Limiting Private Insurance Reimbursement to Medicare Rates Would Reduce Health Spending by About $350 Billion in 2021

Executive Summary

The cost of health care is becoming less affordable for both privately insured individuals and employers who offer health insurance coverage. Long-standing concerns about high and rising health care costs in the United States have been recently exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has increased financial pressure on many employers and individuals and led to record unemployment, furloughs and reduced wages.1 A large body of research has documented that private insurers pay higher prices than Medicare and that this gap is growing. Health care spending in the United States is nearly double the average amount spent by other high-income countries on a per-person basis without clear evidence that the overall quality of care is proportionately higher in the United States. This disparity is driven largely by higher health care prices across the United States. Reducing the prices private insurers pay for health care services could help alleviate the financial burden of health care for employers and individuals with private insurance. However, doing so would reduce revenue for hospitals and other health care providers, with uncertain effects on patient care.

In this analysis, we use data from MarketScan and FAIR Health2 to estimate the total annual reduction in health care spending by employers and privately insured individuals that would result from having private insurers reimburse hospitals and other health care providers at Medicare rates. A variety of policy levers could be used to move the health system in this direction, including Medicare for all, a public option, or regulatory controls over private prices. Our estimate illustrates the extreme of what could be accomplished in terms of reductions in spending; smaller reductions would be achieved if private sector health care prices were reduced to some multiple of current Medicare rates or if lower rates were phased in gradually. We discuss but do not model the potential effects of price reductions on the supply of services, utilization of health care services, or quality of health care. We also do not estimate the effects on tax obligations for individuals or employers, nor quantify the impact of this change on the federal budget or the Medicare program. For additional information about our approach, see the methods appendix and limitations section of this report.

With ongoing interest in proposals to address the burden of health care costs for individuals and employers—including options that align private insurance rates more closely with Medicare rates—our analysis illustrates the potentially substantial decrease in health care spending that would come from lowering private insurance rates to align more closely with Medicare levels.

Our analysis finds:

- Total health care spending for the privately insured population would be an estimated $352 billion lower in 2021 if employers and other insurers reimbursed health care providers at Medicare rates. This represents a 41% decrease from the $859 billion that is projected to be spent in 2021.

- Aggregate employer contributions toward employee premiums would decrease by about $194 billion, assuming employers’ share of premiums stays constant after private rates drop to Medicare levels.

- Employees and their dependents would spend at least $116 billion less for health care, through a combination of lower premiums and out-of-pocket spending. The reduction in federal and individual spending on health care for an estimated 19 million people in the non-group market would total $42 billion.

- Nearly half of the total reduction in spending (45%) would be for outpatient hospital services, due in part to high private rates relative to Medicare rates for outpatient care, compared to most other services. Inpatient services account for 27% of the decrease in spending, and physician office visits account for 14% of the decrease.

- Health care spending for privately insured adults ages 55 to 64 would be an estimated $115 billion lower in 2021 if private insurers used Medicare rates—this is one third of the estimated total reduction in spending. The proportion of the decrease in spending attributable to adults 55 to 64 is roughly equivalent to their share of current spending.

A detailed description of our data and methodology is discussed in the appendix of this brief. Our estimates of spending reductions are sensitive to assumptions, such as the current ratio of private-to-Medicare rates by service and market area. In addition, the estimates are sensitive to policy choices, such as whether private insurance payments should be adjusted to Medicare levels, or a higher ratio. We discuss the potential impact of these assumptions on our results in the limitations section.

Issue Brief

Introduction

The United States spends nearly twice as much as much per person on health care as comparable countries, and much of this is driven by higher prices paid by private health insurers.3 The high and rising cost of private health care has led to premiums and deductibles for employer-sponsored coverage growing faster than wages and general inflation. A large body of research has documented that private insurance pays higher prices than Medicare pays for comparable services, and that gap is growing. Between 2010 and 2018, Medicare per capita spending grew considerably more slowly than private insurance spending, increasing at an average annual rate of just 1.7% over this time period, while average annual private health insurance spending per capita grew at 3.8%.

Private Insurance Rates: Private insurance accounts for 31% of total health care spending in the United States4 and is subsidized by the federal government through the exclusion of health insurance premiums from taxable income and through ACA marketplace subsidies. High prices paid for health care services covered by private insurance lead to higher premiums and out-of-pocket costs for workers and their families with private insurance, and for employers who contribute to the cost of that coverage. Nationwide, 173 million people under age 65 had private health insurance in 2018, either from an employer plan (154 million) or the non-group market (19 million). Health expenses for employers are rising more rapidly than other prices and are consuming a growing share of total compensation. This dampens wages and may negatively impact the recovery of the job market.5

Prices paid by private insurance are largely dictated by market conditions—with providers commanding higher prices when they have more leverage in negotiations with private insurers. Provider consolidation has increased the number of markets where providers have the upper hand in these negotiations.6 While there have been some anti-trust enforcement actions in health care, health care mergers have continued and the share of health care markets with highly concentrated providers has increased.7 Increasing consolidation and rising prices for health care raise questions about whether private insurers, third party administrators and employers who offer insurance are able to control increases in health care prices.

Medicare Rates: Medicare typically reimburses hospitals and other health care providers at lower rates than private insurance. Providers generally must agree to accept the established payment rates in order to participate in Medicare, and (with the exception of a few more specialized providers, such as psychiatrists) virtually all providers are either unable or unwilling to forgo participation in Medicare. Over the years, Congress has made changes to Medicare payment systems to manage program spending and encourage providers to operate more efficiently. This has also helped to slow the growth in premiums and other costs for beneficiaries. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), an independent congressional agency, makes recommendations to Congress on Medicare payment policy, and monitors access, quality and other beneficiary issues.

MedPAC has found that “the vast majority of [Medicare] beneficiaries report being satisfied with their care, describe using an appropriate usual source of care, and report no trouble accessing timely care.”8 Compared to adults 50 to 64 with private insurance, Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older were more likely to report being very or somewhat satisfied with the overall quality of their care (87% vs 80%).9 Despite lower payment rates for physicians from Medicare than private insurance, Medicare beneficiaries are less likely than people with private insurance to report problems finding a new doctor.10 Medicare beneficiaries also report forgoing medical care at similar or lower rates than older adults (50-64) with private insurance. However, it is not clear if or how lowering private insurance reimbursement to Medicare rates would impact access and quality for people with Medicare or private insurance.

