What Does the Recent Literature Say About Medicaid Expansion?: Impacts on Sexual and Reproductive Health

Issue Brief

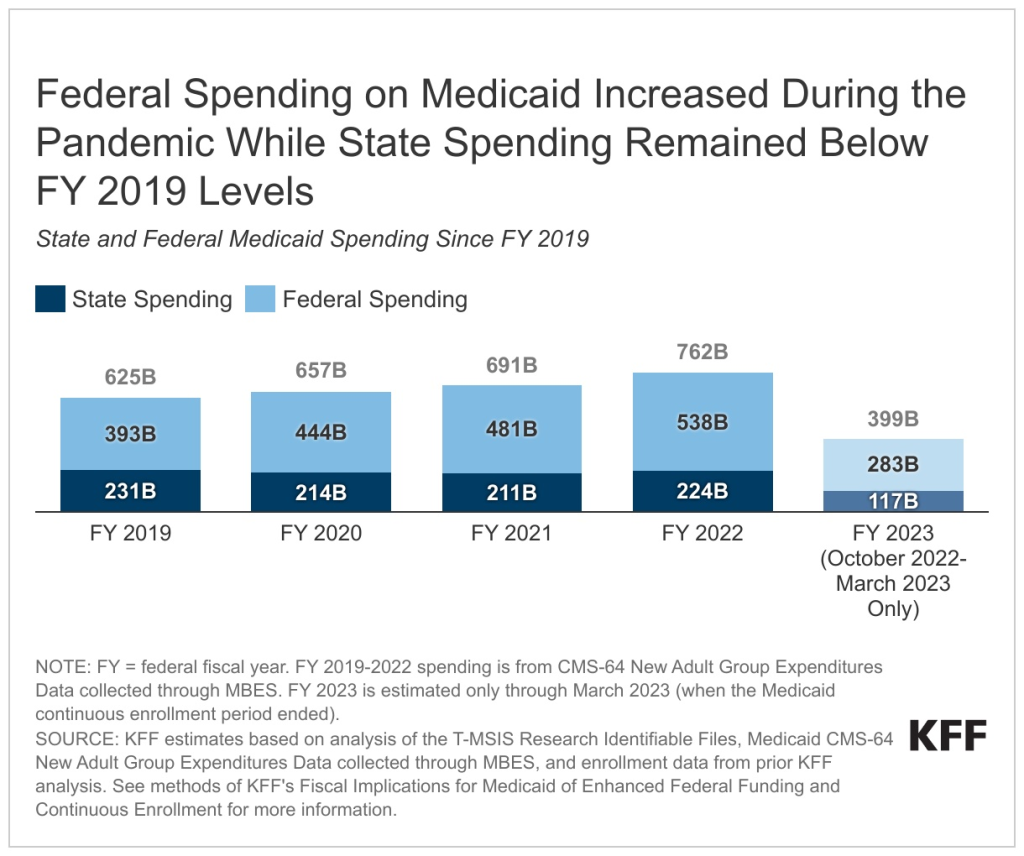

A substantial body of research has investigated effects of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion, adopted by all but 10 states as of June 2023. Prior KFF reports published in 2020 and 2021 reviewed more than 600 studies and concluded that expansion is linked to gains in coverage, improvement in access and health, and economic benefits for states and providers; these generally positive findings persist even as more recent research considers increasingly complex and specific outcomes. This research provides context for ongoing debates about whether to expand Medicaid in states that have not done so already, where coverage options for many low-income adults are limited and nearly two million individuals fall into a coverage gap.

Medicaid is the largest source of public funding for family planning services—which are a mandatory benefit within the program—and finances 4 in 10 births in the United States, as well as provides prenatal and postpartum coverage. Federal law requires all states, including those that have not expanded Medicaid, to provide Medicaid coverage to pregnant individuals with incomes up to at least 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL). However, coverage options for the pre-pregnancy and postpartum periods vary across states and are more limited in non-expansion states. Nationwide, nearly 900,000 women fall into the coverage gap in non-expansion states.1

This brief updates prior KFF literature reviews by summarizing 40 studies published between April 2021 and June 2023 on the impacts of Medicaid expansion on a range of sexual and reproductive health outcomes, including:

- health insurance coverage before, during, and after pregnancy;

- maternal and infant health access, utilization, and outcomes;

- family planning; and

- HIV care and prevention.

Consistent with prior research, recent studies identify positive effects of Medicaid expansion on coverage rates before, during, and after pregnancy; access to prenatal and postpartum care; birth and postpartum outcomes; use of the most effective contraceptive methods; and HIV screening and outcomes.

Our methodology is consistent with that of prior analyses. We conducted keyword searches of PubMed and other academic/health policy search engines to collect credible studies (published by a journal or by a nonpartisan research organization) on the impacts of the ACA Medicaid expansion. We then reviewed study abstracts to identify relevancy to sexual and reproductive health. Included study findings fall into four topic areas (Figure 1). Within each topic area, we first briefly summarize findings from earlier research (published between January 2014 and March 2021) and then highlight key findings from recent research that add to this body of evidence. For more information about earlier studies, see the 2021 and 2020 literature reviews. For citations from April 2021 through June 2023, see the Bibliography.

