was a single portal for eligibility and plan selection, beneficiaries still might feel overwhelmed or confused by the plan choices and not select a plan on their own.

Many stakeholders felt the legislature’s 2014 decision to bar the use of government funding for outreach and enrollment negatively affected beneficiaries. Hospitals, community health centers and advocacy groups stepped in to provide some education and outreach and partnered with churches and local businesses with connections to beneficiaries, such as the poultry industry, to provide enrollment assistance, but they have not been able to fully meet this need. Stakeholders reported that beneficiaries are sometimes confused about their health plan options, where to go for help if they have issues, and which government agency – the state Medicaid agency or state insurance department – is responsible for answering their questions.9 One concern is that the ban on state expenditures for outreach may contribute to a higher-than-necessary rate of auto-assignment into Marketplace plans; lacking sufficient assistance, some beneficiaries may be auto-assigned to a plan and therefore miss the opportunity to complete the medically frail screening process and select a health plan as discussed below.

A number of stakeholders pointed out that the issues confronting Arkansas’s Medicaid eligibility and enrollment system have added to the challenges beneficiaries face in navigating the private option. Like a number of other states, Arkansas has faced challenges complying with the sweeping changes made to Medicaid eligibility and enrollment procedures in the ACA. These larger system issues are not specific to the private option, but they still have resulted in enrollment delays, added to beneficiary confusion, and raised concerns about the timeliness of coverage renewals.

Medically Frail Enrollees

Stakeholders thought the medically frail screening tool worked well to identify people with extensive health care needs who would be better served in the traditional Medicaid program. No one reported hearing about beneficiaries who wanted to be considered medically frail but who could not secure this designation. As of June 2015, 9.95 percent of newly eligible adults – or 25,800 individuals – were deemed medically frail and enrolled in the state’s fee-for-service Medicaid program.10 By default, they receive the traditional Medicaid state plan benefit package, which includes long-term services and supports (LTSS) not available to private option enrollees. At their option, medically frail individuals instead can elect to receive the same benefit package as private option enrollees (although they still receive these benefits through the fee-for-service system). In some instances, the private option benefit package may be more useful to a beneficiary depending on individual circumstances; for example, it includes substance abuse treatment services not available in Arkansas’s traditional Medicaid benefit package for adults. To date, the vast majority – 88 percent – of those designated medically frail have remained in the traditional Medicaid benefit package.11 Additional information about Arkansas’ medically frail screening process is contained in the box on the next page.

| Arkansas’ Medical Frailty Screening Tool |

| Once determined eligible for Medicaid, newly eligible adults in Arkansas are instructed to visit the state enrollment portal to complete a 12-question screening tool to assess whether they qualify as “medically frail.” The screening tool is designed to identify people with extensive medical needs, such as those with serious and complex medical conditions, disabling mental health disorders, and limitations with one or more activities of daily living. The screening tool includes the following domains: health self-assessment; living situation; assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs); overnight hospital stays (both acute and psychiatric); and number of physician, physician extender or mental health professional visits. It gathers information online (unless an individual requests a paper copy) and consists of yes/no and multiple choice questions. Responses are entered into software that calculates whether the person meets the medically frail criteria. The screening tool methodology is a combination of threshold qualifying characteristics, such as the presence of an ADL or IADL limitation, and a weighted scoring algorithm based on applicant responses to other screening questions.

