Introduction

LGBT adults in the U.S. are a growing population who have historically experienced health disparities. Past research shows that LGBT adults face increased challenges when it comes to mental health outcomes and access to care, experiences with serious mental health issues (particularly among trans adults), their physical health (including higher rates of disability among younger LGBT adults), and barriers to accessing and affording needed care. These negative experiences often occur at higher rates among LGBT adults who are younger, lower income, women, or report chronic illness or disability (for more detail on the demographics of LGBT adults, see Appendix). The Biden administration has issued recent executive orders aimed at combatting discrimination and disparities affecting LGBT adults, however, an increasing number of states have enacted policies seeking to restrict access to certain types of care for LGBT people, with youth access to gender affirming care being particularly impacted.

This report focuses on LGBT adults’ experiences with discrimination in their daily lives and in health care settings in addition to experiences with severe mental health crises, homelessness, well-being and stress, and experiences accessing mental health care. It also looks at the relationship between experiences with discrimination and adverse mental health outcomes, and, conversely, the importance of strong, local support networks in mitigating some of these outcomes.

These findings are based on analysis of KFF’s 2023 Racism, Discrimination, and Health Survey. A previous report from the survey focused on individuals’ experiences with racism and discrimination in health care and more broadly, and the relationship of those experiences to health and well-being.

Key Takeaways

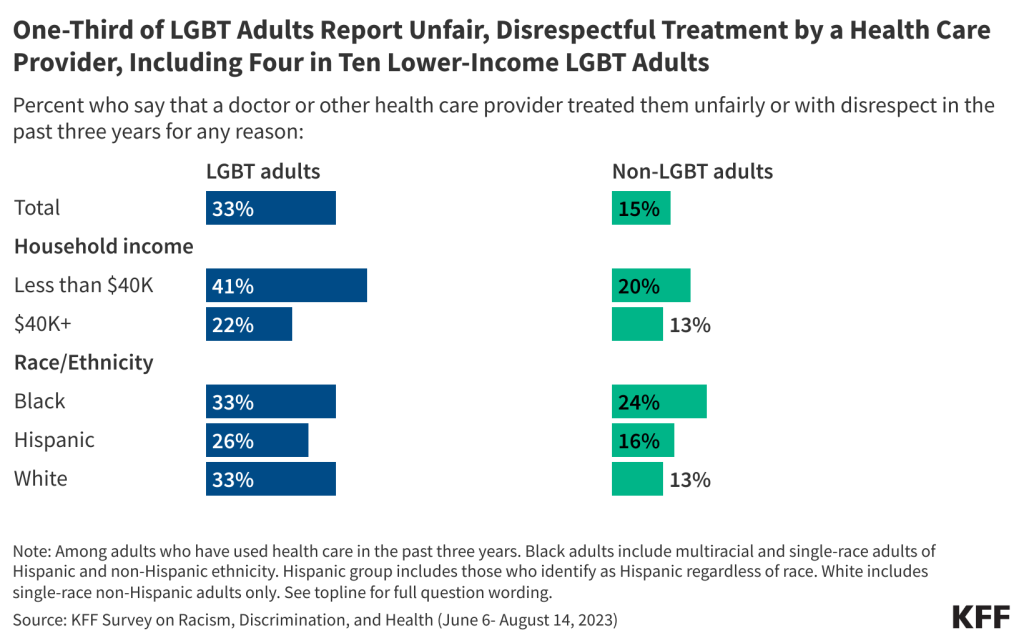

- LGBT adults face higher rates of discrimination and unfair treatment in their daily lives compared to non-LGBT adults, including in health care settings. About two-thirds (65%) of LGBT adults compared to four in ten (40%) non-LGBT adults say they experienced at least one form of discrimination in their daily life at least a few times in the past year, including receiving poorer service than others at restaurants or stores, people acting as if they are afraid of them or as if they are not smart, being threatened or harassed, or being criticized for speaking a language other than English. LGBT adults are also twice as likely as non-LGBT adults to report negative experiences while receiving health care in the last three years, including being treated unfairly or with disrespect (33% v. 15%) or having at least one of several other negative experiences with a provider (61% v. 31%), including a provider assuming something about them without asking, suggesting they were personally to blame for a health problem, ignoring a direct request or question, or refusing to prescribe needed pain medication. Our previous report from this survey showed that among adults overall, some negative experiences with health care providers were reported at higher rates among Black and Hispanic adults compared to White adults. However, among LGBT adults these experiences appear to cut across racial and ethnic groups, with White LGBT adults reporting many of these experiences at similar rates to their Black and Hispanic peers.