Insurance Coverage Before, During, and After Pregnancy

Prior studies overwhelmingly found that expansion increased postpartum coverage rates, as well as coverage prior to and during pregnancy. Although the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 created a new option to expand postpartum coverage to 12 months via a State Plan Amendment, current federal statute requires that pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage continue through just 60 days. Earlier research indicates that ACA Medicaid expansion has decreased coverage loss after this 60-day period ends: all prior studies that consider rates of insurance coverage after pregnancy find that expansion significantly increased postpartum coverage. Studies also suggest an association between expansion and increased coverage prior to and during pregnancy.

Most recent studies continue to find that expansion is associated with coverage gains in the pre-pregnancy, pregnancy, and postpartum periods. All recent studies that consider the impact of expansion on insurance coverage prior to conception and at birth find coverage gains.2 ,3 ,4 ,5 Also, four studies find increases in coverage during the postpartum period, including one that also found that racial disparities in such coverage decreased.6 ,7 ,8 ,9 One study considered Medicaid coverage post-abortion in Oregon and found a significant increase, as well as significant declines in lapses in enrollment.10 In contrast, two studies had mixed findings and found that postpartum coverage gains were not significant.11 ,12

Maternal and Infant Health: Access, Utilization, and Outcomes

Prior studies found that expansion increased access to health care for pregnant and postpartum women, and some suggested improvements in certain adverse pregnancy outcomes. Studies find that expansion increased access to and utilization of prenatal services—such as medications to treat opioid use disorder (MOUD) during pregnancy—as well as postpartum care. Additionally, all prior studies that consider impacts on maternal mortality or morbidity find significant declines, though findings on the impact of expansion on other health outcomes during pregnancy are mixed. Studies generally suggest an association between expansion and improvements in infant birth outcomes such as low birthweight, but most find no impact on infant mortality or find that improvements in infant mortality were concentrated among non-White infants.

Consistent with previous research, recent studies find that expansion is associated with increased access to and utilization of prenatal and postpartum care. Most studies in this area find that expansion resulted in increased utilization of at least one prenatal or postpartum service.13 ,14 ,15 ,16 ,17 ,18 ,19 ,20 These findings include increased use of services during pregnancy or childbirth, such as receipt of adequate prenatal care (both prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic) and of MOUD, as well as of services during the postpartum period, such as breast pump claims and treatment for postpartum depression. Additionally, two studies find that Medicaid expansion may have promoted access to obstetrician-gynecologist (OB-GYN) care: by increasing the likelihood that OB-GYN practices have onsite resources to address psychosocial needs, and by facilitating access to intrapartum care for White and Hispanic women living in rural counties with obstetric unit closures.21 ,22 A smaller number of studies find no impact of expansion on utilization of certain prenatal/postpartum services (such as early prenatal care), nor on access to providers (such as hospital-based obstetric units).23 ,24 ,25 ,26 ,27 ,28

Recent studies on the impact of expansion on adverse outcomes during pregnancy, birth, or postpartum are mixed. Several studies identify that expansion is associated with improvements in at least one health outcome.29 ,30 ,31 ,32 ,33 These findings include decreased incidence of adverse outcomes prior to pregnancy and at birth:

- Improved pre-pregnancy health outcomes: One study found that expansion was associated with significant declines in self-reported pre-pregnancy depression.34

- Improved maternal outcomes at childbirth: Consistent with prior research, one recent study considering maternal morbidity in New York found a significant decrease in incidence, and that this decrease was significantly greater for low- versus high-income women.35

- Improved infant outcomes at childbirth: Two studies found that expansion was associated with lower rates of infant mortality (one of which identified a particular impact among Hispanic infants, similar to earlier research).36 ,37 One study found that expansion decreased the rate of low birth weight among infants born to mothers with hypertension in pregnancy.38 Finally, one study found that expansion reduced racial/ethnic disparities in infant health following rural obstetric unit closures.39

However, a similar number of studies find no impact of expansion on certain pregnancy or postpartum health outcomes, including incidences of gestational hypertension/diabetes and of postpartum depressive symptoms.40 ,41 ,42 ,43 ,44 ,45 ,46

Family Planning

Prior literature reviews indicated that expansion increased utilization of the most effective contraception methods but had little or no effect on overall contraception use. Medicaid is the primary funding source for family planning services for low-income people, with state programs required to cover all prescription contraceptives. Although the literature generally indicates that expansion has had little effect on contraception use overall, numerous studies identify an increased use of the most effective, long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), which includes IUDs and implants.

