Out-of-Pocket Charges for Rape Kits and Services for Sexual Assault Survivors

This brief was updated on November 1, 2022.

| Box 1: Key Takeaways |

|

Introduction

Sexual violence impacts every community and affects people of all genders, sexual orientations, and ages, and often has lasting impacts on health and well-being. Sexual violence has been classified as a serious public health issue by the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In the US, more than 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men experience sexual violence in their lifetimes. The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) provides federal funding and guidance for programs to serve victims of sexual violence in the US. Despite the availability of federal and state funding and programs designed to support victims of sexual violence, many women face sizable out-of-pocket expenses for services they receive from a health care provider after a sexual assault.1 This brief examines the policies that impact coverage of health care services for survivors of sexual assault and identifies gaps in those programs and coverage for their care, particularly for women with private health insurance.

Overview of Federal and State Programs to Support Victims of Sexual Violence

The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) is the major federal legislation that provides funding and guidance for programs that aid victims of sexual violence. VAWA’s scope is broad, covering domestic violence, sexual harassment, stalking, and sexual assault. VAWA provides grants to states, local governments, and other organizations to establish their own violence-related programs and protocols. While the focus of public policies on sexual assault tends to be prosecution of perpetrators and the collection of evidence, provisions in VAWA also address health care coverage and costs.

- Violence Against Women Act (VAWA): First passed in 1994, VAWA authorizes federal funds to be used for services to aide individuals who are victims of sexual violence. VAWA requires states or another entity to provide no-cost rape kits and enforces and funds this requirement.

- Services, Training, Officers, Prosecutors (STOP) grants in each state. These grants are VAWA formula grants which support state and territory efforts to develop and strengthen law enforcement and prosecution strategies to address violence against women and improve victim services, such as paying for rape kits (or Medical Forensic Exams). According to federal law, in order to qualify for these grants states must “incur the full out-of-pocket cost of forensic medical exams” by providing or arranging for MFEs free of charge to victims of assault.

- Crime Victim’s Compensation Funds (CVCs): These state-level funds are established to reimburse victims for expenses related to crimes, which can include out-of-pocket expenses related to evidence collection and treatment. However, CVCs are typically the payer of last resort, and in most states, to be able to access the funds, the victim must report the crime to law enforcement within 72 hours of occurrence. These policies limit the availability of these funds to many victims of sexual violence.

What is a Rape Kit? It depends on where you live and where you go

Medical Forensic Exams (MFEs), Physical Evidence and Recovery Kits (PERKs), and Sexual Assault Forensic Exams (SAFEs) are all colloquially known as “rape kits.” In this brief, we use the terms MFE and rape kit interchangeably.

MFEs are used to collect evidence related to the sexual assault. The Office of Violence Against Women specifies that at a minimum, the standard medical forensic exam should include:

- gathering information from the patient for the forensic medical history

- head-to-toe examination of the patient

- documentation of biological and physical findings

- collection of evidence from the patient

- use of the exam space, such as an emergency room

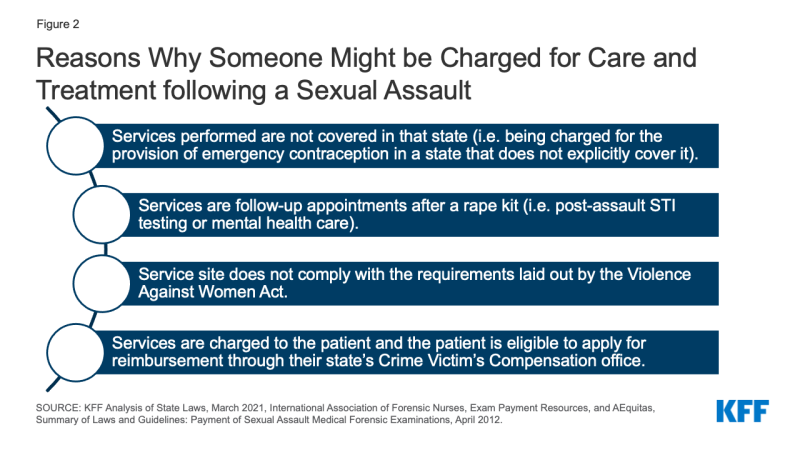

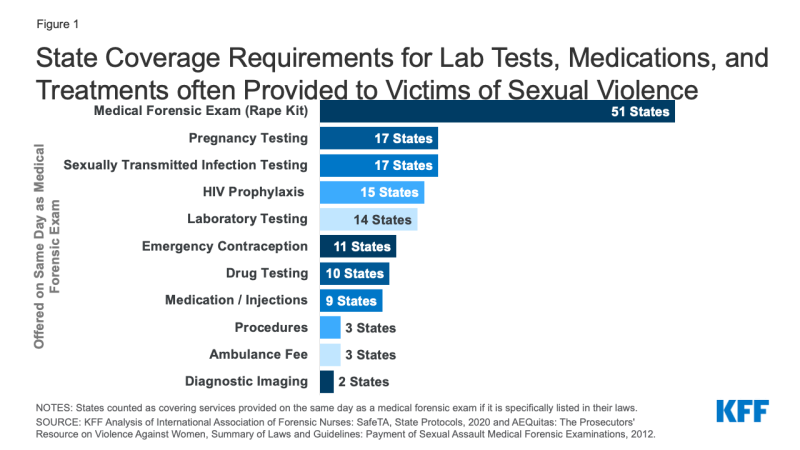

Beyond the minimum forensic exam, the Office of Violence Against Women states that “the inclusion of additional procedures (e.g., testing for sexually transmitted diseases) may be determined by the state in accordance with its current laws, policies, and practices.” Within these broad federal guidelines, states can define what is included in a rape kit which results in variation across the country. Although states are required to ensure that rape kits are provided at no-cost to survivors in order to qualify for STOP grants, there are often gaps in coverage for health care services that are outside of the MFE, like sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing, emergency contraception, or services for injuries incurred during sexual assault (such as stitches). Coverage policies for these services vary by state and are not necessarily guaranteed to be provided without cost-sharing.

The scope of coverage required by states is particularly unclear when it comes to lab testing, drug testing, pregnancy testing, and STI testing. For example, although MFEs typically include urinalysis, some states choose to specify that they cover these services as part of the kit, but many others do not. Because the services included in a rape kit are not explicitly defined in statute or by federal regulation, it is unclear whether states consider these services a part of the forensic exam (which they are required to cover in full per VAWA) or if they mandate them through separate state laws.

Furthermore, 17 states cap how much the state will spend on services per victim. For example, Georgia, Nevada, and Pennsylvania all limit spending to $1,000 per victim. Some states cap costs for the MFE, some states cap the costs paid to the provider but make clear that the patient will not have to pick up the extra costs, and some states specify ceilings for other services, such as medication or laboratory testing. Medical costs outside of the MFE may expose survivors to cost sharing following sexual assault in any state as VAWA does not explicitly mandate coverage for these services. Variation in state requirements contributes to differences in out-of-pocket costs between states.

Figure 1: State Coverage Requirements for Lab Tests, Medications, and Treatments often Provided to Victims of Sexual Violence

Access to Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners & Guaranteed No-Cost Rape Kits Varies by State and Exam Site

Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs) or Sexual Assault Forensic Examiners (SAFEs), which are used interchangeably in this paper, are clinicians who are specially trained in provision of rape kits. Forensic exam nurses often get certified as SANEs after some time of providing rape kits — during this time, as they have already gone through the training, they would still be included under the VAWA coverage requirements. VAWA’s no-cost coverage only applies to rape exams that states confirm meet the criteria outlined in VAWA, effectively exams that are often conducted by SANEs. However, SANEs and other specially trained examiners are not available in every hospital and it is difficult to know where to find a hospital that staffs one of these examiners. The only national database of SANE nurse locations was created in December of 2020 and has identified between 800 and 900 SANE programs in the U.S., whereas there are more than 6,000 hospitals nationally. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that access to SANE options and transportation varied across states. For example, the GAO found that survivors in some rural areas would need to travel two hours to find a hospital staffed by a SANE.

While some states, like Colorado and Massachusetts, publicly post a list of SANE locations, most states do not. As it stands, in order to find a trained examiner most survivors would need to call their local police department or a sexual assault service provider, like a hotline or local crisis center, or obtain access to the national database mentioned above. In some cases, the examiner may travel to the location of the patient to conduct the exam — in this case, it is the responsibility of the billing department to recognize the exam as covered, even if the location does not usually provide rape kits.