- LGBT adults are more likely than non-LGBT adults to report adverse consequences due to negative experiences with health care providers and to say they take steps to mitigate or prepare for unfair treatment when receiving care. Larger shares of LGBT adults compared to non-LGBT adults report having a negative health care experience in the past three years that caused their health to get worse (24% v. 9%), made them less likely to seek health care (39% v. 15%), or caused them to switch health care providers (36% v. 16%). Additionally, six in ten LGBT adults say they prepare for insults from health care providers or staff or feel that they need to be careful about their appearance to be treated fairly at least some of the time when seeking care, compared to four in ten (39%) non-LGBT adults who say the same.

- Among LGBT adults, those who are lower income, younger, and women are more likely to face challenges with discrimination or unfair treatment in their daily life and while receiving health care. For example, eight in ten LGBT adults ages 18-29 and three-quarters of LGBT women (73%) report experiencing discrimination in their daily lives at least a few times in the past year, higher than the shares reported by older LGBT adults and LGBT men. Additionally, LGBT adults with household incomes below $40,000 are more likely than those with higher incomes to say they were treated unfairly or with disrespect by a health provider (41% v. 22%) and to report at least one of several negative experiences with a doctor or health care provider in the past three years (70% v. 51%).

- Across several measures of mental health and well-being, including experiences with severe mental health crises, LGBT adults report worse outcomes compared to their non-LGBT peers. LGBT adults are more likely than non-LGBT adults to describe their own mental health as “fair” or “poor” and to report frequent worries about work, finances, politics and personal safety, as well as adverse effects of stress like problems with sleep or appetite and worsening chronic conditions. They are also twice as likely as non-LGBT adults to say they or a family member has ever experienced a severe mental health crisis that resulted in serious consequences like homelessness, hospitalization, incarceration, self-harm, or suicide (44% v. 19%). Over half of younger and lower-income LGBT adults report they or a family member experienced a severe mental health crisis.

- Experiences with discrimination exacerbate mental health challenges for LGBT adults. LGBT adults who experienced discrimination in their daily lives at least a few times in the past year are about twice as likely as those who rarely or never experienced such discrimination to say they always or often felt anxious (65% v. 34%), lonely (42% v. 15%), or depressed (38% vs. 21%) in the past year.

- For LGBT adults, having a strong local support network is a mitigating factor for experiences with severe mental health crises and regular feelings of loneliness and depression. LGBT adults who have at least a fair amount of friends and family living nearby who they can ask for help or support are less likely than those with fewer people in their support network to report experiences with severe mental health crises among themselves or a family member (54% v. 33%). In addition, LGBT adults with larger local support networks are less likely than those with just a few or no people in their support network to report regularly feeling lonely (25% v. 39%) or depressed (23% v. 40%) in the past year.

- LGBT adults – including those with fair or poor mental health – are more likely than non-LGBT adults to report going without needed mental health care, with many reporting affordability and accessibility issues of these services. Nearly half of LGBT adults (46%) say there was at time in the past three years when they needed mental health services but didn’t get them, including two-thirds (68%) of LGBT adults who describe their mental health as “fair” or “poor.” Overall, LGBT adults are more than twice as likely non-LGBT adults to say there was a time when they didn’t receive needed mental health services in the past year.

- LGBT adults are twice as likely as non-LGBT adults to report having experienced homelessness, with larger shares of Black and lower income LGBT adults reporting personal experiences with homelessness. One in five (22%) LGBT adults say they have ever experienced homelessness – twice the share of non-LGBT adults who report this. The share of LGBT adults reporting experiences with homelessness rises to four in ten among lower income LGBT adults (39%) and about one-third of Black LGBT adults (35%).