Recent studies find that expansion increased rates of LARC utilization and may have increased overall contraception use among some populations. Recent studies identify increases in utilization of LARC, short-acting contraception, and overall contraception for certain populations.47 ,48 ,49 ,50 ,51 ,52

- Increased LARC utilization: Three studies find increased use of LARC: among all Medicaid enrollees, among postpartum individuals, and among sexually active high school students.53 ,54 ,55

- Increased short-acting contraception utilization: One study found that physicians in Medicaid expansion states provided significantly more enrollees with short-acting hormonal birth control methods compared to physicians in non-expansion states.56

- Increased contraception utilization overall (short- and long-acting): One study found a significant increase in the use of any postpartum contraception method, driven by a shift from short-acting and non-prescription contraceptive methods to higher-cost, more effective forms of contraception.57 Two studies pointed to increased use of contraceptive services and counseling among Medicaid-enrolled women of reproductive age in Oregon.58 ,59

Finally, consistent with earlier research, two studies found no significant impact of expansion on overall contraception use for certain populations (students and postpartum individuals).60 ,61 Another study found that physicians in expansion and non-expansion states provided similar numbers of enrollees with LARC methods in 2016.62

A couple of recent studies suggest that increased access to family planning care after expansion may have decreased birth rates and short interpregnancy intervals, but others find no effect on these outcomes. One study found that expansion resulted in an overall decrease in live births among low-income women of reproductive age, particularly among subgroups with historically higher rates of unintended pregnancy (including unmarried, Hispanic, and American Indian and Alaskan Native women).63 Another study found that expansion resulted in a decreased risk of short interpregnancy intervals (less than 12 months between births), which the authors note have a known association with poor maternal and infant health outcomes.64 In contrast, three other studies find no impact of expansion on these or similar outcomes, including one study that found no impact on overall rates of early postpartum pregnancies but that such pregnancies did significantly decrease among Black patients.65 ,66 ,67

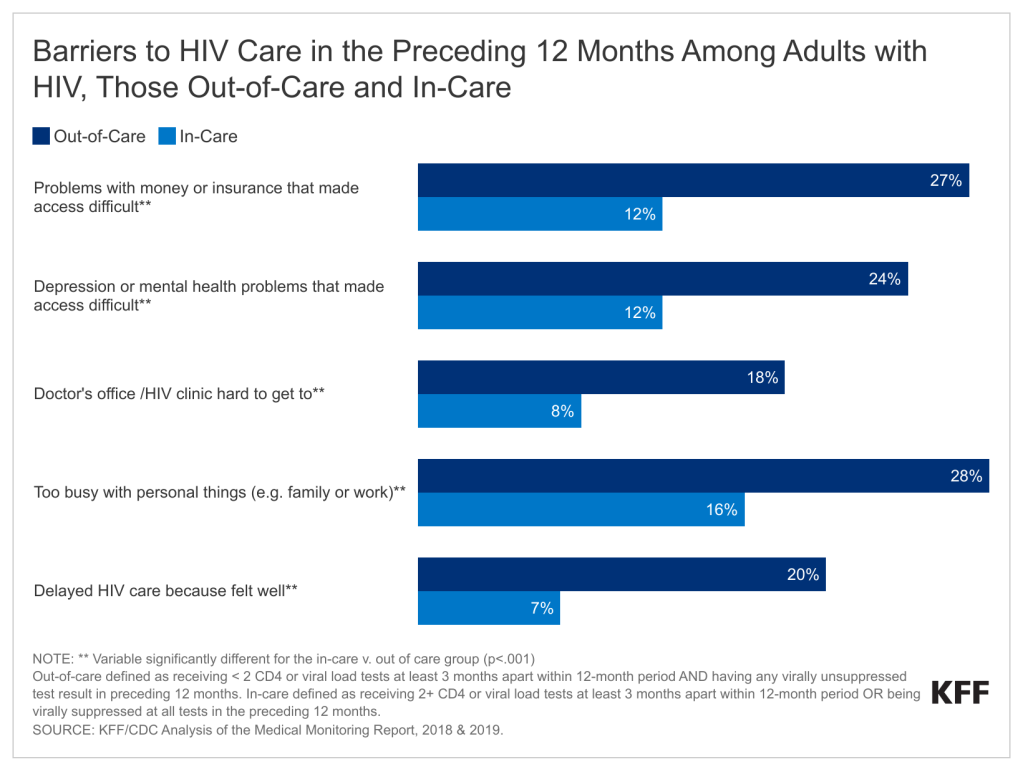

HIV Care and Prevention Outcomes

Prior studies suggest that expansion increased rates of HIV screening as well as health outcomes for those diagnosed with HIV. Prior to the ACA, many people with HIV faced limited access to insurance coverage. Research finds that expansion increased insurance coverage rates among people with or at risk of HIV. Prior studies also indicate that expansion led to increases in HIV test and diagnosis rates despite no change in actual HIV incidence. Finally, studies find that expansion is associated with increased utilization of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV and improved quality of care for patients with HIV.

