OBGYNs and the Provision of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care: Key Findings from a National Survey

Overview

An updated version of this report was released on June 21, 2023 and can be found here.

Introduction

Access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care in the U.S. is influenced by a variety of factors, including patients’ coverage, social determinants of health, as well as federal, state, local, and institutional level policies. We have also seen that health care providers play a large role in the care patients receive. To better understand how the provision of SRH care varies across the U.S., and how delivery of care has been influenced by changes in reproductive health policy, KFF conducted a nationally representative survey of OBGYNs across the United States. While we acknowledge that many types of clinicians are critical sources of SRH care — from midwives, to advance practice clinicians to primary care physicians— obstetrician-gynecologists (OBGYNs) comprise the largest subset of providers in this field.

This survey asked OBGYNs about a wide range of issues, including their provision of contraception, abortion, and STI care, the role of Medicaid in the delivery of SRH, screening practices for psychosocial needs, and the impact of federal and state policies on health care quality and access.

Key Findings

Contraception:

- Nearly all OBGYNs offered their patients some forms of contraceptive care, but just 18% of OBGYNs offered their patients all methods of non-permanent contraception that must be either prescribed or provided by a clinician. These methods include the pill, patch, ring, diaphragm or cervical cap, intrauterine devices (IUDs), contraceptive implants (Nexplanon), contraceptive injections (Depo-Provera) and emergency contraception (Copper IUD and Ulipristal Acetate/Ella). Those that offered all methods tended to be younger and work in large practices, with more than 10 clinicians.

- While the vast majority of OBGYNs provided both types of long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs) — IUDs (96%) and implants (84%) — only four in ten of those who provided these methods offered same-day placement. This means that at the majority of OBGYN practices, patients must make more than one visit to obtain a LARC.

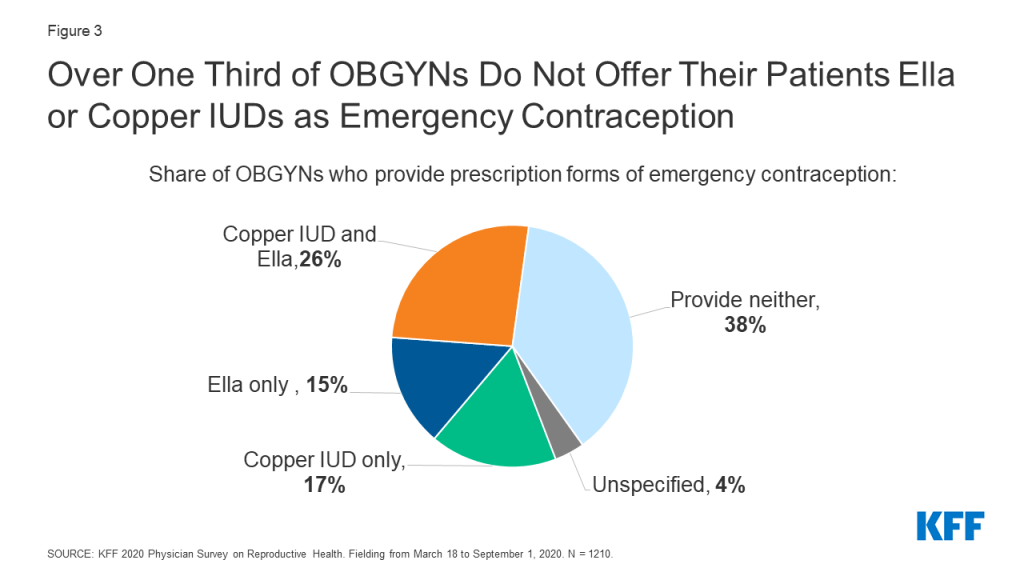

- Less than half of OBGYNs reported that they provided prescription forms of emergency contraception, which can prevent pregnancy after unprotected sex or in the event that a condom breaks. 45% provided the copper IUD and 42% provided Ella (the prescription “morning after pill”). Nearly four in ten reported that they do not provide either of these forms of emergency contraception.

Abortion:

- Most OBGYNs (75%) reported their practices did not provide abortions for pregnancy termination, but over one in five (23%) worked in practices that do. Abortion provision was more common among OBGYNs in urban and suburban locations compared to rural, and in the Northeast and West compared to the Midwest and South.

- The majority of OBGYNs who do not offer abortions refer their patients to other providers for this service, but just over one in ten (13%) neither provide nor refer for abortions. Among those who do not provide abortions, the most commonly cited reasons for not doing so included their practice having a policy against it (49%), saying that services are readily available elsewhere (45%) and personal opposition to the practice (31%). A higher share of OBGYNs in the Midwest and South cited legal regulations as a reason for not providing abortions, compared to those in the Northeast and West.

Other Sexual and Reproductive Health Services:

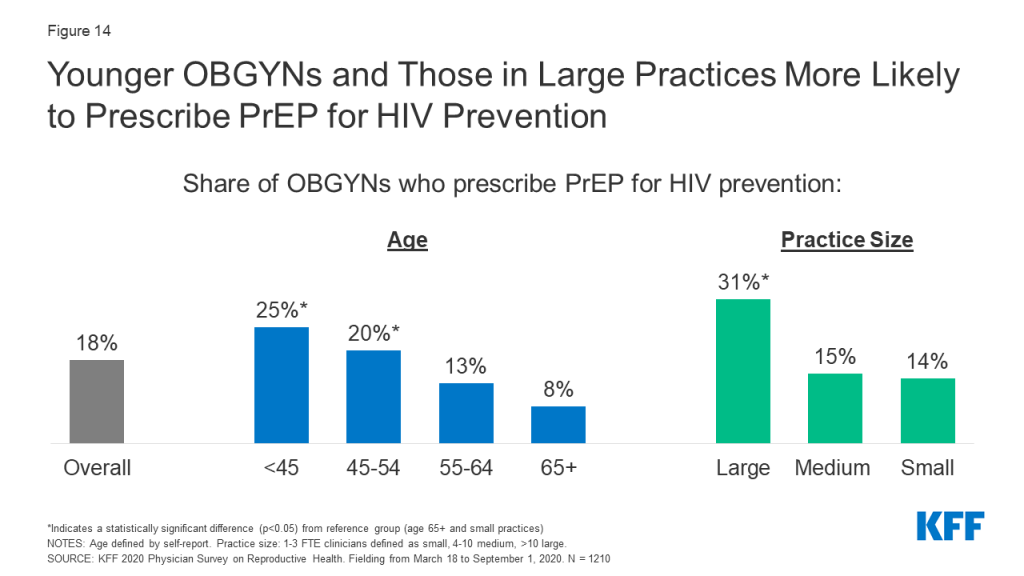

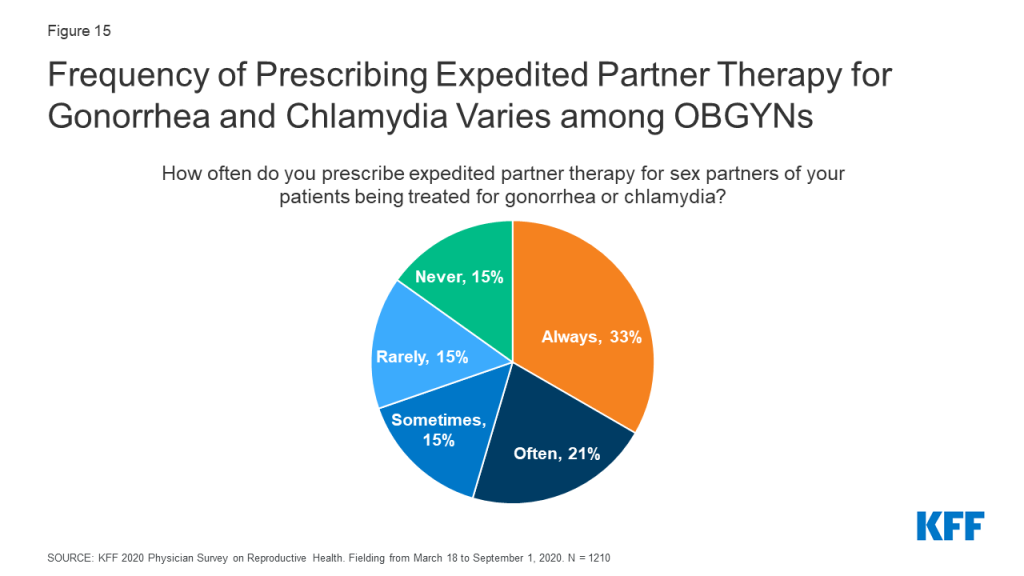

- The vast majority of OBGYNs provide onsite testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia (99%), syphilis (90%) and HIV (87%) at their practices. About half of OBGYNs said they always or often prescribe expedited partner therapy (EPT) for sex partners of patients with gonorrhea or chlamydia. Fewer than one in five (18%) prescribe pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the prevention of HIV.

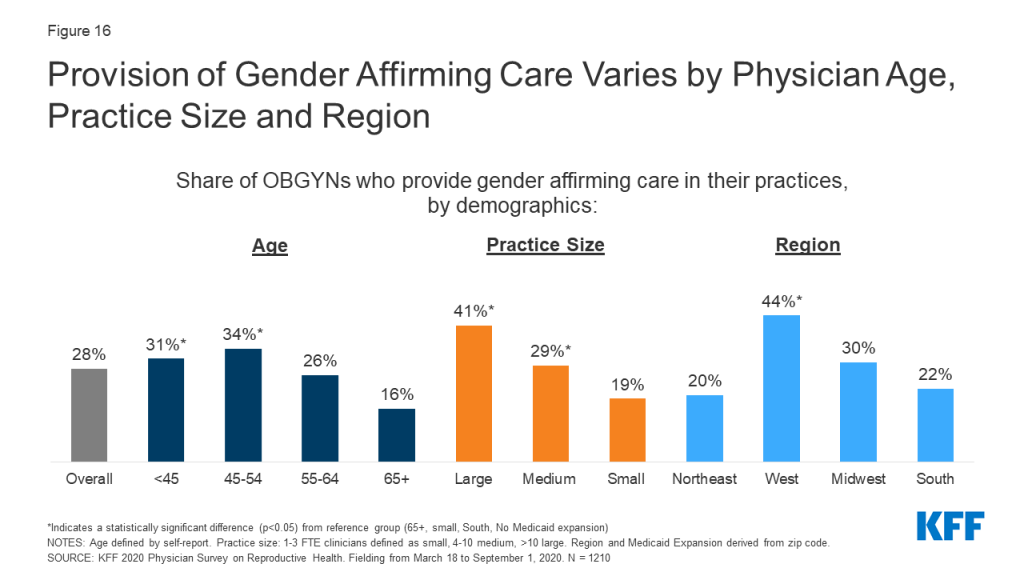

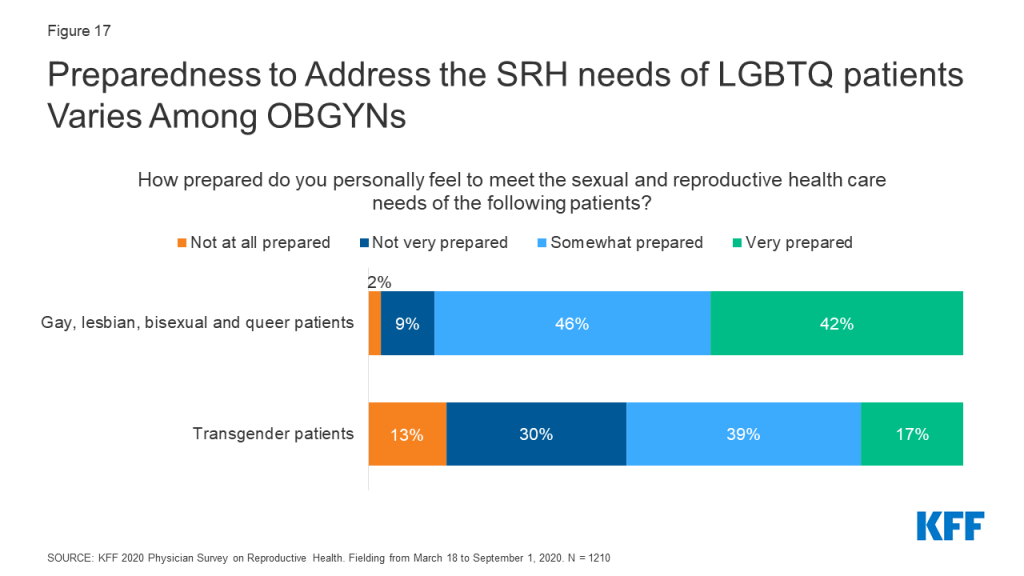

- About a quarter of OBGYNs (28%) work at practices that provide gender affirming care, including hormone therapy or gender affirming surgery. While the vast majority of OBGYNs reported they felt somewhat or very prepared to meet the SRH needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual and queer patients (88%), just over half felt the same for transgender patients (56%).