Policy Context. Over the years, federal and state lawmakers have proposed using Medicare rates to rein in health care prices. While some of this has been in the context of discussions of switching to a Medicare for all system or a public option, Medicare rates have been used in other contexts as well. Most recently, the Department of Health and Human Services specified that Medicare rates would be used to reimburse providers for care for uninsured COVID-19 patients and to set reimbursement for out-of-network COVID-19 vaccine administration.11 Washington State settled on a multiple of Medicare rates,160%, as part of a negotiated compromise in establishing a public option.12 In the state of Maryland, instead of using Medicare to set private insurance rates, the state created a Health Services Cost Review Commission that sets hospital rates for all hospital patients (regardless of insurance) according to an all-payer rate setting system. Maryland’s system also allowed the state to take steps to increase payments from all payers to hospitals to help stabilize their financial health during the COVID-19 pandemic.13 With or without a public option, legislation at the federal or state level could limit the prices health care providers charge private insurers while retaining other aspects of the private health insurance system, as in an all-payer rates setting system.

Any proposals to limit private insurance reimbursement would undoubtedly be met with fierce opposition from health care providers, since it would decrease their revenue. This phenomenon was illustrated in the recent debate over surprise medical bills when providers successfully prevented the final legislation from using Medicare rates (or a percentage of Medicare rates) as a benchmark for out-of-network reimbursement. Opponents of proposals such as Medicare for all or a public option that adopt Medicare rates argue that a broader use of Medicare rates would cause hospitals to lose money, which could lead to cost cutting that adversely affects the quality of patient care, and potentially spark the closure of some hospitals.14 The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) also has said that, in general, lowering provider reimbursement as part of a single-payer system would decrease the supply of health care.15 At the same time, analysis by MedPAC suggests that efficient providers can either cover their expenses with Medicare rates or could do so with relatively minor (2%) increases in Medicare rates for hospitals.16

In this brief, we estimate how much less individuals and employers would spend on health care if private insurance reimbursed health care providers at Medicare rates, assuming full implementation in 2021. Our analysis essentially reprices private insurance expenditures at Medicare rates; we do not make assumptions about changes in behavior or health care access or quality that could result from reduced reimbursement from private insurance. Our estimates illustrate the extreme of what could be accomplished in terms of reductions in spending. It is intended to provide a way of thinking about the effects of prices on health care spending, rather than a forecast or prediction, illustrative of the potential magnitude of savings possible from bringing private health care prices in line with Medicare. We do not estimate the impact of such a change on wages or tax obligations, nor do we model the impact on the federal budget or the Medicare program. However, we do broadly consider these issues in the limitations section of our brief. A more detailed description of the data we used and the assumptions we made are in the limitations section of this report and in the methods appendix.

Findings

Our analysis looks at the expected reduction in private health insurance spending that would occur if private insurers used Medicare rates. We estimate the aggregate reduction in spending, the aggregate reduction for employers and individuals with employer-sponsored insurance, the aggregate reduction in spending on services for those in the non-group market, the aggregate reduction by type of service and by age, and the estimated reduction in per-person spending by age group.

Total reduction in spending from using Medicare rates for people with private insurance

Health care spending would decline by more than $350 billion in 2021 if private insurance reimbursed health care providers using Medicare rates. Total spending for the approximately 173 million people under age 65 with private health insurance in our analysis is projected to reach $859 billion in 2021. At Medicare rates, total spending instead would be $507 billion (Figure 1). That $352 billion difference represents a 41% decrease in spending on care for people with private health insurance.

.Estimated reduction in spending for health care covered by employer-sponsored and private non-group health insurance

Of the 173 million people in our analysis with private insurance, 154 million have employer-sponsored coverage and spending on their care totals $757 billion (table 1 and appendix table 1). The remaining 19 million with private coverage are covered in the non-group market. Total spending for that group is about $102 billion in 2021. Full results are in the appendix.

| Table 1: Current Spending and Reduction in Spending for Employer-Sponsoredand Private Non-Group Insurance, 2021 ($ Billion) | ||||

| Number of Beneficiaries | Current Spending | Spending at Medicare Rates | Reduction in Spending if Medicare Rates Were Used | |

| Employer-sponsored insurance | 154 million | $757 billion | $447 billion | $310 billion |

| Employer share funder by premiums | $474 billion | $280 billion | $194 billion | |

| Employee share funded by premiums | $175 billion | $103 billion | $72 billion | |

| Out-of-pocket costs | $107 billion | $63 billion | $44 billion | |

| Private non-group insurance | 19 million | $102 billion | $60 billion | $42 billion |

| Total | 173 million | $859 billion | $507 billion | $352 billion |

| NOTE: Results do not include changes in administration costs or loading fees.SOURCE: KFF analysis of FAIR Health, MarketScan, American Community Survey, and National Health Expenditures data. | ||||

Total health spending for people with employer-sponsored insurance would decrease by an estimated $310 billion if private insurers used Medicare rates, assuming no change in plan design. Our analysis suggests that more than $100 billion of that reduction would be in the form of lower premiums and out-of-pocket costs paid by employees (Figure 2). In total, spending on health care for people with employer-sponsored coverage would decrease from $757 billion to an estimated $447 billion. Assuming that difference is allocated proportionately to current spending, employees would contribute an estimated $72 billion less to premiums for services paid on their behalf by insurers and spend $44 billion less on out-of-pocket costs for care covered by their insurance—for a total reduction in spending of $116 billion. Spending on services funded by employer contributions would decrease from $474 to $280 billion, a decline of $194 billion in 2021.

As discussed in greater detail in the limitations section, these estimates do not account for changes in taxable income. On the one hand, wages could decrease in the health care sector due to declines in revenue. On the other hand, wages could increase in other parts of the economy if employers pass through health savings to workers. The degree to which the health care savings are passed though would likely vary across jobs and labor markets.17 Because employer-sponsored health benefits are not taxable as income while wages are, these shifts could also affect taxes paid by employers and employees and revenues for the federal government and states.

