Medicaid Coverage of Family Planning Benefits: Findings from a 2021 State Survey

Key Findings

Introduction

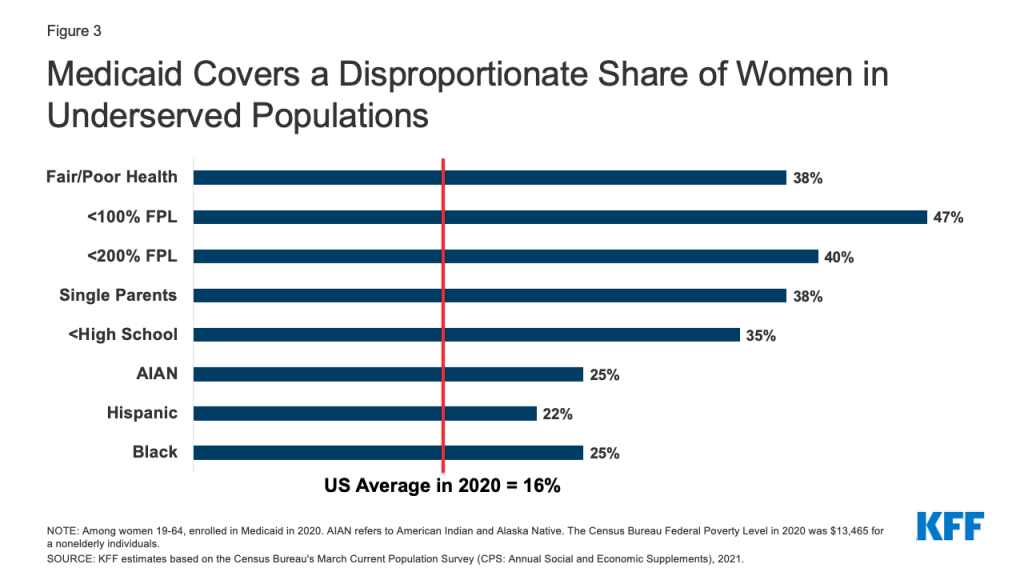

Medicaid is the primary funding source for family planning services for low-income people and is jointly financed and administered by the federal and state governments. The federal Medicaid statute establishes minimum federal standards, and for decades, has classified family planning as a mandatory benefit category that all state programs must cover, but does not define exactly what services must be included. For the most part, these services are defined by the states within broad federal guidelines. This report presents findings from a 2021 survey of states on policies related to coverage of family planning services under Medicaid.

The range of family planning services that states make available to their beneficiaries is shaped by many factors, including longstanding federal policies related to coverage of family planning services, federal requirements for coverage of preventive services and prescription drugs, and states’ application of utilization controls such as maintaining preferred drug lists (PDL), requiring the use of generics before brand names, step therapy protocols, and prior authorization. States have considerable discretion regarding Medicaid eligibility criteria, managed care enrollment, and payment structures which also affect beneficiaries’ coverage for and access to family planning care as well as the amount, duration and scope of the services that are covered.

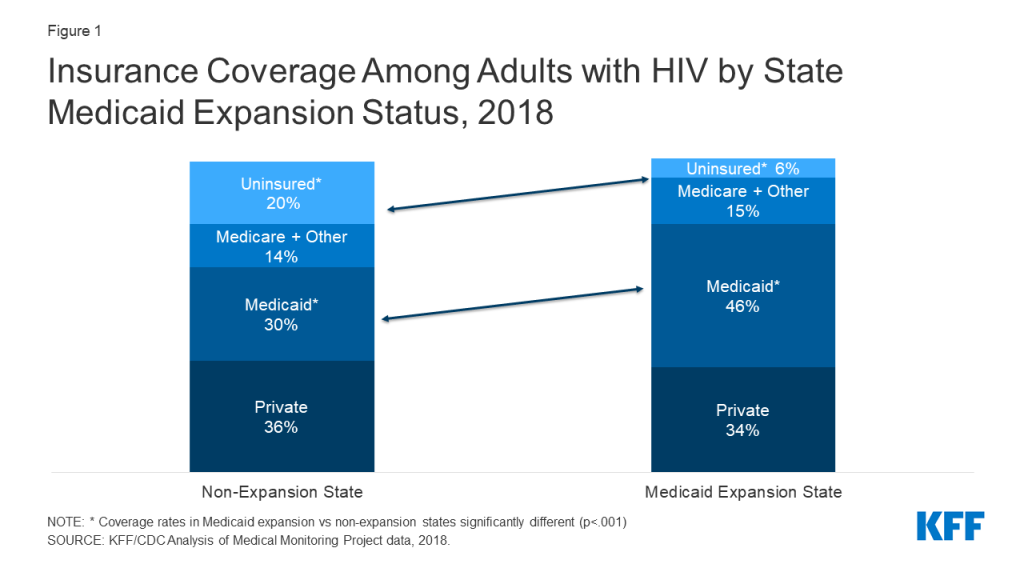

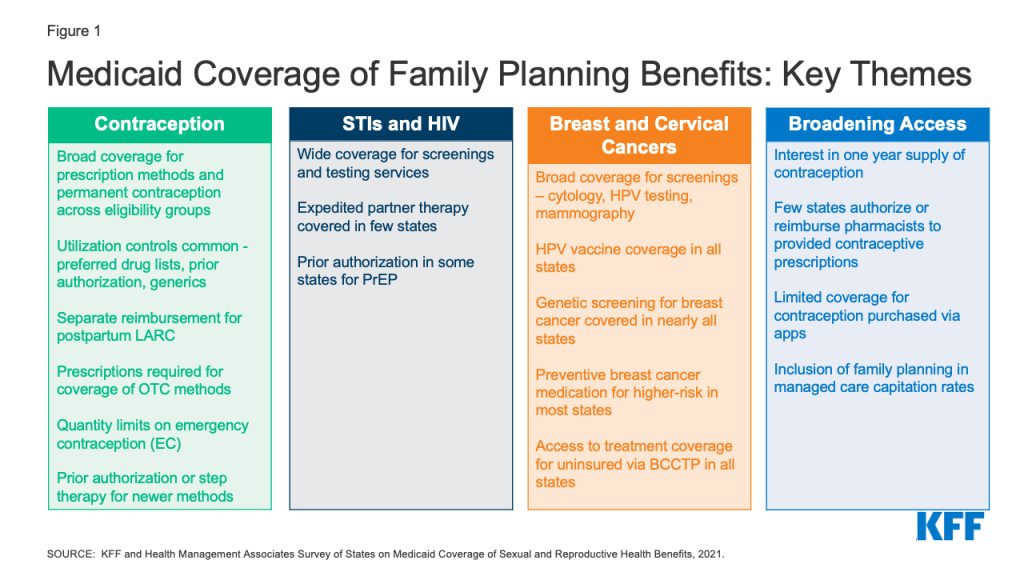

To obtain information about state Medicaid family planning coverage policies for adults, KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) conducted a survey of state Medicaid agencies regarding coverage of sexual and reproductive health care services. Federal standards for different Medicaid eligibility pathways may vary: traditional Medicaid eligibility, which was in place prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Medicaid expansion pathway in states that have expanded eligibility under the ACA, and limited scope family planning programs for individuals who do not qualify through other pathways. Where relevant, differences in state policies between these pathways are highlighted. This report presents survey findings from the states that responded (41 states and District of Columbia) about coverage policies for fee-for-service Medicaid in place as of July 1, 2021, for the following categories of family planning benefits: prescription contraceptives, over-the-counter methods, STI and HIV services, well woman care, breast and cervical cancer services, and managed care services. Figure 1 summarizes key themes from the survey findings.

Key Takeaways

Contraception

While all responding states (41 states and DC) cover prescription contraceptive methods approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), many apply utilization controls such as quantity limits, age restrictions, generic requirements, and Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs). Federal rules require state Medicaid programs to cover all prescription drugs from manufacturers that have entered into a federal rebate agreement. As a result, all state Medicaid programs have open formularies that include coverage for all prescription contraceptives. However, to control costs and promote quality, states may employ utilization controls that can restrict access to specific drugs. Common controls include limiting the medication quantity that can be prescribed at one time, requiring use and trial of generics before a brand name product, implementing a preferred drug list, and requiring prior authorization before a certain product can be reimbursed. Some states, for example, use utilization controls to limit access to newer contraceptive products like the Annovera Ring and Phexxi.

Few states reported imposing utilization controls on coverage of intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants. Most states also reported separate reimbursement for postpartum IUDs and implants rather than inclusion in a global payment for pregnancy-related services. IUDs and implants, the two forms of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), are among the most effective methods to prevent pregnancy and also the most expensive. In recent years, there have been considerable state and federal efforts to facilitate access to LARCs by improving reimbursement, particularly in the postpartum period, an important time for birth spacing and prevention of unwanted or mistimed pregnancies. Very few states reported imposing limitations on access to these methods, and most of the responding states reported reimbursing postpartum LARCs separately from a maternity global fee to clinicians and hospitals, averting what would otherwise result in a financial disincentive for postpartum LARC placement.