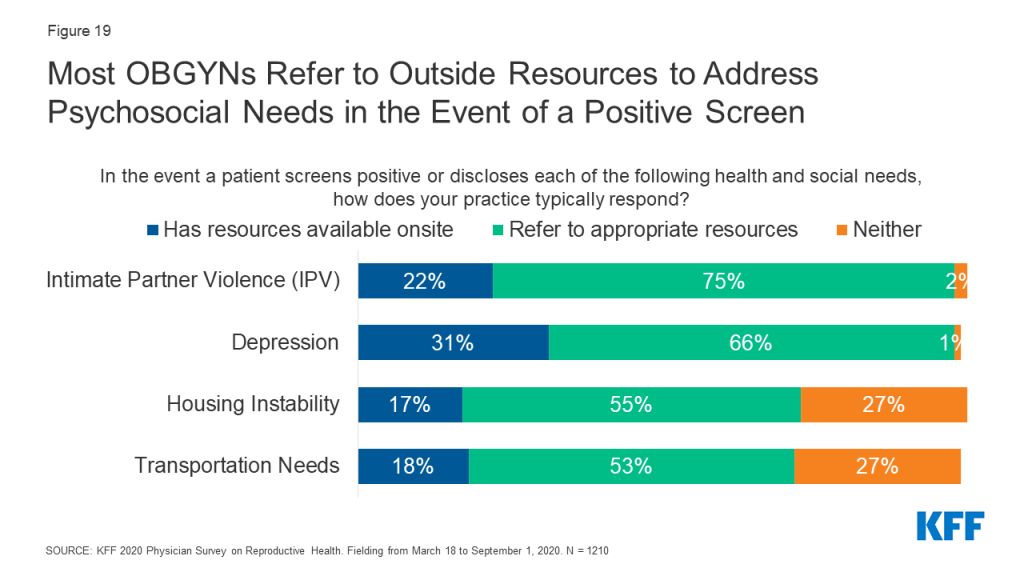

- Screening for psychosocial needs varied tremendously, with far more OBGYNs reporting they screen all patients for intimate partner violence (70%) and depression (71%) than transportation (17%) and housing (19%) needs. In the event of a positive screen, few OBGYNs said they had access to resources onsite to address these needs.

Medicaid:

- Nearly four out of five (78%) OBGYNs reported their practice accepts Medicaid. Many noted challenges associated with providing care for Medicaid patients, including difficulty finding specialists to accept referrals (73%), and being reimbursed at a lower rate than under private insurance (90%).

- A sizeable minority said they had encountered at least one Medicaid restriction regarding contraceptive care, including needing to obtain prior authorization (45%), being limited to an initial contraceptive supply of 30 days (33%), requiring “step-therapy” (15%) or being denied immediate replacement of expelled or removed LARCs (15%).

Policy Perspectives:

- Many OBGYNs are aware of the impact of out-of-pocket costs on their patients. About half of OBGYNs (53%) said the issue of affordability comes up always or often when they recommend tests or treatments to patients, and a similar share of OBGYNs (53%) said they were always or often aware of the magnitude of their patients’ out-of-pocket costs. Nearly all (92%) reported that the cost of reproductive health care poses a burden for low-income patients in their practices.

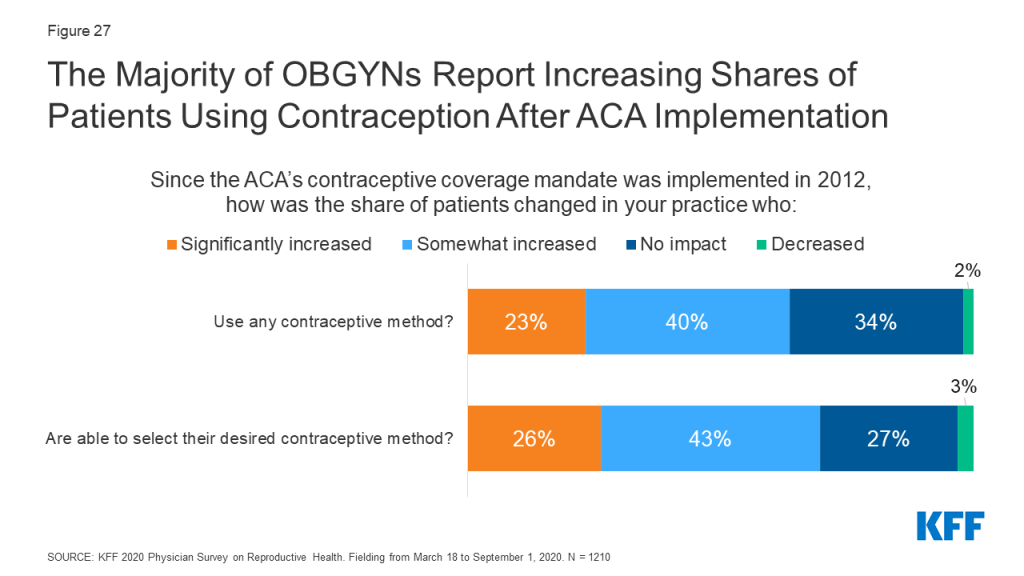

- Over six in ten OBGYNs reported an increase in the share of their patients who were using any contraceptive method (63%) as well as their desired contraceptive method (69%) since implementation of the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement in 2012.

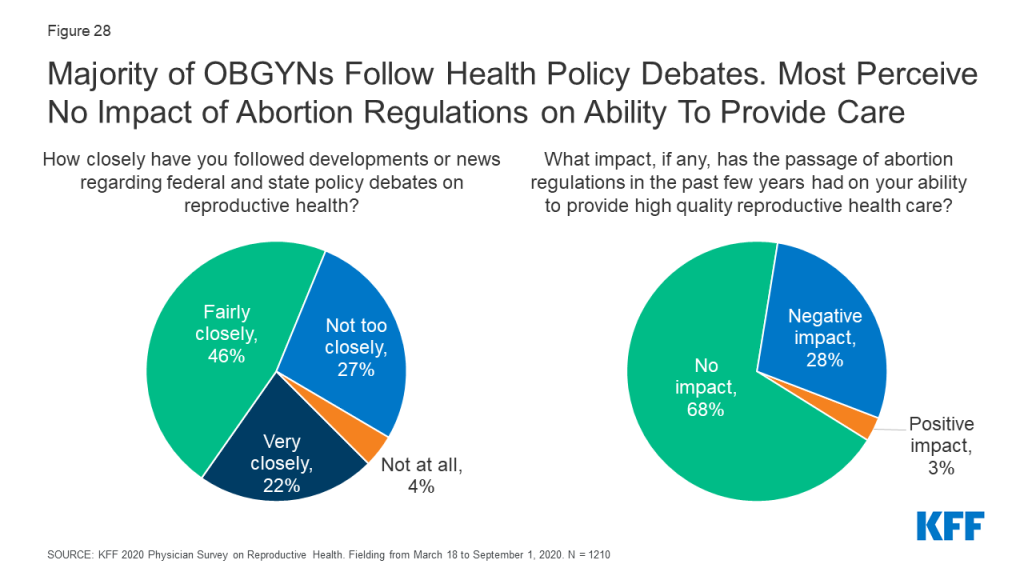

- Over one in four (28%) reported that recent state-level abortion regulations including gestational age limits and regulations of providers have had a negative impact on their ability to provide quality reproductive health care; the majority (68%), however, reported that new abortion regulations have had no impact on care. Only 3% said that they improved care.

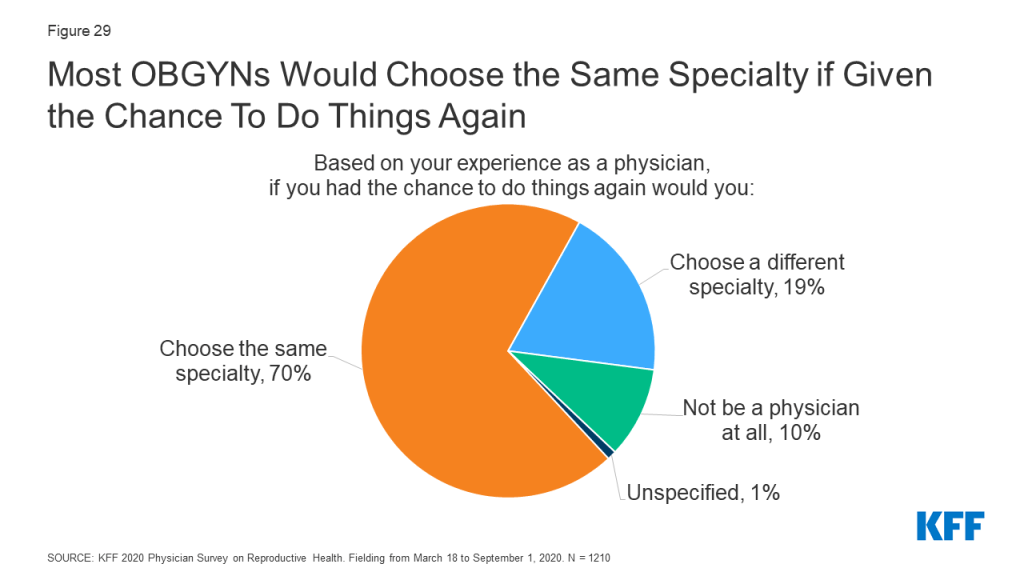

- When asked about career satisfaction, 70% of OBGYNs reported they would choose the same medical specialty, while a minority said they would choose a different specialty (19%) or not be a physician at all (10%).

Conclusions and Implications

Our findings suggest that patients may experience gaps in the availability of comprehensive SRH care provision depending on where they seek care and the providers they see. The vast majority of OBGYNs provided most forms of hormonal contraception, STI testing, cervical cancer screening, basic infertility diagnostics and prenatal care, but only a minority provided emergency contraception, abortion care, PrEP for HIV prevention, gender affirming care and resources to address psychosocial needs. This may reflect differences in training, personal preferences, and resource availability among OBGYNs.

Regional variation in SRH provision were was observed, particularly regarding the availability of same-day LARC insertions, abortion provision, and preparedness to meet the needs of LGBTQ patients. This could suggest that differences in state-level policies around SRH care, including the decision to expand Medicaid or not, may be influencing practice.

Variations in service provision were also observed by physician age. Younger physicians more often reported providing all methods of contraception, same-day LARCs, PrEP for HIV prevention, prenatal care and gender affirming care compared to the oldest group of OBGYNs.

Across several measures, a more comprehensive array of SRH services was available from OBGYNs who practiced in health centers/clinics rather than private office-based practices. While the reason for this difference is unknown based on this survey, it could perhaps reflect adherence to guidelines set out by the Health Resources & Services Administration’s Bureau of Primary Health Care Health Center Program and the Office of Population Affairs’ (OPA) Quality Family Planning Guidelines. It is notable that the vast majority of OBGYNs reported they accept Medicaid patients in their practice, and OBGYNs who served a large share of Medicaid patients had similar practice patterns compared to those who do not serve many Medicaid patients.

Most OBGYNs reported following reproductive health policy debates closely but had mixed perspectives on how health policy changes influenced their practices. For example, most OBGYNs perceived increases in the share of their patients using contraception since implementation of the ACA contraceptive coverage mandate, but a minority perceived any impact of recent abortion regulations on their ability to provide quality reproductive health care. This could be attributed to the sizable variation across the country in the adoption of abortion restrictions compared to the impact of the ACA’s contraceptive requirement that affected most women with private coverage regardless of their state of residence.

Overall, we observed heterogeneity in which SRH services OBGYNs provide, varying by both physician and practice characteristics. Gaps in SRH provision that have been highlighted from this survey warrant attention at the provider, institutional and policy level, in order to continue to strive for improved patient outcomes and experiences.