.Spending for individuals who purchase their own insurance in the non-group market, including the ACA marketplace, would decrease by an estimated $42 billion if insurers reimbursed providers at Medicare rates—some of this reduction would come from a drop in federal spending on subsidies for people with marketplace coverage. Currently, a total of $102 billion is directly spent on health care services for the 19 million individuals with non-group insurance, including amounts paid by the federal government on behalf of the 8.5 million people who receive premium subsidies for marketplace coverage. Total spending in the non-group market would decrease to $60 billion if payments to hospitals, physicians and other providers were set at Medicare rates. Part of this reduction in spending would directly accrue to the federal government, and part to individuals, some of whom do not currently receive federal subsidies for their coverage.

Individuals who receive premium subsidies for marketplace coverage may not see their premiums decrease because premiums for benchmark plans are set as a percent of the enrollee’s income. However, enrollees with out-of-pocket expenses below the out-of-pocket maximum, as most enrollees have, would likely benefit from a lower deductible and other out-of-pocket costs. On average, the combined (medical and pharmacy) deductibles for silver and bronze plans are currently about $4,800 and $6,900, respectively.18 Combined deductibles are substantially lower—averaging about $180—for individuals from 100 to 150% of the federal poverty line who qualify for the largest reductions in cost sharing. A decrease in spending for health care services covered by non-group plans would lead to lower deductibles and copayments since each plan covers a set percentage of total costs. Costs for services that individuals pay for before they meet their deductible would also go down because the prices of the services they are buying would be lower.

Individuals who purchase their own health insurance outside of the marketplaces or who do not qualify for federal subsidies would see their premiums and out-of-pocket costs decline if Medicare rates were used. For these individuals, the federal government will not directly benefit from the lower rates because individuals themselves are paying the full premium cost. However, in some cases these individuals (including those who are self-employed) may currently deduct their health expenses from their taxes and in those cases federal tax revenue could increase if health insurance costs for those with private, non-group insurance declined.19

Reduction in spending by type of service

Almost half (45%) of the total reduction in spending, by service, would come from outpatient hospital services, if private insurance adopted Medicare rates. In total, outpatient, inpatient and emergency department care account for 69% of current spending on care covered by private insurance but would account for 78% of the reduction in spending if Medicare rates were used. Outpatient care accounts for 36% of current spending covered by private insurance, but 45% of the reduction in spending (Figure 3). Using FAIR Health’s Medicare to imputed allowed amount data and MarketScan data, we estimated that outpatient negotiated rates with private insurers are 203% of Medicare reimbursement (appendix table 2). This is a higher percentage than for most other types of services. Recently, an analysis from RAND included similar estimates of the potential reduction in spending from a switch to Medicare rates for hospital inpatient and outpatient care.20

.Our analysis used data from 2018, which is before Medicare made changes to payments for some hospital off-campus outpatient departments that lowered their reimbursement to be closer to reimbursement for physician office visits.21 By 2020, regulatory changes lowered reimbursement by 60% for the most common hospital outpatient code, hospital outpatient clinic visit.22 Since our analysis does not account for this regulatory change that occurred after 2018, our analysis likely overestimates Medicare hospital outpatient rates and thus underestimates the reduction in outpatient spending that would occur.

Reduction in spending by age

About one-third of the total reduction in spending would come from people age 55 to 64—which would amount to $115 billion less in health care spending in 2021 (Figure 4). The proportion of the decrease in spending attributable to each age group is roughly equivalent to their share of spending (see appendix table 3). Spending on individuals age 60 to 64 would be $59 billion lower if Medicare rates were used (data not shown).

.President Biden has proposed giving individuals age 60 to 64 the option of enrolling in Medicare. We did not analyze that policy but our analysis does suggest that re-pricing private health care spending for this population using Medicare rates could result in a substantial reduction in health spending overall (assuming no change in covered benefits and that all people with private insurance in that age range switch to Medicare). While the details of President Biden’s policy have not been specified, lower payment rates would likely lead to lower overall health spending for adults ages 60 to 64, but higher federal spending if costs are shifted from employers and individuals to the federal government. A full analysis of the impact of this policy is outside the scope of our paper. Such an analysis would require accounting for multiple factors, including: health insurance coverage decisions by individuals and employers; changes in the labor market and health insurance risk pools; differences between Medicare and private insurance benefit designs; and available premium and cost-sharing subsidies compared to private coverage.

Reduction in health spending, per-person

On average, per-person health care spending for those with private insurance would be an estimated $2,096 less for adults ages 19 to 64 and $1,033 less per child if Medicare rates were used. The potential reduction in per-person spending attributable to switching to Medicare rates increases steadily with age after age 3, approximately tripling from $1,387 for adults ages 19 to 35 to $3,944 among adults 55 to 64 (Figure 5). On average, per-person health care spending for adults age 19 to 64 with private insurance would be $2,096 less and per-person health care spending for children age 0 to 18 would be $1,033 less if Medicare rates were used (see appendix table 4).

.Limitations

While our analysis provides a way of thinking about the effects of prices on health care spending, this analysis is not intended to be a forecast or prediction. The direct and indirect effects would depend on the specifics of how a reduction in private sector health care prices is achieved. Our analysis is instead meant to be illustrative of the potential magnitude of savings possible from bringing private health care prices in line with Medicare.

We did not estimate the impact a reduction in aggregate health care spending would have on the labor market, employee compensation, and employers’ decisions to offer coverage. We also did not estimate how lowering health care prices would impact the market for health care services. Any changes to the prices paid for services may have other effects on health care in the United States. For example, lower reimbursement rates could decrease the number of practicing physicians or cause hospitals to contract or close. Lower reimbursement could also decrease investments in new technology. Lowering prices could also increase demand for care (particularly for those with high deductible plans). The potential combination of reduced supply and increased demand could impact access to care, health care quality and net health care spending.

While we calculated per-person declines in health care spending, we do not attempt to model the tax implications of this change, which would affect how savings are distributed between employers, employees, and the federal government and states. Increasing taxable wages would mean that individuals would not see a dollar-for-dollar increase in their after-tax income. There could also be payroll tax implications for employers if compensation shifts from tax-exempt health benefits to taxable wages. We also do not attempt to estimate the impact that shifting to Medicare rates would have on federal or state budgets. If the change led to an increase in taxable income, that would generate higher federal and state revenues. Lower payment rates would also mean lower federal spending on premium and cost sharing subsidies for marketplace coverage, and reduced health care spending for federal employees. At the same time, the reduction in private insurance reimbursement rates would likely result in lower income for some people who are employed in the health care sector, which would negatively impact tax revenues.