This survey’s findings underscore and enhance our understanding of the ongoing challenges LGBT adults in the U.S. face, including with respect to experiences with stigma and discrimination and poorer mental health outcomes compared to non-LGBT peers. Indeed, these findings are likely intertwined. That is, experiences of stigma and discrimination can lead to challenges with mental health, particularly at a time when LGBTQ people’s rights and access to social institutions, including health care, have been called into question and politicized. The survey finds that in several cases, these challenges are faced most profoundly by LGBT women, young people, and those with lower incomes, highlighting some groups who may benefit most from additional support and resources.

The challenges revealed in this data also identify areas where additional attention to, and policy making around, social determinants of health, provider training, non-discrimination protections, addressing stigma, and combating social isolation, could improve LGBT people’s well-being, including in terms of access to care. Federal policy making may play an especially important role in addressing discrimination and access to care, given the patchwork of access and protection at the state level.

LGBT Adults’ Experiences with Discrimination in Daily Life

About two-thirds (65%) of LGBT adults say they experienced at least one type of discrimination in their daily life at least a few times in the past year compared to four in ten (40%) non-LGBT adults. LGBT adults are consistently more likely than non-LGBT adults to report specific types of discrimination asked about on the survey, which include people acting as if they are not smart (51% v. 27%), being threatened or harassed (34% v. 12%), receiving poorer service than others in restaurants or stores (26% v. 20%), and people acting as if they are afraid of them (24% v. 11%).

Across demographics including gender, income, and age, LGBT adults are consistently more likely than non-LGBT adults to report experiencing at least one form of discrimination in their daily lives at least a few times a year. For example, seven in ten LGBT adults with household incomes below $40,000 report experiencing discrimination in their daily life at least a few times in the past year compared to about half (47%) of non-LGBT adults in the same income group. Hispanic and White LGBT adults are more likely than their non-LGBT peers to report experiencing discrimination at least a few times in the past year, while there is not a statistically significant difference in the share of Black LGBT adults and Black non-LGBT adults who report these experiences.

Among LGBT adults, women and younger adults are more likely to report experiences of discrimination than LGBT men and older LGBT adults. The share of LGBT adults who report experiencing at least one type of discrimination rises to eight in ten among those ages 18-29, compared to about half of those ages 30 and older. LGBT women are more likely than LGBT men to report experiencing discrimination in their daily life in the past year (73% v. 51%). The shares of LGBT adults reporting at least one type of discrimination in their daily lives do not differ significantly across race and ethnicity or income groups.

Black and Hispanic LGBT adults are more likely than their non-LGBT peers to say they experienced discrimination in their daily life and their race or ethnicity was a reason for these experiences. About half (51%) of Black LGBT adults and four in ten (44%) Hispanic LGBT adults say they experienced discrimination in the past year and their race or ethnicity was a reason they were treated this way compared to fewer non-LGBT Black adults (40%) and Hispanic adults (28%) who say the same. Few White LGBT adults (13%) and White non-LGBT adults (6%) report experiencing discrimination based on their race or ethnicity.

Experiences With Health Care Providers

Most LGBT adults report having positive interactions with health care providers at least most of the time. Consistent with previously reported findings among adults overall, large shares of both LGBT and non-LGBT adults who have used health care in the past three years report having positive and respectful interactions with their health care providers, with at least seven in ten saying their doctor or provider did the following at least “most of the time” during visits in the past three years: explained things in a way they could understand (81%); understood and respected their cultural values and beliefs (81%); involved them in decision making about their care (76%); and spent enough time with them during their visit (70%). A much smaller share of LGBT adults (29%) say their doctor or provider asked them about their work, housing situation, or access to food or transportation at least most of the time during visits. Among LGBT adults, consistently large shares across demographic groups report having these positive provider interactions at least most of the time in the past three years.

