A New Use for Wegovy Opens the Door to Medicare Coverage for Millions of People with Obesity

The FDA recently approved a new use for Wegovy (semaglutide), the blockbuster anti-obesity drug, to reduce the risk of heart attacks and stroke in people with cardiovascular disease who are overweight or obese. Wegovy belongs to a class of medications called GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) agonists that were initially approved to treat type 2 diabetes but are also highly effective anti-obesity drugs. The new FDA-approved indication for Wegovy paves the way for Medicare coverage of this drug and broader coverage by other insurers. Medicare is currently prohibited by law from covering Wegovy and other medications when used specifically for obesity. However, semaglutide is covered by Medicare as a treatment for diabetes, branded as Ozempic.

What does the FDA’s decision mean for Medicare coverage of Wegovy?

The FDA’s decision opens the door to Medicare coverage of Wegovy, which was first approved by the FDA as an anti-obesity medication. Soon after the FDA’s approval of the new use for Wegovy, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a memo indicating that Medicare Part D plans can add Wegovy to their formularies now that it has a medically-accepted indication that is not specifically excluded from Medicare coverage. Because Wegovy is a self-administered injectable drug, coverage will be provided under Part D, Medicare’s outpatient drug benefit offered by private stand-alone drug plans and Medicare Advantage plans, not Part B, which covers physician-administered drugs.

How many Medicare beneficiaries could be eligible for coverage of Wegovy for its new use?

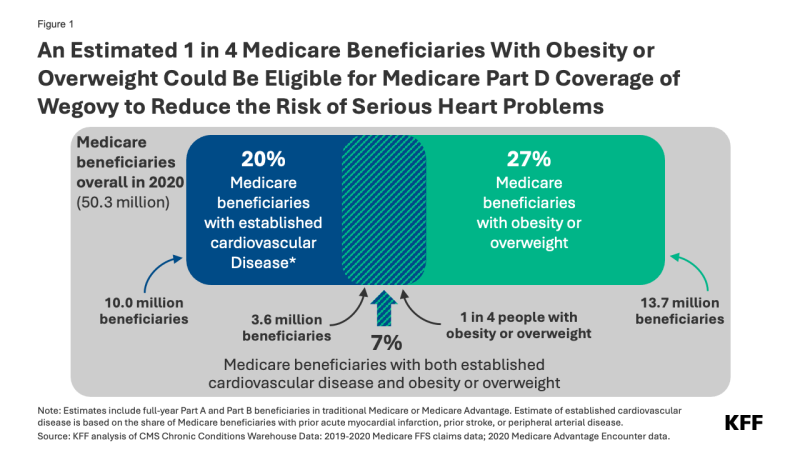

The new use of Wegovy is targeted to people with established cardiovascular disease – meaning a prior heart attack, prior stroke, or peripheral arterial disease – and either obesity or overweight. Based on KFF analysis of Medicare data from 2020, an estimated 7% of Medicare beneficiaries, or 3.6 million overall, had established cardiovascular disease and obesity or overweight in 2020, and so could be eligible for Medicare coverage of Wegovy for its new indication (Figure 1) (see Methods for details). This number may well be higher based on more current data than were available for this analysis. These 3.6 million beneficiaries represent just over a quarter (26%) of the 13.7 million Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed as being overweight or obese in 2020. This means that the FDA’s approval of the new use for Wegovy potentially opens up access to this drug for 1 in 4 people on Medicare with obesity or overweight.

Of these 3.6 million beneficiaries, 1.9 million also had diabetes (other than Type 1) and may already have been eligible for Medicare coverage of GLP-1s as diabetes treatments prior to the FDA’s approval of the new use of Wegovy.

Not all people who are eligible based on the new indication are likely to take Wegovy, however. Some might be dissuaded by the potential side effects and adverse reactions. Out-of-pocket costs could also be a barrier. Based on the list price of $1,300 per month (not including rebates or other discounts negotiated by pharmacy benefit managers), Wegovy could be covered as a specialty tier drug, where Part D plans are allowed to charge coinsurance of 25% to 33%. Because coinsurance amounts are pegged to the list price, Medicare beneficiaries required to pay coinsurance could face monthly costs of $325 to $430 before they reach the new cap on annual out-of-pocket drug spending established by the Inflation Reduction Act – around $3,300 in 2024, based on brand drugs only, and $2,000 in 2025. But even paying $2,000 out of pocket would still be beyond the reach of many people with Medicare who live on modest incomes. Ultimately, how much beneficiaries pay out of pocket will depend on Part D plan coverage and formulary tier placement of Wegovy.

Further, some people may have difficulty accessing Wegovy if Part D plans apply prior authorization and step therapy tools to manage costs and ensure appropriate use. These factors could have a dampening effect on use by Medicare beneficiaries, even among the target population.

When will Medicare Part D plans begin covering Wegovy?

Some Part D plans have already announced that they will begin covering Wegovy this year, although it is not yet clear how widespread coverage will be in 2024. While Medicare drug plans can add new drugs to their formularies during the year to reflect new approvals and expanded indications, plans are not required to cover every new drug that comes to market. Part D plans are required to cover at least two drugs in each category or class and all or substantially all drugs in six protected classes. However, facing a relatively high price and potentially large patient population for Wegovy, many Part D plans might be reluctant to expand coverage now, since they can’t adjust their premiums mid-year to account for higher costs associated with use of this drug. So, broader coverage in 2025 could be more likely.

