The U.S. Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) Initiative: What You Need to Know

What is it?

The “Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative: A Plan for America” (EHE) is a federal effort to reduce new HIV infections in the United States by 75% in five years and by 90% in ten years and includes four “pillars”: diagnose, treat, prevent and respond (see below). It was launched by the Trump Administration in 2019, building on efforts made by the Obama Administration; President Biden has also expressed commitment to “ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2025” and signaled that they will continue the initiative. However, it remains to be seen if the new administration will make changes to the EHE. In addition, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, HIV programs in general, and the EHE effort, have been slowed down.

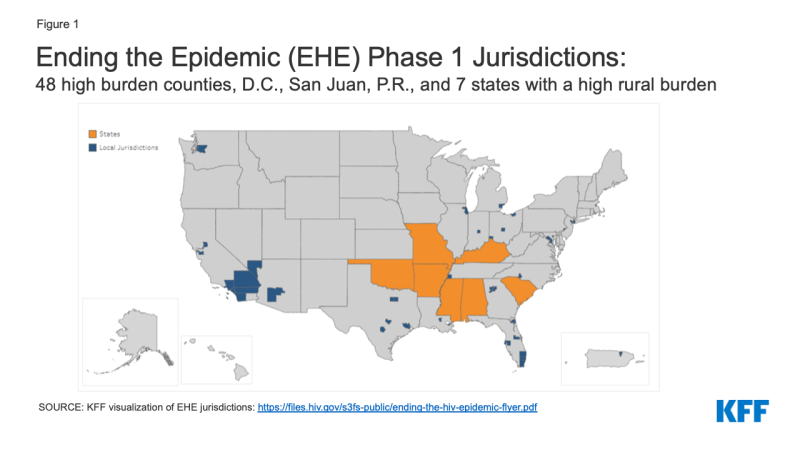

Where are the targeted jurisdictions?

During “Phase 1,” the initiative runs from 2020-2025 and focuses efforts on the regions hardest hit by the HIV epidemic. Its reach extends to the 48 counties that had the highest number of HIV diagnoses between 2016 and 2017, as well as San Juan, Puerto Rico, and Washington D.C. It also focuses on seven states with a substantial rural burden. More than 50% of HIV diagnoses in the US occur in these 48 counties, D.C., and San Juan.

Phase II of the initiative is set to begin in 2026 during which EHE efforts will be more widely disseminated across the nation and Phase III will focus on providing care and treatment and intensive case management aimed at keeping the number of new HIV infections below 3,000 per year.

How is it Funded?

The commitment to “ending the HIV epidemic” has been accompanied by additional federal funding, including with reprogrammed FY 2019 funding and new Congressional appropriations in since FY 2020. Funding in FY 2019 consisted of a small number of grants reprogramed from the Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative (MAI) fund, totaling $35 million, to launch the initiative. The first influx of new funding, through congressional appropriations, was provided in FY 2020, totaling $266 million and that level has increased each year, now with the FY 2023 level totaling $573.25 million. (See Table 1)

| Table 1: Ending the Epidemic Funding, FY 2019 – FY 2023 (in Millions) | ||||||||

| FY 2019 Allocation | FY 2020 Enacted | FY 2021 Enacted | FY 2022 Enacted |

FY 2023 Enacted | FY 2024 Enacted |

$ Change FY 2023 – FY 2024 |

% Change FY 2022 – FY 2023 |

|

| HHS (general) | $6 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CDC | $14 | $140 | $175 | $195 | $220 | $220 | $0 | NA |

| HRSA | ||||||||

| Ryan White | $0.98 | $70 | $105 | $125 | $165 | $165 | $0 | NA |

| Health Centers | — | $50 | $102.25 | $122.25 | $157.25 | $157.25 | $0 | NA |

| Health Centers (rural health TA) | — | $1 | $1.5 | NA | NA | NA | — | — |

| IHS | $2.4 | $0 | $5 | $5 | $5 | $5 | $0 | NA |

| NIH | $11.3 | $6 | $16 | $26 | $26 | $26 | $0 | NA |

| TOTAL | $34.68 | $267 | $404.75 | $473.25 | $573.25 | $573.25 | $0 | NA |

| NOTE: FY 2019 funding was reprogramed from other accounts and does not represent a congressional appropriation. SOURCE: Budget requests, appropriations documents, and https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/funding |

||||||||

Agency funding is distributed via grants to the targeted jurisdictions, as well as to support related efforts. For additional detail, see our EHE funding tracker.

It is important to note that while EHE funding represents a significant increase for certain agencies, it still accounts for a relatively small share of total federal HIV funding provided to state and local jurisdictions. For a fuller accounting of such funding, see our state HIV funding tracker.

What are the EHE goals? What is the plan to meet them? And can they be met?

The goal of the EHE is to reduce new HIV infections by 75% in five years and by 90% in ten years. If successful, it is estimated that this would avert an estimated 250,000 new infections.

There are four “pillars” to the initiative that serve as a road map for achieving EHE goals:

- Diagnose: Currently, 14% of people in the United States with HIV are unaware of their infection and 40% of all new HIV infections result from someone who did not know they were HIV positive. This strategy pillar seeks to diagnose all people in the US as soon as possible after infection.

- Treat: HIV Treatment is important for optimal individual health outcomes and harnessing the benefits of “treatment as prevention”– that is when someone is virally suppressed, they cannot transmit HIV to others. This pillar aims to treat people with HIV rapidly after diagnosis to help achieve and maintain viral suppression.

- Prevent – While the rate of new HIV infections has slowed since its peak, progress has stagnated in recent years and racial disparities persist. The prevent pillar seeks to use proven prevention interventions to stop new HIV infections from occurring with a specific focus on bolstering PrEP uptake.