Despite these overall positive experiences, LGBT adults are more likely than non-LGBT adults to report unfair or disrespectful treatment by providers while receiving health care, with even larger shares among younger LGBT adults and those with lower incomes reporting these experiences. LGBT adults who have used health care in the past three years are twice as likely as non-LGBT adults (33% v. 15%) to say they were treated unfairly or with disrespect by a doctor or health care provider for any reason in the past three years. These differences hold across some demographic groups, with LGBT adults consistently more likely than non-LGBT adults to report unfair or disrespectful treatment regardless of income, gender, or age.

The shares of LGBT adults reporting unfair or disrespectful treatment include four in ten (41%) with household incomes below $40,000 who are more likely than LGBT adults with higher incomes (22%) to report unfair treatment. Among LGBT adults, those ages 18-29 are more likely than those ages 50 and over to report unfair treatment in the past three years.

Black and Hispanic LGBT adults are more likely than their White counterparts to report being treated unfairly or with disrespect by a health care provider because of their racial or ethnic background, but unfair treatment for other reasons cuts across racial and ethnic groups among LGBT adults. A quarter (24%) of Black LGBT adults and 15% of Hispanic LGBT adults who used health care in the past three years say they were treated unfairly or with disrespect by a doctor or health care provider in the past three years because of their racial or ethnic background compared to fewer White LGBT adults (4%). When adding in the shares who say they were treated unfairly for some other reason such as their gender, health insurance status, or ability to pay for care, the combined shares reporting unfair treatment for any reason are similar across Black (33%), Hispanic (26%), and White (33%) LGBT adults.

Notably, across race and ethnicity LGBT adults are more likely than their non-LGBT peers to say a doctor or health care provider treated them unfairly or with disrespect in the past three years because of something besides their race or ethnicity, including among Black adults (26% vs. 17%), Hispanic adults (23% vs. 13%), and White adults (32% vs. 11%).

In Their Own Words: Descriptions of Being Treated Unfairly or Disrespectfully by Health Care ProvidersIn open-ended responses describing instances of unfair treatment by health care providers, LGBT adults describe being interrogated about their sex lives, having their gender identity dismissed, and being ignored or disregarded.

“Despite repeatedly refusing opioids and pain medication, I was assumed to be and treated as if I was trying to scam them into providing me with drugs. When picking up my prescribed medication at a pharmacy, I was told that it was against policy to provide me with my medication, with no further reasoning provided. When I calmly asked for more explanation, they threatened to call the police. When doctors have found out about my LGBTQIA identity, they have interrogated me about my sex life repeated.” – 26-year-old LGBT adult from Virginia

“I am a transgender woman and I still have my legal name, outside of my Gender Clinic… every other doctor I’ve gone to has used my deadname and misgendered me despite me introducing myself as my chosen name and gender.” – 18-year-old LGBT adult from New York

“A male doctor was condescending about health information that I am already well-educated on and did not explain well all of the options available to me re: birth control and family planning. I also felt insulted by a comment he made about my sexual history, which may have been directed at my bisexuality.” – 23-year-old LGBT adult from Alabama

“They acted as if I wasn’t there as if I was not human.”– 38-year-old LGBT adult from Ohio

“Seemed dismissed as a person. Just received minimal care and not any respect as a person with a health issue. Felt like just a bother to their day.”– 24-year-old LGBT adult from Tennessee

In addition to general unfair and disrespectful treatment by health care providers, six in ten (61%) LGBT adults report at least one of several negative experiences with a health care provider in the last three years compared to three in ten (31%) non-LGBT adults. Regarding specific negative experiences measured in the survey, LGBT adults are twice as likely as non-LGBT adults to report that a doctor or provider assumed something about them without asking, suggested they were personally to blame for a health problem, ignored a direct request or a question they asked, or refused to prescribe needed pain medication.

Lower-income LGBT adults are more likely to report negative provider experiences. Overall, seven in ten LGBT adults with household incomes below $40,000 report at least one of these negative experience with a health care provider in the past three years compared to about half (51%) of those with higher incomes. While lower income adults overall are more likely to report at least one of these negative provider experiences, among lower income adults, LGBT adults are still about twice as likely as non-LGBT adults to report at least one of these experiences (70% v. 36%).