Methods Summary

Methods Summary

The 2020 KFF National Physician Survey on Reproductive Health obtained responses from a nationally representative sample of OBGYNs practicing in the United States who provide SRH care to patients in office-based settings. The survey was designed and analyzed by researchers at KFF, and an independent research company, SSRS, carried out the fieldwork and collaborated on questionnaire design, pretesting, sample design, and weighting. Survey responses were collected via paper and online questionnaires from March 18 to September 1, 2020 from 1,210 OBGYNs.

The initial sample release in March 2020 corresponded with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, after the initial sample release, a supplement of questions were added regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on providers and their practices. Among the 1,210 OBGYNs who completed the main survey, 855 OBGYNs completed the supplemental questions related to COVID-19. The full results from the COVID-19 supplemental questionnaire can be found on the KFF website here.

In this report, we present findings on issues within SRH care provision by OBGYNs, including the range of services provided (contraception, abortion, STI care), as well as the impact of payors, particularly Medicaid, on the services they offer, and how changes in reproductive health policy have impacted their practices.

The samples were weighted to match known demographics. Taking into account the design effect, the margin of sampling error for the total sample is +/- 4 percentage points at the 95% confidence level. All comparisons noted in this brief are statistically significant (p <0.05). Please see the attached topline for the full methodology report.

Sample Overview

We surveyed a nationally representative sample of 1,210 U.S. OBGYNs currently in clinical practice. Eligible physicians were board-certified OBGYNs, spent at least 60% of their time providing direct patient care, and provided sexual and reproductive health care to at least 10% of their patients in an office-based setting. We compared survey responses by key physician and practice characteristics. Gender, age and race were determined by physician self-report. For practice type, those who indicated they work in a private practice or a health maintenance organization (HMO) were classified as “private office-based,” while those who indicated they work in a community health center (e.g., FQHC, rural health center), a reproductive health care or family planning clinic (e.g., Planned Parenthood) or a government operated clinic (e.g., VA, state/county health department) were classified as “health center/clinic.” Practice size was determined by the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) physicians or advance practice clinicians (small ≤ 3, medium 4-10, large >10). Urbanicity and region were determined by the ZIP code of the practice, using U.S. Census definitions. Practicing in a Medicaid Expansion state was determined by zip code and the KFF list of states that had implemented Medicaid expansion by March 2020. OBGYNs were asked to estimate the share of patients with different insurance coverage types, including Medicaid, Medicare, private insurance, and uninsured patients.

Characteristics of Survey Respondents

Table 1 shows the demographics of the survey respondents. The majority of OBGYNs surveyed worked in private office-based practices (77% in solo, group or hospital owned private practice, 6% in HMOs and 3% in other private practices). A minority practiced in what was defined as a health center/clinic (7% in a community clinic or health center, 1% in a reproductive health care clinic, 1% in a government operated clinic, and 3% in another type of publicly-funded clinic). Half of OBGYNs worked in medium size practices with 4-10 clinicians, and the majority practiced in urban locations. OBGYNs were split fairly evenly by region, and the majority practiced in a state with Medicaid Expansion.

| Table 1: Demographics of Survey Respondents | |||

| Overall OBGYNs | N= 1,210 | ||

| Characteristic | Unweighted Distribution (%) | Weighted Distribution (%) | |

| Gender | Female | 51% | 64% |

| Male | 49% | 36% | |

| Age | <45 | 22% | 36% |

| 45-54 | 28% | 25% | |

| 55-64 | 33% | 22% | |

| 65+ | 15% | 16% | |

| Race and Ethnicity | White | 71% | 70% |

| Black | 8% | 10% | |

| Asian | 12% | 12% | |

| Other | 10% | 9% | |

| Practice type | Health Center/Clinic | 14% | 12% |

| Private Office-Based | 85% | 86% | |

| Practice size | Large (>10 FTE) | 19% | 20% |

| Medium (4-10 FTE) | 46% | 50% | |

| Small (≤ 3 FTE) | 33% | 28% | |

| Urbanicity | Urban | 55% | 59% |

| Suburban | 21% | 23% | |

| Rural | 21% | 13% | |

| Region | Northeast | 17% | 21% |

| West | 24% | 23% | |

| Midwest | 23% | 20% | |

| South | 37% | 35% | |

| Medicaid Expansion State | Yes | 66% | 68% |

| No | 34% | 32% | |

| Share of Medicaid Patients | ≥ 25% | 47% | 45% |

| <25% | 51% | 53% | |

| A small percentage of respondents left demographic questions blank or their responses were unspecified, including unweighted n= 3 (0.2%) for gender, 18 (1%) for age, 14 (1%) for practice type, 26 (2%) for practice size, 35 (3%) for urbanicity, and 16 (1%) for share of Medicaid patients.NOTES: Gender, age, race and share of Medicaid patients defined by self-report. Practice type was also based on self-report: private office-based = private practice/HMO, health center/clinic = community health center/reproductive health care clinic/government operated clinic. Practice size defined by number of full-time equivalent physicians and advance practice clinicians that physicians reported in their practice (small ≤3 FTE, medium 4-10, large >10). Urbanicity, region and Medicaid Expansion state derived from zip-code.SOURCE: KFF 2020 Physician Survey on Reproductive Health. Fielding from March 18 to September 1, 2020. N = 1210 | |||

Report: Clinical Care

An updated version of this report was released on June 21, 2023 and can be found here.

Contraception

Provision of Contraception

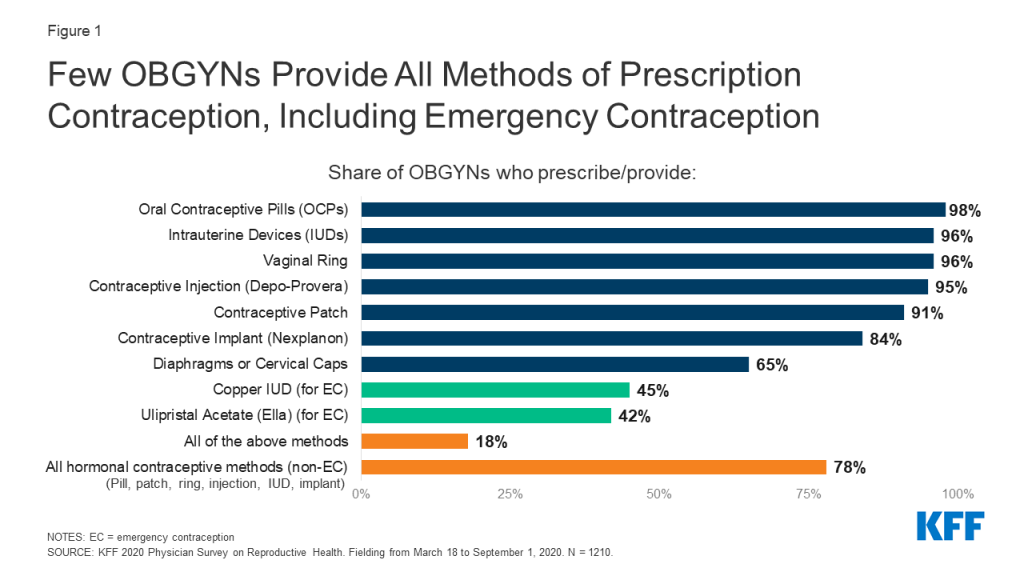

The vast majority of OBGYNs prescribe/provide oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) (98%), intrauterine devices (IUDs) (96%), vaginal rings (96%), contraceptive injections (Depo-provera) (95%), and the patch (91%). Slightly fewer provide contraceptive implants (Nexplanon) (84%); of note, providers must complete a 2-hour live training from the manufacturer in order to provide Nexplanon, which may serve as a hurdle to some in delivering this method of contraception. Notably fewer OBGYNs provide diaphragms or cervical caps (65%) than other methods of non-emergency contraceptives (Figure 1).

The majority of OBGYNs (78%) provided all hormonal methods of contraception, including the contraceptive pill, patch, ring, injection, IUD and implant (Figure 1). Fewer (54%) provided all hormonal methods, plus diaphragms or cervical caps as a barrier method. About half (51%) provided all hormonal methods, plus at least one form of prescription emergency contraception, either the copper IUD or ulipristal acetate/Ella. Just 18% of OBGYNs reported prescribing all nine of the contraceptive methods asked about, including all hormonal methods (pill, patch, ring, injection, IUD and implant), a barrier method (diaphragm or cervical cap) and both methods of prescription emergency contraception (copper IUD and ulipristal acetate/Ella).

A higher share of OBGYNs who are female compared to male, younger compared to older, and work in large practices compared to small reported providing all methods of contraception (Table 2).

| Table 2: Characteristics of OBGYNs who Provide All Methods of Contraception | ||

| Characteristic | Share of OBGYNs who Provide all Methods of Contraception | |

| Overall | 18% | |

| Gender | Female | 21* |

| Male | 12 | |

| Age | <45 | 28* |

| 45-54 | 19* | |

| 55-64 | 13* | |

| 65+ | 5 | |

| Practice Size | Large | 24* |

| Medium | 19 | |

| Small | 13 | |

| *Indicates a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) from reference group in boldNOTES: “All methods contraception” defined as providing/prescribing hormonal contraceptive pills, patch, ring, diaphragm or cervical caps, IUDs, implants, injectables and emergency contraception (Copper IUD and Ulipristal Acetate/Ella). Gender and age defined by physician self-report. Practice size defined by number of full-time equivalent physicians and advance practice clinicians (small ≤3 FTE, medium 4-10, large >10).SOURCE: KFF 2020 Physician Survey on Reproductive Health. Fielding from March 18 to September 1, 2020. N = 1210 | ||

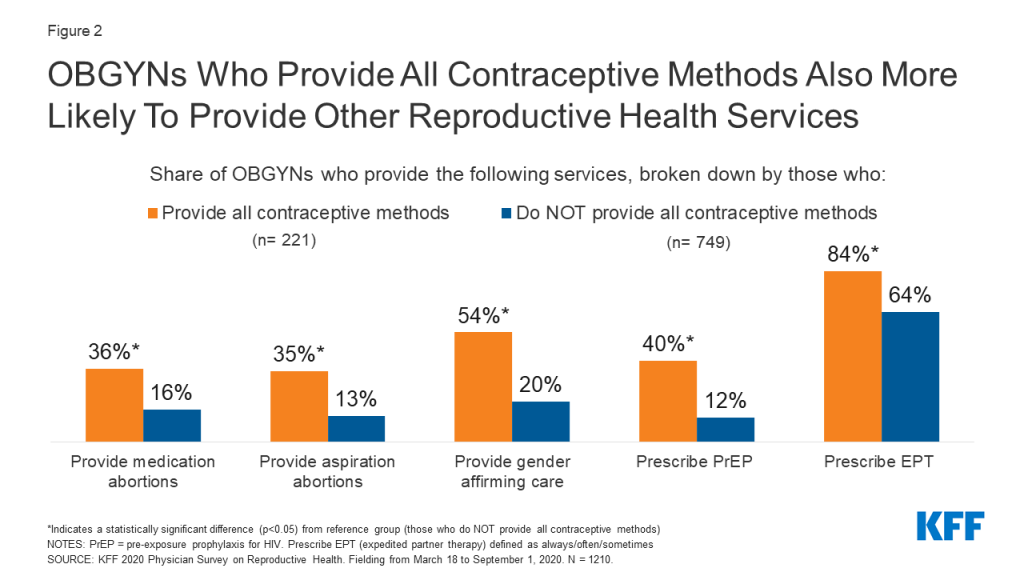

Provision of other SRH services seemed to cluster among OBGYNs who provided all contraceptive methods. For example, OBGYNs who provided all methods of contraception were more likely to provide abortions, gender affirming care, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV and expedited partner therapy (EPT) for gonorrhea and chlamydia compared to OBGYNs who do not provide all methods of contraception (Figure 2).

Provision of Emergency Contraception

Among the three commonly used methods of emergency contraception (EC), the copper IUD and ulipristal acetate (Ella) must be prescribed, and levonorgestrel (Plan B) can be purchased over the counter. For the two methods that must be prescribed/provided by a clinician, fewer than half of OBGYNs provided copper IUDs (45%) and Ella (42%) as forms of emergency contraception (Figure 1); 38% provided neither, 26% provided both methods, 17% provided the copper IUD only and 15% provided Ella only (Figure 3).