All responding states cover at least one form of emergency contraception (EC) pill under their traditional Medicaid program, but some states impose quantity limits and many require prescriptions for Plan B, even though it is approved for over-the-counter availability for EC pills. Emergency contraceptive pills prevent pregnancy if taken within the first few days after unprotected sex. They are not abortifacients as they cannot disrupt an established pregnancy. All but one state report coverage of prescription emergency contraceptive pills (ella or ulipristal acetate) across eligibility groups, and all but two cover over-the-counter (OTC) Plan B (levonorgestrel) under their traditional Medicaid programs. Far fewer states, however, reported covering Plan B without a prescription (7 states). Providing coverage without a prescription can expedite access, especially for a contraceptive with a short window of effectiveness such as emergency contraceptive pills.

Most states do not have a process for covering over-the-counter (OTC) methods such as condoms or sponges without a prescription. Thirty-eight states reported requiring a prescription from a provider to cover OTC methods, consistent with federal guidance that a prescription is required to obtain federal Medicaid matching funds. Ten states, however, reported covering some or all OTC contraceptives by expanding pharmacists’ scope of practice to prescribe and dispense specific contraceptives, either independently, under the supervision of a licensed provider with prescribing authority through a collaborative practice agreement (CPA), or through protocols such as a statewide “standing order.”

STIs and HIV

Nearly all reporting states cover testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and routine HIV screening under their traditional Medicaid program, and almost all states align non-contraceptive family planning benefits across eligibility pathways within their state. Care for STIs is typically considered part of clinical family planning services. Under Medicaid, however, STI treatment is classified as a “family planning related” service. All responding states reported covering STI testing, treatment, and counseling under their traditional Medicaid program, and almost all align coverage across eligibility groups. Additionally, almost all the responding states also reported covering routine HIV screening in their traditional Medicaid programs.

Few states, however, reported covering Expedited Partner Therapy (EPT) which is endorsed by the CDC as an effective method to control the transmission of STIs. Expedited partner therapy (EPT) enables the treatment of the sexual partners of a patient diagnosed with an STI without examination and is recommended by the CDC for treatment of STIs. However, just nine of the responding states reported EPT coverage.

Some states require prior authorization for the provision of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), a medication taken to prevent HIV acquisition, and some states do not cover it as a benefit under limited scope family planning programs. PrEP medications can prevent individuals from acquiring HIV, and are recommended for individuals at higher risk of HIV infection. Like other pharmaceuticals, Medicaid programs are required to cover PrEP, but 12 of the responding states reported having a prior authorization requirement. Seven states reported that they do not cover PrEP as part of their limited scope family planning programs, where coverage is optional because states can define the family planning and related services that they include for beneficiaries in these programs.

Cervical and Breast Cancers

All the responding states cover services to prevent, detect, and diagnose cervical and breast cancer, but there is variation in the types of services that are included and whether they are covered under limited scope family planning programs. Screening for cervical and breast cancers is considered appropriate for provision during a family planning visit. Every responding state reported coverage in their traditional Medicaid program for HPV vaccines, cervical cancer screenings using cervical cytology and HPV tests, and colposcopy and LEEP or cold knife conization, which are recommended services following an abnormal screening. However, coverage for these services is not universal in limited scope family planning-specific programs.

All of the responding states cover screening mammograms for people eligible through the traditional Medicaid pathway, and most cover genetic screening (BRCA) and counseling as well as medication to prevent or reduce risk of breast cancer for women at higher risk. As with cervical cancer screenings, every participating state covers mammograms under traditional Medicaid, but not all cover them for enrollees in the limited scope family planning programs.

In addition to routine mammography, screening for genetic mutations and preventive medications are recommended for some women at higher risk for breast cancer. While these preventive services are considered optional under traditional Medicaid, 40 states cover genetic screening and counseling for BRCA mutations and 36 cover preventive medication for high-risk women in their traditional Medicaid program.

Broadening Access

While nearly half of responding states cover a one-year supply of contraceptives at a time, few states allow pharmacists to prescribe and be reimbursed for contraceptive services provided to Medicaid beneficiaries. Extended supply and pharmacist prescribing of contraceptives are two avenues for enhancing access to family planning services. A number of states report that they allow Medicaid coverage for a one-year supply of certain hormonal methods, including 18 states that permit a one-year supply of oral contraceptives. However, fewer than a dozen of the responding states reimburse for pharmacist provision of contraceptives.

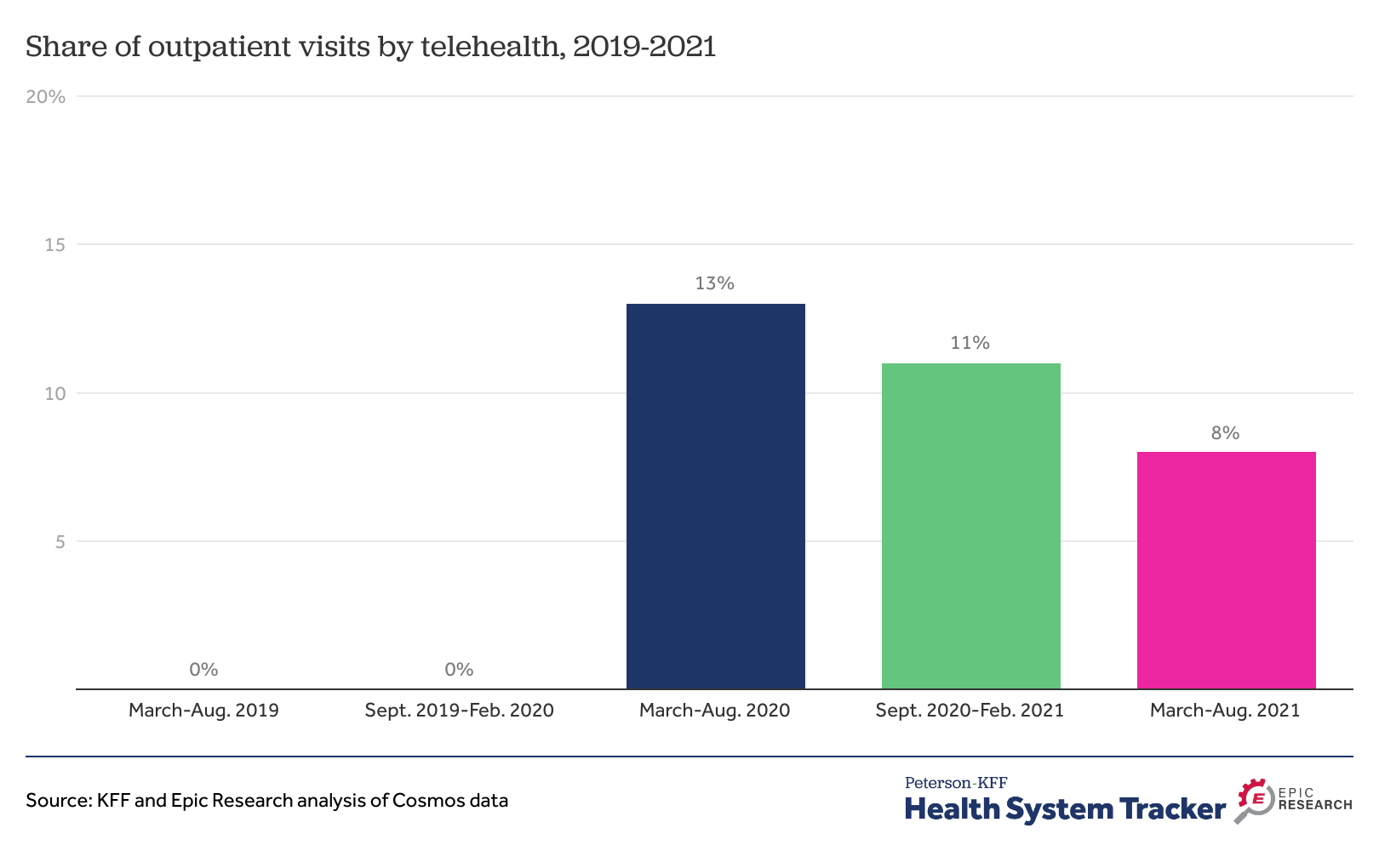

The availability of contraceptives via online apps is proliferating, but few states provide Medicaid coverage of contraceptives obtained through these platforms. In recent years, a number of companies have been providing mostly hormonal contraceptive methods through online platforms for customers to obtain contraceptives typically prescribed using an asynchronous telehealth protocol. While some of these companies do not accept any third-party payments, eight states reported that Medicaid covers contraceptive purchases secured through these apps. This is an evolving area, but overall Medicaid coverage for these products is limited at this time.

***

Medicaid represents a significant source of coverage of the full range of contraceptive methods and related family planning services for low-income people. In recent years, Medicaid enrollment, particularly of reproductive age adults, has grown as a result of state decisions to expand Medicaid under the ACA and to establish limited scope family planning programs. This survey finds robust coverage of many contraceptive services and supplies, but variation in the application of utilization controls. While there is broad coverage for prescription contraceptives (due to requirements and the drug rebate program) access to newer and OTC methods as well as adoption of policies that have been demonstrated to facilitate access, such as 12-month dispensing or allowing pharmacists to prescribe and be reimbursed, are less common. Furthermore, some states have not adopted protocols that facilitate the prevention of STIs and HIV such as expedited partner therapy or coverage for PrEP without prior authorization, important public health advances that have the potential to improve the sexual health of high-risk populations. In the coming years, particularly if access to abortion services becomes increasingly limited, the choices that states make regarding Medicaid eligibility and coverage for family planning services will make a critical difference in the reproductive health and well-being of millions of people across the nation.