Most recent studies continue to find positive effects of expansion on HIV screening rates and outcomes.68 Consistent with prior research, recent studies find an association between expansion and increased rates of HIV testing.69 ,70 Also, a study found significant coverage gains among women with or at risk of contracting HIV.71 Two studies on Medicaid expansion and PrEP both found positive impacts. The first found a small but significant increase in the likelihood that men (and transgender or nonbinary individuals) who have sex with men (MSM) were taking PrEP to prevent HIV.72 The second found that Medicaid expansion was associated with a higher share of Google searches for PrEP keywords, potentially indicating an higher awareness of and interest in PrEP due to increased access.73 Finally, a study that following expansion, people with HIV experienced a significant increase in linkages to care after diagnosis, but no change in viral suppression of HIV (which the authors note could be in part because of state variation in Medicaid coverage policies for people with HIV).74

Emerging Research

A small number of additional emerging studies include findings on:

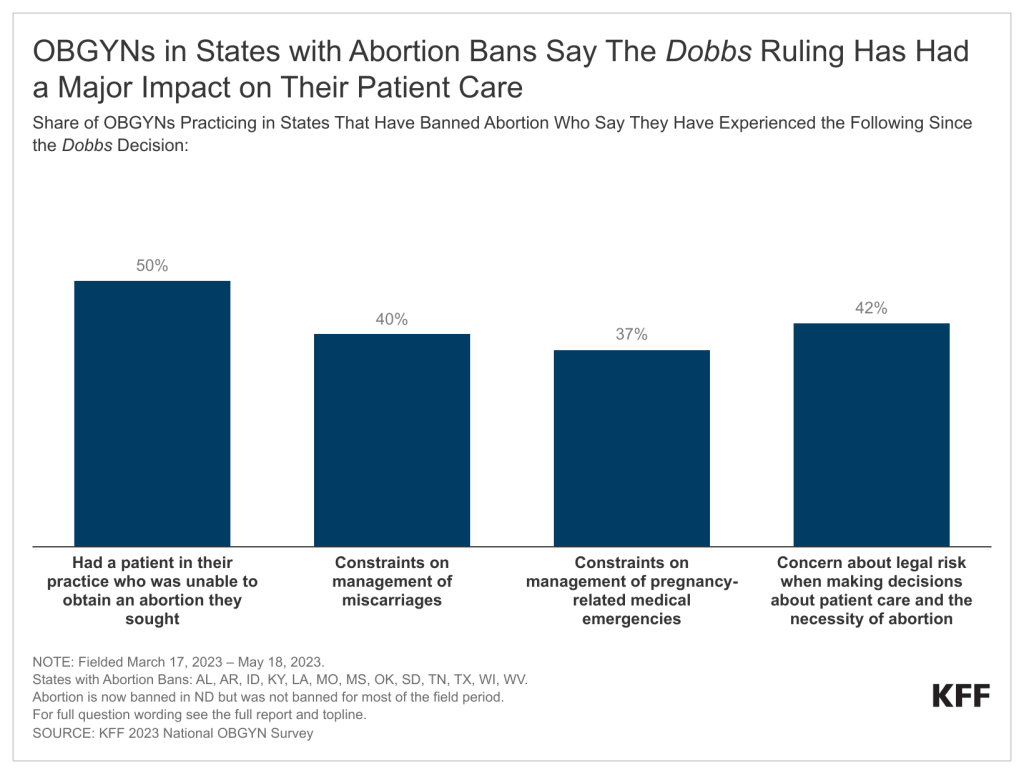

Abortion: The Hyde Amendment blocks states from using federal funds to pay for abortion services under Medicaid in most instances.75 However, 17 states (all of which have expanded Medicaid) use state-only Medicaid funds to cover all or most medically accessible abortions. A recent study found no impact of Medicaid expansion on the abortion rate nationwide, though the authors note that this analysis was exploratory and that future research on expansion’s impact on abortions is necessary.76 Research in this area may continue particularly as abortion access across states continues to evolve following the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision.

LGBTQ+ individuals: Earlier research found gains in Medicaid coverage among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals following expansion. Similarly, one recent study found that following Medicaid expansion, overall insurance coverage rates increased for low-income individuals in same-sex couples, with larger gains for women versus men. The study also noted no significant impact on the likelihood of being employed for either low-income men or women in same-sex couples.77 Another study found that Medicaid expansion was associated with higher odds of having health coverage among transgender adults.78

Taken together, the 40 new studies summarized in this brief add to the body of prior research finding positive effects of expansion on sexual and reproductive health. This research provides context for ongoing debates about whether to expand Medicaid in states that have not done so already. As states unwind the pandemic-era continuous enrollment provision in 2023, many individuals who qualified for Medicaid through the pregnancy pathway during the pandemic are at risk of losing Medicaid coverage. These individuals will have more coverage options in states that have expanded Medicaid. Looking ahead, future research may consider the impacts of expansion against the backdrop of evolving national and state landscapes around Medicaid eligibility as well as access to reproductive health care.

The authors thank Meghana Ammula (formerly of KFF) for her assistance reviewing recently published studies included in this brief.