As of February 2014, out of 105,000 beneficiaries eligible for the private option, 58,000 bypassed the medical frailty screening, 36,000 were screening and determined not to be medically frail, and 11,000 were screened and determined to qualify as medically frail.12 Of these 11,000 medically frail beneficiaries, 3,000 were automatically deemed medically frail because they have an ADL or IADL limitation; are homeless or living in an institution or group home; or have a history of psychiatric hospital admissions.13 The remaining 8,000 medically frail beneficiaries qualified because they were determined likely to need services placing them in the top 10 percent of costs, based on their self-reported health status, inpatient admissions, and emergency room and office visits for physical and mental health conditions in the last six months.14 |

Stakeholders expressed concern that some individuals are bypassing the medically frail screening because they are auto-enrolled into plans. As of June 2015, 40 percent of individuals identified as newly eligible in year 2 of the program were auto-enrolled into plans.15 Because they did not go to the enrollment portal to select a Marketplace plan, they also missed the chance to complete the medically frail screening. Beneficiaries who bypassed the medically frail screening included those who were automatically enrolled based on SNAP data and those who applied for coverage on the federal Healthcare.gov website. Despite the large number of enrollees who bypassed the screening tool, Arkansas met its estimate of identifying 10 percent of newly eligible adults as medically frail because 23 percent of those who responded to the screening tool between October 2013 and February 2014 qualified.16

While they can elect to undergo medically frail screening at any time, it is not clear that beneficiaries are always aware of this option. Moreover, the mid-year process that insurance carriers use to identify medically frail individuals is a source of confusion and is used sparingly. To date, only about 18 additional individuals have been identified as medically frail after carriers flagged them for screening based on their claims history.17 Of these, 5 enrollees asked to be moved to fee-for-service Medicaid. The remainder elected to remain with their Marketplace plans raising the prospect that at least some medically frail individuals may prefer enrollment in Marketplace plans if they are not in need of the specialized services available in the traditional Medicaid package.18 The state is including a reminder in the renewal notices sent to people who must take action to continue their coverage that they should return to the enrollment portal to select a plan and, in the process, undergo screening for medical frailty.19 Beneficiaries also have the opportunity during the open enrollment period to select a new plan and, if they do, they will be prompted to undertake a medical frailty screening.20

Arkansas designed its medical frailty screening tool not only to identify those with exceptional needs, but also to minimize the risk that plans would have to cover beneficiaries with the highest costs in the first year of the private option. Arkansas targeted the group of beneficiaries who are expected to incur the top 10 percent of health care costs as a proxy for identifying those who were most likely to need services, such as LTSS, that are not available in the Marketplace plans’ benefit package.21 State officials reported that insurers needed information about the private option risk pool to establish Marketplace premiums in the first year, and the 10 percent target helped provide predictability for this purpose.22 State officials also indicated that the medically frail screening tool was designed to be over rather than under-inclusive initially, by targeting people with “exceptional medical needs” in addition to those who meet the federal definition of medically frail.23 In future years, the state expects to refine the screening tool to eliminate false positives, validate screening responses through claims data, and better identify beneficiaries who need LTSS.24 To date, medically frail beneficiaries (10 percent of newly eligible adults in Arkansas) account for about 17 percent of expenditures for Arkansas’ entire Medicaid expansion population.25

Stakeholders highlighted the importance of continuing to improve the state’s Medicaid fee-for-service delivery system for medically frail individuals. Medically frail individuals, by definition, are likely to have more extensive health care needs and higher costs than other newly eligible adults. A number of stakeholders pointed out that medically frail enrollees are perhaps in greater need of better provider networks and delivery systems than private option enrollees. Given that Marketplace plans may not be well-equipped to provide some of the more specialized long-term services and supports critical to many individuals who are medically frail, stakeholders did not recommend that this population be mandatorily enrolled in the private option, but rather that steps be taken to strengthen the fee-for-service delivery system available to such individuals or perhaps that they be given the choice of enrolling in the private option when that system could better meet their individual needs.