Background

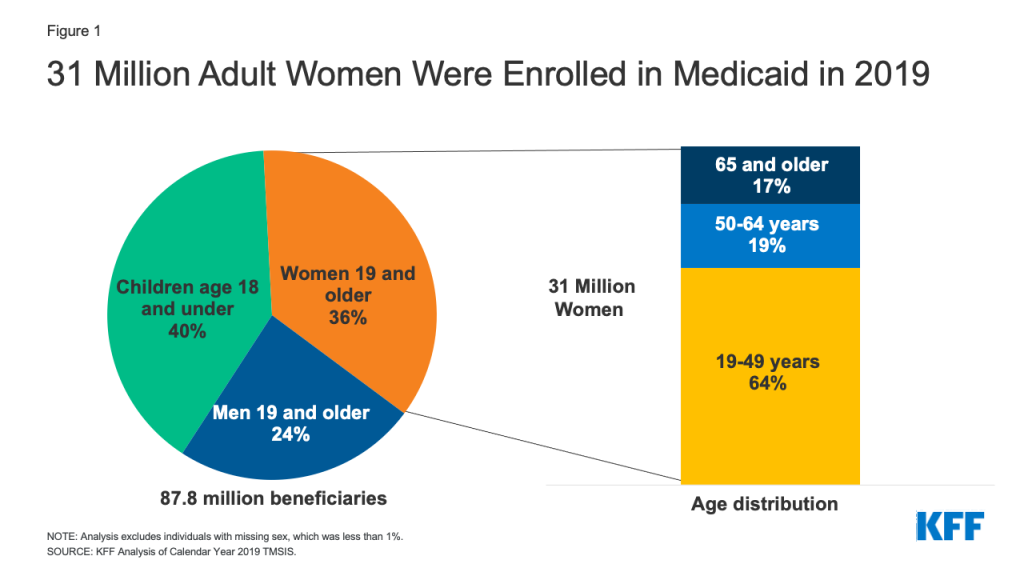

Medicaid, the nation’s health coverage program for low-income people, plays a primary role in financing and providing access to sexual and reproductive health services for millions of low-income individuals. The program covers more than 20 million adults ages 18 to 491 and is the largest source of public funding for family planning services. The program is operated jointly by the federal and state governments, who share responsibility for payment of services, while states set eligibility levels and determine the amount, duration, and scope of covered benefits within broad federal parameters.

Financing and coverage of family planning services is unique within the Medicaid program. Federal Medicaid law classifies family planning services and supplies as a “mandatory” benefit category that states must cover, but it does not formally define the specific services that must be included, giving states discretion as to which services they include in this category. In addition, federal law:

- Prohibits providers from charging copayments to beneficiaries or any other form of patient cost sharing for family planning services

- Establishes a 90% federal matching rate (FMAP) for the costs of services categorized as family planning, a higher proportion than for other services. States pay the remaining 10% of costs

- Entitles beneficiaries to obtain family planning services from any provider that participates in the Medicaid program, called free choice of provider, including for beneficiaries with mandatory enrollment in managed care organizations (MCOs)

Coverage for prescription drugs is another important element in Medicaid coverage of family planning services. All states have chosen to cover prescription drugs, even though it is an optional benefits category under federal law. Furthermore, all state Medicaid programs must maintain an “open formulary,” meaning that Medicaid covers nearly all FDA-approved drugs from manufacturers that agree to provide rebates for a portion of drug payments. States, however, can impose utilization control policies to limit spending and promote quality, which can restrict access to some drugs, including certain contraceptives.

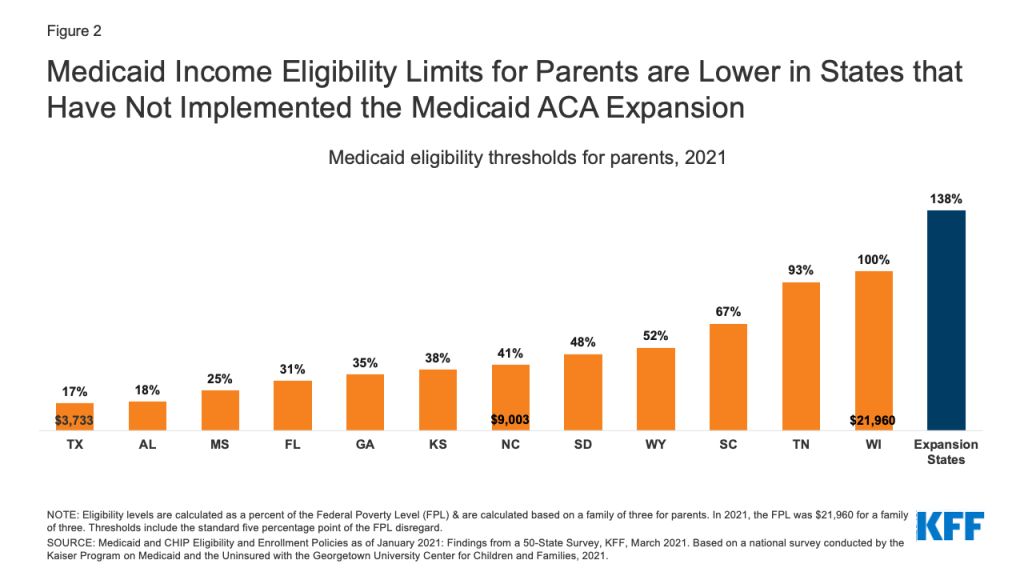

Enrollees who qualify for Medicaid through traditional pathways, those in place prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are entitled to coverage for family planning services. Several states have established special limited scope “family planning programs” that extend Medicaid coverage for family planning services only to individuals who are not eligible for traditional Medicaid (usually because their incomes exceed the state income eligibility thresholds or do not otherwise qualify for Medicaid). States can establish family planning-only programs either through federal Section 1115 research and demonstration waivers or State Plan Amendments (SPAs) that must be approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the federal agency that oversees the Medicaid program. States can decide which services they cover in these limited scope family planning programs, and pharmacy coverage under limited scope family planning programs is restricted to family planning and related services.

Additionally, states that have opted to expand Medicaid eligibility under the ACA are required to cover “essential health benefits,” including preventive services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), preventive services for women identified by the federal Health Services and Resources Administration (HRSA) based on the recommendations of the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI), and vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). The slate of preventive services recommended by these committees include several family planning and related services, specifically FDA-approved, authorized and cleared contraceptives with a prescription, screenings for STIs and HIV, screening for cervical and breast cancers, the HPV vaccine, well woman visits, and screening for intimate partner violence. These services must be covered under ACA Medicaid expansion, but that requirement does not apply to traditional Medicaid or limited scope family planning programs, which means that the benefits package could vary within a state for different Medicaid populations (Table 1). However, a 2015 KFF/HMA survey found that most states have aligned coverage of family planning benefits for all pathways, despite the differing requirements. States do vary, however, in the utilization controls that they choose to apply.

To understand the scope of coverage for sexual and reproductive health services, the utilization controls that states adopt, variations between and within states, and related state Medicaid policies across the nation, KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation) and Health Management Associates (HMA) conducted a national survey of states about policies in place as of July 1, 2021. States were asked primarily about coverage of services under traditional Medicaid and whether they align coverage policies in limited scope family planning programs and under their Medicaid expansions, where applicable.