Bibliography

Bibliography, April 2021 to June 2023

Bibliography (.pdf)

Endnotes

- KFF analysis of 2021 American Community Survey (ACS). ↩︎

- Erica Eliason, Jamie Daw, and Heidi Allen, “Association of Medicaid vs Marketplace Eligibility With Maternal Coverage and Access to Prenatal and Postpartum Care,” JAMA Network Open 4 no. 12 (December 2021), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37383 ↩︎

- Jean Guglielminotti, Ruth Landau, and Guohua Li, “The 2014 New York State Medicaid Expansion and Severe Maternal Morbidity During Delivery Hospitalizations,” Anesthesia & Analgesia 133 no. 2 (August 2021): 340-348, https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005371 ↩︎

- Claire E. Margerison, Katlyn Hettinger, Robert Kaestner, Sidra Goldman-Mellor, and Danielle Gartner, “Medicaid Expansion Associated with Some Improvements in Perinatal Mental Health,” Health Affairs 40 no. 10 (October 2021), https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00776 ↩︎

- Bradley Corallo and Brittni Frederiksen, How Does the ACA Expansion Affect Medicaid Coverage Before and During Pregnancy? (Washington, DC: KFF, October 2022), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/how-does-the-aca-expansion-affect-medicaid-coverage-before-and-during-pregnancy/ ↩︎

- Lindsey Rose Bullinger, Kosali Simon, and Brownsyne Tucker Edmonds, “Coverage Effects of the ACA’s Medicaid Expansion on Adult Reproductive-Aged Women, Postpartum Mothers, and Mothers with Older Children,” Maternal and Child Health Journal 26 (March 2022): 1104-1114, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-022-03384-8 ↩︎

- Maria Steenland, Ira Wilson, and Kristen Matteson, “Association of Medicaid Expansion in Arkansas With Postpartum Coverage, Outpatient Care, and Racial Disparities,” JAMA Health Forum 2 no. 12 (December 2021), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.4167 ↩︎

- Erica Eliason, Jamie Daw, and Heidi Allen, “Association of Medicaid vs Marketplace Eligibility With Maternal Coverage and Access to Prenatal and Postpartum Care,” JAMA Network Open 4 no. 12 (December 2021), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37383 ↩︎

- Bradley Corallo, Jennifer Tolbert, Heather Saunders, and Brittni Frederiksen, Medicaid Enrollment Patterns During the Postpartum Year (Washington, DC: KFF, July 2022), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-enrollment-patterns-during-the-postpartum-year/ ↩︎

- Susannah E. Gibbs and S. Marie Harvey, “Postabortion Medicaid Enrollment and the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion in Oregon,” Journal of Women’s Health 31 no. 1 (January 2022): 55-62, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8941 ↩︎

- Claire E. Margerison, Katlyn Hettinger, Robert Kaestner, Sidra Goldman-Mellor, and Danielle Gartner, “Medicaid Expansion Associated with Some Improvements in Perinatal Mental Health,” Health Affairs 40 no. 10 (October 2021), https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00776 ↩︎

- Erica Eliason, Jamie Daw, and Heidi Allen, “Association of Medicaid vs Marketplace Eligibility With Maternal Coverage and Access to Prenatal and Postpartum Care,” JAMA Network Open 4 no. 12 (December 2021), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37383 ↩︎

- Summer Hawkins, Krisztina Horvath, Alice Noble, and Christopher Baum, “ACA and Medicaid Expansion Increased Breast Pump Claims and Breastfeeding for Women with Public and Private Insurance,” Women’s Health Issues 32 no. 2 (March 2022): 114-121, https://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(21)00158-4/fulltext ↩︎

- Ian Everitt et al., “Association of State Medicaid Expansion Status With Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy in a Singleton First Live Birth,” Circulation: Cardiovasucular Quality and Outcomes 15 no. 1 (January 2022), https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.008249 ↩︎

- Erica Eliason, Jamie Daw, and Heidi Allen, “Association of Medicaid vs Marketplace Eligibility With Maternal Coverage and Access to Prenatal and Postpartum Care,” JAMA Network Open 4 no. 12 (December 2021), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37383 ↩︎

- Maria Steenland, Ira Wilson, and Kristen Matteson, “Association of Medicaid Expansion in Arkansas With Postpartum Coverage, Outpatient Care, and Racial Disparities,” JAMA Health Forum 2 no. 12 (December 2021), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.4167 ↩︎

- Sugy Choi et al., “Estimating The Impact on Initiating Medications for Opioid Use Disorder of State Policies Expanding Medicaid and Prohibiting Substance Use During Pregnancy,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 129 pt. A (December 2021), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0376871621006578 ↩︎

- Maria Steenland and Amal Trivedi, “Association of Medicaid Expansion With Postpartum Depression Treatment in Arkansas,” JAMA Health Forum 4 no. 2 (February 2023), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.5603 ↩︎

- Pinka Chatterji, Hanna Glenn, Sara Markowitz, and Jennifer Karas Montez, ACA Medicaid Expansions and Maternal Morbidity (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 30770, December 2022), https://www.nber.org/papers/w30770 ↩︎

- Hyunjung Lee and Gopal Singh, “The Differential Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Prenatal Care Utilization Among US Women by Medicaid Expansion and Race and Ethnicity,” Journal of Public Health Management and Practice Epub ahead of print (December 2022), https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001698 ↩︎

- Gabriela Weigel, Brittni Frederiksen, Usha Ranji, and Alina Salganicoff, “Screening and Intervention for Psychosocial Needs by U.S. Obstetrician-Gynecologists,” Journal of Women’s Health 31 no. 6 (June 2022): 887-894, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2021.0236 However, this study found no significant impact of expansion on the likelihood that OB-GYN practices report actually screening all patients for these needs. ↩︎