How might expanded coverage of Wegovy affect Medicare spending?

The impact on Medicare spending associated with expanded coverage of Wegovy will depend in part on how many Part D plans add coverage for it and the extent to which plans apply restrictions on use like prior authorization; how many people who qualify to take the drug use it; and negotiated prices paid by plans. For example, if plans receive a 50% rebate on the list price of $1,300 per month (or $15,600 per year), that could mean annual net costs per person around $7,800. If 10% of the target population (an estimated 360,000 people) uses Wegovy for a full year, that would amount to additional net Medicare Part D spending of $2.8 billion for one year for this one drug alone.

It’s possible that Medicare could select semaglutide for drug price negotiation as early as 2025, based on the earliest FDA approval of Ozempic in late 2017. For small-molecule drugs like semaglutide, at least seven years must have passed from its FDA approval date to be eligible for selection, and for drugs with multiple FDA approvals, CMS will use the earliest approval date to make this determination. If semaglutide is selected for negotiation next year, a negotiated price would be available beginning in 2027. This could help to lower Medicare and out-of-pocket spending on semaglutide products, including Wegovy as well as Ozempic and Rybelsus, the oral formulation approved for type 2 diabetes. As of 2022, gross Medicare spending on Ozempic alone placed it sixth among the 10 top-selling drugs in Medicare Part D, with annual gross spending of $4.6 billion, based on KFF analysis. This estimate does not include rebates, which Medicare’s actuaries estimated to be 31.5% overall in 2022 but could be as high as 69% for Ozempic, according to one estimate.

What does this mean for Medicare coverage of anti-obesity drugs?

For now, use of GLP-1s specifically for obesity continues to be excluded from Medicare coverage by law. But the FDA’s decision signals a turning point for broader Medicare coverage of GLP-1s since Wegovy can now be used to reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke by people with cardiovascular disease and obesity or overweight, and not only as an anti-obesity drug. And more pathways to Medicare coverage could open up if these drugs gain FDA approval for other uses. For example, Eli Lilly has just reported clinical trial results showing the benefits of its GLP-1, Zepbound (tirzepatide), in reducing the occurrence of sleep apnea events among people with obesity or overweight. Lilly reportedly plans to seek FDA approval for this use and if approved, the drug would be the first pharmaceutical treatment on the market for sleep apnea.

If more Medicare beneficiaries with obesity or overweight gain access to GLP-1s based on other approved uses for these medications, that could reduce the cost of proposed legislation to lift the statutory prohibition on Medicare coverage of anti-obesity drugs. This is because the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), Congress’s official scorekeeper for proposed legislation, would incorporate the cost of coverage for these other uses into its baseline estimates for Medicare spending, which means that the incremental cost of changing the law to allow Medicare coverage for anti-obesity drugs would be lower than it would be without FDA’s approval of these drugs for other uses. Ultimately how widely Medicare Part D coverage of GLP-1s expands could have far-reaching effects on people with obesity and on Medicare spending.

Methods |

| The estimate of Medicare beneficiaries who could be eligible for Medicare coverage of Wegovy for cardiovascular disease is based on individual-level claims and encounter data for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage from the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW).

For beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, coding of individual-level fee-for-service (FFS) claims data matched the following chronic condition flags in the 2020 Medicare Beneficiary Summary File 30 CCW Chronic Conditions and Other Chronic or Potentially Disabling Conditions segments: AMI_EVER, STROKE_TIA_EVER, and OBESITY. In addition to obesity, beneficiaries were coded with overweight if the following ICD-10 codes were identified in the claims with the same requirements as the CCW OBESITY flag: E66.3, Z68.25, Z68.26, Z68.27, Z68.28. Z68.29. To identify beneficiaries with peripheral arterial disease (PAD), we used ICD-9 diagnosis codes for PAD identified by either Hirsh et al (August 2008) or Jaff et al (July 2010) in their analyses of peripheral arterial disease among Medicare beneficiaries; these studies are two of three references cited by CCW in the Other Chronic Conditions Algorithms Reference List for peripheral vascular disease. We used the ICD10Data website to convert the ICD-9 codes used in the Hirsch and Jaff studies to corresponding ICD-10 codes for our analysis based on the 2020 data (ICD-9 codes were replaced by ICD-10 codes in 2015). Beneficiaries who were coded with obesity or overweight and either a prior heart attack (AMI_EVER), prior stroke (STROKE_TIA_EVER), or peripheral arterial disease were coded as being eligible for the new use of Wegovy. Among this group, beneficiaries who were flagged as having diabetes (not including Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus) based on ICD-10 codes and using the same requirements as the CCW DIABETES flag, were identified as being eligible for GLP-1s approved for use as diabetes treatments. For Medicare Advantage enrollees, the ICD-10 codes for the CCW-developed algorithms for AMI, stroke, obesity, and diabetes (not including Type 1), plus ICD-10 codes specified above for overweight and peripheral arterial disease, were used to identify whether enrollees were eligible for the new use of Wegovy, based on 2020 encounter data and utilizing a within-year lookback period for all conditions (rather than ever, or in some cases a 2-year lookback that is used for traditional Medicare enrollees). Earlier years of data to enable a longer lookback period were not available for this analysis. Among the factors contributing to imprecision in the overall estimate:

It is not possible to measure the degree of uncertainty associated with these different factors. |