A higher share of female OBGYNs provided copper IUDs and Ella compared to male OBGYNs, as did younger OBGYNs (age <55) compared to older OBGYNs (age 65+). Geographically, a higher percentage of OBGYNS in the Northeast and West offered copper IUDs and Ella for emergency contraception compared to the South, as did OBGYNs in states that have expanded Medicaid compared to those that have not. A larger share of abortion providers offered the copper IUD as EC and Ella compared to non-abortion providers (Table 3).

| Table 3: Emergency Contraception (EC) Provision | |||

| Characteristic | Provides following forms of EC: | ||

| Copper IUD | Ulipristal Acetate (Ella) | ||

| Overall | 45% | 42% | |

| Gender | Female | 51* | 46* |

| Male | 33 | 36 | |

| Age | <45 | 65* | 51* |

| 45-54 | 45* | 43* | |

| 55-64 | 29 | 37 | |

| 65+ | 22 | 30 | |

| Region | Northeast | 47* | 47* |

| West | 58* | 55* | |

| Midwest | 47* | 40 | |

| South | 34 | 32 | |

| Practice in Medicaid Expansion State | Yes | 52* | 47* |

| No | 30 | 32 | |

| Provide Abortions | Yes | 59* | 61* |

| No | 42 | 37 | |

| *Indicates statistically significant difference (p<0.05) from reference group in boldNOTES: Gender, age and provides abortions defined by self-report. Region and Medicaid Expansion derived from zip code.SOURCE: KFF 2020 Physician Survey on Reproductive Health. Fielding from March 18 to September 1, 2020. N = 1210 | |||

Considerations for LARCs and injectables

The majority of OBGYNs (84%) reported they provide both types of LARCs (IUDs and implants) and 11% provided just one type. However, among those who provide IUDs and implants respectively, only about two in five provided same-day placement for IUDs (40%) and implants (39%). This means that at the majority of OBGYN practices, patients must make more than one trip to the clinic to obtain a LARC.

Provision of same-day LARCs was more common among OBGYNs who are younger, work in health centers/clinics, in large practices, and outside the South (Table 4). Additionally, a larger share of OBGYNs who provided all methods of contraception offered same-day IUD (64% vs. 33%) and implant (62% vs. 32%) insertions compared to those who did not offer all contraceptive methods. A higher percentage of abortion providers provided same-day IUD (56% vs. 36%) and implant (54% vs. 35%) insertions compared to non-abortion providers, which may be important for some patients as part of post-abortion care.

| Table 4: Provision of same-day LARCs, by demographics | |||

| Characteristic | Provides same-day placement of: | ||

| IUDs | Implants | ||

| Overall | 40% | 39% | |

| Age | <45 | 44* | 45* |

| 45-54 | 46* | 41 | |

| 55-64 | 36 | 35 | |

| 65+ | 27 | 28 | |

| Practice type | Health center/clinic | 62* | 61* |

| Private office-based | 37 | 36 | |

| Practice size | Large | 61* | 60* |

| Medium | 39* | 36 | |

| Small | 28 | 29 | |

| Region | Northeast | 43* | 41 |

| West | 49* | 49* | |

| Midwest | 43* | 45* | |

| South | 30 | 29 | |

| *Indicates statistically significant difference (p<0.05) from reference group in boldNOTES: Age defined by self-report. Private office-based = private practice or HMO, Health center/clinic = community health center/reproductive health care clinic/government operated clinic. Practice size: 1-3 FTE clinicians small, 4-10 medium, >10 large. Region derived from zip code.SOURCE: KFF 2020 Physician Survey on Reproductive Health. Fielding from March 18 to September 1, 2020. N = 1210 | |||

Insurance restrictions and requirements around prior authorization for contraception likely play a role in whether or not providers offer same-day LARCs. We asked OBGYNs whether the Medicaid plan they bill most often required them to obtain prior authorization for specific contraceptives; a higher share of those who had not been required to obtain prior authorization for contraceptives provided same day placement of IUDs (52% vs. 31%) and implants (52% vs. 32%) compared to OBGYNs that reported prior authorization had been required.

Beyond insurance hurdles, practices may not offer same-day LARC insertion if they do not have the contraceptive methods stocked onsite. Among those that provide IUDs, four in five (79%) stock IUDs onsite; nearly three in four implant providers (73%) stock implants onsite; and about half (51%) of OBGYNs who provide injectables stock them on site. Stocking these contraceptive methods onsite was more common among OBGYNs in health centers/clinics than private office-based practices, in large and medium size practices rather than small, and among OBGYNs who provide all methods of contraception compared to those who do not (Table 5).

Additionally, a larger share of OBGYNs who reported prior authorization was not required for specific contraceptives stocked IUDs (90% vs. 75%) and implants (87% vs. 65%) compared to OBGYNs who reported prior authorization was required for specific contraceptives. This suggests that requirements around prior authorization could play a role limiting the availability of same-day LARC insertion.

| Table 5: Stocking Contraceptive Methods Onsite Varies by Practice Characteristics | ||||

| Characteristic | Among OBGYNs who provide these methods of contraception, share who stock: | |||

| IUDs | Implants | Injectables | ||

| Overall | 79% | 73% | 51% | |

| Practice type | Health center/clinic | 92* | 93* | 84* |

| Private office-based | 77 | 69 | 46 | |

| Practice size | Large | 94* | 89* | 72* |

| Medium | 83* | 73* | 50* | |

| Small | 62 | 58 | 38 | |

| Provides All Methods of Contraception | Yes | 94* | 91* | 74* |

| No | 74 | 67 | 45 | |

| *Statistically significant difference from reference group in boldNOTES: Practice type: Private office-based = private practice or HMO, Health center/clinic = community health center/reproductive health care clinic/government operated clinic. Practice size: 1-3 FTE clinicians small, 4-10 medium, >10 large. Medicaid Expansion derived from zip code. All contraception = pill, patch, ring, IUD, implant, injection, diaphragm, Copper IUD and Ella for ECSOURCE: KFF 2020 Physician Survey on Reproductive Health. Fielding from March 18 to September 1, 2020. N = 1210. | ||||

Fertility Awareness-Based Methods

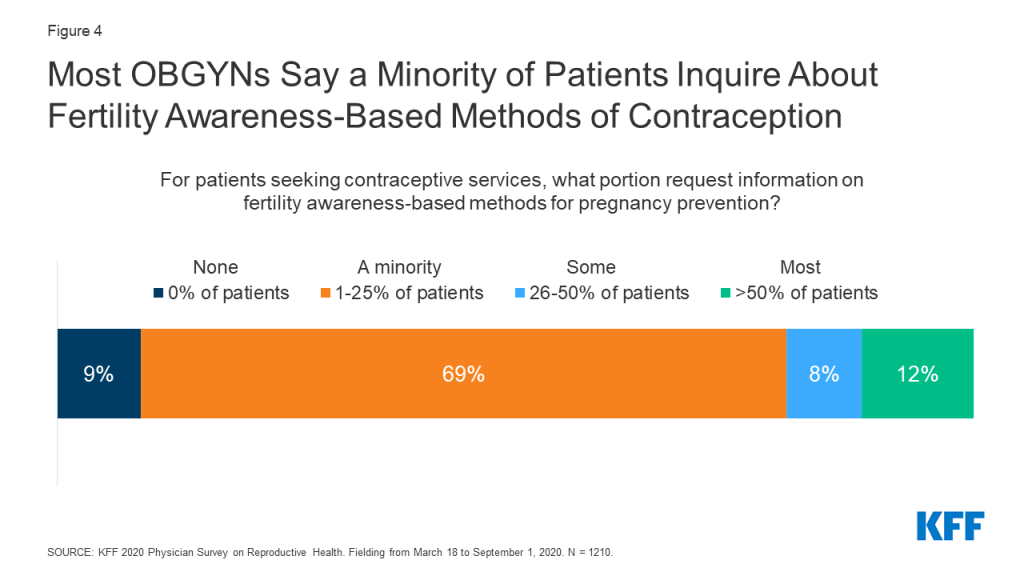

Under the Trump Administration, there was increased federal support for and attention to fertility awareness-based methods (FABM) of contraception – that is tracking ovulation. This includes instruction on monitoring basal body temperature, cervical mucus, hormone production, cervical position, and calendar tracking. For patients seeking contraceptive services, most OBGYNs reported that a minority of patients request information on FABM. More than three fourths (78%) of OBGYNs said less than a quarter of patients requested this information (Figure 4).

Abortion

Abortion provision by U.S. OBGYNs

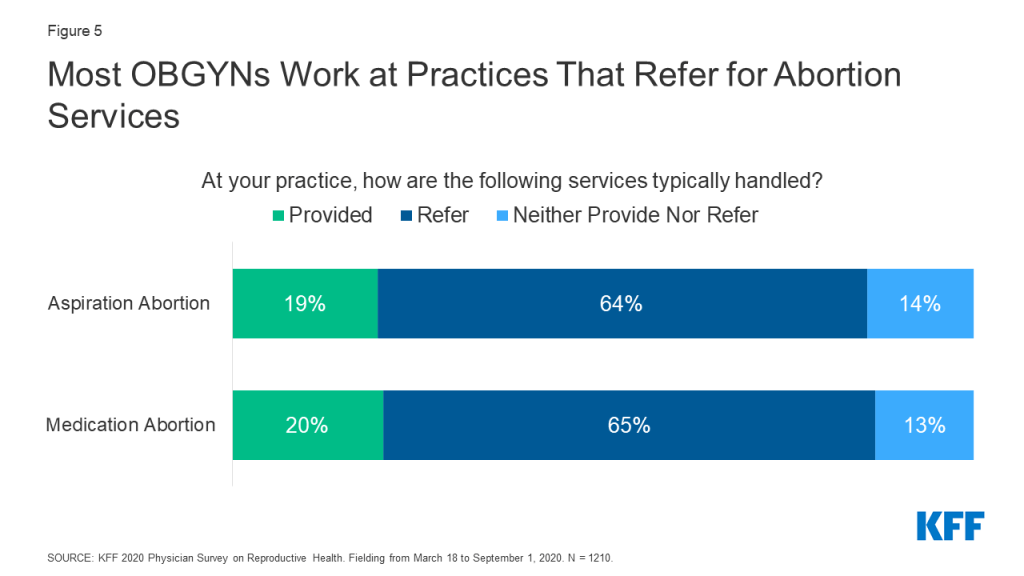

One in five OBGYNs said their practice provides medication abortions (20%) and aspiration abortions (19%), but the majority of OBGYNs did not provide abortions for pregnancy termination in their practices. Nearly two-thirds referred patients to outside providers for these services, and a minority neither provided nor referred for these services (Figure 5). These data are fairly consistent with prior estimates of abortion provision in the U.S. (Stulberg et al. 2012, Grossman et al. 2019).

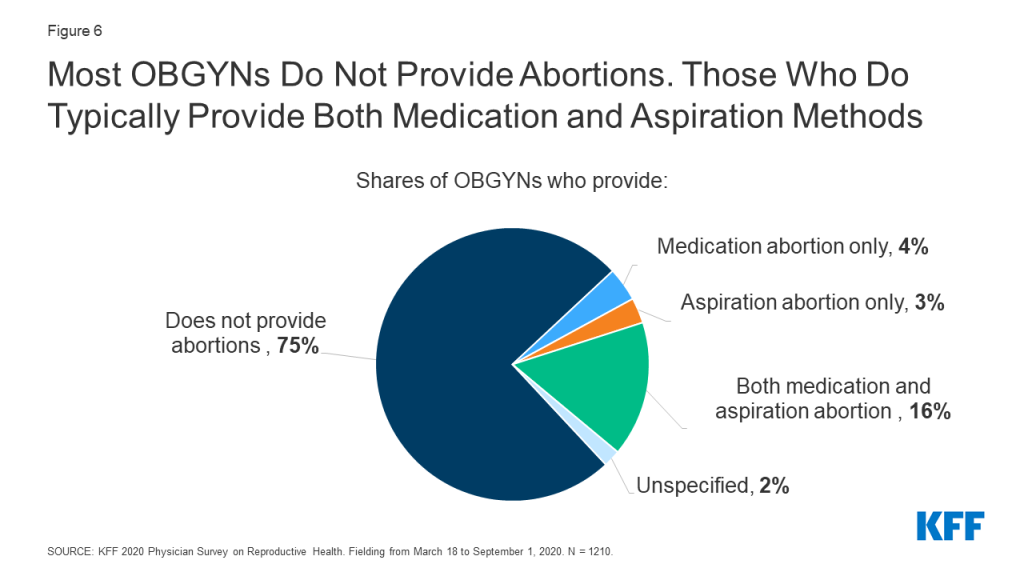

While 75% of OBGYNs surveyed did not provide abortions within their practices, 23% provided at least one type of abortion; 16% offered both medication and aspiration abortions in their practices, 4% provided medication abortions only and 3% provided aspiration abortions only (Figure 6). Among abortion providers, seven in ten (71%) provided both medication and aspiration abortions, suggesting that most OBGYNs who choose to provide abortions offer more than one method of pregnancy termination. Having this option is important to many people seeking abortion care, who may prefer one method over another.