Further, we did not estimate the implications for Medicare and the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. An increase in taxable wages would increase payroll tax revenue. However, if these changes led to pressure to increase Medicare payment rates, higher rates could increase outlays from the Medicare Trust Fund.

Factors that impact the size of our estimates

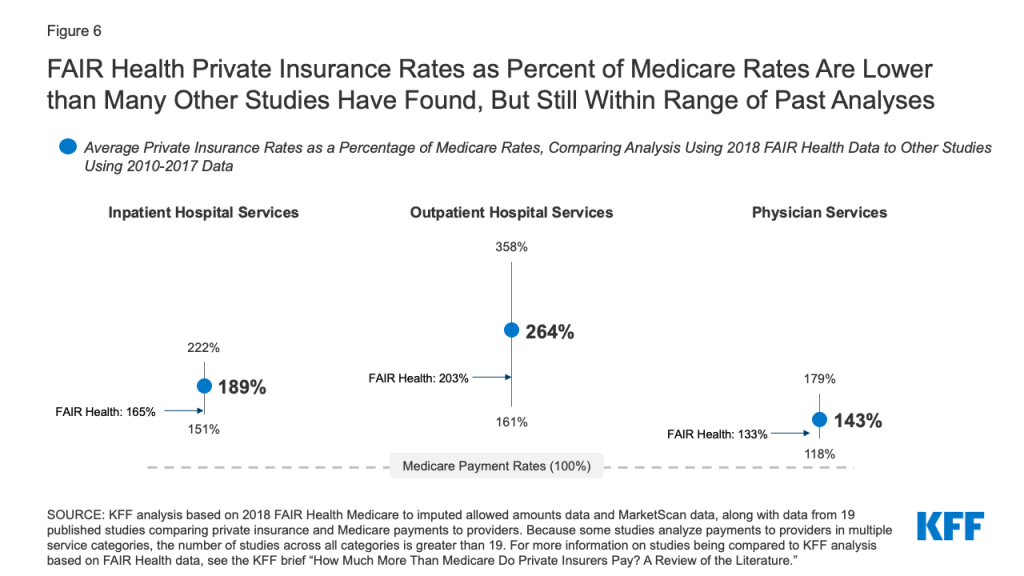

There are several factors that suggest we may have underestimated how much lower private health care spending would be if Medicare rates were used. Most significantly, we believe that the private reimbursement to Medicare ratios used in our analysis are conservative. Overall, the private insurance rates as a percentage of Medicare rates that were calculated using FAIR Health data were 165% for inpatient, 203% for outpatient and 133% for physician services (Figure 6). While these are within the range of the results of the studies in recent KFF review of the literature on private insurance payment rates compared to Medicare rates, they are each below the average among the studies. We discuss the possible reasons for this in the methods appendix.

Aside from the ratios we used to re-price health care reimbursed by private insurance, several other factors lowered our estimates of the impact of this change. As discussed earlier in this paper, we do not capture recent changes to Medicare hospital outpatient reimbursment that have reduced Medicare payments in certain instances. Our estimates also do not include savings from lower administrative costs. Assuming a constant medical loss ratio of 85%, lowering health care spending would lead to an additional $62 billion less in administrative costs (see appendix table 2). Additionally, if lower reimbursement led to a decline in the supply of care, it could negatively impact access and also further lower spending.

Conversely, several factors could lead our estimates to overstate the potential reduction in spending on health care for individuals and employers. First, if Congress increased Medicare rates after they were used to determine private insurance reimbursement, that would lead to a smaller reduction in spending than we estimate. An increase in Medicare payments to hospitals and other providers would also lead to higher Medicare spending, premiums and cost-sharing, and accelerate the depletion of the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. Additionally, our estimates did not account for how higher taxes would potentially offset some of the reduction in health spending for individuals and employers. We would expect that much of the reduction in spending on health care would eventually become taxable income—therefore individuals and employers would not reap the full benefits of this change, with some financial benefit accruing to the government instead. Additionally, if this policy change were phased in or instead used a multiple of Medicare rates (for example, 150% of Medicare rates), the estimated reduction in spending would be lower.

Our analysis also assumed that provider payment rates are the same in the non-group and large employer markets. However, due to narrower networks, non-group insurance may have lower provider payment rates than employer-sponsored coverage. Additionally, due to higher cost sharing, people with non-group coverage may have lower total health care spending than they would have if they had employer-sponsored coverage. Thus, our analysis may overestimate spending in the non-group market and also overestimate the potential to reduce spending by switching to Medicare rates.

Another more technical factor that affects the size of our estimates is that the private-to-Medicare reimbursement ratios used from FAIR Health do not factor in adjustments to Medicare reimbursements for indirect payments to hospitals such as disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, uncompensated care payments, indirect medical education payments (IME) payments. If the FAIR Health data included these Medicare payments, then the ratios of private-to-Medicare inpatient spending would be lower than the ratios used in our analysis because the Medicare reimbursement rates themselves would be higher. This would then lead to a somewhat lower estimated reduction in spending if Medicare rates were used for the privately insured. Using a MedPAC estimate that about 15% of Medicare inpatient payments are made in the form of DSH, uncompensated care and IME payments, we estimate that if those three types of payments had been factored into our analysis, it would increase private insurance inpatient reimbursement at Medicare rates by approximately $26 billion in 2021.23 However, these indirect payments serve a broader purpose in the health care system than direct payment for health care services, so it is not clear how they would be treated in a policy that sought to curtail private prices.

Discussion

As our analysis shows, policies that limit private insurance reimbursement to Medicare rates would dramatically cut health care spending, leading to lower costs for employers and individuals with health coverage from employer-sponsored or non-group insurance, including marketplace coverage. This analysis illustrates the potential for a substantial reduction in total health spending from policies like Medicare for all, a public option, lowering the age of Medicare eligibility, or all-payer rate-setting—all other things equal. At the same time, the decrease in spending would translate into a drop in revenue for hospitals, and to a lesser extent physicians and other providers.

Health care expenditures are projected to account for 18% the United States gross domestic product (GDP) in 2021. Shifting private insurance to Medicare rates would decrease this by about 1.5 percentage points, making the share of GDP spent on health care 16.5% of GDP.24 This would still be a far higher amount than comparable countries spend on health care, which ranges between 9% and 12% of GDP.