Access to Care and Utilization

One of the clearest themes to emerge from interviews with stakeholders was that the private option coverage expansion has succeeded in providing beneficiaries, most of whom were previously uninsured, with access to care.26 States that implemented traditional Medicaid expansions also saw significant gains in access to care among adults who gained coverage.27 Stakeholders reported that beneficiaries appreciate having the same commercial insurance card as other Marketplace enrollees and the access to doctors, hospitals, clinics, and specialists that these plans offer. The access to specialists was highlighted by a number of stakeholders as particularly important: while traditional Medicaid beneficiaries often can secure primary and preventive care from community health centers, they may encounter more challenges accessing specialists. An additional advantage of consistent access to care is that it allows private option enrollees to receive care coordination and monitoring of their conditions over time. In the past, many private option enrollees were largely excluded from the health care system – they might have had intermittent care, but they did not have access to continuous coverage. On the other hand, one stakeholder suggested that a lack of experience with commercial insurance plans might have resulted in underutilization of benefits by private option enrollees.

The private option expansion also may be increasing access to care for all Arkansans. In some instances, the private option is credited with encouraging carriers to develop capacity that generated a positive spill-over effect for all community members. One stakeholder, for example, cited a carrier’s decision to set up new outpatient clinics as an outgrowth of the private option coverage expansion. Another noted that some clinics and providers throughout the state are now offering Saturday hours to accommodate the growth in the number of insured patients. This expansion of access may also be related to the state’s patient-centered medical home initiative, which also was included in the legislation that created the private option. It is one component of a larger multi-payer comprehensive payment reform effort aimed at incentivizing quality and cost-effective care delivery in which marketplace plans are required to participate.

Providers

The Arkansas Hospital Association (AHA) reports that hospitals are experiencing a dramatic drop in uninsured patients and uncompensated care costs. In addition, the AHA survey data also point to patients possibly seeking care in community-based settings instead of emergency rooms, with 5.8 percent growth in use of hospital outpatient clinics during the first six months of 2014.28 On the other hand, insurance carriers report relatively high rates of emergency room visits by private option enrollees, suggesting that private option enrollees may still be learning how best to use their coverage.29 More clear is that hospitals are experiencing drops in uninsured patients and uncompensated care costs. In 2014, inpatient visits by uninsured patients dropped 48.7 percent, uninsured emergency room visits by 38.8 percent, and uninsured outpatient clinic visits by 45.7 percent (compared to 2013).30 Hospitals also experienced corresponding gains in financial stability, with uncompensated care losses related to uninsured patients falling by 55.1 percent, or $149 million, from 2013 to 2014. 31 States that adopted a traditional Medicaid expansion also experienced sizeable decreases in uncompensated care costs as more of the uninsured gained coverage.32

The private option expansion’s impact on Arkansas community health centers is more mixed and varied across the state. Community health center leadership is enthusiastic about the coverage expansion, and centers are actively helping people enroll in coverage, using funds provided by the federal Department of Health and Human Services. Moreover, centers, particularly those in isolated rural areas, are seeing positive impacts from the expansion as more of their patients gain coverage and they receive more revenue as a result. Some community health centers, however, have been surprised to continue to see large numbers of uninsured patients. The reasons are not entirely clear but could include that these patients do not meet Medicaid’s immigration and citizenship eligibility criteria; the enrollment process is challenging for people with language and other barriers to navigate; and/or their applications are caught up in the state’s eligibility system delays. Of particular concern to many community health centers is that, as of April 2015, the state had not yet fully implemented the system for ensuring that centers receive cost-based reimbursement for private option enrollees.33 As a result, while community health centers are seeing new revenue as more of their patients gaining coverage, they are not necessarily experiencing the full gains in financial stability they had expected. In addition, some community health centers are concerned that they will lose newly-insured patients to other providers, including some of the new clinics being established by Marketplace plans, and that they could be left with a greater concentration of uninsured patients.