Many LGBT adults say negative health care experiences have had consequences on their willingness to seek care and on their physical health. LGBT adults are at least twice as likely as non-LGBT adults to report having a negative health care experience – including being treated unfairly or with disrespect, a negative provider interaction, or difficulty with language access – in the last three years that caused their health to get worse (24% v. 9%), made them less likely to seek health care (39% v. 15%), or caused them to switch health care providers (36% v. 16%).

Reflecting these negative experiences, most LGBT adults say they take steps to try to mitigate or prepare for unfair treatment during health care visits. Six in ten LGBT adults say they prepare for possible insults or feel they need to be careful about their appearance to be treated fairly at least some of the time during health care visits compared to fewer non-LGBT adults who say the same (39%). Our previous report from the Racism, Discrimination and Health Survey found that among all adults, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian and Alaska Native adults are more likely than White adults to report these experiences. This analysis finds that these experiences cut across racial and ethnic groups among LGBT adults, with similar shares of Black (63%), Hispanic (61%) and White (60%) LGBT adults saying they have to be careful about their appearance to be treated fairly or prepare for insults during visits with health care providers at least some of the time.

LGBT adults also express less comfort asking questions during health care visits compared to non-LGBT adults, which may have implications for the quality of care they receive. Half (50%) of LGBT adults who have used health care in the past three years say they have felt “very comfortable” asking doctors and other health care providers questions about their health or treatment during visits in the past three years, smaller than the share of non-LGBT adults who say the same (67%). While most LGBT adults – including similar shares across race and ethnicity, gender, income, age and coverage type – say they feel at least “somewhat comfortable” asking a doctor or provider these questions, one in eight (12%) say they feel “not very” or “not at all comfortable.”

Mental Health and Well-being Among LGBT Adults

Four in ten LGBT adults describe their mental health as “fair” or “poor,” rising to over half of younger LGBT adults and those with lower incomes. Consistent with previous surveys, LGBT adults are more likely than non-LGBT adults to describe their mental health and emotional well-being as either “fair” or “poor” (39% v. 16%). LGBT adults with household incomes below $40,000 are about twice as likely as LGBT adults with higher incomes to report fair or poor mental health (55% v. 27%), as are LGBT adults ages 18-29 compared to those ages 50 and older (56% v. 24%). Across racial and ethnic groups, about four in ten Black (40%), Hispanic (35%) and White (41%) LGBT adults describe their mental health as fair or poor.

LGBT adults report more frequent feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and depression compared to non-LGBT adults, and experiences with discrimination exacerbate these challenges for LGBT adults. Overall, about half (54%) of LGBT adults report feeling anxious either “always” or “often” in the past year, while a third report feeling lonely (33%) or depressed (32%) at least often – more than twice the shares of non-LGBT adults who report the same. Other surveys have similarly found that larger shares of LGBT people report symptoms of anxiety and depression than non-LGBT adults.

Similar to differences reported among adults overall, LGBT adults who have experienced at least one form of discrimination in their daily lives in the past year are more likely to report feeling lonely, depressed or anxious in the past year than those who rarely or never experienced discrimination in daily life. Among LGBT adults with discrimination experiences in the past year, two-thirds (65%) say they “always” or “often” felt anxious in the last 12 months, compared to about half the share of LGBT adults who rarely or never experienced discrimination (34%). LGBT adults with discrimination experience are nearly three times as likely as LGBT adults who rarely or never experience discrimination to say they felt lonely “always” “often” in the past year (42% v. 15%) and are more likely to report feeling depressed at least often in the past year (38% v. 21%). While other underlying factors beyond discrimination may contribute to these differences, the relationship between feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and depression and experiences with discrimination among LGBT adults remains significant even after controlling for other demographic characteristics including race and ethnicity, education, income, gender, and age1 . LGBT women, younger adults, and lower income adults all more likely than LGBT men, older adults and higher income adults, respectively, to report these feelings at least often in the past year.