There has historically been strong resistance by hospitals and other health care providers to proposals that jeopardize their revenue, and there is every reason to suspect ongoing opposition to such policies in the future. Yet, it is not clear what the broader impact on the health care system would be. MedPAC has previously found that high reimbursement from private insurers currently reduces incentives for hospitals to operate efficiently.25 When providers operate efficiently, according to MedPAC, Medicare rates are largely sufficient or could be sufficient with relatively minor adjustments, such as a 2% increase in hospital reimbursement.26

If the reduction in hospital revenue caused some hospitals to close or limit future investments, it could negatively impact access to care and health care quality. Additionally, lower reimbursement could also negatively impact access to physicians and other health care providers. It would certainly affect physician income. However, other comparable countries spend far less than the United States does on health care per capita, and yet the United States still lags behind those countries when it comes to many measures of health outcomes, quality of care, and access to services. In all likelihood, policymakers would want to closely track the effects of this policy, and if necessary, adjust payments which would affect reductions in spending, not unlike what they have done over the years in monitoring the implementation of payment policy changes under Medicare.

At the same time, the current high prices paid for health care puts a strain on the U.S. economy—raising the cost of hiring workers with health benefits and leaving consumers with less money to spend on other goods and services. Current trends suggest that this strain is likely to worsen without policy interventions. The gap between private insurance and Medicare per enrollee spending is continuing to grow—largely due to rising health care prices.27 If health care prices and insurance premiums were to decrease, economists suggest that the resulting employer savings would lead to higher wages and increase full-time employment.28 At a time when wages for most workers have barely kept up with inflation29 and are growing slower than health costs, a reduction in health spending could lead to a meaningful improvement in economic wellbeing and could potentially increase tax revenue.

Any reduction in health care spending for people with private insurance would be very sensitive to the specifics of how the policy was developed and how Medicare rates were used. Under a Medicare for all system, payment rates might not end up being current Medicare rates, but rather some average of Medicare, Medicaid, and private rates. Likewise, it is also possible that a public option health plan would not set private insurance rates exactly at Medicare rates but instead use a multiple of Medicare rates, for example 160% of Medicare rates, as Washington State has done. Under an all-payer rate-setting system, Medicare rates or a multiple of Medicare rates could be a ceiling for reimbursement—with insurers free to negotiate discounts below that ceiling. Setting a ceiling would allow for the possibility of even greater overall savings than using the same percentage of Medicare to set all rates, because some payers might be able to negotiate lower reimbursement rates.

This approach could be phased in gradually, which would limit the magnitude of the spending reduction, while allowing policymakers to monitor and respond, if necessary, to any adverse effects on health care providers and patient care. If such a change were considered while the United States is still recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, policy makers may pay particular attention to the impact of changes to payments rates for the health care providers that are most vulnerable due to the pandemic. While health utilization plummeted early in the pandemic, overall spending has since rebounded. As of the third quarter of 2020, year-to-date health services spending was down by just 2.4% (relative to year-to-date spending as of third quarter in 2019). Additionally, in response to concerns about the loss of revenue due to the pandemic, the federal government has allocated about $150 billion in federal grants to hospitals and other health care providers of the $178 billion authorized as of February 12, 2020, along with loans and other financial assistance. However, it is not yet clear whether the pandemic will have a longer-term fiscal impact on certain hospitals and other providers.

During the pandemic, Medicare rates are being used to reimburse providers for treating the uninsured and to set reasonable rates for out-of-network COVID-19 vaccine administration.30 Broadening the use of Medicare rates to set reimbursement for private insurance would be a dramatic shift but one that could lead to substantial reduction in health care spending. With the United States economy still reeling from the impact of COVID-19, lowering private insurance reimbursement by using Medicare rates (or a multiple of Medicare rates) has the potential to put more money in the pockets of consumers and businesses. It would also help address the high and rising cost of health care for people with private insurance. Any policy debate of this magnitude would highlight the significant tradeoffs, weighing the potential reduction in health spending against strong opposition from industry stakeholders, and concerns about the potential impact on quality and access.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Appendices: Methods

To calculate the amount that would be spent on health care for people with private insurance at Medicare rates, we used ratios of 2018 Medicare reimbursement to private insurance allowed amounts calculated by FAIR Health. FAIR Health used their private health care claims dataset. FAIR Health received approximately 2 billion medical and dental claims for the 2018 year. FAIR Health calculated Medicare reimbursement rates by applying the rules of the inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS), outpatient prospective payment system (OPPS), Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS), Medicare home health prospective payment system (PPS), Medicare Inpatient Psychiatric Facility PPS, Medicare Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility PPS, Medicare Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) PPS, Medicare Ambulance Fee Schedule, Anesthesia Reimbursement Fee Schedule, Medicare Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics/Orthotics & Supplies Fee Schedule (DMEPOS), Medicare ASP Drug Pricing Files and the Clinical Laboratory fee schedule (CLAB) made available from CMS to services on claims submitted for those with private insurance. As discussed in the limitations section, FAIR Health did not include adjustments to Medicare reimbursements for indirect payments such as DSH, uncompensated care and IME. The FAIR Health ratios of Medicare reimbursement to commercial allowed amounts were calculated by metropolitan statistical area, service category, and by age group. The service categories that were used are: inpatient, outpatient, physician office, skilled nursing facility, laboratory, emergency department and urgent care center. Both facility and physician fees are included. The age groups that were used in our analysis are: 0 to 3, 4 to 18, 19 to 35, 36 to 44, 45 to 54 and 55 to 64.

As discussed in the limitations section of the report, the private-to-Medicare ratios that were used in our analysis are lower than those found in many other studies. Private insurance payment rates in those earlier studies varied based on the characteristics of the markets examined by each study and the author’s methods. Higher private payment rates were often seen in studies looking at more consolidated health care markets where providers have stronger negotiating leverage over insurers. Other factors influencing the results of the studies KFF examined were the representativeness of hospitals, physicians, and insurers used in the analysis and the data collection period, as well as differences in the services included across studies. Additionally, the FAIR Health ratios compare spending rather than prices. If people with private insurance use services more often that have relatively higher Medicare rates, then the ratio of private to Medicare spending for a set of services will be lower than the ratio of individual prices. Since our analysis focuses on spending, using ratios that compare spending rather than prices should give us a more accurate result.