- Respond – The respond pillar is focused on rapidly responding to potential HIV outbreaks to disseminate prevention and treatment services as needed and in part relies on harnessing public health strategies, such as molecular surveillance.

The EHE goals are ambitious and the strategy to reach them is grounded in science, yet one model suggests that the goal of reducing new infections by 90% in ten years “is likely unachievable with the current intervention toolkit.” However, these researchers also note that while the goals may not be fully realized, HIV infections could be reduced by up to 67% with higher levels of engagement in care and increased PrEP uptake.

What is the process for determining local-level activities?

In Phase 1, the initiative focus is on areas where HIV transmission occurs most frequently or disproportionately. As such, HHS is working to provide these jurisdictions with “resources, expertise, and technology to develop and implement locally tailored EHE plans.” Locally-focused plans mean that jurisdictions can adjust their efforts to meet local cultural and epidemiological needs. For example, a jurisdiction hard hit by the opioid epidemic might make addressing this a central theme in their EHE plan, but such a focus might not be appropriate in all areas. However, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the finalization of these plans was delayed.

How does the EHE fit within the larger policy environment?

The EHE initiative, while grounded in science and public health principles, does not take place in a vacuum. The Trump Administration backed a range of policies that limit health care access (e.g. work requirements in the Medicaid program, support for non-compliant health plans, efforts to repeal the ACA, etc.), remove protections for LGBT people and other minority groups (e.g. remove gender identity and sexual orientation protections from regulations implementing the ACA, implementation of the public charge rule, etc.), and could diminish EHE’s reach and success. The Biden Administration has opposed these policies and pledged to reverse them. While in some cases, executive actions mean these policies can be revered immediately, in others, reversing or rewriting policy can take several months or longer. In fact, President Biden issued an executive order on his first full week in office, aimed at strengthening the ACA, including by reviewing and potentially amending “policies or practices that may undermine protections for people with pre-existing conditions…” Additionally, on his first day in office, President Biden signed a separate executive order building on the Supreme Court’s Bostock v. Clayton County decision, directing federal agencies to include sexual orientation and gender identity in their definition of sex, as possible. These actions could broaden access to coverage, limit noncompliant plans, and renew and expand protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity in health care.

More broadly, our recent analysis explored a range of contextual and structural factors that could mitigate or facilitate EHE progress across the jurisdictions in four areas: policy and legal, socioeconomic, service availability, and overlapping. We find substantial regional differences that may ultimately indicate uneven EHE implementation and progress over time.

What is the relationship between the EHE, the National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS), and the HIV National Strategic Plan?

The National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS) was first introduced by the Obama Administration in 2010 marking the first time US government agencies came together to develop a coordinated approach to addressing the HIV epidemic. It was updated in 2015 and a again in 2020 in the final days of the Trump

Administration, this time rebranded as “The HIV National Strategic Plan”. Prior to his inauguration, on World AIDS Day 2020, then President-elect Biden stated he would “release a new comprehensive National Strategy on HIV/AIDS” but to date details have not been revealed.

Very similar to those outlined in NHAS, the HIV National Strategic Plan lays out four main goals to 1) prevent new HIV infections 2) Improve HIV-related health outcomes of people with HIV 3) Reduce HIV-related disparities and health inequities, and 4) Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the HIV epidemic among all partners and stakeholders.

The Strategic Plan explains, that “The HIV Plan and the Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America (EHE) initiative are closely aligned and complementary, with EHE serving as a leading component…The EHE initiative is beginning in the jurisdictions now hardest hit by the epidemic. The HIV Plan covers the entire country, has a broader focus across federal departments and agencies beyond HHS and all sectors of society…”.

What might the future hold for the EHE?

There are substantial unknowns around whether the EHE goals can be met and how effective the initiative will be in the short and long term. It is also not clear whether or not the Biden administration will seek to make changes to this initiative but leadership has signaled it will continue. Some key questions include:

- Will the Biden administration continue with the EHE and if so, will it do so in its current form? While the approach of the EHE is grounded in science and has had the support of a range of stakeholders, the Biden administration may want to make their own mark on addressing HIV. They have committed to “building upon…shared achievements and to working with established and new partners to achieve our EHE goals.” The new administration would likely want to incorporate policies that they support and that could help achieve EHE goals that the previous administration opposed such as strengthen coverage opportunities under ACA and adopting protections for individuals based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Indeed, they have stated their approach will center on equity, which is a new take on how to meet the initiative’s goals.

- Will decisions made at local levels in Phase 1 jurisdictions result in different outcomes? As noted, there are underlying contextual and structural factors within each local jurisdictions that will facilitate or mitigate EHE success so disparate outcomes across the nation could occur.

- Will current levels of funding be maintained, expanded, or decreased? The ability to meet the goals of the EHE initiative depends on funding. Congressional allocations for EHE have not matched requests from federal agencies to date and are therefore not likely enough to meet the ambitious goals the EHE sets out. It is uncertain how EHE funding will play out in the current environment but the Biden campaign said they would seek additional funding.

- How might the COVID-19 pandemic and domestic response impact the ability to meet EHE goals? While efforts to roll out EHE have continued despite the COVID-19 pandemic, implementation delays have occurred and HIV providers have faced significant challenges, including in delivering HIV treatment and prevention services. In addition, many federal employees, local health department staff, and front-line workers focused on HIV have been redeployed as infectious disease specialists to address the emerging pandemic. In recognition of these challenges, Congress appropriated additional funding for the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program and the Housing Opportunities for People with AIDS (HOPWA) program, to assist grantees in preparing for, preventing, and responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.