Premiums, Cost-Sharing and Health Independence Accounts

Unlike traditional Medicaid premium assistance programs, a major innovation of the private option is that beneficiaries are fully protected from cost-sharing charges without requiring them to pay upfront and be reimbursed. Stakeholders said that the system for the state Medicaid agency’s payment of premiums directly to Marketplace plans worked smoothly.34 In addition, by combining a standardized cost-sharing design with supplemental cost-sharing reduction payments directly to Marketplace plans, Arkansas ensures that private option enrollees do not incur cost-sharing charges for which they are not responsible.35 The cost-sharing reduction payments represent a little more than a quarter (27.4 percent36) of the payments made to Marketplace plans on behalf of private option enrollees, although this share is expected to shift when these payments are reconciled based on actual utilization.37 An estimated 81 percent of private option enrollees have income below 100 percent FPL and therefore are enrolled in a 100 percent actuarial value plan with the state paying all of the plan’s required cost-sharing.38 Beneficiaries from 100-138 percent FPL are enrolled in 94 percent actuarial value plans and have some co-payments for services consistent with Medicaid standards.

It is too early to assess the impact of Arkansas’s new Health Independence Accounts. In 2014, Arkansas added Health Independence Accounts to the private option, which had been called for by the original legislation creating the initiative. It did so with the goal of promoting personal responsibility and creating greater similarities with the cost-sharing charges people face as they move into other forms of coverage.39 Beneficiaries are expected to make a monthly contribution of $10 or $15 (depending upon income) to their accounts and are provided with a debit card than can be used to cover their co-payments and co-insurance when they use services.40 As of July 2015, 45,839 account cards have been issued, 10,806 cards have been activated, and 5,185 beneficiaries had contributed to their accounts.41 At the time of the interviews, Arkansas was in the midst of implementing these accounts for individuals above 100 percent of the federal poverty level. Since only about 20 percent of private option enrollees are in this income range, and the program is new, most stakeholders had little or no direct experience with the functioning of these accounts. Hospitals had received training on how the accounts would work so that they could respond to beneficiary questions. Some stakeholders felt that the accounts would be confusing to beneficiaries and complex to administer, particularly given that limited resources are available to educate beneficiaries about how the accounts work. Others viewed them as an important means of providing beneficiaries with incentives to more actively manage their health insurance. The state did not implement the accounts for individuals below 100 percent of the FPL after considering a number of factors, including the administrative expense of the accounts and the size of the contributions that would be made by individuals in this income range.

Benefits

Stakeholders said that beneficiaries generally reported being well-satisfied with their coverage through Marketplace plans.42 The private option benefit package is based on the ten essential health benefits required by the Affordable Care Act, which includes services such as hospital care, lab and x-ray services, and primary and preventive care, among others. The package also includes mental health and substance abuse services, which are not covered to the same degree in Arkansas’ traditional Medicaid benefit package for adults. Early on, some private option enrollees selected and received premium subsidies for Marketplace plans that included some dental and vision benefits. These services are not covered for newly eligible adults in Arkansas, and the state Medicaid agency ceased paying premiums for those plans. These services, however, had been very popular, and beneficiaries were disappointed when they were eliminated.

Arkansas minimized the need for the state to provide required Medicaid benefits outside of Marketplace plans, but beneficiaries may not be clear about how to access the limited services provided through a wrap. By design, there is almost complete overlap between the benefits covered by Marketplace plans and the Medicaid benefits required for newly eligible adults. Consequently, the state offers private option enrollees only two benefits outside of the Marketplace plan: non-emergency medical transportation and EPSDT benefits for 19 and 20-year olds. Stakeholders reported that the state had given providers information about how to assess wrapped benefits so they were able to assist beneficiaries, but they were less confident that beneficiaries would be able to navigate this issue on their own. One interviewee posited that beneficiaries using wrapped benefits most likely did so after learning about them through providers or word of mouth. Some expressed particular concern that 19 and 20-year olds are not necessarily aware of their eligibility for EPSDT benefits, although they had not heard of problems directly from beneficiaries, perhaps because young adults with serious health care needs are more likely to be classified as medically frail and to receive all of their benefits through the fee-for-service system. Finally, stakeholders flagged that the state has had some issues with its non-emergency medical transportation benefit, such as confusion among beneficiaries about how to access the benefit, but they also pointed out that these challenges are not a function of the private option but rather affect all Medicaid beneficiaries in Arkansas.