The ratios from FAIR Health were then applied to 2018 spending data from IBM Health Analytics MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database (IBM Corporation). We indexed 2018 spending to the current year (2021) by applying the projected growth in spending and enrollment for those with private health insurance from the National Health Expenditures data to our estimates of 2018 spending. MarketScan is a convenience sample of health care claims provided primarily by large employers and health plans. Our analysis used claims for almost 18 million people representing about 22% of the 82 million people in the large group market in 2018. The advantage of using claims information to analyze spending is that we can look beyond plan provisions and focus on actual payment liabilities incurred by enrollees. MarketScan includes information on cost-sharing, as well as enrollees that do not have any health spending.

These data reflect out-of-pocket spending incurred under the benefit plan, but do not include balance-billing payments made to health care providers for out-of-network services or out-of-pocket payments for non-covered services. Costs for retail prescription drugs were excluded from our analysis. Our approach would not have been appropriate for prescription drug spending because there is not one Medicare price for retail prescription drugs, since those drugs are covered through the Medicare Part D program, which relies on private Part D plans that negotiate with drug manufacturers.

We reweighted the MarketScan data to represent the distribution of the entire population with private insurance. Weights were applied to match counts in the 2018 American Community Survey (ACS) for non-elderly enrollees with either employer or non-group coverage by sex, age and state. Weights were trimmed at eight times the interquartile range. In total, our analytic sample reflects a universe count of 173 million people. The ACS asks respondents about their health insurance coverage at the time of the survey. Respondents may report having more than one type of coverage; however, individuals are sorted into only one category of insurance coverage. Hospital costs were trimmed to exclude the lowest 1.5% and highest 0.5% of hospital costs within DRG. We also excluded MarketScan observations with negative spending. Due to data constraints, our analysis assumes the distribution of spending for people with private non-group insurance matches the distribution of spending for people with large group employer insurance.

To calculate what spending by private insurance would have been if Medicare rates were used instead of private insurance allowed amounts, we applied the FAIR Health ratios to total spending calculated using MarketScan within age and service category. For example, the ratio for spending on outpatient services for ages 0-3 was applied to total outpatient spending using MarketScan data for people with private insurance who are ages 0-3. We then summed spending across all age and spending categories. This approach assumes the distribution of services in MarketScan is similar to those in the FAIR Health data set on which the commercial to Medicare ratios were estimated.

We break out estimates of the reduction of spending for those that directly purchase health insurance, out-of-pocket spending for enrollees in employer plans, and the reduction in payments to providers made on behalf of enrollees in employer insurance (financed by employee and employer premium contributions). To estimate the reduction in spending attributed to services for those that directly purchase health insurance, we calculated the share of the population with private insurance in each age-sex category that was enrolled in a direct purchase plan. We multiplied the estimates of spending under current commercial rates, Medicare rates, and the reduction in savings by these shares and summed across all age and sex categories. We did not breakout out-of-pocket spending and payer spending for the direct purchase market. For those with employer insurance, we calculated out-of-pocket spending by applying the out-of-pocket share of total spending observed in the MarketScan data for each age group to the estimated spending under Medicare rates and aggregated across all groups. To estimate the share of payer spending financed by employer and employee premiums, respectively, we used MEPS data to calculate the average share of premiums covered by employer contributions (73%) and employees (27%).31

We made several simplifying assumptions to allocate the distribution of the decrease in spending among enrollee premiums and out-of-pocket spending, and employer contributions. Notably, our analysis did not account for changes in benefit design, including enrollee cost-sharing, supply of health care, or enrollment patterns if payment rates for all private insurers were set at Medicare rates. Instead, we assumed that the actuarial value of the average employer plan would stay the same if Medicare rates were used, and we used that percentage to allocate the reduction in spending across out-of-pocket costs and premiums. We also assumed that employers would keep their share of premiums constant and that the use of health care would stay the same if prices dropped.

Appendices: Tables

| Appendix Table 1: Employer and Employee Share of Current Spending, Spending Under Medicare Rates, and Potential Reduction, in $ billions 2021 | |||

| Current Spending ($B) | Spending Under Medicare Rates ($B) | Potential Reduction in Spending ($B) | |

| Employer-sponsored insurance | |||

| Total Spending on health services for enrollees in group health plans | $757 | $447 | $310 |

| Employer share of spending | $474 | $280 | $194 |

| Employee share of spending funded by premiums | $175 | $103 | $72 |

| Employee out-of-pocket spending | $107 | $63 | $44 |

| Private non-group | |||

| Total health care spending for private non-group | $102 | $60 | $42 |

| NOTES: All spending numbers are for people under 65 years old. 2021 spending is calculated by multiplying 2018 estimate by projected growth in private health insurance spending in the National Health Expenditures data.SOURCE: KFF analysis of FAIR Health, MarketScan, American Community Survey, and National Health Expenditures data. | |||

| Appendix Table 2: Current Spending for the Privately Insured, Medicare to Allowed Amount Ratio, Spending at Medicare Rates and Potential Reduction in Spending, in $ billions for 2021 | ||||

| Current Total Spending ($B) | Private Insurance Allowed Amount to Medicare Ratio | Spending Under Medicare Rates ($B) | Potential Reduction in Spending ($B) | |

| Health care services | $859 | 170% | $507 | $352 |

| Service category | ||||

| Emergency Department | $41 | 221% | $19 | $23 |

| Inpatient | $242 | 165% | $147 | $95 |

| Laboratory | $13 | 177% | $8 | $6 |

| Other | $42 | 181% | $23 | $19 |

| Outpatient | $312 | 203% | $154 | $158 |

| Physician Office | $202 | 133% | $152 | $50 |

| SNFs | $2 | 108% | $1 | $0 |

| Urgent Care | $4 | 146% | $3 | $1 |

| Administrative Costs | $152 | $89 | $62 | |

| NOTES: All spending numbers are for people under 65 years old with private health insurance coverage. 2021 spending is calculated by multiplying 2018 estimate by projected growth in private health insurance spending in the National Health Expenditures data. Administrative costs assume constant loss ratio of 85%.SOURCE: KFF analysis of FAIR Health, MarketScan, American Community Survey, and National Health Expenditures data. | ||||

| Appendix Table 3: Current Spending for the Privately Insured, Medicare to Allowed Amount Ratio, Spending at Medicare Rates and Potential Reduction in Spending, in $ Billions for 2021 | |||||||||

| Current Total Spending ($B) | Private Insurance Allowed Amount to Medicare Ratio | Total Spending Under Medicare Rates ($B) | Potential Reduction in Spending ($B) | Current OOP Spending ($B) | OOP Spending at Medicare Rates ($B) | Potential Reduction in OOP Spending ($B) | % in group plans | % in non-group plans | |