- Pinka Chatterji, Chun-Yu Ho, and Xue Wu, Obstetric Unit Closures and Racial/Ethnic Disparity in Health (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 30986, February 2023), https://www.nber.org/papers/w30986 ↩︎

- Erica Eliason, Jamie Daw, and Heidi Allen, “Association of Medicaid vs Marketplace Eligibility With Maternal Coverage and Access to Prenatal and Postpartum Care,” JAMA Network Open 4 no. 12 (December 2021), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37383 ↩︎

- Claire Margerison, Robert Kaestner, Jiajia Chen, and Colleen MacCallum-Bridgers, “Impacts of Medicaid Expansion Before Conception on Prepregnancy Health, Pregnancy Health, and Outcomes,” American Journal of Epidemiology 190 no. 8 (August 2021): 1488-1498, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwaa289 ↩︎

- Maria Steenland, Ira Wilson, and Kristen Matteson, “Association of Medicaid Expansion in Arkansas With Postpartum Coverage, Outpatient Care, and Racial Disparities,” JAMA Health Forum 2 no. 12 (December 2021), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.4167 ↩︎

- Erica Eliason, Jamie Daw, and Heidi Allen, “Association of Medicaid vs Marketplace Eligibility With Maternal Coverage and Access to Prenatal and Postpartum Care,” JAMA Network Open 4 no. 12 (December 2021), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37383 ↩︎

- Gabriela Weigel, Brittni Frederiksen, Usha Ranji, and Alina Salganicoff, “Screening and Intervention for Psychosocial Needs by U.S. Obstetrician-Gynecologists,” Journal of Women’s Health 31 no. 6 (June 2022): 887-894, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2021.0236 ↩︎

- Caitlin Carroll, Julia Interrante, Jamie Daw, and Katy Backes Kozhimannil, “Association Between Medicaid Expansion and Closure of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services,” Health Affairs 41 no. 4 (April 2022), https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01478 ↩︎

- Jean Guglielminotti, Ruth Landau, and Guohua Li, “The 2014 New York State Medicaid Expansion and Severe Maternal Morbidity During Delivery Hospitalizations,” Anesthesia & Analgesia 133 no. 2 (August 2021): 340-348, https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005371 ↩︎

- Joanne Constantin and George Wehby, “Effects of Recent Medicaid Expansions on Infant Mortality by Race and Ethnicity,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 64 no. 3 (March 2023): 377-384, https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(22)00498-6/fulltext ↩︎

- Claire E. Margerison, Katlyn Hettinger, Robert Kaestner, Sidra Goldman-Mellor, and Danielle Gartner, “Medicaid Expansion Associated with Some Improvements in Perinatal Mental Health,” Health Affairs 40 no. 10 (October 2021), https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00776 ↩︎

- Ian Everitt et al., “Association of State Medicaid Expansion Status With Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy in a Singleton First Live Birth,” Circulation: Cardiovasucular Quality and Outcomes 15 no. 1 (January 2022), https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.008249 ↩︎

- Maria Steenland and Laura Wherry, “Medicaid Expansion Led To Reductions In Postpartum Hospitalizations,” Health Affairs 42 no. 1 (January 2023): 18-25, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00819 ↩︎

- Claire E. Margerison, Katlyn Hettinger, Robert Kaestner, Sidra Goldman-Mellor, and Danielle Gartner, “Medicaid Expansion Associated with Some Improvements in Perinatal Mental Health,” Health Affairs 40 no. 10 (October 2021), https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00776 ↩︎

- Jean Guglielminotti, Ruth Landau, and Guohua Li, “The 2014 New York State Medicaid Expansion and Severe Maternal Morbidity During Delivery Hospitalizations,” Anesthesia & Analgesia 133 no. 2 (August 2021): 340-348, https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005371 In contrast, a national study (Chatterji et al. 2022), cited below, found no significant impact on severe maternal morbidity, but did not limit this analysis by income. ↩︎

- Joanne Constantin and George Wehby, “Effects of Recent Medicaid Expansions on Infant Mortality by Race and Ethnicity,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 64 no. 3 (March 2023): 377-384, https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(22)00498-6/fulltext ↩︎

- Jessian Munoz, “Preterm Birth and Foetal-Neonatal Death Rates Associated With the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion (2014–19),” Journal of Public Health 45 no. 1 (March 2023): 99–101, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab377 ↩︎

- Ian Everitt et al., “Association of State Medicaid Expansion Status With Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy in a Singleton First Live Birth,” Circulation: Cardiovasucular Quality and Outcomes 15 no. 1 (January 2022), https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.008249 ↩︎

- Pinka Chatterji, Chun-Yu Ho, and Xue Wu, Obstetric Unit Closures and Racial/Ethnic Disparity in Health (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 30986, February 2023), https://www.nber.org/papers/w30986 ↩︎

- Joanne Constantin and George Wehby, “Effects of Recent Medicaid Expansions on Infant Mortality by Race and Ethnicity,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 64 no. 3 (March 2023): 377-384, https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(22)00498-6/fulltext ↩︎