Characteristics of OBGYNs who provide abortions

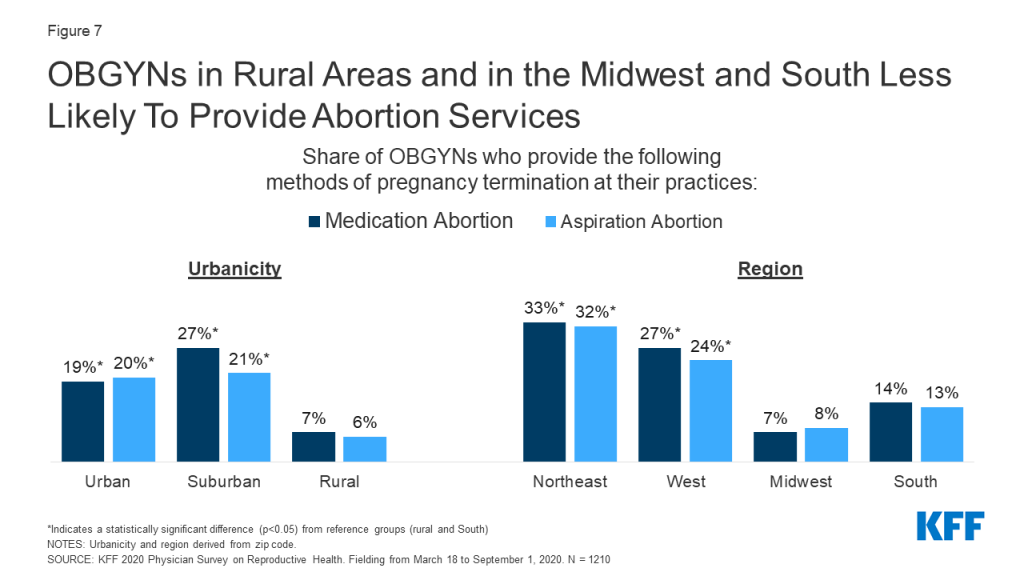

The provision of abortion services varied by region and urbanicity. A larger percentage of OBGYNs in urban and suburban locations than those in rural locations provided medication and aspiration abortions, while a larger share of OBGYNs in the Northeast and West reported providing both types of abortions compared to OBGYNs in the Midwest and South (Figure 7). Similar trends by urbanicity and region were found by Stulberg et al. in their 2008 survey of U.S. OBGYNs.

Additionally, a higher share of the youngest group of OBGYNs, age <45, provided medication abortions within their practices compared to older physicians, age 65+. More OBGYNs at large practices offered aspiration abortions than those at medium and small practices. No differences were seen by practice size for medication abortions (Table 6).

| Table 6: Abortion Provision Varies by Physician and Practice Characteristics | |||

| Share of OBGYNs who provide: | |||

| Medication abortions | Aspiration abortions | ||

| Overall | 20% | 19% | |

| Age | <45 | 25* | 22 |

| 45-54 | 22 | 20 | |

| 55-64 | 14 | 15 | |

| 65+ | 13 | 14 | |

| Practice type | Health Centers/Clinics | 23 | 22 |

| Private Office-Based | 19 | 18 | |

| Practice Size | Large | 23 | 27* |

| Medium | 21 | 18 | |

| Small | 15 | 15 | |

| Urbanicity | Urban | 19* | 20* |

| Suburban | 27* | 21* | |

| Rural | 7 | 6 | |

| Region | Northeast | 33* | 32* |

| West | 27* | 24* | |

| Midwest | 7 | 8 | |

| South | 14 | 13 | |

| *Statistically significant difference (p<0.05) from reference group in boldNOTES: Age defined by self-report. Practice type: private = private practice/HMO, public = community health center/reproductive health care clinic/government operated clinic. Practice size defined by number of full-time equivalent physicians and advance practice clinicians (small ≤3 FTE, medium 4-10, large >10). Urbanicity and region derived from zip-code.SOURCE: KFF 2020 Physician Survey on Reproductive Health. Fielding from March 18 to September 1, 2020. N = 1210 | |||

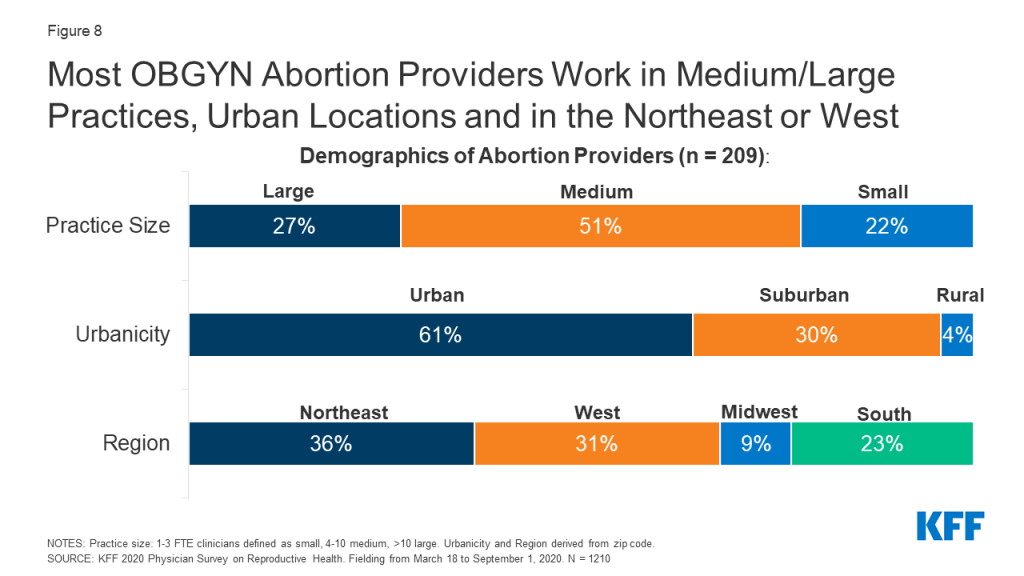

Among abortion providers, similar demographic patterns held true. The majority of abortion providers worked in medium or large size practices compared to small. Six in ten abortion providers worked in urban areas, three in ten in suburban areas and just 4% in rural practices. Approximately one-third of OBGYNs who work in practices providing abortions were in the Northeast (36%), another third in the West (31%), with much fewer in the more conservative Midwest (9%) and Southern (23%) regions (Figure 8). These findings are consistent with prior research by Stulberg et al. that found abortion provision is clustered in urban areas and scarce in the Midwest and South.

When looking at practice type, the share of OBGYNs who provided medication and aspiration abortions did not differ between health centers/clinics and private office-based practices (Table 6). However, a smaller share of those in health centers/clinics referred for both medication (51% vs. 66%) and aspiration abortions (51% vs. 66%) compared to those in private office-based practice; for health centers/clinics participating in the Title X Family Planning program, fewer referrals may be due to changes to the program regulations which did not permit Title X recipients to refer patients for abortions at the time the survey was fielded.

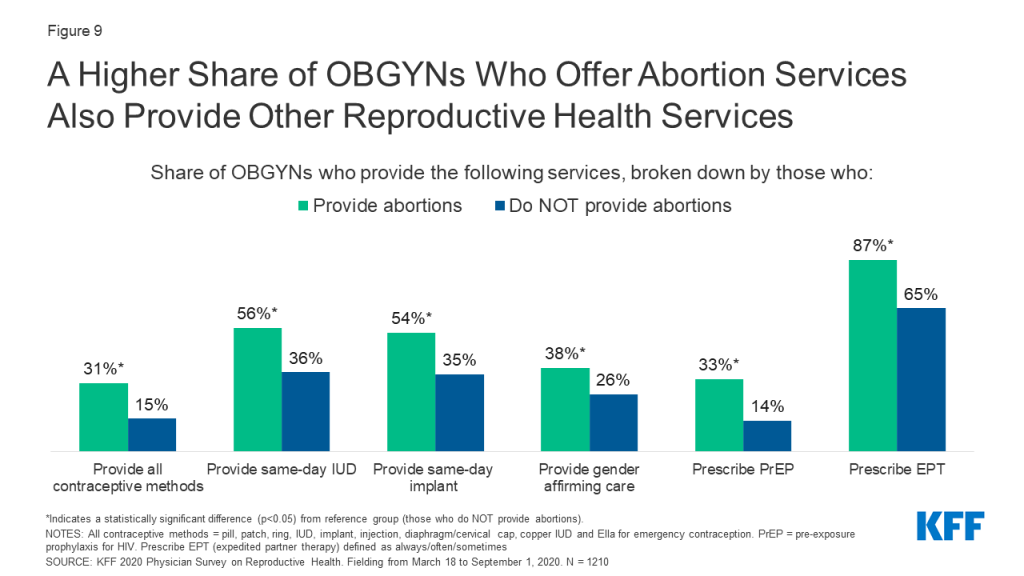

Compared to OBGYNs who do not provide abortions, a larger percentage of those who offered abortions provided a choice of all methods of contraception including emergency contraception, and provided same-day IUD and implant placement; this is notable given post-abortion contraception is an important component of abortion care for some women. A higher share of abortion providers also provided a wide range of STI services compared to non-abortion providers, including prescription of PrEP for HIV prevention and prescription of expedited partner therapy (EPT). It was also more common for abortion providers to provide gender affirming care compared to OBGYNs who did not provide abortions at their practice (Figure 9).

characteristics of OBGYNs who DO NOT provide Abortions

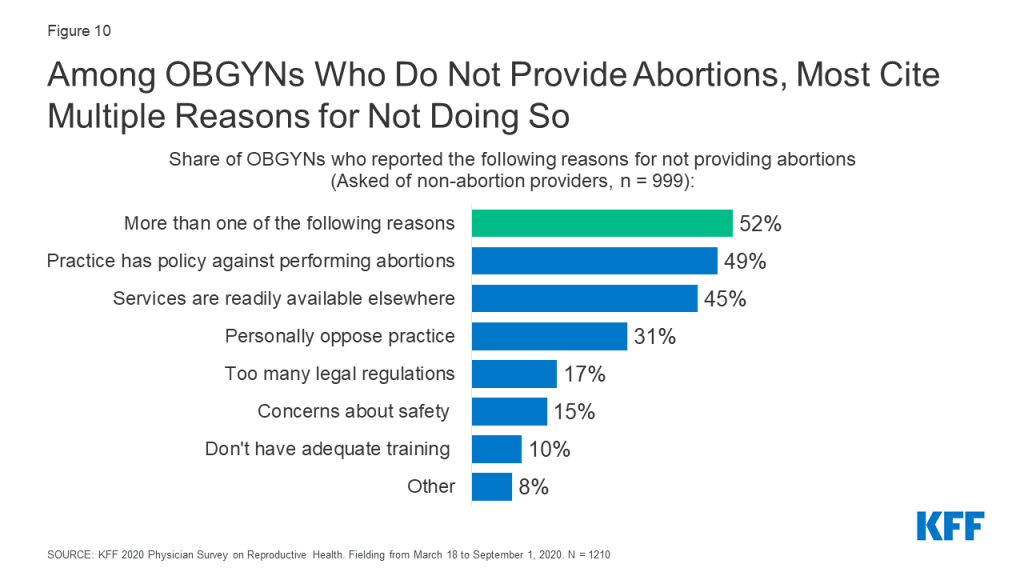

Among OBGYNs who do not provide abortions in their practices, most cited more than one reason for not providing abortions. About half (49%) say their practice has a policy against abortions, 45% say services are readily available elsewhere, 31% personally oppose the practice, 17% say there are too many legal regulations and 15% cite safety concerns for staff as their reasons for not providing abortions (Figure 10).