| Age group: 0-3 | |||||||||

| Female | $20 | 150% | $14 | $7 | $2 | $1 | $1 | 92% | 8% |

| Male | $25 | 152% | $17 | $9 | $3 | $2 | $1 | 92% | 8% |

| Total | $46 | 151% | $30 | $15 | $5 | $3 | $2 | 92% | 8% |

| Age group: 4-18 | |||||||||

| Female | $35 | 158% | $22 | $13 | $7 | $4 | $2 | 90% | 10% |

| Male | $37 | 158% | $24 | $14 | $7 | $4 | $2 | 90% | 10% |

| Total | $72 | 158% | $46 | $27 | $13 | $9 | $5 | 90% | 10% |

| Age group: 19-35 | |||||||||

| Female | $108 | 170% | $63 | $44 | $19 | $12 | $7 | 88% | 12% |

| Male | $54 | 172% | $31 | $23 | $10 | $6 | $4 | 88% | 12% |

| Total | $161 | 170% | $95 | $67 | $29 | $17 | $11 | 88% | 12% |

| Age group: 36-44 | |||||||||

| Female | $75 | 171% | $44 | $31 | $12 | $7 | $5 | 91% | 9% |

| Male | $43 | 172% | $25 | $18 | $7 | $4 | $3 | 91% | 9% |

| Total | $118 | 171% | $69 | $49 | $19 | $12 | $7 | 91% | 9% |

| Age group: 45-54 | |||||||||

| Female | $108 | 173% | $63 | $45 | $15 | $9 | $6 | 89% | 11% |

| Male | $81 | 174% | $47 | $34 | $11 | $6 | $4 | 90% | 10% |

| Total | $189 | 173% | $110 | $80 | $25 | $15 | $10 | 89% | 11% |

| Age group: 55-64 | |||||||||

| Female | $140 | 172% | $81 | $59 | $16 | $10 | $6 | 84% | 16% |

| Male | $132 | 173% | $76 | $56 | $14 | $8 | $5 | 86% | 14% |

| Total | $272 | 173% | $158 | $115 | $30 | $18 | $12 | 85% | 15% |

| NOTES: Analysis assumes spending is distributed across enrollees in group and non-group plans consistent with their enrollment in such plans. 2021 spending is calculated by multiplying 2018 estimate by projected growth in private health insurance spending in the National health Expenditures data.SOURCE: KFF analysis of FAIR Health, MarketScan, American Community Survey, and National Health Expenditures data. | |||||||||

| Appendix Table 4: Current Spending Per Person with Private Health Insurance, Spending Per Person at Medicare Rates and Potential Reduction in Spending Per Person, 2021 | |||

| Current Spending Per Person ($B) | Spending Per Person Under Medicare Rates ($B) | Potential Reduction in Spending Per Person ($B) | |

| Overall (0-64) | $4,973 | $2,933 | $2,040 |

| Child (0-18) | $2,932 | $1,899 | $1,033 |

| Adult (19-64) | $5,012 | $2,916 | $2,096 |

| Older Adult (60-64) | $10,353 | $5,990 | $4,363 |

| Age group: 0-3 | |||

| Female | $4,907 | $3,272 | $1,635 |

| Male | $5,788 | $3,830 | $1,958 |

| Total | $5,360 | $3,558 | $1,802 |

| Age group: 4-18 | |||

| Female | $2,275 | $1,443 | $833 |

| Male | $2,288 | $1,452 | $836 |

| Total | $2,281 | $1,447 | $834 |

| Age group: 19-35 | |||

| Female | $4,520 | $2,667 | $1,852 |

| Male | $2,215 | $1,283 | $932 |

| Total | $3,356 | $1,970 | $1,387 |

| Age group: 36-44 | |||

| Female | $5,825 | $3,400 | $2,426 |

| Male | $3,370 | $1,963 | $1,407 |

| Total | $4,612 | $2,690 | $1,922 |

| Age group: 45-54 | |||

| Female | $7,113 | $4,118 | $2,995 |

| Male | $5,608 | $3,234 | $2,373 |

| Total | $6,378 | $3,687 | $2,691 |

| Age group: 55-64 | |||

| Female | $9,282 | $5,381 | $3,901 |

| Male | $9,437 | $5,448 | $3,989 |

| Total | $9,356 | $5,413 | $3,944 |

| NOTES: 2021 spending is calculated by multiplying 2018 estimate by projected growth in per-capita private health insurance spending in the National Health Expenditures data.SOURCE: KFF analysis of FAIR Health, MarketScan, American Community Survey, and National Health Expenditures data. | |||

Endnotes

- Rakesh Kochhar “Unemployment rose higher in three months of COVID-19 than it did in two years of the Great Recession,” Pew Research, June 11, 2020; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey,” February 5, 2021; Kim Parker, Rachel Minkin, and Jesse Bennett, “Economic Fallout From COVID-19 Continues To Hit Lower-Income Americans the Hardest,” Pew Research, September 24, 2020. ↩︎

- Research for this brief is based partly upon health care claims data compiled and maintained by FAIR Health, Inc. KFF is solely responsible for the research and conclusions reflected in this brief. FAIR Health, Inc. is not responsible for any of the opinions expressed in this brief. ↩︎

- Zach Cooper, “High Prices Drive High Health Care Spending In The US, But So Too Do Other Factors: A Response To Anderson And Colleagues,” Health Affairs, January 14, 2019. ↩︎

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2019. National Health Expenditures 2018 Highlights. Washington, D.C.: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/highlights.pdf ↩︎

- Benjamin Sommers, “Who Really Pays for Health Insurance?” Int J Health Care Finance Econ 5, 89–118 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-005-6603-5; Daniel Arnold and Christopher Whaley, “Who Pays for Health Care Costs?” Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2020. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WRA621-2.html; Katherine Baicker and Amitabh Chandra, “The Labor Market Effects of Rising Health Insurance Premiums,” Journal of Labor Economics 2006 24:3, 609-634. ↩︎

- David M. Cutler and Fiona Scott Morton. “Hospitals, Market Share, and Consolidation.” JAMA vol. 310 no. 18 (November 13, 2013); Brent D. Fulton. “Health Care Market Concentration Trends In The United States: Evidence And Policy Responses.” Health Affairs 36, no. 9 (September 1, 2017): 1530–38. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0556. ↩︎