- Claire E. Margerison, Katlyn Hettinger, Robert Kaestner, Sidra Goldman-Mellor, and Danielle Gartner, “Medicaid Expansion Associated with Some Improvements in Perinatal Mental Health,” Health Affairs 40 no. 10 (October 2021), https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00776 ↩︎

- Ian Everitt et al., “Association of State Medicaid Expansion Status With Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy in a Singleton First Live Birth,” Circulation: Cardiovasucular Quality and Outcomes 15 no. 1 (January 2022), https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.008249 ↩︎

- Claire Margerison, Robert Kaestner, Jiajia Chen, and Colleen MacCallum-Bridgers, “Impacts of Medicaid Expansion Before Conception on Prepregnancy Health, Pregnancy Health, and Outcomes,” American Journal of Epidemiology 190 no. 8 (August 2021): 1488-1498, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwaa289 ↩︎

- Anna Austin, Rebeccah Sokol, and Caroline Rowland, “Medicaid Expansion and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms: Evidence From the 2009-2018 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System Survey,” Annals of Epidemiology 68 (April 2022): 9-15, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1047279721003537 ↩︎

- Maria Steenland and Laura Wherry, “Medicaid Expansion Led To Reductions In Postpartum Hospitalizations,” Health Affairs 42 no. 1 (January 2023): 18-25, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00819 ↩︎

- Pinka Chatterji, Hanna Glenn, Sara Markowitz, and Jennifer Karas Montez, ACA Medicaid Expansions and Maternal Morbidity (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 30770, December 2022), https://www.nber.org/papers/w30770 ↩︎

- Lydia Pace, Indrani Saran, and Summer Sherburne Hawkins, “Impact of Medicaid Eligibility Changes on Long-acting Reversible Contraception Use in Massachusetts and Maine,” Medical Care 60 no. 2 (February 2022): 119-124, https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001666 ↩︎

- Erica L. Eliason, Amanda Spishak-Thomas, and Maria W. Steenland, “Association of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions with Postpartum Contraceptive Use and Early Postpartum Pregnancy,” Contraception 113 (September 2022): 42-48, https://www.contraceptionjournal.org/article/S0010-7824(22)00060-9/fulltext ↩︎

- Greta Kilmer et al., “Medicaid Expansion and Contraceptive Use Among Female High-School Students,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 63 no. 4 (October 2022): 592-602, https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(22)00244-6/fulltext ↩︎

- Mandar Bodas et al., “Association of Primary Care Physicians’ Individual- and Community-Level Characteristics With Contraceptive Service Provision to Medicaid Beneficiaries,” JAMA Health Forum 4 no. 3 (March 2023), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.0106 ↩︎

- Susannah E. Gibbs, S. Marie Harvey, Annie Larson, Jangho Yoon, and Jeff Luck, “Contraceptive Services After Medicaid Expansion in a State with a Medicaid Family Planning Waiver Program,” Journal of Women’s Health 30 no. 5 (May 2021): 750-757, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8351 ↩︎

- Mandana Masoumirad, S. Marie Harvey, Linh N. Bui, and Jangho Yoon, “Use of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Among Women Living in Rural and Urban Oregon: Impact of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion,” Journal of Women’s Health 32 no. 3 (March 2023): 300-310, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2022.0308 ↩︎

- Lydia Pace, Indrani Saran, and Summer Sherburne Hawkins, “Impact of Medicaid Eligibility Changes on Long-acting Reversible Contraception Use in Massachusetts and Maine,” Medical Care 60 no. 2 (February 2022): 119-124, https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001666 ↩︎

- Erica L. Eliason, Amanda Spishak-Thomas, and Maria W. Steenland, “Association of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions with Postpartum Contraceptive Use and Early Postpartum Pregnancy,” Contraception 113 (September 2022): 42-48, https://www.contraceptionjournal.org/article/S0010-7824(22)00060-9/fulltext ↩︎

- Greta Kilmer et al., “Medicaid Expansion and Contraceptive Use Among Female High-School Students,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 63 no. 4 (October 2022): 592-602, https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(22)00244-6/fulltext ↩︎

- Mandar Bodas et al., “Association of Primary Care Physicians’ Individual- and Community-Level Characteristics With Contraceptive Service Provision to Medicaid Beneficiaries,” JAMA Health Forum 4 no. 3 (March 2023), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.0106 ↩︎

- Erica L. Eliason, Amanda Spishak-Thomas, and Maria W. Steenland, “Association of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions with Postpartum Contraceptive Use and Early Postpartum Pregnancy,” Contraception 113 (September 2022): 42-48, https://www.contraceptionjournal.org/article/S0010-7824(22)00060-9/fulltext ↩︎

- Susannah E. Gibbs, S. Marie Harvey, Annie Larson, Jangho Yoon, and Jeff Luck, “Contraceptive Services After Medicaid Expansion in a State with a Medicaid Family Planning Waiver Program,” Journal of Women’s Health 30 no. 5 (May 2021): 750-757, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8351 ↩︎

- Mandana Masoumirad, S. Marie Harvey, Linh N. Bui, and Jangho Yoon, “Use of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Among Women Living in Rural and Urban Oregon: Impact of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion,” Journal of Women’s Health 32 no. 3 (March 2023): 300-310, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2022.0308 ↩︎