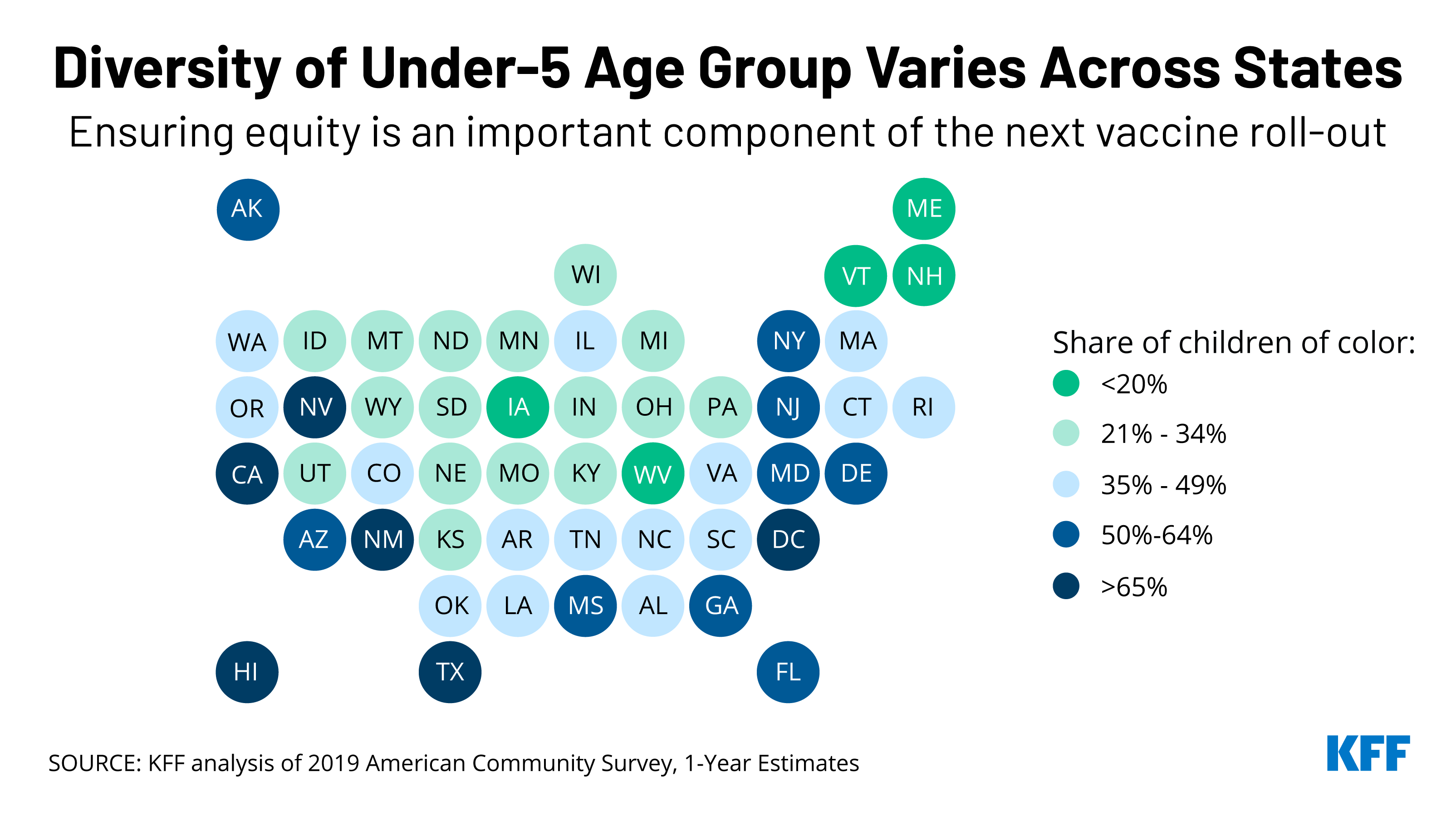

The survey was conducted between June 2021 and October 2021. Forty-one states and the District of Columbia responded to the survey (Figure 2). As of July 1, 2021, 31 of these participating states had implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion, and 11 had not implemented the expansion. Since July 1st, one of the 11 non-expansion states (Missouri) has implemented Medicaid expansion. Of the responding states, 24 states also offer limited scope family planning programs financed by Medicaid to individuals who do not qualify through other Medicaid pathways. Two additional states (Iowa and Missouri) operate limited scope family planning programs that are entirely state-funded because they exclude providers that offer both family planning and abortion services, disqualifying those programs from federal Medicaid payments. These state restrictions violate Medicaid’s freedom of choice requirement and Medicaid’s requirement to include all willing providers, which give Medicaid beneficiaries the right to seek services from any qualified provider that participates in a state’s Medicaid program. States that did not respond to the survey are: Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio, and South Dakota.

Presented below are detailed survey findings from 41 states and DC concerning coverage and utilization limits for reversible contraceptives and permanent contraception, well woman care, STI and HIV services, services for breast and cervical cancers, and requirements for managed care plans regarding coverage of family planning services. A majority of the states responding to the survey contract with managed care organizations (MCOs) under a capitated structure to deliver Medicaid services, including family planning. While the survey’s questions focused on state Medicaid policies and coverage under fee-for-service, these policies form the basis of coverage for MCOs.

Report

Detailed Findings

Prescription Contraception

The survey asked state officials about coverage policies for nearly all contraceptive devices and methods, including prescription and non-prescription methods, as well as reversible methods and permanent procedures for women and men. Reversible methods that are available over the counter (OTC) include condoms, spermicides, sponges, and one form of emergency contraception (i.e., Plan B). Reversible methods requiring a prescription include long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) – intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants; oral contraceptives; injectables, some emergency contraceptives; and various other products (including the contraceptive ring and the patch). States that have implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion must cover at least one product in each of the prescription contraceptive categories for adults in the expansion group, as required by the ACA’s preventive services coverage requirement.

Under federal law, and subject to exceptions for a few drugs or drug classes,2 state Medicaid programs are required to cover all drugs from manufacturers that have entered into a rebate agreement with the Secretary of Health and Human services under the federal Medicaid Drug Rebate program (known as “covered outpatient drugs”). As a result, all covered outpatient drugs are available in all state Medicaid programs under both managed care and FFS arrangements (although pharmacy coverage under limited scope family planning programs is restricted to family planning services and family planning related services3 ). To limit spending and promote quality, states are permitted to implement utilization controls, which vary between states and are often used to restrict access to more costly drugs. These utilization controls include preferred drug lists (PDL), requiring the use of generics before brand name drugs, step therapy protocols, and prior authorization. In the context of family planning, the covered outpatient drug requirements affect coverage of and access to contraceptives, treatments for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and preventive medications for conditions such as breast cancer and HIV.

All responding states cover most prescription contraceptive methods approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but many apply utilization controls such as quantity limits, age restrictions, generic requirements, and inclusion on a Preferred Drug List (PDL). Most states—with one exception—align their coverage of prescription contraceptives across all of their Medicaid eligibility pathways. Texas does not cover prescription Ella under its family planning waiver.

Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives (LARCs)

All 41 responding states and DC report covering the insertion and removal of intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants. None of these states reported requiring prior authorization for the devices. LARCs are highly effective at preventing pregnancy for extended periods of time, ranging from three to 10 years depending on the specific type that a woman uses. In the United States, three types of LARCs are available: hormonal IUDs, non-hormonal copper IUDs (also used as an emergency contraceptive), and implants. All states participating in the survey cover all LARC methods through all their Medicaid programs (Table 2).

States reported few utilization controls for LARC insertion and removal. Delaware manages hormonal IUDs on a PDL, and five states (Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Pennsylvania, and Vermont) impose quantity limits on LARCs based on a specified timeframe that is aligned with FDA guidelines. North Carolina does not cover LARC placement and removal under their family planning pathway outside of certain settings (e.g., office, local health department, Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), or Rural Health Center (RHC)). Pennsylvania covers one LARC removal every three years. California noted that most LARC devices are limited to clinic dispensing only, although the copper and Kyleena IUDs can be dispensed at a specialty pharmacy.

LARCs Provided Immediately Post-Labor and Delivery

States were asked how they structure reimbursement to clinicians and hospitals for LARCs inserted immediately after labor and delivery. Typically, prenatal care, labor and delivery, and postpartum care are reimbursed through a global maternity care fee, but many providers have reported that the global fee is not sufficient to cover the costs of inserting a LARC right after delivery or at the follow-up postpartum visit. The absence of a separate or increased fee to cover those LARC and insertion costs has been cited as a disincentive for some providers to offer birthing people the option of choosing a postpartum LARC. Recognizing this, CMS informed states in 2016 that they may separate the payment for LARC provision in the postpartum period from the global maternity fee.

Among the 42 states that responded to the survey, 26 reported that they provide separate reimbursement for LARCs placed immediately after labor and delivery from the traditional global maternity fee for both hospitals and clinicians. Thirty-four states provide separate reimbursement to the clinician for the LARC insertion procedure and LARC when placed immediately after labor and delivery while in the hospital or birthing center, while five states include the reimbursement to the clinician within the global fee structure. Thirty states reported providing a separate hospital reimbursement for a LARC device placed immediately after labor and delivery. Compared to the 2015 survey, more states report providing separate reimbursements to clinicians and hospitals for postpartum LARC insertion. DC reported that it does not provide a separate FFS reimbursement for immediate postpartum LARC, but that its managed care plans do, although the reimbursement methodologies vary across the four contracted health plans. Three states, Florida, Idaho and North Dakota, do not have a separate payment for LARC devices or insertions, but rather include reimbursement for both through global fees.

A few states reported other policy or reimbursement barriers to providing immediate postpartum LARC insertion. Nevada reported that hospitals will not allow providers to bring in LARC devices from outside the hospital, despite the state permitting reimbursement for these devices; New York cited the high cost of stocking LARCs as a barrier, and five states noted issues related to hospital claims and payment processes such as global fees or diagnosis-related group (DRG) pricing.

Oregon noted that, in practice, hospitals do not provide LARCs because the state’s claims processing system does not allow payment outside the hospital DRG—a bundled payment that includes the cost of treatments, medications and services a patient receives during the inpatient stay—and because the current DRG payment does not cover the hospital costs for LARCs. The state reported that it is currently considering options that would cover LARC costs for hospitals. North Carolina reported creating a new DRG that includes higher reimbursement for the LARC device and the insertion compared to the delivery-only DRGs.