- Brent D. Fulton. “Health Care Market Concentration Trends In The United States: Evidence And Policy Responses.” Health Affairs 36, no. 9 (September 1, 2017): 1530–38. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0556. ↩︎

- MedPAC, March 2020 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 13, 2020. ↩︎

- MedPAC, March 2020 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 13, 2020. See table 4-2. ↩︎

- MedPAC, March 2020 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 13, 2020. ↩︎

- HHS, “HHS Launches COVID-19 Uninsured Program Portal,” HHS press release, April 27, 2020; 85 FR 71142. ↩︎

- Washington State Health Care Authority, “Cascade Care FAQ,” Washington State Health Care Authority, January 2020. Available at https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/cascade-care-one-pager.pdf ↩︎

- Chris L. Peterson and Dale N. Schumacher, “How Maryland’s Total Cost Of Care Model Has Helped Hospitals Manage The COVID-19 Stress Test,” Health Affairs, October 7, 2020. ↩︎

- Lane Koeing, et al, “The Impact of Medicare-X Choice on Coverage, Healthcare Use and Hospitals,” KNG Health Consulting, March 12, 2019. Available at: https://www.aha.org/system/files/2019-03/the-impact-of-medicare-X-choice-final-report-2019.pdf; Jeff Goldsmith, Jeff Leibach, and Kurt Eicher, “Medicare Expansion: A Preliminary Analysis of Hospital Financial Impacts,” Navigant. Available at: https://americashealthcarefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Navigant_Medicare-Expansion-Hospitals.pdf ↩︎

- Congressional Budget Office, “How CBO Analyzes the Costs of Proposals for Single-Payer Health Care Systems That Are Based on Medicare’s Fee-for-Service Program,” Working Paper 2020-08, December 2020. ↩︎

- MedPAC, March 2020 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 13, 2020. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar20_medpac_ch4_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0 ↩︎

- Darren Lubotsk and Craig A.Olson, “Premium copayments and the trade-off between wages and employer-provided health insurance,” Journal of Health Economics, Vol. 44, December 2015, Pages 63-79; Jeffrey Clemens and David M. Cutler, “Who pays for public employee health costs?” Journal of Health Economics, December 2014;38:65-76; Paige Qin and Michael Chernew, “Compensating wage differentials and the impact of health insurance in the public sector on wages and hours” Journal of Health Economics, December 2014;38:77-87; Jonathan T. Kolstad and Amanda E. Kowalski, “Mandate-based health reform and the labor market: Evidence from the Massachusetts reform,” Journal of Health Economics, May 2016;47:81-106; Craig A. Olson “Do Workers Accept Lower Wages in Exchange for Health Benefits?” Journal of Labor Economics, April 2002;20: S91-S114; The Incidental Economist, “Premium-wage tradeoff literature review: The public sector,” Dec. 10, 2015, available at: https://theincidentaleconomist.com/wordpress/premium-wage-tradeoff-literature-review-the-public-sector/; The Incidental Economist, “The economic theory of premium-wage tradeoffs,” April 12, 2016, Available at: https://theincidentaleconomist.com/wordpress/the-economic-theory-of-premium-wage-tradeoffs/; The Incidental Economist, “The premium-wage tradeoff in the private sector,” April 13, 2016, Available at: https://theincidentaleconomist.com/wordpress/the-premium-wage-tradeoff-in-the-private-sector/. ↩︎

- KFF, “Cost-Sharing for Plans Offered in the Federal Marketplace, 2014-2021,” Jan. 15, 2021, Available at: https://modern.kff.org/slideshow/cost-sharing-for-plans-offered-in-the-federal-marketplace/. ↩︎

- Individuals can deduct health care costs (including premiums) above 7.5% from their federal taxes. See Internal Revenue Service, “Topic No. 502 Medical and Dental Expenses,” Jan. 20, 2021, Available at: https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc502.; Individuals who are self-employed may be able to deduct their entire health insurance premium. See Internal Revenue Service, “Publication 535 (2019), Business Expenses,” March 5, 2020, Available at: https://www.irs.gov/publications/p535#en_US_2019_publink1000208843 ↩︎

- Liu, Jodi L., Zachary M. Levinson, Nabeel Shariq Qureshi, and Christopher M. Whaley, Impact of Policy Options for Reducing Hospital Prices Paid by Private Health Plans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA805-1.html. ↩︎

- This change impacted the outpatient departments that had been grandfathered from changes under the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 that switched Medicare reimbursement for new, off-campus hospital outpatient departments to rates based on the physician fee schedule, which had the impact of lowering reimbursement for those new facilities. ↩︎

- Federal Register Vol. 84, No. 218. ↩︎

- Mark Miller, “Hospital Policy Issues,” MedPAC, July 22, 2015. Testimony before House Ways and Means Committee. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/congressional-testimony/testimony-hospital-policy-issues-ways-and-means-.pdf?sfvrsn=0 ↩︎

- Calculated using Table 01 National Health Expenditures and Selected Economic Indicators, Levels and Annual Percent Change: Calendar Years 2012-2028, available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected ↩︎

- MedPAC, March 2020 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 13, 2020 (see page 61). ↩︎

- MedPAC, March 2020 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 13, 2020. ↩︎

- Health Care Costs Institute, “2018 Health Care Cost and Utilization Report,” February 2020. ↩︎

- Katherine Baicker and Amitabh Chandra, “The Labor Market Effects of Rising Health Insurance Premiums,” Journal of Labor Economics 2006 24:3, 609-634. ↩︎

- Drew Desilver, “For most U.S. workers, real wages have barely budged in decades,” Pew Research, August 7, 2018. ↩︎

- HHS, “HHS Launches COVID-19 Uninsured Program Portal,” HHS press release, April 27, 2020; 85 FR 71142. ↩︎

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Center for Financing, Access and Cost Trends, “2019 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey – Insurance Component,” Available at: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/summ_tables/insr/national/series_4/2019/ic19_iva_b.pdf. To determine the average contributions by employers and employees we summed the amounts contributed by employers and employees for single and non-single coverage for those in the private, state, and local government sector. On average employers contributed 73% of total costs and employees contributed 27%. This is slightly higher than the 72% the federal government contributes toward the most commonly chosen plans in the federal employee health benefits program. ↩︎