Marketplace enrollment and plan options

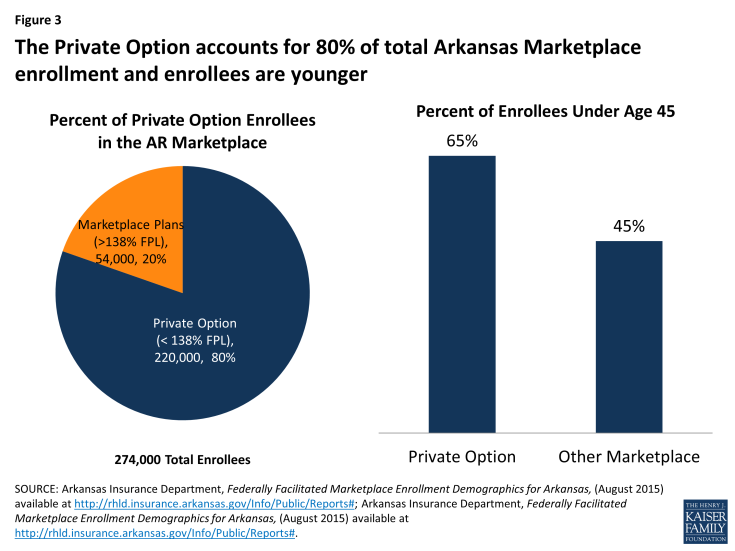

The private option has had a positive effect on the Arkansas Marketplace. When submitting its waiver request for the private option, Arkansas posited that “by nearly doubling the size of the population enrolling in QHPs offered through the Marketplace,” the demonstration would “drive more competitive premium pricing for all individuals purchasing coverage through the Marketplace.”43 The private option has exceeded expectations for Marketplace enrollment, with private option enrollees comprising 80 percent of Marketplace enrollment.44 As of June 2015, the private option has resulted in an additional 220,000 people using the Arkansas Marketplace, raising enrollment from 54,000 to 273,000 and making it a more attractive market for issuers.45 Along with increasing the volume of Marketplace enrollees, the private option also makes the Arkansas Marketplace more attractive to issuers, who can secure new enrollees at any point during the year because Medicaid-eligible adults are not limited to signing up for coverage during open and special enrollment periods. In the 2015 open enrollment period, Arkansas had four carriers selling plans statewide, two of which had offered coverage in some areas of the state in 2014, and expanded statewide in 2015.46 Six issuers have submitted bids to offer plans in 2016. Many stakeholders credited the private option with driving a 2 percent average Marketplace premium rate decrease between 2014 and 2015, as well as the fact that, that according to the state insurance department, Arkansas had the second lowest average age of Marketplace beneficiaries in 2015.47 (Figure 3)

Figure 3: The Private Option accounts for 80% of total Arkansas Marketplace enrollment and enrollees are younger

Arkansas’s use of an auto-assignment algorithm that gave issuers an incentive to enter the Arkansas market may also have contributed to the jump in Marketplace issuers. The algorithm is explicitly designed to distribute private option enrollment across available plans, making the Arkansas Marketplace more appealing to new issuers who might otherwise find it difficult to break in and secure market share in the face of historical dominance by a single insurer. One stakeholder noted that plan options are similar enough to minimize the risk that auto-assignment disadvantages beneficiaries. Some, however, did suggest that the high rate of auto-assignment and the state’s current policy of paying the full premium cost of any certified silver-level Marketplace plan for private option enrollees could reduce incentives for issuers to compete on price. (As discussed below, however, the state plans to subsidize only selected Marketplace plans for private option enrollees beginning in the fall of 2015.)

Financing

Since it first became a possibility, there has been significant debate about the financing of the private option. While it will be some time before data are available to evaluate some of the key financing issues, stakeholders were able to provide some initial insights.