Oral Contraceptives

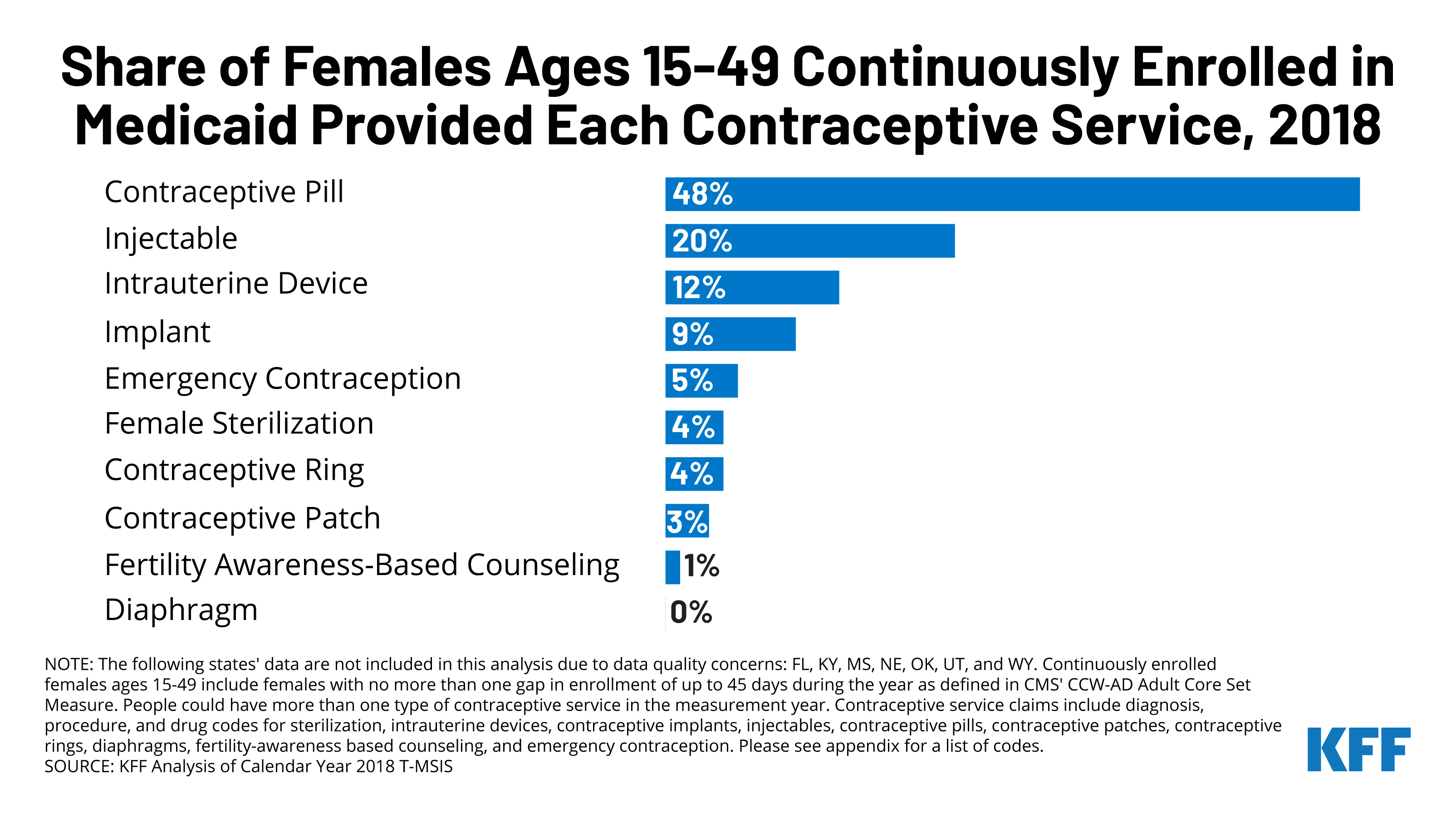

States reported supply limits, generic requirements, and inclusion on a Preferred Drug List (PDL) as the most commonly used utilizations controls. Oral contraceptives are the most commonly used form of reversible contraception among women in the United States. There are three formulations – combined, progestin only, and oral extended/continuous use, and many different products within these categories. Fifteen states use a PDL to manage the provision of oral contraceptives and 13 states either require or prefer the generic version of a drug. Eleven states reported that they restrict the quantity of oral contraceptives per prescription to a three-months supply (Table 3).

Five states apply limitations to Progestin Only Drospirenone (Slynd), a new progestin-only “mini-pill” that was first approved by the FDA in May 2019, and currently has no generic equivalent. Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Vermont require prior authorization before covering the drug. Maine and Tennessee require that a patient undergo step therapy, meaning they must first try using different oral contraceptives on their PDL before prescribing Drospirenone. Tennessee also requires step therapy before prescribing extended/continuous use oral contraceptives.

A growing number of states report they allow providers to dispense a 12-month supply of contraceptives. Eighteen of the responding states, compared to 11 states in 2015, indicated that they allow a 12-month supply of oral contraceptives to be dispensed at one time (Figure 4). Having an extended supply has been associated with better access and lower rates of unplanned pregnancy. Washington requires that hormonal contraceptives be dispensed as a one-time 12-month supply unless there is a clinical reason, or the client requests a smaller supply. Oregon reported that they currently allow a 100-day supply and that a system change is in development to allow for a 12-month supply. Three states—California, Missouri, and Washington—also allow coverage of a 12-month supply of the 28-day vaginal ring and the hormonal patch, and Washington covers a 12-month supply of the injectable contraceptive.

Postabortion Contraception

All responding states reported no additional restrictions to contraception provided immediately after an abortion during the same visit, regardless of whether the state covers abortions under Medicaid. The Hyde Amendment blocks states from using federal funds to pay for abortion services under Medicaid and other federal programs unless the pregnancy is a result of rape, incest, or the pregnant person’s life is in danger. However, states must cover family planning services and supplies for pregnant people regardless of whether they are seeking an abortion.

A couple of states noted that they apply the same or similar utilization controls to postabortion contraceptives that they apply to contraceptives obtained in other situations. Pennsylvania and Utah reported that limitations and utilizations controls differ based on the type of contraceptive a person chooses.

Hawaii, one of 16 states that uses state funds to pay for abortion services, reported that contraceptives provided after an abortion must be billed separately from the abortion. In Hawaii, abortion services are carved out and paid through their fee-for-service fiscal intermediary, while contraceptives are billed through the managed care plans.

Injectables, Diaphragm, Patch, Ring, and Phexxi

Almost all the responding states cover the remaining prescription contraceptives included in the survey across all available eligibility pathways. These methods are injectables, the diaphragm, contraceptive patch, vaginal ring (28 day and 1-year), and Phexxi, a vaginal contraceptive gel. All 41 responding states and DC report covering injectables, patches, and rings under traditional Medicaid. All responding states, except North Carolina cover diaphragms. A few states reported covering 12-month supplies of these prescription contraceptives. California, Missouri, and Washington cover a 12-month supply of the 28-day vaginal ring and the hormonal patch, and Washington reported they cover a year supply of the subcutaneous injectable.

The most common type of utilization control noted by states for these contraceptive methods are quantity or dosage limits. States that reported quantity and/or dosage limits for one or more of the methods include: Arkansas, Alabama, California, Florida, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, and West Virginia (Table 4). Some states impose age limits or restrict the type of provider that can provide or dispense the contraceptive. Alabama and Delaware require prior authorization for the diaphragm.

Some states use prior authorization or step therapy for coverage of two newer contraceptives, Annovera, a one-year vaginal ring approved by the FDA in 2019, and Phexxi, a non-hormonal vaginal gel approved in 2020. Once a new pharmaceutical has been approved and its manufacturer has entered into a rebate agreement under the federal Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, state Medicaid programs must cover that drug, but may subject it to utilization controls such as prior authorization or step therapy. All states reported covering Annovera, the one-year vaginal ring, and 39 reported covering Phexxi, which the FDA classifies as a spermicide under their traditional Medicaid programs. Three states reported that as of July 2021, they did not cover Phexxi.

Pennsylvania requires prior authorization before covering the one-year Annovera ring and Vermont requires that a patient first try at least three other contraceptives before they will cover it. Seven states—Arizona, Delaware, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Tennessee and Washington—require prior authorization for coverage of Phexxi. Vermont and Tennessee have step therapy requirements before covering Phexxi. Neither Annovera nor Phexxi has generic equivalents.

Emergency Contraceptive Pills

Emergency contraceptive (EC) pills, sometimes referred to as “the morning-after pill,” is a form of backup birth control that can be taken up to several days after unprotected intercourse or contraceptive failure and still prevent a pregnancy. It is not an abortifacient and cannot disrupt an established pregnancy. The three methods of EC that are available in the U.S. are copper IUDs (discussed earlier in this report), progestin-based pills, and ulipristal acetate. Progestin-based pills, commonly referred to as Plan B or levonorgestrel (generic) are available over-the-counter, without a prescription, while ulipristal acetate (also known as ella) requires a prescription and is effective for a longer period of time following unprotected intercourse than levonorgestrel.