Similar shares of LGBT adults across racial and ethnic groups report feeling any of these ways in the past year, though White LGBT adults (61%) are more likely than Black (42%) LGBT adults to report feelings of anxiety. Structural inequities and a lack of culturally sensitive screening tools may contribute to underdiagnosis and underreporting of mental illness among people of color. Underreporting of mental health issues among people of color may also be explained by diagnostic disparities among children of color whose behavior is more likely to be characterized as disruptive or criminal rather than as a mental health issue. For more information, see KFF’s issue brief on mental health and substance use disorders by race and ethnicity.

LGBT adults are more likely than non-LGBT adults to report near-daily worry and stress over several factors, such as their work, politics, their health, and the possibility of being a victim of violence. Larger shares of LGBT adults compared to non-LGBT adults say they experienced worry or stress in the past 30 days either “every day” or “almost every day” related to work or employment (45% v. 17%), politics and current events (34% v. 19%), providing for their family’s basic needs (30% v. 14%), their health (26% v. 12%), and the possibility of someone in their family being a victim of gun violence (14% v. 6%) or a victim of police violence (9% v. 4%).

Eight in ten LGBT adults report experiencing adverse effects of worry or stress in the past 30 days, over 20 percentage points higher than the share of non-LGBT adults who report this. About eight in ten (84%) LGBT adults report experiencing at least one adverse effect of worry or stress in the past month compared to about six in ten (58%) non-LGBT adults. This includes a majority who report trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or sleeping too much (72%) or poor appetite or overeating (58%). About half of LGBT adults say worry or stress has caused them to experience frequent headaches or stomachaches (47%). LGBT adults also report difficulty controlling their temper (36%), increasing their alcohol or drug use (23%), or worsening chronic conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure (16%).

The Role of Support Networks

About half of LGBT adults lack a strong local support network, but most are satisfied with the number of meaningful connections they have with other people. Social support networks can be an important resource for mental health and well-being. About half (48%) of LGBT adults say they have “a lot” or “a fair amount” of family members or friends living near them who they can ask for help or support while the other half (52%) say they have “just a few” or “none.” These shares are similar among non-LGBT adults and among LGBT adults across demographics like race and ethnicity, gender, age, and income.

While about half of LGBT adults report having few family members and friends they can ask for support, eight in ten LGBT adults say they are satisfied with the number of meaningful connections they have with other people, compared to slightly larger shares of non-LGBT adults who say the same (87%). Among LGBT adults, large shares across race and ethnicity, gender, age and income report being either “very” or “somewhat satisfied” with the number of meaningful connections they have with other people.

LGBT adults are twice as likely as non-LGBT adults to report experiences with a severe mental health crisis that resulted in serious consequences; however, having a robust local support network mitigates these challenges for LGBT adults. About four in ten (44%) LGBT adults say that they or a family member has ever experienced a severe mental health crisis that resulted in serious consequences such as homelessness, hospitalization, incarceration, self-harm or suicide – about twice the share of non-LGBT adults who report this (19%). Among LGBT adults, the share who report personal or familial experiences with a severe mental health crisis rises to over half for those with incomes under $40,000 (56%) and those ages 18-29 (55%).

LGBT adults with relatively more family and friends in their support network, however, are less likely to report experiences with severe mental health crises compared to those with fewer family and friends whom they can ask for support. One-third (33%) of LGBT adults who say they have “a lot” or “a fair amount” of family or friends living near them who they can ask for support say that they or a family member has experienced a severe mental health crisis resulting in serious consequences; however, this rises to roughly half (54%) among LGBT adults who say they have “just a few” or no family and friends whom they can ask for support. Similar shares of non-LGBT adults, regardless of the amount of family and friends in their support network, report experiences with a severe mental health crisis.

For LGBT adults, having a strong support network mitigates challenges with regular feelings of loneliness and depression. LGBT adults who say they have “a lot” or a “fair amount” of nearby family and friends they can ask for support are less likely than those with just a few or no people in their local support network to report “always” or “often” feeling lonely (25% v. 39%) or depressed (23% v. 40%) in the past year.