Only 10% reported they did not have adequate training to be providing this service, however this number was higher among the youngest group of physicians, age <45, compared to all older groups (age <45: 20%, 45-54: 7%, 55-64: 3%, 65+: 3%). This may reflect changes to abortion training over time. In 1996, the accrediting organization for OBGYN, the ACGME, instituted a training requirement for OBGYN residency programs to provide training in abortion provision, with opt out options for those with religious or moral objections. In a 2002 study of U.S. OBGYNs, it was found that younger OBGYNs were more likely than older OBGYNs to provide abortion, which was attributed to this change in medical training. However, a study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine pointed out that not all residency programs follow the ACGME requirement, and that abortion training may have become more limited in recent years due to institutional policies, state laws, and mergers with religiously-affiliated hospitals.

Among those who do not provide abortions, more male OBGYNs personally oppose the practice than female (39 vs. 27%). Additionally, among those who do not provide abortions, 61% of OBGYNs in health centers/clinics say their practice has a policy against performing abortions compared to 47% in private office-based practice; this could reflect federal and state level restrictions on the use of public funds for the provision of or referral for abortion found in the federal Title X program, the Hyde amendment and state laws.

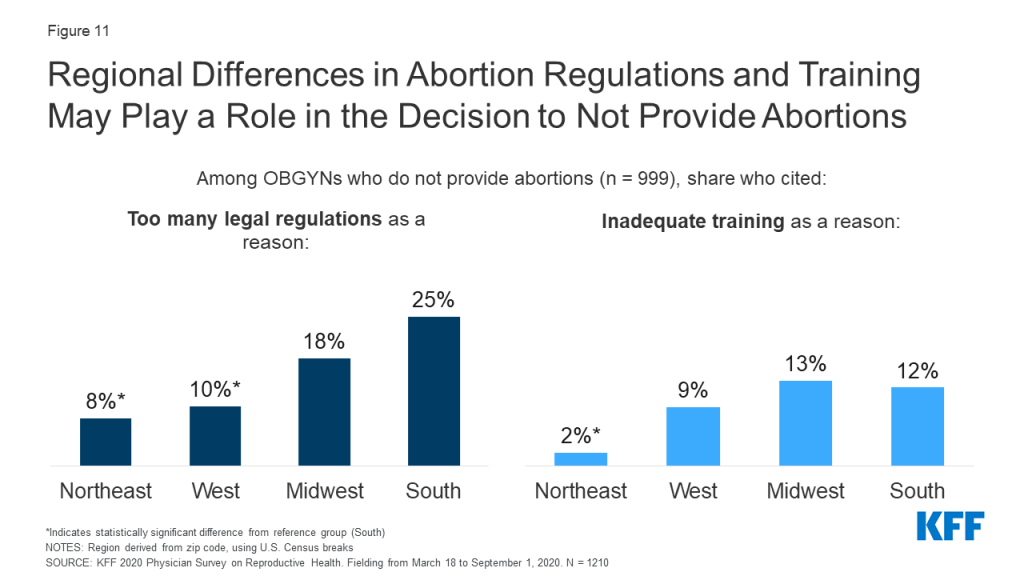

By region, a higher share of OBGYNs in the South reported that the high number of legal regulations associated with abortion (25%) was a reason they didn’t offer abortion compared to OBGYNs in the Northeast (8%) and West (10%). A higher share of OBGYNs in the Midwest (13%) and South (12%) also reported not having enough adequate training to provide abortion compared to OBGYNs in the Northeast (2%) (Figure 11).

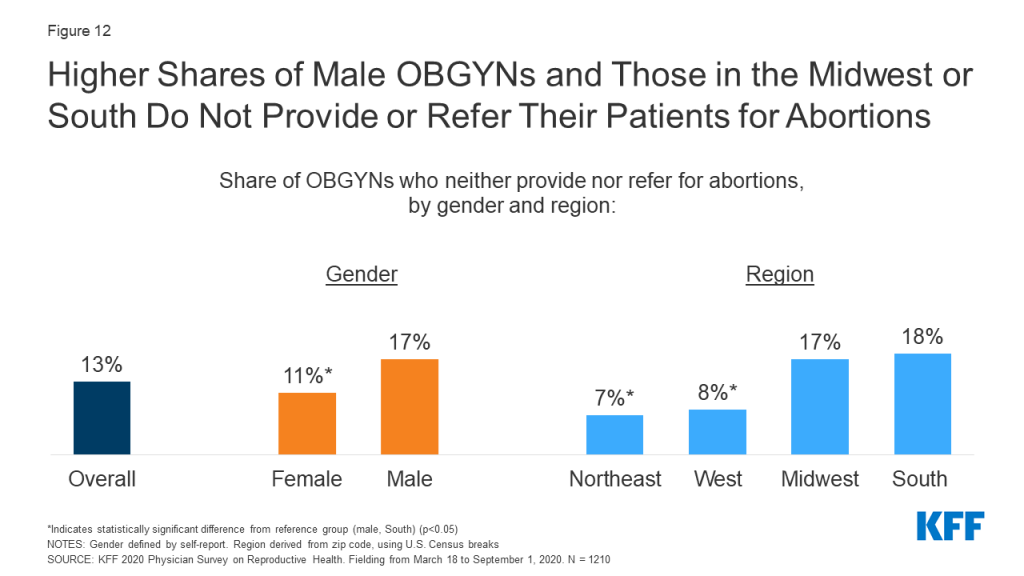

Most OBGYNs who did not provide abortions, however, referred patients for these services (Figure 5). A small share of OBGYNs (13%) neither provided abortions nor referrals for patients to obtain abortions at another practice or clinic. This was more common among OBGYNs who are male compared to female, and work in practices in the South and Midwest compared to the West and Northeast (Figure 12). No differences were identified by age, practice type, practice size or urbanicity.

Other Sexual and Reproductive Health Services

Care for Sexually Transmitted infections

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends testing for gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV and syphilis at differing points in people’s lives. The vast majority of OBGYNs provide onsite testing at their practice for gonorrhea and chlamydia (99%), syphilis (90%) and HIV (87%) (Table 7). About a third have onsite have lab processing as well for these STIs (38%/34%/34% respectively), rather than sending samples to outside labs.

| Table 7: Share of OBGYNs Who Provide Onsite STI Testing | ||

| Is onsite testing available at your practice for the following STIs? | ||

| Yes | No | |

| Gonorrhea and Chlamydia | 99% | <1% |

| Syphilis | 90% | 9% |

| HIV | 87% | 12% |

| SOURCE: KFF 2020 Physician Survey on Reproductive Health. Fielding from March 18 to September 1, 2020. N = 1210 | ||

While testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia was near universal, a small share of OBGYNs did not provide onsite testing for syphilis (9%) or HIV (12%) (typically collected via blood draws), meaning a patient would need to visit a separate facility for testing. This is important to note given the rising rates of congenital syphilis, primary and secondary syphilis among women, and HIV among certain groups of women in recent years. A higher share of OBGYNs in private office-based practices compared to health centers/clinics, and in small practices compared to medium and large did not test offer onsite testing for syphilis and HIV (Figure 13).

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Provision

According to the CDC, there remains a substantial gap, particularly among women, between the number of people with indications to be on the HIV prevention medication known as PrEP, and those who have been prescribed this medication. This may be in part due to a limited number of providers who prescribe PrEP. In our sample of OBGYNs, fewer than one in five (18%) prescribe PrEP for the prevention of HIV. This varied some by physician and practice characteristics; PrEP prescription was more common among younger OBGYNs ages compared to older, and among those in large practices compared to medium and small (Figure 14).

Expedited Partner Therapy

OBGYNs varied in how often they prescribed expedited partner therapy (EPT) for sex partners of patients being treated for gonorrhea or chlamydia. EPT describes the practice of prescribing STI treatment for a patient’s sex partner(s) without an in-person medical evaluation of their partner(s). About half of OBGYNs said they always (33%) or often (21%) prescribe EPT for gonorrhea and chlamydia, while some said they do so sometimes (15%). Nearly third said that they rarely (15%) or never (15%) prescribe EPT (Figure 15).

Additional SRH Services

Beyond contraception, STIs and abortion care, OBGYNs reported providing a range of other sexual and reproductive health services within their practices, while a small percentage refer their patients to other providers for these services (Table 8). Almost all OBGYNs reported they provide pap smears and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing (98%), colposcopies for abnormal pap smears (96%), basic infertility diagnostic services (90%) and prenatal care for low risk pregnancies (88%) within their practices, however some notable differences in service provision emerged. For example, fewer OBGYNs in health centers/clinics provided basic infertility diagnostics (e.g., lab testing, pelvic ultrasound, semen analysis) as compared to those in private office-based practices (78% vs. 92%). Additionally, provision of prenatal care was less common among older doctors (age 65+) compared to younger doctors, and those in small practices compared to medium or large (Table 9).

| Table 8: Health Care Services Provided by OBGYNs | ||

| Service | Provided within their practice | Referred to another provider |

| Pap Smears and HPV Testing | 98% | 1% |

| Colposcopies | 96% | 3% |

| Basic Infertility Diagnostic Services | 90% | 8% |

| Prenatal Care for Low Risk Pregnancies | 88% | 11% |

| Gender Affirming Care | 28% | 55% |

| NOTES: Responses do not total 100%, as they leave out those who answered that they neither provide nor refer for these services, and those who left the question unspecifiedSOURCE: KFF 2020 Physician Survey on Reproductive Health. Fielding from March 18 to September 1, 2020. N = 1210 | ||

| Table 9: Provision of Low-Risk Prenatal Care by OBGYNs | ||

| Provides prenatal care for low-risk pregnancies | ||

| Overall | 88% | |

| Age | <45 | 92* |

| 45-54 | 89* | |

| 55-64 | 89* | |

| 65+ | 75 | |

| Practice Size | Large | 95* |

| Medium | 93* | |

| Small | 74 | |

| *Statistically significant difference (p<0.05) from reference group in boldNOTES: Age defined by self-report. Practice size defined by number of full-time equivalent physicians and advance practice clinicians (small ≤3 FTE, medium 4-10, large >10).SOURCE: KFF 2020 Physician Survey on Reproductive Health. Fielding from March 18 to September 1, 2020. N = 1210 | ||

Notably the provision of gender affirming care was less commonly reported than other SRH services. About one in four (28%) OBGYNs reported that gender affirming services were provided at their practice (e.g. hormone therapy or gender affirming surgery) (Table 8). Another 55% refer patients for this care, while approximately one in ten OBGYNS (9%) neither provide nor refer for these services.

A higher share of OBGYNs in younger age groups compared to older worked at a practice offering gender affirming care, as did those who worked at large and medium practices compared to small. Regionally, provision of gender affirming care was more common among OBGYN practices in the West than in the Northeast, Midwest, and South (Figure 16).

Preparedness to Address SRH Needs of LGBTQ Patients

Providers varied in how prepared they felt to meet the sexual and reproductive health care needs of sexual and gender minority patients. Nearly nine in ten (88%) OBGYNs said they were very or somewhat prepared to meet the SRH needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual and queer patients, while the same was true for only 56% of OBGYNs when it came to transgender patients (Figure 17).

Perceived preparedness was higher among certain groups of OBGYNs. OBGYNs more often reported feeling very or somewhat prepared to meet the SRH needs of LGBTQ patients if they were female compared to male, and if they offered gender affirming care at their practices compared to not. Regionally, more OBGYNs in the West felt prepared to meet the SRH needs of transgender patients compared to those in the Midwest or South (Table 10).

| Table 10: Perceived preparedness to meet SRH needs of LGBTQ patients, by physician characteristics | |||

| Characteristics | Share of OBGYNs reported feeling very or somewhat prepared to meet the sexual and reproductive health needs of: | ||

| Gay, lesbian, bisexual and queer patients | Transgender patients | ||

| Overall | 88% | 56% | |

| Gender | Female | 90* | 61* |

| Male | 84 | 48 | |

| Region | Northeast | 87 | 56 |

| West | 89 | 66* | |

| Midwest | 87 | 54 | |

| South | 89 | 51 | |

| Practice provides gender affirming care | Yes | 93* | 81* |

| No | 87 | 47 | |

| *Indicates statistically significant difference from reference group in bold (p<0.05)NOTES: Gender and provision of gender affirming care defined by self-report. Region derived from zip code, using U.S. census breaks.SOURCE: KFF 2020 Physician Survey on Reproductive Health. Fielding from March 18 to September 1, 2020. N = 1210 | |||

Psychosocial Needs

In recent years, emphasis has been placed on incorporating screening for the social determinants of health and mental health needs into routine clinical care. We asked OBGYNs about their screening and intervention practices for four psychosocial needs—intimate partner violence (IPV), depression, housing and transportation. Nearly all OBGYNs screened patients for IPV and depression. A very small share of OBGYNs reported they do not screen any of their patients for IPV (4%) or depression (2%). This is perhaps not surprising given there are formal recommendations from USPSTF and ACOG to screen for both IPV and depression.