Although VAWA is widely believed to guarantee the provision of rape kits without cost-sharing for all, there are many gaps which may leave a survivor subject to out-of-pocket costs. These include a limited availability of rape kits, lack of clarity on coverage policies for non-SANE providers offering rape kits, as well as varying definitions of what services are included in rape kits between states, and unclear processes if a hospital or an insurer charges out of pocket costs (Figure 2).

Out-of-Pocket Costs for Rape Kit Services Under Private Insurance

According to a Department of Justice guide on STOP grant funding, states can require or ask victims to submit charges for exams to their personal insurance providers, but they must ensure that victims are not billed any costs, such as co-payments or deductibles, for the services that constitute the MFE. We analyzed a sample of private insurance medical claims from the 2016 to 2018 IBM Health Analytics MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, which contains claims information provided by large employer plans to examine out of pocket spending on typical rape kit services delivered in an outpatient hospital or emergency room setting. For more information see the Methods section.

Our analysis included identified episodes in which an adult women received a sexual violence diagnosis and either a STI test or exam procedure code typical of a rape kit (such as tissue examination or salvia swab), at an outpatient clinic, emergency room or urgent care clinic.

Eighty-three percent of women presenting under these circumstances and receiving an initial sexual violence diagnosis incurred out-of-pocket costs. On average, women facing out-of-pocket expenses in one of these cases faced $466 in cost-sharing, with half of women spending more than $226 dollars for all outpatient services.

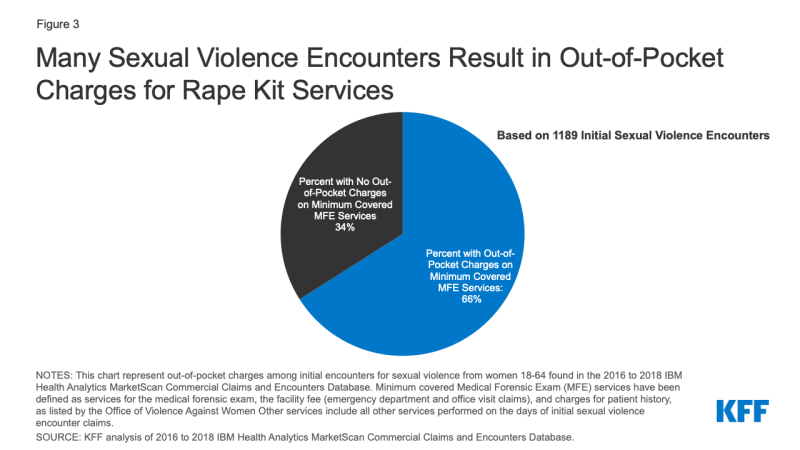

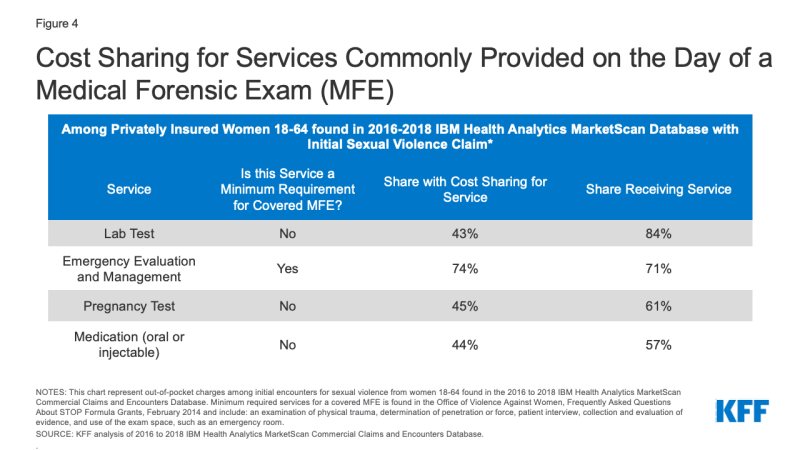

We then classified the different procedures that were billed as part of these encounters and identified a set of procedures that are often included as part of an MFEs: evaluation and management services or observation, patient history, swabs for DNA testing, and examinations of skin, hair, and nails. Two-thirds (66%) of survivors in this sample were charged out of pocket for at least one of these services (Figure 3). For example, among survivors who had a claim for emergency evaluation and management, roughly three quarters (74%) incurred out-of-pocket costs for these services. Among women facing cost-sharing for services often included in the MFE (an emergency room evaluation and management charge, an exam, patient history, pregnancy or STI test), victims with cost-sharing spent an average of $347 dollars, with half of women spending more than $200.