Because the state had no experience covering the expansion population, it was challenging for the state to negotiate budget neutrality with the federal government. Budget neutrality is a hypothetical exercise applicable to all Section 1115 waivers that requires states to demonstrate that the waiver will not cost the federal government more than it would have spent on the state’s Medicaid program without the waiver. If a state’s expenditures exceed its budget neutrality target, it is at risk of not receiving federal Medicaid matching funds for the excess spending.48 Notably, however, Arkansas secured a provision in the terms and conditions of its waiver that allows it to revisit the budget neutrality targets if the cost of serving newly-eligible adults exceeds expectations. CMS made this allowance for Arkansas and all other states with alternative coverage models because of the difficulty of establishing the budget neutrality baseline for a population with which states have little experience. Even so, the budget neutrality projections are important, and CMS and Arkansas faced two major challenges in establishing them for the private option. First, Arkansas had limited experience covering low-income adults, making it difficult to predict how much the state would have spent on such adults in the absence of the waiver. Second, and more fundamentally, state leaders believed that adding some 220,000 newly eligible adults to the existing fee-for-service Medicaid program would require the expansion of the state’s Medicaid provider network to ensure adequate access to care, particularly in rural areas. Consequently, Arkansas and CMS developed a “without waiver” baseline using historical spending on a similar population (low-income parents below 17 percent FPL who are covered under Arkansas’s traditional Medicaid program) and made adjustments to reflect the need for higher provider reimbursement rates in the fee-for-service system under a traditional expansion to achieve sufficient provider access. The baseline allowed Medicaid spending to increase at an estimated rate of approximately 4.7 percent a year, comparable to national Medicaid expenditure trends.49

Despite early concerns, the private option is on track to meet budget neutrality targets and may even outperform expectations. As with all Medicaid Section 1115 waivers, Arkansas must demonstrate budget neutrality over the life of the private option (2014 – 2016), not on a year-by-year basis. This allows the state to incur higher start-up costs and exceed its annual budget target in the early years of the waiver and make up for it in later years. In the early months of the private option, Arkansas’s actual per capita spending on private option enrollees was higher than projected, generating some controversy and debate. Now, however, the state’s actual per capita spending has dropped below projected levels, and concerns that the state might not meet budget neutrality over the life of the waiver have abated. In fact, the state’s success in keeping per capita expenditures below projected targets in 2015 when enrollment is significantly higher than in 2014 – and, thus, a more important factor in the state’s ability to meet budget neutrality over the three-year life of the waiver – means the state may potentially keep spending well below allowable levels. As noted above, the higher-than-expected per capita expenditures in the early months of 2014 are attributable in part to some enrollees selecting and receiving subsidies for plans that included supplemental coverage (such as dental services) not covered for newly eligible adults, an issue that the state Medicaid agency has now remedied. Stakeholders also pointed out that a recent state decision to limit the state’s payment of premiums to the two least expensive silver-level Marketplace plans or any plans with a premium within 10 percent of the cost of the second lowest cost silver plan, beginning in the fall of 2015, will likely solidify compliance with budget neutrality.50

The private option also will be evaluated based on whether it is “cost-effective,” a broader measure of the impact of the initiative. Under the terms of Arkansas’ waiver, the cost-effectiveness inquiry considers more factors than simply whether the program requires more or less federal Medicaid money to cover the same population through traditional Medicaid and instead is designed to evaluate both the costs and benefits of providing Medicaid coverage through Marketplace premium assistance.51 The state can take into account the private option’s impact on beneficiary access to care, Marketplace competitiveness, and reductions in churning between Medicaid and Marketplace coverage as income changes. Unlike the budget neutrality measure, cost-effectiveness is not used to establish limits on the availability of federal Medicaid matching funds, but it is an important measure of whether the private option has met its objectives as a whole. It will be some time before data are available to answer the larger and more complex question of cost-effectiveness, but early signs are that the value of the private option extends well beyond its impact on newly eligible adults. This includes improved access to care for private option enrollees and potential increases in provider capacity for the larger community; the impact on the cost of Marketplace coverage; and benefits to Arkansas’s providers.