All responding states cover at least one form of emergency contraception pill under their traditional Medicaid program. The survey asked states about their policies for ella (ulipristal acetate) and Plan B products (levonorgestrel). All states but one cover prescription ella under all eligibility pathways. Texas does not cover any form of emergency contraceptive pill under their limited scope family planning program. Mississippi and Rhode Island do not cover Plan B, which is the only form of EC that does not require a prescription, under any eligibility pathway.

Some states impose utilization controls on emergency contraception such as age and quantity limits. Two states, Florida and Oregon, impose a minimum age (12 and 17 respectively) on the provision of emergency contraceptives, even though the FDA does not have an age restriction on these drugs. Seven states have quantity limits, and five states require the use of the generic levonorgestrel. Maine utilizes a step therapy approach, requiring beneficiaries to try the over-the-counter method, Plan B, before using prescription ella. Alabama requires prior authorization for both OTC and prescription emergency contraception. These restrictions can delay receipt of EC, which must be taken within a few days after sex to be effective.

Non-Hormonal OTC Products (condoms, sponges, spermicide)

In addition to Plan B emergency contraceptive pills, states were asked about their Medicaid coverage policies for male condoms, spermicide and sponges, which are available over the counter. Federal law does not require states to cover most over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, with the exception of nonprescription prenatal vitamins, fluoride preparations for pregnant people, and certain nonprescription tobacco cessation products. If a state chooses to cover OTC drugs, a prescription is required to access federal Medicaid matching funds (although a state could choose to use state-only funds to cover OTC products without a prescription). The prescription requirement for OTC products can be a barrier because it can take time and additional resources to see a provider and obtain a prescription, but without coverage, these products may be unaffordable for many Medicaid beneficiaries. Many states reported covering OTC contraceptive products, but we found more coverage variability between states and between eligibility groups, compared to prescription methods, and most states reported requiring a prescription.

Over half of responding states (26 states) reported covering condoms, spermicide, and sponges in all eligibility pathways available within the state. Six states do not cover any of these three OTC products in their Medicaid programs: Alabama, Missouri, North Carolina, North Dakota, Tennessee and West Virginia. Thirty-two states cover male condoms, 31 cover spermicide, and 28 cover sponges under their traditional Medicaid programs. All three types of contraceptives were covered for ACA Medicaid expansion groups in 20 of the 32 states with that eligibility pathway. Indiana noted that OTC coverage varied in their expansion pathway because coverage policies differed across the managed care entities that provide coverage to that group. Most of the responding states with a family planning waiver or SPA cover male condoms, spermicide and sponges. Washington reported that in addition to covering OTC male condoms, spermicide, and sponges, they also cover natural family planning supplies, such as cycle beads.

With few exceptions, most states align coverage of OTC contraceptives across all available pathways in the state. Two states only cover OTC products through their limited scope family planning program —Mississippi only covers condoms, and Montana covers spermicide. Delaware reported they only cover the three OTC products for their expansion population. States also employ utilization controls to manage the coverage of OTC contraceptives. For example, California and New York both apply quantity limits to male condoms, spermicide, and sponges.

Most states require a prescription for Medicaid to cover any of these methods. While condoms, spermicides, sponges, and Plan B EC are non-prescription products, most states require prescriptions for Medicaid to cover them, and a prescription is required to obtain federal Medicaid matching funds. Ten states, however (DC, Illinois, Kansas, Maryland, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Utah, and Washington), reported covering some or all OTC contraceptives without a prescription. Just three of these states, Illinois, Maryland, and Washington, cover all four of these methods without a prescription. Pennsylvania covers male (and female) condoms without a prescription, and Washington reported Medicaid beneficiaries can obtain OTC contraceptives at a pharmacy with a Member ID card or at Health Care Authority (HCA) designated family planning clinic. Illinois Medicaid covers OTC products in limited quantities and in Oregon, pharmacists can prescribe Plan B. DC, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Utah and Washington reported covering OTC emergency contraceptive pills without requiring a prescription, although DC only covers OTC emergency contraception under its traditional Medicaid program and not through its limited scope Medicaid family planning program. Illinois noted that a standing prescription is kept on file and that women can access OTC emergency contraception at the pharmacy counter and have it covered by Medicaid. New York reported that beneficiaries can access Plan B at the pharmacy counter, and the pharmacist can then bill Medicaid in absence of a prescription. Delaware is in the process of implementing coverage of OTC emergency contraception for beneficiaries without a prescription.

Pharmacy Access

Some states allow pharmacists to furnish or dispense some contraceptives without a physician visit. Available now in a minority of states, pharmacy prescribing can provide another avenue of access for people who may not have a relationship with a health care provider, face barriers in getting to a provider visit, or who do not want to visit a provider for a contraceptive that they have been using for a long time. Some states will only reimburse pharmacist-prescribed oral contraceptives, while others also reimburse pharmacist-prescribing for other hormonal methods too, such as the ring and patch. State policies vary on other details, such as the mechanism for this prescribing authority (e.g., collaborative practice agreements or statewide protocols), age requirements, the duration of the supply, training requirements for pharmacists, whether the patient needs a prior prescription from a physician, and coverage under private insurance and Medicaid.

Eleven of the 42 responding states allow pharmacists to prescribe contraceptives for Medicaid beneficiaries. Eleven of the responding states (CA, CO, HI, ID, MD, OR, ND, TN, VT, WA, WV) allow pharmacists to prescribe some contraceptives under Medicaid as of July 1, 2021. Of these states: Colorado allows pharmacy prescribing for OTC products, providing better access to OTC products; Tennessee allows pharmacist prescribing for prescription contraceptives only; and the remaining states cover both pharmacist-prescribed prescription and OTC products. Eight of the states also reimburse pharmacists for a contraceptive visit (CA, CO, ID, MD, OR, TN, WA, WV), while three (HI, ND, VT) do not. Nevada reported that new state legislation had been enacted that would allow Medicaid to implement coverage of pharmacist prescribing in 2022.

Apps and Online Platforms

In recent years, a number of companies have created new products to dispense contraceptives outside of a clinical setting or a brick-and-mortar pharmacy and have applied technology to older contraceptive methods such as using an online app to track fertility using a calendar method. States were asked about their coverage of the natural family planning app, Natural Cycles, and coverage of contraception purchased through online platforms (also known as telecontraception) like Nurx and The Pill Club. Our survey found that few state Medicaid programs reported covering these products as of July 1, 2021.

Natural Cycles

Three states reported covering Natural Cycles, a fertility tracking app that can be used as a contraceptive. The app Natural Cycles received FDA clearance in 2018 to market as the first medical app that could be used as a method of contraception for women 18 and older. It tracks a woman’s menstrual cycle and identifies days on which they should use protection or abstain from sex. Users must take their temperature daily first thing in the morning using a basal thermometer and log it into the app. A similar app, Clue, has also received FDA clearance and will be available in the U.S. in 2022. Only DC, Illinois and Maryland report covering the app across their Medicaid eligibility pathways. However, it is not clear how Medicaid coverage of the app works, whether it is considered an OTC product or if clinicians are writing prescriptions for the app. Recent federal guidance have clarified that most private insurance plans and Medicaid expansion state programs must cover without cost sharing any FDA approved, cleared, or granted contraceptive products that have been determined to be medically appropriate by an individual’s medical provider, whether or not the product is listed in the FDA birth control guide.

Telecontraception

Few states reported covering contraception obtained through telecontraception platforms like Nurx and The Pill Club. In recent years, a growing number of companies have been providing contraception through online platforms for customers to access birth control, usually using an asynchronous telemedicine approach. Clients fill out a health questionnaire that is reviewed by a health professional, who prescribes contraception if the client meets the heath criteria and does not have any contraindications (such as migraines with aura or high blood pressure). Most companies offer a variety of oral contraceptive pills, the patch, the vaginal ring, and some offer emergency contraception. Contraception can either be delivered to a client’s home or be picked up at a local pharmacy.

In this survey, eight states said that they cover these services under traditional Medicaid. However, in separate work, KFF has identified at least 12 state Medicaid programs that cover telecontraception products. These discrepancies could be due in part to different interpretations of the question between states. Most of the states that reported coverage of telecontraception said it would be covered as long clients used a company that was enrolled as a Medicaid provider or pharmacy. Texas reported that as long as both the prescribers and the dispensing pharmacy providers were enrolled with the state Medicaid program, the claims would be covered. California noted while the contraception would be covered, any asynchronous visit initiated directly by the patient would not. Florida and Hawaii reported that while telecontraception apps are not covered through FFS, it is possible that managed care plans cover them. Prior KFF study found that most companies reported encountering barriers trying to work with state Medicaid programs.

Permanent Contraception Procedures

Sterilization procedures, or permanent contraception, are among the most effective methods of contraception. States that cover permanent contraception or sterilization procedures under Medicaid must meet certain conditions to prevent enrollee coercion. Protections against coercion include requiring the individual to be at least 21 years of age, to sign an informed consent form at least 30 days prior to a procedure as well as prohibition of federal matching funds for the sterilization of a mentally incompetent or institutionalized individual. These requirements are intended to protect against coercive practices that had historically forced sterilizations upon marginalized groups, including low-income women, women with disabilities, women of color, and incarcerated women.