- Greta Kilmer et al., “Medicaid Expansion and Contraceptive Use Among Female High-School Students,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 63 no. 4 (October 2022): 592-602, https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(22)00244-6/fulltext ↩︎

- Erica Eliason, Jamie Daw, and Heidi Allen, “Association of Medicaid vs Marketplace Eligibility With Maternal Coverage and Access to Prenatal and Postpartum Care,” JAMA Network Open 4 no. 12 (December 2021), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37383 ↩︎

- Mandar Bodas et al., “Association of Primary Care Physicians’ Individual- and Community-Level Characteristics With Contraceptive Service Provision to Medicaid Beneficiaries,” JAMA Health Forum 4 no. 3 (March 2023), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.0106 ↩︎

- Erica L. Eliason, Jamie R. Daw, and Heidi L. Allen, “Association of Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions with Births Among Low-Income Women of Reproductive Age,” Journal of Women’s Health 31 no. 7 (July 2022): 949-956, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2021.0451 ↩︎

- Kriya S. Patel, Juliana Bakk, Meredith Pensak, Emily DeFranco, “Influence of Medicaid Expansion on Short Interpregnancy Interval Rates in the United States,” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology Maternal-Fetal Medicine 3 no. 6 (November 2021), https://www.ajogmfm.org/article/S2589-9333(21)00179-8/fulltext ↩︎

- Erica L. Eliason, Amanda Spishak-Thomas, and Maria W. Steenland, “Association of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions with Postpartum Contraceptive Use and Early Postpartum Pregnancy,” Contraception 113 (September 2022): 42-48, https://www.contraceptionjournal.org/article/S0010-7824(22)00060-9/fulltext ↩︎

- Danielle Gartner, Robert Kaestner, and Claire Margerison, “Impacts of the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid Expansion on Live Births,” Epidemiology 33 no. 3 (May 2022): 406-414, https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000001462 ↩︎

- Can Liu et al., “Impact of Medicaid Expansion on Interpregnancy Interval,” Womens Health Issues 32 no. 3 (May 2022): 226-234, https://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(21)00190-0/fulltext ↩︎

- Consistent with prior analysis, note that study findings on screening and outcomes related to HPV, as well as gynecological cancer generally, are included in our discussion of research on the impact of expansion on cancer-related outcomes. ↩︎

- Suhang Song and James Kucik, “Trends in the Impact of Medicaid Expansion on the Use of Clinical Preventive Services,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 62 no. 5 (May 2022): 752-762, https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(21)00595-X/fulltext ↩︎

- Toni Romero and Branco Ponomariov, “The Effect of Medicaid Expansion on Access to Healthcare, Health Behaviors and Health Outcomes Between Expansion and Non-Expansion States,” Evaluation and Program Planning Epub ahead of print (May 2023), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2023.102304 ↩︎

- Andrew Edmonds et al., “Impacts of Medicaid Expansion on Health Insurance and Coverage Transitions among Women with or at Risk for HIV in the United States,” Womens Health Issues 32 no. 5 (September-October 2022): 450-460, https://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(22)00027-5/fulltext ↩︎

- Pedro Botti Carneiro et al., “Demographic, Clinical Guideline Criteria, Medicaid Expansion and State of Residency: a Multilevel Analysis of PrEP Use on a Large US Sample,” BMJ Open 12 no. 2 (February 2022), https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/12/2/e055487.info ↩︎

- Bita Fayaz Farkhad, Mohammadreza Nazari, Man-pui Sally Chan, and Dolores Albarracín, “State Health Policies and Interest in PrEP: Evidence from Google Trends,” AIDS Care 34 no. 3 (2022): 331-339, https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2021.1934381 ↩︎

- J. Logan et al., “HIV Care Outcomes in Relation to Racial Redlining and Structural Factors Affecting Medical Care Access Among Black and White Persons with Diagnosed HIV—United States, 2017,” AIDS and Behavior 26 (March 2022): 2941–2953, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03641-5 ↩︎

- The Hyde amendment includes exceptions for pregnancies that are the result of rape, incest, or if the pregnant person’s life is in danger. ↩︎

- In particular, the abortion analysis was not restricted to women with Medicaid-eligible incomes and was not limited to only states that cover abortions in Medicaid. Erica L. Eliason, Jamie R. Daw, and Heidi L. Allen, “Association of Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions with Births Among Low-Income Women of Reproductive Age,” Journal of Women’s Health 31 no. 7 (July 2022): 949-956, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2021.0451 ↩︎

- Samuel Mann et al., “Effects of the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid Expansion on Health Insurance Coverage for Individuals in Same-sex Couples,” Health Services Research 58 no. 3 (June 2023): 612-621, https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.14128 ↩︎

- Nguyen Tran, Kellan Baker, Elle Lett, and Ayden Scheim, “State-Level Heterogeneity in Associations Between Structural Stigma and Individual Health Care Access: A Multilevel Analysis of Transgender Adults in the United States,” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 28 no. 2 (April 2023): 109-118, https://doi.org/10.1177/13558196221123413 ↩︎