Reports also find the private option has generated state savings. According to state officials, the private option saved Arkansas $30.8 million in fiscal year 2014, and the state expects to save an additional $88.8 million in fiscal year 2015. Another recent report projects state savings of $438 million from 2017 to 2021.52 Sources of savings include reductions in uncompensated care spending and in behavioral health care spending,53 as well as savings from moving people who previously received coverage under specialized Medicaid categories for adults with disabilities, women with breast or cervical cancer, and others into the expansion’s new eligibility group, for which the federal government pays the enhanced matching rate. In addition, Arkansas expects to collect $34.4 million in new revenue over 2014 and 2015 from taxes on providers and health plans, producing a total gain for the state budget of over $150 million in 18 months.54 Not included in these estimates is the potential effect on state health care spending and quality associated with requiring Marketplace issuers to participate in the state’s broader delivery system reform efforts on behalf of private option enrollees.

Looking Ahead

For now, the private option expansion is slated to continue at least through the end of 2016. Over the next several months, state policymakers will be charting the longer-term future of the private option in the context of broader Medicaid reform in Arkansas. Most stakeholders were reluctant to make firm predictions about the future of the private option, preferring to wait until the state legislative task force and Governor’s Medicaid Advisory Committee complete their work in December 2015. Many, however, speculated that the extension of coverage to newly eligible adults would continue in one form or another because the alternative would generate significant upheaval for the state’s residents and providers. Stakeholders also thought that key elements of the private option, including its use of private plans – rather than the fee-for-service system – would continue to have strong appeal to policymakers, although they might want to integrate the private option into broader Medicaid reforms. On the other hand, with the state expected to finance a share of the cost of covering newly eligible adults in the years ahead,55 stakeholders felt that answering some of the critical questions about the cost-effectiveness of the private option – relative to other Medicaid service delivery options available to the state – would be critical. Finally, the state’s interest in a Section 1332 waiver is strong, spurred by the potential flexibility it could provide to re-make Arkansas’s Marketplace. Discussion about the role that a Section 1332 waiver might play in Arkansas was just beginning at the time of the interviews, however, and stakeholders did not yet have detailed ideas about how such a waiver could be used. It, however, was noted that if the state seeks a Section 1332 waiver, it could potentially tap any federal savings attributed to the private option driving down the cost of Marketplace plans and, in turn, the cost to the federal government of providing tax credits to marketplace enrollees.56

Lessons for Other States

States that expand coverage realize substantial reductions in uninsured rates and provider uncompensated care costs along with increased access to care among beneficiaries, regardless of the mechanism used to implement an expansion. After expanding Medicaid through the private option, Arkansas realized considerable reductions in its non-elderly adult uninsured rate and providers’ uncompensated care costs along with increased beneficiary access to care. Unlike other effects of the private option in Arkansas, such as the impact on Marketplace enrollment, these gains were not unique to Arkansas’ Medicaid expansion delivery model. Most states that adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion did so without waiver authority and using their existing Medicaid delivery systems, which vary among the states from private capitated Medicaid managed care plans to managed fee-for-service models. In general, states that expanded coverage, regardless of delivery system, experienced the benefits of expansion.57

States have significant flexibility to tailor their Medicaid programs for newly eligible adults to fit their particular delivery system and broader policy agenda. In Arkansas, the private option met the needs of the state given that it had a fee-for-service system that was unlikely to be able to absorb more than 200,000 new enrollees without increases in provider payment rates and no Medicaid managed care infrastructure on which to build. In addition, Arkansas’s policymakers were committed to using private plans and competitive market forces as the mechanism for a coverage extension and for furthering the state’s delivery system reform efforts. The state had the ability to do so because its Marketplace operates as a Partnership model and can actively shape and monitor the plans offered , allowing for greater alignment between the Marketplace plans and Medicaid requirements. Many other states are not in this situation – they may have well-developed Medicaid managed care programs on which to build, a more limited ability to shape Marketplace plans because they do not operate as a State-based or Partnership model, or a different set of political and policy priorities. Even if the private option does not fit their particular circumstances, a larger lesson from Arkansas is that states have considerable flexibility to tailor coverage extensions to their unique circumstances and priorities.