All responding states cover sterilization procedures under their traditional Medicaid program and ACA Medicaid expansion pathway, and most align coverage for these services with their limited scope family planning programs. All states report that they cover tubal ligation when the fallopian tube is cauterized or clipped (postpartum and general), bilateral salpingectomy when the fallopian tube is removed, and vasectomy services. California, Texas, and North Carolina do not cover postpartum tubal ligation under their Family Planning SPA or Waiver pathways (likely because the family planning programs do not cover pregnant individuals), though they do cover tubal ligation outside of the postpartum period. Maine does not cover bilateral salpingectomy for their Family Planning SPA beneficiaries. Montana and Texas do not cover vasectomies under the family planning programs. Washington state reports that in addition to individuals 21 and older, the state covers sterilization services for beneficiaries who are 18-20 years old.

Well Woman Care

HRSA has adopted the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) recommendation that women receive at least one preventive visit per year. Well-woman visits provide an opportunity for women to meet with a clinician to discuss and address preventive health topics. Visits can include a broad range of services, such as assessment of physical and psychosocial function, primary and secondary screening tests, risk factor assessments, immunizations, counseling, education, preconception care, and many services necessary for prenatal and interconception care.

Preventive counseling is an important component of well woman care. In particular, the USPSTF and WPSI recommend clinician counseling for women on a number of topics, including contraception, intimate partner violence, STIs, and HIV, and the well-woman visit provides an opportunity to conduct that counseling. Private plans and Medicaid expansion programs must cover well woman visits and recommended preventive counseling without cost sharing. However, states can decide whether to cover and reimburse for well woman visits under traditional Medicaid.

Of the responding states, all but one cover well woman visits in their traditional Medicaid programs. Ten of these states have limits on the number of visits covered in a year: seven (AL, CO, MO, NC, PA, TX, WV) cover one well woman visit per year while Florida covers two office visits per month, and Louisiana covers two visits per year. Mississippi limits traditional Medicaid beneficiaries to 16 physician office visits per year and family planning program beneficiaries to four office visits per year. Alaska is the only state that reported not covering well woman visits. The state covers wellness checks through age 20 only.

All the responding states except DC cover preventive counseling on topics like contraception and intimate partner violence. Three states (Alabama, Mississippi, West Virginia) reported utilization controls that mirror those of their well woman visits. Thirty states reported that they cover preventive counseling as a component of an office visit, and seven states separately reimburse counseling. Arizona and Maine reimburse separately or as part of an office visit depending on how the visit is coded.

Cervical and Breast Cancer Services

The USPSTF recommends services to help prevent both cervical and breast cancers. Like contraception, Medicaid expansion states must cover these services for their expansion populations, but coverage is not required in traditional Medicaid or family planning programs. Most cases of cervical cancer are caused by infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), a common sexually transmitted infection (STI). Pap tests and HPV DNA testing are used to screen for cervical cancer, while colposcopy and LEEP or cold knife conization are follow-up services used after an abnormal screening result. The preventive services that USPSTF recommends for breast cancer include routine mammography, genetic screening for individuals with family history and certain risk factors, and preventive medications for some women at higher-risk for developing breast cancer.

Cervical Cancer

All the responding states cover a variety of cervical cancer screenings and tests, including cervical cytology also known as the Pap test, high-risk Human Papillomavirus (HPV) testing alone as well as co-testing for cervical cytology and high-risk HPV. All states cover these screenings under traditional Medicaid and align coverage across other eligibility pathways, except Wyoming and California. California has more restrictive coverage criteria for its family planning program, FamilyPACT. Under this program, the state covers screening services if they are provided along with a contraceptive visit. Some states reported covering cytology for individuals over 21 years old, in accordance with clinical recommendations. Colorado and North Carolina limit screening to one test per year. While the survey asked states only about fee-for-service policies, Tennessee, which only has managed care, noted that utilization management criteria vary between MCOs.4

All states cover the follow-up cervical screening services, colposcopy and LEEP or cold knife conization under traditional Medicaid, but some do not cover these services under their limited scope family planning programs. North Carolina, Virginia, Washington and Wyoming do not cover these follow up cervical cancer services under their family planning waivers. California’s family planning program follows the 2019 ASCCP5 Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines for Management of Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors for colposcopies and does not cover cold knife conization.

All, but one, of the responding states cover the HPV vaccine for adults in their traditional Medicaid program. Virginia reported that coverage for the HPV vaccine is limited to enrollees up to the age of 18 under traditional Medicaid. Four states (Alabama, California, North Carolina, and Washington) do not cover the HPV vaccine as a benefit in their family planning programs.

Breast Cancer

All the responding states cover screening mammograms in their traditional Medicaid programs. Of those, three states have age limits and other medical necessity criteria that must be met (CA, NC, WA).4 Six states do not cover mammograms in their family planning programs (CA, LA, MT, NC, WA, WY).

Nearly all (40 of 41) of the responding states cover genetic (BRCA) screening and counseling for high-risk women in their Traditional Medicaid program. The USPSTF recommends that women with a personal or family history of breast, ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal cancer receive counseling and screening for BRCA gene mutations. Fourteen states (AK, CO, CT, IA, MI, MT, NC, OK, SC, TX, UT, VA, WA, WY) require prior authorization for coverage. Nine states do not cover BRCA screening and counseling in their family planning waiver or SPA programs (CA, LA, ME, MT, NC, TX, VA, WA, WY). Alabama does not cover BRCA screening and counseling for any beneficiaries. One state (HI) did not answer this question.

Thirty-six states cover breast cancer preventive medication for high-risk women in their traditional Medicaid program, and five states do not (IA, IN, ME, VA, WY). The USPSTF recommends that clinicians offer risk-reducing medications to some women at higher risk for breast cancer. Of the states that do offer coverage, six limit the type of medication through their PDL, generic requirements, or prior authorization (CA, CT, MI, MT, OK, WA).

All the responding states reported participating in the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program (BCCTP). The BCCTP is an optional program for states to extend Medicaid coverage to uninsured persons who are diagnosed with breast or cervical cancer. While this program is a state option, all participate. Colorado, Florida, Kansas and Maryland administer the program through other state agencies. States can choose to extend Medicaid eligibility to persons screened or diagnosed with funding from the CDC’s National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) or, more broadly, persons screened under the NBCCEDP program, regardless of the funding source or diagnosis site. Of the states that responded to this question, 15 extend BCCTP eligibility only to persons screened or diagnosed through the CDC’s NBCCEDP, and 26 states extend Medicaid coverage under BCCTP eligibility to anyone screened and diagnosed through NBCCEDP regardless of the original funding source or diagnosis site.

Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs)

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are very common and encompass many different types of viral and bacterial infections. Rates of some STIs, including chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis have been on the rise in the United States. While STIs are often asymptomatic, they can have negative long-term health effects, such as pain, infertility, and miscarriage. Early treatment is important for curbing more serious illness as well as spread of infections to partners.

In the states that have implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion, STI counseling and screenings must be covered at no cost for beneficiaries enrolled in the expansion pathway. However, this requirement does not apply to those covered under traditional Medicaid or those enrolled in limited scope family planning programs where states have the option whether to cover specific STI screenings and treatments. Also, because CMS has classified STI treatment as a "family planning related service," federal funding for STI care is available at a state’s regular FMAP rates and not the enhanced 90% FMAP provided for family planning services. States may also impose nominal out-of-pocket charges for STI care under traditional Medicaid or in limited scope family planning programs.

All reporting states cover STI testing, treatment, and counseling under their traditional Medicaid program, and while most states align coverage across all eligibility pathways, there are some notable exceptions. Virginia and Wyoming reported that they do not cover STI treatment under their family planning waivers. North Carolina reported that beneficiaries are limited to one annual exam, six visits between exams, and a total of six courses of antibiotics annually. Oklahoma covers STI services, but generic medications are required, and services are subject to a possible copayment of $4.00. Texas commented that coverage for STI services is “subject to retrospective review of medical record and recoupment of payment if documentation does not support the service billed.”

Six states separately reimburse for STI counseling, and the remaining states reimburse it as a component of an office visit. Maine reported that physicians could be separately reimbursed for STI counseling, but other provider types such as FQHCs, RHCs, and family planning agencies are reimbursed as a component of the office/clinic visit. Separate reimbursement helps to compensate clinicians for the time they spend on counseling and may serve as an incentive to provide counseling to patients.

Only nine of the responding states reported coverage of expedited partner therapy (EPT) under any eligibility pathway. Expedited partner therapy (EPT) permits the treatment of partners of patients diagnosed with an STI without examination by providing the patient directly with extra doses for each eligible partner or by writing a prescription for the partner as well. The CDC has recommended this practice since 2006 in certain circumstances due to its success in reducing gonorrhea reinfection rates. Most states allow the practice, but many do not allow the patient’s insurance coverage to be billed for the partner’s treatment, which can create a financial barrier to care for the partner.