For social needs without formal screening recommendations however, screening was more variable. Almost half of OBGYNs said that they do not screen any of their patients for unmet housing needs (47%) or transportation barriers (45%) (Figure 18).

In the event a patient discloses or screens positive for one of these needs, most OBGYNs referred patients to outside resources for IPV (75%), depression (66%), housing (55%) and transportation (53%). Few had resources or a social worker onsite to address these needs (Figure 19). More than one in four OBGYNs (27%) said they neither have internal resources nor refer to external resources if a patient screens positive for unmet housing or transportation needs.

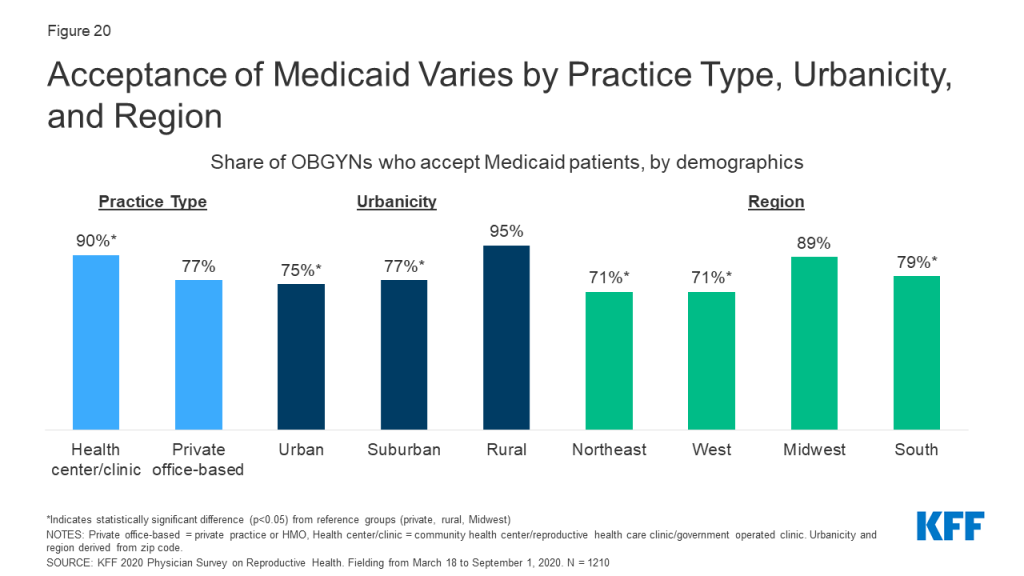

Report: Medicaid

Medicaid is a significant source of coverage for many people of reproductive age, covering 17% of non-elderly adult women in 2019 and financing in the U.S. and the majority of publicly-funded family planning services. Given the prominence of Medicaid as a payor for reproductive age women and services, it’s not surprising that many practices accept Medicaid. Nearly four out of five (78%) OBGYNs reported their practice accepts Medicaid, and 72% said that their practice is accepting new Medicaid patients. More OBGYNs in health centers/clinics accepted Medicaid patients compared to those in private office-based practices (90% vs. 77%). Additionally, a higher share of OBGYNs who practiced in rural areas compared to suburban or urban, and in the Midwest than the Northeast, South, and West accepted Medicaid (Figure 20). On average, OBGYNs who accept Medicaid estimated about half of their Medicaid patients (54%) were enrolled in managed care arrangements.

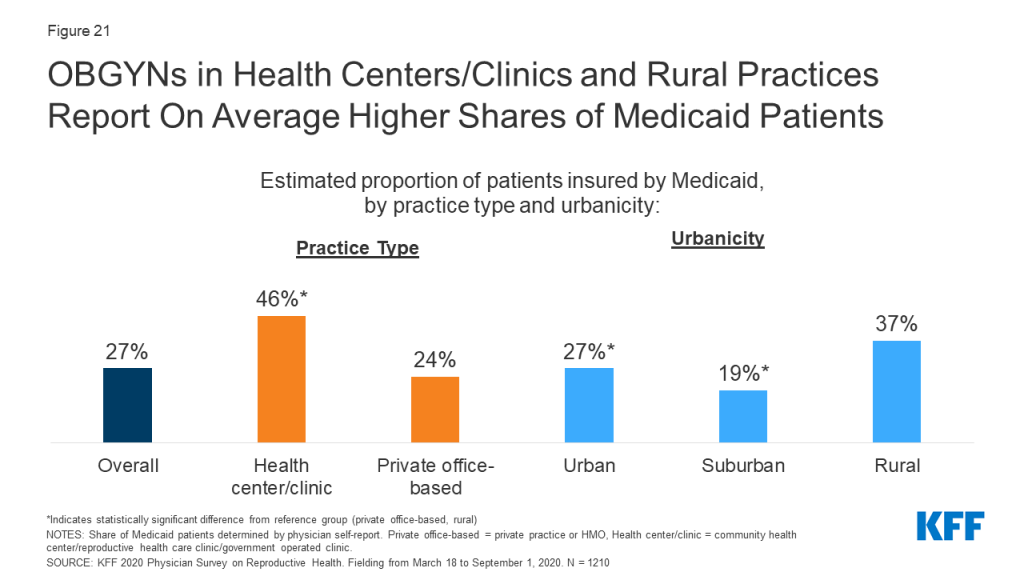

OBGYNs who practiced in health centers/clinics reported that, on average, 46% of their practices’ patients were on Medicaid, nearly double the rate of those who practice in private office-based settings (24%). On average, OBGYNs in health centers/clinics also saw a larger share of uninsured patients than private office-based practices (17% vs. 5%), as well as patients on other forms of public insurance like TRICARE and CHAMPUS (18% vs. 5%). OBGYNs in rural practices also reported, on average, higher shares of patients on Medicaid than those in urban and suburban practices (Figure 21).

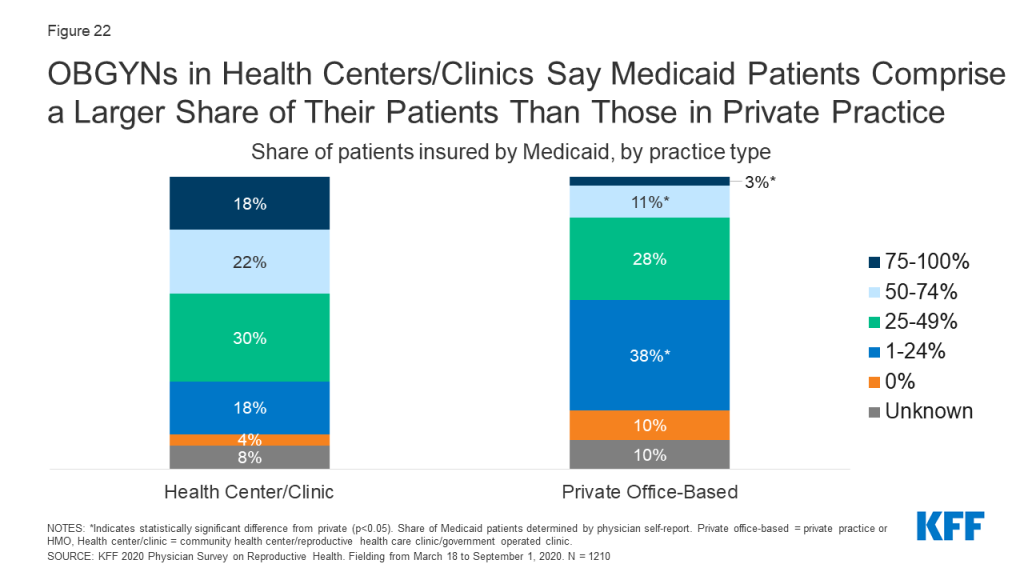

Some 40% of OBGYNs practicing in health centers/clinics reported that Medicaid patients accounted for over half of the patients seen in their practice, compared to 14% of those in private office-based practices (Figure 22).

Medicaid Coverage Limitations

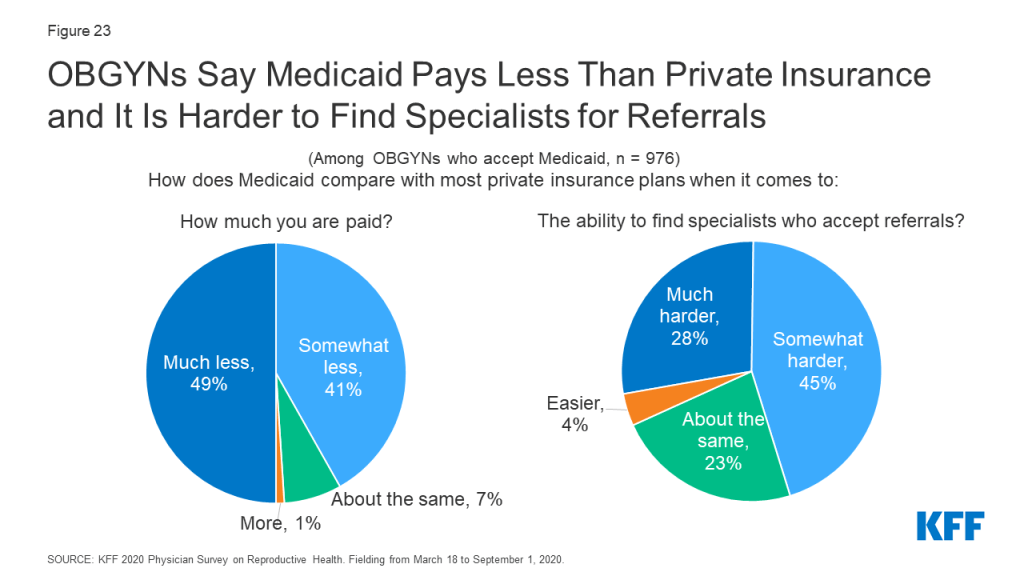

While most OBGYNs see patients with Medicaid, many reported payor challenges that came along with providing care for these patients. The vast majority of OBGYNs whose practice accepts Medicaid also reported that Medicaid pays much less (49%) or somewhat less (41%) than most private insurance plans (Figure 23). It was more common for OBGYNs in private office-based practice to say Medicaid pays less compared to those in health centers/clinics (91% vs. 82%), but providers in both settings reported lower payment rates compared to private plans.

Additionally, among OBGYNs who said their practice accepts Medicaid, nearly three in four said it was much harder (28%) or somewhat harder (45%) to find specialists who accept referrals for Medicaid compared with most private insurance plans (Figure 23). This challenge was reported by more than eight in ten OBGYNs in the South (83%), compared to lower shares in the Northeast (60%), West (72%), and Midwest (68%). OBGYNs in states that have not expanded Medicaid were also more commonly found to report this challenge compared to those in Medicaid Expansion states (84% vs. 68%), as were those in urban areas compared to rural areas (77% vs. 63%).