Access and Use of Mental Health Services

LGBT adults are more likely than non-LGBT adults to report forgoing needed mental health care, particularly among those in fair or poor mental health and younger adults. Consistent with previous surveys, about half (46%) of LGBT adults say there was a time in the past three years when they thought they might need mental health services but didn’t get them, more than twice the share of non-LGBT adults who say so (20%).

The shares who report forgoing needed mental health services rises to two-thirds (68%) among LGBT adults who describe their mental health as “fair” or “poor” and six in ten (59%) among those ages 18-29. LGBT adults with self-reported “fair” or “poor” mental health are more likely than non-LGBT adults with fair or poor mental health to report forgoing needed mental health services (68% v. 44%). Similarly, across age groups, LGBT adults are consistently more likely than their non-LGBT counterparts to say they didn’t get needed mental health care. The shares of LGBT adults who report forgoing needed mental health services in the past three years do not differ significantly across gender, income, coverage type, or race or ethnicity.

About half (46%) of LGBT adults report receiving mental health services in the past three years, about twice the share of non-LGBT adults who report receiving such services (22%). These findings are consistent with other surveys that show LGBT adults and youth are more likely than others to utilize mental health care than their peers.

Affordability and accessibility of providers are reported barriers to receiving mental health care for many LGBT adults, as is the ability to find a provider who can relate to their background and experiences. Among LGBT adults who either received or tried to receive mental health services for themselves in the past three years (55% of LGBT adults overall), roughly half say that it was difficult to find a mental health care provider who they could see in a timely manner (55%), who could relate to their background and experiences (51%), who would take their health insurance (49% among those with health insurance), or that they could afford (48%).

Among those who received or tried to receive mental health services for themselves, LGBT adults are more likely than non-LGBT adults to report having difficulty finding a mental health care provider who could see them in a timely manner (55% v. 43%) or, among those with health insurance, that would take their insurance (49% v. 34%).

Experiences with Homelessness

Housing is a core social determinant of health, meaning that housing experiences, including quality and stability, have broad impacts on health, mental health, and well-being. Housing insecurity can foster or exacerbate mental health challenges and make it more challenging to meet health needs or other social obligations. Likewise severe mental health challenges can make addressing housing needs more challenging.

Notable shares of LGBT adults, including larger shares of Black and lower-income LGBT adults – report personal experiences with homelessness, and LGBT adults are more likely than non-LGBT adults to report having been homeless. One in five (22%) LGBT adults say they have ever experienced homelessness – twice the share of non-LGBT adults who report this (11%). The share of LGBT adults reporting experiences with homelessness rises to four in ten among lower income LGBT adults (39%) and one-third of Black LGBT adults (35%). Among Black adults, those who are LGBT are more likely than non-LGBT Black adults to report having been homeless (35% v. 19%), and lower income LGBT adults are more likely than non-LGBT adults in the same income group to report experiences with homelessness (39% v. 19%).

Appendix: Demographics of LGBT adults

In this report, LGBT adults include those who identify as either lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender in a question that allows individuals to self-select as either one, multiple, or none of these options. Gender identity was measured separately from LGBT identity. Respondents could choose to describe their gender as a man, a woman, or in some other way. The LGBT men and women samples include individuals who selected that gender, including those who identify as transgender. While the sample size for LGBT individuals who selected “some other way” in the gender identity question is insufficient to report on separately, responses for these individuals are included in the total LGBT sample.

Overall, (and consistent with prior surveys) LGBT adults are younger than non-LGBT adults: about four in ten (42%) LGBT adults are between the ages of 18 and 29 compared to about one in six (16%) non-LGBT adults. LGBT adults are also more likely to have lower incomes, with about half (47%) reporting household incomes below $40,000 compared to one-third (34%) of non-LGBT adults. LGBT adults are more likely than non-LGBT adults to describe their physical health as “fair” or “poor” (26% v. 19%).

The demographics of LGBT and non-LGBT adults, however, are similar when it comes to race and ethnicity, education, and health insurance status among those under the age of 65.