Of the nine states reporting EPT coverage, some limit coverage to certain diagnoses. For example, Indiana and Vermont limit EPT to gonorrhea or chlamydia diagnoses, and Tennessee covers EPT only for chlamydia. Massachusetts and Indiana will only cover treatment for the partner if they are also a Medicaid beneficiary. California will reimburse for the treatment of the Medicaid beneficiary and up to five partners. Michigan provides EPT outside of the Medicaid program through their Department of Health and Human Services HIV/STI program to all regardless of insurance status.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

The Medicaid program plays a major role in care of individuals living with HIV and is the largest source of insurance coverage for people with HIV. The number of Medicaid beneficiaries with HIV has grown over time as the program has expanded, people with HIV are living longer, and new infections continue to occur. The program covers a wide range of benefits, including screening, prevention, prescription drugs, and treatment services. The survey asked about state coverage of HIV screening and preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which are medications that can prevent infection. The USPSTF recommends routine screening for adults and adolescents ages 15 to 65 as well as PrEP medications for individuals at higher risk for HIV, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends routine HIV screening in health-care settings for all adults, aged 13-64, and repeat screening for those at higher risk.

Nearly all reporting states cover routine HIV screening in their traditional Medicaid programs. All but one of state surveyed cover HIV screening for all individuals under traditional Medicaid. The exception, Florida, covers HIV screening only for at-risk individuals in their traditional Medicaid program. States are required, at minimum, to cover “medically necessary” testing under their traditional eligibility pathway.

A dozen states report prior authorization requirements for PrEP medications. PrEP medications, which were first approved by the FDA in 2014, prevent individuals from acquiring HIV. There are two medications that have been approved for PrEP, under the brand names Truvada and Descovy. Truvada is approved for use as PrEP in males and females. Descovy is not approved for use as PrEP in females who are at risk for HIV through vaginal sex. Generics are available for Truvada but not for Descovy. While Medicaid programs are required to cover PrEP under the traditional eligibility pathway, they may apply utilization controls. Twelve of the responding states said they require prior authorization for PrEP and Washington requires prior authorization for brand name HIV PrEP medications only. Missouri reported that it requires prior authorization for PrEP in its traditional Medicaid program but not in its state-funded family planning program.

Although most states align their HIV testing and PrEP coverage policies, several states do not provide coverage for these services under their family planning waivers or SPAs. Washington does not cover HIV testing for beneficiaries in their family planning waiver. Washington, Virginia, Texas, New York, North Carolina, California, and Montana do not cover HIV PrEP under their family planning program, though North Carolina does refer members to participating drug stores and clinics. New York reports they are actively working to include coverage for PrEP for family planning SPA beneficiaries, and Texas requires providers to refer family planning waiver beneficiaries for treatment as necessary.

Managed Care

This survey asked states about fee-for-service coverage policies, but most of the survey states enroll the majority of adult beneficiaries in capitated managed care organizations (MCOs). While state Medicaid programs make determinations about the services that they will cover, for beneficiaries enrolled in managed care, coverage policies are established through the contracts that states sign with MCOs, which may vary between plans. Nine of the responding states (AL, AK, CT, ID, ME, MT, OK, VT, WY) do not have Medicaid MCO enrollment.

When a state chooses to cover family planning services under a capitated MCO, the state must implement policies, procedures, and contractual requirements that will allow the state to claim the enhanced 90% FMAP allowed for family planning services delivered under that capitated arrangement. The state must also ensure that the full costs of family planning services are covered and that MCO-enrolled beneficiaries are able to see any Medicaid provider of their choice, even if the provider is not in the MCO’s network. State policies regarding benefits and payment rates under fee-for-service may set minimum standards for MCOs, but MCOs may elect to cover benefits beyond what is required in their contract and may pay providers more than the minimum fee-for-service rate. We asked states if they include family planning services within MCO capitation rates and whether they claim the enhanced 90% FMAP for family planning services purchased by MCOs. We also asked if their MCO contracts explicitly address utilization controls for family planning services.

Most of the responding states have capitated MCO contracts that include family planning services in the capitation rate. Most, but not all responding states with MCOs (26 of 31) reported that they claimed the enhanced 90 percent federal matching rate for family planning services provided through MCO. Four states (LA, MT, ND, WV) reported that they do not claim the enhanced 90% FMAP, and one state (Kansas) did not answer this question. Thirteen states reported that they explicitly address potential utilization controls on family planning services in the MCO contracts. Five states prohibit the use of prior authorization for family planning services and supplies in their MCO contracts. One state, Washington, stated that they are explicit in MCO contracts that plans must cover a one-year supply of contraceptives and all OTC methods without a prescription, as required by laws in that state.

Three states (OR, IL, TX) report that they contract with MCOs that have a “conscience” or religious exemption from the requirement to provide family planning services. Insurance plans that are “faith-based” may not cover the full range of family planning services over objections allegedly based on religion, limiting access for beneficiaries particularly if the plan has a narrow provider network. All three of these states indicated that beneficiaries can receive coverage for family planning services outside of the plan network if their plan has any religious objections. Illinois reported that plans must have contracted facilities nearby that can provide family planning services.

Conclusion

Family planning services have been part of the Medicaid program for decades. Over time, the field has evolved, with changes in clinical practices and an expansion in the realm of services that address sexual health beyond pregnancy prevention. On the whole, this survey finds that while all states cover a broad range of contraceptive methods, some impose limitations like prior authorization or quantity limits that are sometimes used to help states control spending but can affect beneficiaries’ ability to obtain their preferred contraceptives in a timely manner. Access to newer products, over-the-counter methods, and online services are often less available to those enrolled in Medicaid. We also found less uniformity in coverage policies for recommended non-contraceptive services like expedited partner therapy, to curb the spread of STIs, and PrEP, to prevent HIV infection in higher risk populations.

The survey also illustrates the regulatory complexities that impact coverage for specific services within a state. One of the features of the Medicaid program is flexibility for states to establish coverage policies on their own, within broad federal guidelines. The sheer breadth of family planning products, the different eligibility pathways, the range of utilization controls, varying levels of reimbursement between family planning and related products, and intersection with other public health programs in a state mean that it can be very difficult to ascertain coverage for the range of benefits for the different eligibility pathways available under Medicaid. This survey asked about state policies under fee-for-service, which also form the basis for coverage policies in managed care organizations. For beneficiaries trying to understand and use their Medicaid coverage for important preventive services, particularly if they rely on specific products, it can be formidable to navigate and assess exactly what is and is not covered.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the numerous staff members in state Medicaid agencies who participated in the survey. The authors also thank the following individuals, who provided input in the survey questionnaire, data management, and analysis: Jim McEvoy and Kraig Gazley of Health Management Associates; Michael Policar of UCSF; Cathy Peters of the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network.

Appendices

Endnotes

- KFF estimates based on the Census Bureau’s March Current Population Survey (CPS: Annual Social and Economic Supplements), 2021. ↩︎

- Section 1927(d)(2) provides that the following drugs or classes of drugs, or their medical uses, may be excluded from coverage or otherwise restricted: (A) Agents when used for anorexia, weight loss, or weight gain. (B) Agents when used to promote fertility. (C) Agents when used for cosmetic purposes or hair growth. (D) Agents when used for the symptomatic relief of cough and colds. (E) Agents when used to promote smoking cessation. (F) Prescription vitamins and mineral products, except prenatal vitamins and fluoride preparations. (G) Nonprescription drugs, except, in the case of pregnant women when recommended in accordance with the Guideline referred to in section 1905(bb)(2)(A), agents approved by the Food and Drug Administration under the over-the-counter monograph process for purposes of promoting, and when used to promote, tobacco cessation. (H) Covered outpatient drugs which the manufacturer seeks to require as a condition of sale that associated tests or monitoring services be purchased exclusively from the manufacturer or its designee. (I) Barbiturates. (J) Benzodiazepines. (K) Agents when used for the treatment of sexual or erectile dysfunction, unless such agents are used to treat a condition, other than sexual or erectile dysfunction, for which the agents have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. ↩︎

- “Family planning related services are medical, diagnostic, and treatment services provided pursuant to a family planning visit that address an individual’s medical condition and may be provided for a variety of reasons including, but not limited to: treatment of medical conditions routinely diagnosed during a family planning visit, such as treatment for urinary tract infections or sexually transmitted infection; preventive services routinely provided during a family planning visit, such as the HPV vaccine; or treatment of a major medical complication resulting from a family planning visit.” CMS, SHO# 16-008, Medicaid Family Planning Services and Supplies, June 14, 2016; accessed at https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/sho16008.pdf. ↩︎

- [1] “Family planning related services are medical, diagnostic, and treatment services provided pursuant to a family planning visit that address an individual’s medical condition and may be provided for a variety of reasons including, but not limited to: treatment of medical conditions routinely diagnosed during a family planning visit, such as treatment for urinary tract infections or sexually transmitted infection; preventive services routinely provided during a family planning visit, such as the HPV vaccine; or treatment of a major medical complication resulting from a family planning visit.” CMS, SHO# 16-008, Medicaid Family Planning Services and Supplies, June 14, 2016; accessed at https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/sho16008.pdf. ↩︎

- American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. ↩︎