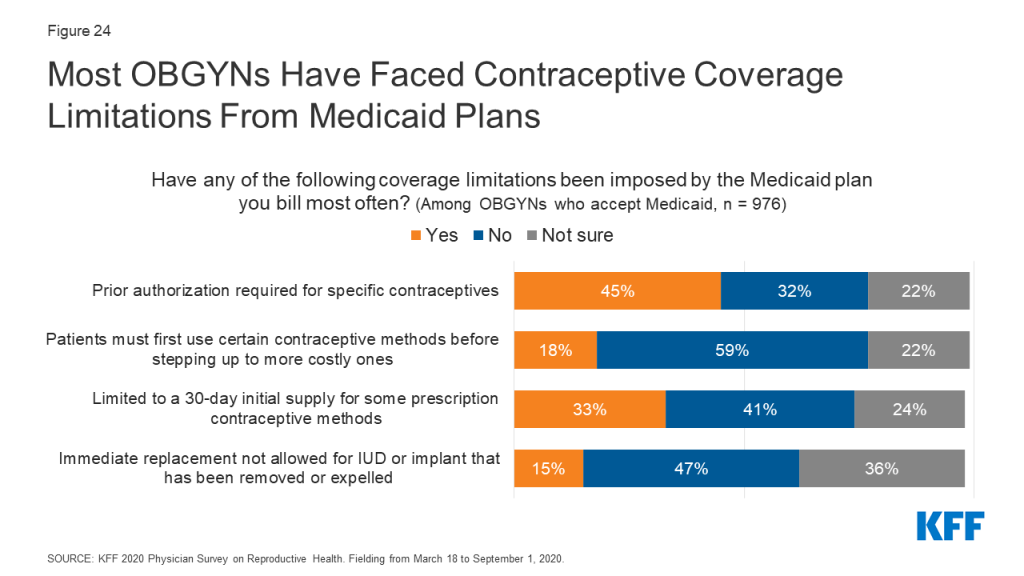

Most OBGYNs said they also faced Medicaid limitations specific to providing contraceptive care. Many had been required to obtain prior authorization for specific contraceptives (45%). About a third had been limited to prescribing a 30-day initial supply for some contraceptive methods (33%). Fewer had experienced their patients having to use certain contraceptive methods before stepping up to more costly ones, known as “step therapy” (18%), or replacement barriers for LARCs that had been removed or expelled (15%) (Figure 24). A sizable share of OBGYNs were not sure if these limitations had affected their practices or not.

The majority of OBGYNs who accept Medicaid (60%) said they had encountered at least one of the Medicaid limitations asked about with respect to Medicaid coverage of contraceptives; 28% reported one of the four limitations, 16% reported two limitations, 12% reported three limitations but very few reported all four limitations (4%).

Report: Policy Considerations

Cost of Care

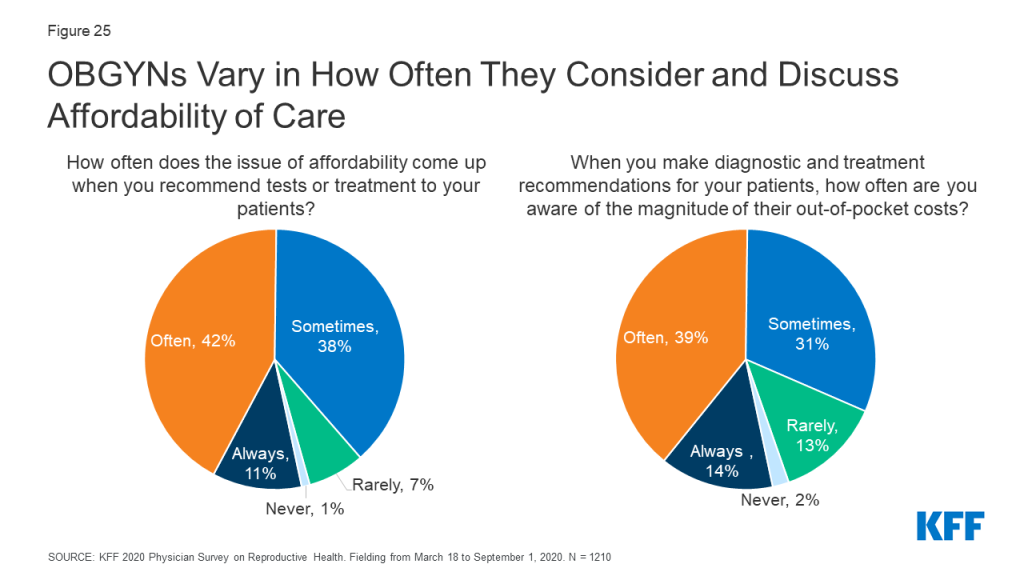

OBGYNs reported that affordability comes up commonly when talking to patients. Nine in ten OBGYNs said the issue of affordability always (11%), often (42%) or sometimes (38%) comes up when they recommend tests or treatment to their patients. Few said affordability came up rarely (7%) or never (1%).

Despite the topic of affordability arising frequently in patient-provider interactions, OBGYNs were not always aware of the out-of-pocket (OOP) costs patients were facing. When making diagnostic and treatment recommendations for patients, 14% said they were always aware of the magnitude of patients’ out of pocket costs. The rest said they were often (39%), sometimes (31%), rarely (13%) or never (2%) aware of these costs (Figure 25).

The issue of affordability and awareness of OOP costs varied by certain practice characteristics. OBGYNs in small practices compared to medium or large were more commonly found to report the issue of affordability always arising when recommending care to patients (small 18%, medium 9%, large 7%), and to report always be aware of the magnitude of OOP costs (small 23%, medium 11%, large 10%). There was no difference in how often the issue of affordability arises or awareness of OOP costs by practice type or share of Medicaid patients (25%+ vs. <25%).

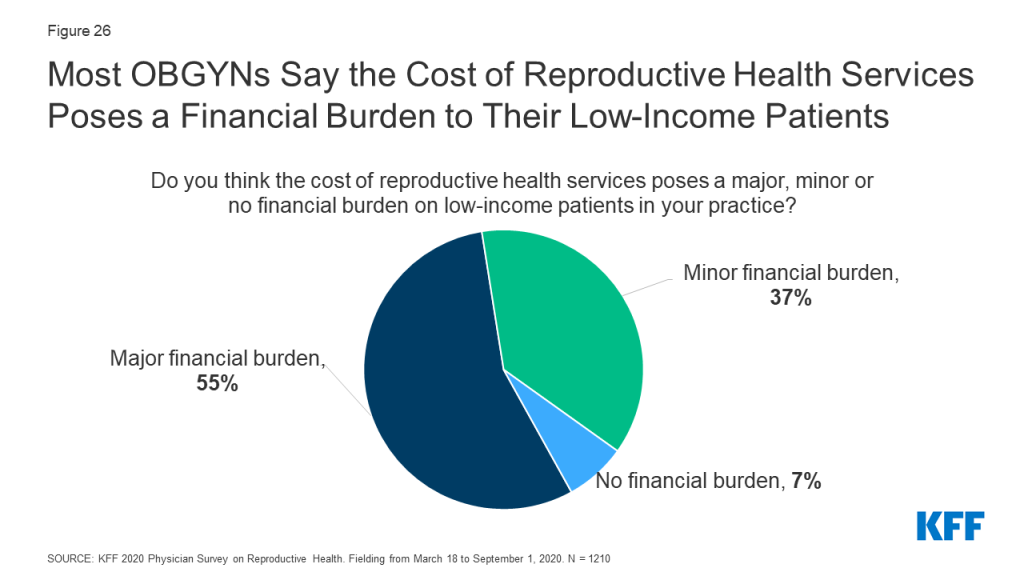

Nearly all OBGYNs acknowledged the cost burden that can be associated with seeking reproductive health care. Almost all OBGYNs said the cost of reproductive health services poses a major (55%) or minor (37%) financial burden for low-income patients in their practices, while only 7% believed it poses no financial burden (Figure 26). A higher share of OBGYNs in states without Medicaid expansion reported these services pose a major financial burden for low-income patients compared to OBGYNs in states with Medicaid expansion (63% vs. 52%).

Impact of the ACA on Contraceptive Use

The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) had several implications for women’s health care, and SRH care more broadly. Beginning in 2012, the law required nearly all private insurance plans to cover prescription contraceptive services and supplies without cost sharing to women. Since this regulation was implemented, over six in ten OBGYNs (63%) reported a significantly or somewhat increased share of their patients using any contraceptive method, while fewer reported no impact (34%) or a decreased share of patients using contraception (2%). In a similar vein, nearly seven in ten (69%) OBGYNs said the share of their patients who are able to select their desired contraceptive has increased significantly or somewhat since 2012 (Figure 27). Overall, these findings are consistent with other research documenting increases in contraceptive use, like IUD and implant use, since the contraceptive coverage requirement was implemented.

A higher share of OBGYNS in private office-based practices reported increased contraceptive use as compared to those working in health centers/clinics (any contraceptive use 66% vs. 47%, desired contraceptive 72% vs. 51% respectively). This could reflect the fact that those in private practice saw on average more patients with private insurance than those in health centers/clinics (60% vs. 28%); those in health centers/clinic on average saw a higher share of Medicaid patients who are already covered for contraceptive services, but many of their formerly uninsured patients could now be covered as result of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and have better access to contraceptive services and supplies.

Impact of Reproductive Health Policy Debates on Practice

Over the last year, several reproductive health policy debates have made their way into the news and judicial system. This includes changes to the Title X Family Planning program, debates over federal- and state-level abortion regulations and rulings on contraceptive coverage for religious employers. [For context, 27% of OBGYNs surveyed identified as Republicans, 40% as Democrats, 25% as Independents, and 6% as something else.]

Two thirds OBGYNs reported following developments or news regarding federal and state policy debates on reproductive health very closely (22%) or fairly closely (46%). The other third of OBGYNs reported they have followed these debates not too closely (27%) or not at all (4%) (Figure 28). It was more common for OBGYNs who provide abortions compared to non-abortion providers to report following reproductive health policy news very closely (36% vs. 18%), as it was for providers at practices that offer gender affirming services compared to those who do not (29% vs. 19%). This is perhaps not surprising given that access to abortion and care for transgender individuals have been the targets of a number of policy changes over the past year.

Several states across the country have passed an increasing number of laws regulating abortion in recent years, including gestational age limits and regulations on abortion providers and facilities. Most OBGYNs (68%) reported these new regulations did not impact their ability to provide quality reproductive health care to their patients, although about a quarter reported a negative impact (28%). Very few (3%) believed these regulations had a positive impact on their ability to provide quality reproductive health care (Figure 28). A higher share of the youngest group of OBGYNs perceived a negative impact of these regulations on provision of care compared to all other age groups (age <45: 40%, age 45-54: 23%, age 55-64: 19%, age 65+: 21%), as did OBGYNs in the Midwest (35%) and South (35%) compared to the Northeast (17%) and West (21%). Of note, abortion providers were just as likely to report a negative impact of these regulations as non-abortion providers (32% vs. 27%).

Career Satisfaction

It is well documented that many physicians suffer from burnout and career dissatisfaction. When asked if they could do things again based on their experience as a physician, 70% of OBGYNs reported they would choose the same specialty. A minority said they would choose a different specialty (19%), and few said they would not be a physician at all (10%) (Figure 29). There were no differences seen by physician age, race, practice type, urbanicity or practice size, however a higher share of men said they would choose a different specialty if they could do things again compared to women (24% vs. 16%). A higher share of abortion providers said they would choose the same specialty again compared to non-abortion providers (79% vs. 68%). A larger share of OBGYNs in the West said they would choose the same specialty compared to OBGYNs in the Northeast (76% vs. 63%) (Table 11).

| Table 11: Career Satisfaction of OBGYNs | ||||

| Characteristics | Based on your experience as a physician, if you had the chance to do things again would you: | |||

| Choose the same specialty | Choose a different specialty | Not be a physician at all | ||

| Overall | 70% | 19% | 10% | |

| Gender | Female | 72 | 16* | 11 |

| Male | 68 | 24 | 8 | |

| Age | <45 | 69 | 17 | 13 |

| 45-54 | 68 | 24 | 8 | |

| 55-64 | 73 | 18 | 8 | |

| 65+ | 70 | 20 | 9 | |

| Race and ethnicity | Asian | 68 | 20 | 11 |

| Black | 66 | 20 | 14 | |

| Other | 70 | 17 | 11 | |

| White | 71 | 19 | 10 | |

| Practice type | Health Center/Clinic | 66 | 24 | 9 |

| Private Office-Based | 70 | 19 | 10 | |

| Practice size | Large (>10 FTE) | 73 | 17 | 10 |

| Medium (4-10 FTE) | 72 | 19 | 8 | |

| Small (≤3 FTE) | 64 | 22 | 13 | |

| Urbanicity | Urban | 73 | 18 | 8 |

| Suburban | 64 | 24 | 12 | |

| Rural | 71 | 14 | 14 | |

| Region | South | 71 | 17 | 11 |

| West | 76* | 16 | 7 | |

| Midwest | 69 | 18 | 11 | |

| Northeast | 63 | 25 | 10 | |

| Practice provides abortions | Yes | 79* | 16 | 5* |

| No | 68 | 20 | 11 | |

| *Indicates statistically significant difference from reference group in bold (p<0.05)NOTES: Region derived from zip code, using U.S. census breaksSOURCE: KFF 2020 Physician Survey on Reproductive Health. Fielding from March 18 to September 1, 2020. N = 1210 | ||||