Many survivors also incurred cost sharing for a variety of services outside of the minimum covered services. While these services are not necessarily subject to the VAWA requirement for no-cost coverage of evidence collection, they are important components of care after a sexual assault for many survivors. For example, the majority of survivors had lab tests, pregnancy tests, and oral or injected medications such as antibiotics (Figure 4). Nearly half of all patients were charged out-of-pocket costs for these services. Other notable services, which were less frequently provided to survivors, also incurred out of pocket charges. This includes half (52%) of encounters that used an ambulance and almost half (47%) of those who had drug tests (data not shown). This analysis is consistent with previous research which also found that many patients were charged cost-sharing on days that they received rape kits.

These data illustrate that many survivors of sexual violence are faced with charges for health services typically considered standard care after sexual violence but not necessarily directly relevant to obtaining evidence for law enforcement.

For uninsured survivors, the costs for the MFE would go directly to the state agency paying for the evidence collection, but survivors could still be charged for services that are outside of the MFE. Out-of-pocket charges for these services could, in theory, be submitted for reimbursement through the survivor’s state Crime Victim’s Compensation (CVC) office.

Looking Forward

Sexual violence survivors often face an array of short- and long-term health needs. Provisions in the VAWA were intended to eliminate cost barriers for victims of sexual assault to obtain forensic exams following an assault. This analysis on the immediate health charges experienced by people following an incident of sexual violence finds that in a large sample of medical claims among adult women who are insured and who are provided with a rape kit following a sexual assault, most faced out-of-pocket costs for this care. While provisions in VAWA were intended to prevent out-of-pocket charges for this care, many survivors are still faced with charges.

Victims of sexual assault in all states should not have to pay any out of pocket costs for MFE services. However, our analysis finds that some women are being charged for these services. Whether they are insured or uninsured, many survivors would likely not have or be able to get the information they need to navigate this complex system and obtain funds to cover their out-of-pocket medical and health costs following a sexual assault. They would also have to know that their MFE could be charged to their insurance first, that coverage of costs outside of evidence collection depends on their state’s policies, and that their state’s CVC might be required to cover their remaining costs.

Existing gaps in VAWA can result in survivors facing cost-sharing or barriers to access when victims seek services. These include the overall lack of SANEs and other trained providers in many hospitals, variation between states in what services they require to be covered in a rape kit, and variation in rules and processes for accessing CVCs.

The newly reauthorized VAWA, recently signed by President Biden, the original sponsor of VAWA in 1993, will likely address some of these gaps. For example, the law supports the creation of the first government-sanctioned database that would identify where SANEs are located to increase the likelihood that a victim of sexual violence obtains an exam and receives care that protects them from out-of-pocket charges. However, the new law will not necessarily prevent out-of-pocket charges for all health services needed following an assault.

Some have proposed other options to address these gaps outside of the VAWA legislative vehicle. The Survivor’s Access to Supportive Care Act (SASCA), reintroduced to Congress in 2021, aims to increase access to and availability of SANEs and would require the Office of the Inspector General to issue a report concerning hospital compliance about access to and reimbursements for MFEs.

Despite the protections and funding that VAWA offers to support victims of sexual violence, some people continue to incur out-of-pocket spending after a sexual assault, presenting another barrier to care for those who have just experienced trauma.

Appendix 1: State Requirements for Coverage of Services in Medical Forensic Exams

Appendix 2: Methods for analysis of out-of-pocket costs in claims from IBM Marketscan database

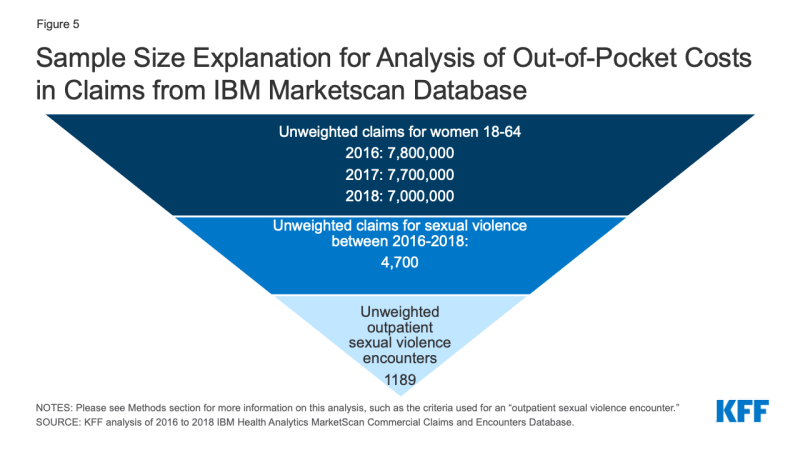

We analyzed a sample of medical claims obtained from the 2016 to 2018 IBM Health Analytics MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, which contains claims information provided by large employer plans. We only included claims for women between the ages of 18 and 64.