Implementation of the private option has required unprecedented levels of cooperation between the state Medicaid agency and state insurance department and an enormous amount of time and effort on the part of the state’s leadership. State officials and other stakeholders had to work across their silos to develop Marketplace plans consistent with both Marketplace and Medicaid requirements and develop strategies for resolving issues where it initially was not clear whether the state Medicaid agency or insurance department was responsible. One of the biggest and most time-consuming challenges was bringing about what one stakeholder described as a “marriage of different mindsets” – insurance regulators are accustomed to viewing health insurance as the prepaid management of an actuarial risk pool whereas Medicaid officials more often view it as a cost-based enterprise under which the federal government matches the state’s incurred costs. Adding to the challenge was that the federal officials charged with overseeing Medicaid and Marketplaces also work in separate divisions of HHS, and they too had to find new ways to collaborate and provide clear guidance to Arkansas.

Strong collaboration with stakeholders and transparency were key to implementation of the private option in Arkansas, but could have been even stronger. Given the unprecedented nature of Arkansas’s initiative and rapid implementation timeline, the state worked closely with issuers, providers, and other stakeholders to prepare for the program’s launch well in advance of formal approval of Arkansas’s waiver. The state adopted a transparent and collaborative approach with carriers during implementation that helped them to navigate a highly fluid environment. One stakeholder described carriers as having almost real-time access to updates on the policy and fiscal assumptions behind the private option and credited this “tremendous transparency” with allowing issuers to design Marketplace plans consistent with Medicaid requirements and emerging fiscal estimates. Some interviewees, however, suggested that the state would have benefited from engagement with a broader group of stakeholders; some community health centers, in particular, suggested the state might have avoided the issues arising with respect to cost-based reimbursement if they had been more involved in the planning stages.

Conclusion

Stakeholder interviews revealed that the private option offers a path to coverage for close to 260,000 newly eligible adults in Arkansas, and enabled the state to use Marketplace plans to cover Medicaid beneficiaries in the absence of an established Medicaid managed care delivery system in the state. Early implementation experience reported by stakeholders suggests that the vast majority of beneficiaries are receiving much-needed care; the state has succeeded in keeping spending in line with its federal budget neutrality agreement; hospitals are experiencing unprecedented declines in their uncompensated care costs; and the state’s Marketplace is stronger and more robust because of the inclusion of private option enrollees. Arkansas continues to discuss what should come next for the private option; what, if anything, the state may do with the emerging opportunity to use a Section 1332 waiver; and whether the state should consider more sweeping changes to its larger delivery system for all Medicaid beneficiaries, including medically frail adults not enrolled in the private option. Any new approach will need to fit with the state’s mission and goals; be consistent with its delivery system; win the political sanction of the state’s leadership, including a super majority in the Arkansas legislature; and secure approval from the federal government.

This issue brief was prepared by Jocelyn Guyer and Naomi Shine of Manatt Health and MaryBeth Musumeci and Robin Rudowitz of the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Manatt Health has served as a consultant to the state of Arkansas on aspects of its Medicaid private option plan; this study was conducted independently of that work. The authors gratefully acknowledge the state policymakers and leaders, health plans, providers, consumer advocates and other stakeholders who participated in the interviews on which this issue brief is based. The authors also thank others at Manatt Health and the state who helped with research and review of this brief.