We further limited this analysis to women with claims for sexual violence (Figure 5). Sexual violence claims were defined as services in which an ICD-10 diagnosis code of T7421XA (Adult sexual abuse, confirmed, initial encounter), T7621XA (Adult sexual abuse, suspected, initial encounter) or Z0441 (Encounter for examination and observation following alleged adult rape) was assigned to the record. This method does not include services rendered to women who received a diagnosis of sexual exploitation, or received services to treat sexual violence after the initial encounter or in which another diagnosis was used on the claim. In total, over 4,700 unweighted enrollees had at least one claim of sexual violence over the three-year period.

| Sexual Violence ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes | |

| ICD-10 Diagnosis | Description |

| Z0441 | Encounter for examination and observation following alleged adult rape |

| TZ421XA | Adult sexual abuse, confirmed, initial encounter |

| T7621XA | Adult sexual abuse, suspected, initial encounter |

Of the 4,700 unweighted enrollees that had at least one claim of sexual violence over the three-year period, these claims were further limited to those submitted for outpatient care, meaning that inpatient services are not included or the cost of any retail prescription drugs they received after their visit. Claims were aggregated into an episode (‘outpatient days’), so that cost-sharing is considered spending that occurred on consecutive days in which a women has an sexual violence diagnosis and an STI or clinical exam.. We only considered cost-sharing that occurred during the initial encounter. Any cost-sharing on follow-up physician office visits were not included. We used a conservative denominator, including only days in which we expected a rape kit should have been administered: to do so we calculated days in which the survivor presented at an urgent care clinic or hospital (stdplac = 19, 22 or 23) and received both a sexual violence diagnosis and at least one STI test or exam. By doing so, we were attempting to exclude women who were receiving an initial sexual violence diagnosis weeks or years after the crime had been committed. We were unable to capture other locations where MFEs might be offered, like domestic violence safe houses or rape crisis centers.

In total there were 1189 unweighted sexual violence encounter outpatient days that met these criteria. Many of these outpatient days included claims with other diagnoses including depression screenings, treatments for physical violence or infection. In this analysis, we present cost-sharing for a limited set of services independent of these additional diagnoses. We looked at CPT codes related to pregnancy testing, STI testing, lab testing, drug testing, vaccines, medication (oral and injections), infusions, emergency department visits, patient history, office visits, diagnostic imaging, ambulance use, psychology use, contraception, pap smears, pregnancy care, procedures performed, physical therapy, and the MFE itself.

Figure 5: Sample Size Explanation for Analysis of Out-of-Pocket Costs in Claims from IBM Marketscan Database

Weights were applied to match counts in the Current Population Survey for enrollees at firms of a thousand or more workers by sex, age, and state. Weights were trimmed at eight times the interquartile range. On average 23% of women in large group plans are represented in the dataset.

This dataset does not include cases in which a person receives a rape kit but no claims are submitted to the insurer. Therefore, this data is not well suited for calculating prevalence of sexual violence, as spending is limited to women who received services, a diagnosis indicating sexual violence and the plan received the claim. This study attempts to discuss the cost-sharing faced by survivors presenting in a limited set of circumstances and not the financial burden of sexual violence overall. Cost-sharing includes the spending a woman faces from copays, coinsurances and deductibles.

The state policy tracking in shown in Appendix Table 1 was collected between June 2021 and December 2021. This data may change over time as fluctuations in state funds often impact what services states are able to cover.

Endnotes

The Department of Justice (DOJ) defines rape legally as the penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim. Nearly 1 in 5 women in the United States have experienced attempted or completed rape during their lifetimes. In this paper, rape and sexual assault are used interchangeably, although sexual assault is an umbrella term that also includes attempted rape, unwanted sexual touching, and forcing the victim to perform sexual acts. The reason these terms are used interchangeably in this paper is that rape kits and associated services may be needed even in cases outside of the scope of the DOJ definition of rape.